Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Dada Berlin: "A History of Performance (1918-1920) "

Încărcat de

Franz JungTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Dada Berlin: "A History of Performance (1918-1920) "

Încărcat de

Franz JungDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Dada Berlin: "A History of Performance (1918-1920)"

Author(s): Mel Gordon

Source: The Drama Review: TDR, Vol. 18, No. 2, Rehearsal Procedures Issue and Berlin Dada

(Jun., 1974), pp. 114-124

Published by: The MIT Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1144908 .

Accessed: 15/12/2014 02:46

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Drama Review:

TDR.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Mon, 15 Dec 2014 02:46:10 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A History of Performance (1918-1920)

Dada Berlin

By Mel Gordon

During recitals of simultaneous poetry

of the most incomprehensible kind, we

attacked the art-loving, Boulevard

public with toy guns, toilet paper, false

beards, and the poetry of Wolfgang

Goethe and Rudolf Presber... Under

the motto "Art is shit!", the Dadas

began their demolition ... (of

bourgeois culture).

Erwin Piscator

In the years 1918, 1919, and 1920, the Berlin Dada movement, mounting less than

thirty productions, exerted a formidable, if indirect, influence over the development

of the German theatre. This influence would later lead to the dismantling of Ex-

pressionism as the dominant theatrical force in Central Europe. Retooling the theories

and performance techniques that they inherited from the Futurists and the Zurich

Dadas to their own specifications, the Berlin Dadas introduced the use of pure-

onomatopoetic or vowel-sound and abstract movement, improvisation,

simultaneous and illogical actions, verbal and physical assault on the spectator, anti-

illusionist scenic design, and the incorporation of popular entertainments, such as

cabaret acts and cinema, into German performance. Together with these novel theat-

rical devices and through direct attacks on Expressionism, the Berlin Dadas laid the

foundations for many of the anti-illusionist movements of the post-World War One

era-Piscator's Epic Theatre, the agitational revues of the German Communist Party

(KPD), Oskar Schlemmer's theatre workshop at the Bauhaus, the Constructivist ex-

periments of El Lissitzky and Frederick Kiesler in Hanover and Vienna, and JirfFrejka's

Devetsil group in Prague.

Unfortunately, the actual records of the Berlin Dada performances remain frag-

mentary and frequently inconsistent, despite a rather lavish coverage accorded them

by the local newspapers. This and the sometimes confused recollections of the Dadas

themselves would account for the paucity-and often inaccuracy-of the secondary

literature. The following material is based on the newspaper records, programs,

memoirs, and Dadaist records of the time.

Six months after the closing of the first Dada theatre, the Cabaret Voltaire in

Zurich, Richard Huelsenbeck returned to Berlin. Although we can only conjecture

what his mental state was at the time-January 1917--it would appear that it was

hardly good. His life-long friend and mentor, Hugo Ball, had terminated all relation-

ship with the Zurich Dadas and the Cabaret Voltaire to live the life of a monk with his

mistress Emmy Hennings in Ticino. Suffering from a "nervous stomach" and insomnia,

Huelsenbeck was unable to leave Zurich for weeks; finally, the news of his father's

declining health brought him back to Berlin.

Virtually every general survey of Dada marks Huelsenbeck's arrival in Berlin in

January 1917 as the beginning of the Dada movement in Berlin, yet for the next thir-

teen months we have no record of any Dada activity or performance; in fact, the word

"Dada," except in reference to the Cabaret Voltaire, is never mentioned. Then, early

in 1918, after a full year in Berlin, Huelsenbeck decided to give a reading. He invited

Title photograph is of Wieland Heartfield,demonstratingthe Dada-Slogan"EveryMan is His

Own Football."

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Mon, 15 Dec 2014 02:46:10 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DADA BERLIN 115

Max Herrmann-Neisse and Theodor Daubler, two Expressionist poets he met at the

Cafe des Westen, and his friend Grosz, whose grotesque paintings were becoming

well-known, to accompany him. The evening was set for J. B. Neumann's Gallery, the

Graphisches Kabinett, on February 18, 1918. Thus, after submitting his work to the

government censors, Huelsenbeck arrived at the Graphisches Kabinett.

The reading took place in a small room on the first floor of the

building. I told Herr Neumann I would give a brief introductory

speech. Which was all right with him. Then, without his or my

friends knowledge, I spoke about Dada. I said the reading was dedi-

cated to Dada.

(Richard Huelsenbeck, Memoirs of a Dada Drummer, forthcoming)

Flourishing his cane, "violent, perhaps arrogant, and unmindful of the conse-

quences," Huelsenbeck proceeded to read what was later published as "The First

Dada-Speech in Germany." As Georges Hugnet pointed out in his The Dada Spirit in

Painting, "Huelsenbeck's lecture ... was much less combative than the German Dada

activities were to become." In fact, the beginning of the speech reads like a youthful,

but modest, travelog of the activities of the Cabaret Voltaire of two years before:

We had to find some common ground between the Russians, Ru-

manians, Swiss, and Germans. There was a witches' sabbat such as

you cannot imagine, a hurrying and scurrying from morning until

evening, an intoxication of drums and tom-toms, an ecstasy of tap

and Cubist dances.

(Richard Huelsenbeck, "First Dada-Speech in Germany," in Dada

Almanach 1920)

Later in the speech, Huelsenbeck denigratingly referred to the Cabaret Voltaire

as an "experimental stage." Only when he began to recite examples of his imitative

African, lautgedichte (sound-poems), the Phantastische Gebete (Fantastic Prayers),

did the audience and gallery owner stir. In fact, Neumann, the proprietor, was already

at the telephone, threatening to call the police. Huelsenbeck's friends immediately

intervened. As a rebuff to Neumann, Huelsenbeck shouted out that the Dadas were in

favor of war and that even the last one was not bloody enough.

Horror! An invalid with a wooden leg got up and the audience rose

to their feet and accompanied his exit with applause ... The

audience not merely rose to their feet but moved toward the ros-

trum in order to hurl themselves at me. But as is usual in such situa-

tions (I went through many like it in my Dada time), public fury was

checked by a kind of awe.

(Huelsenbeck, forthcoming)

At that moment on February 18, 1918, the Berlin Dada movement was launched.

Huelsenbeck continued his speech, which grew more and more vociferous-at-

tacking the Cubists and Futurists, describing the man of the future, the new, brave,

chance-accepting Dada-man. Huelsenbeck concluded with a promise to recite again

from his Phantastische Gebete at the end of the evening. Daubler and Herrman-

Neisse were undecided as to what they should do. But the crowd was demanding that

the readings continue since they wanted to know more about Dada. With much mis-

giving, the two poets walked on the stage and read their compositions.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Mon, 15 Dec 2014 02:46:10 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

116 MEL GORDON

Grosz, who had alreadyworked in cabaret for a number of years, startedto recite

his poetry, which sometimes was little more than rhymed or unrhymed insults-

"You sons-of-bitches, materialists,/bread-eaters, flesh-eaters-vegetarians!!/pro-

fessors, butchers' apprentices, pimps!/-you bums!l" Suddenly Grosz clutched his

groin and began to violently pace back and forth before a recently displayed Ex-

pressionist painting. Then, as Walter Mehring relates, "Cries of 'Shame on you!' ac-

companied the obscene tap-dance of George Grosz, who, pantomimically relieved

himself before Professor Louis Corinth's canvases." Grosz attempted to calm the

ragingaudience with a plea that urine was only a superiorvarnish.

As promised, Huelsenbeck returned to the stage with more Phantastische

Gebete. Although he demanded absolute silence and complete attention, at some

point in his reading, the restless audience began to stand up, either in protest or

confusion. Setting his poems aside, Huelsenbeck lashed out at them, "What are you

really waiting for? The next downfall of Germany?Aren't you satisfied with enough

victims?"The incongruity of Huelsenbeck's nonsense poetry and his appeal to the

audience's patriotic instinctsproduced a deathly silence. Huelsenbeck then, in official

tones, read from an announcement, "Names and orders of the Dada-Central-Com-

mittee: Sit down, Berlin! We declare that everything here in our modern perfor-

mance is shared with our highly-esteemed poet colleagues. And everyone in the

gallery is to be pronounced an honorarymember of Dada!"

Exactly how the audience reacted to Huelsenbeck's seemingly conciliatory

message is not clear. J. B. Neumann maintained in 1950 that the audience completely

wrecked his gallery at the end of the soiree.

Whatever Huelsenbeck's original intentions were-and again judging from the

text, they must have been quite modest-the evening was a fantastic Dada-success.

According to Huelsenbeck:

The next day, the newspapers ran huge headlines, which is unusual

for readings of this kind. Most of the papers were indignant, others

tried to make fun of Dada. A good deal was said about the word

"Dada"; it was called baby talk,jungle noise, parrot chatter. Much

to Daubler's and Herrmann-Neisse's sorrow, a number of critics

earnestly discussed Dada, which forced the two of them to print a

public statement againstit.

(Huelsenbeck, forthcoming)

On April 12, 1918, at the BerlinerSezession, Huelsenbeck with his friends from

the Cafe des Westens-Raoul Hausmann, FranzJung, Gerhard Preiss, and Grosz-

presented the second Dada-soiree. Compared to the February performance,

however, this one was meticulously planned: A large hall a few doors down from the

Graphisches Kabinett on Berlin's main thoroughfare, the Kurfurstendamm,was

rented; detailed announcements were sent to all the papers; and co-signers for

Huelsenbeck's collective manifesto were solicited throughout art circles in Europe.

An off-print of this manifesto, listed in the program as "Dadaism in Life and in Art,"

was distributedto the audience. Forthree Marks,Huelsenbeck offered to sign it.

The evening began with a frenzied attackon Expressionismby Huelsenbeck:

The best and most extraordinaryartistswill be those who every hour

snatch the tatters of their bodies out of the frenzied cataractof life.

... Has Expressionism fulfilled our expectations of such an art,

which should be an expression of our most vital concerns? No! No!

No! Have the Expressionistsfulfilled our expectations of an art that

burns the essence of life into our flesh? No! No! No!...

(Huelsenbeck, Collective Dada Manifesto, 1918)

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Mon, 15 Dec 2014 02:46:10 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DADA BERLIN 117

Against the Expressionist esthetic, Huelsenbeck placed the Dada-art of the

Bruitist (onomatopoetic), Simultaneous (multiple), and Static (vowel) poem, the

Cubist dance, and the Bruitist music of the Futurists. "The word 'Dada' symbolizes the

most primitive relation to the reality of the environment ... Dada is a state of mind

that can be revealed in any conversation ... to be a Dada means to let oneself to be

thrown by things, to oppose all sedimentation ... To be against this manifesto is to be

Dada."

Huelsenbeck concluded by reading the names of the co-signers of the manifesto,

which included Berlin and Zurich Dadas as well as Italian sympathizers-among them

the Futurist Enrico Prampolini. Yet, in spite of the provocative nature of the manifesto

and Huelsenbeck's aggressive delivery, the members of the audience, although tense,

remained relatively calm. Grosz recited his poems in rapid succession. When Else

Hadwiger, who was scheduled to read Futurist and Dadaist poetry, began to read

some of Marinetti's poetry extolling the virtues of war, to which Huelsenbeck pro-

vided a musical accompaniment on a toy trumpet and rattle, the public's attention

was suddenly shifted away from the stage: In the middle of the hall, a soldier in a

field-grey uniform, falling to the floor, was gripped by a fit of epilepsy. The audience

was in a state of panic. Just then, Hausmann embarked upon his lecture, "The New

Materials in Painting," which attempted to analyze man's "sexopsychic capacity" in

art and the exploration in art of real objects. The combined effect must have been too

great for the already pained spectators:

My text, "The New Materials in Painting," created such a commo-

tion that the management, who was worried about its paintings dis-

played on the walls, switched off the lights in the middle of my

speech, condemning me to darkness and silence.

(Raoul Hausmann, Am Anfang War Dada, 1972)

Although the other participants considered the soiree "a splendid evening, a

Dada-success," and were greatly relieved at the uniformly negative press reviews,

Huelsenbeck, for reasons that are still not clearly established, left Berlin that night and

went into hiding in his native city of Brandenburg.

Within a few weeks, the conspicuous Dadas with their childish mock-

revolutionary names* and bizarre theatrical uniforms-Grosz walked the

Kurfurstendamm dressed as Death-were seen everywhere, shouting slo-

gans and pasting up stickers, such as "Dada kicks you in the behind and you

like it," or "What have the gentlemen done with the stage?" Matinees and

soirees for the spring and summer were planned. One such performance,

advertised in the only number of their official organ, Club Dada, an-

nounced, "A propaganda-evening for the end of May," with a "Si-

multaneous Poem (six participants), Bruitist Music, and Cubist Dances (ten

ladies). Orders and inquiries are to be directed to Richard Huelsenbeck,

By June 1918, the Dada manifestations were reduced to a few matinees

at the only pub that would have them, the Cafe Austria. On June 6th, Johan-

*Richard Huelsenbeck: Weltdada, Meisterdada; Raoul Hausmann: Dadasoph;

George Grosz: B6ff, Dadamarshal,Propagandada;Johannes Baader: Oberdada;

John Heartfield: Monteurdada, Mutt; Walter Mehring: Walt Merin, Pupi-Dada;

GerhardPreiss:Music-Dada;Wieland Herzfeld: Vize. Eventhe unofficial members

took Dada-names-Otto Schmalhausen:Dada-Oz, Dr. Otto Burchard:Finanz-Dada,

and H. H. Stuckenschmidt:Music-DadaII.

George Grosz as the Dada-Death.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Mon, 15 Dec 2014 02:46:10 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

118 MELGORDON

nes Baader,who had already been certified as legally insane by the BerlinPolice De-

partment, performed with Hausmann. Although there are no extant newspaper re-

views, it is unlikely that these matinees were more than readings of lautgedichte and

exchanges of insultswith some beer-guzzling onlookers amidstdisplaysof Dadaistart,

namely abstract drawings and photo-montage, which the Berlin Dadas credit

themselves as originating.

The next recorded Dada performance did not occur until February1919. That

matinee is largely remembered for the mounting antagonism it reflected between

Huelsenbeck and the rest of the Dadas. Clearly, much of the tension was due to the

growing political struggle within the Dada movement. Although the Berlin Dadas

were vehemently opposed to the bourgeois Social Democratic regime of Philipp

Scheidemann and FriedrichEbert,who seized power in November 1918,to forestall a

Communist revolution after the abdication of the Kaiser,their personal support of the

Spartakists (the Communist opposition) ranged from active participation (Grosz,

Heartfield, Herzfeld) to utter ambivalence (Huelsenbeck). In the Januaryand March

reactions, following the abortive Spartakistinsurrection of Rosa Luxenburgand Karl

Liebknecktin December 1918, several of the BerlinDadaswere taken into "protective

custody" and threatened with death by the proto-Nazi Freikorps.Only the interven-

tion of influential intellectuals, like Count HarryKessler,was thought to have saved

their lives.

At the end of April1919,the Dadas felt safe enough to mount an art exhibition of

their newest works.Joined by the newly arrivedRussian,EfimGolyschef, Hausmann,

in Huelsenbeck's absence, returned to one of the old Dada haunts, Neumann's

Graphisches Kabinett. Golyschef, who remained in the Dada movement only a few

months, brought with him many of the ideas of the Russian Futuristmovement he

picked up during the war. An accomplished painter and musician at twenty-two,

Golyschef had developed an atonal twelve-tone scale based on the principles of the

"duration complex" in 1914, independently of Arnold Sch6nberg. To mark the

closing of the Dada art display, which Hausmann claims included the first Assem-

blages-"compositions realized in eccentric materialssuch as jelly boxes, glass, hair,

paper lace"-an elaborate programwas planned for the evening of April30th.

After calling for silence, Hausmannread his newest lautgedichte, the Seelen-Au-

tomobil (Automobile Souls), thundering "with a high and mighty voice BOUMM DE

DE." Heartfield and Grosz performed, and Golyschef played his notorious Antisym-

phony. Hausmannlater recounted:

Golyschef entered with a young woman dressed in white. I can still

see this scene today as if nothing had changed. Witha feeble smile,

Golyschef turned toward the grand piano and, makinga tiny gesture

of an innocent, white angel with his hand, sat down. He said in the

voice of an electronic puppet: "Aperformance of

The Antisymphonyin Three Parts(The CircularGuillotine).

a) The ProvocativeInjection.

b) The Chaotic Oral Cavity.

c) The PliableSuper-FA.

Well, well, Herr Johann Sebastian Bach, your well-tempered trash

will experience the clashing of the dodecahedral Antisymphony!

Out and away with the fine pedantries of the, ach so splendid, es-

tablished-traditions!Dada will triumph in sound as well! Ladiesand

gentlemen, do your rust-encrusted ears resound? Then, let the

musical circular-saw cut them right through! Douche away the

dregs of your voice from the chaotic oral cavities with Golyschef!"

(Hausmann,1972)

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Mon, 15 Dec 2014 02:46:10 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Then with the assistance of a kitchen-utensil playing orchestra and an imitation

Dalcroze dancer, Golyschef performed his atonal Antisymphony.

Despite Hausmann'sprivate misgivingsover the favorable critical reactions, the

April 30th soiree received, a second, even more grandiose, production was planned

for May 15th at the large Meister-Hall on the Kurfurstendamm.(For a complete

description, see page 125).At this time, Dadaismin Berlinwas at the height of its noto-

riety;young artists,designers, songwriters,musicians,writers,and performersfrom all

over Germany and Central Europestreamed into Berlinto experience the Dada-Re-

bellion first hand-and perhaps to be formally invited into the exclusive Club Dada.

Under the rallying-cry"Dada-Osirisis the answer to death," Alfred Sauermannpre-

sented his own imitative Dada-playsat the Theatre of the Club of the Grotesque: "I

appear before you like the God Phallus.(He, too, had a small head and a long neck.)

Perhaps, he was also an undefeated racehorse. Gentlemen, shall we bet on that?"

Treatisesby famous criticspraisingor denigrating Dadaismappeared in the shuttersof

neighborhood kiosks throughout Berlin. Everynewspaper felt obligated to present

their own theory about the social and esthetic meritsof Dadaism.

At the Dada-matinees and Dada-soirees given at the Meister-Hall,a number of

established acts unfolded: Grosz' and Mehring's Contest Between the Sewing Ma-

chine and Typewriter(See page 130) and their PrivateConversation of Two Senile

Men Behind a Firescreen;GerhardPreiss'Dada-Trott;Hausmann'srecitation of the

Seelen-Automobil and his "sixty-one-step" dance, which he sometimes performed

when the audience became unruly;and, of course, Huelsenbeck's perennial reading

of the Phantastische Gebete. More than twenty years later in America, Grosz

described the natureof these performances:

We held meetings and charged a few Marksadmission but gave in

returnno more than truisms... Our mannerswere downright arro-

gant. We would say, "Youheap of dung down there, yes, you, with

the umbrella, you simple fool." Or, "Hey, you on the right, don't

laugh, you ox." If they answered us, as they naturallydid, we would

say as they do in the army:"Shutyour trapor you'll get kicked in the

butt."

(Grosz,A LittleYesand a Big No, 1946)

Sometimes I'd slap them with my glove and sometimes I'd say, "You

reek with corruption, and now five hundred Marks,please." Later

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Mon, 15 Dec 2014 02:46:10 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

120 MELGORDON

the police had to protect us. I was sometimes very witty. "Shut up!"

I'd say, "You kept your mouths shut for four years. Now keep them

shut a little while longer." Sometimes we had hand-to-hand

fighting.

(Grosz, in The New Yorker, 1943)

When we weren't swearing at the public, we were indulging in so-

called "art." That is, we deliberately staged our "artistic" acts. For

instance, Walter Mehring would pound away at his typewriter,

reading aloud the poem he was composing, and Heartfield or

Hausmann or I would come from the backstage and shout: "Stop,

you aren't going to hand out real art to those dumbbells, are you?"

Sometimes these skits were prepared, but by and large they were

improvised. Since we usually did a bit of drinking beforehand, we

were always belligerent. The battles that started behind the scenes

were merely continued in public, that was all. This was startlingly

novel to the people, consequently we were hugely successful. Fads

like ours generally lasted only a few months.

(Grosz, 1946)

Although Dada had clearly caught the public's eye, by June, Baader, Hausmann

and Huelsenbeck switched to literary activities-the publication of their journal Der

Dada, a rag-tag of jumbled woodcuts, drawings, manifestos, lautgedichte, Dada-slo-

gans, photo-montage, faked photographs, and reportage. In the manifesto that ap-

peared in the first issue, "What is Dadaism and What Does It Want in Germany,"

Hausmann and Huelsenbeck called for the establishment of simultaneous poetry "as

the Communist state prayer," "the requisition of churches for the performances of

Bruitism, Simultaneist and Dadaist poems," as well as the organization of 150 circuses

in conjunction with a Dadaist propaganda campaign for the "enlightenment of the

proletariat." Later the Dadas would include in their publications dramatic sketches

that would prefigure the Theatre of the Absurd.

In November 1919, two esthetically-opposed theatres inexplicably opened their

doors to the Dadas. In the basement of Max Reinhardt's newly built Grosse Schau-

spielhaus, Ernst Stern, Reinhardt's chief designer, constructed a space for a cabaret.

Based on Reinhardt's successful, pre-war literary cabaret, the Schall und Rauch (Noise

and Smoke), this second Schall und Rauch soon attracted the attention of

Mehring,

who stood outside its doors and harangued the customers in the name of Dada.

Reinhardt, who happened to arrive at that time, immediately commissioned Mehring

to write a song for the next performance in a week's time. One of the refrains

Mehring submitted to Reinhardt, "There's something about love and something

about Noske (in this chanson)" was unexpectedly well received and soon became one

of the most popularly sung refrains throughout Berlin. (Gustav Noske was the much

maligned Minister of Defense. Although a Socialist, Noske armed the right-wing

Freikorps, who through assassination and terror destroyed the Spartakus infrastruc-

ture.) On November 11th, Mehring was invited back to conduct an entire evening.

Together with his friends from the literary and intellectual establishment who were

sympathetic to Dadaism-Kurt Tucholsky, Klabund, and Joachim Ringelnatz-

Mehring presented his Conference provocative. Harping on the Schall und Rauch's

previous function-it was used to house circus animals for the Zircus Schumann-

Mehring, in the best Dada fashion, castigated all of man's entertainments and higher

enterprises as beastial.

The second theatre that invited the Dadas to perform was the leftist Tribune. An

impressionistic account of one of the Dadas' November productions at the Tribbne

appeared in the newspaper"Vorwarts."

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Mon, 15 Dec 2014 02:46:10 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DADA BERLIN 121

A patch-work of questions, sounds, words, and gaudy spectacle.

Masterfulstaging from the first roll of a drum forced the audience

into submission . . . After outlining the evening's program, the MC

began the fireworks: "The worse the world, the better our jokes!"

This sentence lays bare the entire Dada-activity.For the bourgeois

culture has overshot its mark.Itsbrittle wheels have skipped off, and

the wagon is overturning . . . The MC proclaimed, "We are not an

art movement, we are a pure movement, movement incarnate ...

Dada is the returnto primitiveinstincts."

The remainder of the review records a recitation of Hausmann's Seelen-Au-

tomobil, a mock Biblicalskit with the frequent backstagecommands, "You shall have

no other Noske beside him!" and an obscene lecture entitled, "ClassicalReferences

to Middle-ClassCookery."

The next matinee at the Tribune on December 7, 1919, is historicallyimportant

due to Piscator'sparticipation.Beginning with the cry, "Don't startthe show until the

money's in the safe!" Piscator created what was later called the first living photo-

montage with one of Huelsenbeck's sketches. In 1928 Grosz wrote, "Do you re-

member, Erwin, how, long before the Russians, you directed the famous Dada

matinee from the top of a tall ladder,while behind you someone howled long-drawn-

out, coarse speeches from the wings into the audience?"

The next week on the 13th, the Dadas decided to virtually repeat the same

program. At this performance, Mehring wanted to include some of Goethe's poetry.

Without announcing the author, Mehring began to recite the "Wanderer's Storm

Song," while the audience roared at what they assumed was another example of Da-

daist nonsense poetry. Butthe Dadasthemselves knew better.

The entire horde of Dadas, running up to the lip of the stage,

shouted, "Stop!" "Enough twaddle!" they boomed. "Walt!" Boff

growled with a fixed monocle, "Walt, you are only throwing...

pearls ... before these pigs!" "Stop!" the Dada-choir roared in

unison. "Get out! Ladiesand gentlemen, we ask you politely: Go to

Hell! If you wish to amuse yourselves, then go to a whorehouse-or

(Huelsenbeck) to a Momas Thann lecture!" And linking arms, the

Dada-choirdescended from the podium to do battle with the raging

spectators.

(Walter Mehring, Dada Berlin, 1959)

Between these two December matinees at the Tribune, the Berlin Dadas

mounted another production in connection with the Schall und Rauch. Advertised as

an evening of "dancing, recitations,sketches, cartoons, and a political puppet show,"

Rudolf Kurtzand Heinz Herald,the director and dramaturgof the Schall und Rauch,

hoped that a combination of high-quality cabaret entertainment and fashionable-

Dada-political satirewould generate an immense amount of publicity.

In the first partof the evening, Gustavvon Wangenheim read his poetry, "Pierrot

Songs," Lala Hedermenger danced to the music of Robert Forster-Larrinaga,and

Klabundread some of his grotesque stories. Then, an animated film cartoon, drawn in

thick satiricallines by WalterTrier,was projected. Accompanied by the cabaret tunes

of Friederich Hollaender, the composer of many of Marlene Dietrich's Berlin songs,

the film depicted "a day in the life of the Reich's President" Ebert.During the next

act, a familiarsentimental favorite, a "Prince-and-Councilor"sketch, Mehring started

a disturbance. In the awkwardsilence that followed the outburst, Gertaud Eysoldtde-

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Mon, 15 Dec 2014 02:46:10 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A George Groszsketch

of the marionettes

from Simply Classical!

livered her comic speeches. She was followed by Paul Graetz and Blandine

Hollaender, two of the most popular cabaret singers in Berlin. Then came the

promised highlight of the evening, Mehring's political puppet play, "Simply

Classical-An Orestia with a Happy Ending."

Using two-foot marionettes designed by Grosz and executed by Heartfield and

Waldemar Hecker, the Mehring play both satirized the economic, political, and

military events that led to the founding of the year-old Weimar Republic; and

Reinhardt's 1919 production of the Orestia, which was then playing at the Grosses

Schauspielhaus-("Aeschylus above, Aristophanes below" wrote a critic for the

Vossische Zeitung.). It was more concerned with current politics than any re-working

of classical mythology. Except for a few Attic props, the marionettes were dressed in

contemporary costume and given the facial and body characteristics of Grosz'

Weimar types. Judging from the descriptions of the characters in the play, Grosz'

vision could not have been very different from Mehring's: Agamemnon/in the uni-

form of a Junker, "a commanding general in his best years"; Clytemnestra/in the

dress of a cabaret performer, "in her change in life"; Aegisthus/Ebert, "a democratic

president"; Orestes, "an officer in the Attic Freikorps"; a Bourgeois Gentlemen;

Electra, "who becomes transformed into a Salvation Army girl"; a Watchman; and

"Nature Boy."

Divided into three parts, the War, "The Dawn of Democracy," and "The Classical

Absconding of Funds"-the last about the Kaiser's flight to Holland-the puppet play

contained many technical and thematic innovations that would later appear as stock

devices in the theatres of Piscator and Brecht. An alienating Gramophone/Greek

chorus interrupted the action of the play with political songs like "The Oratory of

War, Peace, and Inflation." There were anti-military and anti-American themes-

Electra as a Salvation Army worker. Film was incorporated in the staging-a movie

entitled "Henny Pythia," parodied the film star, Henny Porten: "I am the Duse/

Without the Geschmuse (sugar-coating)."

The evening ended with the Dadas, who were genuinely displeased with Kurtz'

direction, attacking the spectators, among whom was Reinhardt. Huelsenbeck

screamed himself hoarse. "Down with Reinhardtism!" The numerous newspaper

critics wrote about the poor acoustics and faulty ventilation.

The final Dada performances were given by Huelsenbeck, Hausmann, and Baader

on their Dadatour of Dresden (See page 128), Leipzig (February 24, 1920), Teplice-

Schonau in Czechoslovakia (February 26), Prague (March 1 and 2), and Karlsbad

(March 5). Largely due to an effective public relations campaign of promoters, local

Dadas, and copy-hungry newspapers, the Berlin Dada performances attracted

enormous and unwieldly crowds. In Leipzig, when a policeman mounted the stage in

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Mon, 15 Dec 2014 02:46:10 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DADA BERLIN 123

order to calm the more than two thousand spectators, he was mistaken for a Dada and

showered with torrents of rotten eggs and potatoes. Huelsenbeck gives us an in-

teresting description of these performances:

To sum up our reading circuit in a single sentence: we annoyed and

bewildered our audiences. The one thing in common to all of our

performances was that we never knew in advance what we were

going to say. I usually read the Phantastische Gebete and

Hausmann,as far as I can remember alwayshad his sound poems on

hand. Butthis materialnaturallycouldn't fill out an evening. So from

the very start,we had to make the audience realize that it shouldn't

expect very much ... Before the performance, I would step over to

the edge of the podium and call out: "Ladiesand gentlemen ... if

you think that we have come here to sing or recite something, then

you are the victimsof an unfortunateerror. It would have been bet-

ter had you gone to the nearest motion picture theatre instead..."

People called out that they wanted to see Dada. "Dadais nothing," I

said. "We ourselves don't know what Dada is..." Someone would

call out "get the police." "Ladiesand gentlemen," I said, "not even

the police can change the fact that we do not intend to offer you

any entertainment such as you generally get in the movies or in the

theatre."

(Huelsenbeck, forthcoming)

Curiously the programs distributed on the Dadatour make the Dadas' perfor-

mances appear slightly more literary and organized than either the Dadas themselves

or the newspaper reviews record. For instance, the program issued for the March 1st

performance at the Produce Exchange in Prague reads:

1. Huelsenbeck: Introduction.

2. Hausmann/Baader:Simultaneouslectures on the knife.

3. Hausmann:Foxty-one-step(Dada-trott).

4. Baader:"My LastFuneral."

5. Huelsenbeck/Baader/Hausmann:Simultaneouspoems.

6. Hausmann:"ClassicalReferencesto Middle-ClassCookery."

7. Huelsenbeck:"PhantischesGebete."

8. Huelsenbeck/Baader/Hausmann:"The Pig Bladderas Anchor."

9. BruitistFinalPromenade.

RichardHuelsenbeck and Raoul Haus-

mann on their Dadatourin Prague.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Mon, 15 Dec 2014 02:46:10 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

124 MELGORDON

Yet, even in this performance, chance, which played such an important part in

the Berlin Dada activities,would determine the nature and organization of the con-

cert: Baader,at the last minute, had fled Prague,taking half the performance scripts

with him.

At the last official Dada gathering in Berlin,the FirstInternationalDada-Messe at

the BurchardGalleryin June 1920,the Berlin Dadas exhibited Dada art from all over

the world, includingtheir own photo-montage and puppets, some of which they used

in their productions. However, we have no records of any performance during the

exhibition.

By the end of 1920, the Berlin Dadas had gone their separate ways. Grosz and

Heartfieldbegan to work in proletariantheatre with HermannSchuller and Piscator.

Hausmannjoined the Hanover Dada, KurtSchwitters(who had been rejected by the

Berlin Dadas in 1918)to perform Merz/Antidada soirees in many of the same places

he had taken the Dadatour. Mehring returned to the Berlin literarycabaret, whose

style and content the Dadashad alreadytransformed.

Hannah Hoch at the First

International Dada-Messe.

SELECTED

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Boyer, RichardO. "Profiles,Artist."in The New Yorker:Nov. 27, 1943; Dec. 4, 1943; Dec. 11,

1943.

Budzinski,Klaus.Die Muse mitScharferZunge. Munich, 1961.

Deshong III, A.W. Theatrical Designs of George Grosz. (unpublished dissertation, Yale

University,1972).

Grossman,Manuel L.Dada: Paradox,Mystification,and Ambiguityin EuropeanLiterature.New

York,1971.

Grosz,George. A LittleYesand a BigNo. New York,1946.

Hausmann,Raoul.CourrierDada. Paris,1958.

Hausmann,Raoul.Am AnfangWarDada.Steinbach/Giessen,1970.

Hosch,Rudolf.Kabarettvon Gestern.Berlin,1967.

Huelsenbeck,Richard.Memoirsof a Dada Drummer.New York,forthcoming.(VikingPress).

Hulsenbeck,Richard,editor. DadaAlmanach.New York,1966(second edition).

Jaguer,Edouard.Golyschef.Milan,1970.

Lewis,Beth Irwin.George Crosz: Artand Politicsin the WeimarRepublic. Madison, Wisconsin,

1970.

Lippard,LucyR.,editor. DadasOn Art. EnglewoodCliffs,N.J.,1971.

Mehring,Walter.BerlinDada. Zurich,1959.

Motherwell,Robert,editor. TheDadaPaintersand Poets. New York,1951.

Richter,Hans.Dada:Artand Anti-Art.New York-Toronto,1965.

The author would like to thankJohn Houchin, IngaKohwaian,JamesF. Brown,Peter Grosz,and

WalterMehringfor their assistance.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Mon, 15 Dec 2014 02:46:10 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Reimagining Time in School For All StudentsDocument24 paginiReimagining Time in School For All StudentsRahul ShahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anna Therese Johanna Höch Nov. 1 1889-May 31 1978: ST STDocument10 paginiAnna Therese Johanna Höch Nov. 1 1889-May 31 1978: ST STbecca_wlfÎncă nu există evaluări

- SJG - DAE - Questioning Design - Preview PDFDocument25 paginiSJG - DAE - Questioning Design - Preview PDFJulián JaramilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Barbara Cruikshank) The Will To Empower (B-Ok - Xyz) PDFDocument157 pagini(Barbara Cruikshank) The Will To Empower (B-Ok - Xyz) PDFDeep Narayan Chatterjee100% (1)

- Pour MIDocument38 paginiPour MINemanja EgerićÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Music of Henry CowellDocument27 paginiThe Music of Henry CowellPablo AlonsoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Against The Current. The Story of The Surrealist Group of Czechoslovakia - Lenka Byd OvskaDocument10 paginiAgainst The Current. The Story of The Surrealist Group of Czechoslovakia - Lenka Byd OvskaSarah Andrews McNeilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Helena Paderewska: Memoirs, 1910–1920De la EverandHelena Paderewska: Memoirs, 1910–1920Încă nu există evaluări

- Ech 404 - Edtpa Task 2Document4 paginiEch 404 - Edtpa Task 2api-505045212Încă nu există evaluări

- PATHFIT 4 Module 1Document11 paginiPATHFIT 4 Module 1Joyce Anne Sobremonte100% (1)

- Music 5 - Unit 1Document4 paginiMusic 5 - Unit 1api-279660056Încă nu există evaluări

- Stillitoe PaulDocument20 paginiStillitoe PaulFacundoPMÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dada 1Document39 paginiDada 1Mimi2007100% (1)

- Käthe Kollwitz: Julia E. Benson ARTS 1610 100 December 12, 2000Document17 paginiKäthe Kollwitz: Julia E. Benson ARTS 1610 100 December 12, 2000Daniel FrancoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Semblance of Things - Corporeal Gesture in Viennese ExpressionDocument322 paginiThe Semblance of Things - Corporeal Gesture in Viennese ExpressiononceuponatimeinromaniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Willem PijperDocument21 paginiWillem Pijpergroovy13Încă nu există evaluări

- John Cage's "The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs": Lauriejean ReinhardtDocument8 paginiJohn Cage's "The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs": Lauriejean ReinhardtMoxi BeideneglÎncă nu există evaluări

- HH Arnason - Expressionism in Germany (Ch. 08)Document22 paginiHH Arnason - Expressionism in Germany (Ch. 08)KraftfeldÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Second Viennese School SchoenbergDocument6 paginiThe Second Viennese School SchoenbergjaredhendersonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modern Dance in Germany and The United States Crosscurrents and Influences (Isa Partsch-Bergsohn)Document421 paginiModern Dance in Germany and The United States Crosscurrents and Influences (Isa Partsch-Bergsohn)Anamaria Tamayo-DuqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rolf de Maré and Ballets SuédoisDocument5 paginiRolf de Maré and Ballets SuédoisolocesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stravinsky Sacre 3Document2 paginiStravinsky Sacre 3Rocco CataniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Finley Drake Program 4.25.18 PDFDocument40 paginiFinley Drake Program 4.25.18 PDFAnonymous mHXywXÎncă nu există evaluări

- Berg - LulúDocument12 paginiBerg - LulúlucasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vienna 1900 Klimt and Gender PoliticsDocument27 paginiVienna 1900 Klimt and Gender Politicsbebi_boo21Încă nu există evaluări

- HH Arnason Cubism CH 10 PDFDocument38 paginiHH Arnason Cubism CH 10 PDFAleksandra ButorovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Powerpoint Oliveros and MonkDocument10 paginiPowerpoint Oliveros and MonkChristian CareyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Balkan Art Scene Vol 1 Issue 1Document59 paginiBalkan Art Scene Vol 1 Issue 1Hana100% (1)

- Artist Case Study - Edvard MunchDocument4 paginiArtist Case Study - Edvard MunchPershernÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alban Berg's Sieben Frühe LiederDocument6 paginiAlban Berg's Sieben Frühe LiederskiprydooÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effect of Wagner On HitlerDocument14 paginiEffect of Wagner On HitlerCamble ScottÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mahler and Klimt Social Experience and Artistic EvolutionDocument23 paginiMahler and Klimt Social Experience and Artistic EvolutionMarthaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wolfgang MozartDocument7 paginiWolfgang MozartNiraj Shrestha100% (5)

- By Deanna R. Hoying Director of Education Kentucky OperaDocument5 paginiBy Deanna R. Hoying Director of Education Kentucky OperaDannySemaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brahms Alto RhapsodyDocument6 paginiBrahms Alto RhapsodyAine Mulvey100% (1)

- Gurrelieder 1Document1 paginăGurrelieder 1fiesta2Încă nu există evaluări

- Henry Purcell Music and LettersDocument8 paginiHenry Purcell Music and LettersDaniel SananikoneÎncă nu există evaluări

- K366 Idomeneo For PDFDocument63 paginiK366 Idomeneo For PDFGerard Pablo0% (1)

- Figures of Authority, Ciphers of Regression: Notes On The Return of Representation in European PaintingDocument31 paginiFigures of Authority, Ciphers of Regression: Notes On The Return of Representation in European PaintingWagner Costa LimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rousseau - MelodyDocument66 paginiRousseau - MelodyIgor ReinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- L' Histoire Du Soldat Historical BackgroundDocument4 paginiL' Histoire Du Soldat Historical BackgroundedfarmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Savage Parade PDFDocument16 paginiSavage Parade PDFJessicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Ocular Harpsichord of Louis-Bertrand Castel: The Science and Aesthetics of An Eighteenth-Century Cause CélèbreDocument63 paginiThe Ocular Harpsichord of Louis-Bertrand Castel: The Science and Aesthetics of An Eighteenth-Century Cause CélèbretheatreoftheblindÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art and MusicDocument92 paginiArt and MusicKiên KiênÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jean (Hans) ArpDocument2 paginiJean (Hans) ArpJoshua Callahan100% (1)

- NeoRomanticism (Grove Online)Document3 paginiNeoRomanticism (Grove Online)EricÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Is Wagner Worth Saving?Document13 paginiWhy Is Wagner Worth Saving?SlovenianStudyReferences100% (63)

- Musician: Arrigo Boito, Librettist andDocument371 paginiMusician: Arrigo Boito, Librettist andOctávio AugustoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bartok - Gypsy Music or Hungarian MusicDocument19 paginiBartok - Gypsy Music or Hungarian MusicRoger J.Încă nu există evaluări

- UP Program NotesDocument3 paginiUP Program NotesLIKOÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of TangoDocument11 paginiHistory of TangovmfounarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Christopher Wilson - Music in Shakespeare A DictionaryDocument499 paginiChristopher Wilson - Music in Shakespeare A Dictionaryluis campins100% (1)

- BellRinging theSacredLiturgicalMusicOfTheChurchDocument3 paginiBellRinging theSacredLiturgicalMusicOfTheChurchMark GalperinÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Writers, Artists, Singers, and Musicians of the National Hungarian Jewish Cultural Association (OMIKE), 1939–1944De la EverandThe Writers, Artists, Singers, and Musicians of the National Hungarian Jewish Cultural Association (OMIKE), 1939–1944Frederick BondyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Musical Composers HungaryDocument46 paginiMusical Composers HungaryIvan Paul CandoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chromaticism and Diatonicism in Beethoven's Waldstein SonataDocument9 paginiChromaticism and Diatonicism in Beethoven's Waldstein SonataLara PoeÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Bach Cult in Late-Eighteenth CenturyDocument6 paginiA Bach Cult in Late-Eighteenth CenturyOmar Valenzuela100% (1)

- Strauss' Salome - Tasteless?Document7 paginiStrauss' Salome - Tasteless?Kai WikeleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modern Drama PDFDocument12 paginiModern Drama PDFMilica StankovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Giacomo Puccini TodayDocument14 paginiGiacomo Puccini Today505272 505272100% (1)

- The French Revolution's Effects On MusicDocument2 paginiThe French Revolution's Effects On MusicKai Roberts100% (2)

- Diaghilev - Cunningham 1974Document7 paginiDiaghilev - Cunningham 1974SquawÎncă nu există evaluări

- Erik Satie Biography PDFDocument2 paginiErik Satie Biography PDFBobby0% (1)

- LOCKSPEISER - The Berlioz-Strauss Treatise On InstrumentationDocument9 paginiLOCKSPEISER - The Berlioz-Strauss Treatise On InstrumentationtbiancolinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cage - Pataphysics Magazine Interview With John CageDocument3 paginiCage - Pataphysics Magazine Interview With John Cageiraigne100% (1)

- 80 1 Larson3Document9 pagini80 1 Larson3syed muffassirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Podcast Plan Template-1Document4 paginiPodcast Plan Template-1api-490251684Încă nu există evaluări

- GCE Units Grade BoundariesDocument13 paginiGCE Units Grade Boundariesredrose_17Încă nu există evaluări

- Brian Farrell CVDocument1 paginăBrian Farrell CVbfarrell11Încă nu există evaluări

- Bric Brazil Works CitedDocument3 paginiBric Brazil Works Citedjjames972Încă nu există evaluări

- Table-Of-Specification Grade 7 (Prelim 3RD)Document1 paginăTable-Of-Specification Grade 7 (Prelim 3RD)KenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lacan and His Influence: Kevin JonesDocument2 paginiLacan and His Influence: Kevin JonesannaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Feminism and Its Importance in Present DaysDocument20 paginiFeminism and Its Importance in Present DaysSpandan GhoshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Joseph W. Dubin The Green StarDocument296 paginiJoseph W. Dubin The Green StarNancy NickiesÎncă nu există evaluări

- N.T. Whright Pablo y La Fidelidad de Dios Tabla de ContenidosDocument5 paginiN.T. Whright Pablo y La Fidelidad de Dios Tabla de ContenidosnoquierodarinforÎncă nu există evaluări

- CV Kashif AliDocument2 paginiCV Kashif AliRao KashifÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Concept of Παπάδειγμα in Plato's Theory of Forms - William J. Prior PDFDocument10 paginiThe Concept of Παπάδειγμα in Plato's Theory of Forms - William J. Prior PDFPricopi VictorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group 2Document19 paginiGroup 2Marjorie O. MalinaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alexis M Stapp ResumeDocument1 paginăAlexis M Stapp Resumeastapp8375Încă nu există evaluări

- Name: Noor-Ul-Dhuha Assignment: First Registration: Sp19-Baf-018 Date: 20-04-2020 Subject: MarketingDocument9 paginiName: Noor-Ul-Dhuha Assignment: First Registration: Sp19-Baf-018 Date: 20-04-2020 Subject: MarketingTiny HumanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Caps SP Mathematics GR 7-9 PDFDocument164 paginiCaps SP Mathematics GR 7-9 PDFthanesh singhÎncă nu există evaluări

- ITK Arctic Policy Framework Position PaperDocument16 paginiITK Arctic Policy Framework Position PaperNunatsiaqNewsÎncă nu există evaluări

- MPSC EnglishDocument3 paginiMPSC EnglishManoj AvhadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Information Sheet 13-5 FlsDocument5 paginiInformation Sheet 13-5 FlsDcs JohnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project Organisation (Self Study)Document30 paginiProject Organisation (Self Study)Jatin VanjaniÎncă nu există evaluări

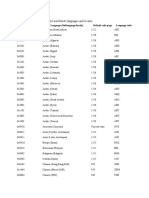

- The Following Table Shows The Worldwide Languages and LocalesDocument12 paginiThe Following Table Shows The Worldwide Languages and LocalesOscar Mauricio Vargas UribeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amy Claire ThompsonDocument4 paginiAmy Claire Thompson_amyctÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rizal As A TeacherDocument12 paginiRizal As A TeacherKristine AgustinÎncă nu există evaluări