Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

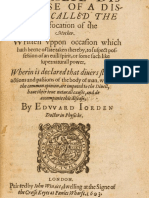

Sita Sings The Blues

Încărcat de

shubhanjali kesharwani0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

187 vizualizări5 paginiNina Paley created the unapologetically quirky, irreverent,

and unconventionally animated film Sita Sings the

Blues after her own divorce from her husband. She saw in

the tale of Ramayana, which the film juxtaposes with the

story of Nina’s own divorce, “the greatest break-up story

ever told.” The film tells the tragic story of Sita, who was

first kidnapped by Ravana and then cast away (twice) by her

husband Rama on suspicions of infidelity.

Titlu original

Sita Sings the Blues

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentNina Paley created the unapologetically quirky, irreverent,

and unconventionally animated film Sita Sings the

Blues after her own divorce from her husband. She saw in

the tale of Ramayana, which the film juxtaposes with the

story of Nina’s own divorce, “the greatest break-up story

ever told.” The film tells the tragic story of Sita, who was

first kidnapped by Ravana and then cast away (twice) by her

husband Rama on suspicions of infidelity.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

187 vizualizări5 paginiSita Sings The Blues

Încărcat de

shubhanjali kesharwaniNina Paley created the unapologetically quirky, irreverent,

and unconventionally animated film Sita Sings the

Blues after her own divorce from her husband. She saw in

the tale of Ramayana, which the film juxtaposes with the

story of Nina’s own divorce, “the greatest break-up story

ever told.” The film tells the tragic story of Sita, who was

first kidnapped by Ravana and then cast away (twice) by her

husband Rama on suspicions of infidelity.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 5

Sita Sings the Blues

Nina Paley created the unapologetically quirky, irreverent,

and unconventionally animated film Sita Sings the

Blues after her own divorce from her husband. She saw in

the tale of Ramayana, which the film juxtaposes with the

story of Nina’s own divorce, “the greatest break-up story

ever told.” The film tells the tragic story of Sita, who was

first kidnapped by Ravana and then cast away (twice) by her

husband Rama on suspicions of infidelity.

However, this tale of woe is narrated anything but tragically.

Sita’s story is peppered with the wildly anachronistic jazz

songs of 1920s singer Annette Hanshaw. An impossibly

curvy Sita thus sings of her woes to the upbeat tempo of

Hanshaw’s numbers, like when she sultrily croons “My Man

Don’t Love Me No More” when Rama abandons her. Paley’s

Sita reacts to her tragedy with trills instead of tears,

abandoning a woe-is-me approach in favour of waist-shaking

foot-tapping jazz numbers, which are, let’s face it, way more

fun. (Also, this film gave me the rather valuable information

that calling one’s lover “daddy” is not a modern-day sexy

black woman thing, because Annette Hanshaw beat

Beyoncé to it by decades. Paley’s Sita parrots Hanshaw in a

plaintive song titled “Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home?”

whilst waiting for Rama to rescue her from Lanka.)

Now we all know that the Ramayana is no feminist

masterpiece. Sita follows her husband Rama to the forest,

and then remains devoted to him despite the horrible way he

treats her, volunteering for an agni pariksha (trial-by-fire) to

prove her purity when he questions her faithfulness to him.

(She does kind of kick ass as a single mom in the forest

though, when she raises the two sons of the husband who

banished her when she was pregnant.) Rama however, in

popular cultural opinion, is held up as the absolute icon

of dharma and virtuousness. His flaws as a husband are

excused as the sacrifices required for kingship, where of

course, treating women kindly isn’t a priority. And Sita’s

submissive nature has long been held up as a model of

wifeliness in India. Nationalist leaders have often urged

Indian women to adopt her virtues of pativrata (devotion to

husband) in order to attain that “Perfect Wife” status that

Sita endorsed so well in her multiple sacrifices for her

husband.

However, Paley, like millions of other women in India, found

in Sita a resonance of her own marital frustration. In a

culture where divorce is hardly ever an option, and women

are often given little to no power in the fate of their

marriages, Sita occupies the status of an everywoman. Like

the many women who have retold the Ramayana, Paley

deals with her grief at her hurtful husband by channelling a

fierce sympathy for Sita’s treatment at the hands of Rama.

Paley does this by subtly criticizing Rama, stripping him of

his much-touted “divine virtue”. Well, actually not so subtly.

Rather hilariously, Rama’s estranged sons, Lava and Kusha

sing a song in praise of their absentee father, as taught to

them by the poet-sage Valmiki. This song, starting out nice

and well with “Rama’s great, Rama’s good, Rama does what

Rama should,” quickly descends into a nursery-rhyme style

singalong where the twins dutifully intone:

“Sing his love, sing his praise,

Rama set his wife ablaze.

Got her home, kicked her out,

To allay his people’s doubt.”

Paley’s light-hearted jabs at Rama are an act of resistance

towards male-dominated narratives of the Ramayana that

paint Rama as the ultimate man of dharma. By making an

antagonist out of the usually infallible Rama, Paley launches

a critique of his deeply patriarchal and unfair behaviour

towards Sita.

But Paley’s critique of the Ramayana goes beyond simply

championing Sita’s story over Rama’s. In the gentle,

irreverent, humorous way she tells this story, she’s also

criticizing the monolithic, heavy-handed and hegemonic

version of the Ramayana that have been espoused by the

Hindu right in the country. The Ramayana is a myth, passed

on through oral traditions, from grandmother to grandchild in

countless households in India. Yet, when scholar A. K.

Ramanujam wrote an essay on the 300 Ramayanas that he

believed existed in the Indian subcontinent, it was banned

by the Hindutva right for being sacrilegious. The very nature

of mythologies is its plurality. They arise from hundreds of

different sources and interweave with local beliefs and

traditions in delightfully interesting manifestations. The

enforcement of a unitary notion of the Ramayana strips

away at these multitudes.

Sita Sings the Blues loosely follows the dominant Valmiki

version of the epic. However, the story is narrated and

commented upon by three faceless narrators, who recount

the story of the epic from memory – completely unscripted.

These narrators sound much like my friends and me – urban,

educated Indians having a chat over cups of chai and Marie

biscuits. And much like my friends and me, they are often

iffy about the details of the epic. The film starts with them

arguing over when the Ramayana was supposed to have

happened. One says the 14th century, while the other scoffs

at her and says that that’s when the Mughals were probably

in India, so it must have been in the BC. Eventually, they

settle on “a long, long, time ago.”

They jokingly allude to this sacrosanct nature of the

Ramayana that they might accidentally be defiling with their

ignorance. One of the narrators says, “I’m messing up the

names… God, they’re going to be after me!” And on another

occasion, the narrators all wonder why Sita couldn’t just go

back with Hanuman, instead of waiting for Rama to come

save her, thereby avoiding this huge, messy war. They end

with, “Don’t challenge these stories, yaar!” (And if Hindutva

hell is a thing, these narrators definitely earned their place

in it when they wondered if Rama and Sita were part of the

Mile-High Club, considering Sita became pregnant so quickly

after her airborne voyage back home from Lanka.)

The story itself, when not being narrated, is told with these

2-D animations, wherein the animation styles keep varying –

sometimes psychedelic, sometimes old-school Indian art,

sometimes cartoon-like. In these animations, the characters

of the Ramayana speak to each other in painfully ornate

tones, keeping in character of ‘a long, long, time ago’, but

occasionally break character to deliver golden lines like,

“Your ass is grass.” For example, when Dasaratha banishes

Rama, he delivers a long, sonorous speech on how he must

keep his word to his wife Kaikeyi. After he’s done, Kaikeyi

dryly adds, “Don’t let the door hit your ass on the way out!”

Paley’s irreverence with the handling of this epic gently

mocks the strict unilateral understanding of the Ramayana

championed by right-wing groups. Far from being

blasphemous, what Paley does is reclaim the narrative for

herself. She dislodges it from its status as religious doctrine

and brings it back to the realm of myth, which is malleable

to imagination. She takes this reclamation one step further,

reclaiming it not just for herself, but every single viewer.

The film’s opening credits read, “Your Name Here

presents…” and then goes on to display its producers,

“Funded by You”. The audience thus become stakeholders in

the narrative. Paley actively encourages the audience to

make the story our own, reminding us that the Ramayana

can be ours as much as it was Valmiki’s or Tulsidas’.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Guide Questions - Sita Sings The blues-FINALDocument2 paginiGuide Questions - Sita Sings The blues-FINALKim Joshua Guirre DañoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Isaac's MatriarchDocument28 paginiIsaac's MatriarchAmma Birago100% (1)

- Handout 7Document2 paginiHandout 7api-566167829Încă nu există evaluări

- Mage - Book of MirrorsDocument3 paginiMage - Book of MirrorsDanilo Spirito0% (2)

- Oxford University PressDocument10 paginiOxford University Pressমৃন্ময় ঘোষÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sikidy DivinationDocument17 paginiSikidy Divinationziyada kirosÎncă nu există evaluări

- MAGIC, MYSTICISM, AND THE SUPERNATURAL IN MODERN POETRY by Dustin WalbomDocument36 paginiMAGIC, MYSTICISM, AND THE SUPERNATURAL IN MODERN POETRY by Dustin Walbomj9z83fÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Wife of Bath-Canterbury TalesDocument10 paginiThe Wife of Bath-Canterbury Taleslalala12342Încă nu există evaluări

- Umbanda - Pontos RiscadosDocument2 paginiUmbanda - Pontos Riscadoskemet215100% (1)

- Witchcraft and Devil LoreDocument42 paginiWitchcraft and Devil LoreMercury Element100% (1)

- ESME ROSES - Luna Spell Craft - (6 × 9 In) PRINTDocument159 paginiESME ROSES - Luna Spell Craft - (6 × 9 In) PRINTDanijelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- SuperstitionsDocument21 paginiSuperstitionsGiot Suong HongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hertitage DanceDocument3 paginiHertitage DanceAva-Dawn BlackstockÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nigel Pennick & Michael Behrend - The Cambridge 7-Church Ley (1979)Document22 paginiNigel Pennick & Michael Behrend - The Cambridge 7-Church Ley (1979)Various TingsÎncă nu există evaluări

- AsvamedhaDocument13 paginiAsvamedhaHriliu MoorsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jyeshta DeviDocument2 paginiJyeshta DevijabbanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nagaradhane: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument3 paginiNagaradhane: From Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediaanirudh.r.s.Încă nu există evaluări

- The Dark Lord of The Dark Room: DR Shraddha AshapureDocument6 paginiThe Dark Lord of The Dark Room: DR Shraddha AshapureTJPRC PublicationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hasta 210513 005550Document9 paginiHasta 210513 005550Su MÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interview With John Michael Greer by Kala Ambrose of Explore Your Spirit - Part 1 of 3-10-17-2009Document7 paginiInterview With John Michael Greer by Kala Ambrose of Explore Your Spirit - Part 1 of 3-10-17-2009liboaninoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Elemental Oracle Alchemy Science Magic Stacey Demarco 4d8dddcDocument4 paginiThe Elemental Oracle Alchemy Science Magic Stacey Demarco 4d8dddcYeray SSÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Devil and HalloweenDocument4 paginiThe Devil and HalloweenMichael Luna100% (1)

- Moon Sun Witches PDFDocument8 paginiMoon Sun Witches PDFElisa MaranhoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phases of The Moon 2014Document5 paginiPhases of The Moon 2014Andréa ZunigaÎncă nu există evaluări

- No Church in The WildDocument11 paginiNo Church in The WildAmma BiragoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Second Circle (Lust) : Are Rotting in The Rain and Hail Under The Guard of CerberusDocument9 paginiSecond Circle (Lust) : Are Rotting in The Rain and Hail Under The Guard of CerberusBladimyr GuzmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bloodlines 4Document114 paginiBloodlines 4AsetWeretHekau100% (1)

- Study Guide: Malaysia Wayang Kulit: About The ArtistDocument2 paginiStudy Guide: Malaysia Wayang Kulit: About The ArtistlingkunÎncă nu există evaluări

- Durga DeviDocument2 paginiDurga Deviviky24Încă nu există evaluări

- Basic RitualDocument5 paginiBasic RitualnawazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lives of The Necromancers by Godwin, William, 1756-1836Document201 paginiLives of The Necromancers by Godwin, William, 1756-1836Gutenberg.orgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book of The DeadDocument13 paginiBook of The DeadCatherine TheGreatÎncă nu există evaluări

- HOLIIDocument10 paginiHOLIIJavier Marcelo MoraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rule 3: Binah, Saturn Justice, Enlightenment - Understanding How The Universe WorksDocument33 paginiRule 3: Binah, Saturn Justice, Enlightenment - Understanding How The Universe WorksAzim Mohammed100% (1)

- Energy Vampire HuntDocument2 paginiEnergy Vampire HuntThomaiBerzamaniz100% (1)

- The Vanir Norse Pantheon: by TelgarDocument3 paginiThe Vanir Norse Pantheon: by TelgarEthan JefferyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Revised ShamanismDocument16 paginiRevised ShamanismSteve LiebÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artifacts of ArcanumDocument3 paginiArtifacts of ArcanumMateus kanekoÎncă nu există evaluări

- It Could Be MagicDocument183 paginiIt Could Be Magicchg13Încă nu există evaluări

- Oh My Gods Vol 2Document370 paginiOh My Gods Vol 2gabrielleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Storytellers Saints and ScoundrelsDocument3 paginiStorytellers Saints and ScoundrelsA1I9S9H2Încă nu există evaluări

- Kutti SathanDocument2 paginiKutti Sathansonaliforex10% (1)

- Ganesha MantraDocument4 paginiGanesha MantraGaurav SalujaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Black MagicDocument7 paginiBlack MagicAlison_VicarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Category SigilsDocument4 paginiCategory SigilsStephane BallesterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sri Bhairava Stotra by Acharya AbhinavaguptaDocument10 paginiSri Bhairava Stotra by Acharya Abhinavaguptansprasad88100% (1)

- Lilith and The Red SeaDocument27 paginiLilith and The Red Seablackpetal1Încă nu există evaluări

- Tir Nan Og: The Fey RealityDocument20 paginiTir Nan Og: The Fey RealitySteampunkObrimosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sandhya: Birth Date: 10 Mar 1980 04:00:00 AM Birth Place: Palghat (Kerala), IndiaDocument12 paginiSandhya: Birth Date: 10 Mar 1980 04:00:00 AM Birth Place: Palghat (Kerala), IndiaGowthami Singh RajputÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lilith - The Shade of Night and The Eclipse of The WorldsDocument2 paginiLilith - The Shade of Night and The Eclipse of The Worldsvandinha666100% (1)

- Traditional Practices in Breath, Eyes, Memory - Edwidge DanticatDocument6 paginiTraditional Practices in Breath, Eyes, Memory - Edwidge DanticatPeter-john HydeÎncă nu există evaluări

- WomanisimDocument69 paginiWomanisimHeba ZahranÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Child Story of WiccaDocument58 paginiA Child Story of WiccagabrielleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Necromantic ProjectsDocument6 paginiNecromantic ProjectsLucas Mendes de Souza100% (1)

- Dark Souls 3 Translation StuffDocument6 paginiDark Souls 3 Translation StuffKryptonixÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns & FairiesDocument63 paginiThe Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns & Fairiesjfrenchau100% (1)

- Tech MahindraDocument264 paginiTech Mahindrashubhanjali kesharwaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crude Oil PricesDocument6 paginiCrude Oil Pricesshubhanjali kesharwaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Colleges and UniversitiesDocument19 paginiColleges and Universitiesshubhanjali kesharwaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Age Residual Plot Education Residual Plot: Regression StatisticsDocument23 paginiAge Residual Plot Education Residual Plot: Regression Statisticsshubhanjali kesharwaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sita Sings The BluesDocument5 paginiSita Sings The Bluesshubhanjali kesharwaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- NBS#177Document9 paginiNBS#177Nityam Bhagavata-sevayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Music 10 LAS Q4Document27 paginiMusic 10 LAS Q4JOSH ELORDEÎncă nu există evaluări

- FP Indore Edition 23 January 2024Document27 paginiFP Indore Edition 23 January 2024Hrushikesh ShejaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 4Document9 paginiChapter 4SONÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mahabharata For ChildrenDocument15 paginiMahabharata For Childrenthisistricky22761Încă nu există evaluări

- Management and Business Ethics Through Indian Scriptures and TraditionsDocument5 paginiManagement and Business Ethics Through Indian Scriptures and TraditionsSaai GaneshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sita in The KitchenDocument7 paginiSita in The KitchenRudraharaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jada Bharat ADocument36 paginiJada Bharat AAkash JhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- AchyutashtakamDocument7 paginiAchyutashtakamShree KanthÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yatra Yatra Raghunatha KirtanamDocument4 paginiYatra Yatra Raghunatha Kirtanamanon-782185100% (1)

- Selected Letters of M.K GandhiDocument355 paginiSelected Letters of M.K GandhiragalwarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Had Anhad: Had-Had Karke Sab Gaye, Per Behad Gayo Na KoiDocument2 paginiHad Anhad: Had-Had Karke Sab Gaye, Per Behad Gayo Na KoiDiwas Gupta50% (2)

- Hanuman PlacesDocument6 paginiHanuman Placeskazhiyur varadanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Script ShorterDocument2 paginiScript ShorterKria Celestine Manglapus0% (1)

- Ramayana: A Summary by Stephen KnappDocument12 paginiRamayana: A Summary by Stephen KnappRudy EsposoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sundara KandamDocument6 paginiSundara Kandamssrini2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Srimad Valmiki Ramayana (Sanskrit) 1933 ADDocument1.162 paginiSrimad Valmiki Ramayana (Sanskrit) 1933 ADAnkurNagpal108100% (2)

- Mangalacharan 7Document2 paginiMangalacharan 7Ram DasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 11 12Document16 paginiUnit 11 12Arosh100Încă nu există evaluări

- Soal Ujian Sekolah Bahasa Jawa 2020Document3 paginiSoal Ujian Sekolah Bahasa Jawa 2020Mrs. GinanjarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wayang Golek Slide DescriptionsDocument32 paginiWayang Golek Slide DescriptionsNina MihailaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7 Punarvasu: "Quiver of Arrows"Document5 pagini7 Punarvasu: "Quiver of Arrows"Ozy CanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hanuman KavachamDocument2 paginiHanuman KavachamKendd ErerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Child and Adolescent Literature Handout 2Document15 paginiChild and Adolescent Literature Handout 2angellingon.25Încă nu există evaluări

- Vdocuments - MX Hindu Baby Boy NamesDocument38 paginiVdocuments - MX Hindu Baby Boy NamesGOWTHAM CHANDRUÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Ramayana: A Telling of The Ancient Indian EpicDocument17 paginiThe Ramayana: A Telling of The Ancient Indian EpicAndoingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Readiness Test in Q3Document10 paginiReadiness Test in Q3Ace York AguilarÎncă nu există evaluări

- DR Zakir Naik and His Colleagues at The IRF Believe SoDocument4 paginiDR Zakir Naik and His Colleagues at The IRF Believe SoBhaskar KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh: Welcome To Birth City of Lord RamaDocument2 paginiAyodhya, Uttar Pradesh: Welcome To Birth City of Lord RamaAishwarya VasudevenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stotra - Hindupedia, The Hindu Encyclopedia PDFDocument22 paginiStotra - Hindupedia, The Hindu Encyclopedia PDFPallab Chakraborty100% (1)