Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

A Concept Analysis of Conceptual Learning A Guide For Educators-Min

Încărcat de

Neo YapindoTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

A Concept Analysis of Conceptual Learning A Guide For Educators-Min

Încărcat de

Neo YapindoDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

A Concept Analysis of Conceptual Learning:

A Guide for Educators

Katherine A. Fletcher, PhD, RN, CNE; Vicki L. Hicks, MS, APRN;

Regina H. Johnson, MSN, RN; Delois Meyer Laverentz, MN, RN, CCRN-K;

Christina J. Phillips, DNP, APRN, FNP-C; Lynelle N.B. Pierce, MS, RN, CCNS, CCRN;

Deana L. Wilhoite, MSN, RN; and Jessica E. Gay, MSN, RN, RNC-MNN

C

ABSTRACT oncept-based curriculum design is gaining widespread

Background: Concept-based curricula, coupled with use in nursing education. This curriculum design is one

conceptual approach to teaching, fosters conceptual learn- response to the call for reform in nursing education to

ing. There is a need for clarity in the definition of conceptual address content overload and better prepare nurses for today’s

learning. Method: Walker and Avant’s method of concept complex health care environment (Institute of Medicine, 2010).

analysis was used. Results: Conceptual learning is a process A concept-based curriculum facilitates both deep understanding

in which learners organize concept-relevant knowledge, and the ability to apply knowledge to diverse situations through

skills, and attitudes to form logical cognitive connections re- the process of conceptual learning. However, no common defi-

sulting in assimilation, storage, retrieval, and transfer of con- nition of conceptual learning currently exists. Clarifying the

cepts to applicable situations, familiar and unfamiliar. Attri- definition will provide a referent for recognizing conceptual

butes identified were (a) recognizing patterns in information, learning. This article defines conceptual learning using Walker

(b) forming linkages with concepts, (c) acquiring deeper un- and Avant’s (2011) approach to concept analysis.

derstanding of concepts, (d) developing personal relevance,

and (e) applying concepts to other situations. Antecedents BACKGROUND

were (a) learner cognitive potential, (b) organized conceptual

framework, and (c) conceptual approach to teaching. Con- In a concept-based curriculum, content is structured around

sequences were (a) enhanced synthesis and analysis, (b) im- a defined set of concepts that form a unifying classification

proved problem solving, (c) ability to translate theory to prac- to frame the learning (Giddens, 2017). Concepts are defined

tice, (d) appreciation of linear/nonlinear ways of thinking, as organizing principles grouped in coherent ways (England,

and (e) enhanced concept construction. Conclusion: This Lockhart, & Sanders, 2015). Significant educational resources

analysis provides a referent for recognizing the occurrence of have been developed to promote the structure of concept-

conceptual learning and developing instruments to measure based curriculum and the conceptual approach to teaching.

its outcomes. [J Nurs Educ. 2019;58(1):7-15.] The learning outcomes of these structures and processes have

not been identified and are complicated by incongruent terms

in the literature. By defining conceptual learning and its as-

Dr. Fletcher is Clinical Professor, Ms. Hicks is Clinical Associate Profes- sociated characteristics, a basis will be provided to evaluate

sor, Ms. Johnson is Clinical Assistant Professor, Ms. Laverentz is Clinical learning outcomes.

Assistant Professor, Dr. Phillips is Clinical Assistant Professor, Ms. Pierce

is Clinical Assistant Professor, Ms. Wilhoite is Clinical Instructor, and Ms. Concept Analysis Method

Gay is Clinical Assistant Professor, University of Kansas, School of Nursing, Walker and Avant’s (2011) approach to concept analysis was

Kansas City, Kansas. used to examine and define the concept of conceptual learning.

The authors thank Sally Barhydt, Publication Consultant, University of With this approach, it is recommended to identify the concept to

Kansas, School of Nursing, for her assistance with editing. be studied, determine the purpose of the analysis, and through

The authors have disclosed no potential conflicts of interest, financial a deep and broad literature review describe the uses of the con-

or otherwise. cept, attributes, antecedents, and consequences. This process re-

Address correspondence to Katherine A. Fletcher, PhD, RN, CNE, Clini- lies heavily on the authors’ ability to recognize recurring themes

cal Professor, University of Kansas, School of Nursing, 8953 Hillview Drive, during an extensive literature search. To contribute to the con-

De Soto, KS 66018; e-mail: kfletche@kumc.edu. cept’s clarity, it is important to develop model, contrary, and

Received: February 5, 2018; Accepted: July 11, 2018 borderline or related cases to illustrate the concept (Giddens &

doi:10.3928/01484834-20190103-03 Brady, 2007). As the last step of concept analysis, Walker and

Journal of Nursing Education • Vol. 58, No. 1, 2019 7

sertations, and book chapters written in the English language. A

manual search of the reference lists of selected articles also was

conducted for additional sources. The search concluded when

no new records were found that revealed new information re-

lated to definition, attributes, antecedents, and consequences of

conceptual learning.

The initial search identified 103 articles (Figure 1). Af-

ter screening for duplication and applicability for conceptual

learning, 36 records were excluded. A full-text review of the

remaining 67 records was conducted, and an additional 34 re-

cords were excluded. A focus on concept-based teaching and/

or concept-based evaluation methods was reason for exclusion.

Thus, a total of 33 articles and book chapters were selected for

inclusion based on their ability to inform conceptual learning

and the effect on nursing education.

RESULTS

Concept Usage

During this stage of analysis, Walker and Avant (2011) rec-

ommend identifying as many uses of the concept as possible

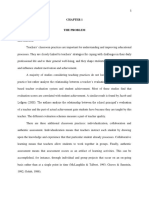

Figure 1. Flowchart showing the data selection process. to improve the richness and utility of the analysis outcomes.

The literature search revealed that conceptual learning is promi-

nent in educational journals and in the Boolean-valued function

Avant recommended investigating empirical referents for the found in machine learning associated with artificial intelligence

measurement of the concept. and library science.

After selecting a concept, the second step for researchers is In the literature from artificial intelligence and library sci-

to determine the intended purpose of their analysis (Walker & ence, conceptual learning was the term used to describe the

Avant, 2011). Keeping the outcome in mind while conducting logical functions to classify data (Milne, Witten, & Nichols,

the analysis will help determine the exact definition and defin- 2007). By using concepts, machines sort through data and re-

ing attributes of the concept. For the Kansas University School trieve information when requested. Terms such as and, or, and

of Nursing, the concept analysis of conceptual learning is part not are the primary operations that the machine uses to search

of a quality improvement project to measure the outcomes of for the data in library science. In artificial intelligence, machine

the learners’ educational process using a concept-based curricu- learning classifies a series of data based on certain given proper-

lum. An evidence-based analysis of conceptual learning will: (a) ties. The machine locates clusters within groups of data using

provide clarity in the definition and identification of attributes inductive reasoning, and these clusters represent concepts be-

of conceptual learning to facilitate the design of content within cause their properties are alike. These definitions of conceptual

a concept-based curriculum, (b) explore whether conceptual learning did not describe the type of learning that occurs within

learning provides the basis for understanding meaningful learn- students.

ing such as creative and critical thinking, and (c) provide a basis Many educators across disciplines and educational levels

to design methods to measure conceptual learning outcomes for (K-12 and graduate) have stated they are promoting conceptual

quality improvement and research purposes. learning. However, these educators have not defined conceptual

learning and often mix terms such as concept-based curricu-

DATA SOURCES lum, conceptual approach to teaching, and conceptual learning

without explaining the differences in meaning.

A series of literature searches were performed using the Although Giddens, Caputi, and Rodgers (2015), who are the

terms concept based, concept-based learning, concept-based champions in nursing for concept-based curriculum, discussed

teaching, concept-based curriculum, concept formation, and the science of learning in depth, they did not offer a definition of

constructivism. An initial search of the literature focused on conceptual learning. Only two definitions of conceptual learn-

nursing education literature in the Cumulative Index of Nurs- ing were found in the nursing literature. Timpson and Bendel-

ing and Allied Health (CINAHL®) database, which resulted Simso (2003) described conceptual learning as “the processes

in 48 articles from 1990 to 2017. Because the concept-based by which students learn how to better organize information in

curriculum had its origins in kindergarten through 12th grade logical mental structures, how to challenge ideas in light of new

(K-12) and postsecondary education, the literature search was data, and how to reorganize information and hypothesize new

expanded to all education literature with a search of the Edu- explanations” (p. 36). Arslan (2010) stated conceptual learning

cation Resources Information Center (ERIC™) database from “occurs as a result of a ‘combination’ of existing knowledge,

1970 to 2017. The expanded search identified an additional 51 and it enables individuals to understand and appropriate new

articles. Inclusion criteria were primary research studies, dis- knowledge” (p. 95).

8 Copyright © SLACK Incorporated

As the definitions of con-

ceptual learning were ex-

plored, it was evident that

these definitions did not de-

scribe conceptual learning in

a way that would differenti-

ate it from other forms of

learning. To this end, the au-

thors analyzed the literature

and developed the following

theoretical definition of con-

ceptual learning:

Conceptual learning is

a process in which learners

organize concept-relevant

knowledge, skills, and atti-

tudes to form logical cogni-

tive connections resulting in

assimilation, storage, retriev-

al, and transfer of concepts

to applicable situations, fa-

miliar and unfamiliar.

Defining Attributes

The next step in the con-

cept analysis process, ac-

cording to Walker and Avant

(2011), is to determine the

defining attributes of the

concept. Identifying these

defining attributes enables

one to recognize the concept

wherever it appears and to

differentiate it from other

concepts. Defining attributes

are those characteristics of a

concept that appear repeat-

edly in the literature and are

associated most frequently

with the concept (Walker &

Avant, 2011). As the litera-

ture on conceptual learning

was analyzed, certain themes Figure 2. Illustration depicting the conceptual learning analogy.

emerged as descriptions of

conceptual learning. All of

these descriptions were assimilated, and five major themes were ed concept in the same “file cabinet” (Figure 2). Recognizing

identified as the defining attributes of conceptual learning: patterns in the information allows the learner to assimilate and

• Recognizing patterns in information. sort information so it is understandable (Nielsen, 2016). The

• Forming linkages with a concept. best learners often seek patterns on their own, but many learn-

• Acquiring deeper understanding of a concept. ers need to have patterns pointed out to them more explicitly

• Discovering personal relevance and construction of value to (Leonard, Gerace, & Dufresne, 1999).

self. Forming Linkages With a Concept. The second attribute that

• Applying concepts to other situations. is evident in conceptual learning is the ability to form linkages.

Recognizing Patterns in Information. Conceptual learning is This means that the learner can connect the patterns of infor-

a process, and the first attribute noted is that the learner can rec- mation with preexisting conceptual knowledge. Using the fil-

ognize patterns occurring in information as it is received. Using ing cabinet analogy again, this second attribute would be the

an analogy of the brain as numerous “file cabinets,” patterning ability to store all similarly patterned information or facts in

is like placing information or facts that are related to a select- the same “file drawer” labeled with a theme connected to the

Journal of Nursing Education • Vol. 58, No. 1, 2019 9

concept. Memorization of facts that are not put into context is Applying Concepts to Other Situations. The fifth attribute of

a basic mental process (Erickson, 2012). It is the connection of conceptual learning is applying concepts to situations. Experts

the facts and knowledge to the larger picture that is important have the skill to retrieve applicable and appropriate knowledge

(Giddens et al., 2015). Ausubel, Novak, and Hanesian (1978) related to a presenting problem, which is referred to as con-

described how new knowledge acquired by learning is not lined ditionalized knowledge. Learners use their preexisting experi-

up or stacked on top of previously acquired knowledge but is ences or facts that are known to them to make connections and

integrated with previous knowledge to generate understanding form relationships while they synthesize new information and

of new interlocking concepts. Giddens et al. (2015) described discover further knowledge on their own (Sutherland, 1969).

this as extending the neuronal connections. Giddens et al. (2015) used the term neuroplasticity to describe

Leonard et al. (1999) compared the knowledge storage of the brain’s ability to reorganize and restructure itself though the

experts with that of novices and found that experts have a large formation of new neural connections because of learning expe-

storage of domain-specific knowledge that is richly intercon- riences.

nected. However, even novices have the ability to make linkages

at a beginning level and build on them. Rodehorst and Wilhelm Related Concepts

(2011) referred to these linkages as bridges between what the After the concept has been clearly defined and its attributes

learner currently knows and what the learner can learn. A ben- identified, it can be differentiated from similar concepts (Walk-

efit to making these connections is that it leads to deeper per- er & Avant, 2011). For the concept of conceptual learning, the

sonal inquiry (Erickson, 2012) and helps the learner retain the authors found a significant semantic problem. Many similar or

information (Rodehorst & Wilhelm, 2011). congruent terms are used throughout nursing education and the

Acquiring Deeper Understanding of a Concept. The third de- nursing literature, resulting in much confusion about what gen-

fining attribute of conceptual learning is acquiring deeper under- uinely constitutes conceptual learning. A consistent definition

standing of the concept. The learner in this process uses new and of conceptual learning with standardized attributes and termi-

preexisting knowledge to create a restructured understanding of nology is essential to identify and compare outcomes.

the concept (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001; Arslan, 2010; Guth- Commonly encountered terms in the literature include con-

rie, Van Meter, Hancock, Alao, Anderson, & McCann, 1998). Us- ceptual approach to teaching, concept-based curriculum, and

ing the file cabinet analogy, this attribute would be putting all the constructivism. The authors believe conceptual learning to be

new information or facts into already existing file folders with uniquely defined as a distinct phenomenon that should not be

similar information or making new file folders to hold newly dis- equated with similar terms or used interchangeably with terms

covered facts connected to the themes of the concept. that have different meanings and characteristics. Standardized

Deep understanding of any concept requires the learner to language can provide clear differentiation that is needed in this

use different examples of the same knowledge and interrelate emerging area of nursing education. The impetus for this article

the ideas through personal experience (Leonard et al., 1999). was the need to clearly define conceptual learning.

This clustering of the knowledge from examples to the concept Conceptual learning is the outcome that one would expect

helps to refine and sharpen the meaning of the concept (England from a learner who has been exposed to a curriculum that uses

et al., 2015; Leonard et al., 1999). Giddens and Brady (2007) a conceptual approach to teaching. Conceptual learning is the

discussed the importance of choosing exemplars carefully in a process that happens within the individual who interacts with

concept-based curriculum because they help the learner under- the concepts. A conceptual approach to teaching often is de-

stand the concept. The individual engaged in conceptual learn- scribed incorrectly in the literature as synonymous with con-

ing will be able to acknowledge the similarities and differences ceptual learning when they are actually two separate phenom-

within and between concepts (England et al., 2015) and develop ena. Conceptual approaches to teaching are strategies or actions

a deeper understanding through application of concepts in mul- used by the teacher to promote conceptual learning.

tiple contexts (Erickson, 2012). Constructivism is the process of acquiring knowledge in

Discovering Personal Relevance and Construction of Value which the knowledge is individually constructed and recon-

to Self. The fourth defining attribute of conceptual learning is structed by learners based on their interpretations from world

discovering a personal relevance to the concept and construct- experiences (Jonassen, 1999). This type of learning is centered

ing value to self. Conceptual learning must have a purpose that on a big picture idea that students can break down and then

is apparent to the learner. The learner’s perception of the value engage in parts of the whole. Through this experience, students

of what is being learned influences motivation. This motiva- will begin to understand the whole, see personal relevance, and

tion in turn influences what and how information is learned. change their worldview. Like conceptual learning, constructiv-

Transferring previous knowledge to a new learning situation is ism accepts personal relevance as part of the learning process

enhanced by creating a situation in which learners see the value, for every individual. In contrast, however, conceptual learning

the direct relationship to their area of study, and the implica- uniquely considers pattern information, forming linkages and

tions of why it is important. With this type of application, the applying concepts to familiar and unfamiliar situations as criti-

learner can see the benefit while learning (Giddens et al., 2015). cal components of learning.

Conceptual learning allows learners to use their own personal Examination of all the related terms is an essential part of the

relevance to make connections with the concept so they recon- concept analysis process to clearly differentiate the definition

struct a new personal reality of that concept and thus increase and defining attributes of the studied concept. Distinguishing

its value. these related concepts from conceptual learning helps to elimi-

10 Copyright © SLACK Incorporated

nate confusion and provide clarity in the phenomenon so that it made within her mind. Also empowering to the learner (Cassie)

can be measured. is the fact that application of knowledge can be made without

knowing all of the details of the situation (England et al., 2015).

Constructed Cases Higher order thinking (Getha-Eby, Beery, O’Brien, & Xu,

Another necessary step in concept analysis, according to 2015), as measured over time, increases correlationally as the

Walker and Avant (2011), is to construct cases to clearly dem- learner progresses along the continuum of conceptual learning.

onstrate the concept. The authors developed a model case, a re- Indeed, Getha-Eby et al. (2015) proposed that the learning out-

lated case, and a contrary case to illustrate the unique definition comes/consequences of conceptual learning may not be readily

and defining attributes of conceptual learning. apparent but will develop and strengthen over time.

Model Case. The following model case is a pure exemplar Related Case. A related case is one in which only some of

because it includes all of the defining attributes of conceptual the defining attributes are present (Walker & Avant, 2011). The

learning. idea is similar but distinguishable from the concept in question.

Cassie, a nursing student, learns about the concept of perfu- When discussing conceptual learning, it is important to distin-

sion during a classroom session. Her group examines an exem- guish it from other related ways of learning, such as construc-

plar case study of a patient with peripheral vascular disease. tivism. Studying related concepts ensures that instruction builds

They gather data from the case to identify the attributes of depth of understanding by attending to, and adding to, the lan-

perfusion and formulate a person-centered plan of care. Earlier, guage of each subject area (Erickson, 2012). The related case

Cassie studied the concept of clotting. She recognizes that per- is as follows:

fusion is an interrelated concept to clotting, but these concepts Sean, a nursing student, is in an acute care clinical setting

have different attributes. Cassie reflects that her grandmother today. He is assigned a patient diagnosed with thrombophlebi-

experiences pain in her legs, her toes become pale when walk- tis. At the preconference meeting, Sean stated, “My grandfather

ing short distances, and the pain stops once she stops walking. had a clot in his leg and developed a breathing problem, and he

This is not a clotting problem because the extremity would ap- had to be admitted to the hospital intensive care unit. He had to

pear swollen and the pain would be continuous. Cassie recog- be on blood thinning drugs for a long time after that. I know that

nizes that her grandmother probably has a perfusion problem I will probably have to keep this patient on bed rest and assess

and shares her grandmother’s signs and symptoms with the for shortness of breath because that could be a complication for

group when they talk about patent arterial blood vessels and this patient. I also had a patient with this problem last semester,

adequate blood and hemoglobin as some of the defining char- and I remember that he complained of aching pain in his leg, so

acteristics of perfusion. I need to assess for pain.” Sean recalled his classroom exemplar

In the clinical setting one week later, Cassie is assigned a and remembered that he might need to keep the leg elevated to

patient with Raynaud’s disease. She has never cared for a pa- decrease the swelling and pain.

tient with this diagnosis. In her assessment of the patient, she In this case, the learning theory of constructivism is like con-

notes that the left lower extremity is pale, cool to the touch, ceptual learning in that it is based on the notion that learning is

and pulseless. The patient reports pain in his left foot. Cassie experiential and cannot be divorced from previous experiences.

recalls what her small group discussed about perfusion and rec- The Business Dictionary (n.d.) describes constructivism as a

ognizes that Raynaud falls within the perfusion concept. Cassie teaching philosophy in which “each student creates his or her

recalls nursing interventions appropriate for this patient, which own ‘schemas’ or mental-models to make sense of the world,

include keeping the left lower extremity in a dependent posi- and accommodates the new knowledge (learns) by adjusting

tion, applying a warm blanket to the legs, assessing the circula- them.” As illustrated in this related case, the individual is seen

tion of the extremity frequently, and informing the primary care as responsible for constructing knowledge based on previous

provider of any changes. experiences and assimilation of new information, encompass-

In the case of conceptual learning, learners identify pat- ing the learner’s past and present (constructivism). Conceptual

terns in information using concepts as defined by specific at- learning takes the learning one step further, creating transfer of

tributes. Learners can practice with exemplars of the concept knowledge to future unknown situations and contributes to fu-

through case studies and other group classroom activities; in ture responses of the learner. Giddens, Wright, and Gray (2012)

doing so, learners have an opportunity to experience the con- stated that “development of conceptual thinking skills helps

cept in a personal way. In this case, Cassie can discern simi- learners recognize certain aspects of the presenting condition

larities and differences between concepts, revealing linkages and attain a general understanding of what to do” (p. 512). This

between concepts and existing knowledge. In experiencing the is different from Sean’s case in which he relies heavily on his

exemplars of a concept, she attaches personal relevance to the previous experiences rather than conceptual knowledge. When

information, ensuring retrieval of the information when needed. placed in a situation that he has never experienced before, Sean

As Cassie then applies this new connected, linked, relevant most likely will rely on past experiences and may have difficul-

knowledge to a clinical situation, a deep understanding of the ty differentiating the patient’s clinical problem and determining

concept is formed. When presented with an unfamiliar situa- appropriate actions.

tion, Cassie can anticipate or predict the attributes of this new Contrary Case. A contrary case is one in which none of the

exemplar because she recognizes similarities and differences defining attributes are present and is often the opposite of the

between known concepts. Retrieval is made easier because of phenomenon—conceptual learning—being described (Avant &

the deep understanding and personal relevance of the linkages Walker, 2011). A contrary case to conceptual learning is factual

Journal of Nursing Education • Vol. 58, No. 1, 2019 11

learning or memorization that focuses on facts or sequences al., 1999; Smith & Zeng, 2004). This type of outcome would

of events and memorization of specifics or operations (Arslan, be recognized as the learner being able to translate and make

2010). When the learner simply memorizes a fact and then tries cognitive connections from theory to practice and not simply

to recall the fact, it must be requested in the exact form it was memorizing facts (Deane & Asselin, 2015).

memorized to be recognized. If the examination item or practi-

cal situation is not exactly the same as the memorized statement, Antecedents and Consequences

the learner may have difficulty choosing the correct response The next step in concept analysis is identifying the anteced-

or action. The learner’s ability to recognize patterns within in- ents and consequences that occur around the concept (Walker

formation is not cultivated in the action of rote memorization. & Avant, 2011). Antecedents are the processes that precede the

In this type of learning, no personal meaning or relevance is concept, in this case that precede conceptual learning.

attached to the fact. No experience with the information has oc- Antecedents. The literature on conceptual learning was ana-

curred to link it to long-term and preexisting knowledge. Mem- lyzed through an iterative process, and three antecedents were

orization does not create deep understanding because context is found to be essential for conceptual learning to occur: learner

often absent. Because no meaning is attached to the information cognitive potential, an organized conceptual framework, and a

memorized, it only can be retrieved for a short period of time. conceptual approach to teaching.

Over the long term, information is lost. Information is not ap- Learner cognitive potential. The first antecedent, learner

plied to situations and therefore has no staying power; unrelated cognitive potential, begins forming at birth. This includes the

facts are quickly forgotten. The contrary case is as follows: learner’s intellect and experiences, previous learning, motiva-

Molly, a beginning nursing student, has performed well on tion, and mental operations and processes. The learner brings

section exams due to a practiced skill of memorizing impor- intellect and experiences to the conceptual learning environ-

tant facts taught in class. In the clinical setting today, she is ment. Johnson (1996) identified intellectual skills as “mental

assigned a patient who is experiencing peripheral arterial dis- operations that enable us to acquire new knowledge, apply that

ease. Molly recalls from a recent pathophysiology lecture and knowledge in both familiar and unique situations, and control

nursing foundations class that there are five Ps that indicate the the mental processing that is used to acquire and use knowl-

symptoms of peripheral arterial disease. When preparing for her edge” (p. 2). An individual learner’s motivation, intellect,

morning assessment, Molly tells the clinical instructor that she and prior life experiences will vary and influence the way the

will examine the patient’s pain, pallor, paresthesia, poikilother- learner views learning. To build on intellect and life experi-

my, and pulselessness. Several weeks later, Molly encounters ence, learners bring previous learning and existing knowledge

a patient with a peripheral vascular problem but when asked of concepts to the learning situation (Arslan, 2010; Leonard

about typical signs and symptoms of this disease, Molly is un- et al., 1999). All learners come with an existing mental struc-

able to recall any, stating, “I haven’t studied this condition be- ture that allows them to organize and pattern information

fore in class, so I don’t know the symptoms.” (Leonard et al., 1999). This existing mental structure of con-

Arslan (2010) stated, “Procedural learning (memorizing op- ceptual knowledge is the previously mentioned file cabinet.

erations) does not guarantee conceptual learning (understand- When learning occurs, the learner organizes new knowledge

ing and interpreting concepts), but conceptual learning supports in the brain into file drawers that match existing patterns. The

procedural learning” (p. 105). Therefore, when the conceptual learner can reorganize the file drawers or files at will as new

learner recognizes a learned concept in a new situation, that knowledge is discovered.

learner also can predict the correct procedural response required Organized conceptual framework. The second anteced-

in the new situation. ent, an organized conceptual framework with clearly defined

In this case, Molly recently memorized the information re- concepts, must be present. An organized framework provides

lated to this patient’s specific disease. Over time, Molly may structure that learners and faculty use to pattern their mental

well forget what to do, since she may not encounter another processes; this allows learners and faculty to have the same-

patient with this disease for some time. In addition, Molly has shared mental model in learning environments. Giddens and

learned how to respond only to this specific disease or diagno- Brady (2007) stated “the need for universal understanding and

sis and has memorized the response to this situation alone. The consistent use of concepts among faculty is critical for curric-

factual learning that has served Molly well in the past is not up ulum success” (p. 67). Giddens et al. (2012) noted “a process

to the task of managing this unknown situation. In the case of for the selection of concepts, competencies, and exemplars on

conceptual learning, Molly would have knowledge that could which to build courses and base content is needed” (p. 511). In

be applied more broadly to similar patient problems that include addition, clear definitions of concepts allow learners to iden-

similar concepts to those she has learned. tify a concept when encountered and recognize when it is not

Learners who learn conceptually develop the ability to think present. Gavalcante, Newton, and Newton (1997), in a study

like scientists rather than solely remembering information of 9- to 10-year-old children, found that students who had the

(Smith & Zeng, 2004). The learner uses multiple ways of know- greatest gains in conceptual understanding were those who

ing by using a set of concepts and their interrelationships to were provided clear mental structures of the concepts prior to

solve problems (cases) versus depending on rote memorization. the teaching.

Good clinical judgment would be recognized in the form of im- Conceptual teaching approach. The third antecedent is a

proved problem solving skills that would move the individual conceptual approach to teaching. Although an organized con-

from novice to expert as new knowledge is gained (Leonard et ceptual framework and clearly defined concepts are necessary

12 Copyright © SLACK Incorporated

to support conceptual learning, it also is essential to have a con- late theory into practice. Use of conceptual learning is intended

ceptual approach to teaching. This type of instruction typically to deepen learners’ thinking, pattern recognition, appreciation

involves the introduction of a concept, presentation of exemplars of practice outcomes and lifelong learning, and develop key

of the concept, and application of the concept (Giddens, 2008). skills related to clinical outcomes (Giddens et al., 2012; John-

Using exemplars of a concept allows cognitive connections to son, 1996; Nielsen et al., 2013). Learners with a well-organized

be formed and learning to be retained so that it becomes retriev- knowledge of concepts can apply theoretical knowledge faster

able and applicable to new situations (England et al., 2015). The using critical thinking in the practice arena (Bransford, Brown,

concept and its defining attributes help learners recognize the & Cocking, 1999). This deep understanding allows learners to

concept’s presence and absence using exemplars. A conceptual creatively apply the theoretical knowledge to relevant practice

approach to teaching also is characterized by instructional ac- situations.

tivities that are learner centered, actively engaging the learner Appreciation of linear and nonlinear ways of thinking.

and focusing on making cognitive connections from previous The fourth consequence of conceptual learning is the appreci-

to new knowledge and from theory to practice (Deane & As- ation of linear and nonlinear ways of thinking. On initial entry

selin, 2015). Even a well-designed concept-based curriculum into the learning process, the learner has years of prior ex-

would not be successful unless the faculty embrace conceptual periences that come with emotional attachment to an already

learning (Giddens & Brady, 2007). A key to the success of the formed worldview (Leonard et al., 1999). Conceptual learning

enhanced environment is a faculty committed to and actively requires the learner to become an active participant in sharing

practicing a conceptual approach to teaching. these lived experiences and perspectives that become a filter

Consequences. The consequences or outcomes are those for interpreting all learning experiences (Leonard et al., 1999).

events that emerge as a result of the occurrence of the concept As new concepts and constructs are introduced to a learner, it

(Walker & Avant, 2011). The literature addressing conceptual may be difficult for the learner to identify what features are

learning was examined, and five major outcomes or conse- most relevant based on his or her prior worldview. However,

quences of conceptual learning emerged: enhanced synthesis, as new knowledge is introduced, new patterns and ways of

reasoning, and analysis skills; improved problem-solving skills; knowing are created. The learner’s prior worldview begins to

ability to translate theory to practice; appreciation of linear and filter experiences through the new concepts, which affects all

nonlinear ways of thinking; and enhanced concept construction. interpretations of subsequent experiences and observations.

Enhanced synthesis, reasoning, and analysis skills. The The learner begins to build useful knowledge structures that

first consequence of conceptual learning is enhanced synthe- embrace both linear and nonlinear ways of thinking, which

sis, reasoning, and analysis skills (Giddens, 2013; Lasater & allows the learner to see how a concept manifests itself in a

Nielsen, 2009; Nielsen, Noone, Voss, & Matthews, 2013). With variety of different ways. Linear and nonlinear ways of think-

enhanced understanding of the concept, learners transfer the ing help the learner become an engaged and active participant

knowledge about the concept and make meaningful applica- in sharing various perspectives while simultaneously hearing

tions during problem solving activities. The mastery and ap- the cumulative perspectives of others, thus changing previous

plication, deep thinking, and transferable understanding enables learning patterns into restructured and reorganized constructs

learners to appreciate new knowledge that links theory to prac- that yield a more global and generalizable application (Bran-

tice (Arslan, 2010). As a result, learners are more satisfied as don & All, 2010).

they integrate knowledge more quickly and will gain command Enhanced concept construction. The fifth consequence

of more elements, features, and functions in a particular domain of conceptual learning is enhanced concept construction. An

(Guthrie et al., 1998). enhanced inductive, lifelong pattern of concept construction

Improved problem-solving skills. The second consequence is created through faster and deeper understanding of the

associated with conceptual learning is improved problem- concept, a continual transfer and connection of new knowl-

solving skills. In conceptual learning, those who have gained edge with previous knowledge, and improved higher order

a deeper understanding of the concepts tend to have sharper thinking (Fromer, 2013; Getha-Eby et al., 2015). According

thinking and reasoning skills and can identify commonali- to Erickson (2012), this type of learning “builds depth of un-

ties among exemplars and concepts. This deeper understand- derstanding by attending to, adding to the language” (p. 17)

ing allows learners to connect new knowledge with previously of the concepts over time. Learners take new factual knowl-

learned knowledge (Fromer, 2013) and to recognize patterns edge and integrate it with previous knowledge of the concept

and links beyond a diagnosis. The learner’s development of by creating a new depth of understanding that builds breadth

conceptual thinking skills helps with the recognition of certain and application of the concept, allowing new learning to

aspects of the presenting condition to attain a general under- be applied to new situations more quickly. This process of

standing of what to do (Giddens et al., 2012). The use of key higher order thinking contrasts with a lower level thinking in

concepts prevents an overreliance on memorization of facts as which learners who are taught a skill often fail to recognize

the end goal. The focus shifts from memorization, which is a that this new skill can be used later to solve similar problems

lower form of mental engagement, to deeper, personal inquiry (Johnson, 1996).

as learners consider connections between the facts and the key

concepts in reaching sound clinical judgment. Empirical Referents

Ability to translate theory to practice. The third conse- In the final step of concept analysis, Walker and Avant

quence of conceptual learning is the ability for learners to trans- (2011) recommended identifying the empirical referents (i.e.,

Journal of Nursing Education • Vol. 58, No. 1, 2019 13

plication to curricula. Nursing Education Perspectives, 31, 89-92.

examples or instruments) found in the literature that can be Bransford, J.D., Brown A.L., & Cocking, R.R. (Eds.). (1999). How people

used to describe or measure the concept. This is important learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: National

because it allows the researcher to observe and measure the Academies Press.

concept, as it exists in the world. The authors were unable Business Dictionary. (n.d.). Constructivism. Retrieved from http://www.

businessdictionary.com/definition/constructivism.html

to find any empirical referents in the literature for conceptual Deane, W.H., & Asselin, M. (2015). Transitioning to concept-based teach-

learning, exemplifying the need for further work. A future ap- ing: A discussion of strategies and the use of Bridges change model.

plication of this concept analysis would be to use this informa- Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 5(10), 52-59.

tion to construct and test instruments that would measure the England, S., Lockhart, L., & Sanders, E. (2015). A case for concept-based

concept. nursing education. Texas Nursing Voice, 9(3), 3-5.

Erickson, H.L. (2012). Concept-based teaching and learning. Retrieved from

http://www.ibmidatlantic.org/Concept_Based_Teaching_Learning.pdf

LIMITATIONS Fromer, R.F. (2013). A theory-driven integrative process/outcome evalua-

tion of a concept-based nursing curriculum (Unpublished doctoral dis-

The purpose of this concept analysis was to develop a com- sertation). Capella University, Minneapolis, MN.

Gavalcante, P.S., Newton, D.P., & Newton, L.D. (1997). The effect of vari-

mon definition of conceptual learning for faculty. A limitation ous kinds of lessons on conceptual understanding in science. Research

of this concept analysis is that it has been conducted by nurse in Science and Technological Education, 15, 185-193.

educators who practice within the framework of a concept- Getha-Eby, T.J., Beery, T., O’Brien, B., & Xu, Y. (2015). Student learning

based curriculum and who use teaching strategies that pro- outcomes in response to concept-based teaching. Journal of Nursing

mote conceptual learning. Because of their perspective, these Education, 54, 193-200. doi:10.3928/01484834-20150318-02

Giddens, J.F. (2008, October). Understanding concepts and the conceptual

authors have biases that may favor this form of teaching and approach: Infusing conceptual learning into the classroom [PowerPoint

learning. presentation]. University of Kansas School of Nursing, Kansas City.

Giddens, J.F. (2013). Concepts for nursing practice. St. Louis, MO:

CONCLUSION Elsevier-Mosby.

Giddens, J.F. (2017). Concepts for nursing practice (2nd ed.). St. Louis,

MO: Elsevier-Mosby.

This concept analysis provides a comprehensive overview Giddens, J.F., & Brady, D.P. (2007). Rescuing nursing education from con-

of conceptual learning by providing a definition, describing tent saturation: The case for a concept-based curriculum. Journal of

its uses, attributes, constructed cases, antecedents, and conse- Nursing Education, 46, 65-69.

quences. Conceptual learning is complex and therefore not eas- Giddens, J.F., Caputi, L., & Rodgers, B. (2015). Mastering concept-based

teaching: A guide for nurse educators. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier-Mosby.

ily measured, and it is important to know if conceptual learning Giddens, J.F., Wright, M., & Gray, I. (2012). Selecting concepts for a con-

is occurring. This concept analysis will assist educators in un- cept-based curriculum: Application of a benchmark approach. Journal

derstanding how learners conceptually learn, provide a refer- of Nursing Education, 51, 511-515. doi:10.3928/01484834-20120730-

ent for recognizing when conceptual learning is occurring, and 02

Guthrie, J., Van Meter, P., Hancock, G., Alao, S., Anderson, E., & McCann,

form the basis for the development of instruments to measure A. (1998). Does concept-oriented reading instruction increase strategy

conceptual learning and its outcomes. A definition of conceptu- use and conceptual learning from text? Journal of Educational Psychol-

al learning ensures consistent application in research and prac- ogy, 90, 261-278.

tice that promotes standardization, thereby reducing variation Institute of Medicine. (2010). The future of nursing: Leading change, ad-

and incomplete application of this type of learning. vancing health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Johnson, S. (1996, January 10). Learning concepts and developing intel-

An understanding of conceptual learning is essential because lectual skills in technical and vocational education. Paper presented at

many nursing programs are moving toward a concept-based the Jerusalem International Science and Technology Education Confer-

curriculum to address content overload in nursing education. ence on Technology Education for a Changing Future: Theory, Policy,

Because conceptual learning promotes enhanced synthesis, and Practice.

Jonassen, D. (1999). Designing constructivist learning environments. In

improved reasoning, and analysis skills, as well as increased C.M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional-design theories and models: A new

problem solving within nursing education, the Institute of Med- paradigm of instructional theory (Vol. 2, pp. 215-239). Mahwah, NJ:

icine’s (2010) recommendation was addressed to prepare learn- Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

ers to face the challenges of working in complex health care Lasater, K., & Nielsen, A. (2009). The influence of concept-based learning

environments. A consistent commitment to conceptual learning activities on students’ clinical judgment development. Journal of Nurs-

ing Education, 48, 441-446. doi:10.3928/01484834-20090518-04

will improve the competence of graduate nurses and their abil- Leonard, W.J., Gerace, W.J., & Dufresne, R.J. (1999). Concept based prob-

ity to translate theory into practice, which in turn will have a lem solving: Making concepts the language of physics [Technical re-

lasting significant impact on health care. port]. University of Massachusetts Physics Education Research Group,

Amherst.

Milne, D., Witten, I.H., & Nichols, D.M. (2007). A knowledge-based search

REFERENCES engine powered by Wikipedia. Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference

Anderson, L.W., & Krathwohl, D.R. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learn- on Information and Knowledge Management (pp. 445-454). New York,

ing, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educa- NY: ACM.

tional objectives. New York, NY: Pearson. Nielsen, A. (2016). Concept-based learning in clinical experiences: Bring-

Arslan, S. (2010). Traditional instruction of differential equations and con- ing theory to clinical education for deep learning. Journal of Nursing

ceptual learning. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications, 29, 94- Education, 55, 365-371. doi:10.3928/01484834-20160615-02

107. doi:10.1093/teamat/hrq001 Nielsen, A.E., Noone, J., Voss, H., & Matthews, L.R. (2013). Preparing

Ausubel, D.P., Novak, J.D., & Hanesian, H. (1978). Educational psychol- nursing students for the future: An innovative approach to clinical

ogy: A cognitive view (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Holt McDougal. education. Nurse Education in Practice, 13, 301-309. doi:10.1016/j.

Brandon, A.F., & All, A.C. (2010). Constructivism theory analysis and ap- nepr.2013.03.015

14 Copyright © SLACK Incorporated

Rodehorst, T.K., & Wilhelm, S.L. (2011). The inner-workings of conceptual Sutherland, R.D. (1969). Some thoughts on conceptual learning and infor-

learning in competency-based education. London, UK: Pearson Educa- mation retrieval [Published as broadside at Illinois State University].

tion. Retrieved from https://www.pearsoned.com/the-inner-workings- Retrieved from http://robertdsutherland.com/writings/conceptual_

of-conceptual-learning-in-competency-based-education/ learning.html

Smith, T.R., & Zeng, M.L. (2004). Building semantic tools for concept- Timpson, W., & Bendel-Simso, P. (2003). Concepts and choices for teach-

based learning spaces: Knowledge bases of strongly-structured models ing: Meeting the challenges in higher education. Madison, WI: Atwood.

for scientific concepts in advanced digital libraries. Journal of Digital Walker, L.O., & Avant, K.C. (2011). Strategies for theory construction in

Information, 4(4), 17. nursing (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Prentice Hall.

Journal of Nursing Education • Vol. 58, No. 1, 2019 15

Reproduced with permission of copyright owner. Further reproduction

prohibited without permission.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Inquiry ProcessDocument4 paginiInquiry Processapi-276379355Încă nu există evaluări

- More Examples of KR21 and KR20Document4 paginiMore Examples of KR21 and KR20Kennedy Calvin100% (1)

- The Impact of Learning Styles in Teaching EnglishDocument4 paginiThe Impact of Learning Styles in Teaching EnglishResearch ParkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design of A Full Adder Using PTL and GDI TechniqueDocument6 paginiDesign of A Full Adder Using PTL and GDI TechniqueIJARTETÎncă nu există evaluări

- PRDocument63 paginiPRJake Eulogio GuzmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 12 Relationship of Need and Motivation.Document10 paginiChapter 12 Relationship of Need and Motivation.John kevin AbarquezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mixed Method DesignDocument45 paginiMixed Method DesignEno RLÎncă nu există evaluări

- Distance Education 13MBDocument231 paginiDistance Education 13MBArianne Rose Fangon100% (1)

- Inquiry-Based Learning Literature ReviewDocument14 paginiInquiry-Based Learning Literature ReviewKimberlyAnnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hand-Outs For Action Research2Document10 paginiHand-Outs For Action Research2vanessa mananzanÎncă nu există evaluări

- AIINEDUCATIONDocument9 paginiAIINEDUCATIONOlavario Jennel PeloÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effects of Integrating Mobile Devices With Teaching and Learning On Students' Learning Performance - A Meta-Analysis and Research SynthesisDocument24 paginiThe Effects of Integrating Mobile Devices With Teaching and Learning On Students' Learning Performance - A Meta-Analysis and Research SynthesisVirgiawan Adi KristiantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teaching StrategiesDocument14 paginiTeaching Strategieseden barredaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Action Research Guide For Reflective Teachers: Fabian C. Pontiveros, JRDocument97 paginiAction Research Guide For Reflective Teachers: Fabian C. Pontiveros, JRJun Pontiveros100% (1)

- Action Research ReportingDocument58 paginiAction Research ReportingMaria Shiela Cantonjos MaglenteÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM) : A Model For Change in IndividualsDocument16 paginiThe Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM) : A Model For Change in Individualsmfruz80Încă nu există evaluări

- Kpi MR Qa QC SheDocument38 paginiKpi MR Qa QC SheAhmad Iqbal LazuardiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Multigrade Classroom Books1 7Document376 paginiMultigrade Classroom Books1 7Mark neil a. GalutÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding Educational TechnologyDocument12 paginiUnderstanding Educational Technologyargee_lovelessÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Are We Talking About When We Talk About Impact?Document22 paginiWhat Are We Talking About When We Talk About Impact?impactsp2Încă nu există evaluări

- 3 Chapter3 Methodology AndreaGorraDocument30 pagini3 Chapter3 Methodology AndreaGorraAris Nur AzharÎncă nu există evaluări

- KapoyyyyyyyyyyyyyDocument25 paginiKapoyyyyyyyyyyyyykim yrayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 1 Essay QuestionsDocument7 paginiModule 1 Essay QuestionsadhayesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Instructional Materials in Filipino Rhetoric: A Source of Educational Excellence in Filipino CurriculumDocument13 paginiInstructional Materials in Filipino Rhetoric: A Source of Educational Excellence in Filipino CurriculumJobelle CanlasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Concept Analysis of Interdisciplinary PDFDocument11 paginiConcept Analysis of Interdisciplinary PDFCharles JacksonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effective Use of Learning ObjectivesDocument6 paginiEffective Use of Learning ObjectivesIamKish Tipono ValenciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 15 Learning Theories in EducationDocument37 pagini15 Learning Theories in EducationERWIN MORGIAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study AnalysisDocument2 paginiCase Study AnalysisTanuj AroraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Special Topic MidtermDocument2 paginiSpecial Topic MidtermRosenda Naw-itÎncă nu există evaluări

- Concept Analysis of Managerial Coaching PDFDocument12 paginiConcept Analysis of Managerial Coaching PDFRomikoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2014 Qualitative Data Analysis After CodingDocument5 pagini2014 Qualitative Data Analysis After CodingAnonymous LsyWN2oJÎncă nu există evaluări

- 9 Transformative and MultiphaseDocument9 pagini9 Transformative and MultiphaseAC BalioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Improving Teacher-Student Interaction in The English Classroom An Action Research Report-IJRASETDocument5 paginiImproving Teacher-Student Interaction in The English Classroom An Action Research Report-IJRASETIJRASETPublicationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Distance Education TheoryDocument3 paginiDistance Education Theoryapi-235610494Încă nu există evaluări

- Teacher Education Around The World What Can We Learn From International Practice PDFDocument20 paginiTeacher Education Around The World What Can We Learn From International Practice PDFanne_karol6207Încă nu există evaluări

- Reaserch MethdologyDocument132 paginiReaserch Methdologymelanawit100% (1)

- 6 - Teaching-For-Understanding-And-Transfer-Of-Learning-CiocsonDocument30 pagini6 - Teaching-For-Understanding-And-Transfer-Of-Learning-Ciocsonapi-293598451Încă nu există evaluări

- Final ThesisDocument101 paginiFinal ThesisHazel Sabado DelrosarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theories of AttitudeDocument11 paginiTheories of Attituderomely1Încă nu există evaluări

- Everett Rogers' Diffusion of Innovations TheoryDocument4 paginiEverett Rogers' Diffusion of Innovations TheoryMagali Aglae Soule CanafaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Action Research Is Often Used in The Field of EducationDocument4 paginiAction Research Is Often Used in The Field of EducationLon GoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Change StrategyDocument3 paginiChange StrategyNeha JoshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sneha Nair CVDocument4 paginiSneha Nair CVGloria JaisonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bridging The Gap From Student Teacher To Classroom TeacherDocument11 paginiBridging The Gap From Student Teacher To Classroom TeacherGlobal Research and Development ServicesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effect of Classroom Management On2Document7 paginiThe Effect of Classroom Management On2Lukes GutierrezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factors Influencing The Academic Performance in Physics of DMMMSU - MLUC Laboratory High School Fourth Year Students S.Y. 2011-2012 1369731433 PDFDocument11 paginiFactors Influencing The Academic Performance in Physics of DMMMSU - MLUC Laboratory High School Fourth Year Students S.Y. 2011-2012 1369731433 PDFRon BachaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inquiry-Based Learning Literative ReviewDocument33 paginiInquiry-Based Learning Literative ReviewTrần thị mỹ duyênÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teori ChickeringDocument8 paginiTeori ChickeringNagarani KarappiahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enhancing Student Scientific Attitudes Towards Civic Education Lesson Through Inquiry-Based LearningDocument7 paginiEnhancing Student Scientific Attitudes Towards Civic Education Lesson Through Inquiry-Based LearningJournal of Education and LearningÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is CuriculumDocument15 paginiWhat Is CuriculumNissa Mawarda RÎncă nu există evaluări

- Complete 2Document31 paginiComplete 2Claire LagartoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Using Self-Determination TheoryDocument18 paginiUsing Self-Determination TheorySarah Jean OrenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical Thinking Final TermDocument54 paginiCritical Thinking Final TermM.Basit RahimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of The Concept of Successful Breastfeeding PDFDocument11 paginiAnalysis of The Concept of Successful Breastfeeding PDFAyu WulandariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roles of Teacher in Classroom ManagementDocument44 paginiRoles of Teacher in Classroom ManagementAthirah Md Yunus100% (1)

- Teaching and LearningDocument29 paginiTeaching and LearningGeok Hong 老妖精Încă nu există evaluări

- Action Research PosterDocument1 paginăAction Research Posterapi-384464451Încă nu există evaluări

- Student Engagement in Online LearningDocument5 paginiStudent Engagement in Online Learningapi-495889137Încă nu există evaluări

- Inquiring About InquiryDocument28 paginiInquiring About Inquiryapi-386385143Încă nu există evaluări

- Curriculum Studies Short NotesDocument7 paginiCurriculum Studies Short NotesPraveenNaiduÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Using A Modular Approach On Students Action ProposalDocument4 paginiEffects of Using A Modular Approach On Students Action ProposalNario Bedeser GemmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Short Guides in Education Research MethoDocument136 paginiShort Guides in Education Research MethoSchifosita Pusheena BlackÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nurse Education in Practice: Jaime L. Gerdeman, Kathleen Lux, Jean JackoDocument7 paginiNurse Education in Practice: Jaime L. Gerdeman, Kathleen Lux, Jean JackoChantal CarnesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anth 1020 Natural Selection Lab ReportDocument4 paginiAnth 1020 Natural Selection Lab Reportapi-272845435Încă nu există evaluări

- Psychology From Inquiry To Understanding Canadian 3rd Edition Lynn Test BankDocument38 paginiPsychology From Inquiry To Understanding Canadian 3rd Edition Lynn Test Bankvoormalizth9100% (12)

- Raj Yoga ReportDocument17 paginiRaj Yoga ReportSweaty Sunny50% (2)

- Problem Sheet V - ANOVADocument5 paginiProblem Sheet V - ANOVARuchiMuchhalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment 1 PDFDocument5 paginiAssignment 1 PDFAyesha WaheedÎncă nu există evaluări

- NIOS Configuration Class: Course SummaryDocument2 paginiNIOS Configuration Class: Course SummaryforeverbikasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical Issues in JournalismDocument5 paginiCritical Issues in JournalismChad McMillenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Optimization Module For Abaqus/CAE Based On Genetic AlgorithmDocument1 paginăOptimization Module For Abaqus/CAE Based On Genetic AlgorithmSIMULIACorpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Automatic Garbage Collector Machine: S. A. Karande S. W. Thakare S. P. Wankhede A. V. SakharkarDocument3 paginiAutomatic Garbage Collector Machine: S. A. Karande S. W. Thakare S. P. Wankhede A. V. Sakharkarpramo_dassÎncă nu există evaluări

- CDP Ex77Document36 paginiCDP Ex77bilenelectronics6338Încă nu există evaluări

- STOCHASTIC FINITE ELEMENT METHOD: Response StatisticsDocument2 paginiSTOCHASTIC FINITE ELEMENT METHOD: Response StatisticsRocky ABÎncă nu există evaluări

- Finalize Resume - ZetyDocument2 paginiFinalize Resume - ZetyAlok KulkarniÎncă nu există evaluări

- UTP PG Admission (Terms & Conditions) - Attachment 1 PDFDocument7 paginiUTP PG Admission (Terms & Conditions) - Attachment 1 PDFKhaleel HusainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Identification of The Challenges 2. Analysis 3. Possible Solutions 4. Final RecommendationDocument10 paginiIdentification of The Challenges 2. Analysis 3. Possible Solutions 4. Final RecommendationAvinash VenkatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theme of Otherness and Writing Back A Co PDFDocument64 paginiTheme of Otherness and Writing Back A Co PDFDeepshikha RoutrayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Class 8 - CH 12 Exponents Powers - Ws 2Document3 paginiClass 8 - CH 12 Exponents Powers - Ws 2Sparsh BhatnagarÎncă nu există evaluări

- FIRO Element B InterpretationDocument8 paginiFIRO Element B InterpretationchinadavehkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Families of Carbon Compounds: Functional Groups, Intermolecular Forces, & Infrared (IR) SpectrosDocument79 paginiFamilies of Carbon Compounds: Functional Groups, Intermolecular Forces, & Infrared (IR) SpectrosRuryKharismaMuzaqieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment Gravity and MotionDocument23 paginiAssignment Gravity and MotionRahim HaininÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mevlana Jelaluddin RumiDocument3 paginiMevlana Jelaluddin RumiMohammed Abdul Hafeez, B.Com., Hyderabad, IndiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Glickman (1) - Ethical and Scientific Implications of The Globalization of Clinical Research NEJMDocument8 paginiGlickman (1) - Ethical and Scientific Implications of The Globalization of Clinical Research NEJMMaria BernalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Linux CommandsDocument6 paginiLinux Commandsajha_264415Încă nu există evaluări

- Voyagers: Game of Flames (Book 2) by Robin WassermanDocument35 paginiVoyagers: Game of Flames (Book 2) by Robin WassermanRandom House KidsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture15 Analysis of Single PilesDocument32 paginiLecture15 Analysis of Single PilesJulius Ceasar SanorjoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exam 1Document61 paginiExam 1Sara M. DheyabÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reidblackman ChurchlandDocument8 paginiReidblackman ChurchlandYisroel HoffmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Prepare A Basic Training ModuleDocument7 paginiHow To Prepare A Basic Training ModuleSumber UnduhÎncă nu există evaluări