Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Example Document

Încărcat de

Gathy BrayohDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Example Document

Încărcat de

Gathy BrayohDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

§10.

1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference

Between Two Sample Means for Independent Samples

Tom Lewis

Fall Term 2009

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for1 Indepe

/6

Outline

1 The rationale

2 A small example

3 Normal populations

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for2 Indepe

/6

The rationale

A typical problem

Do women do better on the SAT than men? How could we test for this?

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for3 Indepe

/6

The rationale

A typical problem

Do women do better on the SAT than men? How could we test for this?

There are two populations under consideration: the men and the

women.

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for3 Indepe

/6

The rationale

A typical problem

Do women do better on the SAT than men? How could we test for this?

There are two populations under consideration: the men and the

women.

There is a common statistic under consideration: the SAT score.

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for3 Indepe

/6

The rationale

A typical problem

Do women do better on the SAT than men? How could we test for this?

There are two populations under consideration: the men and the

women.

There is a common statistic under consideration: the SAT score.

Each population has its own population mean SAT score: µ1 for the

boys and µ2 for the girls.

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for3 Indepe

/6

The rationale

A typical problem

Do women do better on the SAT than men? How could we test for this?

There are two populations under consideration: the men and the

women.

There is a common statistic under consideration: the SAT score.

Each population has its own population mean SAT score: µ1 for the

boys and µ2 for the girls.

We can collect random samples from each population and compute

the sample means of their SAT scores: x 1 for the boys and x 2 for the

girls.

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for3 Indepe

/6

The rationale

A typical problem

Do women do better on the SAT than men? How could we test for this?

There are two populations under consideration: the men and the

women.

There is a common statistic under consideration: the SAT score.

Each population has its own population mean SAT score: µ1 for the

boys and µ2 for the girls.

We can collect random samples from each population and compute

the sample means of their SAT scores: x 1 for the boys and x 2 for the

girls.

How can we compare the sample means? How much of a difference

between the sample means, x 2 − x 1 , is sufficient to assert that there

is a difference in the population means, µ2 − µ1 .

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for3 Indepe

/6

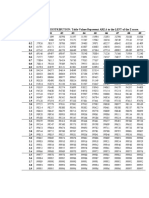

A small example

A small example

Here are the scores on a recent exam for a group of boys and girls:

Alex Bob Chuck Denise Ellen Fergie Gisele

55 75 68 82 76 88 50

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for4 Indepe

/6

A small example

A small example

Here are the scores on a recent exam for a group of boys and girls:

Alex Bob Chuck Denise Ellen Fergie Gisele

55 75 68 82 76 88 50

Find all samples of size 2 from the boys and all samples of size three

from the girls. Find the values of the mean of the scores for each of

the random samples. Let x 1 be the mean of the boy’s samples and let

x 2 denote the means of the girl’s samples.

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for4 Indepe

/6

A small example

A small example

Here are the scores on a recent exam for a group of boys and girls:

Alex Bob Chuck Denise Ellen Fergie Gisele

55 75 68 82 76 88 50

Find all samples of size 2 from the boys and all samples of size three

from the girls. Find the values of the mean of the scores for each of

the random samples. Let x 1 be the mean of the boy’s samples and let

x 2 denote the means of the girl’s samples.

Find all 12 possible values of x 1 − x 2 .

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for4 Indepe

/6

A small example

A small example

Here are the scores on a recent exam for a group of boys and girls:

Alex Bob Chuck Denise Ellen Fergie Gisele

55 75 68 82 76 88 50

Find all samples of size 2 from the boys and all samples of size three

from the girls. Find the values of the mean of the scores for each of

the random samples. Let x 1 be the mean of the boy’s samples and let

x 2 denote the means of the girl’s samples.

Find all 12 possible values of x 1 − x 2 .

Find the mean and standard deviation of the values of x 1 − x 2 .

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for4 Indepe

/6

Normal populations

Normal data

Our next result is significant, but it requires that the variable under

question be normally distributed within the two populations.

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for5 Indepe

/6

Normal populations

Normal data

Our next result is significant, but it requires that the variable under

question be normally distributed within the two populations.

Theorem

Suppose that x is a normally distributed variable on each of two

populations. Then, for independent samples of size n1 and n2 from the

two populations,

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for5 Indepe

/6

Normal populations

Normal data

Our next result is significant, but it requires that the variable under

question be normally distributed within the two populations.

Theorem

Suppose that x is a normally distributed variable on each of two

populations. Then, for independent samples of size n1 and n2 from the

two populations,

µx 1 −x 2 = µ1 − µ2 ,

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for5 Indepe

/6

Normal populations

Normal data

Our next result is significant, but it requires that the variable under

question be normally distributed within the two populations.

Theorem

Suppose that x is a normally distributed variable on each of two

populations. Then, for independent samples of size n1 and n2 from the

two populations,

µx 1 −x 2 = µ1 − µ2 ,

q

σx 1 −x 2 = (σ12 /n1 ) + (σ22 /n2 )

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for5 Indepe

/6

Normal populations

Normal data

Our next result is significant, but it requires that the variable under

question be normally distributed within the two populations.

Theorem

Suppose that x is a normally distributed variable on each of two

populations. Then, for independent samples of size n1 and n2 from the

two populations,

µx 1 −x 2 = µ1 − µ2 ,

q

σx 1 −x 2 = (σ12 /n1 ) + (σ22 /n2 )

x 1 − x 2 is normally distributed.

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for5 Indepe

/6

Normal populations

Problem

Work problems 10.10 and 10.18 from the text.

Tom Lewis () §10.1–The Sampling Distribution of the Difference Between Two

FallSample

Term 2009

Means for6 Indepe

/6

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- SamplingDocument66 paginiSamplingMerleAngeliM.SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Probability and Statistics Twelfth Edition: Presentation Designed and Written By: Barbara M. BeaverDocument31 paginiIntroduction To Probability and Statistics Twelfth Edition: Presentation Designed and Written By: Barbara M. BeaverRomesa KhalilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notes10 PDFDocument2 paginiNotes10 PDFyohanesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chap012 Analysis of VarianceDocument28 paginiChap012 Analysis of Variancejohn brownÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sampling and Sampling Distribution 2Document19 paginiSampling and Sampling Distribution 2cacayuanhermannaldredÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of Variance: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDocument40 paginiAnalysis of Variance: Mcgraw-Hill/Irwineusebio 97Încă nu există evaluări

- Roadmap For A Statistical InvestigationDocument2 paginiRoadmap For A Statistical InvestigationAbhishekKumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 09Document25 paginiChapter 09neltyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rubric and Guidelines For EUAL - Scenario and GP - 2023-2024Document7 paginiRubric and Guidelines For EUAL - Scenario and GP - 2023-2024zeddero19Încă nu există evaluări

- Hypothesis TestingDocument21 paginiHypothesis TestingjomwankundaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Two-Sample Tests of Hypothesis: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDocument38 paginiTwo-Sample Tests of Hypothesis: Mcgraw-Hill/Irwineusebio 97Încă nu există evaluări

- Ch07 Sampling Distribution PDFDocument17 paginiCh07 Sampling Distribution PDFAlexander CoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dynamic sampling boosts multi-task reading comprehensionDocument5 paginiDynamic sampling boosts multi-task reading comprehension刘中坤Încă nu există evaluări

- Sampling Methods and The Central Limit TheoremDocument30 paginiSampling Methods and The Central Limit TheoremNadia TanzeemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding the Central Limit TheoremDocument7 paginiUnderstanding the Central Limit TheoremRowel ElcaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Diagnostic Spelling Test - Sounds (DiSTs)Document9 paginiThe Diagnostic Spelling Test - Sounds (DiSTs)Anthony LaniganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 5-Chapt 4-Normal Distribution & SamplingDocument24 paginiLecture 5-Chapt 4-Normal Distribution & SamplingNgọc MinhÎncă nu există evaluări

- SBE - Lind 14 TH CH 06 Discrete Probability DistributionsDocument13 paginiSBE - Lind 14 TH CH 06 Discrete Probability DistributionsSiti Namira AisyahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sampling Distributions: Prem Mann, Introductory Statistics, 9/EDocument110 paginiSampling Distributions: Prem Mann, Introductory Statistics, 9/EAfrin NaharÎncă nu există evaluări

- 13 PDFDocument24 pagini13 PDFAditya MukherjeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- AP Statistics Ch 1 Test ReviewDocument5 paginiAP Statistics Ch 1 Test ReviewRubbie NguyenÎncă nu există evaluări

- CR Session1 SlideDocument25 paginiCR Session1 Slidebuitri84@yahoo.comÎncă nu există evaluări

- To Pool or Not To Pool: That Is The ConfusionDocument7 paginiTo Pool or Not To Pool: That Is The ConfusionMayssa BougherraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 6 - Sampling DistributionsDocument37 paginiModule 6 - Sampling DistributionsGhian Carlo Garcia CalibuyotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stat Chap012 - 2 KPPDocument18 paginiStat Chap012 - 2 KPPTrina IslamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Two-Sample Tests of Hypothesis: ©the Mcgraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2008 Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDocument38 paginiTwo-Sample Tests of Hypothesis: ©the Mcgraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 2008 Mcgraw-Hill/Irwiniracahyaning tyasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discussion 1 For Statistics STA 013Document3 paginiDiscussion 1 For Statistics STA 013Sanya RemiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discrete Probability Distributions: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDocument15 paginiDiscrete Probability Distributions: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinImam AwaluddinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Caema6 - Set eDocument16 paginiCaema6 - Set efa.shaberayasminÎncă nu există evaluări

- CH 07Document107 paginiCH 07Mohsen AyyashÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter - 04 - Probability and Probability DistributionDocument117 paginiChapter - 04 - Probability and Probability DistributionFardin Selim KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- BSAFC4 - PPT - ch10 (Two Sample Test) v2 (1) - CompressedDocument96 paginiBSAFC4 - PPT - ch10 (Two Sample Test) v2 (1) - CompressedwiamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bsafc4 PPT Ch10 (Anova) - CompressedDocument87 paginiBsafc4 PPT Ch10 (Anova) - CompressedwiamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of Variance: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDocument33 paginiAnalysis of Variance: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinTauhid Ahmed BappyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week 4 Chap012 ANOVADocument33 paginiWeek 4 Chap012 ANOVAshineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Probability and Statistics Twelfth EditionDocument47 paginiIntroduction To Probability and Statistics Twelfth EditionKhalid Bin waleedÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 - Analyze - Inferential StatisticsDocument29 pagini3 - Analyze - Inferential StatisticsParaschivescu CristinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Normal Distribution 2Document23 paginiThe Normal Distribution 2Ellemarej AtanihÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ask Me AnythingDocument59 paginiAsk Me AnythingAnna Giralt GrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stat Slides ch07Document104 paginiStat Slides ch07Akib xabedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 22: Using Sample Data To Compare The Means of Two or More PopulationsDocument9 paginiLesson 22: Using Sample Data To Compare The Means of Two or More Populationsdrecosh-1Încă nu există evaluări

- Ias and Airness: Train/Test MismatchDocument12 paginiIas and Airness: Train/Test MismatchJiahong HeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 05Document29 paginiChapter 05Lucas LutherÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teorema de Limite CentralDocument32 paginiTeorema de Limite CentralFabiola BastidasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sampling Methods and The Central Limit Theorem: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDocument31 paginiSampling Methods and The Central Limit Theorem: Mcgraw-Hill/Irwineusebio 97Încă nu există evaluări

- Leiter 3 Manual Corrections UpdatesDocument10 paginiLeiter 3 Manual Corrections UpdatesDidenko MarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Handout 6: Sampling Methods and The Central Limit TheoremDocument15 paginiHandout 6: Sampling Methods and The Central Limit TheoremGlacier RamkissoonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practical 2 and 3 memoDocument11 paginiPractical 2 and 3 memomabotjasefudiÎncă nu există evaluări

- IPPTCh 008Document30 paginiIPPTCh 008Jacquelynne SjostromÎncă nu există evaluări

- Data Collection and SamplingDocument20 paginiData Collection and SamplingimtiazquaziÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chap012 Anova (ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE)Document41 paginiChap012 Anova (ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE)Syarifah Rifka AlydrusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Penguian Hip Dua Pihak Kul 7Document52 paginiPenguian Hip Dua Pihak Kul 7khairanimiftahÎncă nu există evaluări

- CH 07Document99 paginiCH 07Sabbir AhamedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Walpole Chapter 01Document12 paginiWalpole Chapter 01Fitri Andri Astuti100% (1)

- Paired T TestDocument24 paginiPaired T TestpriyankaswaminathanÎncă nu există evaluări

- ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE: TESTING MEAN AND VARIANCE DIFFERENCESDocument4 paginiANALYSIS OF VARIANCE: TESTING MEAN AND VARIANCE DIFFERENCESPoonam NaiduÎncă nu există evaluări

- Propensity Score Matching Maximizes Comparability for Program EvaluationDocument164 paginiPropensity Score Matching Maximizes Comparability for Program EvaluationMadam CashÎncă nu există evaluări

- IPPTCh 008Document49 paginiIPPTCh 00811Încă nu există evaluări

- JMP Start Statistics: A Guide to Statistics and Data Analysis Using JMP, Sixth EditionDe la EverandJMP Start Statistics: A Guide to Statistics and Data Analysis Using JMP, Sixth EditionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design and Implementation of Chopper-Stabilized AmplifiersDocument2 paginiDesign and Implementation of Chopper-Stabilized AmplifiersGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- .MX Claroline Backends DownloadDocument4 pagini.MX Claroline Backends DownloadHeriberto EspinosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cpa 296552 PDFDocument2 paginiCpa 296552 PDFGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zeros and Poles Transfer FunctionsDocument158 paginiZeros and Poles Transfer FunctionsGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- MTDC REFsDocument8 paginiMTDC REFsGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mathhw9 SolnDocument2 paginiMathhw9 SolnGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wave Guides Summary and ProblemsDocument11 paginiWave Guides Summary and ProblemsGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- E1asoln Ece302 sp06Document8 paginiE1asoln Ece302 sp06Gathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- 451 Exercise451 - Rev - S18Document2 pagini451 Exercise451 - Rev - S18Gathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Machine Copy For Proofreading, Vol. X, Y-Z, 2004Document23 paginiMachine Copy For Proofreading, Vol. X, Y-Z, 2004Gathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- SpaceDocument3 paginiSpaceGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Finance Department Finance InternDocument1 paginăFinance Department Finance InternGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- C13 1 CovDocument3 paginiC13 1 CovGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- .MX Claroline Backends DownloadDocument4 pagini.MX Claroline Backends DownloadHeriberto EspinosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sboa 212 ADocument5 paginiSboa 212 AGathy Brayoh100% (1)

- K. Cheng,: Is ofDocument2 paginiK. Cheng,: Is ofGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Course Structure Diploma in ITDocument1 paginăCourse Structure Diploma in ITGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statement: Google AdwordsDocument2 paginiStatement: Google AdwordsGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Induction Motor Chapter: Stator Resistance, Speed, Torque CalculationsDocument5 paginiInduction Motor Chapter: Stator Resistance, Speed, Torque CalculationsGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- ELG3311: Assignment 3: Problem 6-12Document15 paginiELG3311: Assignment 3: Problem 6-12Gathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Distortionless Transmission Line TheoryDocument7 paginiDistortionless Transmission Line TheoryGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Web Development Quotation: What About It?Document4 paginiWeb Development Quotation: What About It?Gathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- CCC502 Course OutlineDocument3 paginiCCC502 Course OutlineGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- TLDocument16 paginiTLMannanHarshaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Audience Data: Age and Gender SplitDocument23 paginiAudience Data: Age and Gender SplitGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- C13 1 CovDocument3 paginiC13 1 CovGathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4th Year Control Lab 1Document3 pagini4th Year Control Lab 1Gathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lab 1Document26 paginiLab 1Gathy BrayohÎncă nu există evaluări

- VSD Pumps Best PracticeDocument48 paginiVSD Pumps Best PracticebeechyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Confidence Intervals Survey ResultsDocument3 paginiConfidence Intervals Survey ResultsSantosh JhansiÎncă nu există evaluări

- chp2 EconometricDocument54 paginichp2 EconometricCabdilaahi CabdiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ketentuan Efek Mediasi Dalam Structural Equation ModelDocument3 paginiKetentuan Efek Mediasi Dalam Structural Equation ModelWahyu AlchalidyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Value Relevance of Accounting InformationDocument10 paginiValue Relevance of Accounting InformationmimriyathÎncă nu există evaluări

- StandardnormaltableDocument1 paginăStandardnormaltableMax LedererÎncă nu există evaluări

- Determinan Kejadian Anak Balita Di Bawah Garis Merah Di Puskesmas Awal TerusanDocument16 paginiDeterminan Kejadian Anak Balita Di Bawah Garis Merah Di Puskesmas Awal TerusanPratiwi Abd.KarimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statistics Assignment of B.A Psychology IGNOUDocument9 paginiStatistics Assignment of B.A Psychology IGNOUSyed AhmadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artikel SkripsiDocument7 paginiArtikel SkripsiWuri AstiwiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercise 3Document2 paginiExercise 3drive quintoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Methods For The Behavioral Sciences 6Th Edition Gravetter Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument34 paginiResearch Methods For The Behavioral Sciences 6Th Edition Gravetter Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFJeffreyWalkerfpqrm100% (8)

- Lampiran 5 Hasil Analisis SPSS 20 1. Karakteristik RespondenDocument4 paginiLampiran 5 Hasil Analisis SPSS 20 1. Karakteristik RespondenIfan TaufanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter Three MultipleDocument15 paginiChapter Three MultipleabdihalimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inferential Statistics (AutoRecovered)Document12 paginiInferential Statistics (AutoRecovered)Shariq AnsariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Overfitting and Solution SovlveDocument3 paginiOverfitting and Solution SovlveLoc TranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning Activity SheetDocument6 paginiLearning Activity SheetPOTENCIANO JR TUNAYÎncă nu există evaluări

- 21st Century .PDF Efikasi, TeknologiDocument11 pagini21st Century .PDF Efikasi, TeknologiSumathy RamasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Digital Notes on Probability & StatisticsDocument200 paginiDigital Notes on Probability & StatisticsLingannaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Two-Way ANOVA StudyDocument4 paginiTwo-Way ANOVA StudyM.nour El-dinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statistics Methods for Economics - 20 MarksDocument3 paginiStatistics Methods for Economics - 20 MarksShruti Halder100% (2)

- Descriptive Statistics ToolsDocument21 paginiDescriptive Statistics Toolsvisual3d0% (1)

- Measures of Central LocationDocument17 paginiMeasures of Central LocationkaryawanenkaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Types of Probability Sampling TechniquesDocument9 paginiTypes of Probability Sampling TechniquesFinreese LoiseÎncă nu există evaluări

- 8 - Analyze - Hypothesis Testing Non Normal Data - P2Document37 pagini8 - Analyze - Hypothesis Testing Non Normal Data - P2Paraschivescu CristinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- RDocument33 paginiRShrutika AgrawalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Care GiverDocument9 paginiCare GiverindahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of Proficiency Test Data by Different Statistical Methods ComparisonDocument10 paginiEvaluation of Proficiency Test Data by Different Statistical Methods Comparisonbiologyipbcc100% (1)

- QM2 Stat Chap 14 Comparing Two MeansDocument2 paginiQM2 Stat Chap 14 Comparing Two MeansJeanne OllaÎncă nu există evaluări

- SOWQMT1014JD11Document5 paginiSOWQMT1014JD11Zarina Binti Mohd KhalidÎncă nu există evaluări

- GRADISTAT-1 (Danau)Document222 paginiGRADISTAT-1 (Danau)AndryTiraskaÎncă nu există evaluări