Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Landscape M Study

Încărcat de

palaniTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Landscape M Study

Încărcat de

palaniDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/232607158

Landscape Plant Material, Size, and Design Sophistication Increase Perceived

Home Value

Article · October 2005

CITATIONS READS

31 5,319

14 authors, including:

Bridget K. Behe Susan Barton

Michigan State University University of Delaware

181 PUBLICATIONS 1,433 CITATIONS 25 PUBLICATIONS 126 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Rodney Thomas Fernandez Charles R. Hall

Michigan State University Texas A&M University

97 PUBLICATIONS 1,218 CITATIONS 150 PUBLICATIONS 921 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Clean WateR3: Reduce, Remediate, Recycle - Enhancing Alternative Water Resources Availability and Use to Increase Profitability in Specialty Crops View project

Blueberry Pollination View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Bridget K. Behe on 03 June 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Landscape Plant Material, Size, and Design Sophistication

Increase Perceived Home Value1

B. Behe2, J. Hardy2, S. Barton3, J. Brooker4, T. Fernandez2, C. Hall4, J. Hicks2,

R. Hinson5, P. Knight6, R. McNiel7, T. Page8, B. Rowe2, C. Safley9, and R. Schutzki2

Department of Horticulture, Michigan State University

East Lansing, MI 48824

Abstract

Little consumer research is available to help landscape design and installation businesses develop service marketing strategies. We

investigated the effect of three components of a landscape design on the perceived value of a home. This information would be useful

in marketing lawn and landscape services to prospective clients. Our objective was to provide a consumer perspective on the value of

the components in a ‘good’ landscape and determine which attributes of a landscape consumers valued most. Using conjoint design,

1323 volunteer participants in seven states viewed 16 photographs that depicted the front of a landscaped residence. Landscapes were

constructed using various levels of three attributes: plant material type, design sophistication, and plant size. Results showed that the

relative importance increased from plant material type to plant size to design sophistication. Across all seven markets, study participants

perceived that home value increased from 5% to 11% for homes with a good landscape.

Index words: conjoint analysis, consumer, marketing.

Significance to the Nursery Industry the seven states, plant material type was relatively least im-

While realtors and realty-related Websites can provide in- portant. Plant size was of intermediate importance in all

formation to homeowners regarding the amount of a home markets analyzed here, but was most important in results

improvement that can be recovered upon the sale of a home, previously published (18). Still, the largest affordable plant

there is insufficient information available as to the value of size should be used as it consistently provided a higher per-

landscaping as a home improvement across multiple mar- ceived value in all markets. Landscape professionals should

kets. Specifically, how much do plant size, plant material indicate the type of plants used in a landscape, but realize

type, and design sophistication in a landscape affect the per- that potential clients will not likely value this as much as

ceived value of a home? If these questions were answered, design sophistication and plant size. Professional landscape

landscape professionals would have more information to mangers can show potential clients that a good landscape

present to potential clients on the soundness of an invest- adds 5 to 11% to the perceived value of a home.

ment in landscape services. Our objective was to provide a

consumer perspective on the value of the components in a Introduction

‘good’ landscape and determine which landscape attributes Gardening leads the nation as the leisure activity in which

consumers valued most, and to see if that was consistent more Americans participate than any other (6). For garden-

across markets. Overall, participants valued the landscape ers, a general profile emerged from the literature showing

design sophistication most. Landscape professionals should individuals who were highly involved with gardening or those

emphasize to customers that island beds and curved bed lines who spent large amounts of money on gardening were more

add to the perceived value of a home. Results showed that in likely to be female and older, wealthier, and more educated

than average (4, 18). Higher average home value was an-

other important characteristic of an avid gardener (18). In

1

Received for publication February 11, 2005; in revised form April 18, 2005. another study, primary purchasers of nursery plants ranged

Partial funding was provided by a grant from The Horticultural Research in age from 25 to 44 years, with a higher than average in-

Institute, 1000Vermont Ave., NW., Suite 360, Washington, DC, 20005. come and level of education (17). Yet, gardening can be an

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of many colleagues in activity in which participants are active or passive. Active

the USDA multi-state S-290 project for their assistance in data collection

and manuscript revisions.

participants may choose to ‘do-it-yourself’ while passive

2

Department of Horticulture, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI

participants may elect to have someone provide services of

48824. landscape design, installation, and maintenance.

3

Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, University of Delaware, Newark, The profile of the ‘typical’ landscape service buyer can be

DE 19716. gleaned from The National Gardening Survey (9). The aver-

4

Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Tennessee, Knox- age purchasers of landscape installations were 50 years of

ville, TN 37996. age or older, college educated, with a household income of

5

Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness, Louisiana State $75,000 or more. The American Nursery and Landscape As-

University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803. sociation conducted a consumer study, segmenting the mar-

6

Coastal Research and Extension Center, Mississippi State University, ket of landscape consumers into three categories: Partners,

Poplarville, MS 39470.

Pro-Purchasers, and Hardcore Do-it-Yourselfers (2). Partners

7

Department of Horticulture, University of Kentucky, Lexington KY 40546-

0091. preferred to work with landscape professionals on an ad-hoc

8

Department of Marketing and Supply Chain Management, Michigan State basis. The Hardcore Do-It-Yourselfers wanted to do most of

University, East Lansing, MI 48824. the work themselves and were not likely clients for profes-

9

Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, North Carolina State sional design and installation. Pro-Purchasers were the larg-

University, Raleigh, NC 27695. est group of customers and preferred no interaction with their

J. Environ. Hort. 23(3):127–133. September 2005 127

landscape jobs. This group consisted of single-family house- and definitions for each plan, and also received a set of guide-

holds with annual household incomes exceeding $100,000. lines that included incorporating only plants whose hardi-

Results showed that 22% of the Pro-Purchasers (2.8 million ness extended from USDA plant hardiness zones 4–7. Re-

households) were the most likely group to purchase profes- searchers did instruct the landscape designer to select plant

sional landscape services. Yet, there is little understanding material common across all hardiness zones to be included

of what these consumers want from a home landscape and in the study. Research on cross-national preferences for tree

what features of this highly personalized product are impor- canopy form showed that preferences for tree form were as-

tant to them. sociated with the tree shape reported as most common in the

The market for landscape design and installation is con- geographical area where the respondents grew up (32). The

siderably smaller than the market for plants and garden cen- architect was instructed to use only common plants that were

ter products. Butterfield (9) reported that less than 2.5% of readily available in all growing zones in the study. Computer

American homes used landscape design and 3.3% purchased generated color perspective images of the home and land-

installation services in 2003, percentages that have changed scaping were prepared from each flat plan [Adobe PhotoShop

little in the prior decade. Khatamian (25) reported that 9.5% version 5.0] (1). Each photograph depicted the home and land-

of those surveyed at garden centers, and flower, lawn and scaping as viewed from the street.

garden shows, preferred to contract with a professional in-

stallation firm. With approximately 109 million households Generation of orthogonal design, factor level definitions

in the United States in 2003, approximately two million may and conjoint analysis. Using the methodology of Hardy et

be potential targets for services. In the most recently avail- al. (18), the respondent’s overall preference for a particular

able statistics (1997), there were 37,853 landscape contrac- landscape was defined as the dollar value assigned to the

tors (SIC 0781-02) and 9826 landscape designers (SIC 0781- landscaped home by the respondent. Conjoint analysis was

03) (10). The relatively small size of this market and prolif- previously used in horticultural studies to assess relative

eration of firms willing to do this work suggests that much importance of attributes and predict consumer demand for

competition exists. blue geraniums (6) and colored bell peppers (15); investi-

Motivations for improving a home vary widely. For the gate consumer preference for packaging of edible flowers

resident of a newly constructed home, the exterior landscap- (24); and analyze consumer preference for retail evergreen

ing may serve as a ‘frame’ to the home, enhancing its aes- shrubs (13). Conjoint analysis defines overall preference for

thetics. For the resident desiring to sell a home, landscaping a particular product, in this case a landscape, as the sum of

could enhance market value. Realtors have data showing that the part-worths (also termed utilities) for each factor level

the value of a home is enhanced with the renovation of a (7, 16, 19). By definition, the sum of the part-worths is analo-

kitchen, bath, or bedroom, or with the addition of a deck or gous to the value added to the home by the landscape as pre-

patio. Realtors can also convey the return on investment for dicted by the conjoint analysis procedure. Researchers chose

renovations and additions. Recent estimates of recovered plant size, diversity of plant material (type), and design so-

costs show that 94% of a mid-priced bathroom addition can phistication as the factors that most comprehensively describe

be recovered, 74% of the cost of window replacement can be all landscape attributes. In this model, the preference for plant

recovered, and 79% of the cost of a family room addition size plus preference for design sophistication plus preference

can be recovered (12). for the type of plant material used resulted in the overall pref-

A Weyerhaeuser publication (3) estimated that landscap- erence (measured in dollars) for a particular landscape.

ing added approximately 15% from a homeowner perspec- For each factor, we determined a measurable, hierarchical

tive, but only 7.3% by real estate appraisers. Neither data set of levels for each variable. The plant size levels were

nor methodology were reported for arriving at the percent- defined as small, medium, or large. Small was the smallest

ages. Nearly all other studies of landscape value investigated available size for the product, large was the largest available

one attribute in a single market. Prior work by Hardy et al size for the product, and medium was the intermediate size

(18) added to the body of knowledge by showing that par- between large and small. Design sophistication levels were:

ticipants at a flower and garden show perceived the well- (1) foundation planting only, (2) foundation planting with

landscaped residence to increase in value by 12.7%. Plant one large, oblong island planting and one or two single speci-

size was most important in the conjoint analysis, followed men or shade trees in the lawn, or (3) a foundation planting

by design sophistication, and plant material. The 12.7% in- with adjoining beds and two or three large island plantings,

crease in home value was also consistent with several other all incorporating curved bedlines. The plant material types

reports (20, 21, 22, 28, 29, 31, 32). Given that most publica- were: (1) evergreen only, (2) evergreen and deciduous plants,

tions reported a 10–15% increase in perceived home value, (3) evergreen and deciduous plants with 20% of the visual

we hypothesized that a consistent and similar increase would area of the landscape beds planted in annual or perennial

be seen across in several markets. Using identical materials color, or (4) evergreen and deciduous plants, 20% annual or

and methodology from the Hardy et al. study (18), we ex- perennial color, and the addition of a colored brick sidewalk

pected that across all venues included, we would observe a entrance.

12% increase in perceived home value by the consumer. While all 36 (3 size × 3 design × 4 material levels) pos-

sible combinations of factor levels could have been used for

Materials and Methods full profile conjoint analysis, researchers chose to reduce

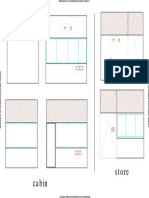

Generation of plans and photographs. A researcher pho- respondent fatigue by minimizing the number of photographs

tographed a two-story, newly-built home in a Delaware sub- evaluated. By using a partial factorial design, the number of

urb, as the test home. Given the researchers’ specifications, a photographs required to maintain orthogonality was reduced

commercially employed landscape architect prepared 16 flat from 36 to 16. Conjoint Designer [version 3.0 produced by

plans. The designer was given the factor level parameters Bretton-Clark, 1992] (7) was used to generate the list of 16

128 J. Environ. Hort. 23(3):127–133. September 2005

Fig. 1. Base home with no landscape.

stimuli. Conjoint and other statistical analyses were facili- per photograph included in the study. Given the anticipated

tated using SPSS 10.0 (25). standard deviation in change in perceived home value, a

sample size of 160 was expected to provide sufficient re-

Survey administration and instrument. Churchill and sponses to conduct the planned statistical analyses. The

Iancobucci (11) classify survey type by method of adminis- sample was a convenience sample, drawn to reflect perspec-

tration or data collection. While variations are possible, gen- tives of visitors to home and garden shows in seven markets

erally surveys are classified as telephone, mail, electronic who likely had an elevated interest in enhancing the value of

(email or Internet) and intercept. The latter refers to recruit- their home.

ing participants in a public setting, such as mall or other pub- Visitors were recruited to participate in the survey as they

lic venue. Lysaler (27) noted that mall-intercept interview- passed the display table on which the 16 photographs were

ing has increased substantially in use in the 1990s. While displayed. Participants were asked to examine a photograph

there is no one best method, each has applications and ad- of the survey home with only a lawn and a straight poured

vantages (11). Yet, several studies that use identical ques- cement walk and driveway (Fig. 1). They were told the home

tions by vary data collection indicate that respondents’ de- value, as estimated by local realtors in each market, and also

mographic characteristics and responses to questions are simi- the county in which the home was hypothetically located.

lar (8, 11, 14, 33). Several published studies used an inter- Researchers also stipulated in writing that the home was in a

cept technique for data collection to recruit potential respon- subdivision with similar new homes, and that the home was

dents from a variety of plant-related venues (5, 6, 10, 13, 23, a 4-bedroom, 2-1/2 bathroom two-story structure located on

26, 30). a half-acre lot (approximately 100 ft by 200 ft). Participants

Between April and July of 1999, surveys were adminis- were asked to look at the 16 additional photographs. Consid-

tered in seven markets throughout the eastern and central ering the price of the home assigned by realtors and the land-

United States: Delaware (DE), Kentucky (KY), Louisiana scaping and features around the homes, they were asked to

(LA), Mississippi (MS), North Carolina (NC), South Caro- assign a value to each home. The second part of the survey

lina (SC), and Texas (TX). Responses were collected at con- asked respondents to provide demographic information about

sumer home and garden shows. Responses from South Caro- themselves, their family, home, landscape and landscape ser-

lina were collected both at local garden center and a zoo. For vice usage. All questionnaires were identical in format.

each survey site, the same protocol was used for survey ma-

terials and the recruitment of participants. Multiple partici- Statistical methods. The overall conjoint analysis results

pants could self-administer the questionnaire simultaneously. were defined as the mean of the conjoint results generated

Researchers asked every second or third individual who for each respondent. Since this method of analysis allows for

passed the booth and expressed some interest (by making calculation of variance, typical tests of significance were

eye contact) if they would be willing to participate. This var- employed using SPSS 10.0 (34).

ied by time of day and pedestrian traffic at each location.

Researchers estimate mall intercept surveys achieve approxi- Results and Discussion

mately a 29% response rate, but this would be higher for Demographic profile of respondents. Female respondents

surveys in which the potential respondent has a high interest outnumbered male respondents in all states except North

(11). The sample size target was approximately 160 responses Carolina (Table 1). North Carolina had the youngest respon-

from each state, determined by having at least 10 responses dents with a mean average age of 40.4 years while Missis-

J. Environ. Hort. 23(3):127–133. September 2005 129

Table 1. Demographic characteristics showing means ± standard deviation of survey participants from seven states evaluating landscaped homes.

Survey Percent Age Education Persons in Per capita Hours spent Gardening

location (state) n female (years) (years) household income ($) in the garden expenditures ($)

Delaware 174 52.6 42.8 ± 12.4 14.7 ± 2.21 3.1 ± 1.4 28,198 ± 17,156 3.9 ± 6.8 771 ± 1,960

Kentucky 238 50.6 48.4 ± 11.0 16.0 ± 2.63 2.6 ± 1.1 34,361 ± 19,301 8.8 ± 10.3 2,327 ± 5,625

Louisiana 191 63.2 41.7 ± 7.7 16.0 ± 2.57 3.3 ± 1.4 28,231 ± 19,513 8.0 ± 12.8 800 ± ,997

Mississippi 199 65.7 48.4 ± 11.3 15.6 ± 2.58 2.7 ± 1.3 32,895 ± 18,632 9.8 ± 14.6 445 ± ,984

North Carolina 182 46.2 40.4 ± 11.4 15.7 ± 2.18 2.7 ± 1.1 29,480 ± 21,314 4.3 ± 5.7 1,508 ± 2,760

South Carolina 164 63.4 47.0 ± 12.8 15.8 ± 2.41 2.9 ± 1.3 29,280 ± 16,328 5.6 ± 5.5 1,861 ± 8,683

Texas 175 50.3 45.5 ± 13.0 15.9 ± 2.67 2.7 ± 1.1 28,906 ± 17,248 5.2 ± 5.2 902 ± 1,233

Total 1323 57.3 45.8 ± 12.1 15.8 ± 2.51 2.8 ± 1.2 31,903 ± 19,586 6.9 ± 9.2 1,409 ± 4,640

sippi and Kentucky had the oldest at a mean age of 48.4 years a better indicator of the average for each sample. The me-

(Table 1). Although over 99% of respondents in the Dela- dian hours ranged from 2.0 hours in Delaware to 9.8 hours in

ware sample stated they had finished at least 12 years of for- Mississippi. For the remaining states (KY, LA, NC, SC, TX)

mal education, they were the least educated group, with only the median time spent on lawn and garden ranged from 5 to

14.8% of the respondents completing formal education be- 6 hours.

yond high school. Mean household size varied from 3.3 The National Gardening Association (9) reported average

people in Louisiana to 2.6 people in Kentucky. Average per lawn and garden expenditures in 2003 were $457, up slightly

capita income ranged from $28,198 to $34,361 with no dif- from $452 in 1998. Respondents to the study spent from $445

ferences among states. (Mississippi) to $2327 (Kentucky) with a broad range of re-

The 2003 National Gardening Survey reported 84 million sponses, yet there were no statistically significant differences

households participated in lawn and gardening activities (9). among them.

Those more likely to participate in lawn and gardening ac-

tivities were married, ages 35–54 years, college educated, Model fit. Because the base price assigned to each home

have children, employed full-time with an annual income of reflected the local housing market, a direct comparison of

>$35,000. This sample averaged 57% female respondents, the dollar values predicted for various combinations of land-

whereas the National Gardening Survey sample had 52% scapes was inappropriate. We limited analysis to relative

female respondents. The average age was 45 years in this importance of factors and to the percentage increases in value

study which was the midpoint of the age range from the Na- for various factor levels over the base home value.

tional Gardening Survey. The average level of formal educa- Each of the individual conjoint models for each of the seven

tion completed by the respondents in this sample was nearly states explained at least 94% of the variance in respondent

16 years, equivalent to a college education. Forty-seven per- answers. In the context presented, plant size, design sophis-

cent of the National Gardening Survey sample had completed tication and plant material type were good indicators of the

some college while 43% had earned a college diploma. There perceived change in home value. Thus, across all seven states,

were similar parallels in household size and income. Statisti- the experimental stimuli yielded a similar range of respon-

cal tests between the two samples were not possible without dent answers.

the standard deviation in the National Gardening sample, but

many similarities were evident among them. Relative importance of attributes. For each of the seven

states, relative importance of factors increased from plant

Time and money expenditures on lawn and garden. The material type to plant size to design sophistication (Table 2).

mean number of hours respondents stated they spent on their Design sophistication was the most important landscape fac-

lawn and yard during a typical summer week in 1998 ranged tor in these seven states, accounting for 40 to 45% of the

from 3.9 hours in Delaware to 9.8 hours in Mississippi (Table value added to the home. Paired sample t-tests indicated that

1). In several individual cases in each state, respondents stated for each state, there was one significant difference between

that they work over 30 hours per week on their lawn and the relative importance of the three factors in each location.

garden. With these extremes, the median hours per week was Louisiana respondents valued sophistication less than North

Table 2. Relative importance percentages of three landscape attributes for participants from seven states and the average percent increase over base

home value for the highest level of each factor in the landscape design.

Plant Plant Design Average percent increase

State material size sophistication over base home value

Delaware 24.8 30.6 44.6 6.79%

Kentucky 20.8 36.4 42.8 8.74%

Louisiana 23.4 32.9 43.7 5.54%

Mississippi 23.9 34.1 42.0 10.76%

North Carolina 24.4 34.5 41.2 7.06%

South Carolina 23.3 34.1 42.6 11.36%

Texas 21.0 39.0 40.1 10.16%

Average (mean) 22.4 35.9 41.7 9.0%

130 J. Environ. Hort. 23(3):127–133. September 2005

Table 3. Utility score and percentage change over base home values for three levels of landscape plant size, design sophistication, and four levels of

diversity of landscape material in seven locations.

Delaware Kentucky Louisiana Mississippi North Carolina South Carolina Texas

Utility % Utility % Utility % Utility % Utility % Utility % Utility %

Base home value $180,000 $140,000 $176,000 $150,000 $220,000 $150,000 $125,000

Plant sizez

Small –1971.7 –1.1 –2210.2 –1.6 –2094.8 –1.2 –2738.4 –1.8 –2698.6 –1.2 –2785.9 –1.9 –2442.6 –2.0

Medium 68.3 0.0 26.5 0.0 1097.9 0.6 –530.4 –0.4 –433.5 –0.2 –187.0 –0.1 615.2 0.5

Large 1903.4 1.1 2183.8 1.6 996.9 0.6 3268.8 2.2 3132.1 1.4 2973.0 2.0 1827.4 1.5

Design sophisticationy

Foundation –2792.1 –1.6 –2732.3 –2.0 –1561.3 –0.9 –3872.1 –2.6 –3655.5 –1.7 –3901.0 –2.6 –4105.0 –3.3

Island –57.6 –0.0 295.7 0.2 98.2 0.1 345.4 0.2 348.0 0.2 598.3 0.4 856.5 0.7

Sophisticated 2849.7 1.6 2436.6 1.7 1463.0 0.8 3526.7 2.4 3307.5 1.5 3302.8 2.2 3248.6 2.6

Diversity of landscape materialx

Evergreen –1199.1 –0.7 –1101.6 –0.8 –1340.5 –0.8 –1752.7 –1.2 –1663.4 –0.8 –1371.6 –0.9 –229.8 –0.2

+ Deciduous –850.3 –0.5 –722.6 –0.5 –1186.8 –0.7 –1449.6 –1.0 –1421.0 –0.7 –1562.3 –1.0 –2171.7 –1.7

+ 20% Color 115.8 0.1 414.5 0.3 1666.1 1.0 728.4 0.5 728.4 0.3 555.1 0.4 1816.3 1.5

+ Hardscape 1933.6 1.1 1409.6 1.0 861.1 0.1 2473.9 1.7 2473.9 1.1 2378.8 1.6 585.3 0.5

z

Plant size was defined as: (1) small = smallest plant size commercially available for the product, (2) medium = intermediate plant size between small and large

which was commercially available and (3) large = largest plant size commercially available.

y

Design sophistication was defined as (1) Foundation = foundation planting only, (2) Island = foundation planting with one large, oblong island planting and one

or two single specimen or shade trees in the lawn and (3) Sophisticated = a foundation planting with adjoining beds and two or three large island plantings, all

incorporating curved bedlines.

x

The plant material types were defined as : (1) Evergreen = evergreen only, (2) + Deciduous = evergreen and deciduous plants, (3) + 20% Color = evergreen and

deciduous plants with 20% of the visual area of the landscape beds planted in annual or perennial color, and (4) + Hardscape = evergreen and deciduous plants,

20% annual or perennial color, and the addition of a colored brick sidewalk entrance.

Carolina (p = 0.003). There were no significant differences the smallest plants were used, perceived home values de-

between any other pairs of states for design sophistication. creased by 2.3%. When the largest plant sizes were used,

Relative importance of plant size was of intermediate im- perceived home value increased by 2.8%. Louisiana showed

portance between design sophistication and plant material, the smallest difference in perceived home value due to plant

and ranged from 39% in Texas to 30.6% in the Delaware size. The estimated home value for Louisiana was $176,000.

sample. In paired t-tests, North Carolina, South Carolina, and When small plants were used, perceived home value de-

Mississippi were similar (NC to SC p = 0. 191; NC to MS creased 1.2%, while the use of the largest plant sizes increased

p = 0. 523; MS to SC p = 0.455) with res pect to the relative values by 0.6%. In northern climates, plant size will increase

importance of plant size. Additionally, Louisiana was simi- at a slower rate than in more southern climates.

lar to Mississippi (p = 0.184) and North Carolina (p = 0.567). For respondents across all states, the simplest design (foun-

Texas was similar to Kentucky (p = 0.188). Kentucky was dation-only plantings) decreased perceived home value by

similar to South Carolina (p = 0.134). Generally, plant size an average of 2.1%, while the most sophisticated landscape

importance appeared to decrease as plant growing zone num- design increased home values by an average of 1.9% (Table

ber increased. 3). Island plantings added to foundation-only beds had virtu-

For respondents from all states, the diversity of plant ma- ally no effect on perceived home value. Texas showed the

terial type installed contributed the least to the value added greatest range in perceived home value due to design sophis-

to the home landscape. In all states, plant material type con- tication. The estimated base home value for Texas was

tributed 16 to 22% less to the added home value than did $125,000. Foundation-only plantings decreased perceived

design sophistication. The relative importance of plant ma- home value by 3.3%, while sophisticated designs increased

terial in Delaware and North Carolina was similar. Louisi- perceived home values by 2.6%. Louisiana had the smallest

ana was different than North Carolina (p = 0.042). The re- variation between foundation and sophisticated plantings.

maining comparisons of Delaware and Louisiana to any other Foundation plantings decreased home values by 0.9%, while

states showed significant differences (p < 0. 01). Generally, sophisticated plantings increased home values by 0.8%.

plant material type was perceived as having half the impor- Generally, the additional diversity of plant material in-

tance of design sophistication and less important than plant creased perceived home value (Table 3). Data from respon-

size. dents across all states found that material levels 1 and 2 de-

creased home values, while material level 3 increased per-

Changes in perceived home value. Across all states, smaller ceived home values somewhat. The use of materials described

plant sizes reduced perceived home values (as indicated by in level 4 increased perceived home values most. Missis-

utility scores), while larger plant sizes increased perceived sippi, with a base home value of $150,000, showed the larg-

home values (Table 3). The medium-sized plants produced est fluctuation between material levels 1 and 2 when com-

virtually no change to existing home values. The greatest pared to designs containing all four material levels. Material

increase in perceived value due to plant size was seen in North levels 1 and 2 decreased home values by 1.0%, while levels

Carolina, where the base home value was $220,000. When 3 and 4 increased perceived home values by 1.7%. Louisi-

J. Environ. Hort. 23(3):127–133. September 2005 131

ana showed the smallest variation in perceived home value; Results of this study indicate that a ‘good’ landscape adds,

material levels 1 and 2 decreased home value by 0.7%, while depending on region of the country, anywhere from 6 to 11%

the addition of all four levels increased perceived home value to the base value of the home. The landscape attributes that

by 0.1%. For Louisiana and Texas, the addition of material contributed most to the increase in perceived home value

levels 3 and 4 to existing levels 1 and 2 increased perceived were, in order, design sophistication, plant size, and plant

value by 1.0 and 1.5% respectively. In these locations, the material type. Clearly, the investment in a good landscape

addition of material level 4 decreased home values in com- can be recovered and increase the perceived value of a home.

parison to the landscape containing only material levels 1, 2 The minimalist landscapes, with small plant size and little

and 3. However, the addition of material level 4 to existing sophistication, even detracted from the perceived value of

material levels 1–3 in the remaining states (DE, KY, MS, the home. The landscape company manager now has con-

NC and SC) increased base home values by an average of crete data to show that a good landscape adds to the value of

1.2%. a home, and is a home improvement that will increase per-

ceived home value and, unlike most home improvements,

Overall preference. All states shared the same most pre- appreciate over time.

ferred landscape: a sophisticated design incorporating large

deciduous, evergreen, and annual color plants and colored Literature Cited

hardscape. The percent increase in home value from the least

valued to the most valued varied among states from 5.5% in 1. Adobe Systems, Inc. Adobe PhotoShop version 5.0. Adobe Systems,

South Carolina to 11.4% in Mississippi (Table 2). In all states, Inc. San Jose, CA.

the ranking from least percentage added to most percentage 2. American Nursery and Landscape Association. 2002. Understanding

added followed the same pattern for percent increase from the Landscape Consumer. American Nursery and Landscape Association.

Washington, DC.

the least favored to most favored, percent increase of the most

favored over the predicted base and percent decrease of the 3. Anonymous. 1986. The Value of Landscaping. Weyerhaeuser Nursery

Products Division. Tacoma, WA.

least favored over the predicted base. Additionally, the order

of the state rankings of the percent increase from the least 4. Barton, S., J. Brooker, C. Hall, and S. Turner. 1999. Review of

customer preference research in the nursery and landscape industry. J.

favored to the most favored bore no resemblance to the rank Environ. Hort. 16:118–124.

order of the base price of the house. In other words, large

5. Behe, Bridget K., Elizabeth C. Moore, Arthur C. Cameron, and Forest

percent increases in home value were not associated with S. Carter. 2003. Consumer perceptions for and uses and perceptions of

larger base prices. selected flowering perennial plants. HortScience 38:460–464.

Why were these results somewhat different than Hardy 6. Behe, B., R. Nelson, S. Barton, C. Hall, C. Safley, and S. Turner.

(13) found, using identical methodology? The first differ- 1999. Consumer preferences for geranium flower color, leaf variegation and

ence was the venue. Michigan participants were the oldest price. HortScience 34:740–742.

and had the highest income when compared to other respon- 7. Bretton-Clark. 1992. Conjoint Designer version 3. Bretton-Clark,

dents. Yet they were not dissimilar in age and income to par- Morristown, NJ.

ticipants in all states (data not shown). Michigan respondents 8. Bush, A.J. and A. Parasuraman. 1985. Mall intercept versus telephone-

were similar to respondents from other states in terms of interviewing environment. J. Advertising Res. 25:36–44.

number of persons in the household, and hours and dollars 9. Butterfield, B.W. 2004. National Gardening Survey 2003. The

spent in the garden. Michigan respondents did place a higher National Gardening Association, Inc. Burlington, VT.

relative value on plant size than respondents from all other 10. Census of Retail Trade, 1997. http://www.census.gov/epcd/www/

markets. A flower show venue was used to collect data in econ97.html accessed April 18, 2005.

Michigan, not a home and garden show. Participants to the 11. Churchill, G.A. and D. Iacobucci. 2005. Marketing Research:

former venue may have added even more value for having a Methodological Foundations. Ninth Edition. South-Western, Mason, OH.

colorful landscape than the participants from other venues. 12. Cory, J. 2003. 2002 Cost vs. Value Report. Remodeling Online.

The second reason for some discrepancy may be USDA har- Accessed September 23, 2003. http://remodelingonline.yellowbrix.com/

diness zone. The authors speculate that perhaps in colder pages/remodelingonline/Story.nsp?story_id=1000027497.

hardiness zones, where plants grow more slowly, gardeners 13. DeBossu, A. 1988. What do people want to buy? Amer. Nurseryman.

value plant size more and perceive that more colorful plants May 1, 1988. 91–96.

add greater value. Respondents from warmer hardiness zones, 14. Denstadli, J.M. 2000. Analyzing Air Travel: A Comparison of different

where plant material has a longer growing season and grows survey methods and data collection procedures. J. Travel Res. 39:4–11.

more quickly, may value landscape design sophistication 15. Frank, C., E. Simonne, B. Behe, and A. Simonne. July 2001.

more than plant size. Design sophistication was the second Consumer preferences for color, price, and Vitamin C content of bell peppers.

most important attribute to Michigan participants. Respon- HortScience 36:795–800.

dents from all venues agreed that plant material used in the 16. Gaasbeck, A. and V. Bouwman. 1991. Conjoint analysis in market

landscape was relatively the least important factor. research for horticultural products. Acta Hort.: Hort. Economics and Mktg.

295:121–125.

We found that in all markets, consumers preferred the larg-

est, most sophisticated, and colorful landscape design. The 17. Gineo, M. 1988. Nursery marketing can be improved. J. Environ Hort.

6:72–75.

sophisticated planting category consisting of a foundation

planting with adjoining beds and two or three large island 18. Hardy, J., B. Behe, S. Barton, T. Page, R. Schutzki, K. Muzii, R.T.

Fernandez, M.T. Haque, J. Brooker, C. Hall, R. Hinson, P. Knight, R. McNiel,

plantings, all incorporating curved bedlines, increased home D.B. Rowe, and C. Safley. 2000. Consumers preferences for plant size, type

values by an average of 1.8%. This indicates that consumers of plant material and design sophistication in residential landscaping. J.

in the states tested could increase home values by $2,375– Environ. Hort. 18:224–230.

$3,648 depending upon the initial base home value and cost 19. Hartigan, J.A. 1975. Clustering Algorithms. John Wiley and Sons.

of materials and installation of the plants. New York, NY.

132 J. Environ. Hort. 23(3):127–133. September 2005

20. Henry, M. 1999. Landscape quality and the price of single family 27. Lysaker, R.L. 1989. Data collection methods in the U.S. J. Market

houses: further evidence from home sales in Greenville, South Carolina. J. Research Soc. 31:477–489.

Environ. Hort. 17:25–30.

28. Morales, D. 1980. The contribution of trees to residential property

21. Henry, M. 1994. The contribution of landscaping to the price of single value. J. Arboriculture 6:305–308.

family homes: A study of home sales in Greenville, South Carolina. J.

Environ. Hort. 12:65–70. 29. Nasar, J. 1983. Adult viewers’ preference in residential scenes: a study

of the relationship of environmental attributes to preference. Environ. and

22. Kalmbach, K. and J. Kielbaso. 1979. Resident attitudes toward Behavior 15:589–614.

selected characteristics of street tree plantings. J. Arboriculture 5:124–129.

30. Oppenheim, P. 2000. Segmentation and target marketing in a floral

23. Kelley, Kathleen M., Bridget K. Behe, John A. Biernbaum, and market. Acta Hort. (ISHS) 536:529–536.

Kenneth L. Poff. 2002. Combinations of colors and species of containerized

edible flowers: Effect on consumer preferences. HortScience 37:218–221. 31. Orland, B., J. Vinning, and A. Ebreo. 1992. The effect of shade trees

on perceived value of residential property. Environ. and Behavior 24:298–

24. Kelley, Kathleen M., Bridget K. Behe, John A. Biernbaum, and 325.

Kenneth L. Poff. 2001. Consumer preference for edible flower color,

container size, and price. HortScience 36:801–804. 32. Sommer, R. 1997. Further cross-national studies of tree form

preference. Ecological Psychology 9:153–160.

25. Khatamian, H. and A. Stevens. 1994. Consumer marketing preferences

for nursery stock. J. Environ. Hort. 12:47–50. 33. Spooner, C. and B. Flaherty. 1993. Comparison of three data collection

methodologies for the study of young illicit drug users. Australian J. of Public

26. Klingeman, W.E., D.B. Eastwood, J.R. Brooker, C.R. Hall, B.K. Behe,

Health 17:195–203.

and P.R. Knight. 2004. Consumer survey identifies plant management

awareness and added value of dogwood powdery mildew resistance. 34. SPSS Inc. 1998. SPSS Base 8.0 for Windows user’s guide. SPSS Inc.

HortTechnology 14:275–282. Chicago, IL. SPSS Inc. 1997. SPSS Conjoint 8.0. SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL.

J. Environ. Hort. 23(3):127–133. September 2005 133

View publication stats

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Tle Agri Grade 6 Module 3Document9 paginiTle Agri Grade 6 Module 3Maribel A. Bustillo100% (5)

- Landscape ArchitectureDocument12 paginiLandscape ArchitectureArh Eman84% (19)

- CV Nov 2023 UpdatedDocument6 paginiCV Nov 2023 Updatedapi-540640398Încă nu există evaluări

- Trees - Built Environment - Economics.WolfDocument41 paginiTrees - Built Environment - Economics.WolfRamesh RavulaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Therapeutic Garden Desing - ASLA Spring 2006Document8 paginiTherapeutic Garden Desing - ASLA Spring 2006Konstantinidis851Încă nu există evaluări

- A Roadmap to Green Supply Chains: Using Supply Chain Archaeology and Big Data AnalyticsDe la EverandA Roadmap to Green Supply Chains: Using Supply Chain Archaeology and Big Data AnalyticsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strategic Green Infrastructure Planning: A Multi-Scale ApproachDe la EverandStrategic Green Infrastructure Planning: A Multi-Scale ApproachÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biodiversity Planning and Design: Sustainable PracticesDe la EverandBiodiversity Planning and Design: Sustainable PracticesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advancing Sustainable Bioenergy: Evolving Stakeholder Interests and The Relevance of ResearchDocument15 paginiAdvancing Sustainable Bioenergy: Evolving Stakeholder Interests and The Relevance of ResearchrosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final PaperDocument9 paginiFinal Paperapi-538876686Încă nu există evaluări

- JJRC 1029 Edit Report - PDF Proofs JRS ParsaLordPutrevuandKreeger Aug2014Document19 paginiJJRC 1029 Edit Report - PDF Proofs JRS ParsaLordPutrevuandKreeger Aug2014Jess RoldanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2005 Jacobs EnvironmentDocument17 pagini2005 Jacobs EnvironmentcardozorhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quantitative Mineral Resource Assessments - An Integrated Approach - Donald Singer, W. David MenzieDocument232 paginiQuantitative Mineral Resource Assessments - An Integrated Approach - Donald Singer, W. David MenzieparagjduttaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MC Kinley 2017 Biol ConsDocument15 paginiMC Kinley 2017 Biol ConsAfuye MiracleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Krystal Drysdale CVDocument3 paginiKrystal Drysdale CVapi-203510663Încă nu există evaluări

- Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews: SciencedirectDocument10 paginiRenewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews: SciencedirectCarolina MacielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews: SciencedirectDocument10 paginiRenewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews: SciencedirectCarolina MacielÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sustainable Sites Handbook: A Complete Guide to the Principles, Strategies, and Best Practices for Sustainable LandscapesDe la EverandThe Sustainable Sites Handbook: A Complete Guide to the Principles, Strategies, and Best Practices for Sustainable LandscapesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lower Midwest: Ree GuideDocument127 paginiLower Midwest: Ree GuidealexÎncă nu există evaluări

- Greening America's Schools: Costs and BenefitsDocument26 paginiGreening America's Schools: Costs and BenefitsKristian Erick BautistaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CV Dennhardt 2019Document14 paginiCV Dennhardt 2019api-291725871Încă nu există evaluări

- The Greening of Industrial Ecosystems (1994) : This PDF Is Available atDocument270 paginiThe Greening of Industrial Ecosystems (1994) : This PDF Is Available atBALAGANESH PÎncă nu există evaluări

- Green BuyingDocument3 paginiGreen BuyingninhxuanhaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oliver EMS 2012famer Engagement SSDDocument11 paginiOliver EMS 2012famer Engagement SSDCindy Quispe AndradeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eficiencia 1Document136 paginiEficiencia 1Darwin AuquiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Predictict Green Product ConsumptionDocument13 paginiPredictict Green Product ConsumptionKetut SutapaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper On Community GardensDocument7 paginiResearch Paper On Community Gardensafedsxmai100% (1)

- Socioeconomic Survey of Nursery AutomationDocument2 paginiSocioeconomic Survey of Nursery AutomationubaidÎncă nu există evaluări

- 8.alineacion Del Tamaño de Incentivo Con El Desempeño Responsable de La Organizacion de AtencionDocument187 pagini8.alineacion Del Tamaño de Incentivo Con El Desempeño Responsable de La Organizacion de AtencionAnonymous ydO9B4J2Încă nu există evaluări

- Ecological Principles of Landscape Management: Soils and the Processes That Determine Success of Landscape Designs, Farms and PlantsDe la EverandEcological Principles of Landscape Management: Soils and the Processes That Determine Success of Landscape Designs, Farms and PlantsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal Pone 0266475Document22 paginiJournal Pone 0266475Emmanuel Mary Angelo ChuaÎncă nu există evaluări

- XXXX Important Adopting Proactive Environmental Strategy The Influence of Stakeholders and Firm Size Environmental Strategy, Stakeholders, and SizeDocument24 paginiXXXX Important Adopting Proactive Environmental Strategy The Influence of Stakeholders and Firm Size Environmental Strategy, Stakeholders, and SizeJhony JoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Willingnessto Purchase Greenproducts Evidencefrom Educated Segmentof Southern PunjabDocument9 paginiWillingnessto Purchase Greenproducts Evidencefrom Educated Segmentof Southern PunjabKylee NathanielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper On Natural Resource ManagementDocument7 paginiResearch Paper On Natural Resource Managementfvf66j19100% (1)

- KithengardeningpaperDocument9 paginiKithengardeningpaperbababassimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Building Green For The Future PDFDocument108 paginiBuilding Green For The Future PDFangga ferdianÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S1550742422000884 MainDocument10 pagini1 s2.0 S1550742422000884 MainTsega BelayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Green Jobs Research PaperDocument8 paginiGreen Jobs Research Paperogisxnbnd100% (1)

- Profitable Farms and Woodlands - A Practical Guide in Agroforestry For Landowners, Farmers and RanchersDocument108 paginiProfitable Farms and Woodlands - A Practical Guide in Agroforestry For Landowners, Farmers and RanchersTimothy MoralesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wind Energy For Power Generation: K.R. RaoDocument1.480 paginiWind Energy For Power Generation: K.R. RaoVetrivel PerumalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sustainable DesignDocument325 paginiSustainable DesignJett Soriano100% (1)

- Writing A Research Paper On AgricultureDocument6 paginiWriting A Research Paper On Agriculturegw1sj1yb100% (1)

- Healing Gardens in Children's Hospitals - Reflections OnDocument19 paginiHealing Gardens in Children's Hospitals - Reflections Onmiščafl (Miro)Încă nu există evaluări

- OUTPUT - Environmental Project Proposal - BaysaJoshuaDocument5 paginiOUTPUT - Environmental Project Proposal - BaysaJoshuaJOSHUA BAYSAÎncă nu există evaluări

- MLA Students Redesign Beaumont Public Housing Site: Junior LAUP Faculty Visit Federal Funding AgenciesDocument7 paginiMLA Students Redesign Beaumont Public Housing Site: Junior LAUP Faculty Visit Federal Funding AgenciesLarry SheltonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Environmentally Responsible Design: Green and Sustainable Design for Interior DesignersDe la EverandEnvironmentally Responsible Design: Green and Sustainable Design for Interior DesignersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rests UstDocument10 paginiRests UstchristinekehyengÎncă nu există evaluări

- Environmental Management Strategies in Agriculture: Agriculture and Human Values September 2011Document7 paginiEnvironmental Management Strategies in Agriculture: Agriculture and Human Values September 2011Ferly OktriyediÎncă nu există evaluări

- TheRoleofGovernmentNurseriesinLeyte 13mayDocument18 paginiTheRoleofGovernmentNurseriesinLeyte 13maysolisirahjoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quantitative Biology For The 21st CenturyDocument49 paginiQuantitative Biology For The 21st CenturyAndré BarrosÎncă nu există evaluări

- PreviewpdfDocument25 paginiPreviewpdfaugustoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Perception of The Importance of Chemistry Research Papers and Comparison To Citation RatesDocument14 paginiPerception of The Importance of Chemistry Research Papers and Comparison To Citation RatesGabriel LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Profitable Farms and Woodlands: A Practical Guide in Agroforestry For Landowners, Farmers and RanchersDocument108 paginiProfitable Farms and Woodlands: A Practical Guide in Agroforestry For Landowners, Farmers and Rancherspwilkers36100% (2)

- Methods For Rapid Testing of Plant and Soil Nutrients: July 2017Document42 paginiMethods For Rapid Testing of Plant and Soil Nutrients: July 2017Herik SugeruÎncă nu există evaluări

- People-Plant Council Newsletter - Fall - Winter 1996Document8 paginiPeople-Plant Council Newsletter - Fall - Winter 1996Garden Therapy NewslettersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sustainable Land DevelopmentDocument59 paginiSustainable Land DevelopmentMervin Jake MacayanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Resume Samantha WordenDocument3 paginiResume Samantha Wordenapi-283456631Încă nu există evaluări

- Green Luxury: A Case Study of Two Green HotelsDocument31 paginiGreen Luxury: A Case Study of Two Green HotelsVynn CalcesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sustainable DesignDocument325 paginiSustainable DesignRavnish Batth100% (5)

- Sustainable Design - Ecology, Architecture and PlanningDocument325 paginiSustainable Design - Ecology, Architecture and PlanningMelid TrtovacÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bus Terminal Design GuidelinesDocument225 paginiBus Terminal Design GuidelinesReu George71% (7)

- 2 PDFDocument1 pagină2 PDFpalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Landscape 160216192355Document29 paginiLandscape 160216192355palaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Casestudymethod PDFDocument58 paginiCasestudymethod PDFpalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 PDFDocument1 pagină1 PDFpalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 PDFDocument1 pagină4 PDFpalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 13 - Chapter 3Document47 pagini13 - Chapter 3palaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 PDFDocument1 pagină3 PDFpalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrated Bus Terminus CumDocument5 paginiIntegrated Bus Terminus CumpalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2Document12 pagini2palaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 8 PuducherryDocument4 pagini8 PuducherrypalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- M-Arch Thesis Program Report-2020-FinalDocument31 paginiM-Arch Thesis Program Report-2020-FinalpalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2.value of Urban Open Space PDFDocument8 pagini2.value of Urban Open Space PDFpalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11 Balogh PDFDocument12 pagini11 Balogh PDFpalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vishakapatnam S CPDocument92 paginiVishakapatnam S CPgokedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 2Document35 paginiChapter 2palaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presentation 1Document1 paginăPresentation 1palaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11 Balogh PDFDocument12 pagini11 Balogh PDFpalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2.value of Urban Open Space PDFDocument8 pagini2.value of Urban Open Space PDFpalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2Document12 pagini2palaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4h floriLG PDFDocument61 pagini4h floriLG PDFpalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4h floriLG PDFDocument61 pagini4h floriLG PDFpalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bibliography: - Site Analysis / Edward T. WhiteDocument45 paginiBibliography: - Site Analysis / Edward T. WhitepalaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Floriculture Hand BookDocument6 paginiFloriculture Hand BookSantanu AcharyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indo Islamic CultureDocument8 paginiIndo Islamic CultureM Teja64% (11)

- 2 OrnamentalDocument168 pagini2 Ornamentalনাজমুল হক শাহিনÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic Principles of Landscape DesignDocument12 paginiBasic Principles of Landscape DesignAman KashyapÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ornamental Horticulture: Google Search Anilrana13014Document168 paginiOrnamental Horticulture: Google Search Anilrana13014palaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artpersentation 150808180634 Lva1 App6892Document72 paginiArtpersentation 150808180634 Lva1 App6892Megha PanchariyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Historyislamicarchitecture 110915110615 Phpapp01Document30 paginiHistoryislamicarchitecture 110915110615 Phpapp01nlalamÎncă nu există evaluări

- PetuniasDocument3 paginiPetuniasCharles StathamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study On Swarnjayanti ParkDocument21 paginiCase Study On Swarnjayanti ParkNitin Shivhare100% (1)

- Genius Loci Towards ADocument90 paginiGenius Loci Towards AAndreeaDitu100% (1)

- Importance of Vegetable Farming: Important Place in Agricultural Development and Economy of The CountryDocument18 paginiImportance of Vegetable Farming: Important Place in Agricultural Development and Economy of The CountryKareen Carlos GerminianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Excerpt From "The Shepherd's Life" by James Rebanks.Document9 paginiExcerpt From "The Shepherd's Life" by James Rebanks.OnPointRadioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soils of India - Classification and Characteristics - Clear IAS PDFDocument6 paginiSoils of India - Classification and Characteristics - Clear IAS PDFRavi BanothÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mulching: E. Mulch ApplicationDocument2 paginiMulching: E. Mulch ApplicationDenz MercadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Geotechnical Investigation For The Proposed New Buildings at I.I.R.S. Dehradun, UttaranchalDocument26 paginiGeotechnical Investigation For The Proposed New Buildings at I.I.R.S. Dehradun, UttaranchalganeshkumarkotaÎncă nu există evaluări

- On GloriosaDocument14 paginiOn GloriosaManish Patel0% (1)

- Geography India Drainage SystemDocument6 paginiGeography India Drainage SystempratÎncă nu există evaluări

- CBLM in Horticulre NC II Uc 2 VegetablesDocument17 paginiCBLM in Horticulre NC II Uc 2 Vegetablesvincelda67% (6)

- Square Foot GardeningDocument2 paginiSquare Foot GardeningRichard Davies100% (1)

- Desert Ecosystem IndiaDocument16 paginiDesert Ecosystem IndiaIndie AcresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tree Planting GuideDocument16 paginiTree Planting GuideJexÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guide To Growing Strawberries in ContainersDocument8 paginiGuide To Growing Strawberries in ContainersDrought Gardening - Wicking Garden Beds100% (1)

- Assignment in Geomorphology PDFDocument22 paginiAssignment in Geomorphology PDFAngelicaOlaesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 09 Social Science Key Notes Geo Ch2 Physical Features of IndiaDocument4 pagini09 Social Science Key Notes Geo Ch2 Physical Features of IndiaHimanshu JoshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.C.S Moisture ContentDocument18 paginiG.C.S Moisture ContentDaniel KariukiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maryland Native Plants For Rain Gardens - RainScaping CampaignDocument6 paginiMaryland Native Plants For Rain Gardens - RainScaping CampaignFree Rain Garden Manuals and More100% (1)

- AQUATICS Keeping Ponds and Aquaria Without Harmful Invasive PlantsDocument9 paginiAQUATICS Keeping Ponds and Aquaria Without Harmful Invasive PlantsJoelle GerardÎncă nu există evaluări

- Geotechnical Investigation ReportDocument40 paginiGeotechnical Investigation ReportJoseph Marriott AndersonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effect of Integrated Nutrient Management On Plant Growth, Flower Yield and Quality of Dahlia (Dahlia Variabilis) C.V "Kenya White.Document39 paginiEffect of Integrated Nutrient Management On Plant Growth, Flower Yield and Quality of Dahlia (Dahlia Variabilis) C.V "Kenya White.ChandanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hydroponics and AeroponicsDocument12 paginiHydroponics and AeroponicsAyan ChakrabortyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Soil Erosion and Soil ConservationDocument7 paginiSoil Erosion and Soil ConservationsvschauhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Constructed Wetland Design ManualDocument181 paginiConstructed Wetland Design ManualVishal Duggal100% (1)

- Notes of CH 2 Physical Features of India - Class 9th Geography Study Rankers PDFDocument10 paginiNotes of CH 2 Physical Features of India - Class 9th Geography Study Rankers PDFvivek pareek100% (1)

- Worksheet 2 10-04-2020 Class - VII Social Studies Lesson: The Desert I. Fill in The BlanksDocument2 paginiWorksheet 2 10-04-2020 Class - VII Social Studies Lesson: The Desert I. Fill in The Blanksvijay pal shivranÎncă nu există evaluări