Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

00b6 PDF

Încărcat de

Tu SuTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

00b6 PDF

Încărcat de

Tu SuDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Human Resource Development Review

http://hrd.sagepub.com

Knowledge Sharing in Organizations: A Conceptual Framework

Minu Ipe

Human Resource Development Review 2003; 2; 337

DOI: 10.1177/1534484303257985

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://hrd.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/2/4/337

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Academy of Human Resource Development

Additional services and information for Human Resource Development Review can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://hrd.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://hrd.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations (this article cites 42 articles hosted on the

SAGE Journals Online and HighWire Press platforms):

http://hrd.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/2/4/337

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Theory and Conceptual Article

10.1177/1534484303257985

Human Resource Development Review / December 2003

Ipe / KNOWLEDGE SHARING

ARTICLE

Knowledge Sharing in Organizations:

A Conceptual Framework

MINU IPE

University of Minnesota

Knowledge is now being seen as the most important strategic resource in

organizations, and the management of this knowledge is considered criti-

cal to organizational success. If organizations have to capitalize on the

knowledge they possess, they have to understand how knowledge is cre-

ated, shared, and used within the organization. Knowledge exists and is

shared at different levels in organizations. This article examines knowl-

edge sharing at the most basic level; namely, between individuals in orga-

nizations. Based on a review of existing literature in this area, this article

presents a model that identifies factors that most significantly influence

knowledge sharing at this level.

Keywords: knowledge; knowledge sharing; knowledge transfer; knowl-

edge sharing between individuals

In recent years, the concept of knowledge in organizations has become

increasingly popular in the literature (Alvesson & Karreman, 2001), with

knowledge being recognized as the most important resource of organi-

zations (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; Spender & Grant, 1996). Although

knowledge has always been an important factor in organizations, only in the

last decade has it been considered the primary source of competitive advan-

tage (Stewart, 1997) and critical to the long-term sustainability and success

of organizations (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). The recognition of knowledge

as the key resource of today’s organizations affirms the need for processes

that facilitate the creation, sharing, and leveraging of individual and collec-

tive knowledge (Becerra-Fernandez & Sabherwal, 2001; Drucker, 1993).

More and more organizations are attempting to set up knowledge manage-

ment systems and practices to more effectively use the knowledge they

have, and numerous publications have discussed the importance of knowl-

edge in organizations. Even so, there is much to be learned and understood

about how knowledge is created, shared, and used in organizations (Grover

& Davenport, 2001; Tsoukas & Vladimirou, 2001).

Human Resource Development Review Vol. 2, No. 4 December 2003 337-359

DOI: 10.1177/1534484303257985

© 2003 Sage Publications

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

338 Human Resource Development Review / December 2003

The purpose of this article is to contribute to a better understanding of the

phenomenon of knowledge sharing between individuals in organizations.

Drawing on literature from several fields of study, a model of knowledge

sharing between individuals in organizations is developed. Although

knowledge exists at many levels in organizations, the focus of this article is

the knowledge that exists with and within individuals and the factors that

influence the process of knowledge sharing between individuals.

The field of knowledge management has traditionally been dominated by

information technology and technology-driven perspectives (Davenport,

De Long, & Beers, 1998; Gourlay, 2001). However, there is increasing rec-

ognition of the role of individuals in knowledge management processes and

a growing interest in the “people perspective” of knowledge in organi-

zations (Earl, 2001; Stenmark, 2001). The key to successfully managing

knowledge is now being seen as dependent on the connections between indi-

viduals within the organization (Brown & Duguid, 1991; McDermott,

1999). Increasing empirical evidence also points to the importance of peo-

ple and people-related factors as critical to knowledge processes within

organizations (e.g., Andrews & Delahaye, 2000; Quinn, Anderson, &

Finkelstein, 1996).

At the heart of the people perspective of knowledge management is the

notion that individuals in organizations have knowledge (Spender & Grant,

1996) that must move to the level of groups and the organization as a whole

so that it can be used to advance the goals of the organization (Nonaka,

1994). There is growing realization that knowledge sharing is critical to

knowledge creation, organizational learning, and performance achievement

(Bartol & Srivastava, 2002). Individuals in organizations have always cre-

ated and shared knowledge and therefore knowledge sharing was consid-

ered to be a natural function of workplaces, an activity that took place auto-

matically (Chakravarthy, Zaheer, & Zaheer, 1999). Yet it is now being

acknowledged that even under the best of circumstances, knowledge shar-

ing within organizations is a multifaceted, complex process (Hendriks,

1999; Lessard & Zaheer, 1996).

Method

A variety of fields have reported on the concept of knowledge and knowl-

edge sharing in organizations. The conceptual framework presented in this

article has drawn on literature from fields such as management theory, stra-

tegic management, information and decision sciences, organizational com-

munication, and organizational behavior. These fields of study were identi-

fied through a search of scholarly literature available primarily through

electronic databases. The initial review of literature began with an examina-

tion of publications that discussed the concept of knowledge and how this

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Ipe / KNOWLEDGE SHARING 339

knowledge existed within organizations. The review process was then nar-

rowed down to publications that referred specifically to the movement of

knowledge within organizations. Some of the key concepts considered dur-

ing the review included knowledge sharing, knowledge transfer, knowledge

creation, knowledge acquisition, individual and organizational learning,

and information distribution and dissemination.

The initial broad review of relevant literature was followed by the pro-

cess of analysis and synthesis. Analysis of literature began with identifying

publications that were relevant to this article, those that addressed issues

related to individual knowledge in organizations and how individuals

shared their knowledge with others within their work settings. Once rele-

vant publications were identified, the focus of the analysis shifted to iso-

lating those ideas that specifically related to knowledge sharing between

individuals. Specific attention was given to identifying common themes

among the various sources during this process.

The key factors related to knowledge sharing that emerged from the liter-

ature were then synthesized to form the conceptual framework presented in

this article. The process of synthesis focused on capturing the dominant

ideas related to knowledge sharing as it exists at this point in time. The

review of literature revealed important ideas generated by several fields of

study pertaining to knowledge and knowledge sharing in organizations. The

conceptual framework presented in this article is an attempt to bring

together all these ideas into one whole to provide a more comprehensive

approach to understanding the phenomenon of knowledge sharing within

organizations. The framework also proposes relationships between the dif-

ferent factors identified from the literature. Some of these relationships are

apparent in the literature, whereas others are being proposed in this article to

further explore the interaction between the primary factors that influence

knowledge sharing in organizational settings. These relationships are dis-

cussed in detail later in the article.

Knowledge in Organizations

Although there is much written about why managing knowledge is

important to organizations, there is considerably less on the how—the pro-

cesses that are used to identify, capture, share, and use knowledge within

organizations. Knowledge in organizational settings tends to be fuzzy in

nature and closely attached to the individuals who hold it (Davenport et al.,

1998), challenging efforts to define, measure, and manage it. Knowledge

can also be subject to multiple classifications and can have several mean-

ings. A comprehensive review of the various classifications of knowledge is

beyond the scope of this article. Some useful categorizations may be found

in Blackler (1995) and Venzin, von Krogh, and Roos (1998).

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

340 Human Resource Development Review / December 2003

The terms information and knowledge are often used interchangeably in

the literature. Some authors distinguished between the two terms (e.g.,

Blackler, 1995; Davenport & Prusak, 1998; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995;

Pemberton, 1998), whereas others used both terms synonymously (e.g.,

Kogut & Zander, 1992; Stewart, 1997). This article recognizes the distinc-

tion between information and knowledge.

Davenport and Prusak (1998) defined knowledge as “a fluid mix of

framed experience, values, contextual information, and expert insights that

provides a framework for evaluating and incorporating new experiences and

information. It originates in and is applied in the minds of knowers” (p. 5).

Nonaka and Takeuchi’s (1995) definition of knowledge is far broader in

scope and is stated as “a dynamic human process of justifying personal

belief toward the truth” (p. 58). According to these authors, information is

the “flow of messages” (p. 58), and knowledge is created when this flow of

messages interacts with the beliefs and commitments of its holders. They

identified three characteristics that distinguished information from knowl-

edge. First, knowledge is a function of a particular perspective, intention, or

stance taken by individuals, and therefore, unlike information, it is about

beliefs and commitment. Second, knowledge is always about some end,

which means that knowledge is about action. Third, it is context specific and

relational and therefore it is about meaning.

Individual Knowledge in Organizations

Knowledge exists at multiple levels within organizations. De Long and

Fahey (2000) divided it into individual, group, and organizational levels.

Roos and von Krogh (1992) added the levels of departments and divisions.

This article focuses on the most basic of these levels, the knowledge that is

possessed by individuals. Although individuals constitute only one level at

which knowledge resides within organizations, the sharing of individual

knowledge is imperative to the creation, dissemination, and management of

knowledge at all the other levels within an organization.

Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995), in their definitive work The Knowledge

Creating Company, were among the first to recognize the importance of

individual employees in the knowledge creation process. According to

them, knowledge creation should be viewed as a process whereby knowl-

edge held by individuals is amplified and internalized as part of an organi-

zation’s knowledge base. Thus, knowledge is created through interaction

between individuals at various levels in the organization. Nonaka and

Takeuchi argued that organizations cannot create knowledge without indi-

viduals, and unless individual knowledge is shared with other individuals

and groups, the knowledge is likely to have limited impact on organizational

effectiveness.

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Ipe / KNOWLEDGE SHARING 341

Lam (2000) defined individual knowledge as “that part of an organiza-

tion’s knowledge which resides in the brains and bodily skills of the individ-

ual” (p. 491). It involves all the knowledge possessed by the individual that

can be applied independently to specific types of tasks and problems.

Because individuals have cognitive limits in terms of storing and processing

information, individual knowledge tends to be specialized and domain-

specific in nature (Lam, 2000). Literature from the area of organizational

learning also contributes to the notion that knowledge in organizations

resides within individuals. Simon (1991) emphasized the role of individuals

in the knowledge process by stating that “all organizational learning takes

place inside human heads” (p. 176). Argyris (1990) reinforced this point of

view by suggesting that organizations learn through individuals and this

individual learning is facilitated or inhibited by factors within the organiza-

tional learning system. Huber (1991) further argued that knowledge could

only reside at the individual level because cognition is a function of individ-

uals that cannot be performed by organizations.

At the individual level, Lowendahl, Revang, and Fosstenlokken (2001)

identified three types of knowledge that are important to value creation in

organizations—know-how, know-what, and dispositional knowledge.

Know-how included experienced-based knowledge that is subjective and

tacit, and know-what included task-related knowledge that is objective in

nature. Dispositional knowledge was defined as personal knowledge that

included talents, aptitude, and abilities. Tsoukas and Vladimirou (2001)

further emphasized the role of individuals in the creation and sharing of

knowledge, while Polanyi (1966) insisted that all knowledge is essentially

personal in nature. Others who suggested that knowledge in organizations is

found at the level of individuals include Alvesson (1995), Brown and Wood-

land (1999), Gupta and Govindarajan (2000), Nonaka (1994), Staples and

Jarvenpaa (2001), and Weiss (1999).

Knowledge Sharing in Organizations

An organization’s ability to effectively leverage its knowledge is highly

dependent on its people, who actually create, share, and use the knowledge.

Leveraging knowledge is only possible when people can share the knowl-

edge they have and build on the knowledge of others. Knowledge sharing is

basically the act of making knowledge available to others within the orga-

nization. Knowledge sharing between individuals is the process by which

knowledge held by an individual is converted into a form that can be under-

stood, absorbed, and used by other individuals. The use of the term sharing

implies that this process of presenting individual knowledge in form that

can be used by others involves some conscious action on the part of the indi-

vidual who possesses the knowledge. Sharing also implies that the sender

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

342 Human Resource Development Review / December 2003

does not relinquish ownership of the knowledge; instead, it results in joint

ownership of the knowledge between the sender and the recipient.

Davenport (1997) defined sharing as a voluntary act and distinguished it

from reporting. Reporting involves the exchange of information based on

some routines or structured formats. Sharing, on the other hand, implies a

conscious act by an individual who participates in the knowledge exchange

even though there is no compulsion to do so. Hendriks (1999) suggested that

knowledge sharing implies a relationship between at least two parties—one

that possesses the knowledge and the other that acquires the knowledge.

This article makes a distinction between knowledge sharing between indi-

viduals and the concept of knowledge transfer used predominantly to

describe the movement of knowledge between larger entities within organi-

zations, such as between departments or divisions and between organiza-

tions themselves (e.g., Chakravarthy et al., 1999; Lam, 1997).

Knowledge sharing is important because it provides a link between the

individual and the organization by moving knowledge that resides with indi-

viduals to the organizational level, where it is converted into economic and

competitive value for the organization (Hendriks, 1999). Cohen and

Levinthal (1990) proposed that interactions between individuals who pos-

sess diverse and different knowledge enhance the organization’s ability to

innovate far beyond what any one individual can achieve. Boland and

Tenkasi (1995) concurred with this idea and contended that competitive

advantage and product success in organizations results from individuals

with diverse knowledge collaborating synergistically toward common out-

comes. According to these authors, the creation of an organization’s knowl-

edge base requires “a process of mutual perspective taking where distinctive

individual knowledge is exchanged, evaluated, and integrated with that of

others in the organization” (p. 358). Knowledge sharing also leads to the

dissemination of innovative ideas and is considered critical to creativity and

subsequent innovation in organizations (Armbrecht, Chapas, Chappelow, &

Farris, 2001). However, in practice, the lack of knowledge sharing has

proved to be a major barrier to the effective management of knowledge in

organizations (Davenport & Prusak, 1998; Hendriks, 1999).

Knowledge sharing between individuals is a process that contributes to

both individual and organizational learning (Andrews & Delahaye, 2000;

Nidumolu, Subramani, & Aldrich, 2001). Organizational knowledge is rec-

ognized as a key component of organizational learning (Dodgson, 1993;

Huber, 1991). Huber (1991) further identified four knowledge concepts that

contribute to organizational learning—knowledge acquisition, information

distribution, information interpretation, and organizational memory. The

concept of knowledge sharing as it is presented in this article is linked to

both knowledge distribution and knowledge acquisition. The voluntary act

of sharing knowledge by an individual contributes to knowledge distribu-

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Ipe / KNOWLEDGE SHARING 343

tion, and the process of sharing may result in knowledge acquisition by

other individuals within the organization. Knowledge sharing between indi-

viduals thus results in individual learning, which in turn may contribute to

organizational learning.

Knowledge management calls for managing organizational knowledge

as a corporate asset and harnessing knowledge creation and sharing as key

organizational capabilities (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). A possible concern

in this approach to managing knowledge is that much of organizational

knowledge is controlled at the level of individuals (Staples & Jarvenpaa,

2001). Individuals use the knowledge they have in their daily activities at

work (Lam, 2000), and unless the organization can facilitate the sharing of

this knowledge with others, it is likely to lose this knowledge when individ-

ual employees leave (Gupta & Govindarajan, 2000). Even if individuals

stay with the organization, the full extent of their knowledge may not be

realized and utilized unless there are opportunities for the individual to

share that knowledge with others in the organization (Weiss, 1999).

Understanding the process of knowledge sharing between individuals is

one step toward a better understanding of knowledge sharing as a whole in

organizations. The following section elaborates on the factors identified

from literature that influence knowledge sharing between individuals in

organizations.

Factors That Influence Knowledge Sharing

There is a paucity of research specifically in the area of knowledge shar-

ing between individuals in organizations, and empirical evidence has just

begun to uncover some of the complex dynamics that exist in processes

related to knowledge sharing. Based on a review of theory and research

related to knowledge sharing, the following have been identified as the

major factors that influence knowledge sharing between individuals in

organizations: the nature of knowledge, motivation to share, opportunities

to share, and the culture of the work environment.

Nature of Knowledge

Knowledge by its very nature exists in both tacit and explicit forms. How-

ever, with the increasing recognition of the importance of knowledge in

organizations, different types of knowledge have also begun to be valued

differently within organizations. These two characteristics of the nature of

knowledge, tacitness and explicitness of knowledge, and the value attrib-

uted to knowledge have a significant influence on the way knowledge is

shared within organizations.

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

344 Human Resource Development Review / December 2003

Tacit and explicit knowledge. The dominant classification of knowledge in

organizations divides it into two types, tacit and explicit. The critical differ-

ences between these two types are found in three major areas—codifiability

and mechanisms for transfer, methods for acquisition and accumulation, and

the potential to be collected and distributed (Lam, 2000). The concept of tacit

knowledge was first presented by Polanyi (1966), who argued that a large part

of human knowledge cannot be articulated and made explicit easily. Tacit

knowledge can be thought of as the know-how that is acquired through personal

experience (Nonaka, 1994). It is therefore not easily codifiable and cannot be

communicated or used without the individual who is the knower. Tacit knowl-

edge also tends to be sticky in nature. von Hippel (1994) defined stickiness as

the incremental expenditure involved in moving knowledge in a form that is

useable and easily understood by the information seeker. According to von

Hippel, stickiness for the knowledge supplier comes from the tacitness of the

knowledge that has to be shared, whereas absorptive capacity creates stickiness

for the knowledge user. Therefore, tacitness of knowledge is a natural impedi-

ment to the successful sharing of knowledge between individuals in

organizations.

Explicit knowledge, on the other hand, can be easily codified, stored at a

single location, and transferred across time and space independent of indi-

viduals (Lam, 2000). It is easier to disseminate and communicate (Schulz,

2001). Explicit knowledge therefore has a natural advantage over tacit

knowledge in terms of its ability to be shared relatively easily among indi-

viduals. However, just because explicit knowledge is easily transferred

across individuals and settings, it should not be assumed that it is easily

shared in organizations. Weiss (1999) argued that the ability to articulate

knowledge should not be equated with its availability for use by others in the

organization. To support this point, he made a distinction between explicit

knowledge that is easily shared with that which is not by introducing the

notion of rationalized knowledge and embedded knowledge within the con-

text of professional services organizations. Rationalized knowledge is gen-

eral, context independent, standardized, and public (e.g., methodologies for

conducting consulting projects). Weiss suggested that because this knowl-

edge has been separated from its original source and is independent of spe-

cific individuals, this knowledge is readily shared and available to all those

who seek it. Embedded knowledge, on the other hand, is context dependent,

narrowly applicable, personalized, and may be personally or professionally

sensitive. Therefore, explicit knowledge that is embedded in nature is not

likely to be easily shared among individuals. However, knowledge must be

seen as more than just explicit and tacit in nature. Regardless of whether

knowledge is tacit or explicit, the value attributed to it also has a significant

impact on whether and how individuals share it.

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Ipe / KNOWLEDGE SHARING 345

Value of knowledge. Knowledge is increasingly perceived as being com-

mercially valuable, and its ownership is being recognized by both individuals

and the organizations they work in (Brown & Woodland, 1999; Staples &

Jarvenpaa, 2001; Weiss, 1999). When individuals perceive the knowledge they

possess as a valuable commodity, knowledge sharing becomes a process medi-

ated by decisions about what knowledge to share, when to share, and who to

share it with (Andrews & Delahaye, 2000). In situations in which it is valued

highly, individuals may tend to claim emotional ownership of knowledge

(Jones & Jordan, 1998). This sense of ownership comes from the fact that in

several settings, individual knowledge is linked to status, career prospects, and

individual reputations (Andrews & Delahaye, 2000). The sharing of such

knowledge is a complex process, and Jones and Jordan (1998) found that it

involved, among other things, the extent to which individuals perceived them-

selves to be valued by their organization.

Certain types of knowledge are valued highly by both individuals and

organizations. For example, knowledge related to research and develop-

ment (R&D) is valued highly because of its commercial and scientific value.

Research suggests that in R&D organizations, creative power resides in a

relatively small number of individuals (Armbrecht et al., 2001), creating

issues of ownership particularly because it is linked to tangible outcomes

such as creation of new products, patents, research grants, and individual

incomes. Therefore, in highly competitive environments or those in which

knowledge has high commercial value, there exists a dilemma resulting

from contradictory incentives to share knowledge and to withhold it.

In organizations in which an individual’s knowledge becomes his or her

primary source of value to the firm, sharing this knowledge might poten-

tially result in diminishing the value of the individual, creating a reluctance

to engage in knowledge-sharing activities (Alvesson, 1993; Empson, 2001).

Professionals, in particular, tend to guard their knowledge as they perceive

that their own value to the firm is a product of the knowledge they possess

(Weiss, 1999). Any reluctance to share knowledge is further heightened in

situations characterized by uncertainties and insecurities, such as mergers

(Empson, 2001) and acquisitions.

Motivation to Share

Knowledge is “intimately and inextricably bound with people’s egos and

occupations” and does not flow easily across the organization (Davenport

et al., 1998, p. 45). According to Stenmark (2001), people are not likely to

share knowledge without strong personal motivation. Motivational factors

that influence knowledge sharing between individuals can be divided into

internal and external factors. Internal factors include the perceived power

attached to the knowledge and the reciprocity that results from sharing.

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

346 Human Resource Development Review / December 2003

External factors include relationship with the recipient and rewards for

sharing.

Knowledge as power. The increasing importance given to knowledge in

organizations, and the increasing value attributed to individuals who possess

the right kind of knowledge are conducive to creating the notion of power

around knowledge. If individuals perceive that power comes from the knowl-

edge they possess, it is likely to lead to knowledge hoarding instead of knowl-

edge sharing (Davenport, 1997; Gupta & Govindarajan, 2000). According to

Brown and Woodland (1999), individuals use knowledge for both control and

defense. In a competitive environment, withholding knowledge from those

considered competitors is often regarded as being useful to attaining one’s

goals (Pfeffer, 1980). Power politics is therefore an important aspect of knowl-

edge sharing in organizations (Weiss, 1999).

In a study of knowledge management initiatives in more than 25 compa-

nies over a period of 2 years, Davenport, Eccles, and Prusak (1992) found

that the primary reason these initiatives did not succeed was because these

organizations did not manage what the authors labeled “the politics of infor-

mation” (p. 53). Blackler, Crump, and McDonald (1998) concurred with the

notion that knowledge can be perceived as a source of power in organiza-

tions. They suggested that because knowledge is always situated within a

particular context, it is natural that culture and power dynamics within the

context affect the way knowledge is perceived and used.

Reciprocity. Reciprocity, or the mutual give-and-take of knowledge can

facilitate knowledge sharing if individuals see that the value-add to them

depends on the extent to which they share their own knowledge with others

(Hendriks, 1999; Weiss, 1999). Molm, Takahashi, and Peterson (2000) defined

reciprocal acts as those in which individuals help others and share information

“without negotiation of terms and without knowledge of whether or when the

other will reciprocate” (p. 1396). Reciprocity as a motivator of knowledge shar-

ing implies that individuals must be able to anticipate that sharing knowledge

will prove worthwhile (Schultz, 2001), even if they are uncertain about exactly

what the outcome will be (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). It is the expectation that

those involved in sharing knowledge will be able to acquire or benefit from

some of the value created by their involvement.

Empirical evidence for the relationship between reciprocity and knowl-

edge sharing indicates that receiving knowledge from others stimulates a

reciprocal flow of knowledge in the direction of the sender both horizontally

and vertically in organizations (Schulz, 2001). Support for the relationship

between reciprocity and knowledge sharing was also found by Hall (2001)

and Dyer and Nobeoka (2000). Reciprocity is also thought to be a motivator

of knowledge sharing in communities of practice where knowledge sharing

results in enhancing participants’ expertise and providing opportunities for

recognition (Bartol & Srivastava, 2002; Orr, 1990).

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Ipe / KNOWLEDGE SHARING 347

A negative aspect of reciprocity is the fear of exploitation, which was

found to be a serious threat to knowledge sharing between individuals

(Empson, 2001). Fear of exploitation is a reflection of extreme anxiety that

individuals experience when they perceive that they are being asked to give

away valuable knowledge with very little or no benefit to them in return.

Relationship with recipient. One of the external factors that influence the

motivation to share knowledge is the relationship between the sender and the

recipient. Relationship with the recipient includes two critical elements: (a)

trust and (b) the power and status of the recipient. According to Ghoshal and

Bartlett (1994), trust is one of four primary dimensions in organizations influ-

encing the actions of individuals. Huemer, von Krogh, and Roos (1998) further

argued that even though the distribution of power matters in organizations, trust

is more important as trust facilitates learning, and decisions to exchange knowl-

edge under certain conditions are based on trust.

In writing about knowledge communities (“groups or organizations

whose primary purpose is the development and promulgation of collective

knowledge”), Kramer (1999, p. 163) referred to trust as being a critical fac-

tor that influenced the way knowledge was shared within these communi-

ties. According to Kramer, barriers to trust rise from perceptions that others

are not contributing equally to the community or that others might exploit

their own cooperative efforts. These doubts and suspicions create a reluc-

tance to initiate exchanges with others or respond to others’ invitations to

participate in cooperative exchanges with members of the community.

The importance of perceived trustworthiness to knowledge sharing in

organizations was further reinforced by Andrews and Delahaye (2000) who

found that the role of trust was central to the way knowledge was shared by

individuals. Their study established that in the absence of trust, formal

knowledge-sharing practices were insufficient to encourage individuals to

share knowledge with others within the same work environment. Environ-

ments that are highly competitive are even more likely to have problems

with knowledge sharing that arise out of trust-related issues. Others who

stressed the importance of trust in knowledge sharing include Read (1962),

Roberts (2000), and Zand (1972).

Another aspect of the relationship with knowledge recipients points to

the power and status of the knowledge sharer vis-à-vis the knowledge recip-

ient. Issues of power that mediate the relationships between individuals

involved in such exchanges influence to some extent whether and how

knowledge is shared (Krone, Jablin, & Putnam, 1987; O’Reilly, 1978). In

his analysis of organizational information processing, Huber (1982) stated

that (a) individuals with low status and power in the organization tend to

direct information to those with more status and power, and (b) individuals

with more status and power tend to direct information more toward their

peers than toward those with low status and power. These findings find sup-

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

348 Human Resource Development Review / December 2003

port in research done by Allen and Cohen (1969) and Barnlund and Harland

(1963). Empirical evidence also indicates that individuals tend to screen

information that is passed upward in organizations, withholding or refrain-

ing from sharing information that would be unfavorable to the communica-

tor (O’Reilly, 1978; Read, 1962) or that which would make them vulnerable

(Weiss, 1999). Other research that supports this notion includes the social-

psychological research on the suppression of bad news in communication

(Rosen & Tesser, 1970) and research dealing with the suppression of infor-

mation that reflects adversely on the units that possess the information

(Carter, 1972).

Rewards for sharing. Real and perceived rewards and penalties for individu-

als that come from sharing and not sharing knowledge also influence the

knowledge-sharing process. O’Reilly and Pondy (1980) indicated that the

probability that organizational members will route information to other mem-

bers is positively related to the rewards and negatively related to the penalties

that they expect to result from sharing. The relationship between knowledge

sharing and incentives was further supported by studies (e.g., Gupta &

Govindarajan, 2000; Quinn et al., 1996) finding that significant changes had to

be made in the incentive system to encourage individuals to share their knowl-

edge, particularly through technology-based networks in organizations.

Rewards have also been considered important to knowledge sharing within

intranets (Hall, 2001), in the creation and sustenance of knowledge-sharing

networks (Dyer & Nobeoka, 2000), and the success of knowledge-management

initiatives within organizations (Earl, 2001; Liebowitz, 1999).

Although there are those who perceive rewards and incentives to be indis-

pensable to knowledge sharing (e.g., Gupta & Govindarajan, 2000;

O’Reilly & Pondy, 1980; Quinn et al., 1996), others have argued that tangi-

ble rewards alone are not sufficient to motivate knowledge sharing among

individuals. Professionals participate in knowledge-sharing activities

because of the intrinsic reward that comes from the work itself (Tissen,

Andriessen, & Deprez, 1998), and in some cases, formal rewards may be

perceived as demeaning by professionals who are motivated by a sense of

involvement and contribution (McDermott & O’Dell, 2001). Yet others

argued against the use of incentives to share knowledge claiming that in the

long run, unless knowledge-sharing activities help employees meet their

own goals, tangible rewards alone will not help to sustain the system

(O’Dell & Grayson, 1998).

Bartol and Srivastava (2002) proposed a relationship between different

types of knowledge sharing and monetary reward systems. They identified

four mechanisms of knowledge sharing—individual contribution to data-

bases, formal interactions within and between teams, knowledge sharing

across work units, and knowledge sharing through informal interactions.

Bartol and Srivastava suggested that monetary rewards could be instituted

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Ipe / KNOWLEDGE SHARING 349

to encourage knowledge sharing through the first three mechanisms,

whereas informal knowledge sharing would be rewarded by intangible

incentives such as enhancing the expertise and recognition of individuals.

Opportunities to Share

Opportunities to share knowledge in organizations can be both formal

and informal in nature. Formal opportunities include training programs,

structured work teams, and technology-based systems that facilitate the

sharing of knowledge. Bartol and Srivastava (2002) referred to these as

“formal interactions,” and Rulke and Zaheer (2000) called them “purposive

learning channels”—those that are designed to explicitly acquire and dis-

seminate knowledge. Informal opportunities include personal relationships

and social networks that facilitate learning and the sharing of knowledge

(Brown & Duguid, 1991; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). Rulke and Zaheer

referred to these informal opportunities as “relational learning channels.”

Purposive learning channels provide individuals with a structured envi-

ronment in which to share knowledge. Okhuysen and Eisenhardt (2002)

identified some formal interventions that facilitate knowledge sharing in

organizations, from basic instructions to share knowledge, to more complex

interventions such as Nominal Group Technique and the Delphi Technique.

Formal interventions and opportunities not only create a context in which to

share knowledge but also provide individuals with the tools necessary to do

so. However, knowledge shared through formal channels tends to be mainly

explicit in nature (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Rulke & Zaheer, 2000). The

advantages of purposive learning channels are that they are able to connect

a large number of individuals and they allow for the speedy dissemination

of shared knowledge, especially through electronic networks and other

technology-based systems. Empirical evidence for successful knowledge

sharing through formal channels was found by Constant, Sproull, and

Kiesler (1996) and Hickins (1999).

Although purposive learning channels play an important role in facilitat-

ing knowledge sharing, research indicates that the most amount of knowl-

edge is shared in informal settings—through the relational learning chan-

nels (e.g., Jones & Jordan, 1998; Pan & Scarbrough, 1999; Truran, 1998).

Relational channels facilitate face-to-face communication, which allows

for the building of trust, which in turn is critical to sharing knowledge.

These informal opportunities to interact with other people help individuals

develop respect and friendship, which influences their behavior (Nahapiet

& Ghoshal, 1998). Granovetter (1992) called this “relational embedded-

ness”—the kind of personal relationships that people develop when they

interact with each other over a period of time. Brown and Duguid (1991), in

their analysis of communities of practice found that shared learning is

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

350 Human Resource Development Review / December 2003

located in complex, collaborative practices involving informal networks

within the community. Stevenson and Gilly (1991) found that even when

clearly designated channels of communication existed in organizations,

individuals tend to rely more on informal relationships for communication.

Culture of the Work Environment

The factors described above are important to understanding the manner

in which knowledge is shared between individuals. However, all of these

factors are influenced by the culture of the work environment—the culture

of the subunit and/or the culture of the organization at large. Organizational

culture is increasingly being recognized as a major barrier to effective

knowledge creation, sharing, and use (De Long & Fahey, 2000; Leonard-

Barton, 1995; Pan & Scarbrough, 1999). Organizations are essentially cul-

tural entities (Cook & Yanow, 1993), and therefore, regardless of what orga-

nizations do to manage knowledge, the influences of the organization’s cul-

ture are much stronger (McDermott & O’Dell, 2001).

Schein (1985) defined culture as a “pattern of basic assumptions” (p. 9)

that is developed by a group as they grapple with and develop solutions to

everyday problems. When these assumptions work well enough to be con-

sidered valid, they are taught to new members as the appropriate way to

approach these problems. Schein further added that a key part of every cul-

ture is a set of assumptions about how to determine or discover what is real

and “how members of a group take an action, how they determine what is rel-

evant information, and when they have enough of it, to determine whether to

act and what to do” (p. 89). Culture is therefore reflected in the values,

norms, and practices of the organization, where values are manifested in

norms that in turn shape specific practices (De Long & Fahey, 2000).

De Long and Fahey (2000) identified certain aspects of organizational

culture that influence knowledge sharing—culture shapes assumptions

about which knowledge is important, it controls the relationships between

the different levels of knowledge (organizational, group, and individual),

and it creates the context for social interaction. It is also culture that deter-

mines the norms regarding the distribution of knowledge between an orga-

nization and the individuals in it (Staples & Jarvenpaa, 2001). Norms and

practices that advocate individual ownership of knowledge severely impede

the process of knowledge sharing within the organization, as the “organiza-

tional culture orients the mindset and action of every employee” (Nonaka &

Takeuchi, 1995, p. 167). Culture suggests what to do and what not to do

regarding knowledge processing and communication in organizations

(Davenport, 1997). An important component of culture in organizations is

corporate vision (Gold, Malhotra, & Segars, 2001; Leonard-Barton, 1995).

Gold et al. (2001) pointed to the fact that a corporate vision not only pro-

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Ipe / KNOWLEDGE SHARING 351

vides a sense of purpose to the organization but also helps to create a system

of organizational values. Organizational values that influence knowledge

sharing include the creation of a sense of involvement and contribution

among employees (O’Dell & Grayson, 1998), the types of knowledge that

are valued (Leonard-Barton, 1995), and knowledge-related values such as

trust and openness (Eisenberg & Riley, 2001; von Krogh, 1998).

An organization’s culture also shapes the perceptions and behaviors of its

employees (De Long & Fahey, 2000), and one way it does this is by estab-

lishing the context for social interactions within the organization (Gold

et al., 2001; Trice & Beyer, 1993). According to De Long and Fahey (2000),

the impact of culture on the context for social interaction can be assessed

along three dimensions—vertical interactions (interactions with senior

management), horizontal interactions (interactions with individuals at the

same level in the organization), and special behaviors that promote knowl-

edge sharing and use (sharing, teaching, and dealing with mistakes).

Cultures are not homogenous across an organization (McDermott &

O’Dell, 2001). Within organizations, there are also subcultures that are

characterized by a distinct set of values, norms and practices, often resulting

in their members valuing knowledge differently from other groups within

the same organization (Pentland, 1995). Subcultures and their influence on

knowledge sharing add even more complexity to determining those prac-

tices and norms that create the right environment to facilitate the sharing of

knowledge.

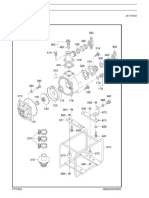

Figure 1 represents the factors identified from the literature that influ-

ence the process of knowledge sharing between individuals in organiza-

tions.

Relationship Between the Factors

That Influence Knowledge Sharing

The four factors that have been identified are significant by themselves

but do not exert their influence on knowledge sharing in isolation. The

nature of knowledge, the motivation to share, the opportunities to share, and

the culture of the work environment are all interconnected, with each factor

influencing the other in a nonlinear fashion. Figure 2 represents a model of

knowledge sharing between individuals in organizations that emerged from

the review of literature. The model presents the four factors and illustrates

the relationship between them.

The model indicates that the first three factors—nature of knowledge,

motivation to share, and opportunities to share—are embedded within the

culture of the work environment, be it the culture of the organization or the

subculture within the specific work area. Culture has an influence on the

other three factors in that the culture of the organization dictates to a fairly

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

352 Human Resource Development Review / December 2003

Tacit & explicit knowledge

Internal factors

Value of knowledge

Power

Reciprocity

External factors

Relationship with recipient

Rewards for sharing Nature of

Knowledge Purposive learning channels

Relational learning channels

Knowledge

Sharing

Motivation Opportunities

to Share to Share

Culture of work environment

FIGURE 1: Factors That Influence Knowledge Sharing Between Individuals in

Organizations

Individual

Culture

Nature of

Knowledge

Knowledge

Sharing

Motivation

to Share Opportunities to

Share

Culture Culture

Individual Individual

FIGURE 2: A Model of Knowledge Sharing Between Individuals in Organizations

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Ipe / KNOWLEDGE SHARING 353

large extent how and what knowledge is valued, what kinds of relationships

and rewards it encourages in relation to knowledge sharing, and the formal

and informal opportunities that individuals have to share knowledge.

The following is one illustration of the interdependence between the fac-

tors indicated in the model. Individuals may not be inclined to share knowl-

edge easily if the value attributed to such knowledge is very high. However,

if there are sufficient incentives (both internal and external), then individu-

als may be motivated to share that knowledge. On the other hand, if there is

motivation to share knowledge but the opportunities to share are insufficient

or if the culture of the organization attributes power to those who are per-

ceived to possess certain knowledge, then the motivation by itself may not

result in real knowledge sharing.

All the factors identified in this model do not exert the same amount of

influence on knowledge sharing in all organizational settings. The relative

importance of each of these factors is influenced by the business objectives

of the organization, its structure, business practices and policies, reward

systems, and culture. The absence of one or more of these factors in an orga-

nization does not preclude all knowledge sharing. A certain amount of

knowledge is shared between individuals all the time, under any circum-

stance in organizations. However, the model of knowledge sharing pre-

sented here proposes that the four factors are strongly interrelated with each

other and if each of these factors is favorable to knowledge sharing, together

they create the ideal environment for knowledge sharing between individu-

als within the organization.

Implications for Research

With the increasing importance of the people perspective of knowledge in

organizations, there exist many opportunities for researchers in the area of

human resource development to advance the understanding of knowledge and

knowledge sharing. The survey of literature that led to the creation of the model

of knowledge sharing presented in this article suggests opportunities for

research that fall into the following two broad categories:

• research related to the nature of knowledge in organizations and

• research related to the knowledge-sharing process and factors that influence this

process.

According to Bhatt (1998), the study of knowledge in organizations is still a

relatively new area for research and lacks a coherent theoretical foundation. The

difficulty in finding meaningful definitions and classifications of knowledge

that apply in all settings presents a significant challenge to researchers in this

area. The following proposition captures a dilemma that tests both researchers

and practitioners alike:

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

354 Human Resource Development Review / December 2003

Proposition 1: The nature of knowledge in organizations is complex and varies

across different levels and functions in the organization. For an organization to be

successful in managing its knowledge, there needs to be a common understanding

of what constitutes knowledge across the organization.

The fact that there is as yet no shared understanding of what constitutes

knowledge in the context of organizations raises some questions for future

research in this area. How should researchers define knowledge for empirical

studies? Are the distinctions between knowledge and information worthy of

research attention?

The second category of research opportunities focuses on advancing the

understanding of knowledge-sharing processes within organizations. The fol-

lowing propositions are derived from the model presented in this article:

Proposition 2: The four factors critical to knowledge sharing between individuals

in organizations are the nature of knowledge, the motivation to share, opportuni-

ties for sharing, and the culture of the work environment.

Proposition 3: All four factors are interrelated and if each of them is favorable,

together they create an optimal environment for knowledge sharing within an

organization.

Future research could also contribute to clarifying what we know about each

of the factors that are identified in the model as influencing knowledge sharing.

Proposition 4: Knowledge is perceived and valued differently by individuals at

different levels and across different functions in organizations. The differences in

the way knowledge is identified and valued have an impact on the way knowledge

is shared among individuals.

Proposition 5: Motivation to share knowledge is determined by a combination of

internal and external factors. An ideal combination of these factors results in high

motivation among individuals to share what they know with others.

Proposition 6: Opportunities to share knowledge within organizations can be both

relational and formal in nature. A balanced combination of relational and formal

learning channels is critical to effective knowledge sharing.

Proposition 7: Culture of the work environment is the most critical factor that

influences knowledge sharing within organizations. The culture of the organiza-

tion and subcultures within the organization have a significant influence on the

other three factors.

With the rapid advances being made in the field of practice related to

knowledge management, there is a significant gap between research and prac-

tice in this area (Grover & Davenport, 2001). The increasing sophistication in

technology-based knowledge management systems call attention to one area

where more research is needed. Existing literature suggests that individuals are

more likely to share knowledge with others through informal interactions than

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Ipe / KNOWLEDGE SHARING 355

through the use of formal systems. Scholars with a human resource orienta-

tion need to partner with technologists to identify how formal and informal

knowledge-sharing processes may be combined to effectively facilitate knowl-

edge sharing in organizations. Research could also recommend how formal

means of knowledge sharing such as training programs can be redesigned to

both share knowledge effectively as well as help individuals develop “ways of

knowing that make use of knowledge in new, innovative, and more productive

ways” (Cook & Brown, 1999, p. 398).

In-depth investigative methods such as case studies and ethnographies

could be used to discover the nuances of the knowledge-sharing process

within specific organizational settings. Such studies would also be able to

identify factors that motivate and inhibit knowledge-sharing behavior

within the contexts chosen for the study. Subsequent research could then be

done to verify whether these factors apply across organizations, using meth-

ods that allow results to be generalized to larger populations. New research

in this area may also be able to identify emerging factors that influence the

knowledge-sharing process that have not been documented in the literature

thus far.

Conclusion

It is clear that knowledge sharing in organizations is a complex process

that is value laden and driven by power equations within the organization.

Knowledge in organizations is dynamic in nature and is dependent on social

relationships between individuals for its creation, sharing, and use. More

knowledge is shared informally than through formal channels, and much of

the process is dependent on the culture of the work environment. This article

has presented a model that describes knowledge sharing between individu-

als, identifying factors that have a significant influence on the knowledge-

sharing process and illustrating the relationship between these factors.

References

Allen, T. J., & Cohen, S. I. (1969). Information flow in research and development laboratories.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 14(1), 12-19.

Alvesson, M. (1993). Management of knowledge-intensive companies. New York: Walter de Gruyer.

Alvesson, M. (1995). Organizations as rhetoric: Knowledge-intensive firms and the struggle with

ambiguity. Journal of Management Studies, 30(6), 997-1015.

Alvesson, M., & Karreman, D. (2001). Odd couple: Making sense of the curious concept of knowl-

edge management. Journal of Management Studies, 38(7), 995-1018.

Andrews, K. M., & Delahaye, B. L. (2000). Influences on knowledge processes in organizational

learning: The psychological filter. Journal of Management Studies, 37(6), 2322-2380.

Armbrecht, F. M. R., Jr., Chapas, R. B., Chappelow, C. C., & Farris, G. F. (2001). Knowledge man-

agement in research and development. Research Technology Management, 44(2), 28-48.

Argyris, C. (1990). Integrating the individual and the organization. London: Transaction Publishing.

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

356 Human Resource Development Review / December 2003

Barnlund, D. C., & Harland, C. (1963). Propinquity and prestige as determinants of communication

networks. Sociometry, 26, 466-479.

Bartol, K. M., & Srivastava, A. (2002). Encouraging knowledge sharing: The role of organizational

reward systems. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 9(1), 64-77.

Becerra-Fernandez, I., & Sabherwal, R. (2001). Organizational knowledge management: A contin-

gency perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 23-55.

Bhatt, G. D. (1998). Managing knowledge through people. Knowledge and Process Management,

5(3), 165-171.

Blackler, F. (1995). Knowledge, knowledge work and organizations: An overview and interpreta-

tion. Organization Studies, 16(6), 1021-1046.

Blackler, F., Crump, N., & McDonald, S. (1998). Knowledge, organizations and competition. In

G. von Krogh, J. Roos, & D. Kleine (Eds.), Knowing in firms: Understanding, managing and

measuring knowledge (pp. 67-86). London: Sage.

Boland, R. J. J., & Tenkasi, R. V. (1995). Perspective making and perspective taking in communities

of knowing. Organization Science, 6(4), 350-372.

Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (1991). Organizational learning and communities-of-practice: Toward a

unified view of working, learning, and innovation. Organization Science, 2(1), 40-57.

Brown, R. B., & Woodland, M. J. (1999). Managing knowledge wisely: A case study in organiza-

tional behavior. Journal of Applied Management Studies, 6(2), 175-198.

Carter, R. M. (1972). Communications in organizations: A guide to information sources. Detroit:

Gale Research.

Chakravarthy, B., Zaheer, A., & Zaheer, S. (1999). Knowledge sharing in organizations: A field

study. St. Paul: University of Minnesota, Strategic Management Resource Center.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and

innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 128-152.

Constant, D., Sproull, L., & Kiesler, S. (1996). The kindness of strangers: The usefulness of elec-

tronic weak ties for technical advice. Organization Science, 7(2), 119-135.

Cook, S. D. N., & Brown, J. S. (1999). Bridging epistemologies: The generative dance between orga-

nizational knowledge and organizational knowing. Organization Studies, 10(4), 381-400.

Cook, S. D. N., & Yanow, D. (1993). Culture and organizational learning. Journal of Management

Inquiry, 2(4), 373-390.

Davenport, T. H. (1997). Information ecology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Davenport, T. H., De Long, D. W., & Beers, M. C. (1998). Successful knowledge management proj-

ects. Sloan Management Review, 39(2), 43-57.

Davenport, T. H., Eccles, R. G., & Prusak, L. (1992, Fall). Information politics. Sloan Management

Review, pp. 53-65.

Davenport, T. H., & Prusak, L. (1998). Working knowledge: How organizations manage what they

know. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

De Long, D. W., & Fahey, L. (2000). Diagnosing cultural barriers to knowledge management. The

Academy of Management Executive, 14(4), 113-127.

Dodgson, M. (1993). Organizational learning: A review of some literatures. Organization Studies,

14(3), 375-394.

Drucker, P. (1993). Post-capitalist society. New York: Harper Business.

Dyer, J. H., & Nobeoka, K. (2000). Creating and managing a high-performance knowledge-sharing

network: The Toyota case. Strategic Management Journal, 21(3), 345-367.

Earl, M. (2001). Knowledge management strategies: Towards a taxonomy. Journal of Management

Information Systems, 18, 215-233.

Eisenberg, E. M., & Riley, P. (2001). Organizational culture. In F. M. Jablin & L. L. Putnam (Eds.),

The new handbook of organizational communication (pp. 291-322). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Empson, L. (2001). Fear of exploitation and fear of contamination: Impediments to knowledge trans-

fer in mergers between professional service firms. Human Relations, 54(7), 839-862.

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Ipe / KNOWLEDGE SHARING 357

Ghoshal, S., & Bartlett, C. A. (1994). Linking organizational context and managerial action: The

dimension of quality management. Strategic Management Journal, 15 (Special Issue), 91-112.

Gold, A. H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A. H. (2001). Knowledge management: An organizational per-

spective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185-214.

Gourlay, S. (2001). Knowledge management and HRD. Human Resource Development Inter-

national, 4(1), 27-46.

Granovetter, M. S. (1992). Problems of explanation in economic sociology. In N. Nohria & R. Eccles

(Eds.), Networks and organizations: Structure, form and action (pp. 25-56). Boston: Harvard

Business School Press.

Grover, V., & Davenport, T. H. (2001). General perspectives on knowledge management: Fostering a

research agenda. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 5-21.

Gupta, A. K., & Govindarajan, V. (2000). Knowledge management’s social dimension: Lessons

from Nucor Steel. Sloan Management Review, 42(1), 71-80.

Hall, H. (2001). Input-friendliness: Motivating knowledge sharing across intranets. Journal of Infor-

mation Science, 27(3), 139-146.

Hendriks, P. (1999). Why share knowledge? The influence of ICT on the motivation for knowledge

sharing. Knowledge and Process Management, 6(2), 91-100.

Hickins, M. (1999). Xerox shares its knowledge. Management Review, 88(8), 40-45.

Huber, G. (1982). Organizational information systems: Determinants of their performance and

behavior. Management Science, 28(2), 138-155.

Huber, G. (1991). Organizational learning: The contributing processes and the literatures. Organiza-

tion Science, 2(1), 88-115.

Huemer, L., von Krogh, G., & Roos, J. (1998). Knowledge and the concept of trust. In G. von Krogh,

J. Roos, & D. Kleine (Eds.), Knowing in firms: Understanding, managing and measuring knowl-

edge (pp.123-145). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Jones, P., & Jordan, J. (1998). Knowledge orientations and team effectiveness. International Journal

of Technology Management, 16, 152-161.

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication

of technology. Organization Science, 3(3), 383-397.

Kramer, R. M. (1999). Social uncertainty and collective paranoia in knowledge communities: Think-

ing and acting in the shadow of doubt. In L. L. Thompson, J. M. Levine, & D. M. Messick (Eds.),

Shared cognition in organizations: The management of knowledge (pp. 163-194). Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum.

Krone, K. J., Jablin, F. M., & Putnam, L. L. (1987). Communication theory and organizational com-

munication: Multiple perspectives. In F. M. Jablin, L. L. Putnam, K. H. Roberts, & L. W. Porter

(Eds.), Handbook of organizational communication: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 18-

40). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Lam, A. (1997). Embedded firms, embedded knowledge: Problem of collaboration and knowledge

transfer in global cooperative ventures. Organization Studies, 18(6), 973-996.

Lam, A. (2000). Tacit knowledge, organizational learning and societal institutions: An integrated

framework. Organization Studies, 21(3), 487-513.

Leonard-Barton, D. (1995). Wellsprings of knowledge: Building and sustaining the source of innova-

tion. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Lessard, D. R., & Zaheer, S. (1996). Breaking the silos: Distributed knowledge and strategic

responses to volatile exchange rates. Strategic Management Journal, 17(7), 513-543.

Liebowitz, J. (1999). Key ingredients to the success of an organization’s knowledge management

strategy. Knowledge and Process Management, 6(1), 37-40.

Lowendahl, B. R., Revang, O., & Fosstenlokken, S. M. (2001). Knowledge and value creation in pro-

fessional service firms: A framework for analysis. Human Relations, 54(7), 911-931.

McDermott, R. (1999). Why information technology inspired but cannot deliver: Knowledge man-

agement. California Management Review, 41(4), 103-117.

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

358 Human Resource Development Review / December 2003

McDermott, R., & O’Dell, C. (2001). Overcoming cultural barriers to sharing knowledge. Journal of

Knowledge Management, 5(1), 76-85.

Molm, L. D., Takahashi, N., & Peterson, G. (2000). Risk and trust in social exchange: An experimen-

tal test of a classical proposition. American Journal of Sociology, 105, 1396-1426.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital and the organizational advan-

tage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242-266.

Nidumolu, S. R., Subramani, M., & Aldrich, A. (2001). Situated learning and the situated knowledge

web: Exploring the ground beneath knowledge management. Journal of Management Informa-

tion Systems, 18(1), 115-150.

Nonaka, I. (1994). The dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science,

5(1), 14-37.

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge creating company: How Japanese companies cre-

ate the dynamics of innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

O’Dell, C., & Grayson, C. J. J. (1998). If only we knew what we know. New York: Free Press.

Okhuysen, G. A., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2002). Integrating knowledge in groups: How formal inter-

ventions enable flexibility. Organization Science, 13(4), 370-386.

O’Reilly, C. (1978). The intentional distortion of information in organizational communication: A

laboratory and field investigation. Human Relations, 31, 173-193.

O’Reilly, C., & Pondy, L. (1980). Organizational communication. In S. Kerr (Ed.), Organizational

behavior. Columbus, OH: Grid.

Orr, J. E. (1990). Sharing knowledge, celebrating identity: Community memory in a service culture.

In D. S. Middleton & D. Edwards (Eds.), Collective remembering: Memory in society (pp. 169-

189). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Pan, S. L., & Scarbrough, H. (1999). Knowledge management in practice: An exploratory case study.

Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 11(3), 359-374.

Pemberton, M. J. (1998). Knowledge management (KM) and the epistemic tradition. Records Man-

agement Quarterly, 32(3), 58-62.

Pentland, B. T. (1995). Information systems and organizational learning: The social epistemology

of organizational knowledge systems. Accounting, Management and Information Technology,

5(1), 1-21.

Pfeffer, J. (1980). Power in organizations. Marshfield, MA: Pitman.

Polanyi, M. (1966). The tacit dimension. London: Routledge Kegan Paul.

Quinn, J. B., Anderson, P., & Finkelstein, S. (1996). Leveraging intellect. Academy of Management

Executive, 10, 7-27.

Read, W. M. (1962). Upward communication in industrial hierarchies. Human Relations, 15, 3-15.

Roberts, J. (2000). From know-how to show-how? Questioning the role of information and commu-

nication technologies in knowledge transfer. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management,

12(4), 429-443.

Roos, J., & von Krogh, G. (1992). Figuring out your competence configuration. European Manage-

ment Journal, 10(4), 422-444.

Rosen, S., & Tesser, A. (1970). On reluctance to communicate undesirable information: The MUM

effect. Sociometry, 33(3), 253-263.

Rulke, D. L., & Zaheer, S. (2000). Shared and unshared transactive knowledge in complex organiza-

tions: An exploratory study. In Z. Shapira & T. Lant (Eds.), Organizational cognition: Computa-

tion and interpretation. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Schein, E. H. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schultz, M. (2001). The uncertain relevance of newness: Organizational learning and knowledge

flows. Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 661-681.

Simon, H. A. (1991). Bounded rationality and organizational learning. Organization Science, 2, 125-

134.

Spender, J. C., & Grant, R. M. (1996). Knowledge and the firm: Overview. Strategic Management

Journal, 17, 5-9.

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Ipe / KNOWLEDGE SHARING 359

Staples, S. D., & Jarvenpaa, S. L. (2001). Exploring perceptions of organizational ownership of

information and expertise. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 151-183.

Stenmark, D. (2001). Leveraging tacit organizational knowledge. Journal of Management Informa-

tion Systems, 17(3), 9-24.

Stevenson, W. B., & Gilly, M. C. (1991). Information processing and problem solving: The migra-

tion of problems through formal positions and networks of ties. Academy of Management Jour-

nal, 34(4), 918-928.

Stewart, T. A. (1997). Intellectual capital: The new wealth of organizations. New York: Doubleday

Currency.

Tissen, R., Andriesson, D., & Deprez, L. F. (1998). Value-based knowledge management: Creating

st

the 21 century company: Knowledge intensive, people rich. Amsterdam: Addison-Wesley

Longman.

Trice, H. M., & Beyer, J. M. (1993). The cultures of work organizations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice Hall.

Truran, W. R. (1998). Pathways for knowledge: How companies learn through people. Engineering

Management Journal, 10(4), 15-20.

Tsoukas, H., & Vladimirou, E. (2001). What is organizational knowledge? Journal of Management

Studies, 38(7), 973-993.

von Hippel, E. (1994). “Sticky information” and the locus of problem solving: Implications for inno-

vation. Management Science, 40, 429-430.

von Krogh, G. (1998). Care in knowledge creation. California Management Review, 40(3), 133-153.

Venzin, M., von Krogh, G., & Roos, J. (1998). Future research into knowledge management. In G. R.

von Krogh, R. Johan, & D. Kleine (Eds.), Knowing in firms: Understanding, managing and mea-

suring Knowledge (pp. 26-66). London: Sage.

Weiss, L. (1999). Collection and connection: The anatomy of knowledge sharing in professional ser-

vice. Organization Development Journal, 17(4), 61-72.

Zand, D. (1972). Trust and managerial problem solving. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17, 229-

239.

Minu Ipe recently completed a Ph.D. specializing in human resource develop-

ment from the University of Minnesota. She has been involved with both the

technology and people aspects of knowledge management for several years,

first as an HRD manager and then as a student and researcher. Her interests

include knowledge mapping, knowledge processes within and across teams,

cross-cultural issues related to knowledge management, and organizational

learning.

Downloaded from http://hrd.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2003 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- 1.knowledge Sharing in Organizations A Conceptual FrameworkDocument24 pagini1.knowledge Sharing in Organizations A Conceptual FrameworkMusadaq Hanandi100% (1)

- Nonaka DynamicTheoryOrganizational 1994Document25 paginiNonaka DynamicTheoryOrganizational 1994Milin Rakesh PrasadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review Knowledge Management and Knowledge ManagemeDocument31 paginiReview Knowledge Management and Knowledge Managemeaishah farahÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Literature Review On Knowledge Sharing: Tingting ZhengDocument8 paginiA Literature Review On Knowledge Sharing: Tingting ZhengEra ChaudharyÎncă nu există evaluări