Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Position Paper Script v.1

Încărcat de

Rosario Perez Ocamia0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

19 vizualizări2 paginidfszd

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentdfszd

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

19 vizualizări2 paginiPosition Paper Script v.1

Încărcat de

Rosario Perez Ocamiadfszd

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 2

The Philippines has the highest number of college graduates among developing Asian

countries, but that isn’t a substitute for quality .

The role of education in economic development is widely acknowledged: education increases

the innovative capacity of an economy and facilitates the diffusion, adoption, and adaptation of

new ideas. More specifically, education increases the amount of human capital available,

thereby increasing productivity and ultimately output.Education is especially important in a

rapidly evolving economic environment where a rapid rate of job destruction and creation might

otherwise lead to a gap between the skills demanded in the labour market and the skills of job-

seekers. So how can regional cooperation improve the quality and availability of – and access to

– education? The role of regional cooperation in a particular country and what means of

cooperation are viable will largely depend on that country’s position on the development ladder

and the status of its education sector. Since 1975 both GDP and education levels in China,

Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam have been catching up. Over the same period GDP

growth and improvements to education levels have been losing momentum in developed

countries including the United States, Canada, and New Zealand. The Philippines exhibits a

curious pattern in this respect, because even as the level of education attainment plateaued, its

GDP has been falling behind. This is an apparent contradiction. Given the well-established

beneficial effects of education on GDP and on GDP growth rates, the Philippines should have

witnessed an era of high growth since 1975, when it had the highest rate of completion of

tertiary education among developing Asian countries – higher than Japan, South Korea, Taiwan,

or Singapore. This suggests that the problem in the Philippines has been the quality of

education, rather than its availability or accessibility. Regional cooperation in education is often

identified with trade in education services. In the Asia Pacific, this most commonly takes the

form of direct exchanges of people, whether they be students from less-developed countries

going to study in more-developed ones, or, as in the case of Singapore and Malaysia,

academics from more-developed countries encouraged to relocate to universities in less-

developed countries by partnerships between the two institutions. Trade in education services

also takes place through transnational education, for example when foreign institutions are

encouraged to establish campuses in developing countries. Yet these forms of cooperation are

not the most appropriate for the Philippines – for instance because poor local infrastructure

makes it difficult to attract foreign institutions and academics. And, moreover, the principal effect

of these forms of education cooperation is to make education more available, when the problem

in the Philippines is the quality of education – not its availability. Regulatory reform is needed to

ensure that the quality of education received at home is high enough to give domestic Filipino

students access to education and work abroad. This reform process must start by establishing a

credible accreditation system, because under the current system of voluntary self-regulation,

less than 20 percent of higher education institutions in the Philippines are accredited. Forms of

international cooperation other than through trade in education services would allow the

Philippines to improve the quality of domestic education by following the example set by

Malaysia, which has linked its own accreditation system to international ones. Malaysia has also

been active in promoting the development of a regional quality assurance framework, the

ASEAN Quality Assurance Network (AQAN). The AQAN was organized in 2008 in order to

promote collaboration among quality assurance agencies in individual ASEAN countries.

Though the Philippines has not yet fully acceded to the AQAN, negotiations are underway to

formalize an agreement to adopt common standards in the education sector. The Philippines

can also pursue bilateral mutual recognition agreements. Such agreements should include

quality assurance on the part of both countries. In this way, even if the standards are not at the

same level as in higher-income countries, there will be pressure on some of the higher

education institutions in the Philippines to improve their programs and facilities in order to gain

accreditation. Such agreements, whether bilateral or as part of the AQAN, might make it easier

for Filipino policy makers to argue for domestic reform on the basis that it is necessary to meet

international agreements. With a higher-quality higher education system, the Philippines would

then be better placed to reap the well-documented economic benefits of an educated

population.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Validity of Impact Analysis InstrumentDocument24 paginiValidity of Impact Analysis InstrumentRosario Perez OcamiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Criteria and Indicators With Corresponding Points in The Selection and Ranking For Master TeachersDocument2 paginiCriteria and Indicators With Corresponding Points in The Selection and Ranking For Master TeachersRosario Perez OcamiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mathematics: Quarter 3Document15 paginiMathematics: Quarter 3Rosario Perez OcamiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Department of EducationDocument10 paginiDepartment of EducationRosario Perez OcamiaÎncă nu există evaluări

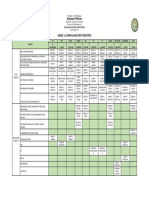

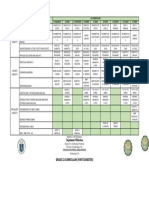

- SHS Curriculum Class ScheduleDocument4 paginiSHS Curriculum Class ScheduleRosario Perez OcamiaÎncă nu există evaluări

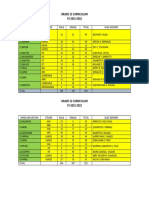

- Class Program Grade 11 CurriculumDocument1 paginăClass Program Grade 11 CurriculumRosario Perez OcamiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Class Program Grade 12 CurriculumDocument1 paginăClass Program Grade 12 CurriculumRosario Perez OcamiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- K - 12 Subjects For SHSDocument1 paginăK - 12 Subjects For SHSRosario Perez OcamiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Input Data Sheet For SHS E-Class Record: Learners' NamesDocument8 paginiInput Data Sheet For SHS E-Class Record: Learners' NamesRosario Perez OcamiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- SHS No. of LearnersDocument1 paginăSHS No. of LearnersRosario Perez OcamiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Curriculum EssentialsDocument17 paginiCurriculum EssentialsRosario Perez Ocamia100% (3)

- Zamboangacity State Polytechnic College Graduate SchoolDocument25 paginiZamboangacity State Polytechnic College Graduate SchoolRosario Perez OcamiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Health Assessment Form ConsolidatedDocument1 paginăHealth Assessment Form ConsolidatedRosario Perez OcamiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medical CertificateDocument1 paginăMedical CertificateRosario Perez OcamiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Human Resource DevelopmentDocument14 paginiHuman Resource DevelopmentRosario Perez Ocamia100% (1)

- Curriculum Essentials Part 2Document45 paginiCurriculum Essentials Part 2Rosario Perez OcamiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zamboangacity State Polytechnic College Graduate SchoolDocument21 paginiZamboangacity State Polytechnic College Graduate SchoolRosario Perez Ocamia100% (1)

- Introduction To Quanti Research PDFDocument1 paginăIntroduction To Quanti Research PDFRosario Perez OcamiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PR 2 CGDocument2 paginiPR 2 CGRosario Perez OcamiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Strategic Plan - 7.14Document11 paginiStrategic Plan - 7.14Anonymous 56qRCzJRÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5Document74 pagini5Chendri Irawan Satrio NugrohoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anna Cabell Readingwriting BackgroundDocument3 paginiAnna Cabell Readingwriting Backgroundapi-283881062Încă nu există evaluări

- 07 Moral Education 20GENF1Document19 pagini07 Moral Education 20GENF1Ketan KhairwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Icf 2 Performance Task Portfolio 2023 2024Document7 paginiIcf 2 Performance Task Portfolio 2023 2024marcleonor032Încă nu există evaluări

- Activity 2Document1 paginăActivity 2Eleah CaldozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Principles Develop Entrepreneurship IN SCHOOL?: A Literature ReviewDocument24 paginiHow Principles Develop Entrepreneurship IN SCHOOL?: A Literature ReviewPutri Ayu A. S.Încă nu există evaluări

- Schizophrenia BiopsihosocialDocument401 paginiSchizophrenia BiopsihosocialPetzyMarian100% (1)

- Non Metropolitan Cities (Class I) of India - HUDCO Phase IDocument257 paginiNon Metropolitan Cities (Class I) of India - HUDCO Phase IRohitaash DebsharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Education (Elementary & Secondary) Department Government of Assam Gunotsav 2022 Student Report CardDocument41 paginiEducation (Elementary & Secondary) Department Government of Assam Gunotsav 2022 Student Report CardAjan BaishyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Money Lesson Plan For First GradeDocument5 paginiMoney Lesson Plan For First Gradeapi-248046422Încă nu există evaluări

- Planificare-unitatea-4-A Space Trip, XL in Concert!, A Happy PersonDocument2 paginiPlanificare-unitatea-4-A Space Trip, XL in Concert!, A Happy PersonOrtansa Madelen GavrilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- தகவல் தொழில்நுட்ப வளர்ச்சிDocument7 paginiதகவல் தொழில்நுட்ப வளர்ச்சிVasantha Kumari100% (1)

- 2010-2011 Utah Educational DirectoryDocument195 pagini2010-2011 Utah Educational DirectoryState of UtahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Australia' PDFDocument3 paginiAustralia' PDFBaran ShafqatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revision Test PDFDocument8 paginiRevision Test PDFLai Kee KongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Horse SenseDocument49 paginiHorse SenseMona Lall100% (2)

- Analysis of Book Rich Dad Poor DadDocument7 paginiAnalysis of Book Rich Dad Poor DadAnas KhurshidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Napcon 2021012opDocument377 paginiNapcon 2021012opvishalÎncă nu există evaluări

- BE Ist Year Sem 1 and 2 - Full Scheme With Syllabus & SU CodeDocument86 paginiBE Ist Year Sem 1 and 2 - Full Scheme With Syllabus & SU CodePÀRMAR parthÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 1 Examples of Supply ChainsDocument53 paginiLecture 1 Examples of Supply ChainsAwais (F-Name Jan Muhammad)Încă nu există evaluări

- Srishti Gupta: Citizenship: Indian Date of Birth: 15 March 1990Document2 paginiSrishti Gupta: Citizenship: Indian Date of Birth: 15 March 1990Pankaj Yog BhartiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revised SBM Assessment ToolDocument12 paginiRevised SBM Assessment ToolRuel SariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kindergarten Model Curriculum For Mathematics PDF 1Document18 paginiKindergarten Model Curriculum For Mathematics PDF 1Zizo ZizoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ra-013111 Real Estate Broker Davao 4-2024Document7 paginiRa-013111 Real Estate Broker Davao 4-2024R O NÎncă nu există evaluări

- Admission Procedure 12Document4 paginiAdmission Procedure 12Rahul JaiswarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Library CommitteeDocument3 paginiLibrary CommitteeChristine Dianne MacuroÎncă nu există evaluări

- BandagingDocument3 paginiBandagingMelery LaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding The Self: Self From Various Perspectives (Philosophy)Document54 paginiUnderstanding The Self: Self From Various Perspectives (Philosophy)nan nan100% (2)

- IELTS SPEAKING Sample QuestionsDocument38 paginiIELTS SPEAKING Sample QuestionsJovelyn YongzonÎncă nu există evaluări