Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Case Law

Încărcat de

Raj Chouhan0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

21 vizualizări5 paginicase

Titlu original

case law

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentcase

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

21 vizualizări5 paginiCase Law

Încărcat de

Raj Chouhancase

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 5

MANU/SC/0044/1953

Equivalent Citation: AIR1953SC 476, [1953]24ITR519(SC ), [1954]1SC R195

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA

Civil Appeal No. 161 of 1952

Assessment Year: 1947-1948

Decided On: 08.10.1953

Appellants:Allahabad Bank Ltd.

Vs.

Respondent:Commissioner of Income Tax, West Bengal

Hon'ble Judges/Coram:

M. Patanjali Sastri, C.J., Ghulam Hasan, N.H. Bhagwati, Sudhi Ranjan Das and Vivian

Bose, JJ.

Case Note:

Trust and Societies - disallowance of deduction - Sections 10 (2), 10 (4)

and 66 (1) of Indian Income-tax Act, 1922 and Section 3 of Indian Trusts

Act, 1882 - appeal from the judgment and Order of the High Court on a

reference made by the Income-tax Appellate Tribunal under Section 66(1)

of the Indian Income-tax Act - trust created by bank to provide pension to

its members - payment made to trust - bank deducted it as item of

expenditure - absence of obligation to grant pension to members -

uncertainty regarding beneficiaries - person for whose benefit the

confidence is accepted is beneficiary - no valid trust - held, amount cannot

be allowed as item of expenditure within meaning of Section 10 (2) (15).

JUDGMENT

N.H. Bhagwati, J.

1. This is an appeal from the judgment and order of the High Court of Judicature at

Calcutta on a reference made by the Income-tax Appellate Tribunal under Section

66(1) of the Indian Income-tax Act (XI of 1922).

2. The appellant is a banking company carrying on business at, among other places,

Calcutta and Allahabad. On the 15th March, 1946, the appellant executed a deed by

which it purported to create a trust for the payment of pensions to the members of its

staff. The deed declared that a pension fund had been constituted and established. It

then recited that a sum of Rs. 2,00,000, had already been made over to three persons

who were referred to as the "present trustees" and proceeded to state that the fund

would consist in the first instance of the said sum of Rs. 2,00,000, and that there

would be added to it such further contribution that the bank might make from time to

time, though it would not be bound to make such contributions. In the course of the

accounting year 1946-47, the bank made a further payment of Rs. 2,00,000 to this

fund.

3 . In its assessment for the assessment year 1947-48 the appellant claimed

deduction of that sum of Rs. 2,00,000 under section 10(2)(xv) of the Act on the

ground that it was an item of expenditure laid out or expended wholly and

exclusively for the purposes of its business. The Income-tax Officer, the Appellate

Assistant Commissioner and the Income-tax Appellate Tribunal rejected this claim of

17-07-2019 (Page 1 of 5) www.manupatra.com NATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, BHOPAL

the appellant and the Income-tax Appellate Tribunal at the instance of the appellant

stated a case and referred for the consideration of the High Court the following

question :-

"Whether in the facts and circumstances of this case, the Income-tax

Appellate Tribunal was right in disallowing Rs. 2,00,000 as a deduction

under section 10(2)(xv) of the Indian Income-tax Act."

4. The High Court answered the question in the affirmative and hence this appeal.

5. Though several contentions were sought to be raised by the appellant as well as

the Income-tax authorities before the High Court as arising from the question, the

only contention which was canvassed before the High Court and was held to be

determinative of the inquiry before it was whether the deed of trust dated the 15th

March, 1946, was valid. On the construction of the several provisions of the deed of

trust the High Court held :-

"I am of opinion that in view of these provisions of the trust deed coupled

with the uncertainty as regards the beneficiaries and the absence of any

obligation to grant any pension, no legal and effective trust was created, and

the so-called trust must be held to be void."

6 . It further held that even if the ownership of the money had passed over to the

trustees, still the further provision regarding the application of the money to the

payment of pensions being entirely ineffective and void, the money cannot be said to

have been expended for the purpose of the business, and that therefore was not an

expenditure or an expenditure for the purposes of the business within the meaning of

section 10(2)(xv) of the Act. This was also the only contention urged before us by

Shri N. C. Chatterjee appearing on behalf of the appellant.

7 . Section 3 of the Indian Trusts Act (II of 1882) defines a trust as an obligation

annexed to the ownership of property, and arising out of a confidence respond in and

accepted by the owner, or declared and accepted by him, for the benefit of another,

or of another and the owner. The person for whose benefit the confidence is accepted

is called the "beneficiary". Section 5 in so far as it is material for the purpose of this

appeal says that no trust in relation to movable property is valid unless declared as

aforesaid (i.e., by a non-testamentary instrument in writing singed by the author of

the trust or the trustee and registered, or by the will of the author of the trust or of

the trustee) or unless the ownership of the property is transferred to the trustee.

Section 6 of the Act provides that subject to the provisions of section 5, a trust is

created when the author of the trust indicates with reasonable certainty by any words

or acts......(c) the beneficiary........The validity or otherwise of the trust in question

has got to be determined with reference to the above sections of the Indian Trusts

Act.

8. The deed of trust provided in clause 5 that the income of the fund if sufficient and

if the income of the fund shall not be sufficient then the capital of the fund shall be

applied in paying or if insufficient in contributing towards the payment of such

pensions and in such manner as the bank or such officers thereof as shall be duly

authorised by the bank in that behalf shall direct to be paid out of the fund. Clause 7

stated that the fund was established for the benefit of retiring employees on the

European and Indian staff of the bank to whom pensions shall have been granted by

the bank. Clause 8 provided that any officer on the European staff of the bank who

had been in the service of the bank for at least twenty-five years and any officer or

other employee on the Indian staff of the bank who had been in the service of the

bank for at least thirty years might apply to the bank for a pension, and that in

17-07-2019 (Page 2 of 5) www.manupatra.com NATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, BHOPAL

special circumstances the bank might grant pensions to employees who had not

completed the respective periods of service abovementioned. Clause 9 provided for

the withdrawal, modification or determination by the bank of any pension payable

thereunder when in its opinion the conduct of the recipient or the circumstances of

the case justified it in so doing and the trustees were bound forthwith to act upon

any directions of the bank or of any officers thereof duly authorised by the bank in

that behalf. Clause 11 invested the bank with discretion in fixing the amount of each

pension and in making any modification therein but without prejudice to such

discretion declared what were the pensions which it was contemplating would be

payable to recipients qualified under the provisions of clause 8 of the deed. Clause

18 authorised the bank from time to time by instrument in writing under its common

seal with the assent in writing of the trustees to alter all or any or the regulations

contained in the deed for the time being relating to the fund and make new

regulations to the exclusion of or in addition to all or any of the regulations for the

time being relating to the fund and for the purposes of that clause all the provisions

contained in the deed were deemed to be the regulations in relation to the fund.

9. On a consideration of the provisions of the deed of trust above set out it is clear

that the bank or its officer duly authorised in that behalf were constituted the sole

authorities to determine what pensions and in what manner the same should be paid

out of the income of the fund. The fund was declared to have been established for

the benefit of the retiring employees to whom pensions shall have been granted by

the bank. Officers of the staff who were qualified under clause 8 were declared

entitled to apply to the bank for a pension. But there was nothing in the terms of the

deed which imposed any obligation on the bank or its officers duly authorised in that

behalf to grant any pension to any such applicant. The pension if granted could also

be withdrawn, modified or determined under the directions of the bank or any officer

of the bank duly authorised in that behalf and such directions were binding on the

trustees. The regulations in relations to the fund could also be altered and new

regulations could be made to the exclusion of or in addition to all or any of the

regulations contained in the deed of trust. It was open under the above provisions for

the bank or its officers duly authorised in that behalf to grant no pension at all to any

officer of the staff who made an application to them for a pension and also to

withdraw, modify or determine any pension payable to such officer if in their opinion

the conduct of the recipient or the circumstances of the case should justify them in so

doing. The whole scheme of the deed invested the bank or its officers duly authorised

in that behalf with the sole discretion of granting or of withdrawing, modifying or

determining the pension and it was not at all obligatory on them at any time to grant

any pension or to continue the same for any period whatever. The beneficiaries

therefore could not be said to have been indicated with reasonable certainty. What is

more it could also be validly urged that there being no obligation imposed upon the

trustees no trust in fact was created, even though the moneys had been transferred to

the trustees.

10. Shri N. C. Chatterjee however urged that the power conferred upon the bank or

its officers duly authorised in that behalf was a power in the nature of trust, that

there was a general intention in favour of a class and a particular intention in favour

of individuals of a class to be selected by them and even though the particular

intention failed from the selection not being made the court could carry into effect

the general intention in favour of the class and that therefore the trust was valid. He

relied in support of this contention on Brown v. Higgs (8 Ves. Junior 561; 32 E.R.

473.) and Burrough v. Philcox (5 Mylne & Graig 72; 41 E.R. 299.). The position in

law as it emerges from these authorities is thus summarised by Lewin on Trusts,

Fifteenth Edition, page 324 :-

17-07-2019 (Page 3 of 5) www.manupatra.com NATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, BHOPAL

"Powers, in the sense in which the terms is commonly used, may be

distributed into mere powers, and powers in the nature of a trust. The former

are powers in the proper sense of the word - that is not imperative, but

purely discretionary; powers which the trustee cannot be compelled to

execute, and which, on failure of the trustee, cannot be executed vicariously

by the court. The latter, on the other hand, are not discretionary, but

imperative, have all the nature and substance of a trust, and ought rather, as

Lord Hardwicke observed, to be designated by the name of trusts. 'It is

perfectly clear', said Lord Eldon, 'that where there is a mere power, and that

power is not executed, the court cannot execute it. It is equally clear, that

wherever a trust is created, and the execution of the trust fails by the death

of the trustee or by accident, this court will execute the trust. But there are

not only a mere trust and a mere power, but there is also known to this court

a power which the party to whom it is given is entrusted with and required to

execute; and with regard to that species of power, the court considers it as

partaking so much of the nature and qualities of a trust, that if the person

who has the duty imposed upon him does not discharge it, the court will, to

a certain extent, discharge the duty in his room and place'. Thus, if there is a

power to appoint among certain objects but no gift to those objects and no

gift over in default of appointment, the court implies a trust for or gift to

those objects equally if the power be not exercised. But for the principle to

operate there must be a clear indication that the settler intended the power

to be regarded in the nature of a trust."

11. This position however does not avail the appellant. As already stated there is no

clear indication in the deed of trust that the bank intended the power to be regarded

in the nature of a trust, inasmuch as there was no obligation imposed on the bank or

its officers duly authorised in that behalf to grant any pension to any applicant. There

was no duty to grant any pension at all and the pension, if granted, could be

withdrawn, modified or determined by the bank or its officers duly authorised in that

behalf as therein mentioned. Under the circumstances it could not be said that there

was a power in the nature of a trust which could be exercised by the court if the

donee of the power for some reason or other did not exercise the same. It will be

appropriate at this stage to consider whether any beneficiary claiming to be entitled

to a pension under the terms of the deed could approach the court for the

enforcement of any provision purporting to have been made for his benefit. Even

though he may be qualified under clause 8 to apply for the grant of pension he could

not certainly enforce that provision because there was no obligation imposed at all on

the bank or its officers duly authorised in that behalf to grant any pension to him and

in the absence of any such obligation imposed upon anybody it would be futile to

urge that a valid trust was created in the manner contended on behalf of the

appellant.

12. In our opinion therefore the High Court was right in the conclusion to which it

came that there was uncertainty as regards the beneficiaries and there was an

absence of any obligation to grant any pension with the result that no legal and

effective trust could be said to have been created and further that the provision of Rs.

2,00,000 in the accounting year 1946-47 was not an expenditure or an expenditure

for the purposes of the business within the meaning of section 10(2)(xv) of the

Indian Income-tax Act.

1 3 . In view of the above we do not think it necessary to go into the interesting

questions which were sought to be raised by the appellant, viz., what was the scope

of the reference, and by the respondent, viz., whether the expenditure was a capital

expenditure or revenue expenditure and if the latter whether the deduction could still

17-07-2019 (Page 4 of 5) www.manupatra.com NATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, BHOPAL

not be allowed in view of the provisions of section 10(4)(c) of the Act.

14. The result therefore is that the appellant fails and must be dismissed with costs.

15. Appeal dismissed.

Agent for the appellant : P.K. Mukherjee.

Agent for the respondent : G.H. Rajadhyaksha.

© Manupatra Information Solutions Pvt. Ltd.

17-07-2019 (Page 5 of 5) www.manupatra.com NATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY, BHOPAL

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Mini Outline Securities RegulationDocument11 paginiMini Outline Securities RegulationGang GaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interim Order in The Matter of Nava Diganta Capital Services LimitedDocument14 paginiInterim Order in The Matter of Nava Diganta Capital Services LimitedShyam SunderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dishonour of Cheques in India: A Guide along with Model Drafts of Notices and ComplaintDe la EverandDishonour of Cheques in India: A Guide along with Model Drafts of Notices and ComplaintEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

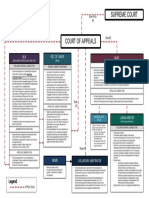

- Labor Dispute Case Flow: Supreme CourtDocument1 paginăLabor Dispute Case Flow: Supreme CourtJacomo CuniitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Export Contract - FinalDocument4 paginiExport Contract - FinalAnonymous GAulxiI100% (1)

- WP 8101 2011 Judgment 06092019Document6 paginiWP 8101 2011 Judgment 06092019Jitendra RavalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rule Ultra Virus by Company14836Document7 paginiRule Ultra Virus by Company14836Sujit KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vimal Chandra Grover Vs Bank of India 26042000 SC0906s000514COM80164Document10 paginiVimal Chandra Grover Vs Bank of India 26042000 SC0906s000514COM80164Rocking MeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business Law CIA 2Document10 paginiBusiness Law CIA 2anushamagaviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contracts Memo PDFDocument8 paginiContracts Memo PDFARSH KAULÎncă nu există evaluări

- DN GhoshDocument9 paginiDN GhoshShreesha Bhat KailankajeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Order in The Matter of M/s Weird Infrastructure Corporation Ltd.Document14 paginiOrder in The Matter of M/s Weird Infrastructure Corporation Ltd.Shyam SunderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interim Order in The Matter of Eris Energy LimitedDocument15 paginiInterim Order in The Matter of Eris Energy LimitedShyam SunderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interim Order - Vikdas Industries LimitedDocument15 paginiInterim Order - Vikdas Industries LimitedShyam SunderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Appropriation of Payments by BanksDocument13 paginiAppropriation of Payments by BanksMALKANI DISHA DEEPAKÎncă nu există evaluări

- Margadarshi Chit Fund CaseDocument21 paginiMargadarshi Chit Fund Casenewguyat77Încă nu există evaluări

- Supreme Court of India Page 1 of 7Document7 paginiSupreme Court of India Page 1 of 7ElampoorananÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amrit Lal Goverdhan Lalan Vs State Bank of Travancs680001COM624260Document7 paginiAmrit Lal Goverdhan Lalan Vs State Bank of Travancs680001COM624260Shuban ShethÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mba 4 TH SemDocument17 paginiMba 4 TH SemAmit SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interim Order - Great Overseas Commodeal LimitedDocument11 paginiInterim Order - Great Overseas Commodeal LimitedShyam SunderÎncă nu există evaluări

- JMM Promotions and Management, Inc. vs. National Labor Relations Commission and Ulpiano L. Delos Santos and Radiola Toshiba Philippines, Inc. vs. The Intermediate Appellate CouDocument4 paginiJMM Promotions and Management, Inc. vs. National Labor Relations Commission and Ulpiano L. Delos Santos and Radiola Toshiba Philippines, Inc. vs. The Intermediate Appellate CouJacinth DelosSantos DelaCernaÎncă nu există evaluări

- LAYA, JR. vs. PHILIPPINE VETERANS BANKDocument5 paginiLAYA, JR. vs. PHILIPPINE VETERANS BANKAlpha ZuluÎncă nu există evaluări

- Main Feature of Deposit Protection BillDocument1 paginăMain Feature of Deposit Protection BillSohel RanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Allahabad High Court - CCS Rules Not Applicable To Professors in UniversityDocument124 paginiAllahabad High Court - CCS Rules Not Applicable To Professors in UniversityvsprajanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supreme Court 11Document31 paginiSupreme Court 11Arjun ThukralÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interim Order in The Matter of Aditya Global Industries LimitedDocument12 paginiInterim Order in The Matter of Aditya Global Industries LimitedShyam SunderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amrit Lal Goverdhan Lalan Vs State Bank of TravancoreDocument9 paginiAmrit Lal Goverdhan Lalan Vs State Bank of TravancoreEbadur RahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interim Order in The Matter of Sarada Pleasure and Adventure LimitedDocument13 paginiInterim Order in The Matter of Sarada Pleasure and Adventure LimitedShyam SunderÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5 Main Processes of CommunicationDocument17 pagini5 Main Processes of CommunicationAashish KohliÎncă nu există evaluări

- SSS Vs COA (433 Phil 946, 11 July 2002)Document2 paginiSSS Vs COA (433 Phil 946, 11 July 2002)Archibald Jose Tiago ManansalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Payment of Gratuity Act ProjectDocument16 paginiPayment of Gratuity Act ProjectRuben RockÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vayam Tech Vs HPDocument7 paginiVayam Tech Vs HPThankamKrishnanÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument8 paginiUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dena Bank Vs C Shivakumar Reddy and Ors 04082021 SC20210508211806011COM440734Document47 paginiDena Bank Vs C Shivakumar Reddy and Ors 04082021 SC20210508211806011COM440734Sravan KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Real Cases in Indian CourtsDocument18 paginiReal Cases in Indian Courtsvikasbembi1864Încă nu există evaluări

- Article 226 Cause of ActionDocument5 paginiArticle 226 Cause of ActionRamakrishnan Harihara IyerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indian Bank Association v. Union of IndiaDocument19 paginiIndian Bank Association v. Union of IndiaBar & BenchÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supreme Court Issues Directions To Change Procedure in Cheque Bounce Cases 2014 SCDocument26 paginiSupreme Court Issues Directions To Change Procedure in Cheque Bounce Cases 2014 SCSridhara babu. N - ಶ್ರೀಧರ ಬಾಬು. ಎನ್100% (1)

- BV Lakshmi v. Geometrix Laser Solutions, para 29Document2 paginiBV Lakshmi v. Geometrix Laser Solutions, para 29Pravesh AgarwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Union Bank of India Vs Rahul Patodi ReplyDocument6 paginiUnion Bank of India Vs Rahul Patodi Replydevansh mishra100% (1)

- The State of Bombay Vs SL Apte and Ors 09121960 Ss600077COM369224Document7 paginiThe State of Bombay Vs SL Apte and Ors 09121960 Ss600077COM369224SunitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MemorialDocument11 paginiMemorialpraokaÎncă nu există evaluări

- FactsDocument5 paginiFactsJustin ManaogÎncă nu există evaluări

- Judgment KusumSharma PDFDocument89 paginiJudgment KusumSharma PDFloveisgood1Încă nu există evaluări

- Equiv Alent Citation: 2016 (3) AC R3108, 2016 (167) AIC 168, AIR2016SC 4363, 2016 (2) ALD (C RL.) 809 (SC), 2016 (97) AC C 487, 2017 (1) ALTDocument6 paginiEquiv Alent Citation: 2016 (3) AC R3108, 2016 (167) AIC 168, AIR2016SC 4363, 2016 (2) ALD (C RL.) 809 (SC), 2016 (97) AC C 487, 2017 (1) ALTMohit JainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nikhil Mehta v. AMR Infrastructure - MatureDocument2 paginiNikhil Mehta v. AMR Infrastructure - MaturePravesh AgarwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pioneer JudgementDocument8 paginiPioneer Judgementkul parashar100% (1)

- G.R. No. 109835 November 22, 1993 JMM Promotions & Management, Inc., Petitioner, National Labor Relations Commission and Ulpiano L. de Los Santos, RespondentDocument3 paginiG.R. No. 109835 November 22, 1993 JMM Promotions & Management, Inc., Petitioner, National Labor Relations Commission and Ulpiano L. de Los Santos, RespondentNapil Dela CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Banking End Sem CasesDocument35 paginiBanking End Sem CasesMahathi BokkasamÎncă nu există evaluări

- LAW 1106 - Statutory Construction - JD 17. G.R. No. 109385 - JMM Promotions vs. NLRC - 11.22.1993 - Full TextDocument3 paginiLAW 1106 - Statutory Construction - JD 17. G.R. No. 109385 - JMM Promotions vs. NLRC - 11.22.1993 - Full TextJOHN KENNETH CONTRERASÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sumitra EviDocument8 paginiSumitra EviBhalla & BhallaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippine International Trading Corporation, Petitioner, - Versus - Commission On Audit, Respondent. G.R. No. 183517Document12 paginiPhilippine International Trading Corporation, Petitioner, - Versus - Commission On Audit, Respondent. G.R. No. 183517Aaron Viloria100% (1)

- Final BSL Ca2Document10 paginiFinal BSL Ca2Rahul PrasadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bank Term Deposit Scheme, 2006Document4 paginiBank Term Deposit Scheme, 2006Sundar RajÎncă nu există evaluări

- Operation MuskaanDocument8 paginiOperation Muskaanaltaibkhan318Încă nu există evaluări

- Interim Order in The Matter of Infocare Infra LimitedDocument14 paginiInterim Order in The Matter of Infocare Infra LimitedShyam SunderÎncă nu există evaluări

- JMM Promotions vs. NLRCDocument4 paginiJMM Promotions vs. NLRCraynald_lopezÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument5 paginiUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- 534 Kotak Mahindra Bank LTD V A Balakrishna 30 May 2022 420033Document22 pagini534 Kotak Mahindra Bank LTD V A Balakrishna 30 May 2022 420033Vidushi RaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Banking Law - Mritunjaya SinghDocument14 paginiBanking Law - Mritunjaya SinghMritunjaya SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bharat Plywood and Timber Vs Employees' Provident Fund On 4 February 1976Document2 paginiBharat Plywood and Timber Vs Employees' Provident Fund On 4 February 1976Shivansh SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsDe la EverandIntroduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Labor Contract Law of the People's Republic of China (2007)De la EverandLabor Contract Law of the People's Republic of China (2007)Încă nu există evaluări

- Advocate of Standing Counsel ListDocument6 paginiAdvocate of Standing Counsel ListRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Practical Workshop IVDocument1 paginăPractical Workshop IVRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Class - IV Computer Practical Windows 10Document2 paginiClass - IV Computer Practical Windows 10Raj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- This Content Downloaded From 106.79.237.34 On Sat, 27 Mar 2021 19:50:14 UTCDocument18 paginiThis Content Downloaded From 106.79.237.34 On Sat, 27 Mar 2021 19:50:14 UTCRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gazette of IndiaDocument2 paginiGazette of IndiaFirstpost100% (2)

- Family Law IDocument16 paginiFamily Law IRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Russia Norway CasseDocument93 paginiRussia Norway CasseRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Constitutional Law II Synopsis VenkateshDocument3 paginiConstitutional Law II Synopsis VenkateshRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Folder - 1 - MP Quiz Marathon - Quiz 1 - 10Document49 paginiFolder - 1 - MP Quiz Marathon - Quiz 1 - 10Raj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- In The Competition Commission of Westeros: 11 Cci Justice Hidayatullah Memorial National Moot Court Competition, 2019Document10 paginiIn The Competition Commission of Westeros: 11 Cci Justice Hidayatullah Memorial National Moot Court Competition, 2019Raj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- BL Has Not Used Its Dominance in The Relevant Market by Leveraging Its Position To Enter Into Another MarketDocument3 paginiBL Has Not Used Its Dominance in The Relevant Market by Leveraging Its Position To Enter Into Another MarketRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Front Page and PrayerDocument8 paginiFinal Front Page and PrayerRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample 1 PDFDocument1 paginăSample 1 PDFRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- IpcDocument1 paginăIpcRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- National Law Institute University, Bhopal: Synopsis Topic: - General Defences and Its LimitationsDocument4 paginiNational Law Institute University, Bhopal: Synopsis Topic: - General Defences and Its LimitationsRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- R Ates For Hiring Auditorium / Lecture Hall of The Convention CentreDocument2 paginiR Ates For Hiring Auditorium / Lecture Hall of The Convention CentreRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Open Justice Vs in Camera Indian Scenario PDFDocument11 paginiOpen Justice Vs in Camera Indian Scenario PDFRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Constitutional Law Semester V SynopsisDocument3 paginiConstitutional Law Semester V SynopsisRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- History II Final PDFDocument28 paginiHistory II Final PDFRaj Chouhan100% (1)

- Finalistcandidates J&KResidentnDocument1 paginăFinalistcandidates J&KResidentnRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 8supreme Court Order - 06-Jun-2018Document2 pagini8supreme Court Order - 06-Jun-2018Raj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- UTDAdmissionsAdvertisement2019 PDFDocument1 paginăUTDAdmissionsAdvertisement2019 PDFRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sem-I Political Science - Major & Minor - PDFDocument2 paginiSem-I Political Science - Major & Minor - PDFRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- General Information About DNLU, JabalpurDocument6 paginiGeneral Information About DNLU, JabalpurRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- President Profile PDFDocument7 paginiPresident Profile PDFSumit kumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exceptions To Articles 15 (1) and 16 (1) .: Annexure IiDocument26 paginiExceptions To Articles 15 (1) and 16 (1) .: Annexure IiKeshav JatwaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nati Onallaw I Nsti Tuteuni Versi Ty Bhopal: Submi T T Edt Odr .Bi Rpalsi NGHDocument4 paginiNati Onallaw I Nsti Tuteuni Versi Ty Bhopal: Submi T T Edt Odr .Bi Rpalsi NGHRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supreme Court of India Page 1 of 99Document99 paginiSupreme Court of India Page 1 of 99Raj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- AdapterCompatibility FinderDocument3 paginiAdapterCompatibility FinderRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Red Zone List April 30 FinalDocument3 paginiRed Zone List April 30 FinalRaj ChouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- USJR - Provrem - Support (2017) EDocument27 paginiUSJR - Provrem - Support (2017) EPeter AllanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Succession - UP BalaneDocument156 paginiSuccession - UP BalaneJeremiah TrinidadÎncă nu există evaluări

- WPM v. LabayenDocument2 paginiWPM v. LabayenVanya Klarika Nuque100% (4)

- Case DigestDocument11 paginiCase DigestAmanda Hernandez0% (1)

- Lyons v. RosenstockDocument2 paginiLyons v. RosenstockToptopÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rectification: LLB 20503 - Law & Equity SEM 1 2021/2022 Murshamshul K MusaDocument17 paginiRectification: LLB 20503 - Law & Equity SEM 1 2021/2022 Murshamshul K MusaSiva NanthaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deutsche Bank No Standing in BK CT TarantolaDocument16 paginiDeutsche Bank No Standing in BK CT Tarantolabsprop7776578Încă nu există evaluări

- Loan Esign CompleteDocument27 paginiLoan Esign CompleteSachin ShastriÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1.SCHMID & OBERLY, INC., Petitioner, vs. RJL MARTINEZ FISHING CORPORATION, Respondent.Document3 pagini1.SCHMID & OBERLY, INC., Petitioner, vs. RJL MARTINEZ FISHING CORPORATION, Respondent.rhodz 88Încă nu există evaluări

- Brown POQDocument4 paginiBrown POQJonas GonzalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- People vs. RTCDocument13 paginiPeople vs. RTCjulieanne07Încă nu există evaluări

- Fact Sheet 02 10 2020 - 0Document2 paginiFact Sheet 02 10 2020 - 0fakey mcaliasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contract Drafting - Assignment 2Document2 paginiContract Drafting - Assignment 2verna_goh_shileiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trusts OutlineDocument8 paginiTrusts OutlineClint Bell100% (1)

- Guidelines1 On Claims ManagementDocument15 paginiGuidelines1 On Claims ManagementDingayegetem DobaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contracts (Forbes) - 2019Document94 paginiContracts (Forbes) - 2019Juliana MirkovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact of Negotiable Instrument Act On Indian EconomyDocument2 paginiImpact of Negotiable Instrument Act On Indian EconomySumanth DÎncă nu există evaluări

- Request For Quotation (RFQ) : Page 1 of 15Document15 paginiRequest For Quotation (RFQ) : Page 1 of 15Nundeep RakshitÎncă nu există evaluări

- This Content Downloaded From 15.206.238.150 On Thu, 22 Jul 2021 06:26:05 UTCDocument24 paginiThis Content Downloaded From 15.206.238.150 On Thu, 22 Jul 2021 06:26:05 UTCaryan sharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agreement: at - Along With Fixtures and Fittings (HereinafterDocument5 paginiAgreement: at - Along With Fixtures and Fittings (HereinafterNikhil PomalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intellectual Property Research PaperDocument5 paginiIntellectual Property Research PaperPraygod ManaseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gardencourt Residences Narra Availability (February 11, 2023)Document1 paginăGardencourt Residences Narra Availability (February 11, 2023)Mia NungaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rent AgreementDocument6 paginiRent AgreementNiket AmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quiroga v. ParsonsDocument2 paginiQuiroga v. ParsonsIvan Luzuriaga100% (2)

- Wisdom Double Manhattan52 PDFDocument1 paginăWisdom Double Manhattan52 PDFGigiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Molo V Molo DigestDocument1 paginăMolo V Molo Digestdivine venturaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hire Purchase AgreementDocument5 paginiHire Purchase AgreementKanhaiya SinghalÎncă nu există evaluări