Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Killias Corruption Protocol PDF

Încărcat de

SkL27015Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Killias Corruption Protocol PDF

Încărcat de

SkL27015Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Protocol:

Administrative Reforms in the Public Sector

and their Impact on the level of Corruption: A

Systematic Review

Martin Killias, Giulia Mugellini, Giang Ly Isenring, Patrice

Villettaz

Submitted to the Coordinating Group of:

Crime and Justice

Education

Disability

International Development

Nutrition

Social Welfare

Other:

Plans to co-register:

No

Yes Cochrane Other

Maybe

Date Submitted:

Date Revision Submitted:

Approval Date:

Publication Date: 04 January 2016

1 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

(1) BACKGROUND

1.1. The Problem, Condition or Issue

Corruption is a pervasive phenomenon and significant in both developed and developing

countries. As a complex social phenomenon, corruption deploys its characteristics under

various and extensive forms which make the definition of corruption particularly complex and

vast.

Literature on the definition of corruption is broad. The following paragraphs will provide the

readers with some commonly used definitions of corruption. However, this overview of

definitions is not intended to be comprehensive. As far as this systematic review will focus on

the administrative corruption, the readers will find below the major features of this form

of corruption rather than other types of corruption.

Corruption is commonly defined as the abuse or misuse of public office (by elected politician

or appointed civil servant) for private gain (Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development OECD 2008: 22; The World Bank 1997: 8; United Nations Office on Drugs and

Crime UNODC 1999). The main offences constituting corrupt behaviour are bribery 1 ,

patronage and nepotism, theft of state assets or diversion of state revenues2, extortion (World

Bank, 1997). Corrupt behaviours are also identified as acts of bribery of domestic or foreign

public officials, trading in influence, embezzlement, misappropriation or other diversion of

property by a public official (OECD 2008: 23; OECD 2015: 28). To widen the notion of

corruption to individuals or private parties, we could also state that corruption is the misuse

of entrusted power for private gain.

Besides the specific types of offences characterizing corrupt behaviours, there is also the

distinction between “petty” and “grand” corruption. This distinction is focused on the

seriousness of the offence, on the amount of money involved and on the hierarchical level of

the public officials concerned. Indeed, “grand” corruption usually involves substantial

amounts of money and high-level public officials and politicians, while “petty” corruption

usually concerns smaller sums of money and typically more junior officials, civil servants

(UNODC 1999; The World Bank 1997; The World Bank 2003).

1“Public office is abused for private gain when an official accepts, solicits, or extorts a bribe. It is also abused

when private agents actively offer bribes to circumvent public policies and processes for competitive advantage

and profit” (The World Bank 1997: 8)

2“Public office can also be abused for personal benefit even if no bribery occurs, through patronage and

nepotism, the theft of state assets, or the diversion of state revenues.” (The World Bank 1997: 8-9)

2 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

Another distinction commonly mentioned in the literature is the one between public and

private corruption. As its name indicates, public corruption concerns the misuse of public

office for private gain while private corruption happens between individuals operating in the

private sector (World Bank 2003: 3).

A third distinction is often made between administrative and political corruption (Khan 2004;

Pope 2000; Riccardi & Sarno 2013). This distinction is more related to the types of

operations/processes influenced by the corrupt behaviour and to the types of public officials

involved. Administrative corruption refers to the state administration at central and local level

(OECD 2015: 19) and involves civil servants. It mainly alters the implementation of policies

(rather than their formulation) and service delivery (Gould 1991; Huberts 1998: 211; OECD

2015: 29; Riccardi & Sarno 2013). Political corruption refers to act at the political level, often

with high-level civil servants involved. It influences the formulation of laws, regulations and

policies and concerns elected public officials (Kramer 1997; OECD 2015: 28; The World Bank

2003: 6).

The categories mentioned above are not mutual exclusive and their meaning often overlaps.

For example, the difference between “grand” and “petty” corruption is often related to the

difference between “political” and “administrative” corruption (Blundo & al. 2006).

Administrative corruption: the problem of this review

The problem this review will address is administrative corruption in the public sector.

This systematic review will refer to the administrative corruption in the public sector as the

abuse of public office or public role for private gain at the implementation end of public

policies or procedures. By public office, we refer to people belonging to any kind of public

institutions (e.g. schools, hospitals) in addition to governmental ones, with the exclusion of

politicians.

This review will consider the following main corrupt acts: bribery of public officials;

embezzlement; misappropriation or other diversion of property by a public official (theft of

state assets or diversion of state revenues), nepotism, as well as a range of corrupt behaviors

such as trading in influence, abuse of function, illicit enrichment. Some corruption-related

concepts will also be included in the review such as fraud and extortion. Fraud is a broader

legal and popular term that covers both bribery and embezzlement. Extortion is a form of

corruption often seen in cases when state officials return preferential business opportunities

and freedom from taxation. According to OECD (2011), asking for a bribe becomes extortion

“when this demand is accompanied by threats that endanger the personal integrity or the life

of the private actors involved."

3 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

Furthermore, absenteeism as a serious form of corruption in specific sectors, such as

education and health (Transparency International 2013) will also be included in this review.

Indeed, “stealing time” (e.g. not show up to work) while performing a public office is

considered a serious form of diversion or theft of state assets (time in this case) (Hanna 2011:

8).

Although administrative corruption is often defined and studied together and as opposed to

political corruption, this systematic review will exclude political corruption. We deliberately

separate politics from administration. Political corruption affects the formulation of policies,

it involves political decision-makers and happens when politicians who are entitled to make

the laws (the rulers) are themselves corrupt. In political corruption, laws and regulations are

abused and even tailored to fit the interest of the rulers. Political corruption takes place at the

high levels of the political system and it has political repercussions (Amundsen, 1999).

Administrative corruption occurs at any level of authority in the public administration and

affects the implementation of policies. The review will not examine the acts of political

corruption mainly because we believe that the mechanisms and the functioning of political

corruption (i.e. manipulations of rules of voting systems) are significantly different and more

complex that those related to administrative corruption. We thus believe that political

corruption would need an ad-hoc separate review.

Anti-corruption interventions/reforms implemented at the administrative

level: the scope of this review

The aim of this systematic review is to identify the impact of the existing interventions or

reforms implemented at the administrative level in order to curb the types of

administrative corruption mentioned above.

The majority of administrative interventions and reforms in the public sector have been

developed to curb public corruption at the state administration level (World Bank 1997,

USAID 2009: 4, European Commission 2014b). Several anti-corruption programs have been,

indeed, developed both at the domestic and international level. In the words of Gounev (2012)

“significant funds are being allocated by the EU cohesion policy to the strengthening of

administrative capacity at all levels, including regionally, especially in less developed

regions and newer EU Member States. The added administrative efficiency that should result

will reduce actual levels of corruption and consequently the pressure on personnel to become

corrupt. Once administrative efficiency has been improved, additional specific anti-

corruption measures can be added.”

The issue so far has been that, in spite of the large amount of anti-corruption programs

implemented (cfr. European Commission 2014b), the literature bringing them into line is most

of the times an overview and compilations of general findings, leading to conclusions which

4 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

might be too general and vague to inspire policy-makers. In addition, evaluations are more

easily available on outcomes of higher sanctions and intensified controls, than on

administrative reforms which try to reduce the “market” for corruption by making public

bureaucracies more efficient and “user-friendly”. Though there has been a noticeable trend of

developing significant anti-corruption programs helping to understand the causes and capture

the indicators of corruption, there has been little systematic research into the impact of these

anti-corruption efforts in reducing corruption. As a consequence, there has been a serious lack

of comprehensive assessment of the implementation and the efficiency of anti-corruption

measures in different settings.

Given the need for such evaluation, we propose a systematic review of all studies that have

examined administrative anti-corruption reforms as well as their effects on the level of

corruption. As formulated by Johnsøn & Søreide (2013: 1), “producing evidence that anti-

corruption interventions have an impact in reducing corruption is a relatively new area for

research and evaluation”. This is the contribution this systematic review is aiming at.

Why the focus on administrative corruption and why it is a target for

administrative anti-corruption interventions/reforms?

In order to keep the systematic review manageable, it only covers administrative corruption.

Along with this primary reason, the focus on administrative corruption and the administrative

anti-corruption reforms is explained as follows:

(1) The importance of the parties involved in administrative corruption

The reason we focus on the public sector corruption is that the state plays a decisive role

and it is reflected in most definitions of corruption. Nevertheless, administrative

corruption also exists within and between private businesses, within non-governmental

organizations, and between individuals in their personal dealings. However, for this

review, when the act of corruption does not imply or emphasize a state-relationship, it will

be excluded from the review. The term “public sector” used for the review does not exclude

the private sector or private companies which might be equally corruptible with serious

public flow-on effect. For this review, we take into consideration the

counterparts/protagonists to the corrupt officials who can be any non-governmental, non-

public individual, or the general public. In sum, acts of corruption with no state

components or public office involvements will be excluded from the review.

This leads us to another significant reason to focus on administration corruption. As a

matter of fact, whenever administrative corruption happens, it does involve numerous

protagonists of the society, namely bureaucratic elites, public officials and interested

individuals or parties. Administrative corruption involves appointed bureaucrats and

public administration staff at the central or subnational levels. As advanced by Johnston

5 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

(2011), administrative corruption implies that within public bureaucracies, abuse of roles,

powers or resources have been found and it has been initiated by staff officials, their

superiors or the agency clients. Although anchored in large and centralized governments,

protagonists of administrative corruption might also be individuals or institutions from

elsewhere in the public sector (Johnston, 2011).

(2) The diversity of types of acts/offences of administrative corruption

The second reason of this focus is mostly related to the vast selection of malfeasant acts

and behaviors emanated from administrative corruption.

The most common act of administrative corruption is, according to Taslim (1994),

pecuniary bribes. However, bribes are not the only forms of administrative corruption. In

a study of Gounev (2012), administrative corruption consists of acts of manipulation of

public tenders, kickbacks from providers, nepotism-based recruitment and promotions.

In the interaction with private agents, administrative corrupt acts can be seen in the

requests of extra payment or speed money for providing government services or to

expedite some bureaucratic procedures. Bribes violating rules and regulations, bribes or

kickbacks in order to obtain positions or to secure promotions, or mutual exchanges of

favors within the public bureaucracy can also be part of administrative corrupt behaviors

(Fjeldstad & Isaksen, 2008: pp. 5-6).

When small payments are involved, administrative corrupt acts can be assimilated to petty

corruption although in some specific cases and in aggregate the sums may become

significant (Blundo & al. 2006).

It also happens that, in order to provide advantages to either state or non-state actors, an

intentional imposition of distortions in the prescribed implementation of existing laws,

rules and regulations has been deployed. For instance an administrative corrupt act

includes bribes to an official inspector to overlook minor (or possibly major) offences of

existing regulations, or bribes to gain licenses, to smooth customs procedures, or to win

public procurement contracts (World Bank, 2000).

Administrative corrupt acts also include the actions of “offering”, “promising” and a bribe

and not only the act of “giving” a bribe. However, our review will consider only the act of

“giving of a bribe”, which occurs when the briber actually transfers the undue advantage

and implies an agreement between the briber and the official. As offering and promising

bribes have not been established as complete offences (OECD 2008, p. 26), we have

decided to exclude these acts from this review.

6 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

1.2. Why it is Important to do the Review

Considering that “the absence of rules facilitates the process of corruption as much as the

presence of cumbersome or excessive rules does” (Bank's General Counsel, Ibrahim Shihata),

an evaluation of what works and what does not is of extreme importance to identify the most

parsimonious and effective “model” to curb corruption issues.

Despite a large amount of literature on anti-corruption, there are few systematic reviews

focusing on anti-corruption reforms and even fewer assessing the issues of effectiveness and

impact. There is thus a need for more comprehensive assessments of the implementation and

the efficiency of anti-corruption measures in different settings.

Therefore, the main objective of this review is to systematically identify any evidence and

evaluation of the effectiveness of different anti-corruption reforms at the administrative level.

Anti-corruption policies or interventions cannot operate successfully without a concrete

assessment of their impact on the level of corruption. Determining the effects of anti-

corruption interventions is integral to the success of the eradication of corruption. It is

necessary to know exactly what has worked, what has been useful so far, what has not worked

and how to do better in the fight against corruption. Consequently, there are not many ways

to acquire such knowledge except from conducting a systematic review of anti-corruption

measures and their effectiveness.

Our systematic review will allow identifying studies presenting anti-corruption reforms and

interventions and comprehensive assessing the outcomes of these interventions.

The proposed research has a main impact for the criminological and criminal law field, but

furthermore, as the subject of corruption and anti-corruption policies and reforms crosses

many other disciplinary boundaries, it also constitutes an opportunity to consider all studies

belonging to different disciplines such as political sciences, economic, business management,

etc. In addition, our review will allow learning where empirical studies are concentrated (for

instance what kinds of interventions and outcomes). Finally, given the lack of assessments of

this sort at the international level, such review will be of high relevance to the international

literature on the theme of administrative anti-corruption strategies.

One major contribution to the subject is the systematic review of Hanna & al. (2011) on “The

effectiveness of anti-corruption policy”. This review demonstrates that the major shortcoming

of existing research on the effectiveness of anti-corruption measures is related to the fact that

they mainly focus on the incentives and advantages of not engaging in corrupt practices, but

there remains a dearth of knowledge in relation to the assessment of administrative reforms

adopted to reduce the “need” (or the “market”) for corrupt behavior.

7 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

The review of Hanna focuses on developing countries, on two main types of interventions (i.e.

monitoring and incentives mechanism, and changing the rules of the system) and it uses a

textual narrative synthesis approach. Hanna stated that there would have been the need to

better understand the long-term effects of anti-corruption strategies focused on the changes

of the rules and on those more oriented to monitoring and incentives interventions (Hanna

2011: 1).

Our review will differentiate from the Hanna’s one by (1) considering both developing and

developed countries (classified in low, middle and high income countries according to the

World Bank and OECD definitions), (2) including a wider range of interventions and not only

“monitoring and incentives programs” or “interventions changing the underlying rules of the

system”, (3) focusing on both micro and macro level studies and (4) by using meta-analysis

instead of textual narrative review. Moreover, this review aims at raising the attention on the

importance of conducting cost-benefit analysis to evaluate interventions (Hanna 2011: 6). This

method has long provided useful policy guidance in many sectors but it is still rarely applied

to the evaluation of anti-corruption interventions (Johnson 2014: 1). Through the

identification and analysis of studies based on this method, this review can help to promoting

its appropriate and informed use.

As far as the features and mechanism for corruption change quickly, as well as the measures

for countering this issue, this systematic review will also serve as an update to the results of

the previous studies.

To conclude, this proposal seeks to answer to the key question: “What is the impact of

administrative interventions and reforms undertaken in the public sector on the

level of administrative corruption, across developed and developing countries?”

We expect to discover through this systematic review which administrative

measures/policies/reforms in the public sector are potentially significant for fighting

corruption, and which ones could be an issue. By compiling and studying the effects of the

anti-corruption interventions in different contexts, we aim to identify which interventions

work and which do not work in the fight against corruption.

8 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

1.3. The Intervention

This systematic review focuses on interventions which represent different types of

administrative reforms mainly focused on curbing corruption.

Administrative reforms have been defined as changes or transformations

developed at the state administration at central and local level under a

systematized and well-directed process. Reform is change or adjustment that is well-

studied and planned with a clear objective of improving the current state of the elements part

of a system (Caiden 1969).

Existing classifications of potential administrative anti-corruption reforms are usually focused

on the schools of thought underneath them, on the types of system used to implement them,

on the process/area they are addressed to.

For example, McCusker (2006) emphasizes three key schools of thought on corruption

prevention and strategies:

(1) Interventionism – the relevant authorities wait for the corrupt action to take place and then

intervene to capture and punish the wrongdoer. This school of thought embodies principles of

retribution, rehabilitation and deterrence. However, it overlooks several problems: the harm

has already occurred and cannot be undone; the majority of corruption cases are unreported;

and no attention is paid to improving supervision to deter corrupt actions in the first place.

(2) Managerialism – the individuals or agencies seeking to engage in corrupt behavior can be

prevented from doing so by establishing appropriate systems, procedures and protocols.

Managerialism advocates the reduction or suppression of opportunities benefiting the

individuals engaging in corruption. However, the limitation of this school resides in the fact

that individuals do not necessarily operate according to the predetermined principles of

managerialism. This often leads to inflation of rules and elimination of discretion that prevents

practical, common-sense solutions.

(3) Organizational integrity – a norm of ethical behavior related to corruption control strategies

and ethical standards needs to be created within an organization’s operational system. This

school supposes that the mechanism of corrupt behavior and deviance stems from the

organization rather than the individuals. Therefore, in order to reach a successful level of

reducing corruption, targeting the organizational context in which individuals operate is

necessary.

Caiden (1969) categorizes the administrative reforms into four types (1) reforms imposed

through political changes, (2) reforms to remedy organizational rigidity, (3) reforms through

the legal system and (4) reforms through changes in attitude.

9 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

Even though there is a degree of disparity between the desire to eliminate corruption and the

delivery of anti-corruption strategies, there are a number of important pragmatic and

innovative mechanisms in anti-corruption efforts. Anti-corruption strategies should be

developed in a way that incorporates policies in relation to the areas and sectors vulnerable to

corruption.

With this regards, Huberts (1998) has distinguished six main anti-corruption strategies:

(1) economic – focused on the reduction of financial and economic stimuli for corruption

(e.g. paying higher salaries to civil servants to reduce vulnerability or temptation to

bribes);

(2) educational – focused on the change of attitudes and values of the population and civil

servants (e.g. through training and educational campaigns; increasing public

exposure; changing family attitudes population; influencing attitude of public

servants; etc.);

(3) cultural – focused on the improvement of the ethical standards and examples given by

management and on the development of ethical code of conduct for civil servants, as

well as on the enhancement of protection for whistle blowers;

(4) organizational or bureaucratic – focused on the improvement of internal control

systems and supervision (e.g. auditing systems), decentralization, selection of

personnel and rotation of personnel; but also technological improvement helping the

organizational system (e.g. conditional cash transfer (CCT) programs), which can help

reducing the possibility for corruption to happen.

(5) political – focused on the improvement of the example given by politicians (e.g. more

commitment by politicians to combat corruption), on an increased transparency in the

monitoring of party finances and on a more rigorous separation of public powers (these

last two examples are not included in this review);

(6) judicial or repressive measures – focused on the implementation of harsher penalties

for corrupt practices but also on the creation of independent anti-corruption agencies.

Huberts’ (1998) classification is more focused on the specific content and characteristics of

different anti-corruption reforms rather than on the school of thought underneath them (such

as McCusker’s classification) or on the system used to develop them (such as Caiden’s

classification). Moreover, Huberts’ classification is based on the views of 257 experts from 49

countries with very different political, economic and societal conditions. Due to its

international orientation and to its more practical implications, Huberts’ classification of anti-

corruption reforms better serves the purpose of this review.

10 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

Six main types of anti-corruption reforms will, therefore, be considered for the purposes of

this review: (1) economic; (2) educational; (3) cultural; (4) organization or bureaucratic; (5)

political; (6) judicial or repressive measures.

Some examples are provided in the following chapter.

Examples of the types of possible interventions

Many important organizations and actors are behind the administrative anti-corruption

reforms. Interventions seeking to reduce the discretionary power and monopoly of the power

by the government officials, improvement of law enforcement, civil service reform, increase of

transparency and improvement of citizen participation (UNDP, 1997). A genuine reform of

bureaucracy by reducing the incentives and opportunities of corruption is one of the anti-

corruption interventions proposed by UNDP.

Efforts and reforms of anti-corruption are deployed in all sectors of education, environment,

energy, health, information technology and transport (USAID, 2011). In 2007, for instance, a

program called “program of collective action” comprising the directions and principles to

counter corruption was developed by OECD.

One of the anti-corruption reforms suggested by Schleifer and Vishny (1993; 610) is to produce

competition between bureaucrats in the provision of government goods, which will drive

bribes down to zero. This arrangement has been introduced in many agencies of the US

government, in particular the passport office. It seems that creating competition in the

provision of government goods might increase theft from the government but at the same time

reduces bribes.

Decentralization is another example of anti-corruption reforms. When applying a

decentralization policy, the responsibility for the implementation of a given policy passes from

a higher level of government to a lower one (Hanna 2011: 9).

The use of technology and electronic payments can help to bypass various lengthy bureaucratic

procedures and to avoid direct contact with civil servants. This can reduce the opportunity for

bribes (Hanna 2011).

In the case of Italy, the new anticorruption law ratified in November 2012 was specifically

addressed to the reduction of administrative corruption through the increase of transparency

and dissemination of information by public administration. Within the three-year national

anti-corruption and integrity action plan addressed to all administration bodies, the following

main areas of administrative anti-corruption reforms have been considered for intervention:

1. Reduce the likelihood of corruption

11 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

2. Increase the detection of corruption cases

3. Create a corruption-proofed environment

The following are some examples of practical interventions which have been developed within

each of these areas:

1. Public e-Procurement to manage public bid processes online and increase

transparency (e.g. Acquistiinretepa.it) and shifts of management staff.

2. Whistleblowers’ protection through the development of informatics systems within

public administration for reporting any suspected operation online. This provision is

applicable to government employees who report misbehaviors under the condition that

they do not commit libel of defamation or infringe on anybody’s privacy (European

Commission 2014a, p. 4). The identity of whistleblowers cannot be disclosed without

their consent.

3. Code of ethics for the public administration (European Commission 2014a, p. 9).

The types of interventions vary also on the basis of the country where they are developed. For

example, Public Expenditure Tracking Surveys (PETS) are considered among the few

methods having a positive impact on corruption in service delivery in developing countries

with a weak system of governance (Sundet 2007, p. 2). The application of PETS in Uganda, for

example, shows that the flow of funds improved dramatically, from 13 percent on average

reaching schools in 1991-95 to around 80 percent in early 2001 (Reinikka and Svensson 2003).

However, this method was not successful in other countries with similar characteristics (e.g.

in Tanzania) (Sundet 2007).

12 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

1.4. How the Intervention Might Work

According to Johnsøn and Søreide (2013: 1-2), even if in the last two decades a substantial

amount of empirical work has been done in order to understand the effects of anti-corruption

interventions in different countries, “producing evidence that these interventions had any

impact in reducing corruption is still a relatively new area for research and evaluation”. Anti-

corruption practitioners are, indeed, still trying to understand how to best translate principles

such as sanctions, control, transparency, and accountability into reforms and programs

against corruption (Ibidem).

In this sense, our study offers a review as a bridge between theory and literature of anti-

corruption strategies/reforms on the one hand and their empirical effectiveness on the other.

The universe of anti-corruption interventions and reforms is vast (see section 1.3 of this

protocol) and, depending on the types of strategy and approach and on the type of actors

involved and the environment where they have been developed, these interventions might

work in different ways.

As mentioned above, as far as a standardized approach in this regard is still missing, the

identification and description of how the different anti-corruption interventions might work,

is among the main aims of our study and will be carefully analyzed during the development of

this review.

However, a preliminary and general approach, based on the anti-corruption interventions’

classification used in our study (see Huberts 1998 and McCusker 2006), can be described as

follows (see Fig.1 below).

13 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

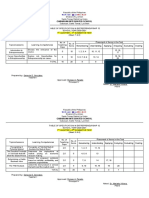

Fig. 1 – Example of the practical functioning of anti-

corruption interventions in the administrative field.

• Administrative corruption (e.g. weak

Problem and unefficient public service delivery

due to corruption among civil

servants/public officials)

• Economic (e.g. higher salaries to civil servants/public officials)

• Educational (e.g. specific anti-corruption trainings)

• Public culture (e.g. code of ethics for civil servants/public officials)

Interventions • Organisational/bureaucratic (e.g. rotation of personnel, internal control and supervision,

stronger selection of public personnel)

• Political (e.g. Good example given by management at the top)

• Repressive/Judicial (e.g. more severe penal sanctions)

• Civil servants earn more

• Civil servants are more trained on

how to recognize and face

Output corruption

• Civil servants are more aware

about the risks of corrupt

behaviours

• More qualified staff

• More efficient public service delivery

Outcome • Less advantages from corruption

• More risks from corruption

• Reduced level of administrative

corruption

Impact • Increased citizens satisfaction

towards public services 'delivery

14 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

A more detailed and illustrative example of how a specific anti-corruption reform might work

is provided by Johnsøn and Søreide (2013: 6) (see figure 2 below).

Fig. 2 – Example of the practical functioning of anti-corruption interventions. Source:

Johnsøn and Søreide (2013: 6)

The authors focus on the process of a program aimed at reducing corruption in customs by

offering a reward to businesses who report they have paid a bribe. For each step of the process,

specific measurable indicators are also provided to show how the impact of this intervention

might be empirically measured. However, Johnsøn and Søreide (2013) also highlight that it is

not always easy to identify and evaluate the working process of a specific intervention, as it

might be difficult to recognize preconditions and intervening variables. The idea is, therefore,

to go beyond the log-frame approach and to also consider the socioeconomic and political

context for the intervention in order to understand how it worked, and thus properly assess

its effects. This is how our study is going to proceed.

15 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

(2) OBJECTIVES

This systematic review aims to identify and synthetize published and unpublished studies

providing empirical evidence on the effects of administrative reforms, developed in the public

sector, to counter administrative corruption.

The main objectives of this systematic review are the following:

1. To identify which types of reforms (or interventions) have a deterrent effect on the level

of administrative corruption across developing and developed countries and to

measure the effectiveness of these reforms.

2. To examine whether different types of interventions have different effects on the level

of corruption, and how these effects vary across the types of interventions.

3. To assess whether and how the effects of the interventions vary across developed and

developing countries.

4. To determine whether and how the effects of the interventions vary by unit of analysis

(e.g. government agencies vs civil servants) and by type of offence (e.g. bribery vs

misappropriation of public assets; nepotism vs extortion).

From the formulated objectives specific research questions emerge accordingly:

1. Which types of interventions (among the six identified by this review) significantly

reduce the risk of administrative corruption in the public sector?

2. Do different types of interventions have different effects on corruption?

3. Do the effect of a specific intervention change across developed and developing

countries? And if yes, to which extent does it change?

4. Do the effect of the interventions change by unit of analysis? And by type of offence?

How does it change? And if yes, to which extent does it change?

While pursuing the above-mentioned objectives, this project will also contribute in better

understanding the characteristics of administrative corruption and in shaping its peculiarities

across different contexts (developed and developing countries).

16 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

(3) METHODOLOGY

This systematic review aims at providing quantitative evidence on the effectiveness of

administrative anti-corruption strategies in the public sector.

In order to do so, it will synthetize evidence from quantitative studies, following Campbell and

Cochrane Collaboration approaches to systematic reviewing (Higgins & Green, 2011; Petticrew

& Roberst, 2006; Clarke & Oxman, 2000). Studies must be primary studies published or

unpublished.

Studies written in or translated into English, German, French, Italian, Spanish and

Vietnamese will be included in the review, as far as the project’s team include persons who are

fluent in these languages.

3.1. Criteria for including studies in the review

3.1.1. Type of study designs

Studies eligible for inclusion in this review must quantitatively assess the effects of the

administrative reforms on the level of corruption in a given context. The included studies have

to quantitatively measure the intervention either as a dichotomous, ordinal or scaled variable.

To be included in this review, studies should ideally use randomised controlled trials (RCT’s),

or any quasi-experimental method as study design. Therefore, we will include in this review

RCTs, cluster RCTs, quasi-RCTs, pretest-posttest two groups studies (with a non-equivalent

control group) and interrupted time series studies. The latter must have a clearly identifiable

time point at which the intervention occurred and must include information for at least three

time points before and after the intervention. Given the limited number of studies in this field

of research using any control groups, we will include also studies in which neither a control

group nor a random assignment is present, such as pretest-posttest one group studies and

cross-sectional studies like surveys (suchas the study of Yongqiang, 2011).

Both the definition of corruption and the criteria of inclusion are deliberately broad because

we are concerned about the limited number of possibly eligible studies. If a reasonable number

of studies (more than twenty) can be identified and located we shall consider restricting the

review to those studies meeting the highest methodological standards. At the documentary

stage, however, it seems safer to include as many studies as possible.

Anyway, we will include only those studies which clearly describe their research design and

clearly report the change in the level of administrative corruption due to a specific

intervention.

17 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

3.1.2. Types of participants

The review will include studies developed in low, middle and high income countries (defined

according to the World Bank classification method). For studies to be included they will need

to collect and report on data at an individual or aggregated level.

If the outcomes of interest are measured at an aggregate level, the units of analysis will be any

geographic place (e.g. community, city, province, state, region, or country) and/or

governmental agencies, public and private companies within a developed or developing

country. If the outcomes of interest are measured at an individual level, the unit of analysis

will be the individual (e.g. civil servants, representatives of governmental agencies, public and

private companies).

In particular, the review will include studies focusing on the following units of analysis:

Geographical areas (countries, regions, provinces, local municipalities),

Government agencies,

Public companies,

Private companies (e.g. surveys asking whether they have ever been requested to pay a

bribe to public officials),

Civil servants.

The type of unit of analysis depends on the different studies’ sources of data. For example,

studies considering the level of corruption as measured by administrative statistics, which

have specific geographical areas as unit of analysis, will consider as population a number of

provinces, local municipalities, or countries. On the other side, studies analyzing corruption

as measured by population surveys or self-report studies, will consider a population of

individuals or companies, which are the unit of analysis of such investigations.

The above-mentioned units of analysis will be analyzed separately, in order to highlight how

the impact of administrative measures on corruption differs across them.

3.1.3. Types of interventions

The types of interventions of this review, or the independent variables, are the

administrative anti-corruption reforms.

18 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

As mentioned in Chapter “Background”, Section 1.1, “Administrative corruption: the problem

of the review”, administrative corruption in this review is intended as “the abuse or misuse of

public office for private gain” and includes acts of bribery, fraud, extortion, embezzlement,

misappropriation or other diversion of property by a public official, theft of state assets or

diversion of state revenues, absenteeism, extortion, nepotism. Therefore, anti-corruption

interventions or reforms which are not specifically meant to curb or prevent these

administrative corrupt acts will be excluded from this review.

This systematic review will include administrative anti-corruption reforms without any

geographic and temporal limitations. The study of Hanna (2011: p. 17) demonstrated that

temporal exclusion criteria do not have much impact on the review’s findings because the

study of anti-corruption strategies has only taken off in recent years.

Furthermore, the administrative anti-corruption reforms considered for the review need to

concern reforms belonging to at least one of the following six main categories (see definitions

under section 1.3):

1. Economic

2. Educational

3. Cultural

4. Organisational or bureaucratic

5. Political

6. Judicial or repressive measures

Studies included in this review should clearly distinguish the types and characteristics of the

interventions (administrative reforms) according to the above-mentioned criteria.

The intervention has to be quantitatively measured. In particular, it could be measured either

as a dichotomous variable (e.g. presence / absence of a specific legislative reforms), ordinal

variable (e.g. long-term implementation of a specific legislative reform / medium-term

implementation / short-term implementation), or as a scaled variable (e.g. increased amount

of civil servants’ salaries).

19 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

3.1.4. Types of outcome measures

This review will include studies focused on interventions which have direct effects

on the level of administrative corruption, and which produce outcomes directly

related to our definition of administrative corruption (mentioned in Section 1.1,

p. 5)3. We are aware that, besides more direct impacts (such as the reduction in the level of

specific forms of corruption), interventions might also have indirect effects such as improved

public integrity, improved quality or quantity of specific public services (Bjorkmann and

Svensson 2009). Usually the latter are a consequence of the former and they are identifiable

only in the long-term period. It can also happen that interventions originally addressed to the

improvement of a specific public service, had an impact also on the level of corruption.

Furthermore, we understand that the outcome of specific anti-corruption reforms might have

a wider positive displacement than simply reduce the level of corruption. However, the

purpose of our review is to mainly focus on interventions with direct effects on the level

of administrative corruption. Such decision will help us not to get lost in other types of

outcome indicators, such as public service quality or access to public service. Nevertheless, to

not deny the relevance of these further outcomes, we would mention and classify them within

the review when it clearly appears they are direct consequences of the selected interventions.

Therefore, the type of outcome or the dependent variable of this review is the level of

administrative corruption4.

The dependent variable should be measured quantitatively. It means that the

assessment of the outcomes of the interventions (i.e. levels of corruption before and after the

intervention) should be quantitatively measured. The source of quantitative data to measure

the level of administrative corruption could be:

criminal justice statistics, i.e. number of cases of corruption reported to the police and

recorded by the police in a given context, the number of cases of corruption prosecuted.

surveys’ data of the general population or of particularly knowledgeable groups (such

as civil servants) that have assessed experience with corruption,

3 This review will consider the following main corrupt acts: bribery of public officials; embezzlement;

misappropriation or other diversion of property by a public official (theft of state assets or diversion of state

revenues), nepotism, as well as a range of corrupt behaviors such as trading in influence, abuse of function, illicit

enrichment. Some corruption-related concepts will also be included in the review such as fraud and extortion.

Fraud is a broader legal and popular term that covers both bribery and embezzlement. Extortion is a form of

corruption often seen in cases when state officials return preferential business opportunities and freedom from

taxation.

4 Ibidem.

20 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

and/or any other quantitative indicator on the experience and perception of corruption

(e.g. direct observations, self-report studies, etc.).

Studies including at least one of the above-mentioned measures of corruption will be included

in the systematic review.

3.1.5. Exclusion criteria

As articulated in Section 1.1., studies focused on political corruption are excluded from the

review.

Furthermore, as mentioned in Section 1.1 and in Section 3.1.2., studies which do not examine

administrative corruption offences and reforms with the involvement of at least one party as

the state or public office are excluded from the review (private on private corruption).

Studies not using a quantitative method of assessment of the outcome will be excluded (see

below for further details).

Qualitative and purely descriptive studies on anti-corruption strategies, as well as those

aiming at testing the causes and consequences of corruption are excluded from this review.

Indeed, even if these investigations may be interesting to understand the origins of corruption

and their interrelation with the social and economic environment of a given country, they will

not be included in this review because they do not measure the effects of anti-corruption

reforms.

3.1.6. Examples of studies eligible for inclusion

On the basis of the abovementioned criteria, this section provides some examples of studies

eligible for inclusion in this review.

1. Treisman, D. (2000). Decentralization and the quality of government.

This study statistically demonstrates how the degree of political decentralization in a country

can affect the quality of its government and the level of perceived corruption. The analyses of

the data on up to 154 countries suggest that states which have more tiers of government tend

to have higher perceived corruption.

2. Steves, F. and Rousso, A. (2003). Anti-corruption programmes in post-communist

transition countries and changes in the business environment, 1999-2002. European Bank

for Reconstruction and Development Working Paper No. 85.

Using the results of a large survey of firms across 24 post-communist transition countries, this

paper shows that omnibus anti-corruption programmes and membership in international

21 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

anti-corruption conventions have not led to reductions in the level of either administrative

corruption or state capture, between 1999 and 2002. Moreover, it finds out that the

implementation of anti-corruption programmes is positively correlated with the perception of

corruption.

3. Olken, B., A. (2005). Monitoring corruption: evidence from a field experiment in Indonesia.

Working paper 11753. National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, MA.

This study provides an example of ex-post cost-benefit analysis. The study quantifies in

monetary terms both the costs and the benefits of an anti-corruption intervention, after its

implementation. In particular, the author of this paper uses a randomized filed experiment to

examine different approaches to reducing corruption across 600 Indonesian village road

projects. He demonstrates that traditional top-down monitor can reduce corruption. In

particular, he finds out that “announcing an increased probability of government audit, from

a baseline of 4% to 100% reduced the missing expenditures (measured as discrepancies

between official project costs and an independent engineer’s estimate of costs) by about 8

percentage points”. On the other side he discovers that “increasing ‘grass-roots’ participation

in the monitoring process only reduced missing wages, with no effects on missing material

expenditure”. Overall, the net social benefits of this type of intervention were US$250 per

village, 150% more than the costs of the intervention (Johnson 2014: 6).

4. Yongqiang, N. (2011). Government Intervention, Perceived Benefit, and Bribery of Firms

in Transitional China. Journal of Business Ethics (2011) 104:175-184. Springer.

This study interview 600 business graduates (EMBA and MBA), working in different Chinese

companies, in order to understand if there are any relationship between government

intervention (in the forms of licenses, quotas, permits, approvals, authorizations, franchise

assignments, etc.) and bribery/corruption, and if this relationship was somehow mediated by

the firm’s perceived benefit it can get from the corrupt practice. The results show that the

government intervention causes bribery/corruption indeed, but a firm’s perceived benefit fully

mediates this relationship.

22 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

3.2. Search Strategy

In order to minimize publication bias, both published and unpublished studies, from a broad

range of international and national sources, will be included in this review.

The team members will perform a literature search to obtain papers and studies written in

English, German, French, Italian, Spanish and Vietnamese, including a quantitative

assessment of the effect of administrative anti-corruption reforms.

The literature search will be conducted within electronic databases, journals and websites.

In particular, among academic databases the review will focus on:

Social Science Citation Indexes

JSTOR, International Bibliography of Social Science

Social Science Research Network

Wiley Interscience

EBSCO Business Source Premier

EconLit

Google Scholar

Academic Search Premier (Ebsco)

ProQuest (Political Science, CSA Illumina, Public Affairs Information Service (PAIS

Inernational))

OVID (International Political Science Abstracts (IPSA))

With regards to academic journals, the search will be particularly focused on those presenting

an Economic and Development orientation, as well as a Sociological and Criminological

focus.

Databases including unpublished studies (grey literature), such as:

Campbell Crime and Justice Group

IDEAS (Internet Documents in Economics Access Service)

NBER (National Bureau of Economic Research)

23 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

Networked Digital Library of Theses

Dissertation Index to Theses,

DocTA (Doctoral Theses Archive)

Proquest’s Digital Dissertation

Rutgers Grey Literature Database

will also be investigated.

Online databases of key institutions, with more practitioner publications (rather than

academic), such as those of:

the Global Policing Database

the World Bank

the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD)

the Inter-American Development Bank

Regional development banks (African, Asian, etc.)

Innovations for Poverty Actions

Transparency International

U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre

Ernst and Young

PricewaterhouseCoopers

KPMG

will also be explored in order to collect relevant policy evaluations from a broad array of public,

private and no-profit institutions.

Online databases belonging to International and European organization such as:

the United Nations

the European Union (e.g. Group of States against Corruption (GRECO)

24 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

Transcrime

will also be searched, as well as national anti-corruption authorities’ website, such as:

Swiss State Secretary for Economic Affairs (SECO)

Italian National Anticorruption Authority (ANAC )

In addition, a screening of the references of the identified studies will be performed, in order

to run a citation search using the abovementioned databases. Conference programs of key

institutions mentioned above will also be investigated.

In case some key information is missing in included studies, the authors will be contacted.

Authors of particularly relevant studies may also be contacted in order to obtain further

materials or sister articles and documents.

The literature search will be mainly based on the groups of keywords presented in table 1

below. These keywords will be also combined using the Boolean operators OR and AND and

they will be translated in German, French, Italian, Spanish, Russian, Ukrainian and

Vietnamese.

25 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

Table 1- Groups of keywords used for the systematic review

Effects of anti-

Corruption Anti-corruption reform corruption Method

reform

corrupt* anti-corruption* reform* impact* quantitative*

administrative* anti- effect* statistical*

corruption* reform*

anti-corruption* approach* empirical*

bribery* anti-corruption* strategies* outcome* experimental*

favoritism* anti-corruption* interventions* result* quasi-

experimental*

nepotism* variable* economic*

embezzlement* administration* reform* effect* survey* econometric*

corrupt*

theft of state asset* grass-roots participation and evaluat* “random*

corruption* control trial*”

theft of state RCT*

revenues*

diversion of state regression*

assets*

diversion of state time series*

revenue*

misappropriation scientific*

of state property*

diversion of state

property*

integrity* integrity commission*

misconduct* crime and misconduct

commission*

All searches will be stored into EPPI-Reviewer, bibliographic tracking software dedicated to

systematic review, to ensure replicability.

3.3. Data extraction and study coding procedures

3.3.1. Selection of studies

All potential studies identified through the searches will be stored into reference management

software and duplicates removed.

Two independent review authors will start from reading the titles and abstracts of identified

studies in order to determine their eligibility against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. When a

title or abstract cannot be rejected with certainty, the full text of the article will be reviewed.

In case of disagreement between the two review authors at any stage, this will be resolved by

discussion, and if necessary, consultation with a third review author.

The included studies will be then organised into categories based on their methodological

approach, type of interventions, types of administrative corruption acts, geographical region

and other factors.

26 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

Studies that appear to be relevant but do not meet the inclusion criteria will be listed in the

table of excluded studies with reasons given for exclusion.

3.3.2. Data extraction and management

Data on the identified studies will be extracted independently by two review authors on the

basis of the template provided by the Cochrane Public Health Group.

In particular, the following information will be stored:

year of publication;

country of origin;

study design;

sample size;

recruitment details;

sample description;

theoretical basis for intervention;

intervention type;

delivery of intervention;

direct resource/cost requirements of the intervention;

duration of intervention and follow-up;

intensity of intervention;

outcomes (including scales/measures used, time points and results, effect sizes);

whether or not adverse outcomes were measured and reported;

potential moderators/confounders of study outcomes and any adjustment processes

used;

population characteristics;

27 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

process evaluation5 measures;

programme evaluation measures (if available) 6;

presence and extent of any bias in attrition

In case of disagreement about whether or not a study should be included, the lead author

(Professor Martin Killias) will act as arbitrator.

Data will be entered into Review Manager (RevMan 5) software and checked for accuracy.

A coding sheet with a description of the data collected is included in the appendixes.

3.3.3. Missing data

In case the selected studies do not report sufficient data to calculate effect sizes, we plan to

contact the authors of the studies and ask for them. In case the authors will or could not

provide the data, we will calculate response ratios effect size. The response ratio provides a

measure of the relative change in an outcome caused by an intervention. Besides some

limitations (see Borenstein et al. 2011), the response ratio offers good possibilities for

estimation.

3.3.4. Description of methods used in the component studies

Studies eligible for inclusion in this review must quantitatively assess the effects of the

administrative reforms on the level of corruption in a given context.

The method used by the studies covered by this review should ideally be based on randomised

control trials (RCT’s), such as the study of Olken (2005) (see summary on page 24).

Randomization and field experiments can be considered the most reliable methods to evaluate

anti-corruption initiatives, because they control well for bias, but they are not the most used.

Indeed, it is often difficult to randomly establish a control group and to obtain support by

decision makers or donor organizations (Johnsøn & Søreide 2013: 18). Therefore, quasi-

experimental methods will also be included in the review. According to Johnsøn & Søreide

(2013: 20) they are most applicable for evaluating large interventions targeting a large number

5Process evaluation or output evaluation relates to the assessment of ongoing activities and of the outputs they

produce. It focuses on whether activities are implemented according to plan and outputs are achieved on time

(Johnsøn & Søreide 2013: 13).

6Programme evaluation or outcome evaluation aim to produce evidence of whether the programme has

achieved its stated objectives (Johnsøn & Søreide 2013: 12)

28 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

of people or units. Eligible study designs include randomized controlled trials, natural

experiments, interrupted time-series designs, and any other quasi-experimental design with

or without control group (e.g. pretest-posttest two groups studies and pretest-posttest one

group studies), as well as cross-sectional studies like surveys (e.g. Yongqiang, 2011).

So far our review shows a prevalence of studies based on cross-sectional studies using ordinary

least square multiple regression analyses, such as the one of Yongqiang (2011) estimating the

effect of a government intervention on Chinese firms’ bribery, the one of Treisman (2000)

studying the impact of political decentralization on perceived corruption, and the study of

Steves and Rousso (2003) focusing on the relationship between anti-corruption programmes

and the level of administrative corruption.

3.3.5. Criteria for determination of independent findings

There may be different sources of non-independence of findings, the most important regards

the following issues:

1. Multiple indicators of the level of corruption reported in a single study (e.g. police

recorded cases, prosecuted cases). Only one will be selected for the analysis, taking into

consideration the most updated data and the comparability with the results of the other

studies included in the review.

2. Multiple outcomes or time-points within a single study on the same participants. In

case of different outcomes measured at multiple points in time (e.g. in time-series

studies where the level of corruption is measured 6 months after the implementation

of the reform, 12 months after and 3 years after) we will synthetize (average) multiple

effect size related to the same outcome from the same sample, prior to meta-analysis.

In particular, assuming an underlying uniform distribution for corruption we will

calculate an average effect size for the time points before the intervention, and an

average effect size for the time points after the intervention, and compare the two of

them We recognize that there are many other ways to deal with this type of time series

data (see Borenstein et al. 2009); however, given the research questions and the likely

nature of the intervention effect, we believe that this method is the most reliable and

parsimonious. In addition, even if we are aware that the effects of administrative

reforms usually take a while before producing tangible outcomes, we think it is

important to consider all the measurements of the same outcome at different points in

time. Any relevant difference in the same outcome at different points in time will be

reported within the results. It could, indeed, provide key information on the

functioning of a specific intervention as well as on the confounding effects of other

variables. In case of other study designs reporting multiple effect sizes for the same

29 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

outcome on the same participants, we will compute the mean of these effect sizes and

their variance (see Borenstein et al. 2009 for further details).

3. The same data being reported across multiple documents. The most complete and

detailed manuscript in terms of data availability and the most reliable according to the

risk of bias assessment will be designated as the primary coding source. We will make

sure that the effect sizes we calculate come from independent samples. In order to do

so, we will enter the information about each article/document into a data file (Excel)

and we will note down those cases where a sample may have overlapped with another

study. For each study, we will differentiate the unique outcomes derived from the same

sample, and then will combine multiple effect sizes describing the same outcome from

the same sample. We will then go again through the sample characteristics of our

studies to check that any effect sizes from different studies utilizing the same sample

will be combined together for our final analysis.

3.3.6. Details of study coding categories

Preliminary coding sheets have been produced for this protocol and included in its

appendixes. They illustrate the systematic method of extracting information regarding each

study’s characteristics, research design, participants, type of intervention, type of outcome,

risk of bias, etc.

Further table will be used to summarize the results of the critical appraisal for each study.

30 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

3.4. Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

When developing a systematic review, the most difficult source of bias to control for is the low

methodological quality of the selected studies (Jarde et al. 2012).

In order to ensure the selection of studies methodologically sound, the researchers will assess

the overall quality of each of them on the basis of the STROBE statement (Strengthening the

reporting of observational studies in epidemiology)7 checklist.

In addition, the potential specific risks of bias (selection bias, performance bias, detection bias,

attrition bias, reporting bias, and other potential risks) of included studies will be also assessed

using the relevant Cochrane EPOC (Effective Practice and Organisation of Care) “Risk of Bias”

tool8.

In particular, for studies with a separate control group (RCTs; NRCTs and CBA studies), the

overall risk of bias will be estimated as low, high or unclear, on the basis of the nine standard

criteria identified in the EPOC classification (1. Sequence generation, 2. Allocation

concealment, 3. Blinding of participants and personnel, 4. Blinding of outcome assessment, 5.

Incomplete outcome data, 6. Selective outcome reporting, 7. Other potential risks of bias). For

interrupted time series (ITS) studies, the overall risk of bias will be assessed on the basis of

the six standard criteria identified by EPOC (1. Independence of the intervention of secular

changes; 2. Pre-specification of the shape of the intervention effect; 3. Likelihood of the

intervention to affect data collection; 4. Blinding of outcome assessment; 5. Selective outcome

reporting; 6. Other potential risks of bias) (see also Petticrew & Roberts 2006: 138).

It has to be mentioned that, on the basis of the preliminary literature review we have

conducted, there are few true experimental or quasi-experimental studies providing data on

the effects of anti-corruption reforms, and, thus, several non-experimental studies will have

to be appraised before including them into the review.

Sanderson et al. (2007) highlighted that there is not a single and unanimously recognised tool

for assessing the quality of non-experimental studies. Discussion on this issue was developed

by Jarde et al. (2012 and 2013) in two different articles, leading to the creation of the tool Q-

Coh.

7 http://www.strobe-statement.org/index.php?id=available-checklists

8 See

http://epoc.cochrane.org/sites/epoc.cochrane.org/files/uploads/Suggested%20risk%20of%20bias%20criteria%

20for%20EPOC%20reviews.pdf

31 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

Following the checklists provided by the STROBE statement, the Q-Coh tool, and the

framework provided by Petticrew and Roberts (2006: 142) this review will assess the risk of

bias for non-experimental studies looking at four specific items which can affect the

methodological quality of a research:

a) Design of the study – The quality level of the design of non-experimental studies will

be evaluated as low, high or unclear by answering the following questions: 1. What question(s)

is the study aiming to answer?; 2. Was the study specifically designed with this question(s) in

mind?; 3. Are the setting, locations, population and data collection method of the study

carefully described? (Yes/No/DK); 4. Does the study clearly define all outcomes, predictors,

potential confounders, and effect modifiers? (Yes/No/DK for each item); 5. Does the study

provide sources of data and/or details of methods of measurement for each variable of

interest? (Yes/No/DK); 6. Does the study explain how the study size was arrived at?

(Yes/No/DK); 7. Does the study describe all statistical methods, including those used to

control for confounding? (Yes/No/DK); 8. Does the study explain how missing data were

addressed? (Yes/No/DK); 9. Does the study mention any effort to address potential sources of

bias? (Yes/No/DK).

b) Representativeness – In order to evaluate whether the results of a specific study could

be generalized from the sample to the target population, the following questions will be

answered: 1. Have the study participants been selected using a randomized sampling

procedure? (Yes/No/DK); 2. Is the similarity between the selected group of subjects and the

target population justified by the authors? (Yes, empirically/Yes, verbally/No); 3. Is the

sample surveyed representative? 4. In case of surveys, is the response rate high enough to

ensure that response bias is not a problem, or has response bias been analysed and shown not

significantly affect the study? 5. In case of surveys, has the same data collection method been

used across all population subgroups?; 6. Is the survey method likely to have introduced

significant bias?;

c) Outcome measure – In order to evaluate whether the measure of the outcome variable

reflects the true situation, the following questions will be answered: 1. Was the outcome

variable explicitly defined? (Yes/No/DK); 2. Is the outcome variable the most appropriate

measure for answering the study question? 3. Was the tool used to assess the outcome variable

valid? (Yes/Presumably/No); 4. Was the tool used to assess the outcome variable reliable?

(Yes/Presumably/No); 5. Was the tool used to assess the outcome appropriate?

(Probably/Unlikely).

d) Statistical control – In order to assess the level of reliability of the results, the following

questions will be answered: 1. Were known confounding factors accounted for in the design or

in the statistical analysis? (Yes/Partially/No); 2. Were other potential confounders taken into

account in the statistical analyses? (Yes/No); 3. Is there any potential confounder that was not

32 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

taken into account by the authors? (Probably none important/Probably/Yes). 4. Does the

study provide unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and

their precision (eg, 95% confidence interval)? (Yes/Partially/No); 5. Does the study make clear

which confounders were adjusted for and why they were include? (Yes/Partially/No).

On the basis of these evaluations we will provide each study with an assessment of the study

quality “weight”, the overall weight of evidence which the study provides. During this phase,

we will also provide technical details on analytical9 and statistical methods used to test the

effectiveness of the anti-corruption reforms.

To obtain a preliminary and visual assessment of the risk of bias, forest plots ordered by

judgements on each ‘Risk of bias’ entry will be analysed (through RevMan5). Forest plots on

the risk of bias are useful to provide a visual overview both of the relative contributions of the

studies at low, unclear and high risk of bias, and also of the extent of differences in intervention

effect estimates between studies at low, unclear and high risk of bias.

Effect sizes belonging to studies presenting different risk of bias will not be combined together.

In particular, studies with a ‘high’ or ‘unclear’ risk of bias will be kept separated from the main

analysis and treated as a separated category. Ideally, studies at high or unclear risk of bias

should be given reduced weight in meta-analyses, compared with studies at low risk of bias.

However, formal statistical methods to combine the results of studies at high and low risk of

bias are not sufficiently well developed. Therefore, the major approach is still to restrict meta-

analyses to studies at low (or lower) risk of bias, or to stratify studies according to risk of bias

(Spiegelhalter 2003).

3.4.1. Assessment of reporting bias

In order to assess whether there is a systematic difference between reported and unreported

findings, the following questions will be answered: 1. Were some outcomes, but not others,

selectively reported in the study depending on the nature and direction of the results?

(Yes/No). 2. Were the research findings published or non-published depending on the nature

and direction of the results? (Yes/No); 3. Were the publication of the research delayed

depending on the nature and direction of the results? (Yes/No); 5. Were the research findings

published in journals with different ease of access or levels of indexing in standard databases,

depending on the nature and direction of the results? (Yes/No).

In order to further check for publication bias, we will assess whether there are significant

differences between the results of published and unpublished studies, by using funnel plots to

33 The Campbell Collaboration | www.campbellcollaboration.org

assess the relationship between effect size and study precision and by running a sensitivity

analysis to identify the level of impact caused by different effect estimates in small studies.

Considering that the statistical significance of the results is often considered a requirement for

publication (Gerber & Malhotra 2008a, 2008b), a large number of published studies with a p-

values just below the standard 0.05 threshold can be considered a first sign of the presence of

publication bias (Molina 2013: 32).

3.5. Statistical procedures and conventions

Ideally, this project would comply with the standards of meta-analysis (as specified by Lipsey

and Wilson, 2001, or by Petticrew and Roberts, 2006) to synthetize the results of the

considered evaluations. The a-priori rule for conducting meta-analysis requires two or more

studies, each with a computable effect size of a common outcome construct, and similar

comparison conditions (Wilson et al., 2011).

3.5.1. Effect size extraction and transformation

According to the nature of the data being collected, the comparable effect size estimates will

be extracted from existing studies together with 95 percent confidence intervals. This effect

size data or data that can be used to calculate a standardized effect size will be recorded in

free-text format as part of the standardized coding sheet. A second reviewer will double-check

the coding and data extraction for every study that contains effect size data. All relevant data

will be input into Rev Man or Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software to calculate

standardized effect sizes and their standard errors and the conversion between effect size

types, to ensure that a common metric is used.