Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

WJG 19 9003 PDF

Încărcat de

Theodore LiwonganTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

WJG 19 9003 PDF

Încărcat de

Theodore LiwonganDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Online Submissions: http://www.wjgnet.

com/esps/ World J Gastroenterol 2013 December 21; 19(47): 9003-9011

bpgoffice@wjgnet.com ISSN 1007-9327 (print) ISSN 2219-2840 (online)

doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i47.9003 © 2013 Baishideng Publishing Group Co., Limited. All rights reserved.

MINIREVIEWS

Pancreatic trauma: A concise review

Uma Debi, Ravinder Kaur, Kaushal Kishor Prasad, Saroj Kant Sinha, Anindita Sinha, Kartar Singh

Uma Debi, Division of GE Radiology, Department of Super- visualized within several hours following trauma as they

speciality of Gastroenterology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical are time dependent. Delayed diagnoses of traumatic

Education and Research, Chandigarh 160 012, India pancreatic injuries are associated with high morbidity

Ravinder Kaur, Department of Radiodiagnosis, Government and mortality. Imaging plays an important role in diag-

Medical College and Hospital, Chandigarh 160 012, India

nosis of pancreatic injuries because early recognition of

Kaushal Kishor Prasad, Division of GE Histopathology, Depart-

ment of Superspeciality of Gastroenterology, Postgraduate Insti- the disruption of the main pancreatic duct is important.

tute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh 160 012, We reviewed our experience with the use of various

India imaging modalities for diagnosis of blunt pancreatic

Saroj Kant Sinha, Kartar Singh, Department of Superspeciality trauma.

of Gastroenterology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education

and Research, Chandigarh 160 012, India © 2013 Baishideng Publishing Group Co., Limited. All rights

Anindita Sinha, Department of Radiodiagnosis, Postgraduate In- reserved.

stitute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh 160 012,

India Key words: Pancreas; Trauma; Pancreatitis; Radiology

Author contributions: Debi U, Kaur R and Sinha SK contrib-

uted equally in generating the figures and writing the article;

Core tip: The pancreas is a relatively uncommon organ

Prasad KK substantially contributed to conception, designing and

writing of the article; Sinha A contributed in writing of the arti- to be injured in abdominal trauma and difficult to diag-

cle; Singh K contributed in revising the article critically and gave nose. Pancreatic injuries are usually subtle to identify

final approval of the version to be published. by different diagnostic imaging modalities and these

Correspondence to: Kaushal Kishor Prasad, MD, PDC, CFN, injuries are often overlooked in cases with extensive

MAMS, FICPath, Additional Professor, Chief, Division of GE multiorgan trauma. They are associated with consider-

Histopathology, Department of Superspeciality of Gastroenterol- ably high morbidity and mortality in cases of delayed

ogy, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, diagnosis, incorrect classification of the injury, or delays

Chandigarh 160 012, India. kaushalkp10@hotmail.com in treatment. This review provides an overall concise

Telephone: +91-172-2756604 Fax: +91-172-2744401

update on pancreatic trauma and highlights the find-

Received: June 4, 2013 Revised: September 15, 2013

Accepted: October 19, 2013 ings of pancreatic trauma on various imaging modalities.

Published online: December 21, 2013

Debi U, Kaur R, Prasad KK, Sinha SK, Sinha A, Singh K. Pan-

creatic trauma: A concise review. World J Gastroenterol 2013;

19(47): 9003-9011 Available from: URL: http://www.wjgnet.

Abstract com/1007-9327/full/v19/i47/9003.htm DOI: http://dx.doi.

Traumatic injury to the pancreas is rare and difficult org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i47.9003

to diagnose. In contrast, traumatic injuries to the

liver, spleen and kidney are common and are usually

identified with ease by imaging modalities. Pancreatic

injuries are usually subtle to identify by different diag- INTRODUCTION

nostic imaging modalities, and these injuries are often

overlooked in cases with extensive multiorgan trauma. The pancreas is a relatively uncommon organ to be in-

The most evident findings of pancreatic injury are post- jured in trauma, occurring in less than 2% of blunt trau-

traumatic pancreatitis with blood, edema, and soft ma cases, and this injury is associated with considerably

tissue infiltration of the anterior pararenal space. The high morbidity and mortality in cases of delayed diagno-

alterations of post-traumatic pancreatitis may not be sis, incorrect classification of the injury, or delays in treat-

WJG|www.wjgnet.com 9003 December 21, 2013|Volume 19|Issue 47|

Debi U et al . Pancreatic trauma

ment[1,2]. Mortality for pancreatic injuries ranges from 9% exsanguinating hemorrhage, which is a frequent cause

to 34%; however, only 5% of the pancreatic injuries are of death in patients with a pancreatic injury. The splenic

directly related to the fatal outcome. Physical examination artery and splenic vein run superior and posterior to the

is usually not reliable in the setting of acute pancreatic body and tail of the pancreas and are relatively easier to

trauma[3]. Early and accurate diagnosis can decrease mor- expose and control compared to the IVC and portal vein.

bidity and mortality, and various imaging modalities play The vascular anatomy causes problems in repairing the

a key role in recognition of pancreatic injuries[4,5]. injuries to the head of the pancreas whereas injuries to

Knowledge about the mechanisms of pancreatic in- the body and tail are easier to manage[11,12].

jury, the presence of coexisting injuries, the time to diag-

nosis, the presence or absence of major ductal injury, and

the roles of various imaging modalities is essential for PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF INJURY

prompt, early and accurate diagnosis. Early detection of Injuries to the pancreas most commonly result from

disruption of the main pancreatic duct is of paramount penetrating trauma caused by gunshot or stab wounds

importance because such disruption is the main cause of and occur in approximately 20%-30% of all patients with

delayed complications like pseudopancreatic cyst[6]. The penetrating traumas. The penetrating injury caused by

most common site of traumatic pancreatic injury is at the firearms results in the highest frequency of pancreatic

junction of the body and tail. Significant pancreatic injury trauma. The relatively protected retroperitoneal location

may occur in the absence of abnormality on various im- of the pancreas protects it from most instances of blunt

aging modalities. abdominal trauma. Blunt trauma to the pancreas is, in

Pancreatic trauma occurs commonly in connection most instances, caused by a sudden localized force to the

with multiple injuries after motor vehicle accidents in upper abdomen that compresses the pancreas against the

adults and bicycle handlebar injuries in children[7]. Con- vertebral column (e.g., steering wheel injury in a motor

servative management is mainly advocated for pancreatic vehicle accident in adults and from bicycle handlebar in-

trauma without ductal injuries. Computed tomography jury or direct blow from a kick or fall in children)[8]. Blunt

(CT) is routinely used as the first-line imaging modality in pancreatic injury is more common in children and young

acute abdominal trauma cases and is helpful in recogniz- adults because they have a thinner or absent mantle of

ing injuries to the pancreas and other organs and their as- protective fat, which surrounds the pancreas in older

sociated complications[8]. Ultrasonography (US) is useful adults[10]. In order of frequency, injuries to the pancreas

in cases of pancreatic ascites and pseudocyst formation, involve the body, head and tail. Pancreatic injury is rarely

which are more likely to occur in cases with traumatic a solitary injury, and in the majority of instances there is

pancreatitis[3,9]. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatog- at least one coexistent injury; 60% are duodenopancreatic

raphy (MRCP) allows direct imaging of the pancreatic lesions, while 90% involve at least one other abdominal

duct and its disruption[10]. The purpose of this paper is to organ[1]. Therefore, multiple organ injuries are a red flag

review the findings of pancreatic trauma on various im- suggesting the possibility of coexistent pancreatic injury.

aging modalities.

CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS Patients with pancreatic trauma present usually with fea-

The pancreas is a long J-shaped, soft, lobulated retroperi- tures of acute pancreatitis. The typical clinical triad of

toneal organ. It is situated transversely across the poste- pancreatic trauma is upper abdominal pain, leukocytosis,

rior abdominal wall, at the back of the epigastric and left and elevated serum amylase level, that may, however, be

hypochondriac regions at level of lumbar (L1-2) spine absent in adults during the first 24 h and even for sev-

(Figure 1). In adults, the pancreas is about 15-20 cm long, eral days[12,13]. Pancreatic trauma is difficult to recognize

1.0-1.5 cm thick and weighs approximately 90-100 g[11]. because of coexisting injuries to other intra-abdominal

The main pancreatic duct of Wirsung traverses the entire organs and its retroperitoneal location, which makes

length of the gland. The superior pancreaticoduodenal signs and symptoms less marked, and consequently this

artery from the gastroduodenal artery and the inferior trauma ends up causing higher morbidity and mortality

pancreaticoduodenal artery from the superior mesenteric rates than observed in injuries to other intra-abdominal

artery run in the concave contour of the second part organs[14,15]. Symptoms of injury to other intra-abdominal

of the duodenum to supply the head of the pancreas. organs or structures commonly mask or supersede that

The pancreatic branches of the splenic artery supply the of pancreatic injury, both early and late in the course of

neck, body and tail of the pancreas. The body and neck trauma. Therefore, a high degree of suspicion is required

of the pancreas drain into the splenic vein, whereas the to ensure that pancreatic injuries are not overlooked or

head drains into the superior mesenteric and portal veins. missed either early or late in their course.

The lymphatic drainage of the pancreas is via the splenic,

celiac and superior mesenteric lymph nodes. The proxim-

ity of many larger vessels such as the inferior vena cava LABORATORY FINDINGS

(IVC), portal vein and abdominal aorta makes injuries to Raised amylase in serum or diagnostic peritoneal la-

the pancreas difficult to manage because of the risk of vage (DPL) fluid can be useful in diagnosis, but there is

WJG|www.wjgnet.com 9004 December 21, 2013|Volume 19|Issue 47|

Debi U et al . Pancreatic trauma

Aorta T

Inferior vena cava

Tail

Body

Common bile duct Neck

Duodenum

Pancreatic duct

Head

Superior

Uncinate process

mesenteric artery

Superior

mesenteric vein

Figure 1 Gross anatomy of the pancreas.

Figure 2 Ultrasound image. Axial ultrasound image shows localized traumatic

enlargement of the pancreas with diffuse edema. Transection of distal body of

pancreas communicating with large fluid collection anterior to pancreas (white

poor correlation between raised amylase and pancreatic

arrow).

trauma because amylase may be elevated in injuries of

the salivary gland, in duodenal trauma, hepatic trauma,

and injuries to the head and face, and in an intoxicated reliable in the follow-up of complications such as pseu-

patient[16-18]. A raised amylase level after blunt pancreatic docysts. Real-time contrast-enhanced US is an effective

trauma is time dependent, and a persistently elevated or technique in emergency imaging, but its role should not

a rising amylase level is a more reliable indicator of pan- be considered as a replacement for CT[20].

creatic trauma, but it does not indicate the severity of the US may show localized traumatic enlargement of the

injury[14]. Amylase detected in DPL fluid is a much more pancreas or diffuse edema simulating inflammatory pan-

sensitive and specific indicator of pancreatic injury than creatitis. In trauma patients, peripancreatic fluids may be

blood or serum amylase estimations. Serum lipase activity a sign of pancreatic contusion[21]. A traumatic pseudocyst

is also not specific for pancreatic injury[12]. of the pancreas may be detected by US and monitored

on serial examinations. Since complications of trauma

are most likely to occur from rupture or stenosis of the

RADIOLOGIC STUDIES main pancreatic duct, it is important to try to delineate

Diagnostic imaging plays an important role in the recog- this structure in all cases of pancreatic injury. Transection

nition, evaluation, and follow-up of traumatic pancreatic throughout the pancreas parenchyma is suggestive of

injuries. The imaging findings in patients with pancreatic ductal injury (Figure 2).

trauma are nonspecific and often indistinguishable from

those of inflammatory pancreatitis. CT

CT is the simplest and least invasive diagnostic modality

Conventional radiography currently available for evaluating suspected pancreatic

A plain X-ray of the abdomen in patients with pancreatic trauma and its complications, because of the subtlety of

trauma is nonspecific and none of the radiologic abnor- the US findings. However, this study is only rarely useful

malities on plain films can be used for specific diagnostic in acute penetrating injury. Computed tomography is the

purposes. Conventional radiography can be valuable in radiographic examination of choice for hemodynamically

detecting penetrating trauma by visualizing and localizing stable patients with abdominal trauma as it provides the

foreign bodies such as bullet fragments and projectile- safest and most comprehensive means of diagnosis of

induced bony injury, as well as pulmonary parenchymal traumatic pancreatic injury[10].

injury, gastric dilatation and pneumoperitoneum. The pancreas may appear normal in 20%-40% of

Findings are often indistinguishable from those of patients when CT is performed within 12 h after trauma

inflammatory pancreatitis. Pancreatic hemorrhage and because pancreatic injuries may produce little change in

edema widen the duodenal sweep with distension of the the density which may not be detectable on CT scan[1,22].

duodenum. Dissection along the transverse mesocolon In addition, there may be minimal separation of lacer-

results in gaseous distension of the colon, which may ter- ated pancreatic fragments (Figure 3A). Currently, mul-

minate abruptly usually at the splenic flexure to produce tidetector-row CT scanners are used for evaluation of

the “colon-cutoff sign”. A sentinel loop representing abdominal trauma cases as they are faster to scan, which

localized ileus may be seen in the mid-abdomen. greatly reduces bowel artifacts and resolves many previ-

ous technical problems[8]. Lacerations tend to occur at the

US junction of the body and tail due to shearing injuries with

Although US is easy to perform, portable and cost- compression against the spine (Figure 3A).

effective, pancreatic injuries are difficult to diagnose in Direct signs of pancreatic injury include laceration,

spite of technically adequate sonograms[19]. However, it is transection, focal pancreatic enlargement and inhomo-

WJG|www.wjgnet.com 9005 December 21, 2013|Volume 19|Issue 47|

Debi U et al . Pancreatic trauma

Figure 3 Computed tomography images.

A B A, B: Axial contrast-enhanced computed

tomography shows a heterogeneous appear-

ance of the body and tail of pancreas with a

linear laceration (white arrow) across the dis-

tal body of the pancreas. There is also fluid

in the lesser sac, perihepatic space, peri-

splenic space and hemoperitoneum. There

is free air into chest wall muscles on right

side in a case of blunt pancreatic trauma (A),

and transection throughout extent of pan-

creatic parenchyma in proximal body region

(suggestive of ductal injury) with a large fluid

collection (white arrow) anterior to pancreas

communication with the transection in an-

C D other case of blunt injury to upper abdomen

(B); C: Contrast-enhanced computed tomog-

raphy demonstrating mild diffuse hypoden-

sity of the body of pancreas. Contusions of

the head and neck also demonstrated (white

arrow) with secondary signs of traumatic

pancreatitis, i.e., increased density of the

peripancreatic fat, thickening of left anterior

pararenal fascia, fluid in the lesser sac and

hemoperitoneum; D: Plain axial computed

tomography section at the level of pancreas

shows a large hyperdense hematoma (black

arrow) in proximal body of pancreas sug-

gestive of pancreatic injury. E: Multiplanar

reconstruction image of contrast-enhanced

E F computed tomography demonstrating a pan-

creatic fracture (white arrow) in neck region

with separation of pancreatic fragments; F:

Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomog-

raphy scan in a child with bicycle handlebar

injury more than a month old shows a large

lobulated pseudocyst anterior to pancreas

communicating with pancreatic laceration

in the neck of pancreas representing ductal

injury. There is fluid between posterior pan-

creas and the splenic vein (arrow heads).

geneous enhancement. Fluid collections like hematoma injuries[7]. So it is important that imaging focuses on the

and pseudocyst are usually seen communicating with the integrity of the duct or findings that suggest damage to

pancreas at the site of laceration or transection (Figure the pancreatic duct. The accuracy of detecting a major

3B). Secondary signs include peripancreatic fat stranding, ductal injury by CT has been reported to be as low as

peripancreatic fluid collections, fluid between the splenic 43%[10,17,29-31].

vein and pancreas, hemorrhage, thickening of the left an- Computed tomography may not always directly dem-

terior pararenal fascia and associated injuries to adjacent onstrate the ductal disruption; injury to the duct can be

structures[10] (Figure 3C, Table 1). suggested based on the degree of parenchymal injury and

Contusion appears as focal or diffuse low attenua- can only be inferred following visualization of a through

tion areas and laceration is seen as a linear hypodense and through laceration of the pancreas (Figure 3E). A

line perpendicular to the long axis of the pancreas[6,23,24]. computed tomography grading scheme has been devised

Pancreatic fracture on CT is diagnosed if there is a clear (Table 2), which parallels the surgical classification of

separation of fragments across the long axis of the pan- Moore[10,32]. Grade A injuries with laceration involving <

creas[25]. Intrapancreatic hematoma is a very specific sign 50% pancreas are usually seen with an intact pancreatic

of pancreatic injury[26] (Figure 3D). Fluid between the duct by surgical grading, whereas grade B and C injuries

splenic vein and pancreas is a very non-specific sign but correlate with duct disruption, especially when CT shows

it may suggest pancreatic injury if associated with his- deep lacerations or pancreatic transection[32]. Overestima-

tory of blunt abdominal trauma[27]. Pseudocysts are more tion on CT can occur in grade CⅠ and CⅡ injuries if

likely to occur in patients with traumatic pancreatitis[28]. merely deep lacerations or “single scan” transections are

The risk of abscess or fistula formation in patients with identified at the pancreatic head. However, urgent en-

disruption of the pancreatic duct approaches 25% and doscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

50%, respectively, in comparison with 10% without duct may be quite valuable in such patients with strong clinical

WJG|www.wjgnet.com 9006 December 21, 2013|Volume 19|Issue 47|

Debi U et al . Pancreatic trauma

Table 1 Computed tomographic signs of pancreatic injury Table 3 Classification of pancreatic injuries by endoscopic

retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Specific signs Fracture of the pancreas

Pancreatic laceration Grade Description

Focal or diffuse pancreatic enlargement/edema

Ⅰ Normal main pancreatic duct on ERCP

Pancreatic hematoma

Ⅱa Injury to branches of main pancreatic duct on ERCP with

Active bleeding/extravasation of intravenous contrast

contrast extravasation inside the parenchyma

Fluid separating the splenic vein from posterior aspect of

Ⅱb Injury to branches of main pancreatic duct on ERCP with

pancreas

contrast extravasation into the retroperitoneal space

Non-specific Inflammatory changes in peripancreatic fat and mesentery

Ⅲa Injury to the main pancreatic duct on ERCP at the body or

signs Fluid surrounding the superior mesenteric artery

tail of the pancreas

Thickening of the left anterior renal fascia

Ⅲb Injury to the main pancreatic duct on ERCP at the head

Pancreatic ductal dilatation

the pancreas

Acute pseudocyst formation/peripancreatic fluid

collection

Reproduced from Takishima et al[38]. ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholan-

Fluid in the anterior and posterior pararenal spaces

Fluid in transverse mesocolon and lesser sac giopancreatography.

Hemorrhage into peripancreatic fat, mesocolon and

mesentery

Extraperitoneal fluid in up to 97% of cases and within the pancreatic tail in

Intraperitoneal fluid up to 83%[35]. In addition, MRCP may demonstrate ab-

normalities not visible at ERCP, such as fluid collections

upstream of the site of duct transection (Figure 4A), and

Table 2 Computed tomographic grading of blunt pancreatic is helpful in assessing parenchymal injury[36]. For assess-

injuries ing the parenchyma, fat-suppressed T1- and T2-weighted

sequences are performed. Magnetic resonance pancreato-

CT grading CT findings of blunt pancreatic injury grams are acquired by using heavily T2-weighted breath-

Grade A Pancreatitis and/or superficial lacerations at any site hold or non-breath-hold sequences. Fast spin-echo (two-

Grade B dimensional or three-dimensional) and rapid acquisition

BⅠ Deep laceration at distal pancreas with relaxation enhancement sequences performed in the

BⅡ Transections at distal pancreas

Grade C

coronal and axial planes are usually sufficient[10].

CⅠ Deep lacerations at proximal pancreas

CⅡ Transections at proximal pancreas ERCP

ERCP is increasingly being used to help in both early

Reproduced from Wong et al[32]. CT: Computed tomography. and in delayed diagnosis of pancreatic ductal injuries in

patients with strong clinical evidence of pancreatic injury

evidence of pancreatic injury and an equivocal CT scan, and an equivocal CT scan. Endoscopic retrograde chol-

to establish the final diagnosis[10,32]. A patient with a post- angiopancreatography is the most accurate investigation

traumatic pseudocyst should be considered to have a for diagnosing the site and extent of ductal injury by

ductal leak until proven otherwise[1] (Figure 3F). demonstrating extravasation or a cutoff, especially in pa-

tients with delayed presentations[37]. It can be performed

MRCP preoperatively, intraoperatively or postoperatively in pa-

Since the outcome of pancreatic trauma patients largely tients with pancreatic injury. Although ERCP is the most

depends upon the integrity of the pancreatic duct, evalu- useful procedure for the diagnosis of pancreatic ductal

ation of the duct is essential. In the past, ERCP was injury in stable patients, surgery should be considered in

the only method available for evaluating pancreatic duct hemodynamically unstable patients. A classification of

integrity. More recently, MRCP has emerged as an at- pancreatic injuries (Table 3) has been devised according

tractive alternative non-invasive diagnostic tool for direct to the findings on ERCP[38]. Although MRCP (Figure 4B)

imaging of the pancreatic duct and it is being used more has become the noninvasive imaging method of choice

frequently to assess injury to the ductal components[33]. when evaluating for pancreatic duct injury, ERCP re-

Dynamic secretin-stimulated (DSS) MRCP is a varia- mains important because of its potential to direct image-

tion on standard MRCP and may compete with ERCP guided therapy (Figure 5). Endoscopic retrograde chol-

in diagnostic accuracy. Like ERCP, DSS MRCP provides angiopancreatography in selected patients allows non-

dynamic information as to whether there is continu- operative treatment in the absence of ductal injury and

ing leakage from an injured main pancreatic duct. The earlier operative treatment or primary therapy as stent

advantages of DSS MRCP include it being noninvasive, placement in the presence of ductal injury[39]. It also aids

faster and more readily available than ERCP, and it can the treatment of late complications of pancreatic duct

illustrate the entire pancreatic parenchymal and duc- injuries such as pseudocysts and pancreatic fistulae. Both

tal anatomy, as well as pathologic fluid collections and endoscopic transpapillary and transmural drainage are ef-

ductal disruptions[34]. The main pancreatic duct (MPD) fective options for managing delayed local complications

can be identified by MRCP within the pancreatic head of pancreatic trauma. The endoscopist must be skilled

WJG|www.wjgnet.com 9007 December 21, 2013|Volume 19|Issue 47|

Debi U et al . Pancreatic trauma

Figure 4 Magnetic resonance images. T2 weighted

A B axial image (A) and magnetic resonance cholangio-

pancreatography (B) in a case of traumatic pancreatitis

show heterogenous signal intensity of pancreas with

peripancreatic stranding. Main pancreatic duct is dilated

in the body and tail region (black arrow). A lobulated

pseudopancreatic cyst is seen in lesser sac anterior as-

pect of body of pancreas (white arrow) demonstrated in

magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography.

10 cm

Table 4 American Association for the surgery of trauma

classification of pancreatic trauma

Grade Injury Description

Ⅰ Hematoma Minor contusion without ductal injury

Laceration Superficial laceration without ductal injury

Ⅱ Hematoma Major contusion without ductal injury or tissue loss

Laceration Major laceration without ductal injury or tissue loss

Ⅲ Laceration Distal transection or pancreatic parenchymal injury

with ductal injury

Ⅳ Laceration Proximal transection or pancreatic parenchymal

injury involving the ampulla

Ⅴ Laceration Massive disruption of the pancreatic head

Reproduced from Campbell et al[42].

Figure 5 Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography image. Anoth-

er case of traumatic pancreatitis. Fluoroscopic image showing main pancreatic

duct disruptions during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with

multiple contrast filled outpouching is seen, suggestive of pseudocysts (white

common complications. Other less frequent complica-

arrow). Multiple contrast filled tracts are also visualized (black arrowhead). Few tions include peritonitis, intestinal obstruction, gastro-

tracts are seen in retroperitoneum and one of the tracts is reaching into medias- intestinal bleeding, endocrine or exocrine insufficiency,

tinum (black arrow). Endoscope is visible. splenic artery pseudoaneurysm formation or rupture and

splenic vein thrombosis[6,24].

and experienced in its use as this procedure has potential

complications that can limit its usefulness in patients with CLASSIFICATION AND GRADING OF

pancreatic trauma. PANCREATIC INJURIES

Pancreatic injuries are classified and graded according to

COMPLICATIONS OF PANCREATIC the damage to the pancreatic parenchyma and the ductal

TRAUMA system. Grading of pancreatic injuries enables an exact

description of injuries, can influence management, and

Early diagnosis and treatment are associated with better allows a comparison of outcomes and effective quality

overall outcomes in traumatic pancreatic injury patients. control of treatment[12]. There are several classification

Mortality associated with pancreatic injuries approximates systems of traumatic pancreatic injuries[32,38] (Tables 2 and

20% and results primarily from hemorrhage caused by 3) but the pancreatic organ injury scale (OIS) proposed

injuries to other intra-abdominal organs and from sep- by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma

sis[40,41]. There is an increase in infectious complications in (AAST) fulfills most of these criteria and at present is the

patients who have pancreatic wounds co-associated with universally accepted classification scheme[43]. This OIS

injury to small and large intestine. Blunt pancreatic inju- scale involves five grades, which concedes the significance

ries without ductal leak usually resolve with mere conser- of more complex injuries to the pancreas, and particu-

vative management. On the other hand, damage to the larly those injuries affecting the pancreatic duct and the

ductal system, if inadequately treated or untreated, can pancreatic head (Table 4). This classification scheme can

result in prolonged morbidity. Complications of traumat- also be correlated with other organ injury scales, as well

ic pancreatic injury are manifold and range from minor as integrated into more complex scoring systems, such

pancreatitis to death[40,42]. Fistula formation is the most as injury severity score or trauma score - injury severity

frequently observed complication. Traumatic pancreatitis, score from which probability of survival of an individual

pseudocyst formation, abscesses and duct stricture are case is determined.

WJG|www.wjgnet.com 9008 December 21, 2013|Volume 19|Issue 47|

Debi U et al . Pancreatic trauma

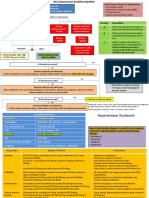

Blunt pancreatic injury Figure 6 Management algorithm for traumatic pan-

creatic injury patients. Reproduced from Ilahi et al[14].

Hemodynamically stable patient ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogra-

Helical multislice CT of abdomen phy; MRCP: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatog-

raphy.

AAST - OIS grade

High-grade blunt pancreatic injuries

Low-grade blunt pancreatic injuries

Grade Ⅲ

Grade Ⅰ

Grade Ⅳ

Grade Ⅱ

Grade Ⅴ

ERCP or MRCP Surgical intervention

Ductal injury

Yes No

Non-operative management

Surgical intervention

MANAGEMENT OF PANCREATIC grade Ⅲ or higher injuries often require resection with

possible reconstruction and/or drainage procedures[47].

INJURIES There are a number of alternative procedures that can be

Many patients with pancreatic injuries have multiple used for the management of high-grade blunt pancreatic

associated injuries including vascular and other intra- injury, such as duodenal diversion, pyloric exclusion, the

abdominal organs injury; priority must be given to stabi- Whipple procedure or simple drainage, with the choice

lizing the patient before any definitive management of dependent on the patient’s hemodynamic status and the

the pancreatic injury. The initial priorities include control presence or absence of associated duodenal injury[48,49].

of hemorrhage and spillage of intestinal contents. The Sometimes, the decision to perform a pancreaticoduo-

decision regarding therapeutic approach of the traumatic denectomy is unavoidable in select cases. If the patient

pancreatic injury, either with a conservative approach is hemodynamically unstable, pancreaticoduodenectomy

or a surgical approach, depends upon the integrity of should be performed as a two-step procedure. After the

the MPD, extent of pancreatic parenchymal damage, initial damage control surgery, anastomoses are com-

anatomical location of the injury, stability of the patient pleted at a second surgery when the patient is stable[50].

and degree of associated organ damage (Figure 6)[44]. In The standard of care in penetrating injuries is a surgi-

patients with an isolated pancreatic contusion or super- cal approach depending upon the location of the injury

ficial lacerations without ductal disruption, conservative and associated abdominal injuries. Damage control sur-

management may be warranted. Treatment of traumatic gery in hemodynamically unstable patients with massive

pancreatitis consists of bowel rest, nasogastric suction, injury to the pancreas and associated intra-abdominal

and nutritional support[29]. ERCP-guided stent placement organs reduces morbidity and mortality.

to the MPD injury has been indicated in select cases[45].

Endoscopic transpapillary drainage has been success-

CONCLUSION

fully used to heal duct disruptions in the early phase

of pancreatic trauma and in the delayed phase to treat Pancreatic injury is uncommon and usually difficult to

the complications of pancreatic duct injuries. However, diagnose. Because of the subtlety of the ultrasound find-

in patients with major ductal injury in blunt pancreatic ings, computed tomography is the preferred method

trauma cases, morbidity and mortality greatly increase for evaluating suspected pancreatic trauma; however,

unless surgery is undertaken within the first 24 h. By us- pancreatic duct injury may not be detected on computed

ing the pancreatic OIS grading system of the AAST to tomography scan except when there is through and

help to guide the appropriate surgical management, the through laceration. In select situations, including minor

morbidity and mortality in blunt pancreatic injury are de- injuries, a conservative approach may be successful. With

creased[46]. Grades Ⅰ and Ⅱ are treated with non-opera- modern imaging modalities and expertise in endoscopic

tive management techniques or simple drainage, whereas retrograde cholangiopancreatography, isolated pancreatic

WJG|www.wjgnet.com 9009 December 21, 2013|Volume 19|Issue 47|

Debi U et al . Pancreatic trauma

duct injury can be successfully managed. A surgical ap- 3510932]

proach is appropriate with major pancreatic injury that 20 Catalano O, Lobianco R, Sandomenico F, Mattace Raso M,

Siani A. Real-time, contrast-enhanced sonographic imaging

necessitates urgent surgical intervention. in emergency radiology. Radiol Med 2004; 108: 454-469 [PMID:

15722992]

21 Lenhart DK, Balthazar EJ. MDCT of acute mild (nonnecro-

REFERENCES tizing) pancreatitis: abdominal complications and fate of flu-

1 Cirillo RL, Koniaris LG. Detecting blunt pancreatic injuries. id collections. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008; 190: 643-649 [PMID:

J Gastrointest Surg 2002; 6: 587-598 [PMID: 12127126] 18287434 DOI: 10.2214/AJR.07.2761]

2 Kao LS, Bulger EM, Parks DL, Byrd GF, Jurkovich GJ. 22 Jeffrey RB, Federle MP, Crass RA. Computed tomography

Predictors of morbidity after traumatic pancreatic injury. J of pancreatic trauma. Radiology 1983; 147: 491-494 [PMID:

Trauma 2003; 55: 898-905 [PMID: 14608163] 6836127]

3 Schurink GW, Bode PJ, van Luijt PA, van Vugt AB. The val- 23 Higashitani K, Kondo T, Sato Y, Takayasu T, Mori R, Ohshi-

ue of physical examination in the diagnosis of patients with ma T. Complete transection of the pancreas due to a single

blunt abdominal trauma: a retrospective study. Injury 1997; stamping injury: a case report. Int J Legal Med 2001; 115: 72-75

28: 261-265 [PMID: 9282178] [PMID: 11724433 DOI: 10.1007/s004140100208]

4 Wong YC, Wang LJ, Lin BC, Chen CJ, Lim KE, Chen RJ. CT 24 Madiba TE, Mokoena TR. Favourable prognosis after

grading of blunt pancreatic injuries: prediction of ductal surgical drainage of gunshot, stab or blunt trauma of the

disruption and surgical correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr pancreas. Br J Surg 1995; 82: 1236-1239 [PMID: 7552005 DOI:

1997; 21: 246-250 [PMID: 9071293] 10.1002/bjs.1800820926]

5 Fischer JH, Carpenter KD, O'Keefe GE. CT diagnosis of an 25 Dodds WJ, Taylor AJ, Erickson SJ, Lawson TL. Traumatic

isolated blunt pancreatic injury. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996; fracture of the pancreas: CT characteristics. J Comput Assist

167: 1152 [PMID: 8911170] Tomogr 1990; 14: 375-378 [PMID: 2335603 DOI: 10.1097/0000

6 Bradley EL, Young PR, Chang MC, Allen JE, Baker CC, 4728-199005000-00009]

Meredith W, Reed L, Thomason M. Diagnosis and initial 26 Lane MJ, Mindelzun RE, Jeffrey RB. Diagnosis of pancre-

management of blunt pancreatic trauma: guidelines from a atic injury after blunt abdominal trauma. Semin Ultrasound

multiinstitutional review. Ann Surg 1998; 227: 861-869 [PMID: CT MR 1996; 17: 177-182 [PMID: 8845200 DOI: 10.1016/

9637549] S0887-2171(96)90015-3]

7 Sutherland I, Ledder O, Crameri J, Nydegger A, Catto- 27 Sivit CJ, Eichelberger MR. CT diagnosis of pancreatic injury

Smith A, Cain T, Oliver M. Pancreatic trauma in children. in children: significance of fluid separating the splenic vein

Pediatr Surg Int 2010; 26: 1201-1206 [PMID: 20803148 DOI: and the pancreas. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995; 165: 921-924

10.1007/s00383-010-2705-3] [PMID: 7676993 DOI: 10.2214/ajr.165.4.7676993]

8 Venkatesh SK, Wan JM. CT of blunt pancreatic trauma: 28 Loungnarath R, Blamchard H, Saint-Vil D. Blunt injuries of

a pictorial essay. Eur J Radiol 2008; 67: 311-320 [PMID: the pancreas in children. Peditr Surg Int 2010; 26:1201-1206

17709222] [PMID: 20407777 DOI: 10.1007/s00383-010-2606-5]

9 Chen CF, Kong MS, Lai MW, Wang CJ. Acute pancreatitis in 29 Wilson RH, Moorehead RJ. Current management of trauma

children: 10-year experience in a medical center. Acta Paedi- to the pancreas. Br J Surg 1991; 78: 1196-1202 [PMID: 1958984

atr Taiwan 2006; 47: 192-196 [PMID: 17180787] DOI: 10.1002/bjs.1800781017]

10 Gupta A, Stuhlfaut JW, Fleming KW, Lucey BC, Soto JA. 30 Leppäniemi A, Haapiainen R, Kiviluoto T, Lempinen

Blunt trauma of the pancreas and biliary tract: a multimodal- M. Pancreatic trauma: acute and late manifestations. Br

ity imaging approach to diagnosis. Radiographics 2004; 24: J Surg 1988; 75: 165-167 [PMID: 3349308 DOI: 10.1002/

1381-1395 [PMID: 15371615] bjs.1800750227]

11 Quinlan R. Anatomy, embryology and physiology of the 31 West OC, Jarolimek AM. Abdomen: traumatic emergencies.

pancreas. In: Shackelford RT, Zuidema GD, eds. Surgery of In: Harris JH Jr, Harris WH. The radiology of emergency

the alimentary tract. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders, 1983: 3-24 medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippioncott-Williams &

12 Linsenmaier U, Wirth S, Reiser M, Körner M. Diagnosis and Wilkins; 2000: 689-724

classification of pancreatic and duodenal injuries in emer- 32 Wong YC, Wang LJ, Lin BC, Chen CJ, Lim KE, Chen RJ. CT

gency radiology. Radiographics 2008; 28: 1591-1602 [PMID: grading of blunt pancreatic injuries: prediction of ductal

18936023 DOI: 10.1148/rg.286085524] disruption and surgical correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr

13 Meredith JW, Trunkey DD. CT scanning in acute abdomi- 1997; 21: 246-250 [PMID: 9071293 DOI: 10.1097/00004728-199

nal injuries. Surg Clin North Am 1988; 68: 255-268 [PMID: 703000-00014]

3279545] 33 Fulcher AS, Turner MA, Yelon JA, McClain LC, Broderick

14 Ilahi O, Bochicchio GV, Scalea TM. Efficacy of computed T, Ivatury RR, Sugerman HJ. Magnetic resonance cholangio-

tomography in the diagnosis of pancreatic injury in adult pancreatography (MRCP) in the assessment of pancreatic

blunt trauma patients: a single-institutional study. Am Surg duct trauma and its sequelae: preliminary findings. J Trauma

2002; 68: 704-77; discussion 704-77 [PMID: 12206605] 2000; 48: 1001-1007 [PMID: 10866243 DOI: 10.1097/00005373-

15 Akhrass R, Yaffe MB, Brandt CP, Reigle M, Fallon WF, 200006000-00002]

Malangoni MA. Pancreatic trauma: a ten-year multi- 34 Gillams AR, Kurzawinski T, Lees WR. Diagnosis of duct

institutional experience. Am Surg 1997; 63: 598-604 [PMID: disruption and assessment of pancreatic leak with dynamic

9202533] secretin-stimulated MR cholangiopancreatography. AJR

16 Cook DE, Walsh JW, Vick CW, Brewer WH. Upper abdomi- Am J Roentgenol 2006; 186: 499-506 [PMID: 16423959 DOI:

nal trauma: pitfalls in CT diagnosis. Radiology 1986; 159: 10.2214/AJR.04.1775]

65-69 [PMID: 3952332] 35 Fulcher AS, Turner MA, Capps GW, Zfass AM, Baker KM.

17 Greenlee T, Murphy K, Ram MD. Amylase isoenzymes in Half-Fourier RARE MR cholangiopancreatography: expe-

the evaluation of trauma patients. Am Surg 1984; 50: 637-640 rience in 300 subjects. Radiology 1998; 207: 21-32 [PMID:

[PMID: 6210005] 9530295]

18 Wright MJ, Stanski C. Blunt pancreatic trauma: a difficult 36 Soto JA, Alvarez O, Múnera F, Yepes NL, Sepúlveda ME,

injury. South Med J 2000; 93: 383-385 [PMID: 10798506] Pérez JM. Traumatic disruption of the pancreatic duct:

19 Jeffrey RB, Laing FC, Wing VW. Ultrasound in acute pan- diagnosis with MR pancreatography. AJR Am J Roent-

creatic trauma. Gastrointest Radiol 1986; 11: 44-46 [PMID: genol 2001; 176: 175-178 [PMID: 11133562 DOI: 10.2214/

WJG|www.wjgnet.com 9010 December 21, 2013|Volume 19|Issue 47|

Debi U et al . Pancreatic trauma

ajr.176.1.1760175] 000-00035]

37 Buccimazza I, Thomson SR, Anderson F, Naidoo NM, 44 Duchesne JC, Schmieg R, Islam S, Olivier J, McSwain N.

Clarke DL. Isolated main pancreatic duct injuries spectrum Selective nonoperative management of low-grade blunt

and management. Am J Surg 2006; 191: 448-452 [PMID: pancreatic injury: are we there yet? J Trauma 2008; 65: 49-53

16531134 DOI: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.11.015] [PMID: 18580509 DOI: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318176c00d]

38 Takishima T, Hirata M, Kataoka Y, Asari Y, Sato K, Ohwada 45 Canty TG, Weinman D. Treatment of pancreatic duct dis-

T, Kakita A. Pancreatographic classification of pancreatic ruption in children by an endoscopically placed stent. J Pe-

ductal injuries caused by blunt injury to the pancreas. J Trau- diatr Surg 2001; 36: 345-348 [PMID: 11172431 DOI: 10.1053/

ma 2000; 48: 745-751; discussion 751-752 [PMID: 10780612 jpsu.2001.20712]

DOI: 10.1097/00005373-200004000-00026] 46 Vasquez JC, Coimbra R, Hoyt DB, Fortlage D. Management

39 Kim HS, Lee DK, Kim IW, Baik SK, Kwon SO, Park JW, Cho of penetrating pancreatic trauma: an 11-year experience

NC, Rhoe BS. The role of endoscopic retrograde pancreatog- of a level-1 trauma center. Injury 2001; 32: 753-759 [PMID:

raphy in the treatment of traumatic pancreatic duct injury. 11754881 DOI: 10.1016/S0020-1383(01)00099-7]

Gastrointest Endosc 2001; 54: 49-55 [PMID: 11427841 DOI: 47 Fisher M, Brasel K. Evolving management of pancreatic in-

10.1067/mge.2001.115733] jury. Curr Opin Crit Care 2011; 17: 613-617 [PMID: 21986464

40 Heitsch RC, Knutson CO, Fulton RL, Jones CE. Delineation DOI: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834cd374]

of critical factors in the treatment of pancreatic trauma. Sur- 48 Feliciano DV, Martin TD, Cruse PA, Graham JM, Burch JM,

gery 1976; 80: 523-529 [PMID: 968736] Mattox KL, Bitondo CG, Jordan GL. Management of com-

41 Jones RC. Management of pancreatic trauma. Ann Surg 1978; bined pancreatoduodenal injuries. Ann Surg 1987; 205: 673-680

187: 555-564 [PMID: 646495 DOI: 10.1097/00000658-19780500 [PMID: 3592810 DOI: 10.1097/00000658-198706000-00009]

0-00015] 49 Chrysos E, Athanasakis E, Xynos E. Pancreatic trauma in

42 Campbell R, Kennedy T. The management of pancreatic the adult: current knowledge in diagnosis and manage-

and pancreaticoduodenal injuries. Br J Surg 1980; 67: 845-850 ment. Pancreatology 2002; 2: 365-378 [PMID: 12138225 DOI:

[PMID: 7448508 DOI: 10.1002/bjs.1800671203] 10.1159/000065084]

43 Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Malangoni MA, Jurkovich GJ, 50 Ito Y, Kenmochi T, Irino T, Egawa T, Hayashi S, Nagashima

Champion HR, Gennarelli TA, McAninch JW, Pachter HL, A, Hiroe N, Kitano M, Kitagawa Y. Endoscopic management

Shackford SR, Trafton PG. Organ injury scaling, II: Pancreas, of pancreatic duct injury by endoscopic stent placement: a

duodenum, small bowel, colon, and rectum. J Trauma 1990; case report and literature review. World J Emerg Surg 2012; 7:

30: 1427-1429 [PMID: 2231822 DOI: 10.1097/00005373-199011 21 [PMID: 22788538 DOI: 10.1186/1749-7922-7-21]

P- Reviewer: van Erpecum K S- Editor: Zhai HH

L- Editor: Logan S E- Editor: Wu HL

WJG|www.wjgnet.com 9011 December 21, 2013|Volume 19|Issue 47|

Published by Baishideng Publishing Group Co., Limited

Flat C, 23/F., Lucky Plaza,

315-321 Lockhart Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong, China

Fax: +852-65557188

Telephone: +852-31779906

E-mail: bpgoffice@wjgnet.com

http://www.wjgnet.com

I S S N 1 0 0 7 - 9 3 2 7

4 7

9 7 7 1 0 0 7 9 3 2 0 45

© 2013 Baishideng Publishing Group Co., Limited. All rights reserved.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Core Concepts in Acute Kidney InjuryDe la EverandCore Concepts in Acute Kidney InjurySushrut S. WaikarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Can Organ Failure and Infected Pancreatic Necrosis Be Used To Forecast Mortality in Patients With Gallstone-Induced PancreatitisDocument5 paginiCan Organ Failure and Infected Pancreatic Necrosis Be Used To Forecast Mortality in Patients With Gallstone-Induced PancreatitisInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Management of Pancreatic Injuries: JEJ Krige, E Jonas, SR Thomson and SJ BeningfieldDocument11 paginiThe Management of Pancreatic Injuries: JEJ Krige, E Jonas, SR Thomson and SJ BeningfieldHenry Espinoz ChavÎncă nu există evaluări

- EScholarship UC Item 14n977sgDocument7 paginiEScholarship UC Item 14n977sgcindyamandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Duodenal Trauma: Luke R Johnston, Gary Wind and Matthew J BradleyDocument9 paginiDuodenal Trauma: Luke R Johnston, Gary Wind and Matthew J BradleyHenry Espinoz ChavÎncă nu există evaluări

- Surgicalmanagementof Abdominaltrauma: Hollow Viscus InjuryDocument11 paginiSurgicalmanagementof Abdominaltrauma: Hollow Viscus Injurysyairodhi rodziÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 PB PDFDocument11 pagini1 PB PDFTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abstrak 401993 TpjuaDocument1 paginăAbstrak 401993 TpjuarejivalpÎncă nu există evaluări

- SASJS 88 508-515 wlsNAnDDocument8 paginiSASJS 88 508-515 wlsNAnDAnkita ChauhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iatrogenic Hepatopancreaticobiliary Injuries: A ReviewDocument13 paginiIatrogenic Hepatopancreaticobiliary Injuries: A ReviewJohn ShipÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gallstone Pancreatitis - CST PDFDocument5 paginiGallstone Pancreatitis - CST PDFDaniel Rosero CadenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Delayed Jejunal Perforation in ChildDocument2 paginiDelayed Jejunal Perforation in ChildpricillyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Erik Pancreatic TraumaDocument31 paginiErik Pancreatic TraumaIgnatius JesinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Resection of Complex Pancreatic Injuries: Benchmarking Postoperative Complications Using The Accordion ClassificationDocument11 paginiResection of Complex Pancreatic Injuries: Benchmarking Postoperative Complications Using The Accordion ClassificationCatalin SavinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Imaging Diagnosis of Pancreatic Cancer: A State-Of-The-Art ReviewDocument15 paginiImaging Diagnosis of Pancreatic Cancer: A State-Of-The-Art ReviewTanwirul JojoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Renal Trauma Medscape PDFDocument21 paginiRenal Trauma Medscape PDFPatricia Prabawati LCÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management of Duodenal Trauma: ReviewDocument4 paginiManagement of Duodenal Trauma: ReviewAladesuruOlumideAdewaleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pancreatic TraumaDocument11 paginiPancreatic TraumaAriniDwiYulianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abdominal Trauma - Clinical Profile and Management - A Prospective StudyDocument7 paginiAbdominal Trauma - Clinical Profile and Management - A Prospective StudyIJAR JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- DPLDocument5 paginiDPLngenevaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1757 7241 17 13 PDFDocument5 pagini1757 7241 17 13 PDFzafira anandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tbe-Cite Tbe-Cite Tbe-Cite Tbe-Cite Tbe-Cite: DOI: 10.1590/S0100-69912014000300016Document4 paginiTbe-Cite Tbe-Cite Tbe-Cite Tbe-Cite Tbe-Cite: DOI: 10.1590/S0100-69912014000300016Hanny RusliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tuberculosis Gastrointestinal PDFDocument11 paginiTuberculosis Gastrointestinal PDFRafael Andrés Hanssen HargitayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mucinous Cystic Neoplasm of Liver - Peeling Sign Mitigates A Diagnostic ConundrumDocument8 paginiMucinous Cystic Neoplasm of Liver - Peeling Sign Mitigates A Diagnostic ConundrumIJAR JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iatrogenic Urinary Tract Injuries: Etiology, Diagnosis, and ManagementDocument14 paginiIatrogenic Urinary Tract Injuries: Etiology, Diagnosis, and ManagementMoch NizamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seminars in Pediatric Surgery: Vincent Duron, MD, Steven Stylianos, MDDocument9 paginiSeminars in Pediatric Surgery: Vincent Duron, MD, Steven Stylianos, MDjuaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation and Management of Splenic Injury in Blunt Abdominal TraumaDocument32 paginiEvaluation and Management of Splenic Injury in Blunt Abdominal TraumaImam Hakim SuryonoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Postcholecystectomy Bile Duct Injury and Its Sequelae: Pathogenesis, Classification, and ManagementDocument16 paginiPostcholecystectomy Bile Duct Injury and Its Sequelae: Pathogenesis, Classification, and Managementnancy nayeli bernal laraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Blunt Abdominal and Pelvic Trauma: Abdullah Alabousi, Vincent M. Mellnick, Michael N. PatlasDocument8 paginiBlunt Abdominal and Pelvic Trauma: Abdullah Alabousi, Vincent M. Mellnick, Michael N. PatlasmithaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Correlation of Usg Findings With CT (Computed Tomography) Scan For Evaluation of Bowel PathologyDocument7 paginiThe Correlation of Usg Findings With CT (Computed Tomography) Scan For Evaluation of Bowel PathologyIJAR JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- Madhu Sud Han 2016Document13 paginiMadhu Sud Han 2016Shivaraj S AÎncă nu există evaluări

- Role of 128 Slice MDCT in Pancreatic Trauma Diagnosis and ManagementDocument16 paginiRole of 128 Slice MDCT in Pancreatic Trauma Diagnosis and ManagementIJAR JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- WES GuidelineDocument28 paginiWES Guidelinesolo surgical forumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Injury: Emir Battaloglu, Marisol Figuero, Christopher Moran, Fiona Lecky, Keith PorterDocument5 paginiInjury: Emir Battaloglu, Marisol Figuero, Christopher Moran, Fiona Lecky, Keith PorterRico IkhsaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management of Duodenal Trauma: Chinese Journal of Traumatology (English Edition) February 2011Document5 paginiManagement of Duodenal Trauma: Chinese Journal of Traumatology (English Edition) February 2011dr muddssar sattarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iaim 2015 0206 17Document13 paginiIaim 2015 0206 17fahrunisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tugas Radiologi 1Document5 paginiTugas Radiologi 1Felicia SinjayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6 Readmission With Major AbdominalDocument10 pagini6 Readmission With Major AbdominalElizabeth Mautino CaceresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cystic Lesions of The Pancreas - RadiologicEndosonographic CorrelationDocument20 paginiCystic Lesions of The Pancreas - RadiologicEndosonographic CorrelationVictor Kenzo IvanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- LP 1 - TI SurgeryDocument4 paginiLP 1 - TI Surgeryrahil4prasadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Open Pancreatic Debridement in Necrotizing Pancreatitis: ReferencesDocument2 paginiOpen Pancreatic Debridement in Necrotizing Pancreatitis: ReferencesDiego Andres VasquezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wjgo 14 1199Document12 paginiWjgo 14 1199juan uribeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Current Advances in The Management of Chronic Pancreatitis: Disease-a-MonthDocument34 paginiCurrent Advances in The Management of Chronic Pancreatitis: Disease-a-MonthNandaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Surgical Management of Necrotizing Pancreatitis AnDocument8 paginiSurgical Management of Necrotizing Pancreatitis AnNguyen Manh HuyÎncă nu există evaluări

- T OPINION Impact of Imaging in Urolithiasis Treatment PlanningDocument6 paginiT OPINION Impact of Imaging in Urolithiasis Treatment PlanningSara CifuentesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Delays in Imaging Diagnosis of Acute Abdominal PainDocument7 paginiDelays in Imaging Diagnosis of Acute Abdominal PainWillie VanegasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acute Kidney InjuryDocument10 paginiAcute Kidney InjuryMaya_AnggrainiKÎncă nu există evaluări

- Multimodality Approach For Imaging of Non-Traumatic Acute Abdominal EmergenciesDocument13 paginiMultimodality Approach For Imaging of Non-Traumatic Acute Abdominal EmergenciesfalisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Radiology: World Journal ofDocument17 paginiRadiology: World Journal ofAgamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strategies in Liver TraumaDocument9 paginiStrategies in Liver TraumaLuis Miguel Díaz VegaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aproximación Multidisciplinaria Al Diagnóstico y Tratamiento de La Obs Intestinal 2018Document124 paginiAproximación Multidisciplinaria Al Diagnóstico y Tratamiento de La Obs Intestinal 2018Jorge Nuñez LucicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hughes Necrotizing PancreatitisDocument11 paginiHughes Necrotizing PancreatitisELizabeth OlmosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Imaging in Chronic PancreatitisDocument7 paginiImaging in Chronic Pancreatitisdesy 102017135Încă nu există evaluări

- AKI common after acute strokeDocument5 paginiAKI common after acute strokeasfwegereÎncă nu există evaluări

- Renal Trauma in Pediatrics: A Current Review: Pediatric UrologyDocument8 paginiRenal Trauma in Pediatrics: A Current Review: Pediatric UrologyAndi SuhriyanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acute Pancreatitis (Annals of IM)Document16 paginiAcute Pancreatitis (Annals of IM)Jorge Armando Arrieta GalvanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Caustic Ingestion: Has The Role of The Gastroenterologist Burnt Out?Document4 paginiCaustic Ingestion: Has The Role of The Gastroenterologist Burnt Out?Ronald VillalobosÎncă nu există evaluări

- 249 FullDocument9 pagini249 FullAHMEDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Upper Urinary Tract Trauma - Campbell Walsh Urology 12th EdDocument27 paginiUpper Urinary Tract Trauma - Campbell Walsh Urology 12th EdAlexander SebastianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparitive Study of Panc-3 and Bedside Index For Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (Bisap) Scoring System To Identify Severity of PancreatitisDocument10 paginiComparitive Study of Panc-3 and Bedside Index For Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (Bisap) Scoring System To Identify Severity of PancreatitisIJAR JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- ADocument7 paginiATheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- JNC 8 Guideline Algorithm for Treating HypertensionDocument2 paginiJNC 8 Guideline Algorithm for Treating HypertensionTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- Venkat Esh 2008Document10 paginiVenkat Esh 2008Theodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 PB PDFDocument11 pagini1 PB PDFTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Venkat Esh 2008Document10 paginiVenkat Esh 2008Theodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- AC0100NAUV10NrHU0r0 Nl AdocsooNf crrsoNcvto l0 svlrv u010cDocument3 paginiAC0100NAUV10NrHU0r0 Nl AdocsooNf crrsoNcvto l0 svlrv u010cTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- 81 89 PDFDocument9 pagini81 89 PDFSuril VithalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chronic PancreatitisDocument23 paginiChronic PancreatitisAlvin YeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cellulitis 01Document3 paginiCellulitis 01Farid Fauzi A ManwanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Human Anatomy Essay Test QuestionsDocument2 paginiHuman Anatomy Essay Test QuestionsvelangniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statin Use and The Risk of Dementia in Patients With Stroke: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort StudyDocument7 paginiStatin Use and The Risk of Dementia in Patients With Stroke: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort StudyTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pathophysiology of Empty Nose Syndrome: Contemporary ReviewDocument5 paginiPathophysiology of Empty Nose Syndrome: Contemporary ReviewTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learn Dengue Clinical Case ManagementDocument1 paginăLearn Dengue Clinical Case ManagementArdhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medicine Card 2Document4 paginiMedicine Card 2Theodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Predicting bacterial conjunctivitisDocument5 paginiPredicting bacterial conjunctivitisTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medicine Card 2Document1 paginăMedicine Card 2ladki6Încă nu există evaluări

- History Taking Note CardDocument3 paginiHistory Taking Note Cardrmelendez001100% (1)

- Setting and Reaching Academic GoalsDocument2 paginiSetting and Reaching Academic GoalsTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dissection Rules and ProceduresDocument1 paginăDissection Rules and ProceduresTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book1 PDFDocument2 paginiBook1 PDFTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Osteology 1Document1 paginăOsteology 1Theodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- OSSIFIED LIGAMENTDocument3 paginiOSSIFIED LIGAMENTTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Print Endocrine System Exam FlashcardsDocument10 paginiPrint Endocrine System Exam FlashcardsTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Print Endocrine System Exam FlashcardsDocument10 paginiPrint Endocrine System Exam FlashcardsTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Personal DevelopmentDocument2 paginiPersonal DevelopmentTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Document 1Document2 paginiDocument 1Theodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- First Aid SummaryDocument4 paginiFirst Aid SummaryTheodore LiwonganÎncă nu există evaluări

- National Emergency Medical ServicesDocument129 paginiNational Emergency Medical ServicesTheodore Liwongan100% (1)

- Bls Skill SheetsDocument141 paginiBls Skill SheetsTheodore Liwongan100% (1)

- Internet. Social NetworksDocument22 paginiInternet. Social NetworksjuscatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plusnet Cancellation FormDocument2 paginiPlusnet Cancellation FormJoJo GunnellÎncă nu există evaluări

- Short EssayDocument3 paginiShort EssayBlue PuppyÎncă nu există evaluări

- I Could Easily FallDocument3 paginiI Could Easily FallBenji100% (1)

- D2 Pre-Board Prof. Ed. - Do Not Teach Too Many Subjects.Document11 paginiD2 Pre-Board Prof. Ed. - Do Not Teach Too Many Subjects.Jorge Mrose26Încă nu există evaluări

- Assignment 3-WEF-Global Competitive IndexDocument3 paginiAssignment 3-WEF-Global Competitive IndexNauman MalikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study 1Document2 paginiCase Study 1Diana Therese CuadraÎncă nu există evaluări

- 51 JointventureDocument82 pagini51 JointventureCavinti LagunaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Otis, Elisha Graves REPORTDocument7 paginiOtis, Elisha Graves REPORTrmcclary76Încă nu există evaluări

- Unit 3 Test A Test (Z Widoczną Punktacją)Document4 paginiUnit 3 Test A Test (Z Widoczną Punktacją)Kinga WojtasÎncă nu există evaluări

- ENTH 311 Course Video ReflectionDocument2 paginiENTH 311 Course Video ReflectionJeshua ItemÎncă nu există evaluări

- It - Unit 14 - Assignment 2 1Document8 paginiIt - Unit 14 - Assignment 2 1api-669143014Încă nu există evaluări

- 14.marifosque v. People 435 SCRA 332 PDFDocument8 pagini14.marifosque v. People 435 SCRA 332 PDFaspiringlawyer1234Încă nu există evaluări

- OF Ministry Road Transport Highways (Road Safety Cell) : TH THDocument3 paginiOF Ministry Road Transport Highways (Road Safety Cell) : TH THAryann Gupta100% (1)

- Cultural Briefing: Doing Business in Oman and the UAEDocument2 paginiCultural Briefing: Doing Business in Oman and the UAEAYA707Încă nu există evaluări

- Treatise On Vocal Performance and Ornamentation by Johann Adam Hiller (Cambridge Musical Texts and Monographs) (2001)Document211 paginiTreatise On Vocal Performance and Ornamentation by Johann Adam Hiller (Cambridge Musical Texts and Monographs) (2001)Lia Pestana RocheÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Power of Compounding: Why It's the 8th Wonder of the WorldDocument5 paginiThe Power of Compounding: Why It's the 8th Wonder of the WorldWaleed TariqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biochemical Aspect of DiarrheaDocument17 paginiBiochemical Aspect of DiarrheaLiz Espinosa0% (1)

- Mendoza CasesDocument66 paginiMendoza Casespoiuytrewq9115Încă nu există evaluări

- Application of Neutralization Titrations for Acid-Base AnalysisDocument21 paginiApplication of Neutralization Titrations for Acid-Base AnalysisAdrian NavarraÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Voice of PLC 1101Document6 paginiThe Voice of PLC 1101The Plymouth Laryngectomy ClubÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Would Orwell Think?Document4 paginiWhat Would Orwell Think?teapottingsÎncă nu există evaluări

- This Study Resource Was: Solving Problems Using Counting Techniques - TestDocument5 paginiThis Study Resource Was: Solving Problems Using Counting Techniques - TestVisalini RagurajanÎncă nu există evaluări

- LEGAL STATUs of A PersonDocument24 paginiLEGAL STATUs of A Personpravas naikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 018Document12 paginiChapter 018api-281340024Încă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Mass Communication Solved MCQs (Set-3)Document5 paginiIntroduction To Mass Communication Solved MCQs (Set-3)Abdul karim MagsiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ohp (2171912)Document8 paginiOhp (2171912)rajushamla9927Încă nu există evaluări

- English 2Document53 paginiEnglish 2momonunu momonunuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Write The Missing Words of The Verb To Be (Affirmative Form)Document1 paginăWrite The Missing Words of The Verb To Be (Affirmative Form)Daa NnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Metatron AustraliaDocument11 paginiMetatron AustraliaMetatron AustraliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionDe la EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (402)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityDe la EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (13)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsDe la EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (3)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityDe la EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDe la EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (78)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeDe la EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsDe la EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Techniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementDe la EverandTechniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (40)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossDe la EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (4)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDe la EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisDe la EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (8)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsDe la EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (169)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingDe la EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (33)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsDe la EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingDe la EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (5)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.De la EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (110)

- The Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesDe la EverandThe Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (34)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaDe la EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeDe la EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (253)

- The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingDe la EverandThe Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsDe la EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Recovering from Emotionally Immature Parents: Practical Tools to Establish Boundaries and Reclaim Your Emotional AutonomyDe la EverandRecovering from Emotionally Immature Parents: Practical Tools to Establish Boundaries and Reclaim Your Emotional AutonomyEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (201)

- The Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossDe la EverandThe Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (4)