Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Oxford Handbooks Online: Architecture

Încărcat de

bamca123Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Oxford Handbooks Online: Architecture

Încărcat de

bamca123Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Architecture

Oxford Handbooks Online

Architecture

Edmund Thomas

The Oxford Handbook of Roman Studies

Edited by Alessandro Barchiesi and Walter Scheidel

Print Publication Date: Jun 2010

Subject: Classical Studies, Classical Art and Architecture, Greek and Roman Archaeology

Online Publication Date: Sep 2012 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199211524.013.0054

Abstract and Keywords

Perhaps more than other aspect of Roman culture, the study of architecture is affected by

two preconceptions, the first resulting from its durability, the second from later attitudes.

First, because buildings appear as a solid and visible legacy of Roman culture, it is

assumed that Romans themselves clearly recognised the meaning of architecture. Yet,

within a short time-span, two ancient writers, Varro and Vitruvius, presented different

views. Vitruvius, the more fortunate in transmission, was ambivalent about the definition

of ‘architecture’, calling it first a compound of aesthetic concepts – organisation, layout,

good rhythm, symmetry, correctness, and allocation; but, a chapter later, a combination of

scientific domains – building, mechanics, and orology. For Varro, architecture was one of

nine ‘disciplines’; his lost treatise can hardly have contained such technicalities or

defined ‘architecture’ so comfortably within the parameters of the modern academic

subject. This article explores past debates on Roman architecture, including one

concerning archaeology and architectural history; form and function as well as utility and

ornament of Roman buildings; public architecture and private building; and centre and

periphery.

Keywords: Rome, architecture, buildings, Varro, Vitruvius, archaeology, form, function, centre, periphery

I. Studying Roman Buildings

The buildings of savages, considered on their own merit, have no place in this

book. We are concerned with architecture, that is the ‘monumental building’ of

craftsmen conscious of the beauty of certain forms and eager to heighten and

perpetuate them.

(Plommer 1956: 1)

Page 1 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Cambridge University Library; date: 09 April 2019

Architecture

THE opening to the first volume of Simpson's History of Architectural Development exposes the

fundamental place commonly given to Roman buildings in the civilizing process of European

culture. Behind this view, so alien to today's postcolonial world, lies a more lasting problem.

Perhaps more than other aspect of Roman culture, the study of architecture is affected by two

preconceptions, the first resulting from its durability, the second from later attitudes. First,

because buildings appear as a solid and visible legacy of Roman culture, it is assumed that

Romans themselves clearly recognized the meaning of ‘architecture’. Yet, within a short time-

span two ancient writers, Varro and Vitruvius, presented different views. Vitruvius, the more

fortunate in transmission, was ambivalent about the definition of ‘architecture’, calling it first a

compound of aesthetic concepts—organization, layout, good rhythm, symmetry, correctness, and

allocation (De Arch. 1.2.1), but, a chapter later (1.3.1), a combination of scientific domains—

building, mechanics, and orology. As he treats these unevenly, his original conception of

‘architecture’ plausibly embraced only (p. 839) ‘building’, in six books—specifically, planning,

materials, columnar design, and public and private structures—and was revised to include the

other two sciences in the final ten (Pellati 1947–9). For Varro, architecture was one of nine

‘disciplines’; his lost treatise can hardly have contained such technicalities or defined

‘architecture’ so comfortably within the parameters of the modern academic subject. Roman

architecture defies typologies and taxonomies (Gros 1996–2001: 1. 17). It is unsettling that we

do not know more clearly the boundaries of the science practised by the architecti of Rome.

As the themes of Vitruvius' first six books proved more compelling to the text's

Renaissance interpreters and their patrons, and skills in his other two sciences declined,

‘building’ naturally came to dominate modern conceptions of ‘architecture’. But there are

other, less narrow ways of defining the field. The areas of concern to ancient architects

also included the design of siege-engines, military arsenals, and bridges; the building

activities of emperors and senators embraced roadworks, temporary theatres and

amphitheatres, even ships; the triumphal arches, amphitheatre, and funerary structure

shown on the contractor Haterius' tomb and the villas and painted stage-like structures

on Campanian murals are omitted or peremptorily dismissed by Vitruvius, as are the

geometrical and cosmological interests of the mathematician Archimedes and the

philosopher Thales, whom Lucian ranks alongside the architect Hippias; and Daedalus,

designer of the Minoan labyrinth and symbolic precursor of ancient architects, reportedly

extended his work, like Leonardo, to flying-machines. The gap between the shifting

reality of the ancient discipline and our own limited conception of ‘Roman architecture’ is

remarkable.

The second preconception is more serious. Unlike other varieties of their art, the Romans'

architecture is held to show ‘excellence and originality’ (Kampen 2003: 375). Despite

modern technological advances, scholars still highlight its ‘staggering difficulty, great

expense, and organizational intricacy’ (Taylor 2003: 5), inviting students to contemplate

how such awe-inspiring buildings were completed and specialists to provide answers to

these seemingly unanswerable questions or to evaluate Roman buildings as the highest

achievements of the science. To many engaged in the discipline, questions of language,

meaning, and ideas appear otiose, as if it were impossible today to fathom the minds that

conceived these ‘superhuman’ projects. The priority of most researchers is to understand

‘how it was done’, rather than why. Comparison of architecture with any of the other

realms of the Roman imagination explored in this book highlights the conceptual gap

Page 2 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Cambridge University Library; date: 09 April 2019

Architecture

today between students of those areas and those who study the architecture of the

Romans. It is as if our understanding of Roman epic were limited to metrical analysis or

lexical computation, or studies of political theory addressed only constitutional issues.

Certainly, several scholars of the last twenty years have emphasized not the unequalled

achievement of Roman builders, but the imperfections of their works. The Pantheon is

now regarded as a botched compromise (Davies, Hemsoll, and Wilson Jones 1987) and for

all the romantic associations with Hadrian may have been rebuilt under Trajan instead

(Hetland 2007; Grasshoff et al 2009); the Baths of Caracalla are seen as flawed in the

execution of their design (DeLaine 1997: 64–5); the Oppian wing of Nero's Golden House

is noted for its awkward planning, the main hall of the Trajan's Markets derided as

‘grossly clumsy’ (Ball 2003: 56–61, 272); even the Colosseum is studied not only for its

‘technical perfection’ (Gros 1996–2001: 1. 328), but also for its experimentation

(Lancaster 2005a). Now it is not only classicists who study such buildings; a wide range

of other specialists bring fresh perspectives, including architects, engineers, geologists,

and art historians

Yet, for all the varied skills applied to Roman buildings and the sophistication of the tools

and techniques used to study them, the basic aims of the discipline have changed little

since the days of the Italians Giuseppe Lugli and Luigi Crema or the Germans Richard

Delbrück and Hans Kähler. True, we know more about several important areas: the

modular design of the columnar orders (Wilson Jones 2000); the practicalities and real

costs of large-scale construction projects in terms of materials and manpower (DeLaine

1997); the techniques used to assemble structures of ambitious conception (Giuliani

1990; Lancaster 2005a); the planning in the workshop (Haselberger 1994); and the

sources of materials or logistics of their transportation (Herz and Waelkens 1988). The

depth and variety of these investigations, added to the modern techniques of digital

photography and computer-aided design, mean that the student of ancient Roman

architecture in the early twenty-first century is immeasurably better equipped than her

predecessor fifty years ago. But in overall scope these studies echo the concerns of Lugli,

Crema, and others in foregrounding matters of process and leaving unexplored what

these structures meant to those who conceived or used them.

This focus of modern scholars on pragmatic issues is partly a response to the excesses of

some of their forebears. Those studying Roman buildings in today's post-ironic world feel

liberated from the desire for overarching explanations, which marked the responses of

earlier scholars to the question of meaning in Roman architecture. Grand theories are

now unfashionable. The arguments of the symbolists—Hans Peter LʼOrange (1953), Earl

Baldwin Smith (1956), and Karl Lehmann (1945), who saw domes, arched lintels, and

ornamental column displays as reflecting ideas of political or cosmic hierarchy, associated

with the imperial cult (Yegül 1982)—have been discredited. Considerations of the

symbolic or metaphorical role of architecture (Drerup 1966; Demandt 1982) occupy a

marginal place within the discipline; scepticism is expressed about the occurrence and

significance of such forms (Joyce 1990). Following Richard Krautheimer's warning that

‘symbolic significance … merely accompanied the particular form… chosen for the

Page 3 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Cambridge University Library; date: 09 April 2019

Architecture

structure… as a more or less uncertain connotation which was only dimly visible and

whose specific interpretation was not necessarily agreed upon’ (1942: 9), attempts to

decipher that significance have waned. Down-to-earth motives for urban design are

preferred (Burrell 2006). But, if (p. 841) earlier post festum interpretations of architectural

symbolism are distrusted, one may still seek in Roman buildings, as in medieval

cathedrals, ‘truths ramified, disruptive and multi-layered’ (Crossley 1988: 121).

The triumph of the pragmatists began in Germany, where Delbrück (1907–12) challenged

a prevailing tendency to stereotype Roman architecture as, typically, a thought-world of

arches and vaults presented in self-conscious opposition to the rectilinear buildings of

‘the Greeks’. His insistence on archaeological realities and avoidance of theorizing was

followed by others such as Wolf-Dieter Heilmeyer (1970), for whom techniques of Roman

construction or formal variations in ornament were positivistic data indicating relative

chronology rather than visual expression. If Heilmeyer retained something of the older,

romantic search for the genius architect in attributing Hadrian's Pantheon to the Syrian

Apollodorus (Heilmeyer 1975), that hypothesis was rooted in formalistic analysis, if also

retaining something of the Hegelian impulse to see conceptions of space as reflections of

the spirit. In Italy Lugli (1957) emphasized materials and techniques, focusing on Rome,

while Crema (1959) highlighted type and typology, providing for the first time a global

and historically nuanced view of Roman architecture. John Ward-Perkins refashioned the

subject for British students, revising older works (Anderson and Spiers 1907; Robertson

1943) to stress ‘the essentially practical nature’ of Roman approaches to ‘problems of

construction’ (Ward-Perkins 1973: 51). By contrast with his predecessors, Ward-Perkins

emphasized the architecture of the provinces, albeit without the chronological nuances

applied to the capital. His general account with Axel Boëthius (1970), later revised and

published separately (1981), remains the most authoritative overall treatment of the

subject in English today. Yet a reader of Ward-Perkins's book might be forgiven for

thinking that there were no patrons of provincial Roman buildings and that few ideas

were communicated by these agglomerations of materials spread across the different

European regions.

The sheer range and complexity of Roman architecture create special problems for its

historians, who must decide how to divide their topic: whether chronologically to

emphasize general formal or stylistic developments (Anderson and Spiers 1907); by

geographical area to highlight regional difference (Ward-Perkins 1981); or by building

type to stress the architectural changes that accompanied specific social uses (Gros

1996–2001: 1. 18–21). None of these arrangements is without prejudice. Chronological

approaches overlook not just regional or functional variations, but similarities in meaning

between buildings distant in date, and are vulnerable to the fallacy of linear progression

from the simple to the complex; a regionalist focus cannot easily account for

developments across the whole empire; and typological divisions seem too crude to

explain buildings whose forms were only loosely linked to functions, with labels like

‘atria’ and ‘porticoes’ applied to very different functional realities; for more diversified

Page 4 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Cambridge University Library; date: 09 April 2019

Architecture

buildings like tomb monuments, typologies have little value at all (Gros 1996–2001: 2.

380).

Against the mainstream accent on the application of form to function, some voices

(p. 842)

have attempted to renegotiate the boundaries of the discipline. In France Gilles Sauron

has emphasized the ‘constant relation between decoration and its patrons’, interpreting

the late Republic through an ‘archaeology of looking’ (1994: 13–15). In England John

Onians (1988) explains ancient architecture in terms of rhetoric and psychology rather

than structure and design. Such re-branding of buildings as objects of experience or

media for ideas, rather than solutions to practical problems, has opened challenging new

vistas for students of Roman architecture, which may mirror more closely the ways in

which contemporaries perceived their built environment. But, because their hypotheses

are rejected on empirical grounds and their approaches perceived as detached from

traditional methods, few so far have followed their examples.

On the continent, by contrast, more speculative approaches to meaning in architecture

are securely anchored in formalistic presumptions and procedures. Prominent here are

the German archaeologists Paul Zanker and Henner von Hesberg, and, in France,

especially Pierre Gros (1996–2001). For Hesberg (1990), architectural ornament is not

only a means of dating archaeological monuments, but a ‘leading cultural

form’ (kulturelles Leitform) expressive of its time. The argument has obvious circularity

and some common ground with earlier searches for a Zeitgeist in ancient architecture.

But more concerning is that Hesberg's argument depends on detailed, perhaps

subjective, stylistic analysis of architectural fragments and takes little account of ancient

views on architecture or its decoration. Gros recognizes rhetorical and symbolic uses of

architecture, presenting Roman buildings in a historically nuanced social context. But one

seeks in vain an approach like that of the philosopher Robert Hahn (2001) to archaic

Greek temples, who highlights their relation to pre-Socratic thought, showing how

architecture acted as a dynamic idea in ancient culture, not merely an adjunct or

reflection of it.

In the land of Frank Lloyd Wright, for whom architecture was ‘the scientific art of making

structure express ideas’ (Wright 1941: 141), the search for architectural meaning has

sometimes taken a more abstract direction. Frank Brown revitalized the discipline with

his uniquely penetrating interpretations of meaning. If his analyses of the basic spatial

notions of Roman temples or fora (Brown 1961) may seem as dated today as modernist

skyscrapers in our cities, his brilliant lateral reasoning in recognizing the ‘pumpkins’ of

Hadrian despised by Apollodorus in the gored domes of Tivoli and Baiae (Brown 1964)

will long stand as a model for how architectural remains may be imaginatively and

constructively related to ancient literary sources. Brown's disciple William MacDonald, in

his first book on Roman architecture, highlighted the conceptual implications of the

Roman architectural ‘revolution’ between Nero and Hadrian. Although he stressed that

his emphasis was on direct evidence of standing remains, MacDonald's originality was to

consider them in terms of (p. 843) communication of ideas and human personalities.

‘Masterpieces such as the Pantheon’, he wrote, with barely a hint of Hegelianism, ‘were

Page 5 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Cambridge University Library; date: 09 April 2019

Architecture

above all expressions of immanent cultural forces, and technology, though important, was

a secondary factor in their creation’ (MacDonald 1982: 5).

In his even more innovative second volume (1986), MacDonald discussed characteristics

of urban architecture across the Roman Empire with a fresh vision, replacing dry

typology with evaluations of aesthetic or social meaning. His identification of ‘urban

armatures’ and analysis of ‘cardinal themes’ are so far removed from the historical

context of Roman buildings that this book remains today an art-historical essay, rather

than a true cultural analysis, but his suggestions of common formal properties and modes

of design across the empire need serious contextualization. Others have focused on

mathematical or cosmological aspects of design, especially for the Pantheon itself (Loerke

1990; Sperling 1997; Martines 2000), or analysed the geometry of individual buildings or

even whole cities (Watts and Watts 1992); yet MacDonald's general proposition (1986:

246) that a shift from geometric to arithmetic conceptions informed the use of un-

classical and proto-baroque forms in urban space, invites further investigation. The

contribution of ancient mathematics to reconceptualizing architectural space and its role

in wider cultural change are still to be addressed.

Nevertheless, the last twenty-five years have seen more growth in the study of Roman

architecture than any other similar period, whether measured in terms of empirical

additions to knowledge, expansion into new fields, or adoption of new methodologies. The

material evidence has increased through excavation and topographical research at cities

such as Verona (Frova and Cavalieri Manasse 2005), Carthage (Hurst, Fulford, and

Peacock 1994), and Caesarea Maritima (Holum and Raban 1996). Aided by new,

computer-based techniques, students of architecture attempt serious answers to

questions similar to those asked by other cultural historians: Geographic Information

Systems show how the social character of towns like Pompeii (Laurence 1994) or

Empúries in Spain (Kaiser 2000) is mapped by changes in urban space (Jones and Bon

1997); artefactual analysis highlights how the decoration and use of individual rooms in

Roman houses reflected social realities (Allison 2004); scholars are sensitive to the role of

ideologies (Trillmich and Zanker 1990) in shaping the built environment of antiquity, from

the Augustan transformation of the Athenian Agora ‘down to the wheel-ruts in the paving

stones’ at Pompeii (Wallace-Hadrill 1995). Regional and chronological variations of civic

assembly buildings are not only considered matters of style or typology, but related to

larger, political issues of urban layout (Balty 1991). The architecture of whole regions

from the Levant to Spain is now better understood. The analysis of architectural

ornament has advanced so far in methodology that it is studied no longer only for stylistic

change or variation (Strong 1953; Léon 1970), but in terms of ideal planning (Wilson

Jones 2000) or visual ‘semantics’ (Gros 1989). Ancient (p. 844) architectural terminology is

no longer straightforwardly applied to archaeological remains, but scrutinized and

questioned (Callebat 1995; Leach 1997).

Changes in approach to Vitruvius are symptomatic of the shift in method in Roman

architectural history in general. Many past shortcomings of the subject can be attributed

to the peculiarity of what one might call ‘the Vitruvius problem’. In a field extending

Page 6 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Cambridge University Library; date: 09 April 2019

Architecture

geographically from Britain to Arabia and from the Caucasus to the Atlas Mountains, and

chronologically from the putative Palatine wall of Romulus to Justinian's Santa Sophia, an

anomaly is that the observations and concerns of this military engineer have remained

central to modern constructions of the idea of Roman architecture. Vitruvius grew up in

northern Italy, served in the Roman state service under Julius Caesar in North Africa, and

was probably an example of that parochial, professional middle-class grouping, the

apparitores (Purcell 1983). His only known public commission is the colonial basilica he

describes at Fanum. Modern scholars stress the narrowness and conservatism of his

treatise, its essentially rhetorical purpose, and its omissions or limitations (Le Projet de

Vitruve, 1994). The absence of amphitheatres from his treatise and minimal discussion of

bath-buildings illustrate the work's limited value for explaining archaeological data. The

De Architectura is no longer naively invoked as an authority for constructions of all

historical periods and in all areas of the empire, but examined for its methods and

sources within the narrow cultural context of the late Hellenistic age. Considered more

relevant to second-century BCE Asia Minor than first-century Rome (Ciotta 2003), its

precepts are studied as ideological statements (McEwen 2003). If the ‘Vitruvian’ triad of

beauty, stability, and utility reappears in later contexts (Lucian, Hippias 4) and Vitruvius'

own reputation lasted into the fourth century (Wilson Jones 2000: 35), this may be merely

evidence of the proliferation and resilience of architectural cliché in contemporary

culture rather than a confirmation of his influence on design.

Although modern scholars are not as tied to Vitruvius' words as their predecessors, it will

always be tempting, while his work remains the sole surviving ancient treatise on

architecture, to highlight his precepts, from methods of making Roman concrete (Oleson

et al. 2006: 30–41) to designs of surviving structures (Ros 1997). But the text

overshadows the conception and scope of the discipline more generally. Questions asked

of construction or technique, the privileged status of the columnar orders, the critical

analysis of buildings as diverse as public baths, private houses, and civic basilicas, and

the very labelling of archaeological remains—all owe their conception to the weight given

to such topics in Vitruvius' own treatise. For all the discrepancies between the work's

insularity and modern methodologies, or between its ideas and most extant material

culture, the De Architectura is still heralded as ‘an essential companion’ for enquiries

about Roman design (Wilson Jones 2000: 33).

Yet the questions that architectural writers ask today are different. Thomas Markus

(1993), for example, discusses sociological rather than aesthetic or technological (p. 845)

issues. He sees buildings primarily as social objects, not structural achievements, their

forms as evidence of human identity, power relations, and cultural order, not simply

processes of construction or design. Buildings have social meaning, from their materials

and ornamentation to their functions, uses, and spatial structure. The design and

imagination of the built environment can liberate or confine human lives. In comparison

with such wider socio-cultural issues, many studies of Roman architectural history look

rather limited.

Page 7 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Cambridge University Library; date: 09 April 2019

Architecture

To understand Roman architecture properly as a cultural system, we must rethink the

questions traditionally asked of the subject and ask new ones. The second part of this

chapter therefore reflects on the framing of scholarly debates on Roman architecture in

recent decades. The discipline is dominated by several conceptual oppositions. Ten of

these are presented below. Many are modern, some subject to long-standing controversy,

causing issues to be sharply polarized; all must be redefined to explain subtleties and

nuances in the evidence. Then five alternative oppositions drawn from ancient thinking

are presented which can help shape future research, not to re-polarize debate, but to

introduce new fields of enquiry. Their dialectic reflects the equivocal status of

architecture in Roman culture and throws light on that essential, overriding duality in any

period or style of architecture, the relation between form and meaning. There is no space

here to discuss all fully; but they offer valid thematic paradigms for seeing Roman

architecture in its cultural context and assessing past studies or planning future ones.

II. Rethinking Polarities

A. Past Debates on Roman Architecture

1. Archaeology or Architectural History

Just as the subject area of Roman architecture is diverse and elusive, so the nature of the

modern discipline is hard to pin down, contested on one side by classical archaeologists

and on the other by art or architectural historians (Kampen 2003: 373). For the former,

Roman buildings are one aspect of a variegated material culture requiring interpretation

or explanation; for the latter, what demands attention is the process of design itself. The

methodologies of the two approaches are reconcilable. Without drawings, logbooks,

financial records, or, usually, even architects' names, Roman architectural history is

necessarily focused on archaeological evidence; architects are considered of (p. 846) little

interest when few are known to be connected with more than one building (Lyttelton

1974: 16). Processes of design or construction are inferred from material remains

(DeLaine 1997).

Yet the ultimate goals of archaeologists and architectural historians seem opposed. While

the former explain extraneous processes through architectural evidence, the latter invoke

evidence from beyond the material world to understand structural remains in their

proper historical and social context. The relation between the two disciplines becomes

fluid when scholars shift their focus between the buildings and the cultures or societies

that conceived them. Architectural meaning, both a matter of physical form and a feature

of society, lies inevitably in the nexus between these two domains. Neither archaeologists

nor architectural historians see their principal aim as understanding the meaning or

symbolic significance of Roman buildings for contemporaries. Those with such interests

must adapt methodologically like chameleons, acting now in one role and now in the

other. Without constant disciplinary adjustment and interaction with literary or

epigraphic sources, the traditional focus of philologists or historians, the question of

Page 8 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Cambridge University Library; date: 09 April 2019

Architecture

meaning may disappear. At present, it is often buried in the fertile borderland between

archaeology and architectural history.

2. Form and Function

Roman buildings hardly it the modernist ideal of a perfect match between form and

function. Notions of decor corresponded not to this, but to the expected correlation

between architecture and social rank or religious status: according to this moral

criterion, buildings were approved for suiting the status and image of their owners or

communities; for propriety or moderation in materials, rather than excess. Even Cicero's

famous explanation of the overhanging eaves of the Capitoline Temple (Cic. De Or. 3.18o)

reflects rhetorical special pleading and cannot be taken seriously as a design principle.

Because architectural terminology failed to keep pace with physical changes,

understanding building types from archaeological remains is constantly challenging. The

semicircular blocks of seating found across the Eastern Empire served multiple functions:

as not only theatres, but performance halls, council chambers, and meeeting-places for

other assemblies; in the West, the seats of local government, curiae, are hard to identify

by form alone without their once-typical feature, banks of wooden seats (Balty 1991); and

the many porticoes throughout the empire are not reducible to typologies, but form an ill-

defined category loosely grouped by a common label, which, since its origin from Greek

stoas, had varied applications, from temple porches to street-side colonnades, not easily

reconcilable with a single concept. The modernist ideal is a dubious basis for the

questions asked of Roman architecture.

(p. 847) 3. Utility and Ornament

That principle is often justified by citing the Romans' own concerns: Vitruvius preached

the virtues of stability, attractiveness, and utility; Cato saw orientation towards practical

needs as preventing moral degeneration. The Roman aptitude for utilitarian structures is

interpreted as a reaction against ornate ‘Greek’ architecture. But distinctions between

the ornamental and functional significance of buildings are more rhetorical than real.

With Roman aqueducts, for example: ‘the opposition … has been drawn too starkly;

aqueducts served both purposes, and the symbolic value of public fountains … was

derived both from their appearance and from their value as fountains that people actually

used’ (Wilson 1998: 93).

The temple of Hadrian at Cyzicus was not only ‘the biggest and most beautiful of all

temples’ (Cassius Dio 70.3.4), but had invented ‘devices and supports, which… did not

previously exist in human society’ (Aelius Aristides 26.21). Dio Chrysostom insisted on the

utility of his new public building project at Prusa, despite opponents' claims that it failed

to meet popular needs (47.13-15).

Just as the rhetorician ‘pseudo-Longinus’ advocated a literary grandeur that ‘no longer

falls outside utility and benefit’, public buildings surpassed the monumentality of Nature

by their practical value. Structures of daily use were celebrated as visual adornments and

for their potential durability. Even non-structural columns were not purely decorative: as

Page 9 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Cambridge University Library; date: 09 April 2019

Architecture

ornamenta they had a semantic function, to communicate social distinctions (discrimina)

(Gros 1989).

4. Public Architecture and Private Building

The division of the most recent and thorough handbook on Roman architecture into

separate volumes on public and private architecture (Gros 1996–2001)reflects a long-

standing demarcation of the subject, if one hardly stressed by Vitruvius. But it overlooks

the close links that existed since Republican times between the design of public temples

and that of private domestic buildings. The identification (Boyancé 1940) of ‘Catulus's

temple’ with the round ‘Temple B’ of the Largo Argentina in Rome—the temple of Fortuna

huiusce Diei founded by Q. Lutatius Catulus (consul 102 BCE)—suggests its influence on

the aviary of Varro's villa at Casinum (Coarelli 1983: 201–11; Sauron 1994: 135–67). More

generally, when ‘public buildings’ were almost always results of private patronage, built

on private land, financed with private money, and designed, surely, to the wishes of

private individuals, how valid is the conventional distinction between ‘public buildings’

and ‘private’ ones? The interests of Roman patrons are recognized in notable cases like

Pompey's Theatre or the Forum Augustum, yet virtually ignored in discussions of

provincial architecture. If Cicero and Pliny's letters attest to personal taste in domestic

architecture, why are we less ready to explain similarly the forms of ‘public buildings’?

Where literature or inscriptions illuminate the process of establishing municipal

buildings, the influence of individual patrons on public (p. 848) decision-making is loudly

attested. Archaeological evidence of uncompleted projects, typically explained in

economic or societal terms, may sometimes be the residue of personal conflicts.

5. West and East/Greek and Roman

The division of the architecture of the Roman Empire into ‘western’ and ‘eastern’ factors

is one of the most long-standing oppositions applied to the subject. It overshadows the

analysis of theatres (Sear 2006: 24–5), civic squares (Balty 1991), even domestic

buildings. Geographically based distinctions have some validity. But one might think of a

cultural ‘regionalism’ underlying architectural patronage, rather than purely formal

distinctions. Regional, social, religious, and cultural differences were all reflected in

architecture. Medieval and later buildings are seen in such terms (Clarke and Crossley

2000; Lefaivre and Tzonis 2003).

The assumed contrast between ‘West’ and ‘East’ is rooted in an older polarization

between ‘Greek’ and ‘Roman’ architecture. Airy Greek temples are often implicitly

contrasted with bulky Roman structures. For Franz Wickhoff (1900), the architecture of

the Roman East derived from western designers; conversely, Josef Strzygowski (1901)

observed the insidious influence of ‘eastern’ style on the ‘purity’ of ‘western’ forms. Later

scholars disputed the direction of influence between ‘East’ and ‘West’ (Ward-Perkins

1965), identifying competition between ‘traditional’, eastern architects and Roman

builders seeking to break the mould. Within this polarity lurks the phantom of originality.

The arch and vault, once hailed as Etruscan or Roman ‘inventions’, are now attributed

either to Macedonian architects learning from the ‘East’ (Boyd 1978; Gossel 1980) or

Page 10 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Cambridge University Library; date: 09 April 2019

Architecture

inventive Greek designers, even the philosopher Democritus (Dornisch 1992: 233).

Conversely, eastern churches are believed to originate in Roman civic basilicas. But

obsessions with retrospective aetiologies can obfuscate the contemporary significance of

such forms. In other areas of ancient cultural studies, scholars now think more

constructively of ‘Hellenization’ and ‘Romanization’ not as absolute formal shifts, but as

varieties of ‘code switching’ within Roman culture itself (Wallace-Hadrill 1998).

6. Centre and Periphery

The opposition between ‘metropolitan’ and ‘provincial’ architecture remains prominent

within the agenda of Roman architectural studies. It has especially dogged discussions of

architectural ornament. Donald Strong (1953) saw the influence of ‘provincial’ workshops

on the architectural decoration of the capital, but Volker Strocka (1988) argued that such

influence was in the reverse direction. Distinctions between ‘metropolitan’ and ‘regional’

styles still dominate work on materials and design. Ward-Perkins established the

orthodoxy that provincial (p. 849) buildings were poorer versions of those in Rome, with

inferior materials or artists and a ‘time lag’ following the introduction of similar forms at

Rome. That is now questionable. If vaulted buildings appear later in Asia Minor and Syria

than Rome, and with inferior materials to Roman concrete (Dodge 1990), the long urban

traditions of these regions ensured that other innovations in design such as the ‘arcuated

lintel’ arrived here soonest. An offshoot of the revelations that the Porticus Aemilia at

Rome is not the barrel-vaulted structure formerly assumed to bear that name (Cozza and

Tucci 2006) is that Rome actually lagged behind other Italian cities in the development of

concrete architecture (Lancaster 2005a: 5). Even during the Empire, it was often Italy

that learned from other regions, rather than the reverse.

Provincial buildings were no mere ‘replications’ of Roman archetypes (MacMullen 2000:

126), like the American embassies that President Truman wanted built across the world

as exact reproductions of the White House (Crossley 1988: 116). Architectural form was a

blend of ‘Roman’ and ‘provincial’ elements. The duality of centre and periphery was not a

polar opposition, but an area of interchange (Champion 1995).

7. Republic and Empire

For provincial architecture the Augustan period is commonly regarded as one of decisive

change. Ward-Perkins saw ‘very little that was Roman, in the narrower, Italian sense of

the word’, in earlier western municipal architecture (1970: 18). The existence of

Vitruvius' treatise and his omission of many forms of Imperial architecture have

encouraged the recognition of a dichotomy between Republican buildings and those of

the Empire. But there is no simple contrast in Roman concrete construction between

‘experimental’ forms in the late Republic and structurally more ‘advanced’ works of the

early Empire, nor any linear development in architectural technology. The early terraced

sanctuaries of Latium are more ‘developed’ in their uses of concrete and spatial forms

than most buildings in first-century Italy. If the ‘standardization’ of the Corinthian order

under Augustus established a model for later temples (Gros 1996–2001: 2. 470–503), it

relied on substantial development of the form during the previous century (Wilson Jones

Page 11 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Cambridge University Library; date: 09 April 2019

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Construction of FacadesDocument5 paginiConstruction of FacadesGunjan UttamchandaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electric Wires and CablesDocument9 paginiElectric Wires and Cableswafikmh4Încă nu există evaluări

- Politics of Space Mary McLeodDocument9 paginiPolitics of Space Mary McLeodbamca123Încă nu există evaluări

- Architectural Styles and MovementsDocument2 paginiArchitectural Styles and MovementsYessaMartinez100% (1)

- Studies in Tectonic CultureDocument446 paginiStudies in Tectonic CultureTeerawee Jira-kul100% (29)

- Typo Logical Process and Design TheoryDocument178 paginiTypo Logical Process and Design TheoryN Shravan Kumar100% (3)

- Jacoby - Type Vs TypologyDocument27 paginiJacoby - Type Vs Typologyfour threeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Duct Sizing-Static BalanceDocument24 paginiDuct Sizing-Static BalancemohdnazirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Studies in Tectonic Culture PDFDocument14 paginiStudies in Tectonic Culture PDFF AÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wallace-Hadrill, 2008 - Building Roman IdentityDocument70 paginiWallace-Hadrill, 2008 - Building Roman IdentityGabriel Cabral Bernardo100% (1)

- 1097 - Architecture of Emptiness PDFDocument18 pagini1097 - Architecture of Emptiness PDFRaluca GîlcăÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theory of ArchitectureDocument21 paginiTheory of Architecturedaniel desalegnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alberto Perez-Gomez - Stephen Parcell-Chora 4 - Intervals in The Philosophy of Architecture-Mcgill Queens Univ PR (2004) PDFDocument353 paginiAlberto Perez-Gomez - Stephen Parcell-Chora 4 - Intervals in The Philosophy of Architecture-Mcgill Queens Univ PR (2004) PDFkhurshidqÎncă nu există evaluări

- BANHAM Reyner, StocktakingDocument8 paginiBANHAM Reyner, StocktakingRado RazafindralamboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Architecture Notes PDFDocument259 paginiArchitecture Notes PDFVinothÎncă nu există evaluări

- C G Malacrino Constructing The Ancient WorldDocument6 paginiC G Malacrino Constructing The Ancient WorldÖzkan ORALÎncă nu există evaluări

- Frampton Studies in Tectonic Culture 1995 P 1 12 Email PDFDocument14 paginiFrampton Studies in Tectonic Culture 1995 P 1 12 Email PDFviharlanyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thematic Theories of ArchitectureDocument26 paginiThematic Theories of ArchitectureEllenor ErasanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Space in ArchitectureDocument7 paginiSpace in Architectureicezigzag100% (1)

- 建构文化研究书评3Document5 pagini建构文化研究书评3weareyoung5833Încă nu există evaluări

- Structural Rationalism During The Age of EnlightenmentDocument22 paginiStructural Rationalism During The Age of EnlightenmentPrashansaSachdeva13100% (3)

- Clas 122 Roman Construction Techniques Oxfordhb-9780199734856-E-11Document28 paginiClas 122 Roman Construction Techniques Oxfordhb-9780199734856-E-11Sam CharafÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artigo - German TectonicsDocument13 paginiArtigo - German TectonicsMárcia BandeiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parameters That Contribute To The Genesis of Architectural StylesDocument7 paginiParameters That Contribute To The Genesis of Architectural StyleszarinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A4429-1 Fall 2019 Kenneth FramptonDocument5 paginiA4429-1 Fall 2019 Kenneth FramptonandiwidiantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- MUÑOZ, James Omar - RESEARCH PAPERDocument10 paginiMUÑOZ, James Omar - RESEARCH PAPERJames Omar MuñozÎncă nu există evaluări

- English For Architects National School of Architecture Semester Two INSTRUCTOR: PR - Saadani 15 MAY 2020Document4 paginiEnglish For Architects National School of Architecture Semester Two INSTRUCTOR: PR - Saadani 15 MAY 2020Uto NarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summerson PDFDocument11 paginiSummerson PDFJulianMaldonadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art History Supplement, Vol. 3, No. 1, January 2013Document73 paginiArt History Supplement, Vol. 3, No. 1, January 2013Leca RaduÎncă nu există evaluări

- Architecture HistoyDocument5 paginiArchitecture HistoyKyronne Amiel PeneyraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modern Architecture (International Style)Document6 paginiModern Architecture (International Style)danielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Structural Rationalism 124235253896Document2 paginiStructural Rationalism 124235253896Madhushree RÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theory - and For Whom?Document9 paginiTheory - and For Whom?Maurício LiberatoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Form FunctionRelationshipArchNature16Document21 paginiForm FunctionRelationshipArchNature16Jana KhaledÎncă nu există evaluări

- Share Pictures O1Document13 paginiShare Pictures O1daniel desalegnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 3.4 Etruscan and Roman ArchitectureDocument19 paginiUnit 3.4 Etruscan and Roman ArchitecturelolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pattern Language - Design Method - Aleksander T. ŚwiątekDocument6 paginiPattern Language - Design Method - Aleksander T. ŚwiątekAlexSaszaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ReceptionClassArch FINAL Feb2017-1Document33 paginiReceptionClassArch FINAL Feb2017-1Juan Luis BurkeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 1 IntroductionDocument56 paginiLecture 1 IntroductionRohit JainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Charles Jencks and The Historiography of Post ModernismDocument19 paginiCharles Jencks and The Historiography of Post ModernismAliaa Ahmed ShemariÎncă nu există evaluări

- # 116524 Modern Architecture RevisedDocument19 pagini# 116524 Modern Architecture RevisedAnonymous KSNHiZcÎncă nu există evaluări

- E34 2Document16 paginiE34 2lauralietoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mark Wilson Jones - Wikipedia PDFDocument3 paginiMark Wilson Jones - Wikipedia PDFsantiagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Estudos em Cutltura Tectônica - FramptonDocument5 paginiEstudos em Cutltura Tectônica - FramptonMarcio LimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- X 024 Deconstructivist ArchitectureDocument9 paginiX 024 Deconstructivist ArchitectureakoaymayloboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Colin Rowe: Space As Well-Composed Illusion: Christoph SchnoorDocument22 paginiColin Rowe: Space As Well-Composed Illusion: Christoph SchnoorVlayvladyyPratonsconskyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fori Report 2014 Introduction Comments1 PDFDocument7 paginiFori Report 2014 Introduction Comments1 PDFAntonio Lopez GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nature of Tectonics and Structural DesignDocument9 paginiNature of Tectonics and Structural DesignAli FurqoniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vitruvius The Ten Books On ArchitectureDocument6 paginiVitruvius The Ten Books On ArchitectureIvy Joy BelzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Myth of DaedalusDocument5 paginiThe Myth of DaedalusOrangejoeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adams 1994Document3 paginiAdams 1994Mercedes Dello RussoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fractal Architecture Michael J. OstwaldDocument11 paginiFractal Architecture Michael J. OstwaldTeodorescu Cezar Liviu AndreiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anderson - Architectural History in Schools of ArchitectureDocument10 paginiAnderson - Architectural History in Schools of ArchitectureArmando RabaçaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ἀρχιτέκτων ἀρχι τέκτων planning designing constructing buildings works of artDocument14 paginiἀρχιτέκτων ἀρχι τέκτων planning designing constructing buildings works of artRemya R. KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presentation 4Document2 paginiPresentation 4privatedhafnecomÎncă nu există evaluări

- DOXIADIS - Sobre Els Assentaments de L'antiga Grècia (Selecció)Document42 paginiDOXIADIS - Sobre Els Assentaments de L'antiga Grècia (Selecció)Joaquim Oliveras MolasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Architecture: For Other Uses, See - Further InformationDocument10 paginiArchitecture: For Other Uses, See - Further InformationshervinkÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1425750Document13 pagini1425750Fabrizio BallabioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sérgio Ferro Concrete As WeaponDocument19 paginiSérgio Ferro Concrete As WeaponGiselle MascarenhasÎncă nu există evaluări

- V Architecture - ReinaDocument14 paginiV Architecture - ReinaRyan Belicario BagonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tom Avermaete Voir Grille CIAM AlgerDocument15 paginiTom Avermaete Voir Grille CIAM AlgerNabila Stam StamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toward A Theory of The Architectural ProgramDocument16 paginiToward A Theory of The Architectural ProgramektaidnanyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eliminating The Gap Between Society and Architecture - Towards An Anthropological Theory of ArchitectureDocument18 paginiEliminating The Gap Between Society and Architecture - Towards An Anthropological Theory of ArchitectureEvie McKenzieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Posmodern UrbanismDocument24 paginiPosmodern Urbanismbamca123Încă nu există evaluări

- The Library As Heterotopia: Michel Foucault and The Experience of Library SpaceDocument19 paginiThe Library As Heterotopia: Michel Foucault and The Experience of Library Spacebamca123Încă nu există evaluări

- Stirling Expositions PDFDocument28 paginiStirling Expositions PDFbamca123Încă nu există evaluări

- Soviet Heritage 35 v-5 GinzburgDocument4 paginiSoviet Heritage 35 v-5 Ginzburgbamca123Încă nu există evaluări

- Fchgfchgq-Manual 3Document20 paginiFchgfchgq-Manual 3Francis Ross NuevaÎncă nu există evaluări

- House Doctor Everyday 10Document69 paginiHouse Doctor Everyday 10vanessa pinedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Econ Ball Valves Carbon Steel Stainless SteelDocument1 paginăEcon Ball Valves Carbon Steel Stainless SteelChristianGuerreroÎncă nu există evaluări

- South Indian Inscriptions Vol. 01Document199 paginiSouth Indian Inscriptions Vol. 01self_sahajaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Technical GuideDocument16 paginiTechnical GuideSMO979Încă nu există evaluări

- The Little Explorer 2012Document2 paginiThe Little Explorer 2012Meg McKenzieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Landa SJ100A Parts Washer ManualDocument28 paginiLanda SJ100A Parts Washer ManualNeal Bratt100% (2)

- Information Technology VocabularyDocument2 paginiInformation Technology VocabularyCasa NaluÎncă nu există evaluări

- تحليل Stratford Skyscraper SOMDocument7 paginiتحليل Stratford Skyscraper SOMJARALLAH ALZHRANIÎncă nu există evaluări

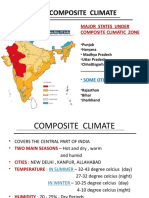

- Composite Climate: Major States Under Composite Climatic ZoneDocument25 paginiComposite Climate: Major States Under Composite Climatic ZoneSporty Game100% (1)

- The Chow CollectionDocument51 paginiThe Chow CollectionStephen ChowÎncă nu există evaluări

- HTML Kodları-Tr - GG - Sitene Ekle - Ana SayfaDocument85 paginiHTML Kodları-Tr - GG - Sitene Ekle - Ana SayfaKenan ÇankayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Any BusDocument4 paginiAny BusgreggherbigÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sustainable Development Aditya SharmaDocument9 paginiSustainable Development Aditya SharmaAditya Sharma0% (1)

- Tivoli Access Manager Problem Determination Using Logging and Tracing FeaturesDocument41 paginiTivoli Access Manager Problem Determination Using Logging and Tracing FeaturescotjoeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Flex Appliance Getting Started and Administration Guide - 1.0Document60 paginiFlex Appliance Getting Started and Administration Guide - 1.0toufique shaikhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Etsi Eg 202 057-1Document34 paginiEtsi Eg 202 057-1Dusan JokanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study PresentationDocument12 paginiCase Study PresentationParvathi MurukeshÎncă nu există evaluări

- VoQuangHai CVDocument6 paginiVoQuangHai CVvietechnoÎncă nu există evaluări

- OneExpert CATV ONX630 DatasheetDocument20 paginiOneExpert CATV ONX630 DatasheetJhon Jairo CaicedoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lateral Stability of Boundary WallsDocument2 paginiLateral Stability of Boundary WallsHansen YinÎncă nu există evaluări

- FM Local ChandpurDocument14 paginiFM Local ChandpurShaiful IslamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cable Armado Nema RV1-2004Document36 paginiCable Armado Nema RV1-2004DELMAR QUIROGA CALDERONÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crash 2024 01 21 - 19.30.17 ClientDocument4 paginiCrash 2024 01 21 - 19.30.17 Clientromaindu35.officielÎncă nu există evaluări

- ARK Homes: Project ProfileDocument2 paginiARK Homes: Project ProfilebaluchakpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hettich FinalDocument44 paginiHettich FinalManik LatawaÎncă nu există evaluări

- E1 Install GuideDocument31 paginiE1 Install GuideRahul JaiswalÎncă nu există evaluări