Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Antiquity

Încărcat de

gemDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Antiquity

Încărcat de

gemDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Antiquity

Sumerian clay tablet, currently housed in the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, inscribed with

the text of the poem Inanna and Ebih by the priestess Enheduanna, the first author whose name is known[6]

When writing systems were created in ancient civilizations, a variety of objects, such as

stone, clay, tree bark, metal sheets, and bones, were used for writing; these are studied

in epigraphy.

Tablet

Main articles: Clay tablet and Wax tablet

See also: Stylus

A tablet is a physically robust writing medium, suitable for casual transport and writing. Clay

tablets were flattened and mostly dry pieces of clay that could be easily carried, and impressed

with a stylus. They were used as a writing medium, especially for writing in cuneiform, throughout

the Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age. Wax tablets were pieces of wood covered in a thick

enough coating of wax to record the impressions of a stylus. They were the normal writing

material in schools, in accounting, and for taking notes. They had the advantage of being

reusable: the wax could be melted, and reformed into a blank.

The custom of binding several wax tablets together (Roman pugillares) is a possible precursor of

modern bound (codex) books.[7] The etymology of the word codex (block of wood) also suggests

that it may have developed from wooden wax tablets.[8]

Scroll

Main article: Scroll

Egyptian papyrus showing the god Osiris and the weighing of the heart.

Scrolls can be made from papyrus, a thick paper-like material made by weaving the stems of the

papyrus plant, then pounding the woven sheet with a hammer-like tool until it is flattened.

Papyrus was used for writing in Ancient Egypt, perhaps as early as the First Dynasty, although

the first evidence is from the account books of King Nefertiti Kakai of the Fifth Dynasty (about

2400 BC).[9] Papyrus sheets were glued together to form a scroll. Tree bark such as lime and

other materials were also used.[10]

According to Herodotus (History 5:58), the Phoenicians brought writing and papyrus to Greece

around the 10th or 9th century BC. The Greek word for papyrus as writing material (biblion) and

book (biblos) come from the Phoenician port town Byblos, through which papyrus was exported

to Greece.[11] From Greek we also derive the word tome (Greek: τόμος), which originally meant a

slice or piece and from there began to denote "a roll of papyrus". Tomus was used by the Latins

with exactly the same meaning as volumen (see also below the explanation by Isidore of Seville).

Whether made from papyrus, parchment, or paper, scrolls were the dominant form of book in the

Hellenistic, Roman, Chinese, Hebrew, and Macedonian cultures. The more modern codex book

format form took over the Roman world by late antiquity, but the scroll format persisted much

longer in Asia.

Codex

A Chinese bamboo book meets the modern definition of Codex

Main article: Codex

Isidore of Seville (d. 636) explained the then-current relation between codex, book and scroll in

his Etymologiae (VI.13): "A codex is composed of many books; a book is of one scroll. It is called

codex by way of metaphor from the trunks (codex) of trees or vines, as if it were a wooden stock,

because it contains in itself a multitude of books, as it were of branches." Modern usage differs.

A codex (in modern usage) is the first information repository that modern people would recognize

as a "book": leaves of uniform size bound in some manner along one edge, and typically held

between two covers made of some more robust material. The first written mention of the codex

as a form of book is from Martial, in his Apophoreta CLXXXIV at the end of the first century, where

he praises its compactness. However, the codex never gained much popularity in the pagan

Hellenistic world, and only within the Christian community did it gain widespread use.[12] This

change happened gradually during the 3rd and 4th centuries, and the reasons for adopting the

codex form of the book are several: the format is more economical, as both sides of the writing

material can be used; and it is portable, searchable, and easy to conceal. A book is much easier

to read, to find a page that you want, and to flip through. A scroll is more awkward to use. The

Christian authors may also have wanted to distinguish their writings from the pagan and Judaic

texts written on scrolls. In addition, some metal books were made, that required smaller pages of

metal, instead of an impossibly long, unbending scroll of metal. A book can also be easily stored

in more compact places, or side by side in a tight library or shelf space.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Wicked Pack of CardsDocument289 paginiA Wicked Pack of CardsBenjamin Hoshour86% (21)

- Standard BOQ TemplateDocument4 paginiStandard BOQ TemplatePirated Soul100% (1)

- 16 S 2220-1356 001 031Document77 pagini16 S 2220-1356 001 031tito del pinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- HTML&Css QuetionDocument11 paginiHTML&Css Quetionmanvi mahipalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clay Tablet Wax Tablet StylusDocument2 paginiClay Tablet Wax Tablet Stylusmansi bavliyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Codices) - in The History of HandDocument20 paginiCodices) - in The History of HandRQL83appÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book 4Document21 paginiBook 4louie gacuanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book 1Document24 paginiBook 1louie gacuanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Etymology: AntiquityDocument7 paginiEtymology: Antiquitynatashadelgado1291Încă nu există evaluări

- Etymology History: The Gutenberg Bible, One of The First Books To Be Printed Using The Printing PressDocument21 paginiEtymology History: The Gutenberg Bible, One of The First Books To Be Printed Using The Printing PressKris KrasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clay Tablet Wax Tablet Stylus: Main Articles: and See AlsoDocument1 paginăClay Tablet Wax Tablet Stylus: Main Articles: and See AlsoAhmed AbdulhakeemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book - WikipediaDocument22 paginiBook - WikipediaAmogh TalpallikarÎncă nu există evaluări

- TopicDocument17 paginiTopicRahadyan NaxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hack Book of KeshabDocument8 paginiHack Book of KeshabKe ShāvÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book - WikipediaDocument22 paginiBook - WikipediaNameÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of BooksDocument5 paginiHistory of BooksRonald GuevarraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book BindingDocument18 paginiBook Bindingiqa_2503Încă nu există evaluări

- Book BindingDocument19 paginiBook BindingZalozba Ignis67% (3)

- Codex: Etymology and Origins History From Scrolls To Codex PreparationDocument8 paginiCodex: Etymology and Origins History From Scrolls To Codex PreparationNirmal BhowmickÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is "Codex"Document8 paginiWhat Is "Codex"magusradislavÎncă nu există evaluări

- Catchwords in Manuscripts and Printed Books: The CodicologyDocument20 paginiCatchwords in Manuscripts and Printed Books: The CodicologyRQL83appÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Scrolls - WikipediaDocument26 paginiHistory of Scrolls - Wikipediajeremiahdung2Încă nu există evaluări

- BookDocument24 paginiBookDiego Alexander Ortiz AsprillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Paper - WikipediaDocument36 paginiHistory of Paper - WikipediaJoshua DaaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scroll - WikipediaDocument4 paginiScroll - WikipediaAmogh TalpallikarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bookbinding BasicsDocument141 paginiBookbinding Basicsasinel100% (11)

- The Origins of The Book by Emily MacMillanDocument21 paginiThe Origins of The Book by Emily MacMillanEmily MacMillanÎncă nu există evaluări

- BookBinding BasicsDocument134 paginiBookBinding Basicsyesnoname70% (23)

- EtymologyDocument2 paginiEtymologyAriel Dela CuevaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abdul Ahad Hannawi - The Role of The Arabs in The Introduction of Paper Into EuropeDocument17 paginiAbdul Ahad Hannawi - The Role of The Arabs in The Introduction of Paper Into EuropeBraulio Roberto Gutiérrez TrejoÎncă nu există evaluări

- PapyrusDocument9 paginiPapyrushasan jamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Paper - WikipediaDocument76 paginiHistory of Paper - WikipediaLKMs HUBÎncă nu există evaluări

- Palæography: Notes upon the History of Writing and the Medieval Art of IlluminationDe la EverandPalæography: Notes upon the History of Writing and the Medieval Art of IlluminationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1Document17 paginiChapter 1SITTI NORHADIJA MOHD ARIFÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of BooksDocument8 paginiHistory of BooksZoraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Etymologiae: Isidore of SevilleDocument1 paginăEtymologiae: Isidore of SevilleAhmed AbdulhakeemÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Invention of Paper: SOURCE: Wisconsin Paper CouncilDocument1 paginăThe Invention of Paper: SOURCE: Wisconsin Paper CounciljeffersonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Material Used For Writing in Ancient TimesDocument7 paginiThe Material Used For Writing in Ancient Timesbusinge innocentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Papyrus Is MadeDocument2 paginiPapyrus Is MadeAJ CyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Museographs: Illuminated Manuscripts: The History Publication of World CultureDe la EverandMuseographs: Illuminated Manuscripts: The History Publication of World CultureEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- 2017 IADE JournalDocument33 pagini2017 IADE Journalab-azzehÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Brief History of Writing Instuments - Ink and LettersDocument2 paginiA Brief History of Writing Instuments - Ink and LettersBijay Prasad UpadhyayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scribe Rubrication Bookbinder: Desk With Chained Books in The ofDocument2 paginiScribe Rubrication Bookbinder: Desk With Chained Books in The ofAhmed AbdulhakeemÎncă nu există evaluări

- E Poster Example For Early PrintingDocument2 paginiE Poster Example For Early Printingapi-243772235Încă nu există evaluări

- Roman Civilizition (CODEX)Document1 paginăRoman Civilizition (CODEX)Norhaina MANGONDAYAÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia For Other Uses, See .: Book (Disambiguation)Document21 paginiFrom Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia For Other Uses, See .: Book (Disambiguation)sujithasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bookrolls As MediaDocument29 paginiBookrolls As MediaWilliam JohnsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chatzopoulou Final PDFDocument6 paginiChatzopoulou Final PDFdevenireÎncă nu există evaluări

- ManuscriptsDocument3 paginiManuscriptsmansi bavliyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Libraries: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocument5 paginiHistory of Libraries: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchRonaldÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Appearance of The BookDocument4 paginiThe Appearance of The BookIoanaLunguÎncă nu există evaluări

- Types of LibrariesDocument11 paginiTypes of Librariessachin1065Încă nu există evaluări

- History of PaperDocument7 paginiHistory of PaperKeanu Menil MoldezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Printed Book (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)De la EverandThe Printed Book (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- Movable Type - WikipediaDocument70 paginiMovable Type - WikipediaLKMs HUBÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pre Industrial AgeDocument28 paginiPre Industrial AgeDaDDy RuThErFoRd0% (1)

- Writing Materials: Writing in The Greco-Roman CivilizationsDocument4 paginiWriting Materials: Writing in The Greco-Roman CivilizationsWolfMensch1216Încă nu există evaluări

- Codex FinalDocument2 paginiCodex FinalNorhaina MANGONDAYAÎncă nu există evaluări

- God’s Word to Us: The Story of How We Got Our BibleDe la EverandGod’s Word to Us: The Story of How We Got Our BibleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Godzilla PowerpointDocument15 paginiGodzilla PowerpointStefano GiacomelliÎncă nu există evaluări

- 120542A Manual Instalación Antenas HDTF - Es PDFDocument2 pagini120542A Manual Instalación Antenas HDTF - Es PDFCarloMagnoCurtisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Service ManualDocument87 paginiService ManualvimannÎncă nu există evaluări

- 'Poetry Is Not A Luxury' by Audre Lorde - On BeingDocument4 pagini'Poetry Is Not A Luxury' by Audre Lorde - On BeingIan Andrés Barragán100% (1)

- TAB Liveloud - No One Like YouDocument2 paginiTAB Liveloud - No One Like YouClarkFedele27100% (1)

- How To Build A Network Intrusion Detection System: Step by Step InstructionsDocument35 paginiHow To Build A Network Intrusion Detection System: Step by Step InstructionsMuh SoimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Long Quiz 4thDocument1 paginăLong Quiz 4thJhay Mhar AÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design Like You Give A Damn ReviewDocument4 paginiDesign Like You Give A Damn ReviewTânia Fernandes0% (1)

- King Porter Stomp GoodmanDocument24 paginiKing Porter Stomp GoodmanRenaud Perrais100% (2)

- Production Weekly - Issue 1096 - Thursday, June 7, 2018 / 150 Listings - 34 PagesDocument1 paginăProduction Weekly - Issue 1096 - Thursday, June 7, 2018 / 150 Listings - 34 PagesProduction WeeklyÎncă nu există evaluări

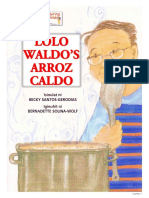

- Lolo Waldo S ArrozcaldoDocument25 paginiLolo Waldo S ArrozcaldoLyn Romero81% (16)

- Egyptian Art ReportDocument44 paginiEgyptian Art ReportSam Sam100% (1)

- I. Directions: Choose and Write The Letter of The Correct Answer. (Strictly No Erasures)Document2 paginiI. Directions: Choose and Write The Letter of The Correct Answer. (Strictly No Erasures)larahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Satipatthana VipassanaDocument50 paginiSatipatthana VipassanapeperetruÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ophs 56 enDocument20 paginiOphs 56 enCarlos RuizÎncă nu există evaluări

- Regent BrochureDocument81 paginiRegent BrochurekasunÎncă nu există evaluări

- Informative SpeechDocument3 paginiInformative SpeechNorman Laxamana SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Music For Theatre2Document16 paginiMusic For Theatre2OT MusicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Meritor Reman Caliper Catalogue - Web - 1Document234 paginiMeritor Reman Caliper Catalogue - Web - 1SERVICIO AUTOMOTRIZÎncă nu există evaluări

- A. Bonifacio Integrated School Supplemental Activities in Science 7 Second Quarter Week 1Document3 paginiA. Bonifacio Integrated School Supplemental Activities in Science 7 Second Quarter Week 1Rose Ann ChavezÎncă nu există evaluări

- IdkDocument4 paginiIdkvishnu priyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Le Corbusier - SummaryDocument4 paginiLe Corbusier - SummaryBetoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Narasimha PrayersDocument3 paginiNarasimha Prayersgift108Încă nu există evaluări

- The Hidden Symmetry of The Coulomb Problem in Relativistic Quantum Mechanics - From Pauli To Dirac (2006)Document5 paginiThe Hidden Symmetry of The Coulomb Problem in Relativistic Quantum Mechanics - From Pauli To Dirac (2006)Rivera ValdezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dragonlance For Genesys RPGDocument26 paginiDragonlance For Genesys RPGscottwelchkinÎncă nu există evaluări

- World Travel Agency: GermanyDocument8 paginiWorld Travel Agency: GermanyAnonymous 27EhWKmhsaÎncă nu există evaluări