Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Castillo v. Castillo 23 Phil 365

Încărcat de

Anonymous ymCyFq0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

28 vizualizări4 paginiTitlu original

13. Castillo v. Castillo 23 Phil 365.docx

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

28 vizualizări4 paginiCastillo v. Castillo 23 Phil 365

Încărcat de

Anonymous ymCyFqDrepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca DOCX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 4

FIRST DIVISION

[G.R. No. 7050. November 5, 1912.]

NACARIA CASTILLO ET AL., plaintiffs-appellees, vs.

URBANO CASTILLO and MARIA QUIZON, defendants-

appellants.

Vicente Agregado and Godofredo Reyes for appellants.

Jose Mayo Librea for appellees.

SYLLABUS

1. ESTATES; SETTLEMENT OF ESTATES WITHOUT LEGAL

PROCEEDINGS. — Under the heading of settlement of estates, etc., Act

No. 190, section 596, provides that when all heirs of a person dying without

a will are of age and have legal capacity, and when there are no debts

against the estate, or when the latter have been satisfied by the heirs or by

mutual agreement in due form and properly signed, the said heirs may divide

the estate in such manner as may seem best to them, without recourse to

the courts; therefore, the law does not support the doctrine set up by the

appellant, to the effect that heirs of age cannot call for the division of realty,

left by their ancestor and held by one of the coheirs, without instituting

special proceedings and securing the appointment of a judicial administrator

as the only person authorized to take charge of the estate.

DECISION

ARELLANO, C.J : p

The subject of this suit is a parecel of agricultural land, situated in

the barrio of Galamayano, municipality of San Jose, Province of Batangas,

of an area such as is usually required for sowing thirty gantas of seed-rice,

and described and identified by boundaries. It is taken for granted that this

land belonged to Simona Madlangbayan, who died seven years ago. At the

present time it is in the exclusive possession of one of the latter's children,

Urbano Castillo, while there are other descendants of hers who have the

same right, to wit: A daughter and some grandchildren of the deceased

brother of full blood of Urbano Castillo, named Pio Castillo; the daughter of

a sister of full blood of the same defendant, named Alfonsa, likewise

deceased; and a daughter of a half-brother of the said Urbano Castillo,

named Estefano Libingting, also deceased. The descendants of these

three family branches claim to be entitled to share with Urbano Castillo the

ownership of the land in question, as being the only property Simona

Madlangbayan had left at her death. Hence, the demand for a division,

which is the object of this suit, although Alfonsa Castillo's daughter figures

as a defendant therein merely by default.

The defendant Urbano Castillo, as the sole possessor of the land,

endeavored to prove that his mother, Simona Madlangbayan, had other

property which during her lifetime she disposed of to the benefit of some of

the plaintiffs; but the lower court held that this allegation had not been

proven, and such conclusion must be affirmed as it is well-founded and in

no wise erroneous.

In the judgment rendered the claim made by the plaintiffs was

recognized to be valid and the property of joint-ownership was ordered to

be divided into four parts: One, for Macaria Castillo and her nephews and

nieces, Juan, Clemente, Pedro, Lope, Tomasa, and Maria, all surnamed

Cadano; another, for Juliana Libingting; another, for Maria Quizon; and the

fourth, for the defendant Urbano Castillo.

The latter entered an exception to this judgment, moved for a

rehearing, excepted to the ruling denying the same, and filed a bill of

exceptions, which, however, was held on file until the conclusion of the trial

and during the progress of the proceedings had for the division, award of

shares and liquidation of fruits, which operations wee all effected through

commissioners and as a result thereof the court ordered: (1) That each

coparcener be delivered the part of the property shown on the rough

sketch made by the commissioners, to belong to him or her; (2) that

Urbano Castillo pay to each coparcener, as reimbursement of fruits,

P78.18; and (3) that the expense of partition be borne pro rata by all the

interested parties.

When, after all this procedure, the case was brought before us on

appeal, through the proper bill of exceptions, the judgment was not

impugned on account of the form of division therein ordered, but merely

because of the following assignments of error:

1. Because the personality of the plaintiffs was recognized, and the

amendment of the answer, impugning such personality, was disallowed.

2. Because the instrument of gift was held to be false, and the gift

null and void.

3. Because an indemnity for the fruits was awarded. With respect to

the first assignment of error, it is not a principle authorized by law that heirs

of legal age may not demand the division of a real property, left them by

their predecessor-in-interest and held by a coheir, without first initiating

special intestate proceedings during which a judicial administrator is to be

appointed, who alone is vested with the personality to claim the property

that belongs to the succession. On the contrary, such heirs are expressly

authorized to do so, unless, for the reason of there being unpaid debts,

judicial intervention becomes necessary, which was not alleged as a

special defense in this suit.

As much for the preceding reasons as because there was not

included in the bill of exceptions the question relative to the opportune or

inopportune motion presented for an amendment of the answer to the

complaint, and which was denied by the lower court, such assignment of

error, alleged in this instance, can neither be considered nor decided.

With reference to the second alleged error, the document declared in

the judgment appealed from to be false, null and void, is one of gift which

the appellant avers was executed in his behalf by his predecessor-in-

interest. The finding of falsity, contained in the judgment of the lower court

and based on various facts discussed by him in detail, can not be brought

up in this appeal except as a question of fact, with regard to which no new

matter may be introduced inasmuch as no error of fact was alleged to have

been committed in weighing the evidence; and the cogent presumption of

law, which can not easily be destroyed except by strong contrary evidence

— the only reason advanced by the appellant — reenforces the old public

instruments executed in conformity with the Notarial Law, (now repealed)

before a notary public, by reason of their insertion in the protocol or notarial

registry and the personal attestation made by that official of the

proceedings and the contents of the instrument — characteristic features

not enjoyed by a private instrument which, executed on one date, like the

one in question (January 20, 1902), appears to have been ratified on

another (November 15, 1905), before a notary, but with no further

authorization on the part of this official other than such act of affirmation.

And even though the said instrument were not false, the trial court

declared it to be void and ineffective. The alleged gift was in fact null and

void, according to the provisions of articles 629 and 633 of the Civil Code,

as its acceptance by the done was in no manner expressed in the

instrument, nor was the pretended gift consummated pursuant to the

provision contained in article 623 of the same code.

The appellant argues that the acceptance in writing of the gift in

question, was not necessary, as it was made for a valuable consideration,

and should be subject to the legal provisions governing contracts. If this

alleged fit was really made, it was one of those mentioned in article 619 of

the aforecited code, as being a fight "which imposes upon the done a

burden inferior to the value of the gift," for Simona Madlangbayan

apparently stated in the said instrument that she delivered the land to

Urbano Castillo in order that he defray the expenses of her subsistence

and burial, "and if perchance anything should remain from the price of the

land, the surplus of the said expenses (?) is granted to him by me." A gift of

this kind is not in fact a gift for a valuable consideration, but is

remuneratory or compensatory, made for the purpose of remunerating or

compensating a charge, burden or condition imposed upon the done,

inferior to the value of the gift which, therefore, may very properly be

termed to be conditional, and article 622, invoked by the appellant himself,

very clearly prescribes that "gifts for valuable consideration shall be

governed by the provisions of this title with regard to the part exceeding the

value of the charge that the said instrument was false as shown by the

evidence and in accordance with which the defendant did not fulfill the

conditions mentioned, since he did not defray the expenses for the

subsistence and burial of Simona Madlangbayan.

With regard to the third assignment of error, the appellant contends

that no reimbursement of fruits should have been awarded the plaintiffs, as

no demand for the same was made in the complaint and he was unable to

prepare evidence in the matter. The procedure had after the plaintiffs were

found to be entitled to the right of coownership, was in all respects in

accord with the provisions of section 191 of the Code of Civil Procedure,

and so well prepared was the appellant in the second part of the trial, for

the presentation of evidence, that he stated himself "I do not even wish to

cross-examine" (his brief, p. 10).

The judgment appealed from is affirmed, with the costs of this

instance against the appellant. So ordered.

Torres, Mapa, Johnson, Carson, and Trent, JJ., concur.

||| (Castillo v. Castillo, G.R. No. 7050, [November 5, 1912], 23 PHIL 364-368)

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Case Digest Success1Document26 paginiCase Digest Success1Keysie Gomez100% (1)

- Cases in ContractsDocument13 paginiCases in ContractsEstrell VanguardiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 de Los Santos v. JarraDocument4 pagini1 de Los Santos v. JarraShairaCamilleGarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Digest For Law On PropertyDocument3 paginiCase Digest For Law On PropertyJohn Charel Sabandal PongaseÎncă nu există evaluări

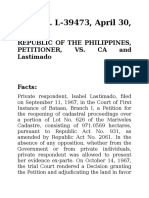

- Republic Vs CA and LastimadoDocument6 paginiRepublic Vs CA and LastimadoSachuzenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gabriel vs. RD of RizalDocument3 paginiGabriel vs. RD of RizalAntonio Paolo Alvario100% (2)

- Republic of The Philippines, Petitioner, vs. Hon. Court of Appeals and Isabel Lastimado, RespondentsDocument6 paginiRepublic of The Philippines, Petitioner, vs. Hon. Court of Appeals and Isabel Lastimado, RespondentsSachuzenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Midterm Civil Procedure CasesDocument77 paginiMidterm Civil Procedure CasesR-lheneFidelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Municipal Council vs. Colegio de San Jose (Escheat)Document6 paginiMunicipal Council vs. Colegio de San Jose (Escheat)Alvin NiñoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4 Salazar vs. SalazarDocument7 pagini4 Salazar vs. SalazarAnjÎncă nu există evaluări

- Suntay Vs SuntayDocument7 paginiSuntay Vs SuntayAileen RoseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Republic Vs CA and LastimadoDocument7 paginiRepublic Vs CA and LastimadoSachuzenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Matias Hilado, For Appellant. Jose Felix Martinez, For AppelleeDocument51 paginiMatias Hilado, For Appellant. Jose Felix Martinez, For AppelleeIyah MipangaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supreme Court: Romualdo D. Celestra For Petitioner-Appellee. Balcos, Salazar & Associates For Oppositor-AppellantDocument4 paginiSupreme Court: Romualdo D. Celestra For Petitioner-Appellee. Balcos, Salazar & Associates For Oppositor-AppellantAmanda HernandezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Es CheatDocument14 paginiEs CheatJoy OrenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Warner, Barnes & Co., Ltd. v. Luzon Surety Co., Inc.Document3 paginiWarner, Barnes & Co., Ltd. v. Luzon Surety Co., Inc.samantha.makayan.abÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. L-45625 (Case Study) PDFDocument3 paginiG.R. No. L-45625 (Case Study) PDFShannah Marie AsperinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rule 81 - Warner vs. LuzonDocument2 paginiRule 81 - Warner vs. LuzonMhaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agoncillo & Ilustre, C. H. Gest,: 184 Philippine Reports AnnotatedDocument7 paginiAgoncillo & Ilustre, C. H. Gest,: 184 Philippine Reports AnnotatedRaiya AngelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendant-Appellant Matias Hilado, Jose Felix MartinezDocument4 paginiPlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendant-Appellant Matias Hilado, Jose Felix MartinezGericah RodriguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Specpro.09.Salazar vs. Court of First Instance of Laguna and Rivera, 64 Phil. 785 (1937)Document12 paginiSpecpro.09.Salazar vs. Court of First Instance of Laguna and Rivera, 64 Phil. 785 (1937)John Paul VillaflorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Municipal Council of San Pedro Laguna vs. Colegio de San JoseDocument3 paginiMunicipal Council of San Pedro Laguna vs. Colegio de San JoseaudreyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ross, Lawrence and Selph For Appellant. Camus and Delgado For AppelleeDocument12 paginiRoss, Lawrence and Selph For Appellant. Camus and Delgado For Appelleebrida athenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chiong Joc-Soy v. VañoDocument5 paginiChiong Joc-Soy v. VañoSecret BookÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nego - D (Cases)Document6 paginiNego - D (Cases)Rona AnyogÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cases Civ PRO DigestDocument10 paginiCases Civ PRO DigestPaolo BargoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 34 Valencia Vs JimenezDocument5 pagini34 Valencia Vs JimenezLegaspiCabatchaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Montinola Vs VillanuevaDocument6 paginiMontinola Vs VillanuevaJay TabuzoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Land Patent-Full CasesDocument88 paginiLand Patent-Full CasesRowenaSajoniaArenga100% (1)

- De Los Santos Vs JarraDocument2 paginiDe Los Santos Vs JarraEmilie DeanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jose Mcmicking, Sheriff of Manila, PlaintiffDocument9 paginiJose Mcmicking, Sheriff of Manila, PlaintiffCiena MaeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bonifacio P. Legaspi For Plaintiff-Appellant. Cecilio P. Luminarias For Defendants-AppelleesDocument51 paginiBonifacio P. Legaspi For Plaintiff-Appellant. Cecilio P. Luminarias For Defendants-AppelleesAllen AntonioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maneclang V Baun Case DigestDocument4 paginiManeclang V Baun Case Digestmarmiedyan9517Încă nu există evaluări

- Digest All Cases From Reliable SourceDocument10 paginiDigest All Cases From Reliable SourceJasper PelayoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 13 - GSIS vs. CADocument5 pagini13 - GSIS vs. CARoland Joseph MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ARTICLE 1355 - Effect of Lesion or Inadequacy of Cause - Portland Cement Co. vs. Dumon Askay vs. CosalanDocument4 paginiARTICLE 1355 - Effect of Lesion or Inadequacy of Cause - Portland Cement Co. vs. Dumon Askay vs. CosalanFrances Tracy Carlos PasicolanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Delos Santos V JarraDocument4 paginiDelos Santos V Jarracmv mendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- US vs. Gregorio Et - Al. Case DigestDocument5 paginiUS vs. Gregorio Et - Al. Case DigestPaulo GomezÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2Chp2 - Gabriel Vs RD of Rizal - GR No L-17956Document4 pagini2Chp2 - Gabriel Vs RD of Rizal - GR No L-17956Dora the ExplorerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Villanueva v. SantosDocument3 paginiVillanueva v. SantosJose Edmundo DayotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motion To Dismiss NotesDocument30 paginiMotion To Dismiss Notescmv mendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1908 Velasco - v. - Masa20210424 12 11bjt5jDocument5 pagini1908 Velasco - v. - Masa20210424 12 11bjt5j19105259Încă nu există evaluări

- Castillo Vs CastilloDocument3 paginiCastillo Vs CastilloMark Evan GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. L-34362 November 19, 1982 Modesta Calimlim vs. Hon. Pedro A. RamirezDocument3 paginiG.R. No. L-34362 November 19, 1982 Modesta Calimlim vs. Hon. Pedro A. RamirezPsychelynne Maggay NicolasÎncă nu există evaluări

- De Bautista Vs de GuzmanDocument10 paginiDe Bautista Vs de GuzmanGeeanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gaotian Vs GaffudDocument8 paginiGaotian Vs GaffudCarol JacintoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ganuelas Vs CawedDocument7 paginiGanuelas Vs CawedDanny DayanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Palma vs. Cañizares, 1 Phil., 602, December 31, 1902Document5 paginiPalma vs. Cañizares, 1 Phil., 602, December 31, 1902Campbell HezekiahÎncă nu există evaluări

- F 11. St. Dominic Corp V IACDocument1 paginăF 11. St. Dominic Corp V IACChilzia RojasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dignos Ys. Court of Appeals158 Scra 378 FactsDocument11 paginiDignos Ys. Court of Appeals158 Scra 378 FactsCherie AguinaldoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legaspi V CADocument7 paginiLegaspi V CAElizabeth LotillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MontinolaDocument4 paginiMontinolaMona LizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Delos Santos V Jarra - Carpo V ChuaDocument22 paginiDelos Santos V Jarra - Carpo V ChuaSteph RentÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11.cabaliw and Sadorra v. Sadorra, Et Al. G.R. No. L-25650, June 11, 1975Document8 pagini11.cabaliw and Sadorra v. Sadorra, Et Al. G.R. No. L-25650, June 11, 1975Cyrus Pural EboñaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Montinola Vs Villanueva GR NO. L 26008Document4 paginiMontinola Vs Villanueva GR NO. L 26008rachel cayangaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Set 1 Full TextDocument18 paginiSet 1 Full TextAubrey SindianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Delos Santosvs JarraDocument4 paginiDelos Santosvs JarraGorgeousEÎncă nu există evaluări

- SalesDocument196 paginiSalesJoy OrenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionDe la EverandSupreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionÎncă nu există evaluări

- PCIB v. Escolin GR L-27860Document106 paginiPCIB v. Escolin GR L-27860Anonymous ymCyFqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hernandez v. Andal 78 Phil 197Document11 paginiHernandez v. Andal 78 Phil 197Anonymous ymCyFqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Antonietta Garcia Vda. de Chua v. CA GR 116835Document11 paginiAntonietta Garcia Vda. de Chua v. CA GR 116835Anonymous ymCyFqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pacific Bankig Corp. Employees Org. v. CA GR 109373Document14 paginiPacific Bankig Corp. Employees Org. v. CA GR 109373Anonymous ymCyFqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Family Code Art 381-396, NCC Sujested CaseDocument2 paginiFamily Code Art 381-396, NCC Sujested CaseistefifayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cuenco v. CA 53 SCRA 360Document11 paginiCuenco v. CA 53 SCRA 360Anonymous ymCyFqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Matute v. CA 26 Scra 768Document24 paginiMatute v. CA 26 Scra 768Anonymous ymCyFqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roberts Vs Leonidas - G.R. No. 55509. April 27, 1984Document4 paginiRoberts Vs Leonidas - G.R. No. 55509. April 27, 1984Ebbe DyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Benedicto v. Javellana 10 Phil 197Document4 paginiBenedicto v. Javellana 10 Phil 197Anonymous ymCyFqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jimenez v. IAC GR 75773Document5 paginiJimenez v. IAC GR 75773Anonymous ymCyFqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Utulo v. Pasion Vda. de Garcia 66 Phil 302Document6 paginiUtulo v. Pasion Vda. de Garcia 66 Phil 302Anonymous ymCyFqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Garcia Fule v. CADocument12 paginiGarcia Fule v. CARichard KoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fernandez v. Maravilla 10 SCRA 589 HIGHLIGHTEDDocument6 paginiFernandez v. Maravilla 10 SCRA 589 HIGHLIGHTEDAnonymous ymCyFqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Limjoco v. Intestate Estate of Fragante 80 Phil 776Document9 paginiLimjoco v. Intestate Estate of Fragante 80 Phil 776Anonymous ymCyFqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Saludo V American ExpressDocument12 paginiSaludo V American ExpressKevs De EgurrolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hilado Vs CADocument8 paginiHilado Vs CAKevs De EgurrolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Villamor V CADocument21 paginiVillamor V CAAnonymous ymCyFqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gabatan Vs CADocument12 paginiGabatan Vs CAKevs De EgurrolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Specpro Fule V CADocument10 paginiSpecpro Fule V CAPat CostalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ventura v. VenturaDocument7 paginiVentura v. VenturaBarrrMaidenÎncă nu există evaluări

- 115550-2001-Yap - Jr. - v. - Court - of - Appeals20160215-374-Sk309l PDFDocument10 pagini115550-2001-Yap - Jr. - v. - Court - of - Appeals20160215-374-Sk309l PDFleafyedgeÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Re Eusebio V Eusebio PDFDocument6 paginiIn Re Eusebio V Eusebio PDFAnonymous ymCyFqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondents Jose Y. Torres G. D. Demaisip C. A. DabalusDocument4 paginiPetitioner Vs Vs Respondents Jose Y. Torres G. D. Demaisip C. A. DabalusKier Christian Montuerto InventoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5 Marcos - v. - Manglapus20160210-9561-4ya8dc PDFDocument35 pagini5 Marcos - v. - Manglapus20160210-9561-4ya8dc PDFSheba EspinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- People v. FerrerDocument26 paginiPeople v. FerrerKenny BesarioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Misolas v. PangaDocument14 paginiMisolas v. PangaAnonymous ymCyFqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Irs Letter 2 - Internal Revenue Service - Notary PublicDocument21 paginiIrs Letter 2 - Internal Revenue Service - Notary PublicAQUA KENYATTEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pertanggungjawaban Hukum Praktik Tukang Gigi Yang Melebihi Wewenangnya Devi Dharmawan, Ivonne JonathanDocument9 paginiPertanggungjawaban Hukum Praktik Tukang Gigi Yang Melebihi Wewenangnya Devi Dharmawan, Ivonne Jonathanboooow92Încă nu există evaluări

- Inductees Administrators Moral 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1: Teachers' AnswersDocument5 paginiInductees Administrators Moral 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1: Teachers' AnswersWilliam BuquiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- SakubaDocument1 paginăSakubaSwathy Chandran PillaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consti2 Digests S9-13 JReyesDocument60 paginiConsti2 Digests S9-13 JReyesJerickson A. ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dus2052 e - Geneva Convention 3Document38 paginiDus2052 e - Geneva Convention 3chanjunshen_rmcÎncă nu există evaluări

- City of Albuquerque Ethics Complaint: Roxanna Meyers Improper InfluenceDocument2 paginiCity of Albuquerque Ethics Complaint: Roxanna Meyers Improper InfluencePat DavisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Civil Society Definition and Nature of Civil SocietyDocument3 paginiCivil Society Definition and Nature of Civil Society295Sangita PradhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eusebio Gonzales V PCIBDocument12 paginiEusebio Gonzales V PCIBJewel Ivy Balabag DumapiasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Digest: Compania Maritama V CADocument3 paginiCase Digest: Compania Maritama V CAChrys BarcenaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CCAL's Lex Populi: Centre For Constitutional and Administrative LawDocument33 paginiCCAL's Lex Populi: Centre For Constitutional and Administrative LawAnkit ChauhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vol - CXX-No .99 1 3 PDFDocument60 paginiVol - CXX-No .99 1 3 PDFAdnan AdamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Work ReviewerDocument37 paginiSocial Work Reviewerali namla98% (41)

- Waller Couny Jail Review December 2018Document1 paginăWaller Couny Jail Review December 2018National Content DeskÎncă nu există evaluări

- Form No. 1 - Articles of Partnership General Partnership Philippines Legal FormDocument3 paginiForm No. 1 - Articles of Partnership General Partnership Philippines Legal Formgodbwdye3100% (1)

- Eliot 3 Voices of PoetryDocument7 paginiEliot 3 Voices of PoetryAryan N. HassanÎncă nu există evaluări

- WatteauDocument4 paginiWatteauArshad AuleearÎncă nu există evaluări

- Suntay III v. Cojuangco-Suntay, G.R. No. 183053, 16 June 2010Document4 paginiSuntay III v. Cojuangco-Suntay, G.R. No. 183053, 16 June 2010Jem PagantianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guidelines For Facilitating Pro Bono Legal Services in Immigration Court (March 3, 2008)Document6 paginiGuidelines For Facilitating Pro Bono Legal Services in Immigration Court (March 3, 2008)J CoxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Danielle ImbembaDocument10 paginiDanielle ImbembaJeannie AlexandraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bryan T. Nelson v. Wayne Kline and Matthew Cunningham, 242 F.3d 33, 1st Cir. (2001)Document3 paginiBryan T. Nelson v. Wayne Kline and Matthew Cunningham, 242 F.3d 33, 1st Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Joshua Moa Between Company StudentDocument4 paginiJoshua Moa Between Company StudenterljoshuacorderopadelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petitioners vs. vs. Respondents Salonga, Ordonez, Yap, Parlade & Associates Marvin J Mirasol Arturo H Villanueva, JRDocument12 paginiPetitioners vs. vs. Respondents Salonga, Ordonez, Yap, Parlade & Associates Marvin J Mirasol Arturo H Villanueva, JRmenggayubeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cases 0Document1.150 paginiCases 0Taga BukidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Virginia Law Enforcement Accredidation Manual, 8th Edition (Standard Policies)Document56 paginiVirginia Law Enforcement Accredidation Manual, 8th Edition (Standard Policies)OpenOversightVA.orgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Boysaw V Interphil Promotions, 148 SCRA 364 (1987)Document2 paginiBoysaw V Interphil Promotions, 148 SCRA 364 (1987)Faye Cience BoholÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interim Report-2017!12!02 CD5 Committe Rulings On Buchanan AppealDocument13 paginiInterim Report-2017!12!02 CD5 Committe Rulings On Buchanan AppealTBEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nevada Reports 1961 (77 Nev.) PDFDocument409 paginiNevada Reports 1961 (77 Nev.) PDFthadzigsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fundamentals of Contract Law: Dr. V.K. Unni Public Policy & Management Group Indian Institute of Management CalcuttaDocument44 paginiFundamentals of Contract Law: Dr. V.K. Unni Public Policy & Management Group Indian Institute of Management CalcuttaPadmavathy DhillonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chanakya National Law University: The Final Draft For The Fulfilment of Project of Property Law On "Collusive Gifts"Document18 paginiChanakya National Law University: The Final Draft For The Fulfilment of Project of Property Law On "Collusive Gifts"Harshit GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări