Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

430-Article Text-1983-1-10-20190925

Încărcat de

lingamkumarDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

430-Article Text-1983-1-10-20190925

Încărcat de

lingamkumarDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Vol. 150, No.

3 · Research article

Detached islands:

Artificial islands as adaptation

DIE ERDE challenges in the making

Journal of the

Geographical Society

of Berlin

Michelle E. Portman

Associate Professor, Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning, Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Kiryat HaTechnion, Haifa, Israel, 32000

mep@technion.ac.il

Manuscript submitted: 23 January 2019 / Accepted for publication: 28 July 2019 / Published online: 25 September 2019

Abstract

There is surprisingly little information and concern within academic literature in the field of coastal or marine plan-

ning and management related to the issue of artificial islands. This is particularly noteworthy considering the climate

change phenomenon, vis á vis sea-level rise, the urgent need for adaptation, efforts aiming for sustainable use of coastal

areas, and the recent focus in academic circles on marine spatial planning. Most literature (including grey literature) on

artificial islands appears in the engineering and geology disciplines and is focused on energy extraction, i.e., oil and gas.

Yet some coastal nations are intent on solving problems of lack of space and other resource shortages through construc-

tion of near-shore artificial islands for myriad uses, including commercial, residential and transportation infrastruc-

ture. This paper presents a limited review of the policy literature about planning and construction of artificial islands.

It reflects what repercussions artificial islands portend for marine conservation, sustainability and, most importantly,

how climate change adaptation is highlighted or neglected in spatial solutions addressed by the building of nearshore

artificial islands. The Israeli situation, where tenders have been recently published calling for planning and building of

islands in the Mediterranean Sea, serves as an example.

Zusammenfassung

In der Literatur zur Küsten- oder Meeresplanung gibt es überraschend wenig Informationen über künstlich auf-

geschüttete Inseln. Dies ist insbesondere bemerkenswert im Kontext eines sich wandelnden Klimas, dem ein-

hergehenden Meeresspiegelanstieg und der dringenden Notwendigkeit der Anpassung, sowie der Bemühungen

um eine nachhaltige Nutzung der Küstengebiete und der jüngsten Konzentration in akademischen Kreisen auf

maritime Raumordnung. Der überwiegende Teil der Literatur (einschließlich grauer Literatur) über künstlich

aufgeschüttete Inseln erscheint in den Gebieten Ingenieurswesen und Geologie und konzentriert sich auf die

Energiegewinnung von beispielsweise Öl und Gas. Weiterhin gibt es einige Küstenstaaten, die entschlossen sind,

Probleme wie Platzmangel und Ressourcenknappheit durch den Bau und die Nutzung (Handel-, Wohn- und Ver-

kehrsinfrastruktur) von küstennahen, künstlich aufgeschütteten Inseln zu lösen. Diese Studie gibt einen Über-

blick über die einschlägige Fachliteratur zur Planung und Realisierung von künstlichen Inseln. Es werden die

Auswirkungen von künstlichen Inseln auf die Nachhaltigkeit von marinen Ökosystemen diskutiert und analy-

siert, ob Klimaanpassungen in räumlichen Lösungen beim Bau der Inseln integriert werden. Ein aktuelles Fall-

beispiel ist Israel, wo kürzlich die Planung und der Bau von Inseln im Mittelmeer ausgeschrieben wurde.

Keywords ocean sprawl, artificial islands, Mediterranean Sea, sea reclamation, offshore islands

Michelle E. Portman 2019: Detached islands: Artificial islands as adaptation challenges in the making. – DIE ERDE 150

(3): 158-168

DOI:10.12854/erde-2019-430

158 DIE ERDE · Vol. 150 · 3/2019

Detached islands: Artificial islands as adaptation challenges in the making

1. Introduction about how they affect ecosystems services related

to climate change mitigation. The latter is a type of

Despite significant research on sea level rise (SLR) feedback effect, described by Harte (2010) whereas

and other coastal shoreline change phenomena (e.g., rising temperatures bring about the need for actions

accelerated erosion) related to the effects of climate that intensify and accelerate heating of the globe even

change, there seems to be surprisingly little concern further. With regard to changes in the coastal zone,

and interest in how these effects might be connected because erosion and rising sea levels have reduced

to the topic of artificial offshore islands. In general, available shorelines, new shorelines are constructed

within the academic literature (as opposed to pro- on new offshore islands – a type of artificial produc-

fessional “greyˮ literature), there is a dearth of pub- tion of space. However, at the same time the areas con-

lications on the subject of artificial islands. A cursory structed do away with the ocean-water resources that

search in EBSCOhost (“Environment completeˮ) data- would otherwise serve as sinks of carbon sequestra-

base conducted on 16 August 2018 using the words tion, through for example, absorption of CO2 by car-

“artificial islandsˮ searched for within abstracts, re- bon sequestration.

sulted in 141 publications, many from the engineering

field; a same-date search using the terms “artificial Thus a clarifying of the potential detrimental effects

islands” together with “environmental impactsˮ in ab- of detached islands is in order. From an urban plan-

stracts, resulted in only three sources. ning or environmental planning perspective, such a

review needs to go well beyond impacts on the eco-

Within the growing body of literature on climate logical function and the importance of the seas for cli-

change, many publications focus on increasing prob- mate regulation and stabilization. It needs to include

lems of loss of land area by erosion and inundation the impacts on society resulting from the maintenance

(Douglas et al. 2012; Katz and Mushkin 2013; Seme- of such structures, the financial strain on budgets, as

oshenkova and Newton 2015) and solving those prob- well as impacts on existing spatial conditions such as

lems (e.g. Lister and Muk-Pavic 2015; Zviely et al. 2015). urban edges, accepted jurisdictional boundaries, and

It seems that these same issues should be of concern impacts on stable oceanographic conditions (e.g., cur-

when considering the construction of offshore artifi- rents, temperature and salinity gradients, upwelling,

cial islands. Yet there is a disconnect in the public dis- etc.), even regardless of climate change trends.

course about offshore islands in the current era punc-

tuated by climate change. Problems to be encountered The detrimental possibilities related to constructed

during the construction and maintenance of offshore offshore structures have led to the use of new term:

islands (e.g., rising sea levels, frequent and intense “ocean sprawlˮ (Bishop et al. 2017). Like urban sprawl

sea storms, etc.) seem to be missing from the climate on land, with its negative consequences and connota-

change research and literature, therefore, both liter- tions (Randolph 2011), short- and long-term impacts

ally from their attendant mainland, and figuratively, of artificial islands as well as proximate and distanced

based on the discourse, such islands are “detachedˮ. spatial effects, must be weighed in relation to any

possible advantages. Other issues are cost, financial

One of these examples involves discussions among and otherwise. Due to changing conditions and other

planners in Israel about the potential of offshore is- challenges that are part and parcel of the dynamic

lands to serve as a solution for increasing building nearshore environment, construction costs would

and population densities in the country. While there likely be lower than maintenance costs over time es-

is a significant amount of interest in constructing pecially under the current changing, uncertain and

offshore artificial islands in Israelʼs Mediterranean more erratic climate regime.

ocean space, such as a recommendation to consider

the building of nearshore islands for solving infra- This paper first of all describes and clarifies what is

structure needs as mentioned in the Technionʼs Israel meant by “artificial islandsˮ. Once the term is clear,

Marine Plan (Technion Marine Plan Integrating Team the scope of such islands is addressed. These effects

2015), rarely is any connection made to the effects of are viewed in relation to work on adaptation to cli-

climate change in this regard. mate change, highlighting a dissonance. The second

part of this paper focuses on the Israeli case; it cov-

Certainly there are reasons for concern about how ers recent initiatives that strongly advocate the build-

islands might be effected by climate change and also ing of artificial islands along Israelʼs Mediterranean

DIE ERDE · Vol. 150 · 3/2019 159

Detached islands: Artificial islands as adaptation challenges in the making

shoreline. By bringing the two parts of the paper to- The most logical place to start with for a definition of

gether in the discussion, we see that on the one hand, what constitutes an island, is the UN Convention on

proponents are pushing ahead with islands to solve the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). According to UNCLOS

planning problems. On the other hand, challenges, (UN General Assembly 1982), an island is: “a natural-

including those related to climate change adaptation ly formed area of land, surrounded by water, which

measures could be significant (see Zviely et al. 2015). is above water at high tide.” If one adds “artificialˮ

This paper concludes with some speculation as to why to this definition: “caused or produced by a human”

there is such a “disconnectˮ between efforts to build (Merriam-Webster 2003), many structures, masses

offshore artificial islands and efforts to adapt to cli- and even objects, could be included. The first place

mate change along coasts in the Israeli context. “artificial islands” is mentioned in UNCLOS relates to

ports (Part II, §2, Article 11): Off-shore installations

and artificial islands shall not be considered as per-

2. Artificial islands manent “harbour” works. Most importantly, UNCLOS

establishes in Article 56, rights, jurisdiction and du-

2.1 What are “artificial islandsˮ? ties of the coastal State in the exclusive economic zone

(EEZ) with regards to the establishment and use of ar-

The term “artificial islandˮ can be ambiguous. For cen- tificial islands, installations and structures.

turies, coastal development has included filling and

land reclamation for human purposes. As far back as While UNCLOS (Article 60) establishes clearly that

during pre-historic times, hunter-gathers construct- coastal states have the exclusive right to construct,

ed “gardensˮ in the low intertidal areas of coasts, authorize and regulate the construction, operation

expanding and maintaining the area for clams to live and use of artificial islands, such artificial features do

and be harvested that consisted of human-made par- not have the status of islands (e.g., for example affect-

tially submerged rock-walls and terraces (Rick and ing the delimitation of the territorial sea, the EEZ or

Erlandson 2009). Could these be called islands? They the continental shelf). However, this has not stopped

were areas designed for human use but it is unclear China from claiming that massive land reclamation

whether these early ancient activities constituted is- projects in the Spratly Islands area of South China

lands per se. As other examples, are today‘s detached Sea1 around rocky outcrops (previously used only to

breakwaters types of islands? Are polders, built cen- shelter fishermen) are sufficient to change the status

turies ago, but still maintained today in the Nether- of features for extending Chinese jurisdiction and ac-

lands (Diamond 2005: 519), also types of artificial “is- cess to important resources, including usable space.

lands” of human activity in what used to be sea? Chinaʼs claims vis á vis the Philippines, the adjacent

coastal state, were decided by the International Tri-

Certainly over the course of human history, protective bunal on the Law of the Sea. In any case, Chinaʼs mas-

structures, from barrier islands to rock piles, are in es- sive island-building project, which began after the

sence artificial structures promoted and constructed Philippinesʼ initiation of UNCLOS Annex VII proceed-

as a means of generating space, protecting shorelines ings against China in January 2013, created more than

from wave and storm damage and supporting hu- 12.8 million square meters of new land around what

man access to the deeper areas of the sea. Chee et al.‘s the Tribunal determined to be “low-tide elevations”,

(2017) informative paper describes the massive land an action that has engendered international atten-

reclamation efforts around Penang, Malaysia as an ex- tion far beyond the maritime community (Davenport

ample of what is common now in Asia and the Middle 2018).

East and what the authors depict as a “global conser-

vation issue”. The study includes many different types

of “ocean sprawl” as they call it, from the building of 2.2 What are the environmental effects of such is-

seawalls, rock armouring, breakwaters and marinas, lands?

to the “construction of whole new islands”. So, how can

the construction of artificial islands be distinguished Generally speaking, effects of artificial islands on the

from varied types of age-old practices designed to en- marine environment encompass just about every im-

able humans to use the sea area? pact imaginable. They will, in many cases, adversely

affect humans and flora and fauna of the marine and

terrestrial environments (Holon et al. 2018). Most

160 DIE ERDE · Vol. 150 · 3/2019

Detached islands: Artificial islands as adaptation challenges in the making

of what is known regarding expected impacts to the Chee et al. (2017) claim that eco-engineering and ad-

marine environment before a detached island is built, aptation management can offset some of these im-

is based on modelling. As an example, Wang et al.‘s pacts. However, in the same study, it is pointed out

(2013) study used a two-dimensional hydrodynamic that not only the decimation of seagrass beds will oc-

model applied on the basis of the characteristics of the cur in Penang, Malaysia therefore leading to reduction

tides, currents, waves, and sediments in the Jinzhou of habitat for a large variety of marine organisms that

Bay, China. The purpose was to compare layouts for are essential to ecosystem function, but livelihoods

an insular (detached) artificial island to be used as an will be negatively affected as tourism and educa-

airport compared to a peninsular scheme. Expected tion values are damaged. The seagrass beds provide

effects were registered on hydrodynamics, morpho- habitat, feeding and breeding areas for myriad spe-

logical evolution of the coastline, water pollution, and cies including fan shells, sea cucumbers, razor clams,

biological resource loss, thus giving an indication of sponges, seas anemones, octopuses and cockles. Chee

what can be expected for most island layouts. et al. (2017) advocates applying eco-engineering so-

lutions used for shorelines (for example, those pro-

In addition, aesthetics will also be involved, such as moted by Firth et al. (2016)), to larger-scale artificial

those that have determined the fate of offshore wind islands or adopting a “hybrid approach”, that includes

farm construction (see Portman et al. 2009), although the building of shellfish reefs in combination with

it is debatable whether aesthetic impacts are environ- other valuable habitats like mangroves on the edges

mental or more socio-economic. They do fall under of artificial islands. Policies that accompany approv-

the category of ecosystem services, as aesthetics are als of artificial island construction could require re-

cultural services valued by humans, just as are bath- habilitation of destroyed sea grass beds, the addition

ing beaches and other shore area amenities. of reef balls and oyster castles that enhance fisheries,

using artificial wetlands (presumably on and around

Offshore current flow will change. Temperature and the islands) that can treat anthropogenic discharge.

salinity, which are the main determinates of envi- The problem is that we know that implementation of

ronmental conditions in submerged coastal environ- environmentally friendly practices often lags behind

ments, will change as a result and this is to say noth- intentions, especially in developing nations and those

ing yet about the physical impact of anything that is where capacity, including adaptive capacity to deal

constructed on the sea floor. Even if the islands are with climate change, is challenged.

more like floating platforms, there will be effects

from shading within the water column and of course, At a time when so much effort is being put into improv-

any human activities on these platforms (or islands) ing the marine environment, and in protecting marine

will likely generate waste adding to the existing deba- ecosystem function and biodiversity, the building of

cle of marine litter and pollution. Some of these effects artificial islands seems counterproductive, at least

can, of course, be mitigated, but at significant cost. from a strictly environmental perspective. Yet, in

countries trying to meet the demand of burgeoning

The construction of artificial islands has already re- population growth and dwindling resources, espe-

sulted in devastating environmental consequences cially sources of energy (Pisacane et al. 2018; Portman

in the semi-enclosed sea of the Persian Gulf, part of 2014), the idea of building artificial islands is always

a semi-enclosed sea along the coasts of Dubai. The on the table.

dredging of sand has led to the restriction and change

of currents, turbidity and extreme damage to marine

habitats (Moussavi and Aghaei 2013). Some effects are 2.3 Artificial islands in Israel

known, or can be estimated, from work done on track-

ing land reclamation efforts using remote sensing, Michael Bort, a professor of architecture and urban

such as those conducted to determine the extent of planning, has been a recent outspoken advocate of

jurisdictional claims, whether these be legal or sanc- building offshore islands in Israel‘s Mediterranean

tioned internationally or not (Davenport 2018). Tur- Sea. In an article published in a prominent geographic

bidity caused by island construction and measured journal (in Hebrew), he laid out his plan, dubbed “the

using satellite imagery that shows the appearance of Blue Corridor Visionˮ, for such islands. He claims that

plumes, signifies extreme threats to coral reef com- Israelʼs burgeoning population, limited land area and

munities (Barnes and Hu 2016). growing infrastructure needs, leads planners not to

DIE ERDE · Vol. 150 · 3/2019 161

Detached islands: Artificial islands as adaptation challenges in the making

doubt whether such islands should be constructed, but minimal distance from the shore (> 7 km) mostly to

rather to ponder the questions of when they should be avoid aesthetic impacts on views from land.

constructed. He contends that all types of urban land

uses should be built on islands. For the marine area Perhaps more importantly, the TIMP (Technion Ma-

around the seaside city of Haifa alone, he posits that rine Plan Integrating Team 2015: 7-8) comes across as

as much as 25 square kilometers is needed for “ur- reiterating past conclusions that had been arrived at

ban developmentˮ purposes including housing, with by the Israeli government, and planning community.A

approximately 18 square kilometers additional area policy paper on artificial islands adopted by the Na-

needed for infrastructure and industry (Bort 2009). tional Planning and Building Board in 2007 pointed to

a strong preference for the creation of small islands,

Although Bortʼs article was written a decade ago, several thousand square meters in size, for infra-

and he has been promoting his ideas with consider- structure facility clusters – power stations, a liquified

able success ever since, the idea of building artificial natural gas terminal and desalination plants. National

islands in Israel has been around for quite some time. Outline Plan 37H, approved about the time the TIMP

Artificial islands were first considered in the 1970s was completed, designated for the first time two large

with conceptual planning ideas being extensively offshore infrastructure areas at distances of 7-10 km

evaluated in the 1990s. At that time around 6 million from the shore. These areas would be designed to

NIS (equal to approximately 1.4 million Euros today) receive and treat natural gas from nearby drilling/

were allocated by the government to research differ- extraction sites and their siting would include accom-

ent options that would be relevant for the Israeli con- panying pipeline corridors from the facilities to the

text. shore.

During the years 2005-2007, the Israeli National Plan- Although recommending the consideration of such

ning Authority called for the preparation of a policy offshore islands, the TIMP lists various nefarious im-

document on the subject that addressed the planning pacts of construction of islands at distances of less

of such islands. From among the recommendations than 7 km from the shore: e.g., the blockage of the

presented by the experts hired by the government northwards transport of sediments and sand along

following this call, the National Planning Authority the coast; shortages of fill material in addition to

adopted the following points: 1) land uses on islands great uncertainty regarding impacts and even seis-

should be restricted to infrastructure alone; 2) exten- mic instabilities that may impact, and be impacted

sive evaluation, focusing on environmental and eco- by, such islands. In addition to listing these impacts,

nomic issues should proceed any detailed planning; 3) and raising questions with regard to the viability of

an intergovernmental task force would be created to constructing offshore islands, the TIMP suggests that

lead the evaluation process; and 4) recommendations they be sensitively and sustainably developed. How-

from the evaluation would be brought before the Na- ever, beyond declaring that “tools for effective social-

tional Planning Authority for discussion and approval. environmental-economic assessment of the balance

between terrestrial and marine development” be de-

The recently completed Technion Israel Marine Plan veloped, the operational meaning of such conditions is

(TIMP) (Technion Marine Plan Integrating Team 2015: not clear. At the same time, the Israel Marine Plan be-

34-36) addresses the idea of artificial islands with ing developed by the government of Israelʼs Planning

caution and concern, yet with underlying support for Authority, currently under the auspices of the Minis-

the concept. Without identification of particular lo- try of Finance, has been more supportive of the idea

cations for these islands, the TIMP recommends that of constructing offshore artificial islands in Israelʼs

artificial islands be considered for the siting of infra- Mediterranean marine space than the TIMP.

structures to serve the burgeoning population in an

attempt to solve the lack of such areas on land. Some While the Technionʼs Israel Marine Plan clearly does

caveats mentioned in the TIMP are that such infra- not recommend considering development of the ma-

structure centers, whose detailed makeup (floating rine space for general urban land uses beyond infra-

platforms, or pile supported, etc.) and proposed loca- structure, at least “in the near future” and the Min-

tion is unspecified by the plan, could be approved only istry of Financeʼs Planning Authority supports their

if they do not require constructed connections to land consideration, Israelʼs environmental community

via causeways or bridges. Also specified is a required has articulated an adversarial position to them. As

162 DIE ERDE · Vol. 150 · 3/2019

Detached islands: Artificial islands as adaptation challenges in the making

a precursor to a workshop (with approximately 100 organisms. There would also be impacts during the

attendees) held on 1 July 2018 on the subject of ar- construction phase, including elevated turbidity and

tificial offshore islands, a number of environmental noise levels among others (personal communica-

organizations published a position paper against the tion3). Other general news articles have also sounded

development of offshore artificial islands (although the alarm regarding impacts to the health of marine

they are willing to support some forms of offshore and coastal ecosystems from the existence of new ar-

platforms). Since this time, numerous forums have tificial islands off the coasts of Dubai and in the South

presented, discussed, considered and adopted resolu- China Sea (e.g. Cressey 2011; Ives 2016; Poole 2009).

tions regarding the construction of offshore islands,

most recently in the Fall 2018 at a workshop organ- For the most part, the possibility of constructing arti-

ized by the Economic Committee of the Israel Parlia- ficial islands off the Mediterranean Sea coast of Israel

ment (Knesset). This followed the Ministry of Trans- has been addressed conceptually, even though as time

port and Road Safety publication of tenders for the goes on more and more effort is being put into feasi-

feasibility study for construction of artificial islands bility assessment of such projects by various entities.

in Israelʼs Mediterranean marine space for an airport These include, for the most part, various government

and “other uses” (Ministry of Transport and Road ministries, academic institutions and the business

Safety 2017). The publication of the environmental sector. Even though most efforts are aimed at building

NGOsʼ position paper was headed by the Society for infrastructure on such islands, for example for energy

the Protection of the Nature in Israel (SPNI), the Is- production or for desalination and for storage of sub-

rael Union of Environmental Defense (in Hebrew: stances needed to be stored at some distance from the

Adam, Teva vʼ Din) and Tzalul; the latter organization populated coast, Israelʼs housing shortage fueled by

focuses almost exclusively on environmental advoca- high reproduction rates and immigration are factors

cy related to marine, coastal and water policy issues. leading to the country‘s general “turning to the sea”

Their position paper voices concerns about the need (Teff-Seker et al. 2019). By 2035 the country‘s popula-

for excessive amounts of sand (causing shortages) and tion is expected to reach 11.4 million people, a 25%

distributional challenges of sand use, islands becom- growth in population from 2015 (CBS 2018); there is

ing vectors of invasive and alien species (both the is- no doubt that population growth rates will be a factor

lands themselves and sand sources), negative effects in the consideration of offshore artificial island plan-

on the aesthetics of the coastal and marine landscape, ning.

decreasing marine water quality between the islands

and the mainland, acceleration of coastal erosion due

to the blockage of natural sediment transport and as- 3. Discussion – Why is there a dissonance?

sociated beach-narrowing and coastal cliff collapse

(see also Portman 2018). While the position paper The final theoretical contribution of this paper sug-

points out these derogative effects, the paper also gests a dissonance, and reasons for it, between arti-

offers some solutions (or rather recommends condi- ficial islands and adaptation strategies. While it is

tions) for constructing islands in a way that would be clear that rising sea levels will have overwhelmingly

least impactful to the sea; for example, through the negative impacts on coastal communities and much

use of preferred floating platforms or filled floating research has looked at these effects, especially at how

cartridges.2 Therefore, the document, while clearly SLR affects storm-induced flooding and erosion (e.g.

opposing many aspects of artificial islands construc- for Israel: Zviely et al. 2015; Bitan and Zviely 2018).

tion, comes across as compromising. There is even new evidence that SLR increases both

the frequency and the intensity of tsunami-induced

In addition to numerous undesirable impacts articu- flooding (Li et al. 2018). Intuitively these impacts af-

lated by marine and environmental conservation fecting coastal infrastructures and communities will

NGOs, the international engineering community has be severe on artificial islands, yet the connection is

pointed out the detrimental impacts (and challenges) rarely made.

of offshore artificial islands. In general, islands cre-

ate “shadow zones” where wave and current action There are, therefore, basically two ways to look at

would be reduced with the associated impacts on the relationship between artificial islands and cli-

water quality (i.e., stagnation), sediment transport mate change. One more unique view, considers the

(i.e., deposition) and marine and benthic habitat and contribution of such islands to the acceleration of cli-

DIE ERDE · Vol. 150 · 3/2019 163

Detached islands: Artificial islands as adaptation challenges in the making

mate change. Artificial islands do away with areas of So far, there are no artificial islands built in the Medi-

the sea that could serve as carbon sinks and climate terranean and Israel‘s conceptual plans for them em-

regulators and they have great potential to become body a serious precedent. With regard to islands in

additional elements that heat the globeʼs surface. The the Mediterranean, of which there are many4, only

second view considers the adaptation challenge of ar- very specific (mostly case study) research has been

tificial islands; they increase human vulnerability in conducted as part of climate change assessments ei-

the face of climate change. Here, I focus on the second ther on the vulnerability of islands (e.g. Navarra and

aspect of the relationship. Risks from climate change Tubiana 2013b) or on the contributions to greenhouse

effects will be intensified as human elements, wheth- gas emissions. With regard to the latter, one of the few

er devoid of human presence or not, are put in climate- studies connecting Mediterranean islands and climate

vulnerable locations, i.e., directly in harmʼs way. change in general, were sensitivity runs performed by

Kallos et al. (2007). The study revealed the role of the

From this view, the Mediterranean area, in particu- Aegean Sea islands as chimneys transferring polluted

lar, is quite vulnerable to climate change effects. Un- air masses from the marine boundary layer to the free

der current emission scenarios, the Mediterranean is troposphere (Navarra and Tubiana 2013a). Effects of

and will be increasingly affected by climate change SLR on well-being and sustainability of coastal area

in the course of the twenty first century, with severe economies of both islands (Tzoraki et al. 2018) and

impacts on the environment and human welfare (IPCC mainland, including Israel (e.g. Bitan and Zviely 2018),

2014). The traditional economic activities that have have been conducted, showing significant impacts.

been guaranteeing the livelihood of coastal communi-

ties for centuries are all at risk, in particular agricul- So why is there this disconnect? On the one hand,

ture, fisheries and tourism (Pisacane et al. 2018). there is significant literature and knowledge about

what changes are likely to occur in Israel from climate

The area of Alexandria, Egypt, relatively close to the change and these have been known for some time

shores of Israel and part of the Nile Delta littoral cell, (Paz and Kidar 2007); on the other hand, the planning

was used as a coastal case study for an important as- community and the government seems to be working

sessment of the effects of climate change in the Medi- full-steam-ahead to allow artificial islands to serve as

terranean Sea conducted as part of the Integrated a solution for many resource shortages experienced

Research Project – Climate Change and Impact Re- in the country, particularly that of space. Clearly the

search (CIRCE): Mediterranean Environment. Since building of offshore artificial islands has philosophi-

the building of the Aswan High Dam in 1964 there has cal, social and environmental health and well-being

been a rapid reduction in the amount of sediment ac- implications that require more research, discussion

creted, leading to significant and rapid changes along and public debate, yet planning is underway. Two po-

the northern shoreline at the delta‘s mouth. The most tential hypotheses for the lack of caution and hesita-

vulnerable areas in the West Nile Delta are the low ly- tion can be conjectured. The first is that the private

ing districts of Alexandria, the Behaira governorates, professional planning community lacks strong con-

and between Abu Qir Bay and the Rosetta promontory nections to the environmental scientific community.

(Navarra and Tubiana 2013c), however, ultimately, as The second is that it is well known that short-term

part of the same littoral cell, Israel‘s coastline is also fixes are the purview of politicians who in many cases

affected (Portman 2012; Portman 2018). These areas lead the professional community down a risky path of

are highly vulnerable to the combined hazards of sea- short-term planning.

level rise and heat extremes which increase the risk of

saline intrusion, flooding and inundation of prime ag- Integration would be a solution to the first issue –

ricultural land and industrial facilities, and insurance that related to the challenge of linking policy to sci-

losses due to storm damage and coastal flooding. For ence. Much has been written about the advantages to

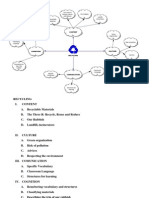

example, the low-lying deltaic areas of the Nile and integration of this kind (see Fig. 1). The second issue

Ebro rivers (two of the CIRCE coastal case-study loca- must be addressed through managing risk within

tions) are subject to rapid rates of subsidence and are the framework of adaptation strategies (see CRC-URI

particularly vulnerable to changes in mean sea level 2009). The Israeli government published Decision No.

or wave storminess (Navarra and Tubiana 2013c). 4079 on 29 July 2018 entitled “Israelʼs Preparedness

for Climate Change: Implementation of the Recom-

mendations to the Government for National Strategy

164 DIE ERDE · Vol. 150 · 3/2019

Detached islands: Artificial islands as adaptation challenges in the making

and Action Plan”. This decision follows up on two pre- ity can and should be assessed. This means gaining

vious government decisions (nos. 474 and 1504 dated full knowledge about the exposure of a community

25 June 2009 and 14 March 2010, respectively) that to hazards and the consequence of that hazard if it

both called for the preparation of such a national occurs will lead to various perceptions of risk. Yet it

strategy and plan. Unfortunately, it has taken almost is known that risk perception is limited by various

a decade for the follow up to materialize. characteristics inherent to the issue of climate change

(i.e., global, long-term, uncertain) and social-psycho-

On the upside, the Decision 4079 calls for specific ac- logical processes (i.e., media framing, perceptions

tions that will achieve five goals, the first of which is of communicators, dissonance, denial) (Upham et al.

“Reduction of vulnerability...”. A pragmatic step called 2009). In short, these factors have undoubtedly led to

for by the decision is the establishment of a directo- a dissonance, or disconnect, between thinking about

rate – The Directorate for Climate Change Prepared- resource shortage solutions and adaptive strategies

ness – responsible for coordinating between the many simultaneously. Further research and public policy

government ministries (almost 20) what will each be analysis is needed to address what can be done to sur-

required to plan and implement actions supporting mount these obstacles.

the five goals. Since this new decision represents a re-

vival of actions that have been slow in materializing,

it is difficult to predict how the national strategy and 4. Conclusions

plan will influence (or not) planning and construc-

tion of offshore islands. Of note, is that the Ministry The IPCC specifically states regarding islands that

leading the effort towards preparedness for climate the “High ratio of coastal area to land mass will make

change is the Israel Ministry of Environmental Pro- adaptation a significant financial and resource chal-

tection (MoEP), known to be underfunded and under- lenge” (IPCC 2014: 24). Yet some countries, experienc-

staffed. In any case, the MoEP has been instrumental ing resource shortages exacerbated by high rates of

in bringing science to bear on policy in the past and population growth and high standards of living, seek

as such, the current government decision is a hopeful to build artificial islands for myriad human uses in the

one, provided the connection between increasing vul- coastal zones. Israel is one of these countries. Since

nerability and the development of offshore artificial risk is a multiple of vulnerability and the severity of

islands is made. danger, the construction of artificial islands seems to

be detached from the realities of climate change and

therefore a highly risky endeavor.

Despite these issues, when we look at the agendas

promoting artificial island construction along the

Inter-sectoral

Spatial Mediterranean coast of Israel, it seems likely that the

Intergovernmental

Temporal

Public-private construction of some type of offshore islands will take

place in the future. In keeping with what is known

Science-Policy about climate change and its associated risks, much

more research is needed before implementing such

Specific uses Disciplines (fields of inquiry) Jurisdictional boundaries solutions to resource shortages. Ultimately the con-

Institutional authorities Research and policy Landscape units

Stakeholder groups Social and natural science Various scales (e.g., time)

nection of artificial island planning to what is known

Ecological systems (and what will soon be discovered) about climate

change must be made with the understanding that the

Fig. 1 Dimensions of integration generally and for marine

coastal zones of today are not the coastal zones of to-

spatial planning purposes with an emphasis on inte-

grating science and policy. Source: adapted from Port- morrow.

man (2011)

The first step in the development of climate adapta- Notes

tion strategies is the assessment of vulnerability

(CRC-URI 2009; Portman 2016) and these must make 1 There was uncertainty as to the South China Sea features,

use of academic work that has already made this con- namely, whether they are islands above water at high tide

nection (e.g. Zviely et al. 2015). The level of vulnerabil- (Article 121(1)) or low-tide elevations submerged at high

DIE ERDE · Vol. 150 · 3/2019 165

Detached islands: Artificial islands as adaptation challenges in the making

tide but above water at low tide (Article 13), and whether environment

the islands are entitled to the full suite of maritime zones Cressey, E. 2011: Gulf ecology hit by coastal development. –

under UNCLOS or are rocks only entitled to a 12 nm ter- Nature 479 (277), doi:10.1038/479277a

ritorial sea under Article 121 (for explanation of the deci- Davenport, T. 2018: Island-building in the south china sea:

sion, see Davenport (2018). Legality and limits. – Asian Journal of International Law

2 Examples are modular giant triangles that tied together 8 (1): 76-90

make floating mega islands, such as those developed by Diamond, J. 2005: Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or

researchers at the Maritime Research Institute Nether- Succeed. – New York

lands (MARIN). – A video showing a model of a floating Douglas, E., P. Kirshen, M. Paolisso, C. Watson, J. Wiggin, A. En-

mega-island tested in 15m waves is online available at: rici, and M. Ruth 2012: Coastal flooding, climate change

https://www.digitaltrends.com/cool-tech/marin-artificial- and environmental justice: identifying obstacles and in-

island/Accessed 16/9/2019 centives for adaptation in two metropolitan Boston Mas-

3 Personal communication via email on 23 July 2018 with D. sachusetts communities. – Mitigation and Adaptation

Anglin, M.Sc., P. Eng., Baird and Associates Coastal Engi- Strategies for Global Change 17: 537-562

neers Ltd. Firth, L.B., A.M. Knights, D. Bridger, A.J. Evans, N. Mieszkows-

4 The length of the Mediterranean coastline totals about ka, P.J. Moore, N.E. O‘Connor, E.V. Sheehan, R.C. Thompson

46,000 km, of which 19,000 km represent island coast- and S.J. Hawkins 2016: Ocean sprawl: challenges and op-

lines. portunities for biodiversity management in a changing

world. – Oceanography and Marine Biology: an annual

review 54: 193-269

References Harte, J. 2010: Numbers Matter: Human Population as a Dy-

namic Factor in Environment Degradation. – In: Mazor, L.

Barnes, B.B. and C. Hu 2016: Island building in the South (ed.): A Pivotal Moment. – Washington, D.C.: 136-144

China Sea: detection of turbidity plumes and artificial is- Holon, F., G. Marre, V. Parravicini, N. Mouquet, T. Bockel, P.

lands using Landsat and MODIS data. – Scientific Reports Descamp, F. Holon, G. Marre, V. Parravicini, N. Mouquet,

6 (33194): 1-12, doi:10.1038/srep33194 T. Bockel, P. Descamp, A.-S. Tribot, P. Boissery and J. Deter

Bishop, M.J., M. Mayer-Pinto, M., L. Airoldi, L.B. Firth, R.L. Mor- 2018: A predictive model based on multiple coastal an-

ris, L.H. Loke, S.J. Hawkins, L.A. Naylor, R.A. Coleman, S.Y. thropogenic pressures explains the degradation status

Chee and K.A. Dafforn 2017: Effects of ocean sprawl on of a marine ecosystem: Implications for management and

ecological connectivity: impacts and solutions. – Journal conservation. – Biological Conservation 222: 125-135,

of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 492: 7-30, doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2018.04.006

doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2017.01.021 IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) 2014: Cli-

Bitan, M. and D. Zviely 2018: Lost value assessment of bath- mate Change 2014: Summary for policymakers: Impacts,

ing beaches due to sea level rise: a case study of the Medi- Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Secto-

terranean coast of Israel. – Journal of Coastal Conserva- ral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth

tion 18 (1): 1, doi:10.1007/s11852-018-0660-7 Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on

Bort, M. 2009: T‘hee HaYam – The Conceptual Plan for the Climate Change. – In: C.B. Field, V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken,

Marine Alternative for Haifa Development [in Hebrew]. K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L.

– Horizons in Geography (Ofekim b‘Geografia) 73: 42-57 Ebi, Y.O. Estraa, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy,

CBS (Central Bureau of Statistics) 2018: Sources of Popula- S.S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea and L.L. White (eds.). –

tion Growth by Type of Locality, Population Group and Cambridge: 1-32

Religion. – Jerusalem Israel Ministry of Transport and Road Safety 2017: Notice

Chee, S.Y., A.G. Othman, Y.K. Sim, A.N. Mat Adam and L.B. Firth to English News Media, July 2017. – Online available at:

2017: Land reclamation and artificial islands: Walk- https://www.mr.gov.il/officestenders/Pages/officetender.

ing the tightrope between development and conser- aspx?pID=597559

vation. – Global Ecology and Conservation 12: 80-95, Ives, M. 2016: The Rising Toll of China‘s Offshore Island

doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2017.08.005 Land Grab. – Yale Environment 360. Online available at:

CMCC (Fondazione Centro Euro-Mediterraneo sui Cambia- https://e360.yale.edu/features/rising_environmental_

menti Climatici) no date: CIRCE – Climate change and toll_china_artificial – accessed 5/1/2018.

impact research: the Mediterranean environment. – On- Kallos, G., M. Astitha, P. Katsafados and C. Spyrou 2007: Long-

line available at: https://www.cmcc.it/projects/circe- range transport of anthropogenically and naturally

climate-change-and-impact-research-the-mediterranean- produced particulate matter in the Mediterranean and

166 DIE ERDE · Vol. 150 · 3/2019

Detached islands: Artificial islands as adaptation challenges in the making

North Atlantic: current state of knowledge. – Journal of exploratory drilling for oil and gas. – Energy Policy 65:

Applied Meteorology and Climatology 46 (8): 1230-1251, 37-47, doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.10.010

doi:10.1175/JAM2530.1 Portman, M.E. 2016: Current Issues: Coastal Adaptation to

Katz, O. and A. Mushkin 2013: Characteristics of sea-cliff Climate. – In: Portman, M.E. (ed.): Environmental Plan-

erosion induced by a strong winter storm in the eastern ning for Oceans and Coasts: Methods, Tools, Technolo-

Mediterranean. – Quaternary Research 80 (1): 20-32, gies. – Dordrecht: 191-210

doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2013.04.004 Portman, M.E. 2018: Policy Options for Coastal Protection:

Li, L., A.D. Switzer, Y. Wang, C.-H. Chan, Q. Qiu and R. Weiss Integrating Inland Water Management with Coastal Man-

2018: A modest 0.5-m rise in sea level will double the agement for Greater Community Resilience. – Journal of

tsunami hazard in Macau. – Science Advances 4 (8): Water Resources Planning and Management 144 (4):

eaat1180, doi:10.1126/sciadv.aat1180 05018005, doi:10.1061/(ASCE)WR.1943-5452.0000913

Lister, N., and E. Muk-Pavic 2015: Sustainable artificial island Portman, M.E., J.A. Duff, J. Köppel, J. Reisert, and M.E. Higgins

concept for the Republic of Kiribati. – Ocean Engineering 2009: Offshore Wind Energy Development in the Exclu-

98: 78-87, doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2015.01.013 sive Economic Zone: Legal and Policy Supports and Im-

Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary 2003: English Dic- pediments in Germany and the U.S. – Energy Policy 37

tionary, Eleventh Revised Edition. – Springfield (9): 3596-3607, doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2009.04.023

Ministry of Transport and Road Safety 2017, Notice to Eng- Randolph, J. 2011: Environmental Land Use Planning and

lish News Media, July, 2017. – Online availabe at: https:// Management. – Washington DC

w w w.mr.gov.il/officestenders/Pages/officetender. Rick, T.C. and J.M. Erlandson 2009: Coastal Exploitation. – Sci-

aspx?pID=597559 – accessed 7/4/2019. ence 325 (5943): 952-953, doi:10.1126/science.1178539

Moussavi, Z. and A. Aghaei 2013: The Environment, Geopoli- Semeoshenkova, V. and A. Newton 2015: Overview of ero-

tics and Artificial Islands of Dubai in the Persian Gulf. – sion and beach quality issues in three Southern Euro-

Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 81: 311-313, pean countries: Portugal, Spain and Italy. – Ocean and

doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.434 Coastal Management 118 (Part A): 12-21, doi:10.1016/j.

Navarra, A. and L.E. Tubiana, 2013a: Regional Assessment ocecoaman.2015.08.013

of Climate Change in the Mediterranean, 1: Air, Sea and TIMP (Technion Marine Plan Integrating Team) 2015: The Is-

Precipitation and Water. – Dordrecht rael Marine Plan. – Haifa: 7-8, 34-36,. – Online available

Navarra, A. and L.E. Tubiana, 2013b: Regional Assessment at: https://msp-israel.net.technion.ac.il/files/2015/12/

of Climate Change in the Mediterranean, 2: Agriculture, MSP_plan.compressed.pdf

Forests and Ecosystem Services and People. – Dordrecht Teff-Seker, Y., E. Eiran and A. Rubin 2019: Israel’s ‘Turn to the

Navarra, A. and L.E. Tubiana, 2013c: Regional Assessment of Sea’ and its Effect on Regional Policy. – Journal of Israel

Climate Change in the Mediterranean, 3: Case studies. – Affairs: 1-22, doi:10.1080/13537121.2019.1577037

Dordrecht Tzoraki, O., I.N. Monioudi, A.F. Velegrakis, N. Moutafis, G. Pav-

Paz, S. and O. Kidar 2007: Climate Change – Forecast Impacts logeorgatos and D. Kitsiou 2018: Resilience of Touristic

and Predicted Phenomena: Global Background and Israe- Island Beaches Under Sea Level Rise: A Methodological

li Perspective [in Hebrew]. – Haifa Framework. – Coastal Management 46 (2): 78-102, doi:

Pisacane, G., G. Sannino, A. Carillo, M.V. Struglia and S. Bas- 10.1080/08920753.2018.1426376

tianoni 2018: Marine Energy Exploitation in the Mediter- UN General Assembly 1982: Convention on the Law of the

ranean Region: Steps Forward and Challenges. – Fron- Sea, 10 December 1982, entered into force 16 November

tiers in Energy Research 6 (109): 1-17, doi:10.3389/ 1994. – Online available at: https://www.un.org/Depts/

fenrg.2018.00109 los/general_assembly/general_assembly_resolutions.

Poole, E. 2009: The Dubai Palms: Construction and Environ- htm – accessed 4/1/2019.

mental Consquences. Paper presented at the World Envi- Upham, P., L. Whitmarsh, W. Poortinga, K. Purdam, A. Darn-

ronmental and Water Resources Congress. ton, C. McLachlan and P. Devine‐Wright 2009: Public At-

Portman, M.E. 2011: Marine Spatial Planning: Achieving and titudes to Environmental Change: a selective review of

Evaluating Integration. – ICES Journal of Marine Science theory and practice. – Online available at: https://esrc.

68 (10): 2200-2191, doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsr157 ukri.org/files/public-engagement/public-dialogues/

Portman, M.E. 2012: Losing Ground: Mediterranean Shore- full-report-public-attitudes-to-environmental-change/ –

line Change from an Environmental Justice Perspective. accessed 10/09/2019

– Coastal Management 40 (4): 421-441, doi:10.1080/089 USAID (United States Agency for International Development)

20753.2012.692307 2009: Adapting to Coastal Climate Change: A Guidebook

Portman, M.E. 2014: Regulatory capture by default: Offshore for Development Planners. – Washington, D.C. – On-

DIE ERDE · Vol. 150 · 3/2019 167

Detached islands: Artificial islands as adaptation challenges in the making

line available at: https://www.adaptation-undp.org/ Island. – Journal of Environmental Engineering 139 (3):

sites/default/files/downloads/usaid_adapting_to_coast- 438-449, doi:10.1061/(ASCE)EE.1943-7870.0000649

al_climate_change_–_a_guidebook_for_development_ Zviely, D., M. Bitan and D.M. DiSegni 2015: The effect of sea-

planners.pdf – accessed 13/9/2019. level rise in the 21st century on marine structures along

Wang, N., H.-K. Yan, Z.-B. Liu, S.-Q. Tong, T.-L. Yu and C. Liang the Mediterranean coast of Israel: An evaluation of physi-

2013: Effects of Different Layout Schemes on the Marine cal damage and adaptation cost. – Applied Geography 57:

Environment of the Dalian Offshore Reclaimed Airport 154-162, doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.12.007

168 DIE ERDE · Vol. 150 · 3/2019

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Paranoia XP - Gamemaster Screen Booklet - Mandatory Fun Enforcement PackDocument24 paginiParanoia XP - Gamemaster Screen Booklet - Mandatory Fun Enforcement PackStBash100% (3)

- Design and Calculus of Offshore TowersDocument101 paginiDesign and Calculus of Offshore Towerssandhu4140Încă nu există evaluări

- Sch3u Exam Review Ws s2018 PDFDocument4 paginiSch3u Exam Review Ws s2018 PDFwdsfÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accsap 10 VHDDocument94 paginiAccsap 10 VHDMuhammad Javed Gaba100% (2)

- Artificial Islands: January 2016Document13 paginiArtificial Islands: January 2016MohamedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Raspberry Pi 3 and BeagleBone Black For Engineers - UpSkill Learning 124Document124 paginiRaspberry Pi 3 and BeagleBone Black For Engineers - UpSkill Learning 124Dragan IvanovÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moses ManualDocument455 paginiMoses ManualDadypeesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Agathiyar Thaila MuraigalDocument18 paginiAgathiyar Thaila MuraigalVmani Ayyar100% (7)

- FEMA FilterManual 2011Document362 paginiFEMA FilterManual 2011ina_cri100% (1)

- Bolt Action Italian Painting GuideDocument7 paginiBolt Action Italian Painting GuideTirmcdhol100% (2)

- Listening - Homework 2: Brushes 285 RamdhanieDocument4 paginiListening - Homework 2: Brushes 285 RamdhanieBao Tran NguyenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cambios en El Área 2020Document9 paginiCambios en El Área 2020Livia RodríguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sustainability 13 05301 With CoverDocument18 paginiSustainability 13 05301 With CoverNamish ShuklaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Regional Studies in Marine Science: SciencedirectDocument8 paginiRegional Studies in Marine Science: SciencedirectHasna Nurul Muthi'ahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Article Will Ports Become Forts Climate Change Impacts Opportunities and Challenges Terra Et Aqua 122 2Document7 paginiArticle Will Ports Become Forts Climate Change Impacts Opportunities and Challenges Terra Et Aqua 122 2MilySandersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coastal Erosion Research PaperDocument6 paginiCoastal Erosion Research Paperafeawjjwp100% (1)

- Coastal and Estuarine Fine Sediment ProcDocument3 paginiCoastal and Estuarine Fine Sediment ProcNicolas AlbornozÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Vernacular Architecture Structure On Urban Sustainability Case Study: Qeshm Island, IranDocument14 paginiEffects of Vernacular Architecture Structure On Urban Sustainability Case Study: Qeshm Island, IranSneha KalyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Document 1 - 2Document3 paginiDocument 1 - 2SADEQÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Perspect6ive Individual ReportDocument11 paginiGlobal Perspect6ive Individual Reportaiza abbassÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Coastal Engineering and Management - (2Nd Edition) © World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. LTDDocument23 paginiIntroduction To Coastal Engineering and Management - (2Nd Edition) © World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. LTDSon TranÎncă nu există evaluări

- This Item Is The Archived Peer-Reviewed Author-Version ofDocument5 paginiThis Item Is The Archived Peer-Reviewed Author-Version ofKeirl John AsinguaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pressures, Stresses, Shocks and Trends in Estuarine Ecosystems e An Introduction and SynthesisDocument8 paginiPressures, Stresses, Shocks and Trends in Estuarine Ecosystems e An Introduction and SynthesisAgus RomadhonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Memo After ReviewDocument2 paginiMemo After Reviewapi-620167298Încă nu există evaluări

- Hill 2015Document9 paginiHill 2015Trọng HiệpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Memo After Review-1Document4 paginiMemo After Review-1api-620167298Încă nu există evaluări

- Hydraulic and Coastal Structures in International PerspectiveDocument49 paginiHydraulic and Coastal Structures in International PerspectivelollazzoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Utrecht University: Climate Physics Institute For Marine and Atmospheric Research Master ThesisDocument31 paginiUtrecht University: Climate Physics Institute For Marine and Atmospheric Research Master ThesisRizal Kurnia RiskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Vernacular Architecture Structure On Urban Sustainability Case Study: Qeshm Island, IranDocument14 paginiEffects of Vernacular Architecture Structure On Urban Sustainability Case Study: Qeshm Island, IranSneha KalyanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book Reviews: S. VenkateshDocument1 paginăBook Reviews: S. VenkateshAffo AlexÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lupin Fras TissuesDocument38 paginiLupin Fras TissuesMalou SanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literature Review On Coastal ErosionDocument6 paginiLiterature Review On Coastal Erosionaflstjdhs100% (1)

- Adapting Cities For Climate Change The Role of TheDocument20 paginiAdapting Cities For Climate Change The Role of TheAnastasiia Sin'kovaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (I) There Is Evidence of The Thawing of The Poles, Which Is Just A Sample of The GreatDocument3 pagini(I) There Is Evidence of The Thawing of The Poles, Which Is Just A Sample of The GreatStefanyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coastal Landforms Caused by Deposition and ErosionDocument19 paginiCoastal Landforms Caused by Deposition and Erosionesteban duranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parola: A Proposed Community Dike in Jalajala, Rizal Green Engineering, Light Weight ConcreteDocument9 paginiParola: A Proposed Community Dike in Jalajala, Rizal Green Engineering, Light Weight ConcreteFelix, Rysell De LeonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Island Ecology On Biological-Cultural DiversitiesDocument7 paginiIsland Ecology On Biological-Cultural DiversitiesCahayanisa Dwi LestariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global and Planetary ChangeDocument9 paginiGlobal and Planetary Changetasos_rex3139Încă nu există evaluări

- UIS 1 Grydehoj PublicSpaceDocument22 paginiUIS 1 Grydehoj PublicSpaceMafalda CarvalhoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Vernacular Architecture Structure On Urba 2018 Frontiers of ArchiDocument14 paginiEffects of Vernacular Architecture Structure On Urba 2018 Frontiers of ArchiSofia FigueredoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ocean and Coastal Management: Nelson Rangel-Buitrago, Victor N. de Jonge, William NealDocument10 paginiOcean and Coastal Management: Nelson Rangel-Buitrago, Victor N. de Jonge, William NealBaluÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Vernacular Architecture Structure On Urban Sustainability Case Study: Qeshm Island, IranDocument14 paginiEffects of Vernacular Architecture Structure On Urban Sustainability Case Study: Qeshm Island, IranManviÎncă nu există evaluări

- JGR Earth Surface - 2017 - Vitousek - Can Beaches Survive Climate ChangeDocument8 paginiJGR Earth Surface - 2017 - Vitousek - Can Beaches Survive Climate ChangeROHIT AGRAWALÎncă nu există evaluări

- Space Technologies and Climate ChangeDocument4 paginiSpace Technologies and Climate ChangeHamzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fmars 08 674630Document17 paginiFmars 08 674630GodwayneÎncă nu există evaluări

- FormalfinalDocument8 paginiFormalfinalapi-620232040Încă nu există evaluări

- Formal Final With Track ChangesDocument8 paginiFormal Final With Track Changesapi-620232040Încă nu există evaluări

- Energy For Ecology: Colin ManasseDocument10 paginiEnergy For Ecology: Colin ManasseColin ManasseÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Douglas J. Sherman (Ed.) ) Treatise On Geomorpholo (B-Ok - CC)Document448 pagini(Douglas J. Sherman (Ed.) ) Treatise On Geomorpholo (B-Ok - CC)Herman SamuelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Draft SL Rise CoastalDocument21 paginiFinal Draft SL Rise Coastalapi-606503051Încă nu există evaluări

- Fennia 2022 As PublishedDocument15 paginiFennia 2022 As PublishedEdward HuijbensÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adaptacijagradova CvejicTutundzicBobicRadulovicDocument19 paginiAdaptacijagradova CvejicTutundzicBobicRadulovicstratmen.sinisa8966Încă nu există evaluări

- Science of The Total Environment: K.R. Gunawardena, M.J. Wells, T. KershawDocument16 paginiScience of The Total Environment: K.R. Gunawardena, M.J. Wells, T. KershawMarie Cris Gajete MadridÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fox Et Al. - 2016 - You Kill The Dam, You Are Killing A Part of MeDocument12 paginiFox Et Al. - 2016 - You Kill The Dam, You Are Killing A Part of MeFa HimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chap1 IntroductionDocument4 paginiChap1 IntroductionSatya S AtluriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Climate Change Adaptation in Practice Peoples ResDocument19 paginiClimate Change Adaptation in Practice Peoples ResRidho AinurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Meira Thaissa An Assessment On Migration With DignityDocument10 paginiMeira Thaissa An Assessment On Migration With DignityFARIDAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aroucha 2018Document23 paginiAroucha 2018Paulo PinheiroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Frihy 2003Document25 paginiFrihy 2003mijazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oikos - 2019 - Todd - Towards An Urban Marine Ecology Characterizing The Drivers Patterns and Processes of Marine PDFDocument28 paginiOikos - 2019 - Todd - Towards An Urban Marine Ecology Characterizing The Drivers Patterns and Processes of Marine PDFDaniel BermudezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Whence and Whither of Marine Spatial Planning: Revisiting The Social Reconstruction of The Marine Environment in The UKDocument12 paginiThe Whence and Whither of Marine Spatial Planning: Revisiting The Social Reconstruction of The Marine Environment in The UKA. ChengÎncă nu există evaluări

- Awang NDocument10 paginiAwang NJames CowderoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 s2.0 S0964569115000812 MainDocument19 pagini1 s2.0 S0964569115000812 Mainquijanovalo83Încă nu există evaluări

- 1.1 Humans and The Coastal ZoneDocument31 pagini1.1 Humans and The Coastal ZoneRirin lestariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ocean & Coastal Management: M. Sanò, J.A. Jiménez, R. Medina, A. Stanica, A. Sanchez-Arcilla, I. TrumbicDocument8 paginiOcean & Coastal Management: M. Sanò, J.A. Jiménez, R. Medina, A. Stanica, A. Sanchez-Arcilla, I. TrumbicAbdul WadoudÎncă nu există evaluări

- ASSIGNMENT ON ARC Sustainable Arch3Document24 paginiASSIGNMENT ON ARC Sustainable Arch3onyinyechi okorieÎncă nu există evaluări

- BG 16 1657 2019 PDFDocument15 paginiBG 16 1657 2019 PDFAnu ParthaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amphibious Cities: Dissertation 2019Document9 paginiAmphibious Cities: Dissertation 2019Devansh KhareÎncă nu există evaluări

- Floating Houses - Chances and Problems: H. Stopp & P. StrangfeldDocument13 paginiFloating Houses - Chances and Problems: H. Stopp & P. StrangfeldRadhika KhandelwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- FPS Rig Track Pressure Calculation ToolDocument9 paginiFPS Rig Track Pressure Calculation ToollingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indian Concrete CodeDocument25 paginiIndian Concrete CodePiv0terÎncă nu există evaluări

- Optimal Foundation Solution For Storage Terminal in MangaloreDocument4 paginiOptimal Foundation Solution For Storage Terminal in MangalorelingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Column 939Document9 paginiColumn 939lingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Opile PDFDocument2 paginiOpile PDFlingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cantilever Retaining WallDocument5 paginiCantilever Retaining WalllingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stal9781607500315 2280Document4 paginiStal9781607500315 2280lingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Infinite Slope Stability AnalysisDocument1 paginăInfinite Slope Stability AnalysislingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- SCV Recommended PackDocument8 paginiSCV Recommended PacklingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amc PDFDocument1 paginăAmc PDFlingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Receipt PDFDocument1 paginăReceipt PDFlingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- SLOPE ModelingDocument252 paginiSLOPE ModelingSarah Wulan SariÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Investigation On Distressed Concrete Piles by Pit and Their Repair and RetrofittingDocument9 paginiAn Investigation On Distressed Concrete Piles by Pit and Their Repair and RetrofittinglingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 02 GandhiDocument40 pagini02 GandhilingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amc PDFDocument1 paginăAmc PDFlingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Internal ErosionProgressRepDocument10 paginiInternal ErosionProgressReplingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2951Document6 pagini2951lingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design and Performance of A 15m Deep Excavation For A Wagon TipplerDocument5 paginiDesign and Performance of A 15m Deep Excavation For A Wagon TipplerlingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shar NDT BuidingDocument1 paginăShar NDT BuidinglingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Holistic Medicine: Holistic Sexology and Acupressure Through The Vagina (Hippocratic Pelvic Massage)Document15 paginiClinical Holistic Medicine: Holistic Sexology and Acupressure Through The Vagina (Hippocratic Pelvic Massage)lingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shar NDT BuidingDocument1 paginăShar NDT BuidinglingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- BC354 80 Part1 PDFDocument45 paginiBC354 80 Part1 PDFlingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- KCDE Coring in Hole Tools CatalogueDocument80 paginiKCDE Coring in Hole Tools CataloguelingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emeca Pile Joint UserguideDocument16 paginiEmeca Pile Joint UserguideKevin LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of Field Performance of Embankments On Soft Clay Deposit With and Without PVD-improvementDocument23 paginiAnalysis of Field Performance of Embankments On Soft Clay Deposit With and Without PVD-improvementlingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maizer SamplDocument1 paginăMaizer SampllingamkumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ventricular Septal DefectDocument9 paginiVentricular Septal DefectpepotchÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of LaminatedDocument31 paginiAnalysis of LaminatedKaustubh JadhavÎncă nu există evaluări

- In-Service Welding of Pipelines Industry Action PlanDocument13 paginiIn-Service Welding of Pipelines Industry Action Planعزت عبد المنعم100% (1)

- Government of West Bengal:: Tata Motors LTD: Abc 1 1 1 1 NA 0 NA 0Document1 paginăGovernment of West Bengal:: Tata Motors LTD: Abc 1 1 1 1 NA 0 NA 0md taj khanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Application of PCA-CNN (Principal Component Analysis - Convolutional Neural Networks) Method On Sentinel-2 Image Classification For Land Cover MappingDocument5 paginiApplication of PCA-CNN (Principal Component Analysis - Convolutional Neural Networks) Method On Sentinel-2 Image Classification For Land Cover MappingIJAERS JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- Serial Analysis of Gene Expression (SAGE)Document34 paginiSerial Analysis of Gene Expression (SAGE)Rohit PhalakÎncă nu există evaluări

- #Dr. Lora Ecg PDFDocument53 pagini#Dr. Lora Ecg PDFمحمد زينÎncă nu există evaluări

- Digital Signal Processing: B.E Ece (5Th Semester)Document17 paginiDigital Signal Processing: B.E Ece (5Th Semester)Saatwat CoolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Updating - MTO I - Unit 2 ProblemsDocument3 paginiUpdating - MTO I - Unit 2 ProblemsmaheshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maha Shivratri: (Shiv Avtaran, Incarnation of God)Document4 paginiMaha Shivratri: (Shiv Avtaran, Incarnation of God)Varsha RoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- UC Lennox Serie 13 Acx Merit R-410aDocument52 paginiUC Lennox Serie 13 Acx Merit R-410ajmurcia80Încă nu există evaluări

- DNA Mutation and Its Effect To An Individual (w5)Document6 paginiDNA Mutation and Its Effect To An Individual (w5)Cold CoockiesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Recycling Mind MapDocument2 paginiRecycling Mind Mapmsole124100% (1)

- Complete Processing Lines For Extruded Pet FoodDocument13 paginiComplete Processing Lines For Extruded Pet FoodденисÎncă nu există evaluări

- Army Aviation Digest - Nov 1978Document52 paginiArmy Aviation Digest - Nov 1978Aviation/Space History Library100% (1)

- St. John's Wort: Clinical OverviewDocument14 paginiSt. John's Wort: Clinical OverviewTrismegisteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shell Gadus: Designed To Do More. Just Like Our Greases - Shell GadusDocument2 paginiShell Gadus: Designed To Do More. Just Like Our Greases - Shell Gadusperi irawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maths All FormulasDocument5 paginiMaths All FormulasVishnuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fentanyl - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument13 paginiFentanyl - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaKeren SingamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quarter 4 English As Grade 4Document28 paginiQuarter 4 English As Grade 4rubyneil cabuangÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Tired BrainDocument3 paginiA Tired BrainSivasonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pre RmoDocument4 paginiPre RmoSangeeta Mishra100% (1)

- IPC's 2 Edition of Guidance Manual For Herbs and Herbal Products Monographs ReleasedDocument1 paginăIPC's 2 Edition of Guidance Manual For Herbs and Herbal Products Monographs ReleasedRakshaÎncă nu există evaluări