Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Depression and Suicide Risk in Hemodialysis Patients

Încărcat de

basti_aka_slimDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Depression and Suicide Risk in Hemodialysis Patients

Încărcat de

basti_aka_slimDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Depression and Suicide Risk in Hemodialysis

Patients With Chronic Renal Failure

Chih-Ken Chen, M.D., Ph.D., Yi-Chieh Tsai, B.S., Heng-Jung Hsu, M.D.

I-Wen Wu, M.D., Chiao-Yin Sun, M.D., Chia-Chi Chou, M.D.

Chin-Chan Lee, M.D., Chi-Ren Tsai, M.D.

Mai-Szu Wu, M.D., Liang-Jen Wang, M.D.

Background: Depression and suicide are well established as prevalent mental health problems for pa-

tients on hemodialysis. Objective: The authors examined the demographic and psychological factors asso-

ciated with depression among hemodialysis patients and elucidated the relationships between depression,

anxiety, fatigue, poor health-related quality of life, and increased suicide risk. Method: This cross-sec-

tional study enrolled 200 end-stage renal disease patients age ⱖ18 years on hemodialysis. Psychological

characteristics were assessed with the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, the Hospital Anxiety

and Depression Scale, the short-form Health-Related Quality of Life Scale, and Chalder Fatigue Scale,

and structural equation modeling was used to analyze the models and the strength of relationships between

variables and suicidal ideation. Results: Of the 200 patients, 70 (35.0%) had depression symptoms, and 43

(21.5%) had had suicidal ideation in the previous month. Depression was significantly correlated with a

low body mass index (BMI) and the number of comorbid physical illnesses. Depressed patients had greater

levels of fatigue and anxiety, more common suicidal ideation, and poorer quality of life than nondepressed

patients. Results revealed a significant direct effect for depression and anxiety on suicidal ideation. Con-

clusion: Among hemodialysis patients, depression was associated with a low BMI and an increased num-

ber of comorbid physical illnesses. Depression and anxiety were robust indicators of suicidal ideation. A

prospective study would prove helpful in determining whether early detection and early intervention of

comorbid depression and anxiety among hemodialysis patients would reduce suicide risk.

(Psychosomatics 2010; 51:528 –528.e6)

H emodialysis significantly and adversely affects the

lives of patients, both physically and psychologi-

cally.1–3 The global influence on family roles, work

ease is one of the top 10 causes of death in Taiwan. An

international comparison determined that Taiwan had

the greatest incidence and second-greatest prevalence of

competence, fear of death, and dependency on treatment end-stage renal disease (ESRD).4 Postulated explana-

may negatively affect quality of life and exacerbate tions for high incidence and prevalence of ESRD in

feelings associated with a loss of control.2,3 Renal dis- Taiwan include high prevalence and incidence of

chronic kidney disease, failure to identify patients with

an early stage of chronic kidney disease, and an in-

Received June 17, 2010; revised July 15, 2010; accepted July 16, 2010.

From the Dept. of Psychiatry and Nephrology, Chang Gung Memorial creased elderly population.4 Roughly 95% of ESRD

Hospital at Keelung, Taiwan; Chang Gung University School of Medi- patients in Taiwan are on hemodialysis.5 Therefore, it is

cine, Taiwan; Division of Mental Health and Drug Abuse Research,

National Health Research Institute, Miaoli, Taiwan; and the Master of important to determine the psychological effects of he-

Public Health Degree Program, College of Public Health, National Tai- modialysis.

wan University, Taipei, Taiwan. Send correspondence and reprint re-

quests to Liang-Jen Wang, M.D., Dept. of Psychiatry, Chang Gung Depression is the most common psychological prob-

Memorial Hospital at Keelung. No. 200 Ave 208 Chi-Chin-Yi Rd.,

Keelung, Taiwan. e-mail: WangLiangJen@gmail.com

lem among hemodialysis patients. In the general popula-

© 2010 The Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine tion, the prevalence of major depression is approximately

528 http://psy.psychiatryonline.org Psychosomatics 51:6, November-December 2010

Chen et al.

1.1%–15% for men and 1.8%–23% for women.6 However, was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang

the prevalence of major depression among ESRD patients Gung Memorial Hospital.

is approximately 20%–30%,3 and it may be as high as

47%.7 Furthermore, a strong correlation exists between Procedures

depression and mortality for long-term hemodialysis pa-

tients.1,8,9 The incidence of anxiety, also a disorder com- In this cross-sectional study, all hemodialysis patients

mon to hemodialysis patients, is 27%– 46%.10,11 The co- underwent assessments for fatigue symptoms with the

morbidities of depression and anxiety increased over time Chalder Fatigue Scale (CFS), for depressive symptoms

in subjects who were on hemodialysis in a 16-month fol- with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),

low-up study.11 and the Short-Form Health-Related Quality of Life Scale

Fatigue is a subjective symptom characterized by (SF–36), as well as psychiatric diagnostic interviews, us-

tiredness, weakness, and lack of energy.12 Roughly 60%– ing the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview

97% of patients on hemodialysis experience some fa- (MINI).

tigue.13 Fatigue is also one of the most debilitating symp-

toms reported by hemodialysis patients, and it is Measures

negatively correlated with quality of life.14 Health-related

quality of life is an important measure of how a disease Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) Psy-

affects the lives of patients. The quality of life domains chiatric diagnoses were made by the criteria in the 4th

include physical, psychological, and social functioning Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

and general satisfaction with life.15 Numerous studies Disorders (DSM–IV) after a structured psychiatric inter-

have demonstrated that hemodialysis patients had a lower view using the MINI. The MINI is a short, structured

quality of life than that of a healthy population.16 –18 diagnostic interview for psychiatric disorders.23 This

Suicide may be the gravest result of depression. Cor- structured interview has good reliability and has been

roborative evidence has identified a high incidence of sui- widely used in international clinical trials and epidemio-

cide threats and attempts among hemodialysis patients; logical studies.24 The interrater reliability of the Mandarin

however, suicide risk differed among studies.19,20 Suicidal MINI, which was translated by the Taiwan Society of

ideation and attempt are associated with depression and Psychiatry, is roughly 0.75.25

anxiety in the general population.21 A high suicide rate is Suicide risk was also assessed with the Suicide mod-

also related to poor quality of life.22 Identification of the ule of the MINI.23 This module uses specific questions to

relationships between psychological issues and suicide assess suicidal ideation, suicide plans, and suicide at-

risk for dialysis patients is crucial. tempts within the past month and lifetime suicide attempts.

Currently, the relationships between suicide, de-

pression, anxiety, fatigue, and life quality remain The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) The

poorly understood. The objective of this study is to HADS is a 14-item, self-administered questionnaire for

identify the demographic and psychological factors as- assessing the severity of depression.26 The HADS is com-

sociated with depression in hemodialysis patients. This monly used in hospital practice and primary care, and for

study also elucidates the relationships among depres- the general population. Seven items assess anxiety, and the

sion, anxiety, fatigue, health-related quality of life, and other seven items assess depression. Each item has four

suicide risk. possible responses (scored 0 –3); the Anxiety and Depres-

sion subscales are independent measures. Patients with

Anxiety scores (HADS–A) ⱖ8 are diagnosed with anxiety

METHOD disorders (sensitivity: 0.89; specificity: 0.75), and patients

with depression scores (HADS–D) ⱖ8 are diagnosed with

Study Population depression disorders (sensitivity: 0.80; specificity: 0.88).26

This study enrolled 200 patients, age ⱖ18 years, on The Short-Form Health-Related Quality of Life Scale (SF–

hemodialysis at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Keelung, 36) The SF–36 assesses eight dimensions of physical

between 2007 and 2009. Written informed consent was and mental health. The score range is 100 (optimal) to 0

obtained from each patient before participation. This study (poorest). The eight subscales are the following: physical

Psychosomatics 51:6, November-December 2010 http://psy.psychiatryonline.org 528.e1

Depression and Suicide in Hemodialysis

functioning (PF); physical role-functioning (RP); bodily men, and 106 (53.0%) were women. Of the 200 subjects,

pain (BP); general health (GH); vitality (VT); social func- 47 (23.5%) fulfilled DSM–IV criteria for a major depres-

tioning (SF); emotional role-functioning (RE); and mental sive disorder, and 43 (21.5%) reported having suicidal

health (MH).27 A standard scoring algorithm aggregates ideation within the past month. Of the 43 patients with

scores from the eight SF–36 subscales into two summary suicidal ideation, 27(62.8%) fulfilled the DSM–IV criteria

scores for the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and for major depressive disorder; 16 (37.2%) did not. The

Mental Component Summary (MCS).28 The SF–36 has mean HADS–D score for all 200 patients was 6.5 (5.6);

demonstrated sensitivity to change, and score changes can range: 0 –21; 70 patients (35%) had depressive disorders

be interpreted as changes in the health-related quality of (HADS–D score ⱖ8), and 42 patients (21.0%) had anxiety

life of patients. symptoms. Table 1 summarizes the demographic charac-

teristics of depressed and nondepressed patients, catego-

The Chalder Fatigue Scale (CFS) Fatigue symptoms rized using the ⱖ8 cutoff point of the HADS–D scale.

were evaluated with the self-report CFS.29 This scale con- There was no significant difference in gender ratio, age,

sists of 11 items covering the physical and mental aspects education, duration of hemodialysis, smoking, or alcohol

of fatigue. Item responses are on a 4-point Likert scale. drinking history between the depressed and nondepressed

Total fatigue score, which is obtained by adding the scores groups. Compared with nondepressed patients, patients’

for all 11 items, has a range of 0 –33. The CFS has a high depression was significantly associated with low BMI and

degree of internal consistency, with a Cronbach ␣ of 0.89. number of comorbid physical illnesses.

Principal-component analysis supports the use of a two-

Table 2 shows the psychological characteristics of

factor solution (Physical Fatigue and Mental Fatigue).29

suicidality, anxiety, fatigue, and quality of life for de-

pressed and nondepressed patients. Among the subjects,

Statistical Analysis there was no significant difference in the rate of suicide

attempts in their lifetime between the depressed and non-

Data were analyzed with SPSS Version 16 statistical depressed patients, and no patient had had a suicide at-

software. Variables are presented as mean ⫾ standard tempt within the past month. The depressed patients had

deviation (SD) or frequency. An HADS score ⱖ8 is the significantly more suicidal ideation and suicide plans and

dichotomous cutoff for significant depression or anxiety had a higher incidence of anxiety disorders than nonde-

symptoms. Descriptive statistics were analyzed by inde- pressed patients. Moreover, depressed patients had signif-

pendent t-test and paired t-test; metric variables were an- icantly higher scores on the HADS–D, HADS–A, and

alyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); and 2 CFS, and significantly lower scores for all dimensions of

test and Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical vari- the SF–36 than nondepressed patients.

ables. The Mann-Whitney test and Wilcoxon signed-ranks The correlations between suicidal ideation and HADS

test were also applied to metric variables when the data scores for the Depression and Anxiety scales, CFS scores,

distribution violated parametric assumptions. Partial cor-

and the PCS and MCS of the SF–36 are shown in Table 3.

relation was used to analyze the relationships among sui-

After controlling for BMI and number of comorbid

cide risk, and HADS, SF–36, and CFS scores, while con-

physical illnesses, suicidal ideation and scores on the

trolling for body mass index (BMI) and number of

HADS Depression and Anxiety scales and CFS were

comorbid physical illnesses. Structural-equation model-

positively and strongly correlated. Scores on the SF–36

ing, using maximum-likelihood estimation, was further

PCS were positively and strongly correlated with the

utilized to analyze the strength of variable relationships

SF–36 MCS, and both were negatively correlated with

among depression, anxiety, fatigue, quality of life, and

suicidal ideation and scores on the HADS Depression

suicide risk. All tests were two-tailed, and the level of

and Anxiety scales and the CFS.

significance was p ⬍0.05.

Significant and mutual correlations existed between

fatigue, depression, anxiety, and quality of life. Structural-

RESULTS equation modeling revealed that depression (⫽0.34; p

⬍0.001) and anxiety (⫽0.31; p ⬍0.001) had a significant

Mean age of the 200 patients on hemodialysis in this study direct relationship with suicidal ideation, whereas fatigue

was 58.6 (13.9) years. Of all patients, 94 (47.0%) were and quality of life did not.

528.e2 http://psy.psychiatryonline.org Psychosomatics 51:6, November-December 2010

Chen et al.

DISCUSSION gested as plausible explanations for this epidemiological

phenomenon.31 Interestingly, the correlation between BMI

Study results demonstrate that depression was correlated and survival rate was noted among most ethnic groups,

with low BMI and a high number of comorbid physical with the exception of Asians.30 Analytical results obtained

illnesses. Depressed patients had a significantly higher by this study demonstrate that depressed patients had

incidence of anxiety and fatigue, more common suicidal lower BMIs than nondepressed patients. Loss of appetite

ideation, and significantly lower quality of life than non- and decreased body weight are common manifestations of

depressed patients. The intercorrelations between fatigue, depression. Thus, the causal relationships among low

depression, anxiety, and quality of life were significant. BMI, depression, and mortality warrant further investiga-

Suicidal ideation was strongly related to depression and tion.

anxiety, but not to fatigue or quality of life. Empirically, patients with many comorbid physical

A high BMI is associated with increased survival rate illnesses have worse physical condition and greater psy-

and reduced risk of hospitalization for hemodialysis pa- chological stress than those with few comorbid physical

tients.30,31 Poor nutrition and inflammation have been sug- illnesses. Our results also demonstrate that depression was

TABLE 1. Demographic Characteristics of Depressed and Non-Depressed Hemodialysis Patients

Characteristic Total (Nⴝ200) Non-Depressed (Nⴝ130) Depressed (Nⴝ70) p

Gender (men/women), N (%) 94/106 (47.0/53.0) 56/74 (43.1/56.9) 38/32 (54.3/45.7) NS

Smoking, N (%) 36 (18.8) 19 (15.3) 17 (25.0) NS

Alcohol use, N (%) 22 (11.5) 10 (8.1) 12 (17.6) 0.058

Age, years a 58.6 (13.9) 58.5 (13.3) 58.8 (15.0) NS

Education, years a 7.1 (4.6) 7.3 (4.4) 6.6 (4.8) NS

Body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) a 23.3 (4.0) 24.0 (4.7) 20.3 (2.8) ⬍0.001

a

Comorbidity, physical illnesses, N 2.0 (1.6) 1.8 (1.4) 2.4 (1.8) 0.018

Hemodialysis duration, months a 68.1 (65.8) 67.1 (64.1) 69.7 (69.5) NS

Depression was defined as a Hospital Anxiety and Depression Rating Scale (HADS–D) score ⱖ8.

a

Mean (standard deviation).

TABLE 2. Psychological Characteristics of Depressed and Non-Depressed Hemodialysis Patients

Characteristic Non-Depressed (Nⴝ130) Depressed (Nⴝ70) p

Suicidality, N (%)

Suicidal ideation, past month 8 (6.2) 35 (50.0) ⬍0.001

Suicide plan, past month 1 (0.8) 6 (8.6) 0.008

Suicide attempt, lifetime 2 (1.5) 5 (7.1) 0.052

HADS–Anxiety score 3.0 (2.9) 7.7 (4.3) ⬍0.001

HADS–Depression score 2.9 (2.2) 13.2 (3.5) ⬍0.001

Fatigue score 17.0 (4.2) 24.7 (5.5) ⬍0.001

Health-Related Quality of Life

Physical Functioning 67.2 (23.2) 44.1 (34.0) ⬍0.001

Physical Role Functioning 71.9 (40.0) 34.6 (43.3) ⬍0.001

Emotional Role Functioning 87.1 (31.0) 36.2 (42.8) ⬍0.001

Vitality 60.8 (18.3) 29.1 (14.9) ⬍0.001

Mental Health 79.8 (13.7) 42.4 (17.1) ⬍0.001

Social Functioning 81.9 (22.9) 59.3 (24.8) ⬍0.001

Bodily Pain 76.2 (22.5) 59.3 (24.8) ⬍0.001

General Health 52.0 (24.0) 23.2 (16.0) ⬍0.001

Physical Component 57.9 (25.1) 39.6 (27.0) ⬍0.001

Summary

Mental Component Summary 81.9 (18.4) 36.8 (22.7) ⬍0.001

Depression was defined as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Rating Scale (HADS–D) ⱖ8.

Values are mean (standard deviation), unless otherwise indicated.

Psychosomatics 51:6, November-December 2010 http://psy.psychiatryonline.org 528.e3

Depression and Suicide in Hemodialysis

TABLE 3. Correlation of Suicide Risk, Depression, Anxiety, Fatigue, and Health-Related Quality of Life, Controlling for Body Mass

Index (BMI) and Number of Comorbid Physical Illnesses

Suicide Risk Depression Anxiety Fatigue PCS MCS

Suicide risk —

Depression 0.46*** —

Anxiety 0.46*** 0.59*** —

Fatigue 0.37*** 0.68*** 0.58*** —

PCS –0.19** –0.35*** –0.39*** –0.54*** —

MCS –0.39*** –0.77*** –0.62*** –0.63*** 0.21** —

PCS: Physical Component Summary of Health-Related Quality of Life; MCS: Mental Component Summary of Health-Related Quality of Life.

*

p⬍0.05; ** p⬍0.01; *** p⬍0.001.

significantly correlated with the number of comorbid isted between fatigue, depression, anxiety, and quality of

physical illnesses. The comorbidity score of a major co- life. This finding is generally compatible with those in the

morbid physical disease has been demonstrated to be a literature.

predictor of mortality in general-medical inpatients.32 Anxiety is also common in hemodialysis patients,39

In this study, 23.5% of patients had a major depres- and a high rate (20%) of comorbid depression and anxiety

sive disorder as defined by DSM–IV criteria. To meet the was noted during a follow-up study.11 Those with a per-

diagnostic DSM–IV criteria for major depressive disorder, sistent course of depression had marked decreases in qual-

the subjects needed to fulfill the exclusion criteria “symp- ity of life and self-reported health status; however, this

toms are not due to the direct physiological effects of a pattern did not emerge with an anxiety diagnosis.11 In this

medication or a general medical condition.” Therefore, a study, 15.5% of subjects had comorbid depression and

substantial proportion of subjects who met the criteria for anxiety, and 44.3% of depressed patients had comorbid

“depressive disorders” defined by HADS–D scores ⱖ8 did anxiety. Furthermore, anxiety is also a factor strongly

not meet DSM–IV criteria for major depressive disorder. correlated with suicidal ideation. Uncertainty regarding

Some studies indicated that moderate depressive syn- the future and fear of losing control in life are important

dromes are common in roughly 25% of ESRD patients, factors associated with anxiety that adversely affect emo-

and major depression is common in 5%–22% of ESRD tional stability.22 The importance of anxiety may have

patients.32,33 The etiology of dialysis-related depression is been underestimated for hemodialysis patients. Notably,

multifactorial, and is related to biological, psychological, anxiety is a common psychological problem that may

and social mechanisms.3 Biological mechanisms include emerge during the initial course of dialysis;11 thus, it is

increased cytokine levels,1 possible genetic predisposi- important to identify anxiety symptoms in dialysis pa-

tion,34 and neurotransmitters affected by uremia.35 Psy- tients.

chological and social factors include feelings of hopeless- Improved quality of life is correlated with high

ness, perceptions of loss and lack of control, job loss, and self-esteem and low levels of mood disturbances.17 De-

altered family and social relationships.1,34 Depression is a creased health-related quality of life is strongly corre-

significant factor influencing survival9 and is strongly cor- lated with depression, anxiety,39 –41 and increased mor-

related with fatigue, anxiety, quality of life, and suicide. tality in hemodialysis patients.8,17 Poor exercise

Fatigue can be a debilitating symptom for patients under- tolerance and muscle weakness may limit daily activity,

going hemodialysis, and it is strongly correlated with de- further resulting in poor quality of life.5,42 Depression

pression.36 The pathogenesis of fatigue among hemodial- scores were independently correlated with all SF–36

ysis patients has been attributed to osmotic disequilibrium, dimensions.18 Nevertheless, composite scores for all

change in blood pressure, intramuscular energy metabo- eight SF–36 subscales were aggregated into the PCS

lism, and central activation failure.13,37 Fatigue is not only and MCS. The MCS had a stronger correlation with

strongly correlated with scores for many SF–36 subscales, depression than did the PCS.8 Although our results

but it is strongly correlated with dialysis patient survival.38 showed that the correlation coefficient between depres-

Fatigue and depression may be closely related, and de- sion and the MCS (– 0.77) was higher than that for

pression may manifest as feelings of tiredness and lack of depression and the PCS (– 0.35), both were significant.

energy.13 In this study, significant mutual correlations ex- Fatigue, anxiety, depression, or reduced quality of life

528.e4 http://psy.psychiatryonline.org Psychosomatics 51:6, November-December 2010

Chen et al.

may be a primary response when a patient begins hemo- quality of life have been identified among hemodialysis

dialysis; nevertheless, suicide is undoubtedly an adverse patients.46 It was postulated that Asian patients perceive

consequence.22 The suicide rate of ESRD patients was kidney disease as a social burden.46 Perceived “burden-

approximately 15 times greater than that for the general someness” has been reported to be correlated with suicidal

United States population. Suicide was associated with sev- ideation.47,48 Whether Asian hemodialysis patients per-

eral demographic characteristics.20 A preexisting anxiety ceive their illness as a greater burden to their family or

disorder was identified as an independent risk factor for society than other ethnic populations do, and whether this

subsequent onset of suicidal ideation and attempts.43 De- could account for the high incidence of suicidal ideation in

pression is also a prominent predictor for suicide for many this population are areas for further study. We would

chronic illnesses.20,44 Results of this study revealed a sig- recommend further research with samples from multiple

nificant direct effect for depression and anxiety on suicidal sites and other ethnicities to improve generalization.

ideation. Although this cross-sectional design could not deter-

Several limitations of this study must be considered. mine causal relationships, this study provides a path-anal-

First, this is an observational, cross-sectional study. The ysis for the complex relationships between depression,

causal inferences of fatigue, anxiety, depression, and re- anxiety, fatigue, quality of life, and suicide risk in hemo-

duced quality of life remain unclear. Second, the Charlson dialysis patients. In conclusion, depressed hemodialysis

Comorbidity Index,45 which been shown to be an effective patients had greater levels of fatigue and anxiety, greater

measure of comorbidity severity, was not computed for suicide risk, and poorer quality of life than nondepressed

patients in this study. Third, diagnosing depressive disor- patients. In this population, depression was associated

ders or anxiety disorders is difficult for hemodialysis pa- with a low BMI and an increased number of comorbid

tients when we apply DSM–IV criteria. To meet the diag- physical illnesses. Depression and anxiety were robust

nostic DSM–IV criteria for major depressive disorder or indicators of suicide risk. Depressed and anxious patients

anxiety disorders, the subjects need to fulfill the exclusion should be identified early and offered appropriate treat-

criterion “The symptoms are not due to the direct physi- ment. A prospective, controlled study will prove helpful in

ological effects of a medication or a general medical con- determining whether early detection and early intervention

dition.” It is difficult to judge arbitrarily whether the de- of comorbid depression and anxiety among hemodialysis

pressive symptoms are due to the direct physiological patients will reduce their suicide risk.

effects of a medication or a general medical condition in

hemodialysis patients. The DSM–IV criteria may have a

higher specificity but a lower sensitivity than the HADS. The authors express their deepest gratitude to all the

Therefore, the authors used the HADS to define caseness patients who participated in this study.

of depressive disorders and anxiety disorders. Last, sub- We thank Ted Knoy for his editorial assistance.

jects in this study were from a single site. Hence, the This study was supported by the National Science

external validity may be limited. Ethnic differences in Council, Taiwan (NSC 96 –2314-B-182A-090-MY2).

References

1. Kimmel PL: Psychosocial factors in dialysis patients. Kidney Int individual survival on chronic renal hemodialysis: a two-year

2001; 59:1599 –1613 follow-up, I. Psychosom Med 1973; 35:64 – 82

2. Reiss D: Patient, family, and staff responses to end-stage renal 8. Drayer RA, Piraino B, Reynolds CF 3rd, et al: Characteristics of

disease. Am J Kidney Dis 1990; 15:194 –200 depression in hemodialysis patients: symptoms, quality of life,

3. Chilcot J, Wellsted D, Da Silva-Gane M, et al: Depression on and mortality risk. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2006; 28:306 –312

dialysis. Nephron Clin Pract 2008; 108:256 –264 9. Kimmel PL, Weihs K, Peterson RA: Survival in hemodialysis

4. Kuo HW, Tsai SS, Tiao MM, et al: Epidemiological features of patients: the role of depression. J Am Soc Nephrol 1993; 4:12–27

CKD in Taiwan. Am J Kidney Dis 2007; 49:46 –55 10. Cukor D, Coplan J, Brown C, et al: Depression and anxiety in

5. Hsieh RL, Lee WC, Huang HY, et al: Quality of life and its urban hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;

correlates in ambulatory hemodialysis patients. J Nephrol 2007; 2:484 – 490

20:731–738 11. Cukor D, Coplan J, Brown C, et al: Course of depression and

6. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al: Cross-national anxiety diagnosis in patients treated with hemodialysis: a 16-

epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA month follow-up. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 3:1752–1758

1996; 276:293–299 12. Lee KA, Hicks G, Nino-Murcia G: Validity and reliability of a

7. Foster FG, Cohn GL, McKegney FP: Psychobiologic factors and scale to assess fatigue. Psychiatry Res 1991; 36:291–298

Psychosomatics 51:6, November-December 2010 http://psy.psychiatryonline.org 528.e5

Depression and Suicide in Hemodialysis

13. Jhamb M, Weisbord SD, Steel JL, et al: Fatigue in patients 31. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Abbott KC, Salahudeen AK, et al: Survival

receiving maintenance dialysis: a review of definitions, mea- advantages of obesity in dialysis patients. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;

sures, and contributing factors. Am J Kidney Dis 2008; 52:353– 81:543–554

365 32. Herrmann-Lingen C, Klemme H, Meyer T: Depressed mood,

14. Lee BO, Lin CC, Chaboyer W, et al: The fatigue experience of physician-rated prognosis, and comorbidity as independent pre-

haemodialysis patients in Taiwan. J Clin Nurs 2007; 16:407– 413 dictors of 1-year mortality in consecutive medical inpatients.

15. Tsay SL, Healstead M: Self-care, self-efficacy, depression, and J Psychosom Res 2001; 50:295–301

quality of life among patients receiving hemodialysis in Taiwan. 33. Cohen LM, Dobscha SK, Hails KC, et al: Depression and sui-

Int J Nurs Stud 2002; 39:245–251 cidal ideation in patients who discontinue the life-support treat-

16. Evans RW, Manninen DL, Garrison LP Jr, et al: The quality of ment of dialysis. Psychosom Med 2002; 64:889 – 896

life of patients with end-stage renal disease. N Engl J Med 1985; 34. Israel M: Depression in dialysis patients: a review of psycholog-

312:553–559 ical factors. Can J Psychiatry 1986; 31:445– 451

17. Wolcott DL, Nissenson AR, Landsverk J: Quality of life in

35. Smogorzewski M, Ni Z, Massry SG: Function and metabolism of

chronic dialysis patients: factors unrelated to dialysis modality.

brain synaptosomes in chronic renal failure. Artif Organs 1995;

Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1988; 10:267–277

19:795– 800

18. Kao TW, Lai MS, Tsai TJ, et al: Economic, social, and psycho-

36. Sklar AH, Riesenberg LA, Silber AK, et al: Postdialysis fatigue.

logical factors associated with health-related quality of life of

Am J Kidney Dis 1996; 28:732–736

chronic hemodialysis patients in northern Taiwan: a multicenter

study. Artif Organs 2009; 33:61– 68 37. Johansen KL, Doyle J, Sakkas GK, et al: Neural and metabolic

19. Harris EC, Barraclough BM: Suicide as an outcome for medical mechanisms of excessive muscle fatigue in maintenance hemo-

disorders. Medicine (Baltimore) 1994; 73:281–296 dialysis patients. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2005;

20. Kurella M, Kimmel PL, Young BS, et al: Suicide in the United 289:R805–R813

States end-stage renal disease program. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005; 38. Jhamb M, Argyropoulos C, Steel JL, et al: Correlates and out-

16:774 –781 comes of fatigue among incident dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc

21. Bronisch T, Wittchen HU: Suicidal ideation and suicide at- Nephrol 2009; 4:1779 –1786

tempts: comorbidity with depression, anxiety disorders, and sub- 39. Kring DL, Crane PB: Factors affecting quality of life in persons

stance abuse disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994; on hemodialysis. Nephrol Nurs J 2009; 36:15–24

244:93–98 40. Son YJ, Choi KS, Park YR, et al: Depression symptoms and the

22. Haenel T, Brunner F, Battegay R: Renal dialysis and suicide: quality of life in patients on hemodialysis for end-stage renal

occurrence in Switzerland and in Europe. Compr Psychiatry disease. Am J Nephrol 2009; 29:36 – 42

1980; 21:140 –145 41. Perlman RL, Finkelstein FO, Liu L, et al: Quality of life in

23. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al: The Mini-Inter- chronic kidney disease (CKD): a cross-sectional analysis in the

national Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development Renal Research Institute CKD study. Am J Kidney Dis 2005;

and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for 45:658 – 666

DSM–IV and ICD–10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 20):22– 42. Sakkas GK, Sargeant AJ, Mercer TH, et al: Changes in muscle

33; Quiz: 34 –57 morphology in dialysis patients after 6 months of aerobic exer-

24. Ritchie K, Artero S, Beluche I, et al: Prevalence of DSM–IV cise training. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18:1854 –1861

psychiatric disorder in the French elderly population. Br J Psy- 43. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al: Anxiety disorders and risk for

chiatry 2004; 184:147–152 suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: a population-based, lon-

25. Kuo CJ, Tang HS, Tsay CJ, et al: Prevalence of psychiatric

gitudinal study of adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:1249 –

disorders among bereaved survivors of a disastrous earthquake in

1257

Taiwan. Psychiatr Serv 2003; 54:249 –251

44. Hietanen P, Lonnqvist J: Cancer and suicide. Ann Oncol 1991;

26. Olsson I, Mykletun A, Dahl AA: The Hospital Anxiety and

2:19 –23

Depression Scale: a cross-sectional study of psychometrics and

45. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al: A new method of

case-finding abilities in general practice. BMC Psychiatry 2005;

5:46 classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: de-

27. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item Short-Form velopment and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40:373–383

Health Survey (SF–36), I: conceptual framework and item se- 46. Bakewell AB, Higgins RM, Edmunds ME: Does ethnicity influ-

lection. Med Care 1992; 30:473– 483 ence perceived quality of life of patients on dialysis and follow-

28. Taft C, Karlsson J, Sullivan M: Do SF–36 summary component ing renal transplant? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001; 16:1395–

scores accurately summarize subscale scores? Qual Life Res 1401

2001; 10:395– 404 47. Brown RM, Brown SL, Johnson A, et al: Empirical support for

29. Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, et al: Development of an evolutionary model of self-destructive motivation. Suicide

a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res 1993; 37:147–153 Life Threat Behav 2009; 39:1–12

30. Johansen KL, Young B, Kaysen GA, et al: Association of body 48. Davidson CL, Wingate LR, Rasmussen KA, et al: Hope as a

size with outcomes among patients beginning dialysis. Am J Clin predictor of interpersonal suicide risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav

Nutr 2004; 80:324 –332 2009; 39:499 –507

528.e6 http://psy.psychiatryonline.org Psychosomatics 51:6, November-December 2010

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Pid 5Document23 paginiPid 5basti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Renato Anghinah, Wellingson Paiva, Linamara Rizzo Battistella, Robson Amorim - Topics in Cognitive Rehabilitation in The TBI Post-Hospital Phase-Springer International Publishing (2018)Document129 paginiRenato Anghinah, Wellingson Paiva, Linamara Rizzo Battistella, Robson Amorim - Topics in Cognitive Rehabilitation in The TBI Post-Hospital Phase-Springer International Publishing (2018)basti_aka_slim0% (1)

- Wca HandbookDocument254 paginiWca Handbookbasti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental RFC PDFDocument4 paginiMental RFC PDFbasti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stefano 2012Document9 paginiStefano 2012basti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Iom 2015 SVT Report FullDocument211 paginiIom 2015 SVT Report Fullbasti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pid 5Document23 paginiPid 5basti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

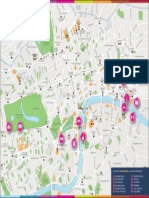

- London Tourist MapDocument1 paginăLondon Tourist MapAmber RileyÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Classifications by Cancer Sites With Sufficient or Limited Evidence in Humans, Volumes 1 To 122Document12 paginiList of Classifications by Cancer Sites With Sufficient or Limited Evidence in Humans, Volumes 1 To 122Pod ADÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pid 5Document23 paginiPid 5basti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thinkpad 11e Yoga 11e Ug enDocument162 paginiThinkpad 11e Yoga 11e Ug enbasti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neuropsychiatric Inventory-An Easy To Use Tool To UnderstandDocument46 paginiNeuropsychiatric Inventory-An Easy To Use Tool To Understandbasti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

- London Tourist MapDocument4 paginiLondon Tourist Mapbasti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dell Inspiron 3567Document27 paginiDell Inspiron 3567basti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smart Goals PDFDocument6 paginiSmart Goals PDFAndreea TeodoraÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 B978012800977200005X MainDocument35 pagini1 s2.0 B978012800977200005X MainM LyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workaholism A Review PDFDocument18 paginiWorkaholism A Review PDFbasti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Swot Analysis WorksheetDocument1 paginăSwot Analysis Worksheetbasti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smart Goals PDFDocument6 paginiSmart Goals PDFAndreea TeodoraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Latest Journal Impact 2016 Released in 2017Document253 paginiLatest Journal Impact 2016 Released in 2017Maaz NasimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Incorporation of A Psychologist Into A Nephrology PDFDocument7 paginiIncorporation of A Psychologist Into A Nephrology PDFbasti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Depressive Symptoms and Dietary Adherence in Patients With End-Stage Renal DiseaseDocument10 paginiDepressive Symptoms and Dietary Adherence in Patients With End-Stage Renal Diseasebasti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bayesian TutorialDocument76 paginiBayesian TutorialMárcio Pavan100% (3)

- Realigning DietDocument9 paginiRealigning Dietbasti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fatigue Severity ScaleDocument1 paginăFatigue Severity ScaleAffuadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Qolibri QuestionaireDocument2 paginiQolibri Questionairebasti_aka_slim100% (2)

- Dinsdale 2013Document25 paginiDinsdale 2013basti_aka_slimÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Treatments That Work) Mark P. Jensen-Hypnosis For Chronic Pain Management - Workbook-Oxford University Press, USA (2011) PDFDocument160 pagini(Treatments That Work) Mark P. Jensen-Hypnosis For Chronic Pain Management - Workbook-Oxford University Press, USA (2011) PDFbasti_aka_slim100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Homicides by Sharp WeaponsDocument49 paginiHomicides by Sharp WeaponsSarvjeet TomerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acid and Burns Violence in Nepal: A Situational AnalysisDocument30 paginiAcid and Burns Violence in Nepal: A Situational AnalysisSuman RegmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- DNB Vol34 No4 706 PDFDocument9 paginiDNB Vol34 No4 706 PDFEmir BegagićÎncă nu există evaluări

- SM Suppl. MaterialDocument9 paginiSM Suppl. MaterialPatricia Martínez piano flamencoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental Wellbeing and Substance Use Among Youth of ColourDocument75 paginiMental Wellbeing and Substance Use Among Youth of ColourthemoohknessÎncă nu există evaluări

- Life Over Knife: by G-Yan MamuyacDocument10 paginiLife Over Knife: by G-Yan MamuyacJushua Mari Lumague DiazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Suicide in Teenagers 2001Document6 paginiSuicide in Teenagers 2001Simpson KhooÎncă nu există evaluări

- Volume 77 Issue 6Document24 paginiVolume 77 Issue 6The RetortÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effect of Substance Abuse Among Youths of Ugwan Rana - Madam SusieDocument68 paginiThe Effect of Substance Abuse Among Youths of Ugwan Rana - Madam SusieDemsy Audu100% (1)

- Understanding Suicidal Ideation With The Beck Scale For Suicide IdeationzymgqDocument5 paginiUnderstanding Suicidal Ideation With The Beck Scale For Suicide Ideationzymgqcarbonvacuum92Încă nu există evaluări

- Star Comprehensive BrochureDocument1 paginăStar Comprehensive BrochureShakti ShivanandÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of Suicide Methods and Substances InfluencingDocument12 paginiAnalysis of Suicide Methods and Substances InfluencingPastel NekoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental Health AwarenessDocument20 paginiMental Health AwarenessFlordeliza Manaois RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental Health Care in India: Old Aspirations Renewed HopeDocument973 paginiMental Health Care in India: Old Aspirations Renewed HopeVaishnavi JayakumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- First Aid For Mental Health - Tutor NotesDocument41 paginiFirst Aid For Mental Health - Tutor NotesJASON SANDERS100% (2)

- GBD Report 2004update Part4 PDFDocument14 paginiGBD Report 2004update Part4 PDFPrachi GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Buddhist Views On Marriage PDFDocument3 paginiBuddhist Views On Marriage PDFlaloo01100% (1)

- Samaritans Wales Strategy (English-Welsh)Document16 paginiSamaritans Wales Strategy (English-Welsh)debshol5948Încă nu există evaluări

- Biathanatos CompleteTextDocument200 paginiBiathanatos CompleteTextJacqueskikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effectiveness of Interventions To Prevent Suicide and Suicidal Behaviour - A Systematic Review - 2008Document248 paginiEffectiveness of Interventions To Prevent Suicide and Suicidal Behaviour - A Systematic Review - 2008ixmayorgaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 7: Mood Disorders and SuicideDocument41 paginiChapter 7: Mood Disorders and SuicideEsraRamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nursing Care Plan Borderline PD (Client A) NCP #1: Pia Mae D. Buaya N-31Document9 paginiNursing Care Plan Borderline PD (Client A) NCP #1: Pia Mae D. Buaya N-31Pia Mae BuayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Saving Military FamiliesDocument6 paginiSaving Military Familieseemtrader100% (1)

- English Term PaperDocument14 paginiEnglish Term PaperLouise Mikhaela Rose EscarrillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Suicide EssayDocument4 paginiSuicide EssayTiffanyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Momentum Mozambique Brochure July 2014Document12 paginiMomentum Mozambique Brochure July 2014Paulo FilimoneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Report On Mental Health Issue in SchoolDocument10 paginiReport On Mental Health Issue in SchoolPadam PandeyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Suicide Prevention Centre - NewsDocument4 paginiSuicide Prevention Centre - NewsThomas CherianÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Wolaita Sodo City Omo Sheleko DistrictDocument5 paginiIn Wolaita Sodo City Omo Sheleko DistrictDaniel AlemayehuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shako, Kay. Sociodemographic Factors Culture and Suicide in GuyanaDocument93 paginiShako, Kay. Sociodemographic Factors Culture and Suicide in GuyanaMarcela FranzenÎncă nu există evaluări