Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

GCQRI Lit Review

Încărcat de

gcqriDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

GCQRI Lit Review

Încărcat de

gcqriDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Draft Copy

FACTORS INFLUENCING CUP

QUALITY IN COFFEE

Photo Courtesy of SPREAD, Rwanda

Prepared for the First Coffee Quality Congress of the Global Coffee Quality

Research Initiative

Brian Howard

October, 2010

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 1

Draft Copy

The quality of coffee is extensive in its de@i‐

FACTORS IN- nition. Leroy et al, 2006 de@ines coffee

quality on a number of levels. At the ex‐

F L U ENCING CUP porter or importer level coffee quality is

linked to bean size, number of defects,

Q UALITY IN regularity of provisioning, tonnage avail‐

able, and physical characteristics. At the

COF F EE roaster level coffee quality depends on

moisture content, characteristic stability,

October, 2010 origin, organoleptic (taste and smell) quali‐

ties and biochemical compounds. At the

consumer level coffee quality is about taste

Introduction and @lavor, effects on health and alertness,

geographical origin, and environmental

and sociological considerations. At every

link in the supply chain there is the consid‐

eration of price. In 2004 the International

Organization for Standardization (IOS) de‐

@ined a standard for green coffee quality

which entails defects, moisture content,

size, and some chemical compounds of

beans as well as standardization of prepa‐

ration of a sample from which to perform

cup tasting.

Photo Courtesy SPREAD Rwanda

Agronomy:

Cup quality in coffee is affected by a great

number of factors; agronomic, genetic and

Soil Nutrition

production related. In this review the

author seeks to summarize the major @ind‐

Coffee can be cultivated on a wide variety

ings of the research that has been con‐

of soil types, provided these are at least 2

ducted that is speci@ically related to cup

meters deep, free‐draining loams with a

quality and how it is affected by the envi‐

good water retention capacity and a pH of

ronment in which the coffee tree is grown,

5‐6, fertile and contain no less than 2% or‐

the genetic makeup of the coffee plant itself

ganic matter. High quality, acidic Arabica

and the manner in which coffee is prepared

coffees tend to be produced on soils of vol‐

for consumption. More than 800 aromatic

canic origin.

compounds combine to give acidity, body

and aroma to a cup of coffee. These three

Van Der Vossen, 2005 expresses concern

descriptors will serve as the parameters

that, “to sustain economically viable yield

around which cup quality is described in

levels, 1 ton green coffee per hectare (4.5

this document.

acres) per year, large additional amounts of

composted organic matter will have to

come from external sources to meet nutri‐

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 2

Draft Copy

ent requirements, especially nitrogen & po‐

tassium. The majority of small land hold‐

Fertilizer

ers will not be able to acquire the neces‐

sary quantities and will be confronted with Organic vs Inorganic Fertilizer

declining yields. Organic farming does not

necessarily prevent disease or pests below Organic production of coffee is often

economically harmful thresholds and the thought preferable due to the strong poten‐

humid conditions of heavily shaded coffee tial of negative environmental impacts

may actually stimulate the outbreak of oth‐ from fertilizer leaching into surface waters

ers. and groundwater. However, any produc‐

tion crop signi@icantly depletes its soils

Vaast et al, 1998 found that total uptake of ability to replenish key nutrients and hu‐

nitrate (N03) and ammonium (NH4), key mic matter taken from it in the form of

nutrients for plant growth and develop‐ produce. Inorganic fertilizer is often ap‐

ment and the limiting nutrient in Arabica plied at rates approaching 100 to 300 kilo‐

Coffee, at any ratio was higher than that of grams per hectare at signi@icant expense to

plants fed solely with nitrate or ammonium producers. (Carvajal, 1959) Because of the

alone. Anaerobic, lack of oxygen, soil con‐ preference for organically produced pro‐

ditions reduced nitrate and ammonium up‐ duce, especially in the specialty coffee

take by 50% and 30% respectively and the market, solutions for such a de@icit must be

presence of dinitrophenol almost com‐ found and implemented in regionally ap‐

pletely inhibited N uptake in any form. propriate ways.

Vaast suggests that these results indicate

that Arabica coffee is well adapted to acidic In the shaded Indian coffee terrior of Kar‐

soil conditions and can effectively utilize nataka, India Nagaraj et al., 2006 found

the seasonally available forms of inorganic that the addition of inorganic potassium in

nitrogen (N). These observations can help the form of muriat of potash and sulphate

to optimize coffee nitrogen nutrition by of potash had the effect of increased coffee

suggesting agricultural practices that main‐ yields over the period of four years at a

tain root systems in the temperature range rate of approximately 15%. The difference

that is optimum for both ammonium and between the two treatment methods out‐

nitrate uptake. Vaast found that both ni‐ lined by Nagaraj not being statistically sig‐

trate and ammonium uptake peaked when ni@icant. It should be noted that the soils in

root systems were maintained at 34 de‐ which this coffee were planted were receiv‐

grees Celsius. Below this temperature ing approximately 40 to 60 kg of potassium

plant color indicated a loss of vigor. There‐ per hectare per year in leaf fall. The study

fore both nitrate and nitrite availability in indicated that no consistent trend could be

soi, as well as the coffee trees capacity for observed in the cup evaluation report for

uptake through ideal temperature regimes, three years. Cup quality of Arabica coffee

can be maximized. Van Der Vossen, 2009 was found to be similar in both MOP and

notes that excessive calcium and potassium SOP treated plots but that there was a

in soils produce a hard and bitter tasting modest improvement in the cup quality of

liquor. robusta coffee in the sulphate potash

treated plots compared to muriate of pot‐

ash applications in the second and third

years. It should be noted that there has not

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 3

Draft Copy

been any evidence of changes occurring in proximately 20% of their nitrogen from the

the @lavour compounds due to agronomic biological nitrogen @ixation occurring via

use of sulphur or otherwise. (Krishnamur‐ symbiosis with I. oerstediana. No estimate

thy Rao, 1989) Studies conducted in Kenya could be derived for plots between 5 and 7

by (Njoroge and Mwakha, 1985) did not years. It is a reasonable assumption to

note any difference in liquor quality of cof‐ make that greater availability and uptake of

fee between NPK fertilized plots and con‐ soil nitrogen has a strong positive correla‐

trol treatment over eleven years of re‐ tion to cup quality via plant health and

search. bean size.

Cup quality differences have been found in

studies contrasting organic and inorganic

fertilization. In a 2008 study undertaken

by Malta, et al. no signi@icant differences Environmental Factors

were observed on the cup quality among

beans from conventional and organic Shade vs Sun

plants in the @irst year. However in the sec‐

ond year, cup quality of some organic Bosselmann et al., 2009 in Huila, Colombia

treated plants was superior when com‐ found that sensory attributes were in@lu‐

pared to conventionally treated plants. A enced negatively by shade, and that physi‐

positive effect on sensorial attributes was cal attributes were in@luenced positively by

observed using cattle manure, either alone altitude. In higher altitudes (approxi‐

or associated with coffee straw and green mately 1700 meters above sea level) shade

manure. had a negative effect on fragrance, acidity,

body, sweetness and preference of the bev‐

In Hawaii, Youkhana & Idol, 2009 found erage, while no effect was found on the

that the addition of mulch from shade tree physical quality of the bean. At lower alti‐

pruning signi@icantly offset net nitrogen tudes, shade did not have a signi@icant ef‐

and carbon losses from coffee cultivation. fect on sensorial attributes, but signi@i‐

Improved carbon and nitrogen sequestra‐ cantly reduced the number of small beans.

tion in soil was measured over two years At high altitudes with low temperatures

and it was found that soil bulk density did and no nutrient or water de@icits, shade

not decline in mulched plots as opposed to trees may have a partly adverse effect on C.

signi@icant changes in bulk density for un‐ Arabica cv Caturra resulting in reduced

mulched plots. sensory quality. The occurrence of berry

borer (Hypothenemus hampei) was lower

Grossman et al., 2006 found that organic at high altitudes and higher under shade.

production standards are being met while Bosselman goes on to suggest that future

available Nitrogen in soil is supplemented studies on shade and coffee quality should

by nitrogen @ixing shade trees. Biological focus on the interaction between physical

Nitrogen Fixation is facilitated through the and chemical characteristics of beans.

use of leguminous shade trees in the genus

Inga with the most signi@icant results found A study was done in Costa Rica by Vaast et

in 1 to 3 year old plots of C. Arabica and I. al., 2005 contrasting light regimes and op‐

oerstediana. In these young plots it was timal coffee growing conditions on dwarf

found that coffee trees were deriving ap‐ coffee, Coffea Arabica. Shade was found to

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 4

Draft Copy

decrease coffee tree productivity by 18% Vossen concurs that shade has a positive

but reduced alternate bearing. Shade also effect on coffee quality, particularly at me‐

positively affected bean size and composi‐ dium altitudes but also reduces yields. He

tion as well as cup quality due to a delay in also found that at altitudes above 1800 me‐

berry @lesh ripening by up to a month. ters shade did not improve cup quality.

Higher levels of sucrose, chlorogenic acid

and trigonelline in sun grown beans indi‐

cated incomplete bean maturation and re‐ Rainfall & Irrigation

sulted in higher bitterness and astringency

in cup quality. Higher fruit loads, which Van Der Vossen states that rainfall re‐

can be mitigated through branch thinning, quirements for Arabica coffee production

reduced bean size owing to carbohydrate are at least 1200mm per year with a

competition among berries during bean maximum of 2500mm. He contends that

@illing. Higher taste preferences were coffee plants grow and yield better if ex‐

linked to lower fruit load. Shade was also posed to alternate cycles of wet and dry

found to mitigate negative attributes in cof‐ seasons and that a period of water de@icit is

fee quality like bitterness and astringency helpful in synchronizing @lower bud differ‐

while positive attributes like acidity were entiation. Areas with precipitation in ex‐

found to be signi@icantly higher in shade cess of 2500mm have the tendency to pro‐

grown beans. A noteworthy aspect of this duce lower quality coffee due to irregular

study was that the overall beverage quality, cherry ripening and poor bean drying con‐

higher acidity, lower astringency and ditions after harvesting. On the other end

higher preference, was found to be higher of the spectrum in drought years shoot

in the year 2000 when production was dieback and premature ripening of the ber‐

around 30% lower than in 1999. ries can result in light beans producing a

liquor with immature and astringent notes.

Geromel et al, 2008 builds his study on the

effects of shade on the development and Da Silva et al, 2005 investigated the in@lu‐

sugar metabolism of Coffea Arabica L. on ence of environmental conditions and irri‐

the premise that coffee fruits grown in gation on the chemical composition of

shade are characterized by larger bean size green coffee beans and the relationships of

than those grown under full sun condi‐ those parameters to the quality of the bev‐

tions. Bean size, as noted, is a strong con‐ erage according to both sensorial and elec‐

tributor to cup quality. He found that tronic analysis. He found that irrigation

shade led to a signi@icant reduction in su‐ was not a major factor affecting chemical

crose content and to an increase in reduc‐ composition since there were few differ‐

ing sugars. In pericarp and perisperm tis‐ ences in relation to non irrigated coffee

sues, higher activities of sucrose synthase plants. He found the production site tem‐

and sucrose phosphate synthase were de‐ perature differentials to be the main in@lu‐

tected at maturation in the shade com‐ encing factor on biochemical composition.

pared with full sun and that both enzymes The study was undertaken near Sao Paulo,

also had higher peaks of activities in devel‐ Brazil and the major @inding was that cup

oping endosperm under shade than in full quality decreased as air temperature rose

sun. Geromel went on to suggest that to about 3.5 degrees above the optimum

metabolic pathways for sucrose needed limit for coffee cultivation at 18 to 21 de‐

further study for identi@ication. Van Der

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 5

Draft Copy

grees Celsius. Similar @indings are reported induce slower growth and more uniform

by Decazi et al., 2003 in Argentina. ripening of the berries, and produce larger

and denser beans. Bean size and density is

In a study done in Australia between 2000‐ often correlated to aroma, @lavor and supe‐

2002 by David Peasley of Rural Industries rior beverage quality. Altitude also tends

Research, irrigation was found to signi@i‐ to have a positive effect on acidity while

cantly increase bean yield as well as pro‐ reducing bitterness.

duce the following results under interna‐

tionally recognized SCAA cupping forms.

The non irrigated control crop scored a 69 Slope

with the description of “low acidity and

mild smoky @lavour and thin body.” The East facing slopes were found by Avelino et

low water stressed irrigated treatment al., 2005 to yield beverages with generally

scored 73 with the description of “dull superior attributes, probably because of

bakey aroma, nice acidity, sour, green apple superior exposure to morning sunlight.

@lavor.” The medium water stressed irri‐ The beverages from east facing slopes were

gated treatment scored 75.5 with the de‐ mainly more acid, with a score of 2.73 out

scription of “faint but sweet aroma, juicy, of 5, in the higher quality terriors, as op‐

citrus @lavour, OK body.” Each of the three posed to 2.36 out of 5 for other exposures.

areas received 1634mm of rainfall with the In addition a positive relation was found

low water stressed irrigated area having between altitude and taster preferences.

2100mm of irrigation applied to it and the

highly water stressed irrigated area having Laderach & Vaast et al. in their “Geographi‐

647mm of irrigation applied to it. cal Analyses to Explore Interactions be‐

tween Inherent Coffee Quality and Produc‐

tion Environment” state that increasing

Temperature & Altitude slope negatively in@luenced the @inal score

of cup quality from terriores on two test

Decazy et al, 2003 found that Honduran sites in Columbia and Nicaragua.

coffees of superior quality came from high

altitudes, above 1000m, where rainfall re‐

mains relatively low, that is to say below

1500mm per year. It was found that a

strong inverse relation between rainfall Genetics:

and fat content exists and that this relation

needs to be considered in relation to alti‐ With total economic damage to coffee

tude because in the sampled regions in crops mounting to an estimated US $2‐2.5

Honduras, rainfall and altitude were found billion annually, coffee leaf rust and coffee

to be inversely correlated. High altitude berry disease affect a signi@icant portion of

green coffee beans had a higher fat content the supply chain. In addition to increased

than lower altitude beans and gave a better scarcity due to disease and fungus signi@i‐

cup quality. Van Der Vassen stresses that cant environmental hazards exist due to

high altitudes are critical for the successful the copper based fungicides used to @ight

production of high quality Arabica coffees Coffee Berry Disease and Coffee Leaf Rust

in equatorial regions. Lower temperatures, chemically. (Van Der Vossen, 2009) Ac‐

and their longer daily amplitudes, tend to cording to Walyaro, 1997 the aim of most

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 6

Draft Copy

genetic improvement programs is disease tion’ s annual report for 1987‐1988 in Af‐

resistance and quality. Determination of rica as a whole losses can range between

berry and bean characteristics using plant 30% and 50% during very high precipita‐

breeding is relatively simple, aroma and tion years even with chemical treatment.

@lavor attributes present signi@icantly

greater dif@iculties due to their chemical Fusarium (Giberella) stilboides (Fusar‐

complexity and susceptibility to agronomic ium bark disease) is a pathogen that causes

variability. Walyaro goes on to postulate bark lesions which are a result of damage

that the development of reliable lab proce‐ to the vascular system. Vascular wilt often

dures which relate individual chemical results in the death of the entire tree. Fu‐

compounds to cup quality could have im‐ sarium is reported to have almost killed the

portant bearing on genetic improvement of entire coffee industry in Malawi in the late

cup quality in coffee. It has been shown 1970’s according to Siddiqi, 1980.

that resistance to disease and nematodes

can be increased through genetic exchange Genetic modi@ications have in some cases

between C. Arabic and C. canephora. (Ber‐ affected cup quality adversely but in many

trand et al., 2005, Dessalegn et al., 2008, cases have not adversely affected cup qual‐

Leroy et al., 2006) The greater debate and ity and increased genetic resistance to cof‐

perhaps of more importance to the topic of fee leaf rust and M. exigua by introducing

cup quality is whether this genetic resis‐ genetic material into the Arabica plant

tance will lower overall cup quality by ne‐ from C canephora via the Timor hybrid.

cessity and in the end decrease consumer (Leroy et al., 2006) There are regional

experience. variations in resistance to disease that can

be exploited while maintaining or improv‐

ing beverage quality as is noted by Anzueto

Major Diseases: et al., 2001. Anzueto remarks that Ethio‐

pian origins provide resistance to nema‐

Coffee leaf rust (CLR) is caused by a todes and partial resistance to leaf rust and

pathogen of the leaf called Hemileia vas‐ likely improve beverage quality.

tarix and is characterized by orange rust

postules on the under side of the leaf. This In higher quality C. Arabica stocks the main

pathogen causes signi@icant losses as a re‐ goal seems to be in the area of improve‐

sult of loss of leaf area and the correspond‐ ment of resistances to pathogens and an

ing loss of photosynthesis and leaf drop. increasing of yield. Overall the global level

Coffee leaf rust has now spread through all of introgression of alien genetic material,

Arabica coffee producing countries in the material from C. canephora, does not seem

world making it a signi@icant issue for the to be linked to variation in cup quality.

coffee industry as a whole in terms of sup‐ (Leroy et al., 2006) Bertrand et al., 2003

ply susceptibility. came to similar conclusions when he stated

that selection can avoid accompanying the

Coffee berry disease (CBD) is caused by introgression of resistance genes with a

Colletotrichum kahawae and is a fungus drop in beverage quality due to positive

that causes dark lesions on the green and results in approximately half of the trials

ripening berries. CBD is unique in that that he carried out dealing with taste char‐

crop losses due to the fungus can be severe. acteristics such as sucrose content and

According to the Coffee Research Founda‐ beverage acidity.

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 7

Draft Copy

ences between Arabica hybrids and tradi‐

In order to avoid damage to roots from tional cultivars. Bertrand goes on to note

nematodes, C. Arabica is commonly inter‐ that “new hybrid varieties with high bever‐

grafted onto C canephora. The perform‐ age quality and productivity potential

ance of such grafts was evaluated over 5 should act as a catalyst in increasing the

years in Costa Rica by Bertrand et al., 2001. economic viability of coffee agroforestry

The grafting did not have an appreciable systems being developed in Central Amer‐

effect on caffeine, fat and sucrose contents. ica.

However the C. Liberica rootstocks did sig‐

ni@icantly reduce aroma and the size of the Van Der Vossen, 2009 points out that tradi‐

bean produced. These de@iciencies were tional cultivars of Arabica coffee are sus‐

partially explained however by tissue in‐ ceptible to coffee leaf rust and coffee berry

compatibility at the graft level. F1 hybrids disease. CLR being of worldwide impor‐

of C. Arabica with 7 to 22% genetic mate‐ tance while CBD remains restricted to Af‐

rial from C. canephora have been shown by rica. Van Der Vossen contends that there is

Bertrand et al., 2006 to produce good cup a mounting volume of scienti@ic evidence

quality under ideal conditions and in about accumulated over many years showing

half of the tested strains. that, given optimum environmental factors,

disease resistant cultivars can in fact pro‐

With approximately a 10% market share of duce coffee of equal quality to those from

the total coffee consumed world wide, de‐ the best traditional varieties.

caffeinated coffee is being considered as a

genetic trait. Consideration of genetic di‐

versity and the correlation of caffeine con‐

tent in relation to cup quality was looked at

speci@ically by Dessalegn et al., 2008. Des‐ Quality Evaluation

salegn found that Ethiopian genotypes of Methods

low caffeine content typically showed a

lower cup quality but that there were no‐

The successful integration of genetic traits,

table exceptions. Consequently he con‐

which add positive taste characteristics as

cludes that simultaneous selection for low

caffeine content and good cup quality is

possible given that there are sources of de‐

sirable genes in terms of cup quality with

relatively low caffeine content that can be

utilized for resistance breeding.

Bertrand et al., 2006 in Central America

found homeostasis, stable equilibrium, in

taste characteristics of Arabica hybrids for

which bean biochemical composition was

less affected by elevation than that of the

traditional varieties. The organoleptic

evaluation of hybrids, which was per‐

formed on samples originating from high

elevation, showed no signi@icant differ‐ Photo of Cupping Courtesy SPREAD, Rwanda

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 8

Draft Copy

well as contribute to the robustness of cof‐ bica tree that has been introgressed with C

fee trees in relation to their susceptibility canephora genes. Spectra taken from near‐

to disease and pests, can yield signi@icant infrared re@lectance of green coffee were

desirable results in terms of supply chain capable, by principal component and fac‐

security and cup quality. DNA introgres‐ toral discrimination, of correctly classifying

sion of alien genetic material is being car‐ beans into categories of introgressed or

ried out world wide with varying and non‐introgressed with degrees of accuracy

highly disputed results. Discussion of vari‐ from 92.3% to 94.87%. This type of analy‐

ous quality evaluation methods to deter‐ sis may serve coffee buyers or roasters as

mine the extent of gene introgression is a they seek to distinguish between non in‐

key component of genetic research. Coffee trogressed Arabicas and genotypes carry‐

identi@ication and classi@ication serves as a ing chromosome fragments of C canephora

means to avoid coffee adulteration due to genetic material which could produce po‐

the variability of @inal sale prices depend‐ tentially negative affects on cup quality.

ing on coffee origin and variety with prices Posada et al., 2009 concurs that a near in‐

of pure Arabica achieving prices upwards frared spectroscopy signature that has

of 25% over robusta coffees. been acquired over a set of harvests can in

fact effectively characterize a coffee variety.

Posada hypothesizes that the spectral sig‐

Near Infrared Re@lectance nature is affected by annual environmental

factors but that through multiple harvest

Near Infrared Re@lectance (NIRS) is based calibration data can be made useful for

on the absorption of electromagnetic radia‐ practical application to breeding.

tion by matter. This method of analysis al‐

lows for the extraction of a large amount of

information concerning biochemical com‐

position and is used extensively in a num‐

ber of crops. This ability to quickly extract The Science of Taste

a great deal of information makes NIR a

highly cost effective source of information Chemical composition in relation to pre‐

for researchers and coffee buyers and established cup quality:

roasters.

Attributes of green coffee beans, both bean

In today’s marketplace coffee identi@ication density and volume, were higher for softer

and classi@ication is as crucial to cup qual‐ tasting samples as opposed to the rio off

ity as it is to consumer requirement for @lavored samples according to a study done

origin and species speci@ication. In order by Franca et al., 2004. The rio sample pre‐

to obtain top market prices, methods of ef‐ sented lower lipid contents, most likely as‐

@icient, inexpensive, and highly accurate sociated with the presence of defective

identi@ication of coffee origins and charac‐ beans. Acidity increased and pH levels de‐

teristics are paramount. creased as cup quality decreased likely due

to the effect of defective beans which had

NIRS appears to be a method that Bertrand undergone fermentation. After roasting,

et al., 2005 & Posada et al., 2009 have the rio sample presented higher density

shown to be ef@icient for determining and trigonelline levels, indicating that it

whether a green coffee comes from an Ara‐

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 9

Draft Copy

had not roasted to the same degree as the Molecular Markers

other samples tested.

Molecular markers are widely used,

through traditional chemical analysis, to

“Each of the main reserve compounds of investigate canephora and liberica gene

the bean (parietal polysaccharids, lipids, introgression into Arabica lines as a resis‐

proteins, sucrose) as well as secondary me‐ tance to pests and diseases. Coffee ampli‐

tabolites (Chlorogenic acids, caffein, @ied fragment length, polymorphism and

trigonelin...) play a central role in chemical simple sequence repeats have been used to

reactions during roasting. We believe that analyze the introgressions mentioned

deciphering the correspondent metabolic above. Villareal et al., 2009 found fatty ac‐

pathways are the key to better understand‐ ids in particular have proven effective for

ing quality and the use of biomarkers for the discrimination of Arabica varieties and

breeding. On the other hand, volatile com‐ speci@ic growing terriors. Crop to crop en‐

ponents, mainly from phenylpropanoids vironmental factors where found to have a

and isopropenoids, are synthesized during signi@icant impact on fatty acid content and

bean maturation. Even very low quantities thus limit discrimination to moderate ef@i‐

(nano‐mole) might strongly in@luence cup ciency across a number of years. Posada et

quality. We have two ongoing preliminary al., 2009 also found that correct classi@ica‐

works (to be published) in which we have tion and discrimination among different

been studying the in@luence of environ‐ varieties of introgressed genetic material

ment and genetics on cup quality pro@iles was possible through traditional chemical

(metabolic @ingerprints) using the SPME analysis to the tune of 79% accuracy. He

GC‐MS technology.” also found in the same study that using

spectral signatures in green beans pro‐

‐‐Dr. Christophe Montagnon of CIRAD, per‐ vided 100% correct differentiation among

sonal correspondence varieties.

Joet et al, 2010 examined the in@luences of Farah et al., 2005 investigated Brazilian

environmental factors and wet processing green and roasted coffee beans for correla‐

on the lipid, chlorogenic acid, sugar and tions between cup quality and levels of su‐

caffeine content of green Arabica beans. crose, carreine, trigonelline and chloro‐

Each of these biochemical markers repre‐ genic acids as determinded by HPLC analy‐

senting key components of cup quality. He sis. They found that trigonelline and

found that chlorogenic acids and fatty acids 3.4‐dicaffeoylquinic acid levels in green

in the bean were controlled by the average and roasted coffee correlated strongly with

air temperature during bean development. high quality. To some extent caffeine levels

However, total lipid, total soluble sugar, to‐ were found to be associated with good

tal polysaccharide and total chlorogenic quality. The amount of defective beans, the

acid contents were not all in@luenced by the levels of caffeoylquinic acids, feruloylquinic

climate in which beans were produced. acids and their oxidation products were

Glucose content was positively affected by associated with poor cup quality and the

altitude and sorbitol content after wet Rio‐off‐@lavor. Similar correlations be‐

processing was directly dependent on glu‐ tween cup quality and chemical attributes

cose content in fresh beans. were observed in green and light roasted

samples which indicates that chemical

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 10

Draft Copy

analysis of green beans may be used as an tation may improve @lavor marginally as

additional tool for coffee quality evalua‐ may soaking under water for 24 hours af‐

tion. ter mucilage removal and washing.

Harvesting

Harvesting and Post When the coffee bean is ready for harvest‐

Harvest Handling ing it turns a dark berry color. This will

typically take place between September

and March in the Northern Hemisphere

and between April and May in the Southern

Hemisphere. In some countries where

there is little clear distinction between dry

and wet seasons a major and minor crop

may be able to be harvested annually.

Countries on the equator are able to har‐

vest year round. Harvesting of superior

coffees tends to be done by hand as

mechanized picking can gather over ripe

berries and an acrid taste may affect cup

quality according to the FAO of@ice for Asia

and the Paci@ic. (Alastair Hicks) Of the

Photo of Washing Station Courtesy SPREAD, Rwanda various methods in practice, selective hand

picking best ensures that only fully ripe

beans are taken. However a cost bene@it

Ideal conditions for coffee production such analysis will inevitably be undertaken by

as the agronomic factors of soil nutrition, every coffee grower as to whether the in‐

shading, watering and superior genetics creased level of quality found in picking

will not yield high cup quality without op‐ only the ripest cherries is worth the extra

timal harvesting, processing and storage. expense of undertaking multiple harvests

According to Van Der Vossen, 2009 only in the same season. Clifford, 1985 pro‐

freshly harvested and fully ripe berries poses that Wet processed Arabica tends to

should be used in any of the three methods be aromatic with a @ine acidity but some

of primary processing. Those methods in‐ astringency while dry processed Arabica

clude washed, semi‐dry and dry process‐ tends to be less aromatic but produce

ing. Hand picking coffee beans is the greater body. This is largely due to the

dominant method for accomplishing such formation of acids in under water fermen‐

distinction but there are methods of tation.

mechanized picking that separate the im‐

mature green from the ripe cherry before

processing. Unripened coffee beans tend to Dry Processing

produce astringent, bitter and “off” @la‐

vored beverages. Delays in depulping and Post harvest processes include both dry

prolonged fermentation often lead to onion and wet methods used to process green

@lavor or unpleasant smells . Wet fermen‐ cherry coffees. Dry processing is the sim‐

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 11

Draft Copy

plest and least expensive method of coffee defects are caused by wrong fermentation.

processing. It tends to produce “natural” In fermentation there are primarily two

tasting coffees and is used mostly in West‐ microorganisms at work to shape the even‐

ern Africa and Brazil. Harvested berries tual cup quality, bacteria and yeasts. Dur‐

are sorted and cleaned to remove dirt, ing proper fermentation the bacteria feed

twigs and leaves by hand . Berries are then on sugars of the mucilage. As soon as the

spread out in the sun and raked regularly sugars have been digested and the muci‐

to keep fermentation at bay. In the dry lage has been lique@ied, the pH in the fer‐

method, coffee beans were dried as a mentation tank begins to decrease. It is at

whole with pulp and mucilage in the cherry this point of loweing pH that the yeasts be‐

state. Dry processing is slow and can lead gin to become active. The yeasts go on to

to the translocation of chemical constitu‐ convert sugar to alcohol but are also me‐

ents from the pulp to the inner bean as well tabolizing the solid parts of the mucilage

as chemical transformation that depends resulting in aroma qualities that can have a

on ambient conditions. negative impact on cup quality. This taste /

smell characteristic is sometimes referred

It is noted by Clark, 1985 that naturally, to as “fruity coffee.” When coffee continues

dry, processed coffee has a better body due in this state even longer under reducing

to the fact that the bean was in contact and acidic conditions, the yeast will con‐

with its mucilage through a greater part of vert sugars into acids as opposed to alcohol

the processing phase. resulting in sour tasting coffee. (Tea & Cof‐

fee, November – December, 2005) Rec‐

ommendations for avoidance of fruity and

Wet Processing sour @lavors include washing of beans as

soon as fermentation has @inished, when all

In the wet method coffee beans are pulped, mucilage has been lique@ied. There is no

fruit and skin are removed, or pulped and across the board time frame for develop‐

demucilated, mucilaginous mesocarp is ment of fruity and sour @lavors as tempera‐

removed under fermentation. In the wet ture and altitude play signi@icant roles in

method fermentation occurs in water at those processes. It is noted that in general

controlled temperatures which produce the best way to avoid these cup defects is to

lower levels of undesirable @lavors. For this wash the parchment coffee as soon as fer‐

reason the wet method is often associated mentation has @inished and parchment

with better cup quality. Gonzales‐Rios et feels rough to the touch.

al., 2007 claim that the quality of green and

roasted coffee, measured by aroma, was

better after conventional fermentation Storage

than after mechanical mucilage removal.

Signi@icant defects can also arise as a result

Wet coffee takes up smells and aromas of insuf@icient drying and / or storage con‐

quickly. Oil constitutes a major component ditions as it is the drying process that pre‐

of the coffee bean’s composition and is able pares beans for processing later on as well

to take up and store smells and @lavors be‐ as storage. When beans are insuf@iciently

fore releasing them during roasting greatly or unevenly dried a decrease in cup quality

affecting cup characteristics. According to can occur much more rapidly than with

the tea and coffee trade journal most cup beans that have undergone an ideal drying

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 12

Draft Copy

process. Stirling, 1974 shows a rapid de‐ tion from beans aided by microorganisms.

crease in cup quality level with increasing The aging effect can be minimized by stor‐

storage time from 6 to 18 months given ing parchment and process beans in low

various moisture contents. The decline in temperature, low oxygen and low humidity

cup quality in wet coffee is due to mold and conditions in order to dissuade bacterial,

bacteria as molds and bacteria grow best in yeast and mold activity. Damaged beans

moisture rich environments and cup char‐ tend to be much more subject to agind as

acteristics change as a result of bacteria the oils in the bean are extruding from the

and mould utilization of sugars in the cof‐ bean and provide a good growing ground

fee bean for metabolism. Tea & Coffee rec‐ for mold and bacteria. Molds have the po‐

ommend a bean moisture content of 10 to tential to grow on dry surfaces and extract

12% before packaging and storage. needed moisture from the air in storage

rooms making humidity a key issue in stor‐

One key aspect of coffee storage is bean age facility design, maintenance and repair.

respiration. Every 24 hours an average of One potential mitigation of the aging proc‐

4.4 milligrams of CO2 are produced by 100 ess on coffee beans is to utilize hermeti‐

grams of coffee beans and the 96 calories cally sealed containers or storage silos as

of heat produced by the 4.4 mg of CO2 will opposed to bags. Such units could mini‐

raise the temperature of the beans .25o Cel‐ mize oxygen levels as well as moisture con‐

sius. A high respiration rate, in combina‐ tact metabolic rates of microorganisms and

tion with heat generation, can cause a loss prolonging the amount of time in storage

of weight and dry material in the bean as that would cause minimal affects on cup

well as bean fat decomposition which plays quality. Little information is available

a key role in the aroma of the cup. (Sivetz about the effect of CO2 in such a system on

and Dosrosier, 1979). the cup quality of the coffee stored.

“Stink coffee” can be produced as a result Green beans can produce a “grassy” or

of excessive fermentation from the normal harsh @lavor cause by picking and process‐

microbes that are at work in coffee proc‐ ing immature cherries. Late in the picking

essing. It is recommended that factory season many cherries loose their green

tanks and machinery be cleaned daily to color but do not turn completely red.

ensure that old beans caught in crevices of These unripe cherries will pulp easily but

machinery do not contaminate a later are full of chlorophyll. This is readily seen

batch of coffee. Extreme over‐fermentation in fresh wet washed parchment which

can germinate the coffee seed which dies shows up the color of the silverskin under‐

quickly and leaves a hollow pit in the end neath. One solution is to dun dry the coffee

of the bean. The dead bean then very when weather conditions permit as ultra‐

quickly develops a cheese smelling texture violet light can bleach out the greenness in

which is highly distinctive when the bean is the silverskin. A slight degree of green

broken or cut. A single bean can contami‐ color will often fade over time, making it

nate and spoil an entire batch of perfectly undetectable at the @inal destination, but a

good coffee. (Coffee & Tea, 2005) strong degree of unripeness will facilitate

chemical absorption back into the oil frac‐

Declining of cup quality is inevitable to tion of the @inal product.

some degree during storage. The reason

for this decline, or aging, is surface oxida‐

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 13

Draft Copy

Onion @lavor is another potential result of cive to maintaining low levels of bacterial

faulty post processing. Onion @lavor occurs life, mold, insects and even prevents the

when the ration of soluble sugars to proto‐ formation of a@latoxins as a byproduct of

pectins (contained in the mucilage) be‐ mold development. Temperature and hu‐

comes too low. The primary rapid buildup midity ranges found in the hermetically

of fermentation bacteria is fuelled by the sealed enclosures were also signi@icantly

relatively high level of sugar present within narrower than for control groups of beans

the ripened mucilage. If excessive fresh stored in silos or in bags in a warehouse.

water is used in pre‐washing of cherries Cupping tests were done monthly on a @ive

and during the pulping process, most of point scale and found that after two

these soluble sugars are leached out before months there was a signi@icant change in

normal fermentation takes place. Conse‐ quality in beans stored in sacks and in si‐

quently, the bene@icial soft rot bacteria can los, from 4.0 to 3.8 while cup quality stayed

be overwhelmed later in the fermentation the same for beans stored in the hermetic

process not only by the yeasts but also by enclosure. After a storage of @ive months

bacteria which convert acetic and lactic ac‐ cup quality for sacked coffee and coffee

ids to propionic and butyric acids which stored in a silo had decreased a full point to

cause the onion @lavor. It has been found 3.0 and were described as “Slight old @lavor

that this fault can be minimized by recy‐ perceptible in cup, slight harshness,

cling of pulping water as maintaining a tainted.” The cup quality from beans

high level of sugars and enzymes in the wa‐ stored hermetically was noted as “Very

ter will facilitate normal bacterial action. good @lavor despite being from the previ‐

ous harvest. Slight @loral @lavor.” Cupping

was done by Café Britt’s cupper Carmen

Café Britt of Costa Rica, in conjunction with Lidia Chavarria as well as the cupper for

the Mesoamerican Development Institute, the Costa Rican Consortium, COOCAFE,

is experiencing positive results in the de‐ Jimmy Bonilla.

velopment of a hermetic storage unit. This

unit facilitates long term storage of coffee

in it’s parchment state without the use of Brewed Coffee

pesticides, the degradation of cup quality,

aroma, or appearance for a period of @ive Once coffee is brewed the decline of pH and

months or more. Coffee beans, even when the quality score were correlated at a

properly dried can reabsorb fungus and number of storage temperatures by Rosa et

bacteria encouraging moisture over time al, 1989. Roas’s sensory analysis allowed

from the atmosphere. The storage of green de@inition of a lower limit of pH at which

beans can be even more problematic as coffee’s shelf life ended. Sivetz and Desro‐

they are more susceptible to quality dete‐ sier, 1979 showed that the decline in pH

rioration. Hermetic enclosures manufac‐ comes as s result of the formation of caffei

tured by Grainpro Inc. in Concord, Massa‐ and quinic acids as breakdown products of

chusetts, are being used to store coffee. chlorogenic acid. This process was found

These enclosures use ultra violet light re‐ to accelerate with increasing storage tem‐

sistance PVC to provide an environment perature. Results show that coffee quality

that maintains a very low moisture (hu‐ remains high as long as pH remains high, in

midity), low oxygen, high CO2 environment. the 5.2 range, after brewing and that the

This type of environment is highly condu‐

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 14

Draft Copy

ideal temperature regime for storage is

near freezing at approximately 4oC.

Conclusions

While the data support few conclusive and

universal equations for coffee quality a few

key tradeoffs are evident from literature.

Firstly, that there is a tradeoff in percep‐

tion, if not in fact, between disease resis‐

tance and cup quality. Further study has

the potential to uncover thresholds in pro‐

ductivity and cup quality tradeoffs in this

@ield. Soil nutrition will also be a key area

of focus in the coming years as decreasing

soil quality due to consistent high yield

output will cause further constriction of

the supply chain through decreasing yields.

This is primarily due to the inability of

small land holder farmers to provide the

expensive inputs necessary for consistent

quality harvests. Larger scale inputs could

be facilitated through larger scale farming

techniques but signi@icant tradeoffs exist

due to decreasing quality of coffees picked

and processed mechanically at one time as

opposed to hand picked beans picked at

the height of their maturity. At this point

major tradeoffs exist for storage as well.

Increased storage times have traditionally

meant supply chain stability at the expense

of cup quality. However, technologies are

being developed that could change this

even this paradigm in the near future.

Working in concert with one another as an

industry, there is no limit to our combined

potential for problem solving.

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 15

Draft Copy

References Bosselmann, A. S., Dons, K., Oberthur, T.,

Olsen, C. S., Ræbild, A. &Usma, H. (2009).

Amorim, A. C. L., Hovell, A. M. C., Pinto, A. C., The in@luence of shade trees on coffee qual‐

Eberlin, M. N., Arruda, N. P., Pereira, E. J., ity in small holder coffee agroforestry sys‐

Bizzo, H. R., Catharino, R. R., Morais, Z. B. tems in Southern Colombia. Agriculture,

&Rezende, C. M. (2009). Green and Roasted Ecosystems & Environment 129(1‐3): 253‐

Arabica Coffees Differentiated by Ripeness, 260.

Process and Cup Quality via Electrospray

Ionization Mass Spectrometry Fingerprint‐ Carvahal, J.F., 1959. Mineral nutrition and

ing. Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Soci‐ crop requirements of the coffee crop. Min‐

ety 20(2): 313‐321. isterio de Agriculture y Ganaderia (MAG) –

Servicio Tecnico Interamericanode Coop‐

Anonymus, 1988. Coffee Research Founda‐ eracin Agricola, Technical Bulletin No. 9.

tion Annual Report, 1987/88 San Jose, Costa Rica 1959. 16pp

Avelino, J., Barboza, B., Araya, J. C., Fonseca, Clarke R.J and K.C. and R.Macrae.1988. Cof‐

C., Davrieux, F., Guyot, B. & Cilas, C. (2005). fee: Agronomy.Vol.4.

Effects of slope exposure, altitude and yield

on coffee quality in two altitude terroirs of Clifford, M.N., 1985. Chemical and physical

Costa Rica, Orosi and Santa María de Dota. aspects of green coffee and coffee

Journal of the Science of Food and Agricul‐ products. In: M.N. Clifford and K.C. Willson

ture 85(11): 1869‐1876. (Eds.), Coffee botany,

biochemistry, and production of beans and

Bertrand, B., Vaast, P., Edgardo, A., Etienne, beverage, pp. 305‐374. Croom Helm,

H., Davrieux, F., Charmetant, P. (2006) London

Comparison of bean biochemical composi‐

tion and beverage quality of Arabica hy‐ Clifford, M. N. and K.C. Willson. 1985. Cof‐

brids involving Sudanese ‐Ethiopian ori‐ fee: Botany, Biochemistry and Production

gins with traditional varieties at various of Beans and Beverages. Croom Helm, Lon‐

elevations in Central America. Tree Physi‐ don and Sydney.

ology 26, p. 1239‐1248.

Decazy, F., Avelino, J., Guyot, B., Perriot, J.,

Bertrand, B., Etienne, H., Lashermes, P., Gu‐ Pineda, C. &Cilas, C. (2003). Quality of Dif‐

yot, B. & Davrieux, F. (2005). Can near‐ ferent Honduran Coffees in Relation to Sev‐

infrared re@lectance of green coffee be used eral Environments. Journal of Food Science

to detect introgression in Coffea arabica 68(7): 2356‐2361.

cultivars? Journal of the Science of Food

and Agriculture 85(6): 955‐962. Esteban‐Díez, I., González‐Sáiz, J. M., Sáenz‐

González, C. &Pizarro, C. (2007). Coffee va‐

Bertrand, B., Guyot, B., Anthony, F. &Lash‐ rietal differentiation based on near infra‐

ermes, P. (2003). Impact of the Coffea red spectroscopy. Talanta 71(1): 221‐229.

canephora gene introgression on beverage

quality of <i>C. arabica</i>. TAG Farah, A., Monteiro, MC., Calado, V., Franca,

Theoretical and Applied Genetics 107(3): AS., Trugo, LC. (2006) Correlation between

387‐394.

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 16

Draft Copy

cup quality and chemical attributes of Bra‐ busta beans using infrared spectroscopy.

zilian coffee. Food Chemistry 98 p.373‐380. Food Chemistry 54(3): 321‐326.

Franca, A. S., Mendonça, J. C. F. &Oliveira, S. Knopp, S., Bytof, G. & Selmar, D. (2006). In‐

D. (2005). Composition of green and @luence of processing on the content of

roasted coffees of different cup qualities. sugars in green Arabica coffee beans. Euro‐

LWT ‐ Food Science and Technology 38(7): pean Food Research and Technology

709‐715. 223(2): 195‐201.

Geromel, C., Ferreira, L., Davrieux, F., Guyot, Luderach, P., Vaast, P., Oberthur, T., O’Brien,

B., (2008). Effects of shade on the devel‐ R. (Date Unknown). Geographical Analyses

opment and sugar metabolism of coffee to Explore Interactions between Inherent

fruits, Plant Physiology and Biochemistry Coffee Quality and Production Environ‐

46 p.569‐579. ment.

Grossman, J. M., Sheaffer, C., Wyse, D., Buc‐ Leroy, T., Ribeyre, F., Bertrand, B., Charme‐

ciarelli, B., Vance, C. &Graham, P. H. (2006). tant, P., Dufour, M., Montagnon, C., Marrac‐

An assessment of nodulation and nitrogen cini, P., Pot, D. (2006) Genetics in Coffee

@ixation in inoculated Inga oerstediana, a Quality. Brazilian Journal of Plant Physiol‐

nitrogen‐@ixing tree shading organically ogy, 18:229‐242.

grown coffee in Chiapas, Mexico. Soil Biol‐

ogy and Biochemistry 38(4): 769‐784. Lyon, S., Bezaury, J. A. & Mutersbaugh, T.

(2010). Gender equity in fairtrade‐organic

Hicks, Alastair (2002). Post Harvest Proc‐ coffee producer organizations: Cases from

essing and Quality Assurance for Specialty/ Mesoamerica. Geoforum 41(1): 93‐103.

Organic Coffee Products. FAO Regional Of‐

@ice for Asia and the Paci@ic Malta, MR. (2008). Cup Quality of Tradi‐

tional Crop Coffee Converted to Organic

Joët, T., Laffargue, A., Descroix, F., Doulbeau, System. Bragantia, Campinas, v.67, n.3

S., Bertrand, B., kochko, A. d. & Dussert, S. p.775‐783.

(2010). In@luence of environmental factors,

wet processing and their interactions on Montavon, P., Duruz, E., Rumo, G. &Pratz, G.

the biochemical composition of green Ara‐ (2003). Evolution of Green Coffee Protein

bica coffee beans. Food Chemistry 118(3): Pro@iles with Maturation and Relationship

693‐701. to Coffee Cup Quality. Journal of Agricul‐

tural and Food Chemistry 51(8): 2328‐

Joët, T., Laffargue, A., Salmona, J., Doulbeau, 2334.

S., Descroix, F., Bertrand, B., De Kochko, A.

&Dussert, S. (2009). Metabolic pathways in Posada H., Ferrand M., Davrieux F., Lasher‐

tropical dicotyledonous albuminous seeds: mes P., Bertrand B. 2009. Stability across

Coffea arabica as a case study. New Phy‐ environments of the coffee variety near in‐

tologist 182(1): 146‐162. frared spectral signature. Heredity, 102 (2)

: 113‐119.

Kemsley, E. K., Ruault, S. &Wilson, R. H.

(1995). Discrimination between Coffea Rosa, M. D., Barbanti, D. & Lerici, C. R.

arabica and Coffea canephora variant ro‐ (1990). Changes in coffee brews in relation

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 17

Draft Copy

to storage temperature. Journal of the Sci‐ Youkhana, A. & Idol, T. (2009). Tree prun‐

ence of Food and Agriculture 50(2): 227‐ ing mulch increases soil C and N in a

235. shaded coffee agroecosystem in Hawaii.

Soil Biology and Biochemistry 41(12):

Siddiqi, M.A., 1980. The selection of Ara‐ 2527‐2534.

bica coffee for Fusarium bark disease resis‐

tance in Bvumbwe, Kenya Coffee, 45:55‐59 (2007). Excellence in a cup. Economist

382(8513): 66‐66.

Sivetz M. and N.W. Desrosier. 1979. Coffee

Technology. The AVI Pub.

Com.Westport, Connectricut.

Sivetz. 1972. How acidity affects coffee @la‐

vor. Food Technology Champaign 26, p70‐

77.

Vaast, P., Bertrand, B., Perriot, J. J., Guyot, B.

&Génard, M. (2006). Fruit thinning and

shade improve bean characteristics and

beverage quality of coffee (Coffea arabica

L.) under optimal conditions. Journal of the

Science of Food and Agriculture 86(2):

197‐204.

Vaast, P., Zasoski, R. J. &Bledsoe, C. S.

(1998). Effects of solution pH, temperature,

nitrate/ammonium ratios, and inhibitors

on ammonium and nitrate uptake by Ara‐

bica coffee in short‐term solution culture.

Journal of Plant Nutrition 21(7): 1551 ‐

1564.

Villarreal, D., Laffargue, A., Posada, H., Ber‐

trand, B., Lashermes, P. &Dussert, S. (2009).

Genotypic and Environmental Effects on

Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) Bean Fatty Acid

Pro@ile: Impact on Variety and Origin Che‐

mometric Determination. Journal of Agri‐

cultural and Food Chemistry 57(23):

11321‐11327.

Wintegens, J.N.2004.Coffee: Growing, proc‐

essing, sustainable production, a

guide book for growers, processors, trad‐

ers, and researchers, WILEY‐VCH

Verlag GmbH &Co.KGaA, Weinheium.

Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Review 18

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- 6ef525464066 PDFDocument18 pagini6ef525464066 PDFfanta tasfaye100% (1)

- Trends in Food Science & Technology: Bing Cheng, Agnelo Furtado, Heather E. Smyth, Robert J. HenryDocument11 paginiTrends in Food Science & Technology: Bing Cheng, Agnelo Furtado, Heather E. Smyth, Robert J. HenryTiara ShintaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Correlation Between The Composition of Green Arabica Co Ee Beans and Thesensory Quality of Co Ee BrewsDocument6 paginiCorrelation Between The Composition of Green Arabica Co Ee Beans and Thesensory Quality of Co Ee BrewssallocinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1541-4337 12365 PDFDocument54 pagini1541-4337 12365 PDFfanta tasfayeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factors Affecting Coffee (Coffea Arabica L.) Quality in Ethiopia: A ReviewDocument9 paginiFactors Affecting Coffee (Coffea Arabica L.) Quality in Ethiopia: A ReviewEwentu MotbayenoreÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S030881462300105X MainDocument20 pagini1 s2.0 S030881462300105X MainShimelis KebedeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revisión Fermentacion CaféDocument15 paginiRevisión Fermentacion CaféDaniel HerreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Factors Affecting Coffee Coffea ArabicaDocument7 paginiFactors Affecting Coffee Coffea ArabicaNgô Thị Thu ThủyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foods 11 03146 v2Document15 paginiFoods 11 03146 v2contactÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coffee Berry and Green Bean Chemistry - Opportunities For Improving Cup Quality and Crop CircularityDocument20 paginiCoffee Berry and Green Bean Chemistry - Opportunities For Improving Cup Quality and Crop CircularitysallocinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nondestructive FT-NIR spectroscopy predicts cocoa qualityDocument9 paginiNondestructive FT-NIR spectroscopy predicts cocoa qualityEsdras FerrazÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1910 15545 1 PBDocument10 pagini1910 15545 1 PBNairo Guerrero MarquezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Preparation of Organic Compost Using Waste Tea PowderDocument3 paginiPreparation of Organic Compost Using Waste Tea PowderLawllolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal Kopi KintamaniDocument18 paginiJurnal Kopi KintamaniSayiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kuhol JulianneDocument15 paginiKuhol JuliannejuliannedeguzmansirÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2023genomic Sequencing in Colombian Coffee Fermentation Reveals New Records of Yeast SpeciesDocument10 pagini2023genomic Sequencing in Colombian Coffee Fermentation Reveals New Records of Yeast SpeciesAngels ValenciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coffee - Husk - Compost With Cover Page v2Document7 paginiCoffee - Husk - Compost With Cover Page v2ElaMazlanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quantification of Caffeine Content in Coffee Bean, Pulp and Leaves From Wollega Zones of Ethiopia by High Performance Liquid ChromatographyDocument15 paginiQuantification of Caffeine Content in Coffee Bean, Pulp and Leaves From Wollega Zones of Ethiopia by High Performance Liquid ChromatographyAngels ValenciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effect of Method of Processing Specialty Coffee Beans Natural Washe - 2022 - LDocument8 paginiEffect of Method of Processing Specialty Coffee Beans Natural Washe - 2022 - LWanessa BrazÎncă nu există evaluări

- J Institute Brewing - 2019 - Black - Faba Bean As A Novel Brewing Adjunct Consumer EvaluationDocument5 paginiJ Institute Brewing - 2019 - Black - Faba Bean As A Novel Brewing Adjunct Consumer EvaluationLuis glezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artikel 3 EngDocument8 paginiArtikel 3 EngAndri PratamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- تسميد عضوي + غير عضويDocument9 paginiتسميد عضوي + غير عضويhusameldin khalafÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Bressani Et Al., 2021) Co-Inoculation of Yeasts Starters - A Strategy To Improve Quality of Low Altitude Arabica Coffee PDFDocument9 pagini(Bressani Et Al., 2021) Co-Inoculation of Yeasts Starters - A Strategy To Improve Quality of Low Altitude Arabica Coffee PDFSandra Paola Moreno RÎncă nu există evaluări

- Profiling of Phenolic Compounds Using UPLC MS For Det 2016 Journal of Food CDocument10 paginiProfiling of Phenolic Compounds Using UPLC MS For Det 2016 Journal of Food CArif ShahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Root LenghtDocument16 paginiRoot LenghtwindamarpaungÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10 1016@j Jenvman 2019 06 027Document11 pagini10 1016@j Jenvman 2019 06 027cristiankiperÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effect of Biogas Slurry On Composting Process and Quality of Cattle Manure-Based Compost and VermicompostDocument11 paginiEffect of Biogas Slurry On Composting Process and Quality of Cattle Manure-Based Compost and VermicompostIJAR JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cider Meta 22Document13 paginiCider Meta 22api-676767477Încă nu există evaluări

- Fermentacioncafe 4Document11 paginiFermentacioncafe 4Leonardo Fabio Galindo GutierrezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hughes2014 Article SustainableConversionOfCoffeeADocument19 paginiHughes2014 Article SustainableConversionOfCoffeeALore CJÎncă nu există evaluări

- Derossi 2017Document25 paginiDerossi 2017Garbayu WasesaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Growth Performance of Cabbage with Organic vs Inorganic FertilizerDocument46 paginiGrowth Performance of Cabbage with Organic vs Inorganic FertilizerYasmin100% (4)

- Analysis of Management and Site Factors To Improve The Sustainability ofDocument10 paginiAnalysis of Management and Site Factors To Improve The Sustainability ofJorge ZapataÎncă nu există evaluări

- Penurunan Kadar Asam Dalam Kopi Robusta (Coffea Canephora) Dari Desa Rantebua Kabupaten Toraja Utara Dengan Teknik PemanasanDocument8 paginiPenurunan Kadar Asam Dalam Kopi Robusta (Coffea Canephora) Dari Desa Rantebua Kabupaten Toraja Utara Dengan Teknik PemanasanNabilah RahmadifaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Volatile Profile of Green Coffee Beans From Coffea Arabica L. Plants Grown at Different Altitudes in EthiopiaDocument13 paginiVolatile Profile of Green Coffee Beans From Coffea Arabica L. Plants Grown at Different Altitudes in EthiopiaAnindya ChattopadhyayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Production of A Non-Alcoholic Beverage F PDFDocument4 paginiProduction of A Non-Alcoholic Beverage F PDFVincent TranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal IndoDocument8 paginiJurnal IndoGemasih AkielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rice-Duck Co-Culture Benefits Grain 2-Acetyl-1-Pyrroline Accumulation and Quality and Yield Enhancement of Fragrant RiceDocument12 paginiRice-Duck Co-Culture Benefits Grain 2-Acetyl-1-Pyrroline Accumulation and Quality and Yield Enhancement of Fragrant Ricehali taekookÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cafe-Suelos y Foliar - Diatomaceous Earth As A Source of Silicon and Its Impact On Soil Physical and Chemical Properties, Yield and Quality, Pests and Disease IncidenceDocument18 paginiCafe-Suelos y Foliar - Diatomaceous Earth As A Source of Silicon and Its Impact On Soil Physical and Chemical Properties, Yield and Quality, Pests and Disease Incidenceviviana erazoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review of Research on Coffee Remains as FertilizerDocument9 paginiReview of Research on Coffee Remains as FertilizerGedamu KurabachewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Environmental Factors On Microbiota of Fruits and Soil of Coffea Arabica in Brazil2020Scientific ReportsOpen AccessDocument11 paginiEffects of Environmental Factors On Microbiota of Fruits and Soil of Coffea Arabica in Brazil2020Scientific ReportsOpen AccessLael IsazaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Food Chemistry: Wenjiang Dong, Rongsuo Hu, Zhong Chu, Jianping Zhao, Lehe TanDocument10 paginiFood Chemistry: Wenjiang Dong, Rongsuo Hu, Zhong Chu, Jianping Zhao, Lehe TanMiguel Ángel CanalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Microbial Ecology and Starter Culture Technology in Coffee ProcessingDocument15 paginiMicrobial Ecology and Starter Culture Technology in Coffee ProcessingLael IsazaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CPH As FertilizerDocument3 paginiCPH As Fertilizerklkl mnkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of Coffee Husk Compost For Improving Soil Fertility and Sustainable Coffee Production in Rural Central Highland of VietnamDocument6 paginiEvaluation of Coffee Husk Compost For Improving Soil Fertility and Sustainable Coffee Production in Rural Central Highland of VietnamAV TeoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Variety and Shelf Life of Coffee Packaged in Capsules 2020 LWTDocument9 paginiVariety and Shelf Life of Coffee Packaged in Capsules 2020 LWTElif BağcıvancıoğluÎncă nu există evaluări

- Proximate Analysis of Enhanced Coffea Canephora Var With Endemic Floral SpeciesDocument13 paginiProximate Analysis of Enhanced Coffea Canephora Var With Endemic Floral SpeciesIJELS Research JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aristizabal Coffeequality Ms Draft4Document29 paginiAristizabal Coffeequality Ms Draft4productosbioartesanalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Training On Coffee Quality ImprovementDocument76 paginiTraining On Coffee Quality ImprovementAbenzer MulugetaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tes Home 2019Document12 paginiTes Home 2019hazem alzedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lactuca Sativa L. 28 DicDocument7 paginiLactuca Sativa L. 28 DicYenni Nayid SantamaríaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CoffeeFermentationProcess ReviewDocument16 paginiCoffeeFermentationProcess ReviewJOSÉ EDUARDO A. A. MOURA100% (1)

- Facility-Specific House' Microbiome Ensures The Maintenance of Functional Microbial Communities Into Coffee Beans Fermentation: Implications For Source TrackingDocument12 paginiFacility-Specific House' Microbiome Ensures The Maintenance of Functional Microbial Communities Into Coffee Beans Fermentation: Implications For Source TrackingRuth Noemy Ruiz MangandiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Caffe Fisicoquimica PDFDocument9 paginiCaffe Fisicoquimica PDFYodiOlazaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Organic Brown Sugar and Jaboticaba Pulp Influence On Water Kefir FermentationDocument17 paginiOrganic Brown Sugar and Jaboticaba Pulp Influence On Water Kefir FermentationAngeles SuarezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zhang Et Al., 2019 NewDocument24 paginiZhang Et Al., 2019 NewYon SadisticÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jmbfs 0738 KonfoDocument7 paginiJmbfs 0738 KonfoCamila PinzonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pumpkin Peel Flour (Cucurbita Máxima L.) - Characterization and Technological ApplicabilityDocument8 paginiPumpkin Peel Flour (Cucurbita Máxima L.) - Characterization and Technological ApplicabilityAkash SrivastavÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analisis Mutu Organoleptik Kopi Bubuk Arabika (Coffea Arabica) Bittuang TorajaDocument11 paginiAnalisis Mutu Organoleptik Kopi Bubuk Arabika (Coffea Arabica) Bittuang TorajadewiardianiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prosopis as a Heat Tolerant Nitrogen Fixing Desert Food Legume: Prospects for Economic Development in Arid LandsDe la EverandProsopis as a Heat Tolerant Nitrogen Fixing Desert Food Legume: Prospects for Economic Development in Arid LandsMaria Cecilia PuppoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why High Tech Breeding Is An Urgent Need For High Quality CoffeesDocument8 paginiWhy High Tech Breeding Is An Urgent Need For High Quality CoffeesgcqriÎncă nu există evaluări

- GCQRI Concept PaperDocument26 paginiGCQRI Concept PapergcqriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Could Plant Science Contribute To A Sustainable Growth of Specialty Coffee Industry?Document27 paginiCould Plant Science Contribute To A Sustainable Growth of Specialty Coffee Industry?gcqriÎncă nu există evaluări

- McEachern PresentationDocument3 paginiMcEachern PresentationgcqriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Schilling Quality PresentationDocument16 paginiSchilling Quality PresentationgcqriÎncă nu există evaluări

- General GCQRI Meeting Slides Day 1Document8 paginiGeneral GCQRI Meeting Slides Day 1gcqriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Could Plant Science Contribute To A Sustainable Growth of Specialty Coffee Industry? (II)Document5 paginiCould Plant Science Contribute To A Sustainable Growth of Specialty Coffee Industry? (II)gcqriÎncă nu există evaluări

- General GCQRI Meeting Slides Day 2Document7 paginiGeneral GCQRI Meeting Slides Day 2gcqriÎncă nu există evaluări

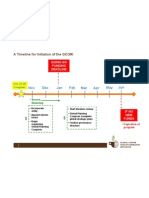

- GCQRI TimelineDocument1 paginăGCQRI TimelinegcqriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dugas PresentationDocument12 paginiDugas PresentationgcqriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative: Carlos Henrique Jorge Brando P&A Marketing International October 2010Document14 paginiGlobal Coffee Quality Research Initiative: Carlos Henrique Jorge Brando P&A Marketing International October 2010gcqriÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Congress AgendaDocument8 paginiThe Global Coffee Quality Research Initiative Congress AgendagcqriÎncă nu există evaluări

- GCQRI - Concept PaperDocument26 paginiGCQRI - Concept Papergcqri100% (1)

- Market Participants in Securities MarketDocument11 paginiMarket Participants in Securities MarketSandra PhilipÎncă nu există evaluări

- 04 Activity 2Document2 pagini04 Activity 2Jhon arvie MalipolÎncă nu există evaluări

- MMDS Indoor/Outdoor Transmitter Manual: Chengdu Tengyue Electronics Co., LTDDocument6 paginiMMDS Indoor/Outdoor Transmitter Manual: Chengdu Tengyue Electronics Co., LTDHenry Jose OlavarrietaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eship 1Document18 paginiEship 1Yash SoniÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument3 paginiUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Syllabus - Mech 3rd YearDocument130 paginiSyllabus - Mech 3rd YearAbhishek AmarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sierra Wireless AirPrimeDocument2 paginiSierra Wireless AirPrimeAminullah -Încă nu există evaluări

- RS-RA-N01-AL User Manual of Photoelectric Total Solar Radiation TransmitterDocument11 paginiRS-RA-N01-AL User Manual of Photoelectric Total Solar Radiation TransmittermohamadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Telangana Budget 2014-2015 Full TextDocument28 paginiTelangana Budget 2014-2015 Full TextRavi Krishna MettaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enhancing reliability of CRA piping welds with PAUTDocument10 paginiEnhancing reliability of CRA piping welds with PAUTMohsin IamÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Punjab Commission On The Status of Women Act 2014 PDFDocument7 paginiThe Punjab Commission On The Status of Women Act 2014 PDFPhdf MultanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gigahertz company background and store locationsDocument1 paginăGigahertz company background and store locationsjay BearÎncă nu există evaluări

- Proprietar Utilizator Nr. Crt. Numar Inmatriculare Functie Utilizator Categorie AutovehiculDocument3 paginiProprietar Utilizator Nr. Crt. Numar Inmatriculare Functie Utilizator Categorie Autovehicultranspol2023Încă nu există evaluări

- Amended ComplaintDocument38 paginiAmended ComplaintDeadspinÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2023 Prospectus 2Document69 pagini2023 Prospectus 2miclau1123Încă nu există evaluări

- WPB Pitch DeckDocument20 paginiWPB Pitch Deckapi-102659575Încă nu există evaluări

- De Thi Thu THPT Quoc Gia Mon Tieng Anh Truong THPT Hai An Hai Phong Nam 2015Document10 paginiDe Thi Thu THPT Quoc Gia Mon Tieng Anh Truong THPT Hai An Hai Phong Nam 2015nguyen ngaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Books 2738 0Document12 paginiBooks 2738 0vinoohmÎncă nu există evaluări

- CCTV8 PDFDocument2 paginiCCTV8 PDFFelix John NuevaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Checklist PBL 2Document3 paginiChecklist PBL 2Hazrina AwangÎncă nu există evaluări

- University Assignment Report CT7098Document16 paginiUniversity Assignment Report CT7098Shakeel ShahidÎncă nu există evaluări

- FOMRHI Quarterly: Ekna Dal CortivoDocument52 paginiFOMRHI Quarterly: Ekna Dal CortivoGaetano PreviteraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Racial and Ethnic Challenges in the UAE vs UKDocument16 paginiRacial and Ethnic Challenges in the UAE vs UKATUL KORIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nuxeo Platform 5.6 UserGuideDocument255 paginiNuxeo Platform 5.6 UserGuidePatrick McCourtÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manual de Instalare Centrala de Incendiu Adresabila 1-4 Bucle Teletek IRIS PRO 250bucla 96 Zone 10000 EvenimenteDocument94 paginiManual de Instalare Centrala de Incendiu Adresabila 1-4 Bucle Teletek IRIS PRO 250bucla 96 Zone 10000 EvenimenteAlexandra DumitruÎncă nu există evaluări

- HandoverDocument2 paginiHandoverKumaresh Shanmuga Sundaram100% (1)

- Part 9. Wireless Communication Towers and Antennas 908.01 Purpose and IntentDocument12 paginiPart 9. Wireless Communication Towers and Antennas 908.01 Purpose and IntentjosethompsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- (EMERSON) Loop CheckingDocument29 pagini(EMERSON) Loop CheckingDavid Chagas80% (5)

- Affordable Care Act Tax - Fact CheckDocument26 paginiAffordable Care Act Tax - Fact CheckNag HammadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- A K A G .: RUN Umar Shok UptaDocument2 paginiA K A G .: RUN Umar Shok UptaArun GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări