Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

History of Abortion

Încărcat de

Aaron Philip DuranTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

History of Abortion

Încărcat de

Aaron Philip DuranDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

HISTORY OF ABORTION

Over several centuries and in different cultures, there is a rich history of women helping each

other to abort. Until the late 1800s, women healers in Western Europe and the U.S. provided

abortions and trained other women to do so, without legal prohibitions.

The State didn't prohibit abortion until the 19th century, nor did the Church lead in this new

repression. In 1803, Britain first passed antiabortion laws, which then became stricter

throughout the century. The U.S. followed as individual states began to outlaw abortion. By

1880, most abortions were illegal in the U.S., except those ``necessary to save the life of the

woman.'' But the tradition of women's right to early abortion was rooted in U.S. society by then;

abortionists continued to practice openly with public support, and juries refused to convict them.

Abortion became a crime and a sin for several reasons. A trend of humanitarian reform in the

mid-19th century broadened liberal support for criminalization, because at that time abortion

was a dangerous procedure done with crude methods, few antiseptics, and high mortality rates.

But this alone cannot explain the attack on abortion. For instance, other risky surgical

techniques were considered necessary for people's health and welfare and were not prohibited.

``Protecting'' women from the dangers of abortion was actually meant to control them and

restrict them to their traditional child-bearing role. Antiabortion legislation was part of an

antifeminist backlash to the growing movements for suffrage, voluntary motherhood, and other

women's rights in the 19th century. *For more information, see Linda Gordon's Woman's Body,

Woman's Right, rev. ed. (New York: Penguin Books, 1990).

At the same time, male doctors were tightening their control over the medical profession.

Doctors considered midwives, who attended births and performed abortions as part of their

regular practice, a threat to their own economic and social power. The medical establishment

actively took up the antiabortion cause in the second half of the 19th century as part of its effort

to eliminate midwives.

Finally, with the declining birth rate among whites in the late 1800s, the U.S. government and

the eugenics movement warned against the danger of ``race suicide'' and urged white, native-

born women to reproduce. Budding industrial capitalism relied on women to be unpaid

household workers, low-paid menial workers, reproducers, and socializers of the next

generation of workers. Without legal abortion, women found it more difficult to resist the

limitations of these roles.

Then, as now, making abortion illegal neither eliminated the need for abortion nor prevented its

practice. In the 1890s, doctors estimated that there were two million abortions a year in the U.S.

(compared with one and a half million today). Women who are determined not to carry an

unwanted pregnancy have always found some way to try to abort. All too often, they have

resorted to dangerous, sometimes deadly methods, such as inserting knitting needles or coat

hangers into the vagina and uterus, douching with dangerous solutions like lye, or swallowing

strong drugs or chemicals. The coat hanger has become a symbol of the desperation of millions

of women who have risked death to end a pregnancy. When these attempts harmed them, it

was hard for women to obtain medical treatment; when these methods failed, women still had to

find an abortionist.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

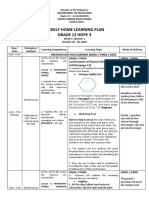

- 4th WHLP IN P.E12Document2 pagini4th WHLP IN P.E12Aaron Philip DuranÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- 2nd WHLP IN P.EDocument4 pagini2nd WHLP IN P.EAaron Philip DuranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Practical Research 2 Weekly Home Learning PlanDocument3 paginiPractical Research 2 Weekly Home Learning PlanAaron Philip DuranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- RamDocument1 paginăRamAaron Philip DuranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- KnivesDocument2 paginiKnivesAaron Philip DuranÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Essay - Pros and Cons of Genetic EngineeringDocument1 paginăEssay - Pros and Cons of Genetic EngineeringAaron Philip DuranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gen Physics 1 Module Week 2Document37 paginiGen Physics 1 Module Week 2Aaron Philip DuranÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Topic 3 Health Teaching PlanDocument1 paginăTopic 3 Health Teaching PlanAaron Philip DuranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- History of AbortionDocument1 paginăHistory of AbortionAaron Philip DuranÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- History of Philippine Sports PDFDocument48 paginiHistory of Philippine Sports PDFGerlie SaripaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Managing a Patient with Pneumonia and SepsisDocument15 paginiManaging a Patient with Pneumonia and SepsisGareth McKnight100% (2)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Fill in The BlanksDocument38 paginiFill in The Blanksamit48897Încă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Mr. Bill: Phone: 086 - 050 - 0379Document23 paginiMr. Bill: Phone: 086 - 050 - 0379teachererika_sjcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- Prep - VN: Where Did The Polo Family Come From?Document1 paginăPrep - VN: Where Did The Polo Family Come From?Phương LanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- Helen Hodgson - Couple's Massage Handbook Deepen Your Relationship With The Healing Power of TouchDocument268 paginiHelen Hodgson - Couple's Massage Handbook Deepen Your Relationship With The Healing Power of TouchLuca DatoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The Butterfly Effect movie review and favorite scenesDocument3 paginiThe Butterfly Effect movie review and favorite scenesMax Craiven Rulz LeonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 8, Problem 7PDocument2 paginiChapter 8, Problem 7Pmahdi najafzadehÎncă nu există evaluări

- Principles of DisplaysDocument2 paginiPrinciples of DisplaysShamanthakÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Computer Conferencing and Content AnalysisDocument22 paginiComputer Conferencing and Content AnalysisCarina Mariel GrisolíaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Felomino Urbano vs. IAC, G.R. No. 72964, January 7, 1988 ( (157 SCRA 7)Document1 paginăFelomino Urbano vs. IAC, G.R. No. 72964, January 7, 1988 ( (157 SCRA 7)Dwight LoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 100 Bedded Hospital at Jadcherla: Load CalculationsDocument3 pagini100 Bedded Hospital at Jadcherla: Load Calculationskiran raghukiranÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Reduce Home Energy Use and Recycling TipsDocument4 paginiReduce Home Energy Use and Recycling Tipsmin95Încă nu există evaluări

- Simple Future Vs Future Continuous Vs Future PerfectDocument6 paginiSimple Future Vs Future Continuous Vs Future PerfectJocelynÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gcu On Wiki PediaDocument10 paginiGcu On Wiki Pediawajid474Încă nu există evaluări

- Plo Slide Chapter 16 Organizational Change and DevelopmentDocument22 paginiPlo Slide Chapter 16 Organizational Change and DevelopmentkrystelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Napolcom. ApplicationDocument1 paginăNapolcom. ApplicationCecilio Ace Adonis C.Încă nu există evaluări

- Financial Accounting and ReportingDocument31 paginiFinancial Accounting and ReportingBer SchoolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Decision Support System for Online ScholarshipDocument3 paginiDecision Support System for Online ScholarshipRONALD RIVERAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Treviranus ThesisDocument292 paginiTreviranus ThesisClaudio BritoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Concepts of Human Development and Poverty: A Multidimensional PerspectiveDocument3 paginiConcepts of Human Development and Poverty: A Multidimensional PerspectiveTasneem Raihan100% (1)

- 3 People v. Caritativo 256 SCRA 1 PDFDocument6 pagini3 People v. Caritativo 256 SCRA 1 PDFChescaSeñeresÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Secret Path Lesson 2Document22 paginiThe Secret Path Lesson 2Jacky SoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Present Tense Simple (Exercises) : Do They Phone Their Friends?Document6 paginiPresent Tense Simple (Exercises) : Do They Phone Their Friends?Daniela DandeaÎncă nu există evaluări

- City Government of San Juan: Business Permits and License OfficeDocument3 paginiCity Government of San Juan: Business Permits and License Officeaihr.campÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group Assignment Topics - BEO6500 Economics For ManagementDocument3 paginiGroup Assignment Topics - BEO6500 Economics For ManagementnoylupÎncă nu există evaluări

- ANA Stars Program 2022Document2 paginiANA Stars Program 2022AmericanNumismaticÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gambaran Kebersihan Mulut Dan Karies Gigi Pada Vegetarian Lacto-Ovo Di Jurusan Keperawatan Universitas Klabat AirmadidiDocument6 paginiGambaran Kebersihan Mulut Dan Karies Gigi Pada Vegetarian Lacto-Ovo Di Jurusan Keperawatan Universitas Klabat AirmadidiPRADNJA SURYA PARAMITHAÎncă nu există evaluări

- AReviewof Environmental Impactof Azo Dyes International PublicationDocument18 paginiAReviewof Environmental Impactof Azo Dyes International PublicationPvd CoatingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bias in TurnoutDocument2 paginiBias in TurnoutDardo CurtiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)