Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Bring Back Home Economics Education

Încărcat de

agcDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Bring Back Home Economics Education

Încărcat de

agcDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

COMMENTARY

Bring Back Home Economics Education

Alice H. Lichtenstein, DSc hunger paradox” arises not only from lack of nutritious, af-

fordable alternatives to fast food, but also from lack of knowl-

David S. Ludwig, MD, PhD edge about how to prepare nutritious food at home with

inexpensive basic ingredients. At the other extreme, high-

H

OME ECONOMICS, OTHERWISE KNOWN AS DOMES- end kitchen appliances now feature “smart” options for cook-

tic education, was a fixture in secondary schools ies, chicken nuggets, and omelets, allowing those with mini-

through the 1960s, at least for girls. The under- mal cooking skills to prepare dishes or entire meals with

lying concept was that future homemakers should the push of a button.5

be educated in the care and feeding of their families. This Although the optimal diet for obesity and chronic dis-

idea now seems quaint, but in the midst of a pediatric obe- ease prevention remains the subject of investigation, broad

sity epidemic and concerns about the poor diet quality of consensus exists regarding the benefits of home-prepared

adolescents in the United States, instruction in basic food meals. Research suggests that frequent consumption of res-

preparation and meal planning skills needs to be part of any taurant food, take-out food, and prepared snacks lowers di-

long-term solution. etary quality and promotes weight gain,6,7 and that food

About 35% of adolescents are overweight or obese, a preva- preparation by adolescents and young adults may have the

lence that approaches 50% in minority populations.1 Ex- opposite effect by displacing poor choices made outside the

cessive weight among youth affects virtually every organ sys- home.8 The increase in consumption of meals and snacks

tem and, according to a recent study, increases the risk of prepared away from home, now exceeding one-third of total

premature death.2 In addition, obesity adversely affects self- calories among children and adolescents,9 appears related

esteem, academic accomplishment, and future earning po- to the obesity epidemic.

tential of children.3 Even more than before, parents and caregivers today can-

Programs meant to address obesity in youth have achieved not be expected or relied on to teach children how to pre-

limited success. Some localities have begun to screen stu- pare healthy meals. Many parents never learned to cook and

dents with body mass index (BMI) “report cards,” formed instead rely on restaurants, take-out food, frozen meals, and

innovative relationships with farmers to supplement the packaged food as basic fare. Many children seldom experi-

school lunch with local produce, and enacted moratori- ence what a true home-cooked meal tastes like, much less

ums on locating new fast food establishments in their neigh- see what goes into preparing it. Work schedules and child

borhoods. But powerful forces undermine these efforts, such extracurricular programs frequently preclude involving chil-

as the ubiquitous advertising of foods and beverages high dren in food shopping and preparation. The family dinner

in calories and low in nutrient content. has become the exception rather than the rule.

Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move” campaign—with its To improve education about food, it is not necessary to

emphasis on improving the quality of food and beverage in bring back the classic home economics coursework,

the schools and the community—is a welcome and his- replete with gender-specific stereotypes. Rather, girls and

toric step. However, better choices in schools will ulti- boys should be taught the basic principles they will need

mately have limited effects if children do not have the abil- to feed themselves and their families within the current

ity to make better choices in the outside-school world, food environment: a version of hunting and gathering for

where they spend the majority of their time when young the 21st century. Through a combination of pragmatic

and which they inhabit when older. If children are raised instruction, field trips, and demonstrations, this curricu-

to feel uncomfortable in the kitchen, they will be at a dis- lum would aim to transform meal preparation from an

advantage for life. intimidating chore into a manageable and rewarding pur-

Two recent reports underscore the urgency of this situ-

Author Affiliations: Cardiovascular Research Laboratory, Jean Mayer USDA

ation. One story focusing on impoverished areas of the South Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging, Tufts University, Boston, Massa-

Bronx identified a novel phenomenon in the United States: chusetts (Dr Lichtenstein); Optimal Weight for Life Program, Department of

Medicine, Children’s Hospital, Boston (Dr Ludwig).

the coexistence of food insecurity and obesity in the same Corresponding Author: Alice H. Lichtenstein, DSc, Tufts University, 711 Wash-

families and sometimes in the same individual.4 This “obesity- ington St, Boston, MA 02111 (alice.lichtenstein@tufts.edu).

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, May 12, 2010—Vol 303, No. 18 1857

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a Otterbein University User on 06/03/2015

COMMENTARY

suit. As children transition into young adulthood, they vated home economics curriculum could equip young adults

should be provided with knowledge to harness modern with the skills essential to lead long healthy lives and re-

conveniences (eg, prewashed salad greens) and avoid pit- verse the trends of obesity and diet-related diseases. This

falls in the marketplace (eg, prepared foods with a high instruction will also help youth reestablish a healthy rela-

ratio of calories to nutrients) to prepare meals that are tionship with food, protecting them from the constant on-

quick, nutritious, and tasty. It is important to dispel the slaught of weight-loss diets and body-building fads.

myths—aggressively promoted by some in the food Obesity presently costs society almost $150 billion an-

industry—that cooking takes too much time or skill and nually in increased health care expenditures.10 The per-

that nutritious food cannot also be delicious. sonal and economic toll of this epidemic will only increase

A comprehensive curriculum to teach students about as this generation of adolescents develops weight-related

the scientific and practical aspects of food might include complications such as type 2 diabetes earlier in life than ever

basic cooking techniques; caloric requirements; sources of before. From this perspective, providing a mandatory food

food, from farm to table; budget principles; food safety; preparation curriculum to students throughout the coun-

nutrient information, where to find it and how to use it; try may be among the best investments society could make.

and effects of food on well-being and risk for chronic dis-

Financial Disclosures: Dr Lichtenstein reported receiving grants from the Na-

ease. This curriculum would provide adolescents, espe- tional Institutes of Health for cardiovascular disease–related research. Dr Ludwig

cially at the high school level, with the skills they need to reported receiving royalties from a book about childhood obesity and grants from

foundations and the National Institutes of Health for obesity-related research, men-

become confident in selecting, handling, and preparing toring, and patient care.

food. To minimize competition with other curricular Funding/Support: Dr Lichtenstein is supported in part by grants from the Na-

activities, many of these topics could be integrated into tional Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Diabetes and Diges-

tive and Kidney Diseases; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr

existing science, math, economics, physical activity, and Ludwig is supported in part by career award K24DK082730 from the National In-

social studies coursework. Some additional time during stitute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Role of Sponsors: Funding sources had no role in the preparation, review, or ap-

the school day would be required for hands-on cooking proval of the manuscript.

classes and field trips. However, with improvements in Disclaimer: The content of this commentary is solely the responsibility of the au-

thors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart,

dietary quality that may result from the new curriculum, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and

mental performance may increase, tending to compensate Kidney Diseases; or the National Institutes of Health.

Additional Contributions: Simone French, PhD, University of Minnesota, and Nancy

for any modest reductions in time available for other Fliesler, Children’s Hospital, Boston, provided thoughtful suggestions about the

classes. manuscript. Neither received compensation for their contributions.

Education in food preparation would produce meaning-

ful synergy with environmental changes in schools, espe- REFERENCES

cially improvement in food quality at breakfast and lunch.

1. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high

School cafeterias could be renovated to allow for prepara- body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007-2008. JAMA. 2010;

tion of cooked meals from raw ingredients, rather than just 303(3):242-249.

2. Franks PW, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, Sievers ML, Bennett PH, Looker HC. Child-

the reheating of frozen foods by microwave or deep frying, hood obesity, other cardiovascular risk factors, and premature death. N Engl J Med.

as has become the norm. Instead of using candy as an aid 2010;362(6):485-493.

3. Gortmaker SL, Must A, Perrin JM, Sobol AM, Dietz WH. Social and economic

to teach counting in math class, more positive messages about consequences of overweight in adolescence and young adulthood. N Engl J Med.

health and nutrition could be creatively incorporated into 1993;329(14):1008-1012.

coursework for students of all ages. 4. Dolnick S. The obesity-hunger paradox. New York Times. March 12, 2010. http:

//www.nytimes.com/2010/03/14/nyregion/14hunger.html. Accessed April 5, 2010.

An informed generation of children may also influence 5. Severson K. Kitchen gadgets take the fast-food mentality into the home. New

the eating habits of US families, just as tobacco education York Times. March 16, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/17/dining

/17house.html. Accessed April 5, 2010.

causes some students to discourage their parents from smok- 6. Taveras EM, Berkey CS, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Association of consumption of

ing. Ultimately, as this generation of school-aged children fried food away from home with body mass index and diet quality in older chil-

dren and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;116(4):e518-e524.

and adolescents reaches adulthood, they may serve as posi- 7. Thompson OM, Ballew C, Resnicow K, et al. Food purchased away from home

tive role models for their children and, through their long- as a predictor of change in BMI z-score among girls. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord.

term purchasing habits, ensure healthful food choices are 2004;28(2):282-289.

8. Larson NI, Perry CL, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Food preparation by young

readily available in homes, supermarkets, and restaurants adults is associated with better diet quality. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(12):

throughout the country. 2001-2007.

9. Nielsen SJ, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. Trends in energy intake in US between

Presently, many US schools provide information and guid- 1977 and 1996: similar shifts seen across age groups. Obes Res. 2002;10(5):

ance about tobacco, alcohol, drugs, sexually transmitted dis- 370-378.

10. Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending

ease, and pregnancy; they should do the same about one of attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Aff (Millwood).

the most fundamental of human activities: eating. A reno- 2009;28(5):w822-w831.

1858 JAMA, May 12, 2010—Vol 303, No. 18 (Reprinted) ©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a Otterbein University User on 06/03/2015

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Biochemical Changes During Ripening of Banana: A ReviewDocument5 paginiBiochemical Changes During Ripening of Banana: A ReviewagcÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Strategies in Sport NutritionDocument15 paginiNew Strategies in Sport NutritionagcÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10 11648 J Jfns 20140202 12 PDFDocument6 pagini10 11648 J Jfns 20140202 12 PDFagcÎncă nu există evaluări

- CLothing and Colonial Culture of Appearances in 19th C Philippines PHD Diss Full Coo 2014 PDFDocument619 paginiCLothing and Colonial Culture of Appearances in 19th C Philippines PHD Diss Full Coo 2014 PDFagcÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Nutritional Basis of The Fetal Origins of Adult DiseaseDocument4 paginiThe Nutritional Basis of The Fetal Origins of Adult DiseaseagcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- 207 Bushcraft and Indigenous Knowledge Transformations of A Concept in The MDocument320 pagini207 Bushcraft and Indigenous Knowledge Transformations of A Concept in The MCaroline BirkoffÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teacher As Researcher BibliographyDocument1 paginăTeacher As Researcher BibliographyThu DangÎncă nu există evaluări

- MathiDocument2 paginiMathiAndrewAseerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literary Arts ScriptDocument3 paginiLiterary Arts ScriptRidge Justine TacasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Janine Clark ResumeDocument1 paginăJanine Clark ResumeJanine ClarkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Resume OF Md. Syful Islam: Contract AddressDocument2 paginiResume OF Md. Syful Islam: Contract Addressmd Syful islamÎncă nu există evaluări

- UPM Citizens Charter 2020 2nd EditionDocument417 paginiUPM Citizens Charter 2020 2nd EditionKikiyo MoriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Action Research PosterDocument1 paginăAction Research Posterapi-384464451Încă nu există evaluări

- Mallorie Taylor: Currently EnrolledDocument2 paginiMallorie Taylor: Currently Enrolledapi-457032346Încă nu există evaluări

- CBSE Schools in PALAKKAD KeralaDocument16 paginiCBSE Schools in PALAKKAD KeralatayyabaariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11 CGP Module 3Document8 pagini11 CGP Module 3John Paul ColibaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anecdotal ComponentDocument6 paginiAnecdotal Componentapi-284976539Încă nu există evaluări

- Module 1 in Assessment and Evaluation in MathematicsDocument28 paginiModule 1 in Assessment and Evaluation in MathematicsMary May C. MantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample ResearchDocument23 paginiSample ResearchMark Vic CasanovaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module Review For Practicum in Educational AdministrationDocument62 paginiModule Review For Practicum in Educational AdministrationCorazon R. LabasanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Talking Out of TurnDocument1 paginăTalking Out of Turnapi-313689709Încă nu există evaluări

- School Bullying Among The Students in SchoolDocument2 paginiSchool Bullying Among The Students in SchoolCHAN QIAN HUI 17106Încă nu există evaluări

- Https Mlisresources - Info Booklist Class IX - IGCSEDocument2 paginiHttps Mlisresources - Info Booklist Class IX - IGCSErizwaniamina08Încă nu există evaluări

- 127 Ngaruawahia High School Confirmed Education Review ReportDocument8 pagini127 Ngaruawahia High School Confirmed Education Review ReportJoshua WoodhamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Homeroom Pta OfficialsDocument9 paginiHomeroom Pta Officialsapi-265708356Încă nu există evaluări

- Thespian MembershipDocument2 paginiThespian Membershipapi-233668773Încă nu există evaluări

- AAUW AcademicFields PDFDocument2 paginiAAUW AcademicFields PDFIovu CiprianÎncă nu există evaluări

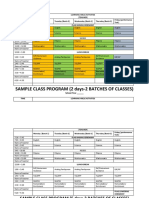

- DepEd Sample Class Program and Teachers ScheduleDocument4 paginiDepEd Sample Class Program and Teachers ScheduleAnnalyn ModeloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Congratulations Class of 2012Document8 paginiCongratulations Class of 2012MaconNewsÎncă nu există evaluări

- XLVI ESAN INTERNATIONAL WEEK (MBA Only - July 2023)Document38 paginiXLVI ESAN INTERNATIONAL WEEK (MBA Only - July 2023)Juan Diego Fernández CastilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Influence of Using Word Wall Media Toward Students' Analytical Exposition Writing at Eleventh Grade of SMK Jaya BuanaDocument162 paginiThe Influence of Using Word Wall Media Toward Students' Analytical Exposition Writing at Eleventh Grade of SMK Jaya Buanadaniel evansaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bankim - CB Rady PDFDocument2 paginiBankim - CB Rady PDFBankim BiswasÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Basat!Document2 paginiWhat Is Basat!chakokeli100% (1)

- Professors and Contact Information:: FYS 1002: First Year Seminar: Expository, Cross-Cultural WritingDocument5 paginiProfessors and Contact Information:: FYS 1002: First Year Seminar: Expository, Cross-Cultural WritingAnonymous EBfEc4agyzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 1 - FinalDocument12 paginiModule 1 - FinalChristian Joy MauricioÎncă nu există evaluări