Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Fil 14 p.37 Poem

Încărcat de

Tommy Chen0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

453 vizualizări4 paginiThis document provides an analysis of an anonymous 17th century Tagalog poem titled "May Bagyo Mm't May Rilim" (Though It Is Stormy and Dark). The poem is considered an early example of written poetry by a native Tagalog poet. It contains rich imagery and metaphor to describe a child's struggle against temptation and search for God during a storm. While drawing on folk poetry traditions, the poem's unified structure across five stanzas marks a transition to written poetic forms. The analysis examines the poem's complex language, themes of courage and faith, and significance as one of the earliest known works of Tagalog literature.

Descriere originală:

filipino poem

Titlu original

Fil-14-p.37-Poem

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentThis document provides an analysis of an anonymous 17th century Tagalog poem titled "May Bagyo Mm't May Rilim" (Though It Is Stormy and Dark). The poem is considered an early example of written poetry by a native Tagalog poet. It contains rich imagery and metaphor to describe a child's struggle against temptation and search for God during a storm. While drawing on folk poetry traditions, the poem's unified structure across five stanzas marks a transition to written poetic forms. The analysis examines the poem's complex language, themes of courage and faith, and significance as one of the earliest known works of Tagalog literature.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

453 vizualizări4 paginiFil 14 p.37 Poem

Încărcat de

Tommy ChenThis document provides an analysis of an anonymous 17th century Tagalog poem titled "May Bagyo Mm't May Rilim" (Though It Is Stormy and Dark). The poem is considered an early example of written poetry by a native Tagalog poet. It contains rich imagery and metaphor to describe a child's struggle against temptation and search for God during a storm. While drawing on folk poetry traditions, the poem's unified structure across five stanzas marks a transition to written poetic forms. The analysis examines the poem's complex language, themes of courage and faith, and significance as one of the earliest known works of Tagalog literature.

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 4

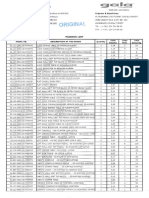

LUMBERA: TAGALOG POETRY 121

The Tagalog Poets. The first example of written poetry by

a native Tagalog poet is "May Bagyo Mm't May Rilim"

(Though It Is Stormy and Dark), an anonymous poem which

appeared, with San Jose's auit and Bagongbanta's romance,

in Memorid de la vida. San J& simply identifies the poet

as "una tcrgwJu persona," an unfortunate omission because the

poem is a fine specimen of early Tagalog poetry for which

the author richly deserves to be celebrated. The poem has

remained buried for more than three centuries and a half

since its publication, unnoticed by scholars who honored Ba-

gongbanta with their comment. Like Bagongbanta's poem, it

deals with the merits of San J&'s book, using imagery that

se em either to have been borrowed from Bagongbanta or to

have inspired that of the Zudino poet.

"hlay Bagyo" is a carefully crafted poem that transcends

its prosaic subject matter and becomes, through the use of

evocative imagery, a touching affirmation of Christian heroism.

The opening stanza announces the motif of struggle which

will appear in the remaining four stanzas:

May bagyo ma,t, may rilim

ang ola,y, titiguisin,

a&,y, magpipilit din:

aquing paglalacbayin

toloyin cong hanapin

Dios na ama r1amin.4~

It is nighttime and a storm is raging, and the speaker sees

himself as a child who refuses to give himself up to wailing

in spite of his fears." He decides to set out in search for his

father who is God. This is courage, and it will sustain the

speaker in the struggle described in the succeeding stanzas.

ble the Spaniards. Therefore, is there not every reason to want b ac-

quire this other trait, that of being able to speak their language?

*6Though it is stormy and dark, / I'll strain my tearful plainte /

and Btruggle on- / I'll set out on a voyage / and persist in my search /

for Gad our Father.

+e An ambiguity is created in the second line by the phrase olu,y.

which may be either olan ay (rain + linking particle) or ola ay (bawl-

ing of a child $- linking particle.)

I22 PHILIPPINE STUDIES

Temptation appears as an insidious force in the next

stanza. Its action is ambiguously expressed in the word ma-

baomabaoin, which may either mean that temptation is a

weight that bears down on its victim (in later religious poetry,

the word is used when Christ takes up His cross), or that

it is a lover-seducer mounting his victim for the love act.47

Cun di man magupiling

taceong mabaomabaoin,

aco,y, mangangahas din:

itong libro,y, basahin.

at dito co hahangoin

aquing sasandatahin.48

But the speaker is confident, and he reveals the reason be-

hind his courage: the book (Memorial de la uida) gives power

with which to overcome temptation.

That power consists in the light of God which the author

has allowed to shine through. That light has given back

sight to the speaker. The third stanza is thus the pivohal

section where the child in the first stanza encounters the

father he has set out to find:

Cun dati mang nabulag

aco,y, pasasalamat,

na ito ang liuanag

Dios ang nagpahayag

sa Padreng nagsiualat

nitong mabuting s ~ l a t . ~ ~

The speaker is reunited with his father, God, and so has

emerged from the storm and daqkness. In the stanza below,

he speaks of a tempest a t sea which capsizes his boat. But

he does not despair:

. ---- - --

4"~bao, the root-word in mabaomabaoin, is used with sexual con-

notations in the confeswnurio of San J& which is in Pinpin's Librong

PagaaraEan. See Artigas, p. 219.

'SThough it doesn't sleep a wink, / this temptation that bears

down on me, / still will I dare / to read this book, / and from it,

draw / the weapon I'll wield.

'9 Though blinded in the past, / I'll give thanks / for this light /

which God let shine / upon the priest who has made known / this

noble book.

LUMBERA: TAGALOG POETRY

Nagiua ma$, nabagbag

daloyong matataas,

acoy magsusumicad

babagohin ang lacas:

dito rin hahaguilap

timbulang icaliligta~.~O

And defeated as he might be by the misforturns that come

upon him, he cannot be completely helpless. The final stanza

affirms the strength that God's light gives:

Cun lompo ma,t, cun pilay

anong di icahacbang

naito ang aacay

magtuturo nang daan:

toncod ay inilaan

sucat pagcatibayan.51

The poem has very definite affinities with folk poetry.

The meter is heptasyllabic and each stanza is self-contained.

But what makes it readily identifiable as a poem created

in the tradition of folk podtry is its use of the talinghaga.

This sets it apart from the verses of ithe missionary poets

who were wary of metaphors. It is also the remon for the

richness of meaning which makes the five-stanza poea in-

finitely more complex than all the poems of the missionary

poets put together.

On the other hand, "May Bagyo" is quite unlike folk

poetry. Its stanza form is something that was never to be

repeated in any of the poems of the entire period of the

Spanish Occupation. This might be taken as an indication

that the poem was written, not composed orally. Only

one putting lines together for purposes of publication would

find any reason for breaking away from the conventional

forms of the oral tradition. Another indication that "May

Ragyo" is written poetry is its use of language. The am-

biguities of the language may be due to the d i a n c e betwen

50 Though tossed and dashed / by huge waves, / I'll thrash my

legs / and renew my strength- / in this [book] will I grasp / for the

buoy that saves.

5 1 Though disabled and limping, / nothing can hold back my steps,

/ for this [book] will take me by the hand / and show me the way- /

the staff has becn prepared / to give me strength.

124 PHILIPPINE STUDIES

what Tagalog was in the seventeenth century and what it

is now. Nevertheless, one notes a penchant for subtleties in

the poet's choice of words, which prefers the double-edged

word consistently. For instance, the use of nagsiualat takes

advantage of the double meaning arising from the existence

of two r o d s to which the verb may be related: simlat, meaning

"reveal," and ualat, meaning "scatter." The literal sense of

.sa Padreng nagsiualat

nitong mabuting sulat,

is that the priest published the book. NagsiuIat implies more

than its literal sense-it makes of the content of the book

something arcane and exclusive but finally made available t o

the general public. Finally, the unifying of five self-contained

stanzas through the use of a central motif is a step in the

direction of organic unity in poetry. This marks the begin-

ning of a break from the improvisational freeness of oral

poetry toward the tightnew of written poetry.

The first Tagalog poet whose name has come down to

us is Pedro Suarez Ossorio, a native of Ermita, whose one

poem appears in the Explicacidn by Santa Ana. Like "May

Bagyo," Osssorio's "Sahmut ~ m Ug a h g Hoyang" (Unending

Thanks) praises the book in which i t appears. The folk

heritage is obvious in its use of the dalit stanza, four mono-

riming octosyllabic lines. Of far greater importance, how-

ever, is the interdependence of the eleven stanzas of the

poem. This is the result of the syntactical relationship of one

stanza with another, as seen in the second and third stanzas:

Ang ito nkang libmng maha1

Na ang lama,i, iyong am1

Iyong tambing tinuiutan

I l i i g at nang marangal.

Nang earning manjja binyagan

May baeahin gabi,t, arao

Na aming pag aaliuan

Dito sa bayan nang lu~nbay.~Z

-- -

This fine book / which contains your message, / You have speed-

32

ily allowed. / To be published and honored. / So that we Christians /

Might have something to read night and day, / Some.&ng to conwle

us / In this valley of tears.

%

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Importantebook Understanding The 40 Parables of Jesus Christ PreviewDocument25 paginiImportantebook Understanding The 40 Parables of Jesus Christ Previewerika padua50% (2)

- Criticism On Commonly Studied Novels PDFDocument412 paginiCriticism On Commonly Studied Novels PDFIosif SandoruÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diary of A Wimpy Kid Tests 70673Document2 paginiDiary of A Wimpy Kid Tests 70673gratielageorgianastoicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Casanova, Giacomo - History of My Life, Books 1 & 2 (Transl. Willard Trask, 1966)Document298 paginiCasanova, Giacomo - History of My Life, Books 1 & 2 (Transl. Willard Trask, 1966)rkgemm777100% (4)

- Philippine Literature in English: Learning ModuleDocument16 paginiPhilippine Literature in English: Learning ModuleKris Jan Cauntic100% (1)

- Reader's Digest India - November 2023Document120 paginiReader's Digest India - November 2023Pranjal JaiswalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dune Frank HerbertDocument1 paginăDune Frank Herbertvladj50% (2)

- The Five Senses in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art - Carl NordenfalkDocument32 paginiThe Five Senses in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art - Carl NordenfalkAntonietta BiagiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transcript of Philippine LiteratureDocument6 paginiTranscript of Philippine LiteratureKimberly Abanto JacobÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 7 2nd QuarterDocument71 paginiModule 7 2nd QuarterKim Joshua Guirre Daño100% (1)

- Cema 7th EditionDocument4 paginiCema 7th Editionsandygituloh0% (8)

- Soviet Heritage 30 IV-6 HaspelDocument181 paginiSoviet Heritage 30 IV-6 HaspelKim Lykke Jørgensen100% (1)

- Everblue by Brenda Pandos PDFDocument2 paginiEverblue by Brenda Pandos PDFCindyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippine LiteratureDocument2 paginiPhilippine LiteratureKatlyn Jan EviaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jose Garcia VillaDocument5 paginiJose Garcia Villamaricon elleÎncă nu există evaluări

- 21st CENTURY LIT (ILOCOS DEITIES)Document2 pagini21st CENTURY LIT (ILOCOS DEITIES)Louise GermaineÎncă nu există evaluări

- World LiteratureDocument20 paginiWorld LiteraturehanniemaelimonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Tales of Tropical GothicDocument3 paginiThe Tales of Tropical GothicMitziel AlfaroÎncă nu există evaluări

- PHIL LIT Syllabus JRCCDocument4 paginiPHIL LIT Syllabus JRCCEsther Joy HugoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Novel Analysis - A Child of Sorrow - AgbayYenDocument10 paginiNovel Analysis - A Child of Sorrow - AgbayYenYen AgbayÎncă nu există evaluări

- NationalisticsDocument3 paginiNationalisticsPedialy AvilesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippine Contemporary Arts: The Beautiful History and Symbolism of Philippine Tattoo CultureDocument17 paginiPhilippine Contemporary Arts: The Beautiful History and Symbolism of Philippine Tattoo CultureJhon Keneth NamiasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week 1 Learning ModuleDocument6 paginiWeek 1 Learning ModuleEllaine Kyle V. RiveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Phil. Lit. During Spanish ColonizationDocument8 paginiPhil. Lit. During Spanish ColonizationKhristel PenoliarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 21st Cen. Lit. Long Quiz ReviewerDocument9 pagini21st Cen. Lit. Long Quiz ReviewerFuntastic PaulÎncă nu există evaluări

- 21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The WorldDocument21 pagini21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The WorldAngelina De AsisÎncă nu există evaluări

- 21st CenturyDocument5 pagini21st CenturyCrystal Anne CastilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Legend and MythDocument33 paginiThe Legend and MythMaria Lou JundisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spanish Colonial PeriodDocument7 paginiSpanish Colonial Periodjezreel ferrerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippine Literature During American Regime: Three Groups of WritersDocument7 paginiPhilippine Literature During American Regime: Three Groups of WritersJEN100% (1)

- Sepang LocaDocument12 paginiSepang LocaRommelyn Salazar100% (1)

- Figures of Speech: Come, Let Me Clutch Thee!Document2 paginiFigures of Speech: Come, Let Me Clutch Thee!Jennica Mae Lpt0% (1)

- Literature of The WorldDocument43 paginiLiterature of The WorldChenna Mae ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pangasinan LiteratureDocument4 paginiPangasinan LiteratureTrisha CorpuzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippine Literary HistoryDocument1 paginăPhilippine Literary HistoryNheru VeraflorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Updated - The Pre-Colonial ERA in Philippine LiteratureDocument13 paginiUpdated - The Pre-Colonial ERA in Philippine LiteratureKris Jan CaunticÎncă nu există evaluări

- Water and or Bodies of Water As Motif in Genevieve Asenjo's Selected PoemsDocument22 paginiWater and or Bodies of Water As Motif in Genevieve Asenjo's Selected PoemsBeiya ClaveriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eng 14 (New Curr.) ModuleDocument66 paginiEng 14 (New Curr.) ModuleIlyn Relampago BacanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World Module 1Document7 pagini21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World Module 1Paby Kate AngelesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Tale of The Three BrothersDocument2 paginiThe Tale of The Three BrothersBridgette Gerona100% (1)

- American Colonial LiteratureDocument39 paginiAmerican Colonial LiteratureSophiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Man ParadoxDocument26 paginiThe Man ParadoxJD0% (1)

- Literature Nestor Vicente Madali Gonzalez: Mika Angela D. Licudo Stem B-2Document1 paginăLiterature Nestor Vicente Madali Gonzalez: Mika Angela D. Licudo Stem B-2MLK LicudoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fernando M. Maramag: The Rural Maid byDocument5 paginiFernando M. Maramag: The Rural Maid byFrencine Agaran TabernaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mahilum Assignment Nay Makaon Ko AswangDocument2 paginiMahilum Assignment Nay Makaon Ko AswangCasper John Nanas MuñozÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abad, Glenford - Dramatic PoetryDocument6 paginiAbad, Glenford - Dramatic Poetryglenford abadÎncă nu există evaluări

- My Clever Pupils: Cheu Ching Kiing Liew Miaw Huei Ting Siew ChingDocument30 paginiMy Clever Pupils: Cheu Ching Kiing Liew Miaw Huei Ting Siew ChingJenny KongyyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Course Outline Phil LitDocument3 paginiCourse Outline Phil LitDarlene De Paz100% (1)

- Pre-Colonial PeriodDocument4 paginiPre-Colonial PeriodJadeyy AsilumÎncă nu există evaluări

- English For Cultural Literacy 7: UNIT I: Expressing Attitudes MeaningfullyDocument36 paginiEnglish For Cultural Literacy 7: UNIT I: Expressing Attitudes MeaningfullyTrisha AliparoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippine Literature InfographicDocument1 paginăPhilippine Literature InfographicfaithevangelcapaciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literature Task - HinilawodDocument1 paginăLiterature Task - HinilawodKia potz100% (1)

- Philippine EpicsDocument2 paginiPhilippine EpicsNico OrdinarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Types of LiteratureDocument3 paginiTypes of LiteratureCorinne ArtatezÎncă nu există evaluări

- A.1.2 Philippine Literary History Spanish Period1Document76 paginiA.1.2 Philippine Literary History Spanish Period1Renzo Macarilay PazziuaganÎncă nu există evaluări

- CW Report Lesson 3Document2 paginiCW Report Lesson 3Eugene BalindanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fr. Bernardino Melendreras, OfM (1815-1867) Florentino HornedoDocument4 paginiFr. Bernardino Melendreras, OfM (1815-1867) Florentino HornedoKurt ZepedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aida RiveraDocument11 paginiAida RiveraRobie Jean Malacura PriegoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Region 7 Presentation - 105707Document7 paginiRegion 7 Presentation - 105707Mark Denzel Laforga100% (1)

- Pathf 3 (Dance) Module 3 Jpadua FinalDocument12 paginiPathf 3 (Dance) Module 3 Jpadua FinalMike Melvin AcostaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eng 4Document19 paginiEng 4Jermie Salceda LaranioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literary CriticismDocument2 paginiLiterary CriticismIsnaeny AriefÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mathematics in The Modern WorldDocument3 paginiMathematics in The Modern WorldTuanda TVsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippine Literature History Timeline: Historical EventsDocument11 paginiPhilippine Literature History Timeline: Historical EventsRedenRosuenaGabrielÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Myth of Bernardo CarpioDocument19 paginiThe Myth of Bernardo CarpioHavanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Timeline in LiteratureDocument16 paginiTimeline in LiteratureJennifer de GuzmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- AuthorDocument3 paginiAuthorElmar GuadezÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Brief Introduction To The Versecraft oDocument60 paginiA Brief Introduction To The Versecraft oBrunoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Poetry Uas NanaDocument12 paginiPoetry Uas NanaBaiq Chunafa Diza FarhanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Understanding JobDocument143 paginiUnderstanding JobStephanie YeungÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stagecoach Journal EntryDocument3 paginiStagecoach Journal EntryAliNIC7Încă nu există evaluări

- List of Required Texts For 1 Years 2017 - 2018: Commentaries, (9Document3 paginiList of Required Texts For 1 Years 2017 - 2018: Commentaries, (9Fatima AtharÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sleeping Beauty Picture Book 1000832532Document60 paginiThe Sleeping Beauty Picture Book 1000832532Ha Ngan DangÎncă nu există evaluări

- The LL of The Mediterranean - French and Italian Coastal CitiesDocument263 paginiThe LL of The Mediterranean - French and Italian Coastal CitiesMonali Saibal Mitra100% (1)

- Trinity Sight Reading Book 1Document31 paginiTrinity Sight Reading Book 1John Apora96% (54)

- Ielts Essay Kiran Makkar PDFDocument4 paginiIelts Essay Kiran Makkar PDFVickeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Life of Sir Walter Ralegh From His Birth To His Death On The Scaffold ...Document589 paginiThe Life of Sir Walter Ralegh From His Birth To His Death On The Scaffold ...Leigh SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- Packing ListDocument2 paginiPacking ListsyrizinhoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Law of The Old Covenant2Document50 paginiThe Law of The Old Covenant2robelinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vertigo Tarot (Book + Cards)Document210 paginiVertigo Tarot (Book + Cards)Natasha Gilligan100% (1)

- ALLAH and Prophet Muhammad (Peace Be Upon Him)Document12 paginiALLAH and Prophet Muhammad (Peace Be Upon Him)Majid KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- ListDocument67 paginiListAna Alexandra Nicolae100% (1)

- Let's Collect Rocks and Shells by Shell Union Oil CorporationDocument21 paginiLet's Collect Rocks and Shells by Shell Union Oil CorporationGutenberg.orgÎncă nu există evaluări

- El Doctor Me Di CinDocument27 paginiEl Doctor Me Di CinTchie Xue100% (1)

- Baby Treatment Based On NDT Principles Baby Treatment Based On NDT PrinciplesDocument2 paginiBaby Treatment Based On NDT Principles Baby Treatment Based On NDT PrinciplesHiten J Thakker0% (1)

- Lesson plan: pictures of animals - Google ПоискDocument7 paginiLesson plan: pictures of animals - Google ПоискАяжанÎncă nu există evaluări

- Islamiat Nts Past PapersDocument3 paginiIslamiat Nts Past PapersRashid aliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Akira Mizuta Lippit Atomic Light Shadow OpticsDocument220 paginiAkira Mizuta Lippit Atomic Light Shadow OpticsMiriam SampaioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sapir, E. y M. Swadesh. 1946. American Indian Grammatical CategoriesDocument11 paginiSapir, E. y M. Swadesh. 1946. American Indian Grammatical CategoriesFab CastilloÎncă nu există evaluări