Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Blackfriars 1922-10 Where All Roads Lead 1

Încărcat de

tirachinas0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

6 vizualizări6 paginiBlackfriars 1922-10 Where All Roads Lead 1

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentBlackfriars 1922-10 Where All Roads Lead 1

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

6 vizualizări6 paginiBlackfriars 1922-10 Where All Roads Lead 1

Încărcat de

tirachinasBlackfriars 1922-10 Where All Roads Lead 1

Drepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 6

WHERE ALL ROADS LEAD

1. The Youth of the Church

NTIL about the end of the nineteenth century, a

man was expected to give his reasons for joining

the Catholic Church. To-day a man is really expected

to give his reasons for not joining it. This may seem an

exaggeration; but I believe it to stand for a subcon-

scious truth in thousands of minds. As for the funda-

mental reasons for a man doing it, there are only two

that are really fundamental. One is that he believes it

to be the solid objective truth, which is true whether he

likes it or not; and the other that he seeks liberation

from his sins. If there be any man for whom these are

not the main motives, it is idle to enquire what were

his philosophical or historical or emotional reasons for

joining the old religion; for he has not joined it at all.

But a preliminary word or two may well be said

about the other matter; which may be called the chal-

lenge of the Church. I mean that the world has re-

cently become aware of that challenge in a curiously

and almost creepy fashion. I am literally one of the

least, because one of the latest, of a crowd of converts

who have been thinking along the same lines as I.

There has been a happy increase in the number of

Catholics; but there has also been, if I may so express

it, a happy increase in the number of non-Catholics; in

the sense of conscious non-Catholics. The world has

become conscious that it is not Catholic. Only lately it

would have been about as likely to brood on the fact

that it was not Confucian. And all the array of reasons

for not joining the Church of Rome marked but the

beginning of the ultimate reason for joining it. At this

Copyright in United States.

37 1

Blac/driars

stage, let it be understood, I am speaking of a reaction

and rejection which was, as mine would once have been,

honestly if conventionally convinced. I am not speak-

ing now of the stage of mere self-deception or sulky

excuses; though such a stage there may be before the

end. I am remarking that even while we truly think

that the reasons are reasonable, we tacitly assume that

the reasons are required. Far back at the beginning of

all our changes, if I may speak for many much better

than myself, there was the idea that we must have rea-

sons for not joining the Catholic Church. I never had

any reasons for not joining the Greek Church, or the

religion of Mahomet, or the Theosophical Society or

the Society of Friends. Doubtless I could have dis-

covered and defined the reasons, had they been de-

manded; just as I could have found the reasons for

not going to live in Lithuania, or not being a chartered

accountant, or not changing my name to Vortigern

Brown, or not doing a thousand other things that it had

never 'occurred to me to do. But the point is that I

never felt the presence or pressure of the possibility at

all; I heard no distant and distracting voice calling me

to Lithuania or to Islam; I had no itch to explain to

myself why my name was not Vortigern or why my re-

ligion was not Theosophy. That sort of presence and

pressure of the Church I believe to be universal and

ubiquitous to-day; not only among Anglicans, but

among Agnostics. I repeat that I do not mean that

they have no real objections; on the contrary, I mean

that they have begun really to object; they have begun

to kick and struggle. One of the most famous modern

masters of fiction and social philosophy, perhaps the

most famous of all, was once listening to a discussion

between a High Church curate and myself about

the Catholic theory of Christianity. About half-way

through it, the great novelist began to dance wildly

about the room with characteristic and hilarious energy,

37 2

Where all Roads Lead

calling out, 'I'm not a Christian! I'm not a Christian!'

flapping about like one escaped as from the net of the

fowler. He had the sense of a huge vague army mak-

ing an encircling movement, and heading him and

herding him in the direction of Christianity and ulti-

mately Catholicism. He felt he had cut his way out

of the encirclement, and was not caught yet. With all

respect for his genius and sincerity, he had the air of

one delightedly doing a bolt, before anybody could

say to him, , Why do we not join the Catholic Church ?'

Now, I have noted first this common consciousness

of the challenge of the Church, because I believe it to

be connected with something else. That something

else is the strongest of all the purely intellectual forces

that dragged me towards the truth. It is not merely the

survival of the faith, but the singular nature of its sur-

vival. I have called it by a conventional phrase the

old religion. But it is not an old religion; it is a reli-

gion that refuses to grow old. At this moment of his-

tory it is a very young religion; rather especially a

religion of young men. It is much newer than the new

religions; its young men are more fiery, more full of

their subject, more eager to explain and argue than

were the young Socialists of my own youth. It does

not merely stand firm like an old guard; it has recap-

tured the initiative and is conducting the counter-

attack. In short, it is what youth always is rightly or

wrongly; it is aggressive. It is this atmosphere of the

aggressiveness of Catholicism that has thrown the old

intellectuals on the defensive. It is this that has pro-

duced the almost morbid self-consciousness of which

I have spoken. The converts are truly fighting, in

those words which recur like a burden at the opening

of the Mass, for a thing which giveth joy to their youth.

I cannot understand how this unearthly freshness in

something- so old can possibly be explained, except on

the supposition that it is indeed unearthly.

373

Blac/driars

A very distinguished and dignified example of this

paganism at bay is Mr. W. B. Yeates. He is a man I

never read or hear without stimulation; his prose is

even better than his poetry, and his talk is even better

than his prose. But exactly in this sense he is at bay;

and indeed especially so; for of course the hunt is up

in Ireland in much fuller cry than in England. And

if I wanted an example of the pagan defence at its

best, I could not ask for a clearer statement than the

following passage from his delightful memoirs in the

Af ercury; it refers to the more mournful poems of

Lionel Johnson and his other Catholic friends.

, I think it (Christianity) but deepened despair and multiplied

temptation . .. \\,hy are these strange souls born cvery-

v"here to-day, with hearts that Christianity, as shaped by his-

tory, cannot satisfy? Our love-letters wear out our love; no

school of painting outlasts its founders, every stroke of the

brush exhausts the impulse; pre-Raphaelitism had some twenty

year s, I mpressionism thirty perhaps. "'hy should we believe

that religion can never bring round its antithesis? Is it true

that our air is disturbed, as Mellarme said, "by the trembling

of the veil of the temple," or " that our whole age is seeking

to bring forth a sacred book? " Some of us thought that book

near towards the end of last century, but the tide sank again.'

Of course there are many minor criticisms of all this.

The faith only multiplies temptation in the sense that

it would multiply temptation to turn a dog into a man.

And it certainly does not deepe~ despair, if only for

two reasons; first, that despair to a Catholic is itself

a spiritual sin and blasphemy; and second, that the

despair of many pagans, often including Mr. Yeats,

could not possibly be deepened. But what concerns

me in these introductory remarks is his suggestion

about the duration of movements. When he gently

asks why Catholic Christianity should last longer than

other movements, we may well answer even more

gently, ' Why, indeed?' He might gain some light on

why it should, if he would begin by enquiring why it

374

Where all Roads Lead

does. He seems curiously unconscious that the very

contrast he gives is against the c.:ase he urges. If the

proper duration of a movement is twenty years, what

sort of a movement is it that lasts nearly two thousand?

If a fasliion should last no longer than Impression-

ism, what sort of a fashion is it that lasts about fifty

times as long? Is it just barely conceivable that it is

not a fashion?

But it is exactly here that the first vital consideration

recurs; which is not merely the fact that the thing re-

mains, but the manner in which it returns. By the

poet's reckoning of the chronology of such things, it

is amazing enough that one such thing has so survived.

It is much more amazing that it should have not sur-

vival, but revival, and revival with that very vivacity

for which the poet admits he has looked elsewhere, and

admits being disappointed when he looked elsewhere.

If he was expecting new things, surely he ought not to

be indifferent to something that seems unaccountably

to be as good as new. If the tide sank again, what

about the other tide that obviously rose again? The

truth is that, like many such pagan prophets, he ex-

pected to get something, but he certainly never ex-

pected to get what he got. He was expecting a tremb-

ling in the veil of the temple; but he never expected

that the veil of the most ancient temple would be rent.

He was expecting the whole age to bring forth a sacred

book; but he certainly never expected it to be a Mass-

book.

Yet this is really what has happened, not as a fancy

or a point of opinion, but as a fact of practical politics.

The nation to which his genius is an ornament has

been filled with a fury of fighting, of murder and of

martyrdom. God knows it has been tragic enough; but

it has certainly not been without that religious exalta-

tion that has so often been the twin of tragedy. Every-

one knows that the revolution has been full of religion,

375

Blac/driars

and of what religion? Nobody has m')re admiration

than I for the imaginative resurrections which Mr.

Yeats himself has effected, by the incantation of Celtic

song. But I doubt if Deirdre was the woman on whom

men called in battle; and it was not, I think, a por-

trait of Oisin that the Black-and-T an turned in shame

to the wall.

G. K. CHESTERTON.

(Mr. Chesterton will continue this series in the next number oJ

BLACKFRIARS. Editor. J

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Black and White 1892-01-16 The Changed HomeDocument2 paginiBlack and White 1892-01-16 The Changed HometirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Ballou's Monthly Magazine 1886-10 The Wife's SecretDocument6 paginiBallou's Monthly Magazine 1886-10 The Wife's SecrettirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Eclectic Magazine 1863-11 Phenomena of MissingDocument5 paginiThe Eclectic Magazine 1863-11 Phenomena of MissingtirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (894)

- The Eclectic Magazine 1880-07 An Anecdote of InstinctDocument6 paginiThe Eclectic Magazine 1880-07 An Anecdote of InstincttirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Tit-Bits 1883-04-28 Two First-Class PassengersDocument1 paginăTit-Bits 1883-04-28 Two First-Class PassengerstirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Eclectic Magazine 1864-02 Gleanings From Dark Annals. Coming To Life AgainDocument4 paginiThe Eclectic Magazine 1864-02 Gleanings From Dark Annals. Coming To Life AgaintirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Youth's Companion 1899-10-05 Editor and ContributorsDocument2 paginiThe Youth's Companion 1899-10-05 Editor and ContributorstirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Chapman's Magazine 1895-05 A Noiseless BurglarDocument4 paginiChapman's Magazine 1895-05 A Noiseless BurglartirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- An. Afternoon Chat With Payn.: MR Ja IesDocument3 paginiAn. Afternoon Chat With Payn.: MR Ja IestirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- June,: NonsenseDocument4 paginiJune,: NonsensetirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Eclectic Magazine 1881-12 The Victim of A VirtueDocument5 paginiThe Eclectic Magazine 1881-12 The Victim of A VirtuetirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jupiter's Stripes and Red SpotDocument6 paginiJupiter's Stripes and Red SpottirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Land & Water 1918-05-02 The Higher PunctualityDocument1 paginăLand & Water 1918-05-02 The Higher PunctualitytirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Eclectic Magazine 1854-09 ParodyDocument11 paginiThe Eclectic Magazine 1854-09 ParodytirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Land & Water 1918-02-14 New Secret DiplomacyDocument2 paginiLand & Water 1918-02-14 New Secret DiplomacytirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Land & Water 1917-Christmas Christmas and The PedantsDocument2 paginiLand & Water 1917-Christmas Christmas and The PedantstirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Land & Water 1917-10-18 Secret HistoryDocument2 paginiLand & Water 1917-10-18 Secret HistorytirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Land & Water 1918-08-08 Germanism in The Fourth YearDocument1 paginăLand & Water 1918-08-08 Germanism in The Fourth YeartirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Land & Water 1917-06-28 Why There Must Be VictoryDocument2 paginiLand & Water 1917-06-28 Why There Must Be VictorytirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Land & Water 1917-06-07 Our Tone in Transatlantic DiscussionDocument2 paginiLand & Water 1917-06-07 Our Tone in Transatlantic DiscussiontirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- America 1916-12-23 A Christmas CarolDocument1 paginăAmerica 1916-12-23 A Christmas CaroltirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- Land & Water 1916-12-07 The Industrious Apprentice and PatriotismDocument2 paginiLand & Water 1916-12-07 The Industrious Apprentice and PatriotismtirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- America 1916-08-05 The Slime From The DragonDocument2 paginiAmerica 1916-08-05 The Slime From The DragontirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Land & Water 1916-08-10 The Old and New TablesDocument2 paginiLand & Water 1916-08-10 The Old and New TablestirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- America 1916-12-16 The Question of Merry and HappyDocument2 paginiAmerica 1916-12-16 The Question of Merry and HappytirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- America 1916-04-22 The Thrift of ThoughtDocument2 paginiAmerica 1916-04-22 The Thrift of ThoughttirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- America 1916-12-30 The Democracy of ShakespeareDocument3 paginiAmerica 1916-12-30 The Democracy of ShakespearetirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- America 1916-10-14 On Losing One's HeadDocument1 paginăAmerica 1916-10-14 On Losing One's HeadtirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- America 1916-07-08 Mysticism and A Wooden PostDocument2 paginiAmerica 1916-07-08 Mysticism and A Wooden PosttirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- America 1916-05-06 Spring and The Story of GodDocument2 paginiAmerica 1916-05-06 Spring and The Story of GodtirachinasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Man and HisDocument97 paginiMan and Hisamir abbas zareiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Faerie Queen As An AllegoryDocument3 paginiFaerie Queen As An AllegoryAngel Arshi89% (18)

- Introduction To The Guan Yin Citta Dharma DoorDocument113 paginiIntroduction To The Guan Yin Citta Dharma Doormurthy2009Încă nu există evaluări

- Dependency in Linguistic Description, de Igor Mel'CukDocument114 paginiDependency in Linguistic Description, de Igor Mel'CukMarcelo Silveira100% (1)

- Bob Hill Predestination and Free Will Q&A 3Document89 paginiBob Hill Predestination and Free Will Q&A 3Chris FisherÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ueber Andronik Rhodos PDFDocument83 paginiUeber Andronik Rhodos PDFvitalitas_1Încă nu există evaluări

- Treasure Island Chapter 23Document11 paginiTreasure Island Chapter 23Ahsan SaleemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Title and ContentDocument5 paginiThesis Title and ContentKeerthiÎncă nu există evaluări

- "Le Cadavre Exquis Boira Le Vin Nouveau.": - Andre BretonDocument7 pagini"Le Cadavre Exquis Boira Le Vin Nouveau.": - Andre BretonKristan TybuszewskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Copy of Clean Modern Photo Article Page A4 DocumentDocument8 paginiCopy of Clean Modern Photo Article Page A4 DocumentHannya ChordevaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- 7929 Eurydice PDFDocument22 pagini7929 Eurydice PDFstemandersÎncă nu există evaluări

- DhanurmasaPujas SanskritDocument83 paginiDhanurmasaPujas Sanskritara1 RajÎncă nu există evaluări

- Powerful Dua for Health, Protection, Forgiveness and JannahDocument2 paginiPowerful Dua for Health, Protection, Forgiveness and JannahedoolawÎncă nu există evaluări

- Albert Camus - WorksDocument2 paginiAlbert Camus - WorksDiego Guedes100% (1)

- Kleptomaniac: Who's Really Robbing God Anyway Media Kit?Document10 paginiKleptomaniac: Who's Really Robbing God Anyway Media Kit?Frank Chase JrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Great Derangement: The Climate Change and The UnthinkableDocument10 paginiGreat Derangement: The Climate Change and The UnthinkableMahiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guru-Disciple Course Starts on May '11Document2 paginiGuru-Disciple Course Starts on May '11Mahesh DwivediÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seasons in ShadowDocument6 paginiSeasons in ShadowJarne VreysÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ibn Al-Arabi and Joseph Campbell Akbari PDFDocument16 paginiIbn Al-Arabi and Joseph Campbell Akbari PDFS⸫Ḥ⸫RÎncă nu există evaluări

- 32IJELS 109202043 Oedipal PDFDocument3 pagini32IJELS 109202043 Oedipal PDFIJELS Research JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- DCC DE1 PlayersLibram Complete ScreenresDocument66 paginiDCC DE1 PlayersLibram Complete Screenresjack100% (3)

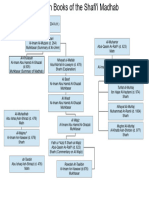

- Main Books of Shafii Madhhab ChartDocument1 paginăMain Books of Shafii Madhhab ChartM. A.Încă nu există evaluări

- Analysis On Elizabeth Browning's How Do I Love TheeDocument2 paginiAnalysis On Elizabeth Browning's How Do I Love TheeElicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World (MODULE)Document17 pagini21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World (MODULE)Tam EstrellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- EAPP Module 1 Week 1Document12 paginiEAPP Module 1 Week 1CallixÎncă nu există evaluări

- Session Guide SampleDocument7 paginiSession Guide SampleJake Ryan Bince CambaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Angels and Angelology in The Middle AgesDocument271 paginiAngels and Angelology in The Middle Agesanon100% (5)

- Stupa ConsecrationDocument439 paginiStupa ConsecrationUrgyan Tenpa Rinpoche100% (6)

- Period of EnlightenmentDocument50 paginiPeriod of EnlightenmentJames YabyabinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Out of the Dark: My Journey Through the Shadows to Find God's JoyDe la EverandOut of the Dark: My Journey Through the Shadows to Find God's JoyEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (10)

- The Dangers of a Shallow Faith: Awakening From Spiritual LethargyDe la EverandThe Dangers of a Shallow Faith: Awakening From Spiritual LethargyEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (134)

- Now and Not Yet: Pressing in When You’re Waiting, Wanting, and Restless for MoreDe la EverandNow and Not Yet: Pressing in When You’re Waiting, Wanting, and Restless for MoreEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (4)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsDe la EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bait of Satan: Living Free from the Deadly Trap of OffenseDe la EverandBait of Satan: Living Free from the Deadly Trap of OffenseEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (307)

- Out of the Dark: My Journey Through the Shadows to Find God's JoyDe la EverandOut of the Dark: My Journey Through the Shadows to Find God's JoyEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (5)