Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The Western Influence On Late Byzantine Aristotelian Commentaries PDF

Încărcat de

Anonymous OpjcJ3Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Western Influence On Late Byzantine Aristotelian Commentaries PDF

Încărcat de

Anonymous OpjcJ3Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Bibliotheca

11

Greeks, Latins, and

Intellectual History

1204-1500

Edited by

Martin Hinterberger and

Chris Schabel

PEETERS

LEUVEN - PARIS - WALPOLE, MA

2011

93690_Hinterberger_RTPM_vw.indd III 21/03/11 09:24

CONTENTS

Preface ...................................................................................... 1

Introduction.............................................................................. 5

The Byzantines and the Rise of the Papacy: Points for Reflection

1204-1453 ......................................................................... 19

Aristeides Papadakis

Repercussions of the Second Council of Lyon (1274): Theological

Polemic and the Boundaries of Orthodoxy ......................... 43

Tia M. Kolbaba

The Controversy over the Baptismal Formula under Pope

Gregory IX ......................................................................... 69

Yury P. Avvakumov

The Quarrel over Unleavened Bread in Western Theology, 1234-

1439 .......................................................................................... 85

Chris Schabel

A Neglected Tool of Orthodox Propaganda? The Image of the

Latins in Byzantine Hagiography ...................................... 129

Martin Hinterberger

Les Prêcheurs, du dialogue à la polémique (XIIIe - XIVe siècle).. 151

Claudine Delacroix-Besnier

What Did the Scholastics Know about Greek History and Culture? 169

Sten Ebbesen

Hidden Themes in Fourteenth-Century Byzantine and Latin

Theological Debates: Monarchianism and Crypto-Dyophy-

sitism.................................................................................. 183

György Geréby

Cypriot Astronomy around 1350: A Link to Cremona? ............ 213

Fritz S. Pedersen

Textes spirituels occidentaux en grec: les œuvres d’Arnaud de

Villeneuve et quelques autres exemples .............................. 219

Antonio Rigo

93690_Hinterberger_RTPM_vw.indd 3 21/03/11 09:24

4 CONTENTS

Divided Loyalties? The Career and Writings of Demetrius

Kydones ............................................................................... 243

Judith R. Ryder

Palamas Transformed. Palamite Interpretations of the Distinction

between God’s ‘Essence’ and ‘Energies’ in Late Byzantium... 263

John A. Demetracopoulos

The Western Influence on Late Byzantine Aristotelian Com-

mentaries................................................................................ 373

Katerina Ierodiakonou

Lateinische Einflüsse auf die Antilateiner. Philosophie versus

Kirchenpolitik ........................................................................ 385

Georgi Kapriev

Manuel II Palaeologus in Paris (1400-1402): Theology, Diplo-

macy, and Politics .................................................................. 397

Charalambos Dendrinos

Greeks at the Papal Curia in the Fifteenth Century: The Case of

George Vranas, Bishop of Dromore and Elphin ................. 423

Jonathan Harris

Index nominum ........................................................................ 439

Index codicum manuscriptorum ............................................... 461

93690_Hinterberger_RTPM_vw.indd 4 21/03/11 09:24

THE WESTERN INFLUENCE

ON LATE BYZANTINE ARISTOTELIAN COMMENTARIES1

Katerina IERODIAKONOU

The obvious place to detect a Western influence on late Byzantine

Aristotelian commentaries is George Scholarios Gennadios’ extensive

logical commentaries on the Ars Vetus, that is to say his commentar-

ies on Porphyry’s Isagoge and on Aristotle’s Categories and De inter-

pretatione.2 For Sten Ebbesen’s and Jan Pinborg’s 1982 article

“Gennadios and Western Scholasticism”3 succeeded in establishing,

beyond any doubt, a strong dependence of Gennadios’ logical com-

mentaries on Latin sources. In particular, they convincingly argued

that large chunks of Gennadios’ comments are nothing but mere

translations from the Quaestiones super Artem Veterem by Radulphus

Brito (ca. 1270-ca. 1320), a scholastic philosopher and theologian

from Brittany who taught Aristotelian logic at the University of Paris

around the beginning of the fourteenth century.4

1. This paper would not have been written if it were not for the insightful work of

Sten Ebbesen in this scholarly field. Moreover, this paper would not have had its present

form if it were not again for Sten Ebbesen’s invaluable comments on an earlier draft. For

these reasons I would like to thank him wholeheartedly.

2. On Gennadios’ life and works see generally F. TINNEFELD, “Georgios Gennadios

Scholarios”, in: C.G. CONTICELLO and V. CONTICELLO (eds.), La théologie byzantine et sa

tradition, II (XIIIe-XIXe s.), Turnhout 2002, pp. 477-549 (with rich bibliography and an

annotated list of Gennadios’ works).

3. S. EBBESEN and J. PINBORG, “Gennadios and Western Scholasticism: Radulphus

Brito’s Ars vetus in Greek Translation”, in: Classica et Mediaevalia 33 (1981-82), pp. 263-

319.

4. On Radulphus Brito, see recently W.J. COURTENAY, “Radulphus Brito, Master of

Arts and Theology”, in: Cahiers de l’Institut du Moyen-Âge Grec et Latin 76 (2005),

pp. 131-158. His works will be listed in a forthcoming fascicle of Olga WEIJERS’ Le travail

intellectuel à la Faculté des arts de Paris: textes et maîtres (ca. 1200-1500), Studia Artis-

tarum, Brepols: Turnhout. Among them are question commentaries on the whole of the

Organon, Metaphysics and Nicomachean Ethics. For a list of his questions on the Organon,

cf. J. PINBORG, “Die Logik der Modistae”, in: Studia Mediewistyczne 16 (1975), pp. 39-97;

rp. in J. PINBORG, Medieval Semantics. Selected Studies on Medieval Logic and Grammar,

ed. S. EBBESEN, London 1984. Radulphus Brito’s Quaestiones super Artem Veterem were

first printed in Venice ca. 1499, but there is no critical edition of the entire text.

93690_Hinterberger_13_Ierodiakonou.indd 373 21/03/11 10:30

374 KATERINA IERODIAKONOU

My aim here is simply to reappraise the extent of such an influence,

to try to understand the rationale behind it, and finally to make some

brief remarks about its further impact.

Let me first introduce the text on which I want to focus. Genna-

dios’ logical commentaries were edited in Paris in 1936 on the basis

of three autographa as the first and biggest part of the seventh volume

of Gennadios’ complete works.5 The editors dated them around

1432/5, though more recently Theodore Zissis has suggested that the

date of their composition could be somewhat earlier.6 The three com-

mentaries cover approximately the same length — 106 pages on

Porphyry’s Isagoge, 123 on Aristotle’s Categories, 110 on the De inter-

pretatione —, and constitute the longest Byzantine commentaries on

these particular logical treatises of Aristotle.7 They were most probably

meant to be used for teaching purposes, perhaps covering the logical

training of students during their first year of philosophical studies.8

But what about the other treatises of the Organon which were usu-

ally taught as part of the standard Byzantine philosophical curricu-

lum? Did Gennadios produce any commentaries on them, too? In the

letter with which he prefaced his extant logical commentaries and in

which he dedicated them to the last Byzantine emperor, Constantine

Palaeologos, who at the time was still residing in Mystra, Gennadios

insinuated that he had no interest in commenting on the Prior Analyt-

ics, because he considered this Aristotelian treatise too technical for

his purposes (4.33).9 Concerning now the Posterior Analytics, Gen-

nadios reported in some length that he had decided, instead of com-

menting himself on it, to translate Thomas Aquinas’ commentary

(4.29-5.12); this translation, however, is unfortunately lost.10 On the

5. Oeuvres complètes de Gennade Scholarios, ed. by L. PETIT, X.A. SIDERIDÈS, and

M. JUGIE, 8 vols., Paris 1928-36.

6. Cf. T.N. ZISSIS, Gennádiov B’ Sxoláriov, Thessaloniki 1980, p. 353.

7. Respectively pp. 7-113, 114-237, and 238-348 of Oeuvres complètes de Gennade

Scholarios, vol. VII, ed. by L. PETIT, X.A. SIDERIDÈS, and M. JUGIE.

8. Cf. ZISSIS, Gennádiov B’ Sxoláriov, p. 353. Zissis makes a much more concrete

suggestion: assuming that the students met for two hours twice a week and studied at each

meeting one of the lectiones into which these commentaries are divided, the three com-

mentaries could have covered the logical course of a whole year in three terms. However,

he does not adduce any textual evidence to support this suggestion.

9. The numbers in parentheses refer to page and line numbers in Oeuvres complètes de

Gennade Scholarios, vol. VII, ed. PETIT, SIDERIDÈS, and JUGIE.

10. Cf. JUGIE’s introduction to Oeuvres complètes de Gennade Scholarios, vol. VII,

p. II.

93690_Hinterberger_13_Ierodiakonou.indd 374 21/03/11 10:30

THE WESTERN INFLUENCE 375

other hand, there is plenty of evidence that Gennadios’ translation of

Aquinas’ comments on the Posterior Analytics was just one instance of

his more ambitious project to translate into Greek important logical

commentaries and textbooks from the Western scholastic tradition.

We have, for instance, his translations of Pseudo-Aquinas’ De fallaciis,

of Peter of Spain’s Summulae logicales (less the treatise on fallacies),

and the anonymous Liber de sex principiis, which in his time was

commonly attributed to Gilbert de la Porrée.11

Still, the Western influence on Gennadios’ logical endeavours was

not limited to the production of these translations. What is more

intriguing, from our point of view, is the way Gennadios tried to

incorporate in his own logical writings what he regarded as Western

wisdom; and it is indicative what he himself had to say about this in

his dedicatory letter to Constantine Palaeologos. More specifically,

there are three points which are worth making in this connection:

(1) Although Gennadios usually did not refer to his sources, he

explicitly mentioned in these prefatory remarks the ancient commen-

tators whose works he was well acquainted with and confessed to have

used, namely, Theophrastus, Alexander, Porphyry, Syrianus, Ammo-

nius, Simplicius and Themistius. Most interestingly, he also referred

to Avicenna, to Averroes and to the Latin scholars whose logical com-

mentaries he claimed to have found useful for the composition of his

own comments12 (3.4-22).13 He even stressed that it is exactly this

11. Oeuvres complètes de Gennade Scholarios, vol. VIII, pp. 255-282, 283-337, and

338-350. It is now accepted that Gilbert did not author the Liber de sex principiis: see

L.O. NIELSEN, Theology and Philosophy in the Twelfth Century. A Study of Gilbert Porreta’s

Thinking and the Theological Expositions of the Doctrine of the Incarnation during the Period

1130-1180, Leiden 1982, p. 45. The three Latin treatises have now been critically edited:

PSEUDO-AQUINAS, De fallaciis ad quosdam nobiles artistas, ed. by R. MANDONNET and P. PETRI,

in S. Thomae Aquinatis Opuscula Omnia, vol. 4, Paris 1927, pp. 508-534; PETER OF SPAIN,

Tractatus, called afterwards Summulae logicales, ed. by L.M. DE RIJK, Assen 1972; Liber

de sex principiis, ed. by L. MINIO-PALUELLO (Aristoteles Latinus, 1/7), Paris 1966.

12. Though in his prefatory letter Gennadios does not refer to any of his Western

sources in particular, in the main text of his logical commentaries we find scattered refer-

ences to Boethius, Aquinas, (pseudo-) Gilbert de la Porrée, Albert the Great and once to

Radulphus Brito.

13. ˆEhßtoun dè oû toùv äploustátouv, toútouv d® toùv tòn ˆAristotelikòn êzjtakótav,

ÿn’ oÀtwv e÷pw, floión (aûtoùv gàr æçmjn m¢llon ärmóttein to⁄v parérgwv êpixeiroÕsi

filosofíaç kaì dózjv eÿneka mónjv, kaì aûtoùv oÀtw kaì êk toioútwn logism¬n ™mménouv

toÕ prágmatov), âllà toùv sofwtátouv te kaì âkribestátouv, oŸ t®n ênteriÉnjn kaì tòn

karpòn aûtoí te êzéspasan kaì to⁄v ãlloiv ∂dwkan xr±sqai, toùv perì Qeófraston kaì

ˆAlézandron légw, Æ perì Porfúrion kaì Surianòn kaì Simplíkion. ‰Estjn dè oûdè méxri

93690_Hinterberger_13_Ierodiakonou.indd 375 21/03/11 10:30

376 KATERINA IERODIAKONOU

dependence on the non-Greek commentators which may be said to

add extra value to his commentaries, as compared with teaching based

on the works of Leo Magentenos, Michael Psellos and John Philo-

ponus14 (3.31-34).15

(2) Gennadios clearly stated that the Latin logical works were par-

ticularly instructive to him both in terms of their content and in

terms of their method. He thought that some of the issues which the

Latins had previously raised, some of the views which they had

expressed, and some of the distinctions which they had made were

more sophisticated than the ones to be found in the Greek commen-

taries. Thus, according to Gennadios, the Latin commentators man-

aged two things; namely, (i) to overshadow (apekrupsan) some of the

interpretations of the ancient commentators by introducing more

subtle distinctions and better observations, and (ii) to develop (epêuk-

sêsan) Aristotle’s philosophy with their additions (3.22-30).16 More-

over, Gennadios explained that the way he chose to structure and

present his comments closely followed that of the scholastic tradition

in dividing the text into ‘lessons’ (anagnôseis ≈ lectiones) and each les-

son into an introduction (protheôria); then a broad analysis of the text

into sections (hê tou grammatos diairesis genikôs ≈ divisio litterae in

toútwn, âllà kaì t®n üperórion sofían, légw dè t®n Latínwn, sumbale⁄sqaí moi pròv tòn

skopòn málista üpeiljfÉv, êpeì t±v Latínwn fwn±v êtúgxanon êpañwn, oûk ôlígav êp±lqon

bíblouv latinikáv, pollàv mèn t±v ârxaiotérav, oûk êláttouv dè t±v mésjv, pleístav dè

t±v newtérav taútjv kaì âkribestérav aïrésewv· oï gàr t¬n Latínwn didáskaloi oΔte t¬n

Porfuríou te kaì ˆAlezándrou kaì ˆAmmwníou kaì Simplikíou kaì Qemistíou kaì t¬n

toioútwn ©gnójsan, kaì ∂ti tà ˆAberóou kaì ˆAbinkénou kaì poll¬n ãllwn ˆArrábwn te kaì

Pers¬n eîv t®n ºljn filosofían suggrámmata eîv t®n ëaut¬n metabebljména fwn®n

†panta prosanégnwn· ˆAberójn dè oûdeív, o˝mai, âgnoe⁄ t¬n êzjgjt¬n ˆAristotélouv ∫nta

tòn krátiston, kaì oûk êzjgjt®n mónon, âllà kaì poijt®n poll¬n lógou kaì spoud±v âzíwn

biblíwn.

14. It is interesting to note that Gennadios includes Philoponus in the same list

together with Magentenos and Psellos and not among the ancient commentators.

15. TaÕta toínun †panta êpelqÉn, eî mèn êkérdaná ti kaì aûtòv pléon t¬n Magentjnón,

Æ Cellón, Æ Filóponon mónon ên to⁄v toioútoiv prostjsaménwn, t¬ç Qe¬ç xáriv t±v dwre¢v·

êkeínou gàr toÕto d¬ron ânamfisbjtßtwv.

16. ÊAte oŒn êk poikíljv sofíav tà kállista sullezámenoi kaì pollà par’ ëaut¬n

êzeuróntev, ofia eîkóv êstin (tí gàr ãllo kérdov génoit’ ån toÕ pollà maqe⁄n Æ tò êzeure⁄n

pollà kaì kalà dúnasqai;), polla⁄v mèn prosqßkaiv t®n ˆAristotelik®n filosofían

êpjúzjsan, pleíosi dè kaì ücjlotéroiv hjtßmasí te kaì qewrßmasi kaì diairésesi lep-

totátaiv tàv t¬n ™metérwn kaì prÉtwn êzjgjt¬n âpékrucan êzjgßseiv. Taûtòn dé ti kaì

aûtoì pepónqasin ên sfísin aûto⁄v· oï gàr Àsteroi kaì ên aûto⁄v diá ge tà aûtà toùv pro-

térouv pareljlúqasin.

93690_Hinterberger_13_Ierodiakonou.indd 376 21/03/11 10:30

THE WESTERN INFLUENCE 377

generali); then a detailed analysis of the text into sections (diaireitai

to gramma eidikôs ≈ divisio in speciali) with interpretations of particu-

lar points (hermêneia ≈ expositio); and finally, ‘investigations’ (zêtê-

mata ≈ quaestiones) that he also structured in the Western way, by

first stating the problem to be discussed, then arguing against the view

expounded, and in the end settling the argument (5.13-26).17

(3) Gennadios expressed the wish to be read not only by his

Byzantine contemporaries but also by the Latins (6.6-9). In fact,

Bonifacio Bembo of Brescia translated part of his commentaries into

Latin during his time.18 It is also indicative that one of the autographa

of his logical commentaries belonged to Cardinal John Salviati (1490-

1553), the nephew of Pope Leo X, active in the first half of the six-

teenth century.19

According to Ebbesen and Pinborg, these prefatory remarks might

suggest that Gennadios’ logical commentaries are fairly independent

works in which “the author takes advantage of his vast reading and

reaps the fruits of Western scholarship without following any par-

ticular source slavishly”.20 But such an expectation is, in their view,

hardly fulfilled. For as I have said at the beginning, they actually

identify the Latin logical work which Gennadios translated and incor-

porated in his comments, namely Radulphus Brito’s Quaestiones super

Artem Veterem. Furthermore, Ebbesen and Pinborg claim that, if we

were to subtract the passages that stem from Brito, what is left from

17. ˆEzjgßsasqai mèn oŒn, ºper e˝pon, t±v logik±v mérov toútwn eÿneka oûx eïlómjn·

eîv dè t®n Porfuríou Eîsagwg®n kaì t¬n déka Katjgori¬n tò biblíon kaì tò Perì

ërmjneíav, ° d® kaqáper tiv qeméliov t±v perì sullogism¬n pragmateíav kaì filosofíav

äpásjv e˝nai doke⁄, taútjn êkdédwka t®n êzßgjsin, eîv tría diairouménjn, Üv e÷rjtai, ˜n

∏kaston eîv ânagnÉseiv dieilómjn e÷toun ömilíav· ên afiv ânagnÉsesin ∂sti mèn proqewría

tiv ên ta⁄v pleístaiv, êpágetai dè ™ toÕ grámmatov diaíresiv genik¬v· e˝ta diaire⁄tai tò

grámma eîdik¬v kaì ërmjneúetai· e˝ta hjtoÕntai tinà ên t¬ç grámmati· e˝ta ºpou de⁄ hjte⁄n

kaì ∂zw toÕ grámmatov ∂nia, oûdè toÕto paríemen. Kaì pròv taÕta tà hjtßmata proxwroÕ-

men t¬ç latinik¬ç trópwç, tiqéntev te tò próbljma kaì êpixeiroÕntev eîv toûnantíon ên to⁄v

pleístoiv· e˝ta diorihómenoi tâljqèv kaì lúontev tà êpixeirßmata· Ω d® t¬n ™metérwn

êzjgjt¬n oûdeív pw méxri t±v ™mérav t±sde, ºsa ge êgÑ o˝da, tugxánei teqarrjkÉv.

18. Bembo’s translation is to be found in the late fifteenth-century manuscript BAV,

Vat. lat. 4560, which also includes an anonymous Latin translation of Psellos’ and Magen-

tenos’ comments on some of the Organon treatises. Cf. JUGIE, Oeuvres complètes de

Gennade Scholarios, vol. VII, p. III, n. 1; EBBESEN-PINBORG, “Gennadios and Western

Scholasticism”, pp. 314-317.

19. Cf. JUGIE, Oeuvres complètes de Gennade Scholarios, vol. VII, p. IV.

20. EBBESEN-PINBORG, “Gennadios and Western Scholasticism”, p. 265.

93690_Hinterberger_13_Ierodiakonou.indd 377 21/03/11 10:30

378 KATERINA IERODIAKONOU

Gennadios’ text is a so-called ‘literal’ commentary, or even three literal

commentaries, one on each of the works, consisting of divisions of

the text commented on into sections and some mini-quaestiones; and

although they do not detect the sources of these literal commentaries,

they think that they also constitute translations from the Latin, judg-

ing from some strange Greek sentences which Gennadios used. Thus,

Ebbesen and Pinborg conclude: “He was, in short, a compilator in

much the same way as Leo Magentenus had been; only his sources

were different”.21 In addition, Ebbesen makes an even stronger state-

ment in one of his more recent articles: “The lection-commentary is

a uniquely Latin phenomenon. The one Greek example I know, viz.

George Scholarios’ commentary on the Ars Vetus, is a translation from

the Latin”.22

But is it really the case that Gennadios’ logical commentaries are

nothing but mere translations from the Latin? It is certainly true that

in his dedicatory letter Gennadios proudly acknowledged the Western

influence on his logical writings. However, he did that only after hav-

ing paid tribute to the Greek commentators whom he clearly consid-

ered to be indispensable teachers for the better understanding and

interpretation of Aristotle’s Organon. Should we, then, insist that

Gennadios slavishly follows Latin sources? To settle this issue, one

would obviously need to study systematically all the passages from

Gennadios’ logical commentaries which do not stem from Brito’s

work and try to find out whether their sources are Greek or Latin.

Here, however, I have chosen to concentrate just on Gennadios’ com-

ments on the De interpretatione; for what immediately struck me is

the fact that this commentary includes, again according to Ebbesen

and Pinborg, translated extracts from Brito’s work only at two places.

In particular, it only includes two clearly marked quaestiones which

together are not more than five and a half pages in length (297.23-

300.31 and 347.7-348.29). So, what about the remaining 105 pages of

Gennadios’ comments on the De interpretatione? What are the sources

on which Gennadios relied here? Are they exclusively Latin sources?

21. EBBESEN-PINBORG, “Gennadios and Western Scholasticism”, p. 267.

22. S. EBBESEN, “Greek and Latin Medieval Logic”, in: Cahiers de l’Institut du Moyen-

Âge Grec et Latin 66 (1996), pp. 67-93, esp. p. 85; reprinted in IDEM, Greek-Latin

Philosophical Interaction (Collected Essays of Sten Ebbesen, 1), Aldershot 2008, pp. 137-

156, at p. 150.

93690_Hinterberger_13_Ierodiakonou.indd 378 21/03/11 10:30

THE WESTERN INFLUENCE 379

In his comments on the De interpretatione Gennadios referred twice

to Boethius (242.6; 293.28), once to Albert the Great (347.29), once

to the Latin scholars in general (250.8), and once to Averroes (337.3).

He never mentioned Thomas Aquinas by name, although John Dem-

etracopoulos has recently undertaken to compile a detailed list of

Gennadios’ comments that constitute translations from Aquinas’

commentary on the De interpretatione.23 Indeed, this list clearly shows

that Gennadios’ comments depend on Aquinas’ work to a great

extent. But even this influence cannot account for the whole of Gen-

nadios’ text; for there are also his explicit references to Greek

sources.

More specifically, apart from the subsidiary allusions to views put

forward by Aspasius (259.27), Alexander (254.37; 259.31; 264.5;

279.15), Porphyry (278.32; 338.30), and the grammarians (250.13;

253.31), allusions which constitute digressions rather than being

strictly relevant to the issues discussed in this particular Aristotelian

treatise, Gennadios seems to have taken into serious consideration two

Greek commentaries when composing his own logical comments,

namely, Ammonius’ commentary on the De interpretatione and

Psellos’ paraphrase of the same work. In fact, Gennadios referred by

name to Ammonius ten times (250.21; 251.12; 255.8; 319.26;

337.33; 338.11; 22; 26; 37; 339.5) and to Psellos twice (266.3;

338.9). And although some of the references to Ammonius are clearly

due to Aquinas (250.21; 251.12; 255.8), there is at least a substantial

passage (337.33-339.6) in which Gennadios engaged himself directly

in a lively dialogue with Ammonius’ comments, expressing a strong

disagreement with him. In particular, the issue discussed here con-

cerns the authenticity of chapter fourteen of the De interpretatione:

after having presented Ammonius’ position that Aristotle is not the

23. I am indebted to John Demetracopoulos for providing me with the list of Schol-

arios’ passages that are translations from Aquinas’ commentary on the De interpretatione.

A brief version of this list will be included in his lemma on Gennadios for the forthcom-

ing Ueberweg volume on Byzantine philosophy, edited by G. KAPRIEV. On Scholarios and

Aquinas, see J.A. DEMETRACOPOULOS, “Georgios Gennadios II - Scholarios’ Florilegium

Thomisticum. His Early Abridgment of Various Chapters and Quaestiones of Thomas

Aquinas’ Summae and His Anti-Plethonism”, in: Recherches de théologie et philosophie

médiévales 69/1 (2002), pp. 117-171, and IDEM, “Georgios Gennadios II - Scholarios’

Florilegium Thomisticum II (De fato) and Its Anti-Plethonic Tenor”, in: Recherches de

théologie et philosophie médiévales 74/2 (2007), pp. 301-376.

93690_Hinterberger_13_Ierodiakonou.indd 379 21/03/11 10:30

380 KATERINA IERODIAKONOU

author of this part of the treatise, Gennadios argued in favour of the

contrary thesis; and it is in the same context that Psellos is also men-

tioned as following the erroneous position held by Ammonius.

Furthermore, there are occasions in his De interpretatione com-

mentary on which Gennadios clearly tried to differentiate his under-

standing of the Aristotelian text from the generally accepted one. In

such cases he first stated the interpretation to which most scholars

adhered, and then offered an alternative interpretation which he

regarded as better and thus favoured it over the others (e.g. 257.16;

283.32; 315.28). So, even if such alternative interpretations should

not always be thought of as Gennadios’ original interpretations, it is

reasonable to think of them as marking his attempt to take a critical

stance towards his sources and to present his own point of view.

But if the content of Gennadios’ commentary on the De interpre-

tatione does not simply follow a Latin source, what about its method?

Is it really the case that the structure of his logical comments repro-

duces that of the Latin commentaries on Aristotle’s Organon? It is

noticeable that at the beginning of most sections of the De interpre-

tatione commentary there are brief informative analyses of the issues

to be discussed in what follows (e.g., 256.4ff.; 260.11ff.; 262.32ff.;

270.12ff.; 282.18ff.; 289.37ff.; 301.6ff.). That is to say, Gennadios’

common practice was first to divide and subdivide the issues to be

discussed and then to focus on certain points and comment on them

in greater detail. But the fact that he did not add in this particular

commentary any quaestiones, apart from the two which he translated

from Brito’s work, as I have already mentioned, makes the structure

of his commentary very similar to that of the Greek commentaries

known as ‘praxis-commentaries’, which were also divided into sec-

tions, the praxeis, and started with an analysis of the argumentation

followed by detailed comments on specific points; such a commen-

tary, for instance, is Stephanus’ commentary on the De interpreta-

tione.24 Hence, it would be pertinent to suggest that the method of

Gennadios’ commentary has as much in common with the method

of some Greek logical commentaries as it does with that of the Latin

ones.

24. Cf. EBBESEN, “Greek and Latin Medieval Logic”, pp. 84-87; IDEM, Greek-Latin

Philosophical Interaction, pp. 150-152.

93690_Hinterberger_13_Ierodiakonou.indd 380 21/03/11 10:30

THE WESTERN INFLUENCE 381

To summarize, if Gennadios stressed in his dedicatory letter the

contribution of Latin scholars to the interpretation of Aristotle’s

logical treatises, it is because the inclusion in his commentaries of

their views constituted a real innovation in the Greek commentary

tradition. Nevertheless, he certainly did not want to imply that he

relied exclusively on Latin sources. For Gennadios, just like any other

Byzantine commentator, made ample use of the ancient Greek com-

mentaries as well as of those produced by previous Byzantine scholars,

and most importantly, he made no claim to originality. On the con-

trary, he presented himself, again in his dedicatory letter, as nothing

but a compilator who added at only a few places his judgement about

which interpretation he regarded as the most convincing (5.26-32);25

and this seems to have been his practice, at least in the case of his De

interpretatione commentary. It should, therefore, be no surprise that

he brought together comments from different authors, exactly like

Magentenos, though Gennadios’ sources were both Greek and Latin.

And it would be an oversimplification to claim that he slavishly

followed a Latin source, an oversimplification which may prevent us

from undertaking the interesting, though I acknowledge quite diffi-

cult, task of inquiring into the reasons that led Gennadios to choose

the different sources he actually did at the different sections of his

commentary.

Gennadios’ decision to make use of both Greek and Latin sources

admittedly constitutes the important difference which distinguishes

him from the other Byzantine commentators, a difference which calls

for some explanation and to which I want to devote some brief final

remarks. For the question which is particularly puzzling with regard

to the Western influence on Gennadios’ logical endeavours is the one

inquiring into the reasons which led a Byzantine scholar for the first

time at the first part of the fifteenth century to take into consideration

Western scholarship. Historians of the period would perhaps invoke

a series of political reasons that urged Gennadios to be open to the

Latin influence, especially such political reasons as those connected

25. ˆEn ôlígoiv mèn oŒn kaì diaforàv doz¬n tíqemen kaì kríseiv perì toútwn ™metérav

kaì gnÉmav îdíav, âll’ ên to⁄v pleíosin êktrepómenoí te kenodozían kaì sofíav dózan Økista

prospoioúmenoi, oΔte toùv ãllouv êlégxein, oΔte aûtoì êpideíknusqai ©ziÉsamen, âll’

©gapßsamen tàv âljqestérav êzjgßseiv dokoúsav e˝nai t¬n êgnwsménwn, taútav tiqénai,

oûdèn prosdiorihómenoi oœ te eîsì kaì ºtou xárin t¬n ãllwn pléon êdokimásqjsan.

93690_Hinterberger_13_Ierodiakonou.indd 381 21/03/11 10:30

382 KATERINA IERODIAKONOU

with the attempts to unify the Churches. In fact, Gennadios attended

in 1438-1439 the Council of Ferrara-Florence, in which he took a

Unionist position, although he soon after turned into an avowed

opponent of the Union of the Churches and became the leader of the

anti-Unionist party.26

This is the historian’s perspective, which by no means excludes the

possibility to understand Gennadios’ interest in and use of the Latin

logical works on the basis of their philosophical merits. In other

words, it is more rewarding, from a philosophical point of view, to

single out the reasons which, according to Gennadios, made it par-

ticularly advantageous to incorporate in his logical commentaries the

scholastic tradition. And it becomes, I think, clear both from his

dedicatory letter and from scattered remarks in his De interpretatione

commentary that he opted for a combination of Latin and Greek

sources because, in this way, both the method and the philosophical

content of his logical comments could be significantly improved.

More specifically, the Latin method contributed to the clarity and

precision of his commentaries, qualities which enhanced their peda-

gogical value and greatly facilitated their teaching. As to the content

of Gennadios’ commentaries, the inclusion of the Latin views offered

a more comprehensive account of the different interpretations of Aris-

totle’s doctrines, and thus guaranteed a better stance from which one

would be able to recognize the best interpretation. But again, even on

the occasions on which Gennadios confessed the importance of Latin

influence, he did not fail to treat the Greek sources with comparable

respect. For instance, when he mentioned in his dedicatory letter his

translation of Aquinas’ commentary on the Posterior Analytics, he also

felt the need to point out that the views of the Greek commentators

should not be neglected, if we want to reach a clear, precise and bet-

ter interpretation of Aristotle’s thought (5.2-12).

So, when Gennadios was composing his logical commentaries, he

seems to have been well aware of the fact that he belonged to a long

commentary tradition. And he treated this commentary tradition as

part of the philosophical output, in the sense that he regarded the

views of the previous commentators as philosophically important. The

26. G. PODSKALSKY, “Die Rezeption der thomistischen Theologie bei Gennadios II.

Scholarios (1403-1472)”, in: Theologie und Philosophie 49 (1974), pp. 305-323.

93690_Hinterberger_13_Ierodiakonou.indd 382 21/03/11 10:30

THE WESTERN INFLUENCE 383

same awareness of the significance and variety of the previous com-

mentary tradition we find in the fourteenth century in the prefatory

remarks of Sophonias’ paraphrasis of Aristotle’s De anima (1.5-2.3).27

The crucial difference in Gennadios’ case, however, is that he con-

sciously added the commentary tradition inaugurated by the Latin and

Arab scholars, parallel to the established ancient and Byzantine tradi-

tion. Moreover, in Gennadios’ case it is interesting to note that,

although the commentator’s task still was, of course, to explain Aris-

totle’s text by offering interpretations of obscure passages, at the same

time the commentator took seriously and commented on the views of

his predecessors, views which were regarded by Gennadios as further

continuing Aristotle’s thought. For in his view, the role of the com-

mentator was not only to transform Aristotle’s thought for pedagogical

purposes, and thus to introduce a literary innovation, but to expand

on it in certain ways. And it makes sense to suggest, I think, that such

a development is closely connected to the fact that Gennadios con-

sciously presented the tradition inaugurated by the Latin scholars.

To conclude, Gennadios seems to have been the only author among

the Byzantine commentators on Aristotle’s logic who was open to the

influence of the scholastic tradition. This influence, however, should

not be seen as having the character of a mere translation or of a slav-

ish dependence on the Western tradition. Gennadios’ commentaries

on the Ars Vetus combine elements from both the Greek and the Latin

logical commentaries in an innovative manner, so that what becomes

intriguing is to examine carefully how the two traditions are brought

together in a coherent whole. Unfortunately, however, there was no

time left for his example to be followed by other Byzantine commen-

tators, who could have thus been able perhaps to breathe new life into

their fast aging commentary tradition. It is not until much later that

someone like Theophilos Korydalleus (1574-1646), who was trained

in Padua at the beginning of the seventeenth century (1609-1613),

could again produce in his works such an amalgam of Western scho-

lasticism and the Greek commentary tradition.28

27. Cf. B. BYDÉN, “Logotexnikév kainotomíev sta prÉima palaiológeia upomnßmata

sto Perí cuxßv tou Aristotélj”, in: Upómnjma 4 (2006), pp. 221-251.

28. Œuvres Philosophiques de Théophile Corydalée, vol. I: Introduction à la Logique,

ed. by A. PAPADOPOULOS and C. NOICA, Bucharest 1970; vol. II: Commentaires à la

Métaphysique, ed. by C. NOICA and T. ILIOPOULOS, Bucharest 1972.

93690_Hinterberger_13_Ierodiakonou.indd 383 21/03/11 10:30

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Comic Terminations in Aristophanes and The Comic FragmentsDocument63 paginiComic Terminations in Aristophanes and The Comic FragmentsAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- The Use and Abuse of Poverty - Aristophanes 'Plutus' 415-610 and The Public Speeches of The Corinthian War PDFDocument26 paginiThe Use and Abuse of Poverty - Aristophanes 'Plutus' 415-610 and The Public Speeches of The Corinthian War PDFAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- The Position of Attic Women in Democratic Athens - Ancient History, Resources For Teachers PDFDocument29 paginiThe Position of Attic Women in Democratic Athens - Ancient History, Resources For Teachers PDFAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- Divine Activity and Human LifeDocument29 paginiDivine Activity and Human LifeAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- This Copy Is For Personal Use Only - Distribution ProhibitedDocument15 paginiThis Copy Is For Personal Use Only - Distribution ProhibitednetvelopxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beliefs, Post-Truth and Politics PDFDocument8 paginiBeliefs, Post-Truth and Politics PDFAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- A Dark Dionysus - The Transformation of A Greek God Between The Bronze and Iron Age PDFDocument23 paginiA Dark Dionysus - The Transformation of A Greek God Between The Bronze and Iron Age PDFAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- Clytemnestra's BreastDocument21 paginiClytemnestra's BreastAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- The Comic Poetics of Apollo in Aristophanes' KnightsDocument19 paginiThe Comic Poetics of Apollo in Aristophanes' KnightsAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- Intratextual Irony in AristophanesDocument26 paginiIntratextual Irony in AristophanesAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- Chapter Eleven Socrates, The Greatest Sophist?: Luiz Paulo RouanetDocument9 paginiChapter Eleven Socrates, The Greatest Sophist?: Luiz Paulo RouanetAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- Aphrodite and Athena in The Lysistrata of Aristophanes PDFDocument11 paginiAphrodite and Athena in The Lysistrata of Aristophanes PDFAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- Code and Performance in Jean GenetDocument286 paginiCode and Performance in Jean GenetAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- Mimesis, Narrative and Subjectivity in The Works of Girard and Ricoeur PDFDocument13 paginiMimesis, Narrative and Subjectivity in The Works of Girard and Ricoeur PDFAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- Combative Capping in Aristophanic Comedy PDFDocument38 paginiCombative Capping in Aristophanic Comedy PDFAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- Virtue Ethics and Democratic ValuesDocument33 paginiVirtue Ethics and Democratic ValuesAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- Behind Bakhtin Russian Formalism and Kri PDFDocument28 paginiBehind Bakhtin Russian Formalism and Kri PDFFatimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apeiron - Kennedy and Stichometry - Some Methodological ConsiderationsDocument23 paginiApeiron - Kennedy and Stichometry - Some Methodological ConsiderationsAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- The Rhetoric of IntertextualityDocument19 paginiThe Rhetoric of IntertextualityAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- Archaeology and History of the Black Sea's Local TribesDocument29 paginiArchaeology and History of the Black Sea's Local TribesAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- A Late Mycenaean Journey From Thera To Naxos - VlachopoulosDocument14 paginiA Late Mycenaean Journey From Thera To Naxos - VlachopoulosAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- Dante 02 Purgatorio PDFDocument250 paginiDante 02 Purgatorio PDFAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- Dante InfernoDocument262 paginiDante InfernoTedd XanthosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Funeral Rites, Queer PoliticsDocument41 paginiFuneral Rites, Queer PoliticsAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- Scapegoat Rituals in Ancient GreeceDocument22 paginiScapegoat Rituals in Ancient GreeceAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- Laughter As-At The Rhetoric of DemocracyDocument27 paginiLaughter As-At The Rhetoric of DemocracyAnonymous OpjcJ3Încă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- UNIMED Past Questions-1Document6 paginiUNIMED Past Questions-1snazzyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Pre-Qualification - Registration of Vendors For Supply of Various Raw Materials - ProductsDocument2 paginiGlobal Pre-Qualification - Registration of Vendors For Supply of Various Raw Materials - Productsjavaidkhan83Încă nu există evaluări

- Maurice Strong by Henry LambDocument9 paginiMaurice Strong by Henry LambHal ShurtleffÎncă nu există evaluări

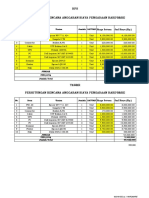

- HPS Perhitungan Rencana Anggaran Biaya Pengadaan Hardware: No. Item Uraian Jumlah SATUANDocument2 paginiHPS Perhitungan Rencana Anggaran Biaya Pengadaan Hardware: No. Item Uraian Jumlah SATUANYanto AstriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rev Transcription Style Guide v3.3Document18 paginiRev Transcription Style Guide v3.3jhjÎncă nu există evaluări

- KARTONAN PRODUkDocument30 paginiKARTONAN PRODUkAde SeprialdiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design Thinking SyllabusDocument6 paginiDesign Thinking Syllabussarbast piroÎncă nu există evaluări

- #1 HR Software in Sudan-Khartoum-Omdurman-Nyala-Port-Sudan - HR System - HR Company - HR SolutionDocument9 pagini#1 HR Software in Sudan-Khartoum-Omdurman-Nyala-Port-Sudan - HR System - HR Company - HR SolutionHishamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exam SE UZDocument2 paginiExam SE UZLovemore kabbyÎncă nu există evaluări

- AL E C Usda S W P: OOK AT THE Ngineering Hallenges OF THE Mall Atershed RogramDocument6 paginiAL E C Usda S W P: OOK AT THE Ngineering Hallenges OF THE Mall Atershed RogramFranciscoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pot PPTDocument35 paginiPot PPTRandom PersonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Republic vs. Maria Lee and IAC, G.R. No. 64818, May 13, 1991 (197 SCRA)Document1 paginăRepublic vs. Maria Lee and IAC, G.R. No. 64818, May 13, 1991 (197 SCRA)PatÎncă nu există evaluări

- CVA: Health Education PlanDocument4 paginiCVA: Health Education Plandanluki100% (3)

- Cambridge IGCSE: 0500/12 First Language EnglishDocument16 paginiCambridge IGCSE: 0500/12 First Language EnglishJonathan ChuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adult Education and Training in Europe 2020 21Document224 paginiAdult Education and Training in Europe 2020 21Măndița BaiasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business Beyond Profit Motivation Role of Employees As Decision-Makers in The Business EnterpriseDocument6 paginiBusiness Beyond Profit Motivation Role of Employees As Decision-Makers in The Business EnterpriseCaladhiel100% (1)

- Bpo Segment by Vitthal BhawarDocument59 paginiBpo Segment by Vitthal Bhawarvbhawar1141100% (1)

- Lec 1 Modified 19 2 04102022 101842amDocument63 paginiLec 1 Modified 19 2 04102022 101842amnimra nazimÎncă nu există evaluări

- What is your greatest strengthDocument14 paginiWhat is your greatest strengthDolce NcubeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scantype NNPC AdvertDocument3 paginiScantype NNPC AdvertAdeshola FunmilayoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mitanoor Sultana: Career ObjectiveDocument2 paginiMitanoor Sultana: Career ObjectiveDebasish DasÎncă nu există evaluări

- 20 Laws by Sabrina Alexis and Eric CharlesDocument58 pagini20 Laws by Sabrina Alexis and Eric CharlesLin Xinhui75% (4)

- Reading and Writing Skills: Quarter 4 - Module 1Document16 paginiReading and Writing Skills: Quarter 4 - Module 1Ericka Marie AlmadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- BAFINAR - Midterm Draft (R) PDFDocument11 paginiBAFINAR - Midterm Draft (R) PDFHazel Iris Caguingin100% (1)

- Shilajit The Panacea For CancerDocument48 paginiShilajit The Panacea For Cancerliving63100% (1)

- 10 1108 - Apjie 02 2023 0027Document17 pagini10 1108 - Apjie 02 2023 0027Aubin DiffoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analyzing Transactions To Start A BusinessDocument22 paginiAnalyzing Transactions To Start A BusinessPaula MabulukÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diaz, Rony V. - at War's End An ElegyDocument6 paginiDiaz, Rony V. - at War's End An ElegyIan Rosales CasocotÎncă nu există evaluări

- General Ethics: The Importance of EthicsDocument2 paginiGeneral Ethics: The Importance of EthicsLegendXÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amazfit Bip 5 Manual enDocument30 paginiAmazfit Bip 5 Manual enJohn WalesÎncă nu există evaluări