Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

370 Suboxone PDF

Încărcat de

Aprilihardini LaksmiTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

370 Suboxone PDF

Încărcat de

Aprilihardini LaksmiDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

PAIN Tutorial 370

Perioperative Management of

Opioid Use Disorder Patients on

Buprenorphine/Naloxone

Drs. Alan Tung1, Clinton Wong2, Nadia Fairbairn3

1

Anesthesia Resident, St. Paul’s Hospital, Canada

2

Clinical Professor, Division of Acute and Interventional Pain Management,

Department of Anesthesiology, St. Paul’s Hospital, Canada

3

Assistant Professor, British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, Division of AIDS,

Department of Medicine, St. Paul’s Hospital, Canada

Edited by

Dr. Amanda Baric

Anaesthetist, Department of Anaesthesia & Perioperative Medicine, Northern Health

Correspondence to atotw@wfsahq.org 9th Jan 2018

An online test is available for self-directed Continuous Medical Education (CME). A certificate will be

awarded upon passing the test. Please refer to the accreditation policy here. Take online quiz

KEY POINTS

• Illicit opiate use is a growing global problem, with 0.4% of the world using heroin or opium.

• Buprenorphine is used in the treatment of opioid use disorder, and has a high affinity but low intrinsic

activity for the µ-opioid receptor.

• The naloxone component is used to prevent parenteral diversion, and has no significant clinical effect when

taken sublingually or enterally.

• Continuing, reducing, or discontinuing buprenorphine/naloxone perioperatively requires careful

consideration of acute postoperative pain expectations, possible multimodal non-opioid analgesic options,

and psychosocial factors like relapse risk.

• A multidisciplinary team of surgeons, anesthesiologists, and addiction medicine specialists, is

recommended for perioperative management of opioid use disorder patients who are taking

buprenorphine/naloxone.

INTRODUCTION– OPIOID USE DISORDER

An estimated 2.1% of the United States population may have opioid use disorder (OUD), while a global estimate is

currently unknown (1). The diagnosis of OUD, per the Diagnostics Statistical Manual V, requires the patient to meet a

least two out of eleven criteria within twelve months, with severity of disease defined by the number of criteria fulfilled

(Table 1) (2). Multiple management options are available for OUD patients, with opioid agonist therapy – including

buprenorphine/naloxone, methadone, slow-release morphine, and injectable hydromorphone or diacetylmorphine

(heroin) – being the mainstay of treatment (3).

Buprenorphine/naloxone (Suboxone®, Zubsolv®, or Bunavail®), typically dosed between 8~24 mg of buprenorphine

daily for OUD, is an evidence-based therapy for OUD that is becoming increasingly common. A 2014 Cochrane Review

on buprenorphine’s effectiveness for OUD found that buprenorphine is more effective than placebo at all dose levels at

retaining OUD participants in treatment, while high doses (≥16 mg) help suppress illicit opioid use when detected by

urine drug screen(4). Compared to methadone, buprenorphine at medium (7~15 mg) and high doses were equivalent to

methadone’s medium (40~85 mg) and high (≥85 mg) doses respectively regarding treatment retention, self-reported

opioid use, and detection of illicit opioid use by urine drug screen.

Though similar in effectiveness to methadone, buprenorphine/naloxone (BUP/N) has been recommended as the first-line

treatment for OUD over methadone in some jurisdictions due to its relative safety profile (3). Buprenorphine is six-fold

safer than methadone for overdose risk due to a lower respiratory depression potential (3,5,6). Other advantages

Subscribe to ATOTW tutorials by visiting www.wfsahq.org/resources/anaesthesia-tutorial-of-the-week

th

ATOTW 370 – Perioperative management of opioid use disorder patients on buprenorphine/ naloxone (9 Jan 2018) Page 1 of 6

including more cost-effectiveness than methadone, and easier and faster titration of BUP/N over days, in contrast to

weeks for methadone, which may help decrease relapse rates. With the growing opioid and fentanyl overdose crises

affecting much of North America, efforts to expand access to OUD treatment are underway. Thus, anesthesiologists will

likely see more patients on buprenorphine/naloxone prior to elective or emergency surgery.

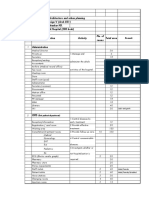

A problematic pattern of opioid use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, with at least two of the

following criteria within 12 months:

1. Opioids are taken in larger amounts or over longer periods of time than originally intended

2. Persistent desire or unsuccessful attempts to cut down or control opioid use

3. Significant amount of time spent on activities to obtain opioids, use opioids, and/or recover from its effects

4. Craving or strong urge to use opioids

5. Recurrent opioid use causing failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home

6. Continued opioid use despite persistent or recurrent social interpersonal problems that are worsened by

opioid use

7. Reduced or cancelled important social, recreational, or occupational activities

8. Using opioids in physically hazardous situations

9. Continued use of opioids despite the knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or

psychosocial problems that are worsened by opioid use

10. Tolerant to opioids

11. Experienced opioid withdrawal symptoms when taken off opioids

1

Table 1. Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) criteria, from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V . Severity

of OUD depends on the number of criteria fulfilled (2~3 = mild, 4~5 = moderate, ≥6 = severe).

BUPRENORPHINE AND NALOXONE – PHARMACOLOGY

Pharmacodynamics of buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a thebaine-based opioid with partial µ (mu)-receptor agonism (7). What makes buprenorphine unique

among opioids are its low intrinsic activity, high affinity, and slow dissociation for the µ-receptor (8). It is 30 times more

potent than morphine, but purportedly has as a ceiling µ-agonist effect somewhere between 8 and 16 mg.

Buprenorphine’s onset after sublingual administration is between 30 and 60 minutes, peaking at 100 minutes (9). Higher

doses result in prolonged duration: 4~12 hours for 4~8 mg, 24 hours for 8~12mg, and 2~3 days for ≥12 mg. Because

buprenorphine binds so strongly to the µ-receptor (Ki = 0.22, with a lower Ki meaning higher binding affinity), it can

displace other full opioid agonists with higher Ki (causing opioid withdrawal symptoms) or prevent them from binding to µ-

receptors (leading to ineffective analgesia) (Table 2).

Medication Ki (nM)

Codeine 734.2

Meperidine 450.1

Oxycodone 25.87

Methadone 3.378

Naloxone 1.518

Fentanyl 1.346

Morphine 1.168

Hydromorphone 0.3654

Buprenorphine 0.2157

Sufentanil 0.1380

Table 2. Ki of commonly used opioids and naloxone to µ-opioid receptors (2). Lower Ki signifies higher binding affinity.

Buprenorphine also has κ (kappa)-receptor antagonism, which may be involved in not only decreasing the risk of

respiratory depression related to opioid overdose, but also treating depression, stress, and addiction (9). However,

respiratory depression may still occur when used in conjunction with non-opioid sedatives like benzodiazepines (7).

Pharmacokinetics of buprenorphine

Buprenorphine/naloxone exists in sublingual tablet, sublingual film and buccal film, with increasing oral mucosal

absorption and bioavailability of buprenorphine respectively (30~52%) (7,10). Buprenorphine formulations without

naloxone (i.e. Butrans® transdermal patch, Subutex® sublingual tablet) are prescribed for other indications such as

chronic pain, but are generally not recommended for treating OUD due to diversion risk. Buprenorphine is highly

lipophilic, distributing rapidly to tissues but releasing slowly from tissues. It therefore exhibits a depot-like effect, with

higher doses resulting in longer duration. 96% of the drug binds to alpha- and beta-globulins. In the liver, buprenorphine

utilizes the CYP3A4 system to metabolize via N-dealkylation into norbuprenorphine, with modification by glucuronidation.

Norbuprenorphine binds to opioid receptors in vitro, but has not been studied clinically. Buprenorphine and its

metabolites are eliminated and excreted via urine (30%) and feces (69%). Renal or hepatic impairment do not appear to

significantly impact buprenorphine’s effects.

Subscribe to ATOTW tutorials by visiting www.wfsahq.org/resources/anaesthesia-tutorial-of-the-week

th

ATOTW 370 – Perioperative management of opioid use disorder patients on buprenorphine/ naloxone (9 Jan 2018) Page 2 of 6

Pharmacology of naloxone

Naloxone is a µ-receptor antagonist. Naloxone is combined with buprenorphine to cause opioid withdrawal when

buprenorphine is diverted parenterally for its euphoric effects. The 4:1 ratio with buprenorphine (i.e. buprenorphine:

naloxone 2mg:0.5mg) produces intense opioid withdrawal symptoms when injected, while the 8:1 ratio is less effective

(7). Given sublingually, naloxone only has 7~9% bioavailability, with no clinical significance (10). Naloxone undergoes

direct hepatic glucuronidation to naloxone-3-glucuronide for urinary excretion.

PERIOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF PATIENT ON BUPRENORPHINE/NALOXONE

Deciding on continuing, reducing, or discontinuing buprenorphine/naloxone

Buprenorphine prescribed for chronic pain are at sufficiently low doses (typically 150~900 mcg sublingually twice a day

or 5~20 mcg/hr transdermal patch) and the general recommendation is to continue buprenorphine perioperatively.

For OUD patients on BUP/N, there are currently no society or national guidelines nor trials to guide the perioperative

management of BUP/N; only Anderson et al have published their institution’s protocol in managing this issue (9). While

there are no evidence or trials, the decision to continue, reduce or discontinue BUP/N should be individualized to the

patient. The advantages, disadvantages and suggested indications for continuing, reducing, or discontinuing BUP/N are

described in Table 3.

Advantages Disadvantages Suggested Indications

Continuing • No change in prescription • Likely require higher doses of • None to mild post-

same dose of • Minimal relapse risk of OUD full opioid agonists to overcome operative pain

BUP/N • Utilizes BUP/N’s other effects buprenorphine’s high affinity for • Moderate pain with

(i.e. reduction in depression, µ-opioid receptors adequate non-opioid

stress, addiction) • Pain control may be analgesic adjuncts (i.e.

• No need to reinitiate BUP/N challenging if opioids are perineural blocks)

postoperatively required

Reducing the • More opioid receptors available • May experience some opioid • Moderate post-

dose of for full agonists to bind to, withdrawal symptoms during operative pain

BUP/N possibly increasing their tapering • Significant

analgesic efficacy postoperative pain

• Lower OUD relapse risk (vs. with adequate non-

discontinuation) opioid analgesic

• Utilizes BUP/N’s other effects adjuncts (i.e. epidural)

(i.e. reduction in depression, ± systemic opioids

stress, addiction)

• Easy re-titration of BUP/N

postoperatively

Discontinuing • Frees up opioid receptors to • Requires min. 1~5 days of • Significant post-

BUP/N allow other opioids to bind, taper operative pain

completely possibly increasing their full • May have severe opioid requiring significant

agonist efficacy withdrawal symptoms when amounts of systemic

tapered off, likely to require opioids

bridging using short-acting • Unable to use non-

opioids opioid analgesic

• Higher risk of relapse adjuncts to control

• Opioid tolerance will continue pain

to be an issue for opioid-based

pain management

• Challenging induction of BUP/N

(in setting of requiring narcotics

for pain management, with risk

of precipitating withdrawal

during induction), leading to

difficult discharge planning

Table 3. Advantages, disadvantages and suggested indications for continuing, reducing, or discontinuing

buprenorphine/naloxone perioperatively. (BUP/N = buprenorphine/naloxone, OUD = opioid use disorder)

What makes the perioperative management of BUP/N difficult to manage are the multiple considerations, including

BUP/N itself and the patient population. Though complex, perioperative management of BUP/N can be summarized into

two questions:

1. Can this patient’s pain be managed perioperatively while on buprenorphine/naloxone (at the same or

reduced dose)?

2. If buprenorphine/naloxone is discontinued, is there a well-defined plan to reinitiate buprenorphine/naloxone

postoperatively when appropriate to avoid relapse?

Subscribe to ATOTW tutorials by visiting www.wfsahq.org/resources/anaesthesia-tutorial-of-the-week

th

ATOTW 370 – Perioperative management of opioid use disorder patients on buprenorphine/ naloxone (9 Jan 2018) Page 3 of 6

The high doses of BUP/N used for OUD pose a significant concern regarding buprenorphine’s interference with opioid-

based analgesia. Buprenorphine’s high affinity and slow dissociation may prevent full opioid agonists with higher Ki from

binding to µ-receptors and relieving pain, but buprenorphine’s low intrinsic activity may not provide sufficient analgesia by

itself. Although unlikely to impact procedures with minimal postoperative pain, BUP/N may make pain control a challenge

for major surgeries associated with significant pain requiring opioids. For example, a patient on BUP/N who underwent

an emergency decompression and stabilization of C6-C7 fracture had higher anaesthetic and analgesic requirements,

than during a subsequent C5-T11 arthrodesis with posterior instrumentation after abstaining from BUP/N for 5 days (11).

Anderson et al recommend stopping BUP/N for surgeries known to have moderate to major postoperative pain to give

full agonist opioids better analgesic efficacy (9).

This issue is complicated by the patients themselves: OUD patients are usually opioid tolerant, anxious, and more

sensitive to pain, whether due to decreased pain threshold or hyperalgesia secondary to chronic opioid exposure (9,12).

To illustrate this, Chern et al found similar high analgesic requirements in a patient who was on BUP/N for her first

gynecological surgery versus off BUP/N prior to her second operation. MacIntyre et al found that patients on

buprenorphine who did not receive their dose on the morning of their surgery required more analgesics in the first 24

hours postoperatively (13). Consequently, discontinuing BUP/N does not necessarily simplify pain management

afterwards.

Managing postoperative pain while on BUP/N is still feasible. Kornfeld et al described seven such cases who underwent

major surgeries (i.e. right-sided colectomy, knee arthroplasties, bilateral mastectomies, etc.) and treated the pain

satisfactorily using perineural, neuraxial, and/or intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IV-PCA) (14). Advantages of

continuing BUP/N include avoiding the need and difficulty of re-initiating buprenorphine in a patient with acute pain, and

utilizing the potential κ-antagonism effects to reduce depression and stress reduction.

The relapse risk can also be minimized if BUP/N is continued perioperatively. Relapse rates after tapering off BUP/N

reaches above 90% (3). Discontinuing BUP/N several days pre-operatively will result in opioid withdrawal symptoms,

often necessitating a bridge of short-acting opioids during the taper. Furthermore, the surgery, the postoperative pain,

the fear of being judged, and the hospital setting are stressful and may trigger an OUD patient to leave against medical

advice to seek illicit opiates (15). BUP/N continuation may help mitigate relapse risk while under psychosocial stress and

therefore improve the patient’s long-term postsurgical success.

The current medical literature is focussed on continuing versus discontinuing BUP/N perioperatively (i.e. “To Stop or Not,

That is the Question”(9)), but a third option exists: decreasing BUP/N to a smaller dose. Interestingly, this choice is not

often mentioned in the literature, with one case report of a patient who developed severe refractory pain after a Clagett

window closure and achieved adequate comfort once her BUP/N dose was reduced to 8 mg (16). Decreasing the BUP/N

dose offers multiple advantages. A smaller dose of BUP/N will expose more µ-receptors for other opioids to bind to,

potentially improving analgesic efficacy as suggested by the case report. Moreover, having some BUP/N present permits

easy up-titration to pre-surgical doses, avoiding the risk of precipitating withdrawal. Patients may still experience opioid

withdrawal symptoms while on a lower BUP/N dose preoperatively, but it is unlikely to be of the same severity as that

from complete BUP/N discontinuation. Consequently, BUP/N reduction can be considered in lieu of discontinuation.

Lastly and most importantly, the value of a multidisciplinary team and a biopsychosocial approach to perioperative

BUP/N and pain management cannot be understated. Consulting addiction medicine specialists early can help with the

decision-making of continuing, reducing or discontinuing BUP/N preoperatively, and postoperatively during the

management of postoperative pain and OUD. Collaborating with surgeons, patients’ family physicians, and clinical

support staff like social workers and outreach nurses will assist with surgical planning to optimize postoperative

analgesia and minimize emotional distress.

Continuing or reducing buprenorphine/naloxone in elective surgery

The standard anaesthetic history and physical exam, a brief history of illicit drug use (including types of drugs and last

exposure), medical consequences (i.e. intravenous drug use: HIV, infective endocarditis, viral hepatitis, etc.), and

buprenorphine/naloxone dose and duration of treatment should be obtained. Rapport building is particularly important

with OUD patients. Avoiding words with judgemental connotations like “addict”, “habit” and “abuse”, and using objective

medical terminology – “illicit drug use”, and “opiate use disorder” – will help achieve this. As emphasized above, involving

relevant care providers (i.e. BUP/N prescriber) and addiction medicine specialists will assist with developing an

individualized perioperative plan and addressing the patient’s concerns. The preanesthetic interview should inform the

patient of realistic pain expectations, typical course of acute pain, and analgesic options, with reassurance that the pain

will be treated. Lastly, one should consider prescribing preoperative acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs (NSAIDs), and/or gabapentin when not contraindicated.

Intra-operatively, higher anaesthetic doses may be needed (11). For pain management, multimodal non-opioid

analgesics should be fully explored and administered if appropriate, including but not exclusively intravenous

medications, perineural and neuraxial nerve blocks (Table 4). If opioids are required, then a higher opioid consumption

should be expected than the typical non-OUD patient. Looking at binding affinities (Table 2), sufentanil and

hydromorphone are the ideal opioids to compete with buprenorphine for µ-receptor binding sites.

Subscribe to ATOTW tutorials by visiting www.wfsahq.org/resources/anaesthesia-tutorial-of-the-week

th

ATOTW 370 – Perioperative management of opioid use disorder patients on buprenorphine/ naloxone (9 Jan 2018) Page 4 of 6

NMDA antagonists (ketamine, magnesium)

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (ibuprofen, diclofenac, ketorolac)

Steroids (dexamethasone)

Alpha-2 agonists (clonidine, dexmedetomidine)

Local anesthetics (IV lidocaine, SC bupivacaine wound infiltration)

Perineural blocks (single shot, continuous)

Neuraxial block (spinal, epidural)

Table 4. Non-opioid analgesic options.

Post-surgery, acute pain service and/or addiction medicine specialists should be recruited for postoperative pain

management. One may consider splitting BUP/N into three to four times a day (q6~8 hours) dosing to maximize

buprenorphine’s analgesic properties (9,12). Non-opioid analgesics should be prescribed if not contraindicated: regular

acetaminophen and NSAIDs, intravenous lidocaine or ketamine infusion, and/or continuous perineural or epidural

analgesia. Should a short period of postoperative ventilation be needed for other reasons, then consider

dexmedetomidine for its sedative and analgesic effects.

If opioids are needed, then IV-PCA should be provided, with anticipation for higher doses than opioid-naïve patients.

Hydromorphone is preferred, and fentanyl is a suitable alternative given its high potency. Morphine at high doses,

despite its higher Ki value, has also been used successfully(14,17). If multimodal analgesia is unsuccessful, then

reducing or, as last resort, discontinuing the BUP/N dose should be considered(16). Once the acute pain phase is over,

the next steps are tapering off opioids and returning to the original dose of BUP/N (if reduced).

Many healthcare providers raise concerns about the high opioid consumption of OUD patients and “feeding their habit” or

addiction. Pain is a subjective perception. As stated above, not only are OUD patients opioid tolerant, but they also have

lower pain thresholds or hyperalgesia. When patients are in pain, opioids provide pain relief and minimal euphoria (12).

Our institution has taken the harm reduction approach: we would rather treat pain, than risk the patients leaving hospital

against medical advice to find relief using illicit opiates and relapsing, or developing complications from lacking care.

Measures to prevent diversion (i.e. opioids in oral solution, locked PCA pump) and frequent assessments for sedation

from excessive opioids should be routine care. With this in mind, higher acuity monitoring early postoperatively (i.e. 6~12

hours) may be necessary to manage high opioid doses.

Discontinuing buprenorphine/naloxone for elective surgery

In this situation, it is even more crucial to liaise with the patient’s BUP/N provider and the addiction medicine service to

safely taper off BUP/N preoperatively. The timing to stop BUP/N is directly related to the dose: 24 hours preoperatively if

on 0~4 mg of buprenorphine, 48 hours for 4~8 mg, 72 hours for 8~12 mg, and 3~5 days if ≥12 mg (9). Whether to bridge

with short-acting opioids during the taper should be discussed with the patient, provider and addiction medicine

specialist, the alternatives include morphine, hydromorphone, and methadone(9,12).

Intraoperative and postoperative considerations are similar to those on BUP/N, with the expectation that OUD patients

off BUP/N will still have high opioid requirements. The new complicating matter is restarting buprenorphine/naloxone.

Re-introducing BUP/N too early may precipitate withdrawal and worsen acute pain (leading to relapse and distrust of the

healthcare system), while discharging patients off BUP/N leaves them vulnerable to relapse and opioid overdose. Again,

working with addiction medicine and/or the BUP/N provider will help manage this issue. Generally, BUP/N could be

reinitiated once the pain is tolerable and requires minimal opioids. The patient should ideally be restarted on BUP/N

before discharge, which may mean prolonging hospital admission. If BUP/N cannot be initiated in-hospital and the

patient needs opioids, then safe opioid prescribing practices apply: limited number of oral narcotics prescribed to take

home, daily witnessed ingestion by a pharmacist or trusted relative, and close community follow-up, ultimately aiming to

restart BUP/N urgently before the patient relapses.

Buprenorphine/naloxone management in urgent or emergent surgery

Inquiring about the time and amount of the last BUP/N dose is crucial for assessing its impact on opioid withdrawal and

anaesthetic requirements. Possible sources of this information include the patient, the patient’s pharmacy, and the

patient’s computerized community medication list if available.

Management of BUP/N during urgent or emergency surgery is unclear. Anderson et al recommend stopping BUP/N and

providing IV-PCA postoperatively (9). However, at our institution, we suggest continuing BUP/N perioperatively.

Postoperative analgesic requirements will still be affected by buprenorphine due to its long duration of action. By the time

the buprenorphine is eliminated several days later, postoperative acute pain should be improving anyway, with the added

problem of re-introducing BUP/N later. The gradual elimination of buprenorphine becomes an unpredictable variable

affecting opioid titration. If pain control is unmanageable, then the BUP/N dose reduction should be considered.

Disposition to a monitored high acuity bed for opioid titration is suggested.

CONCLUSION

With the unique pharmacology of buprenorphine/naloxone and the complicated psychosocial, opioid-tolerant nature of

patients with opioid use disorder, having a multidisciplinary team approach comprising of surgeons, anaesthesiologists,

buprenorphine/naloxone providers and addiction medicine specialists can help achieve satisfactory pain control and a

smooth perioperative course.

Subscribe to ATOTW tutorials by visiting www.wfsahq.org/resources/anaesthesia-tutorial-of-the-week

th

ATOTW 370 – Perioperative management of opioid use disorder patients on buprenorphine/ naloxone (9 Jan 2018) Page 5 of 6

SUMMARY

• Illicit opiate use is a growing global problem and there are several described opioid agonist therapies.

• Buprenorphine is a partial µ-opioid agonist with long duration of action and a higher binding affinity

• When not contraindicated maximise non-opioid analgesic options described in Table 4.

This tutorial is estimated to take 1 hour to complete. Please record time spent and report this to your accrediting

body if you wish to claim CME points.

To take the online test accompanying this tutorial, please click here

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

1. Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Jung J, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Drug Use

Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. JAMA

psychiatry 2016;73:39-47.

2. Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th ed.

American Psychiatric Association; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.dsm16 (accessed

on August 22, 2017)

3. Provincial Opioid Use Disorder Treatment Guideline Committee. A Guideline for the Clinical Management of

Opioid Use Disorder. 2017. http://www.bccsu.ca/care-guidance-publications/ (accessed on July 15, 2017)

4. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M, Rp M, Breen C, et al. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or

methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane database Syst Rev 2014;2:CD002207.

5. Marteau D, McDonald R, Patel K. The relative risk of fatal poisoning by methadone or buprenorphine within the

wider population of England and Wales. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007629.

6. Bell JR, Butler B, Lawrance A, Batey R, Salmelainen P. Comparing overdose mortality associated with

methadone and buprenorphine treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009;104:73-7.

7. Suboxone monograph. 2017.

https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/UC

M227949.pdf (accessed on August 20, 2017)

8. Volpe DA, Tobin GAM, Mellon RD, Katki AG, Parker RJ, Colatsky T, et al. Uniform assessment and ranking of

opioid Mu receptor binding constants for selected opioid drugs. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol Elsevier Inc.;

2011;59:385-90.

9. T. Anderson T, Quaye A, Ward N, Wilens T, Hilliard P BC. To Stop or Not, That Is the Question.Acute Pain

Management for the Patient on Chronic Buprenorphine. Anesthesiology 2017;126:1180-6.

10. Chiang CN, Hawks RL. Pharmacokinetics of the combination tablet of buprenorphine and naloxone. Drug

Alcohol Depend 2003;70:39-47.

11. Khelemsky Y, Schauer J, Loo N. Effect of buprenorphine on total intravenous anesthetic requirements during

spine surgery. Pain Physician 2015;18:E261-4.

12. Alford DP, Compton P, Samet JH. Annals of Internal Medicine Perspective Acute Pain Management for Patients

Receiving Maintenance Methadone or Buprenorphine Therapy. Ann Intern Med 2006;149:698-707.

13. MacIntyre PE, Rusel RA, Usher KAN, Gaughwin M, Huxtable CA. Pain relief and opioid requirements in the first

24 hours after surgery in patients taking buprenorphine and methadone opioid substitution therapy. Anaesth

Intensive Care 2013;41:222-30.

14. Kornfeld H, Manfredi L. Effectiveness of full agonist opioids in patients stabilized on buprenorphine undergoing

major surgery: a case series. Am J Ther 2010;17:523-8. Available from:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19918165

15. Onukwugha E, Saunders E, Mullins CD, Pradel FG, Zuckerman M, Weir MR. Reasons for discharges against

medical advice: a qualitative study. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:420-4.

16. Huang A, Katznelson R, de Perrot M, Clarke H. Perioperative management of a patient undergoing Clagett

window closure stabilized on Suboxone(®) for chronic pain: a case report. Can J Anaesth 2014;61:826-31.

17. Mercadante S, Villari P, Ferrera P, Porzio G, Aielli F, Verna L, et al. Safety and Effectiveness of Intravenous

Morphine for Episodic Breakthrough Pain in Patients Receiving Transdermal Buprenorphine. J Pain Symptom

Manage 2006;32:175-9.

This work by WFSA is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivitives 4.0 International

License. To view this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Subscribe to ATOTW tutorials by visiting www.wfsahq.org/resources/anaesthesia-tutorial-of-the-week

th

ATOTW 370 – Perioperative management of opioid use disorder patients on buprenorphine/ naloxone (9 Jan 2018) Page 6 of 6

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Molecular Pathophysiology of StrokeDocument10 paginiMolecular Pathophysiology of StrokeKahubbi Fatimah Wa'aliyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kolbwhishaw80 PDFDocument13 paginiKolbwhishaw80 PDFAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patofisiologi StrkeDocument14 paginiPatofisiologi StrkeTeuku ILza Nanta SatiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nerve HistologyDocument4 paginiNerve HistologyAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Helpsheet DementiaQandA14 VascularCognitiveImpairment EnglishDocument4 paginiHelpsheet DementiaQandA14 VascularCognitiveImpairment EnglishAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal PDFDocument9 paginiJurnal PDFFerdy Arif FadhilahÎncă nu există evaluări

- VifDocument7 paginiVifAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- NerveDocument36 paginiNerveAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 581 PDFDocument64 pagini581 PDFkookiescreamÎncă nu există evaluări

- NerveeeDocument15 paginiNerveeeAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3-17 Nervous HandoutDocument12 pagini3-17 Nervous Handoutopthalmology 18Încă nu există evaluări

- Essential Neurology 4Th Ed PDFDocument290 paginiEssential Neurology 4Th Ed PDFPutu 'yayuk' Widyani WiradiraniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guyabano (Annona Muricata) : A Review of Its Traditional Uses Phytochemistry and PharmacologyDocument22 paginiGuyabano (Annona Muricata) : A Review of Its Traditional Uses Phytochemistry and PharmacologyellaudriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2060 PDFDocument20 pagini2060 PDFAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ss Mod3Document10 paginiSs Mod3tarun956519Încă nu există evaluări

- Antioksidan AntibakterialDocument8 paginiAntioksidan AntibakterialAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neurological Exam Lecture NotesDocument26 paginiNeurological Exam Lecture NotesNaveen KovalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Saraf KranialDocument41 paginiSaraf KranialIngwyPratiwiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medical UsesDocument3 paginiMedical UsesAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- How to Treat Fungal Foot Infections Like Tinea PedisDocument6 paginiHow to Treat Fungal Foot Infections Like Tinea PedisElfrida Fausthina LaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quercetin HypertensiveDocument8 paginiQuercetin HypertensiveAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Led Lamp CatalogDocument52 paginiLed Lamp CatalogAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pharmacological Evidences For The Extracts and Secondary Metabolites From Plants of The Genus HibiscusDocument12 paginiPharmacological Evidences For The Extracts and Secondary Metabolites From Plants of The Genus HibiscusAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3CD2F8211018Document4 pagini3CD2F8211018Nur Hayati IshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review Hibiscus PDFDocument9 paginiReview Hibiscus PDFAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology and Treatment JCGT 3 042Document9 paginiJournal of Clinical Gastroenterology and Treatment JCGT 3 042Loise MayasariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phytochemical Screening HibiscusDocument6 paginiPhytochemical Screening HibiscusAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Long-Term Outcomes of Titanium Ossiculoplasty in Chronic Otitis MediaDocument9 paginiLong-Term Outcomes of Titanium Ossiculoplasty in Chronic Otitis MediaAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review: Running Head: Nitric Oxide and Energy Balance in HypoxiaDocument70 paginiReview: Running Head: Nitric Oxide and Energy Balance in HypoxiaAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annona SquamosaDocument6 paginiAnnona SquamosaAprilihardini LaksmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- A Harmonious Smile: Biological CostsDocument12 paginiA Harmonious Smile: Biological Costsjsjs kaknsbsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guerbet Customer Success StoryDocument4 paginiGuerbet Customer Success StoryAshishkul10Încă nu există evaluări

- Anatomy and Physiology of The Reproductive SystemDocument31 paginiAnatomy and Physiology of The Reproductive SystemYUAN CAÑAS100% (1)

- Injeksi Mecobalamin Vas ScoreDocument5 paginiInjeksi Mecobalamin Vas ScoreHerdy ArshavinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Speaking Level Placement Test Business English PDFDocument2 paginiSpeaking Level Placement Test Business English PDFLee HarrisonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scoring BPSDDocument4 paginiScoring BPSDayu yuliantiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Skema Jawapan Gerak Gempur 1Document5 paginiSkema Jawapan Gerak Gempur 1Cikgu RoshailaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 4Document107 paginiModule 4roseannurakÎncă nu există evaluări

- ......... NCP CaseDocument34 pagini......... NCP Casevipnikally80295% (19)

- Name: Kashima Wright Candidate #: Centre #: Teacher: Ms. Morrison Territory: JamaicaDocument36 paginiName: Kashima Wright Candidate #: Centre #: Teacher: Ms. Morrison Territory: JamaicaKashima WrightÎncă nu există evaluări

- OCPD: Symptoms, Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument4 paginiOCPD: Symptoms, Diagnosis and TreatmentRana Muhammad Ahmad Khan ManjÎncă nu există evaluări

- Remark: (Out Patient Department)Document7 paginiRemark: (Out Patient Department)Tmiky GateÎncă nu există evaluări

- BSHF-101 E.MDocument8 paginiBSHF-101 E.MRajni KumariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plant NutrientsDocument10 paginiPlant NutrientsAdrian GligaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effectiveness of Occupational Goal Intervention For Clients With SchizophreniaDocument10 paginiEffectiveness of Occupational Goal Intervention For Clients With SchizophreniaIwanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Context & Interested Party AnalysisDocument6 paginiContext & Interested Party AnalysisPaula Angelica Tabia CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Menace of Immorality Among Nigerian YouthsDocument13 paginiThe Menace of Immorality Among Nigerian Youthsanuoluwapogbenga6Încă nu există evaluări

- Self Safety 2Document10 paginiSelf Safety 2Angela MacailaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management of Class I Type 3 Malocclusion Using Simple Removable AppliancesDocument5 paginiManagement of Class I Type 3 Malocclusion Using Simple Removable AppliancesMuthia DewiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment 4 Sampledetailed Spring23Document9 paginiAssignment 4 Sampledetailed Spring23sagems14Încă nu există evaluări

- Thalassemia: Submitted By: Jovan Pierre C. Ouano Submitted To: Mark Gil T. DacutanDocument8 paginiThalassemia: Submitted By: Jovan Pierre C. Ouano Submitted To: Mark Gil T. DacutanJvnpierre AberricanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Are You Dating Danger? An Interdisciplinary Approach To Evaluating The (In) Security of Android Dating Apps Author: Rushank ShettyDocument2 paginiAre You Dating Danger? An Interdisciplinary Approach To Evaluating The (In) Security of Android Dating Apps Author: Rushank ShettyAlexander RodriguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Pakistani Government Ministries and DivisionsDocument2 paginiList of Pakistani Government Ministries and DivisionsbasitaleeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Method Development and Validation For Estimation of Moxifloxacin HCL in Tablet Dosage Form by RP HPLC Method 2153 2435.1000109Document2 paginiMethod Development and Validation For Estimation of Moxifloxacin HCL in Tablet Dosage Form by RP HPLC Method 2153 2435.1000109David SanabriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A. Define Infertility: Objectives: Intended Learning Outcomes That TheDocument2 paginiA. Define Infertility: Objectives: Intended Learning Outcomes That TheJc Mae CuadrilleroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pregnancy Calendar For DogsDocument3 paginiPregnancy Calendar For DogsVina Esther FiguraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gurr2011-Probleme Psihologice Dupa Atac CerebralDocument9 paginiGurr2011-Probleme Psihologice Dupa Atac CerebralPaulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tuition Appeal Guidelines ExplainedDocument2 paginiTuition Appeal Guidelines ExplainedEnock DadzieÎncă nu există evaluări

- 798 3072 1 PBDocument12 pagini798 3072 1 PBMariana RitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practitioner Review of Treatments for AutismDocument18 paginiPractitioner Review of Treatments for AutismAlexandra AddaÎncă nu există evaluări