Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Vitiligo - Management and Prognosis - UpToDate

Încărcat de

BoneyJalgarTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Vitiligo - Management and Prognosis - UpToDate

Încărcat de

BoneyJalgarDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Author: Pearl E Grimes, MD

Section Editor: Hensin Tsao, MD, PhD

Deputy Editor: Rosamaria Corona, MD, DSc

Contributor Disclosures

All topics are updated as new evidence becomes available and our peer review process is complete.

Literature review current through: Jun 2019. | This topic last updated: May 05, 2017.

INTRODUCTION

Vitiligo is a relatively common acquired chronic disorder of pigmentation characterized

by the development of white macules on the skin due to loss of epidermal melanocytes

[1,2]. The depigmented areas are often symmetrical and usually increase in size with

time. Given the contrast between the white patches and areas of normal skin, the

disease is most disfiguring in darker skin types and has a profound impact on the

quality of life of children and adults [3,4]. Patients with vitiligo often experience

stigmatization, isolation, and low self-esteem [5-8].

Although there is no cure for the disease, the available treatments may halt the

progression of the disease and induce varying degrees of repigmentation with

acceptable cosmetic results in many cases. This topic review will discuss the

management of vitiligo. The pathogenesis, clinical features, and diagnosis of vitiligo are

discussed separately. Other pigmentation disorders are also discussed separately.

● (See "Vitiligo: Pathogenesis, clinical features, and diagnosis".)

● (See "Acquired hypopigmentation disorders other than vitiligo".)

● (See "Acquired hyperpigmentation disorders".)

● (See "Melasma".)

● (See "Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation".)

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 1 of 29

PATIENT EVALUATION

Assessment of severity — The evaluation of the patient with vitiligo involves a

detailed history and a complete skin examination to assess disease severity and

individual prognostic factors. Factors that may influence the approach to treatment

include:

● Age at onset of lesions

● Type of vitiligo (segmental, nonsegmental)

● Mucosal involvement, Koebner phenomenon

● Rate of progression or spread of lesions

● Previous episodes of repigmentation

● Type and response to previous treatments

● Family history of vitiligo and/or autoimmune diseases

● Presence of concomitant diseases

● Current medications and supplements

● Occupation, exposure to chemicals

● Effects of disease on the quality of life

A full-body skin examination should be performed to assess the extent of the disease,

with particular attention to sites of vitiligo predilection, such as the lips and perioral area,

periocular areas, dorsal surface of the hands, fingers, flexor surface of the wrists,

elbows, axillae, nipples, umbilicus, sacrum, groin, inguinal/anogenital regions, and

knees [9]. The percentage of the body area involved can be estimated by the so-called

1 percent rule or "palm method." In both children and adults, the palm of the hand,

including the fingers, is approximately 1 percent of the total body surface area (TBSA),

while the palm excluding the fingers is approximately 0.5 percent of the TBSA. An

alternative method is the "rule of nines":

● Each leg represents 18 percent of the TBSA.

● Each arm represents 9 percent of the TBSA.

● The anterior and posterior trunk each represent 18 percent of the TBSA.

● The head represents 9 percent of the TBSA.

Goals of treatment — The goals of treatment for vitiligo should be set with the

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 2 of 29

individual patient or parents in the case of children, based upon the patient's age and

skin type, the extent, location, and degree of disease activity, and the impact of the

disease on the patient's quality of life. An open discussion with the patient about the

limitations of treatment may be helpful to create realistic expectations.

Nonsegmental vitiligo has an unpredictable course, and treatment is often challenging.

However, multiple therapies, including topical agents, light therapies, and autologous

grafting procedures, have demonstrated efficacy for repigmentation of vitiligo [10]. The

response to treatments is generally slow and may be highly variable among patients

and among different body areas in the same patient. The best outcomes are often

achieved in darker skin types (Fitzpatrick IV to VI), although satisfactory results are

often seen also in lighter skin types (Fitzpatrick II, III). Facial and truncal lesions

respond well to treatment, while acral areas are extremely difficult to treat.

Psychosocial aspects — The patient's psychologic profile and ability to cope with a

lifelong disease should be carefully evaluated at the time of treatment planning.

Psychologic support should be offered to patients if needed. (See 'Psychologic

interventions' below.)

APPROACH

Our approach to the management of patients with vitiligo is generally consistent with

published guidelines [11,12]. Topical, systemic, and light-based therapies are available

for the stabilization and repigmentation of vitiligo (table 1) [13-17]. Treatment modalities

are chosen in the individual patient on the basis of the disease severity, patient

preference (including cost and accessibility), and response evaluation. Combination

therapies, such as phototherapy plus topical or oral corticosteroids, are usually more

effective than single therapies [18]. Despite treatment, however, vitiligo has a highly

unpredictable course, and the long-term persistence of repigmentation cannot be

predicted [18].

Stabilization of rapidly progressive disease — For patients who experience rapid

progression of vitiligo, with depigmented macules spreading over a few weeks or

months, we suggest low-dose oral corticosteroids as first-line therapy for the

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 3 of 29

stabilization (cessation of spread) of the disease (table 1). Oral prednisone is given at

the dose of 5 to 10 mg per day in children and 10 to 20 mg per day in adults for a

maximum of two weeks. If needed, treatment can be repeated in four to six weeks.

In adult patients, alternatives to oral prednisone include oral mini-pulse therapy with

dexamethasone 2.5 mg on two consecutive days weekly for an average of three

months or intramuscular triamcinolone 40 mg in a single administration. Treatment with

triamcinolone can be repeated in four to six weeks for a maximum of three injections.

(See 'Systemic corticosteroids' below.)

Stabilization therapy can be given with or without concomitant narrowband ultraviolet B

(NB-UVB) phototherapy. However, for patients with active disseminated disease

affecting multiple anatomic sites, we suggest that systemic corticosteroids and NB-UVB

phototherapy be initiated concomitantly. The disease is expected to stabilize in one to

three months.

In both adults and children in whom systemic corticosteroids are contraindicated, NB-

UVB phototherapy alone may be used to stabilize active vitiligo. NB-UVB is

administered two to three times weekly. (See 'Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy'

below.)

Vitiligo involving <10 percent of the TBSA

Localized disease — In patients with nonsegmental stable vitiligo (no increase in

size of existing lesions and absence of new lesions in the previous three to six months)

that involves <10 percent of the total body surface area (TBSA) and is limited to the

face, neck (picture 1), trunk, or extremities, mid- to high-potency topical corticosteroids

(groups two to four (table 2)) are the first-line therapy [12,19]. High-potency and mid-

potency topical corticosteroids are applied to the involved skin once and twice daily,

respectively. Agents with negligible systemic or local side effects, such as mometasone

furoate, are preferred [12]. (See 'Topical corticosteroids' below.)

There are no studies evaluating the optimal duration of treatment with topical

corticosteroids. In the author's experience, topical corticosteroids can be used safely for

two to three months, interrupted for one month, and then resumed for an additional two

or three months. Others suggest a discontinuous scheme (eg, once-daily application for

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 4 of 29

15 days per month for six months) [11,12,20].

Patients must be monitored closely for adverse effects of topical corticosteroids, which

include skin atrophy, telangiectasias, hypertrichosis, and acneiform eruptions. Limited

quantities should be prescribed.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus) are the preferred first-line

therapy in patients with limited disease involving the face or areas at high risk for skin

atrophy. Topical calcineurin inhibitors are generally applied twice daily. They can also be

used in combination with a topical corticosteroid for the first month or two, applying

each one once daily. (See 'Topical calcineurin inhibitors' below.)

For patients with limited disease who do not respond to topical corticosteroids or topical

calcineurin inhibitors, targeted phototherapy administered twice weekly is an option

(picture 2). (See 'Targeted phototherapy' below.)

Disseminated disease — For patients with disseminated areas of depigmentation

affecting multiple anatomic sites but overall involvement of less than 10 percent of the

TBSA, we suggest NB-UVB phototherapy as first-line therapy. NB-UVB phototherapy is

administered two to three times weekly. In the author's experience, less than 50

treatments are usually sufficient to achieve optimal outcomes. (See 'Narrowband

ultraviolet B phototherapy' below.)

Segmental vitiligo — Topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, or targeted

phototherapy are the first-line therapy for segmental vitiligo. (See 'Topical

corticosteroids' below and 'Topical calcineurin inhibitors' below and 'Targeted

phototherapy' below.)

NB-UVB phototherapy can be used for more extensive disease affecting multiple

dermatomes. For patients who do not respond to topical or light therapies, autologous

grafting is a second-line option [21]. Given the stable nature of segmental vitiligo, long-

term repigmentation can be achieved with autologous melanocyte transplantation [22].

(See 'Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy' below and 'Surgical therapies' below.)

Localized recalcitrant vitiligo — Surgical procedures are a therapeutic option for

patients with localized stable vitiligo that does not respond to topical agents or NB-UVB

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 5 of 29

phototherapy. Autologous grafting techniques include 1-mm punch grafts, suction blister

grafts, or cellular suspensions. While all these techniques have proven success, most

are technically challenging and expensive. One-millimeter punch grafts, however, can

be performed with ease and without the need of special devices or equipment. (See

'Surgical therapies' below.)

Vitiligo involving 10 to 40 percent of the TBSA — For adults and children with stable

nonsegmental vitiligo involving 10 to 40 percent of the TBSA, we suggest NB-UVB as

first-line therapy (picture 3). (See 'Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy' below.)

NB-UVB is administered two to three times per week for an average of 9 to 12 months.

Follicular areas of repigmentation usually begin to appear after 15 to 20 NB-UVB

treatments (picture 4). If patients are responding well with continued repigmentation,

treatment can be maintained beyond 9 to 12 months and up to 24 months or 200

sessions and then tapered off. Mid-potency topical corticosteroids or topical calcineurin

inhibitors are often intermittently used in combination with phototherapy.

Home NB-UVB phototherapy is an option for patients unable to travel to the clinician's

office for weekly treatments [23]. Whole-body or portable, handheld units are available

on the market (sample brand names include Daavlin, National Biological Solarc

Systems). Patients should be provided with detailed instructions on the use of the home

phototherapy units and return for in-office clinician follow-up on a regular basis.

Vitiligo involving >40 percent of the TBSA — NB-UVB is the first-line therapy for

patients with extensive vitiligo involving greater than 40 percent of the TBSA. The

suggested regimen and duration of treatment are similar to that discussed above for

patients with more limited disease. (See 'Vitiligo involving 10 to 40 percent of the TBSA'

above.)

However, for patients with extensive recalcitrant vitiligo that does not respond to

repigmentation regimens and for patients with extensive vitiligo who do not desire

undergoing repigmentation treatments, depigmentation of residual normally pigmented

areas utilizing topical monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone (monobenzone) may be an

option. Depigmentation therapy is usually initiated with monobenzone 10% cream for

one month and then continued with monobenzone 20% cream. Monobenzone is

applied on the areas of residual pigmentation once or twice daily; we typically treat

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 6 of 29

exposed areas first. These sites include the face, neck, upper extremities, chest, and

lower legs. Depigmentation usually begins at distant sites (where the drug has not been

applied) after three to six months of continued use. Depigmentation therapy may

require one to three years to achieve optimal outcomes. (See 'Depigmentation' below.)

Side effects of monobenzone are dose-dependent and include irritant contact dermatitis

and severe xerosis. Monobenzone should never be used as a lightening agent in cases

other than vitiligo. It will induce vitiligo in normal individuals.

Response assessment — Initial response to treatment is in most cases indicated by

the appearance of perifollicular areas of repigmentation in the vitiliginous patch, which

usually begins 8 to 12 weeks after the initiation of treatment or after 15 to 20 NB-UVB

sessions (picture 4). Some patients may show a diffuse repigmentation pattern or a

combination of diffuse and perifollicular [24,25]. Photographs should be taken before

starting treatment and at each follow-up visit to evaluate the degree of repigmentation.

In patients who respond well to treatment and achieve optimal repigmentation,

therapies can be gradually tapered and then discontinued. However, some patients may

require maintenance treatment. Intermittent use of topical corticosteroids or topical

calcineurin inhibitors (eg, twice weekly) and phototherapy every other week may be

used as long-term maintenance treatments. For patients who relapse after stopping

treatment or during the maintenance phase, another cycle of phototherapy can be

administered.

TREATMENT MODALITIES

Topical therapies

Topical corticosteroids — Mid- to super-high-potency topical corticosteroids are

commonly used as a first-line therapy for the treatment of limited vitiligo. Their efficacy

is attributed to modulation of the immune response.

The efficacy of topical corticosteroids as monotherapy for the treatment of vitiligo is

supported by a few small randomized trials [16]. A systematic review of 17 randomized

trials examined the effect of topical corticosteroids in combination with other therapies

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 7 of 29

(eg, narrowband ultraviolet B [NB-UVB], psoralen plus ultraviolet A with sunlight

[PUVAsol], excimer laser) [26]. The combination of potent or super-potent topical

corticosteroids (eg, betamethasone dipropionate, mometasone furoate, clobetasol

propionate) with light therapies is more effective than light therapies alone in inducing

repigmentation [27-29]. However, the quality of studies was generally poor, and the

study results could not be pooled because of considerable heterogeneity in study

design and outcome measure.

Adverse effects related to a prolonged use of topical corticosteroids, including folliculitis,

mild atrophy, telangiectasia, and hypertrichosis, have been reported, generally in a

small number of patients, in nearly all studies. Systemic absorption resulting in adrenal

suppression is a concern when large areas of skin and areas with thin skin are treated

for a prolonged time with potent steroids, especially in children [19].

Topical calcineurin inhibitors — Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are topical

immunomodulatory agents that affect the T-cell and mast-cell function and inhibit the

synthesis and release of multiple proinflammatory cytokines, including interferon-

gamma, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, and IL-10 [30-32]. In

contrast with topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors do not induce skin

atrophy, striae, or telangiectasias and are increasingly used for the treatment of facial

vitiligo.

The efficacy of tacrolimus and pimecrolimus alone or in combination with other

therapies for the treatment of nonsegmental vitiligo has been evaluated in several

randomized trials including either adults or children with vitiligo [26].

● In a randomized trial, 100 children (55 children with facial vitiligo; 45 with nonfacial

vitiligo) were treated with topical corticosteroid (clobetasol propionate 0.05%),

tacrolimus 0.1%, or placebo for six months [33]. Among children with facial vitiligo,

the success rate (defined as repigmentation >50 percent) was the same in the

topical corticosteroid and tacrolimus groups (58 percent); however, among children

with nonfacial vitiligo, the success rate was higher in the topical corticosteroid

group compared with the tacrolimus groups (39 versus 23 percent). The success

rate in the placebo group was 7 percent.

● Another randomized trial including 44 adult patients with stable vitiligo compared

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 8 of 29

0.1% tacrolimus ointment twice daily, 1% pimecrolimus cream twice daily, and NB-

UVB phototherapy three times a week for 24 weeks [34]. At the end of the study,

there was no significant difference among treatments in the repigmentation for any

anatomical site.

● In a 12-week open, randomized study, 53 patients with vitiligo were treated with

308 nm monochromatic excimer light (MEL) twice weekly plus 0.1% tacrolimus and

oral vitamin E daily, 308 nm MEL twice weekly plus daily oral vitamin E, or daily

oral vitamin E alone [35]. At the end of the study, good to excellent repigmentation

was achieved in 70 percent of patients in the MEL plus tacrolimus and vitamin E

group, 55 percent of those in the MEL plus vitamin E group, and in none of the

patients in the vitamin E group.

● In an open trial, 40 children with nonsegmental, focal, or segmental vitiligo were

treated with 0.1% mometasone furoate cream once daily or 1% pimecrolimus

cream twice daily for three months [36]. Moderate or marked responses were seen

in 11 patients (55 percent) in the mometasone furoate group and in 7 (35 percent)

in the pimecrolimus group, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Although the increased risk of skin cancer among transplant patients treated with

systemic calcineurin inhibitors is well recognized, the use of topical calcineurin inhibitors

does not seem to be associated with an increased risk for skin or systemic

malignancies [37-39]. However, based upon animal studies documenting an increased

risk of lymphoma and skin cancers associated with topical or systemic exposure to

calcineurin inhibitors and to reports of cancer cases in children who used topical

pimecrolimus or tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis, in 2006 the US Food and Drug

Administration placed a boxed warning on the prescribing information for these

medications. Labeling also recommends that these agents should not be used in

combination with ultraviolet (UV) light therapy.

Unproven topical therapies — The benefit of topical vitamin D3 analogues in the

treatment of vitiligo is controversial. A few small randomized trials evaluated the role of

calcipotriol and tacalcitol in combination with psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA),

narrowband ultraviolet (NB-UV), or natural sunlight for the treatment of nonsegmental

vitiligo with conflicting results [40-42].

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 9 of 29

● In a prospective right-left 24-week comparative study including 24 patients with

vitiligo, there were no statistically significant differences between the sides treated

with NB-UVB monotherapy and the sides treated with NB-UVB plus calcipotriol

[41].

● In another right-left comparative study, 35 patients with generalized vitiligo applied

calcipotriol 0.05 mg/g cream or placebo to the reference lesions one hour before

PUVA treatment twice weekly [40]. Lesions on the side treated with calcipotriol plus

PUVA had a fourfold increase in the likelihood of achieving greater than 75 percent

repigmentation sooner than the side treated with placebo plus PUVA (mean

number of PUVA sessions 9 and 12, respectively).

Phototherapy

Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy — NB-UVB involves the use of UV lamps

with a peak emission of approximately 311 nm [43]. These shorter wavelengths provide

higher-energy fluences and induce less cutaneous erythema. NB-UVB induces local

immunosuppression and apoptosis; stimulates the production of melanocyte-stimulating

hormones, basic fibroblasts, growth factor, and endothelin I; and increases melanocyte

proliferation and melanogenesis [43-45]. (See "UVB therapy (broadband and

narrowband)".)

Due to its lack of systemic toxicity and its good safety profile in both children and adults,

NB-UVB phototherapy has emerged as the initial treatment of choice for patients with

vitiligo involving >10 percent of the body surface area (BSA). NB-UVB can be used for

both stabilization and repigmentation of vitiligo (picture 3).

A meta-analysis of three randomized trials comparing oral PUVA with NB-UVB found a

60 percent higher proportion of participants achieving >75 percent repigmentation in the

NB-UVB group compared with the oral PUVA group [26]. The additive effect of

tacrolimus ointment (0.1%) applied once daily combined with NB-UVB in the treatment

of vitiligo has been evaluated in one randomized trial [46]. In this study, 40 patients with

stable, symmetrical vitiligo were treated with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% on one side of

their body and a placebo ointment on the other side plus whole-body NB-UVB two or

three times weekly for at least three months. In 27 of 40 patients, a greater reduction in

the target lesion area was seen in the side treated with tacrolimus compared with the

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 10 of 29

side treated with NB-UVB alone (42 versus 29 percent). However, a possible increase

in the risk of skin cancer with this combination therapy cannot be excluded.

A 2017 meta-analysis of 35 randomized and nonrandomized studies including 1428

patients compared the repigmentation rates of NB-UVB and PUVA by treatment

duration [47]. For NB-UVB, a ≥75 percent repigmentation was achieved by 13, 19, and

36 percent of patients at 3, 6, and 12 months of treatment, respectively. For PUVA, ≥75

percent repigmentation was achieved by 9 percent of patients at 6 months and 14

percent at 12 months. The results of this meta-analysis confirm the superiority of NB-

UVB over PUVA and suggest that phototherapy should be continued for at least 12

months to achieve a maximal response.

Only a few small observational studies have evaluated the duration of repigmentation in

patients with vitiligo treated with phototherapy. In a small observational study of 11

patients followed up for two years after treatment with NB-UVB phototherapy, five

maintained areas of repigmentation and six experienced complete or partial relapse of

vitiligo at previously repigmented sites [48]. In another study including 15 children

treated with NB-UVB phototherapy and followed up for a mean of 12 months after

completing treatment, six showed stable repigmentation, four further improvement, and

three complete or partial regression of the pigmentation achieved with treatment [49].

PUVA photochemotherapy — Historically, photochemotherapy with topical or

systemic PUVA radiation was the "gold standard" treatment for the repigmentation of

vitiligo but has been largely replaced by NB-UVB phototherapy. PUVA is associated with

substantial adverse effects, including phototoxicity and gastrointestinal discomfort, and

requires patients to use ocular protection for 12 to 24 hours following treatment. In

addition, the long-term risk of skin cancer is well established for PUVA [50]. (See

"Psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) photochemotherapy".)

Targeted phototherapy — Targeted phototherapy using 308 nm monochromatic

excimer lamps or lasers has demonstrated efficacy for the treatment of localized vitiligo

(picture 2) [51]. These devices deliver high-intensity light only to the affected areas

while avoiding exposure of the healthy skin and lowering the cumulative ultraviolet B

(UVB) dose. (See "Targeted phototherapy".)

A systematic review of six randomized trials (411 patients with 764 lesions) found that

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 11 of 29

excimer lamps and excimer lasers were equally effective in inducing ≥50 percent and

≥75 percent repigmentation [52]. Although the repigmentation may occur more rapidly

with more frequent weekly treatments, the final result appears to be related to the

overall number of treatment sessions rather than their frequency [53].

As with NB-UVB, targeted phototherapy can work synergistically with topical therapies,

including tacrolimus ointment and topical corticosteroids [12,54].

● In a study of eight patients with vitiligo, 24 symmetric vitiliginous areas were treated

with the excimer laser three times per week for a total of 24 treatments [55]. Topical

tacrolimus ointment or placebo was applied to randomized affected areas twice

daily throughout the length of the trial. Fifty percent of the areas treated with the

combination excimer laser and topical tacrolimus achieved ≥75 percent

repigmentation compared with 20 percent of the areas treated with placebo.

● In a 12-week open randomized study, 53 patients with vitiligo were treated with 308

nm MEL twice weekly plus 0.1% tacrolimus and oral vitamin E daily, 308 nm MEL

twice weekly plus daily oral vitamin E, or daily oral vitamin E alone [35]. At the end

of the study, good to excellent repigmentation was achieved in 70 percent of

patients in the MEL plus tacrolimus and vitamin E group, 55 percent of those in the

MEL plus vitamin E group, and in none of the patients in the vitamin E group.

Systemic therapies

Systemic corticosteroids — Low-dose oral corticosteroids are generally utilized for

the stabilization of rapidly progressive vitiligo, often in combination with NB-UVB

phototherapy. Evidence for their efficacy in halting the spread of vitiligo is limited to a

few uncontrolled studies [56-58].

● In one study, 81 patients were treated with prednisolone 0.3 mg/kg per day for two

months, and then the dose was progressively reduced in the subsequent three

months [56]. Control of disease progression was achieved in approximately 90

percent of patients and repigmentation in 74 percent.

● In another study, 40 patients with extensive or rapidly spreading vitiligo were

treated with oral mini-pulses of betamethasone or dexamethasone (5 mg in single

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 12 of 29

dose) on two consecutive days per week for several months. After one to three

months, vitiligo progression was arrested in 32 of 36 patients with active disease

[57].

Oral corticosteroids are not effective as a repigmenting therapy for stable vitiligo. In a

small open-label trial, 86 patients with progressive nonsegmental vitiligo were treated

with oral mini-pulses of betamethasone (0.1 mg/kg twice weekly on two consecutive

days for three months followed by 1 mg every month for the following three months)

alone or in combination with PUVA, NB-UVB, or broadband UVB [59]. At six months,

marked or moderate improvement was achieved in 15 percent of patients treated with

corticosteroids alone versus 85 percent of patients treated with corticosteroids plus

PUVA, 81 percent of those treated with corticosteroids plus NB-UVB, and 33 percent of

those treated with corticosteroids plus broadband-UVB.

Complementary and alternative therapies — Oral supplementation with

antioxidants and vitamins is often used as an adjunctive treatment for vitiligo, usually in

combination with phototherapy. However, there is limited evidence from high-quality

studies to support their use.

● Vitamins – A few small uncontrolled studies have reported stabilization and

repigmentation in vitiligo patients treated with UVB phototherapy and high-dose

vitamin supplementation, vitamin C, vitamin B12, and folic acid [60,61].

● Alpha-lipoic acid – Alpha-lipoic acid is an organosulfur compound derived from

octanoic acid. It is widely available as an over-the-counter nutritional supplement

and has been marketed as an antioxidant. The efficacy of alpha-lipoic acid in

vitiligo was demonstrated in one randomized trial including 35 patients with

nonsegmental vitiligo [62]. In this study, twice-daily oral supplementation with

alpha-lipoic acid, vitamin E, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and cysteine monohydrate

combined with NB-UVB twice weekly for six months resulted in significantly more

patients (47 versus 18 percent) achieving >75 percent repigmentation compared

with phototherapy alone. In addition, repigmentation occurred earlier with lower

cumulative UVB dose. Biochemical evaluations at two and six months showed

increased catalase activity, decreased intracellular reactive oxygen species

production, and reduced membrane peroxidation in the combination-treatment

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 13 of 29

group. Despite these promising results, further studies are needed to confirm the

benefit of alpha-lipoic acid supplementation in the management of vitiligo.

● Ginkgo biloba – Extracts from the Ginkgo biloba leaf have long been used in

traditional Chinese medicine to treat various conditions, including cutaneous,

neurologic, and vascular disorders. The two main groups of active constituents

responsible for G. biloba's medicinal effects are terpene lactones (ginkgolides and

bilobalides) and ginkgo flavone glycosides, which are present in varying

concentrations in the leaf of the ginkgo tree. (See "Clinical use of ginkgo biloba".)

Only a few investigations have evaluated ginkgo's use in the management of

vitiligo.

• A small randomized trial reported that the spread of vitiligo was arrested in 20

of 25 subjects receiving 40 mg of G. biloba extract three times daily for six

months but in none of 22 subjects in the placebo group [63]. In addition, 10

patients in the active treatment group but only two in the placebo group

showed >75 percent repigmentation.

• Another pilot study found significant improvements in total Vitiligo Area Scoring

Index and Vitiligo European Task Force assessment in 12 participants

following 12 weeks of supplementation with twice-daily G. biloba extract [64].

In addition to repigmentation, active depigmentation ceased in all patients with

acrofacial vitiligo.

● Polypodium leucotomos – In one randomized trial, NB-UVB in combination with

oral extracts of Polypodium leucotomos, a tropical fern with antioxidant and

immunomodulator properties, was more effective than NB-UVB alone in inducing

repigmentation of vitiligo in the head and neck area (50 versus 19 percent) after 25

weeks [65]. No difference was noted in other body areas.

Surgical therapies — Surgical therapies have been used for vitiligo for the past 25

years and remain viable options for patients with localized depigmented areas that have

been unresponsive to medical intervention [66-69]. They include:

● Autologous suction blister grafts [70,71]

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 14 of 29

● Minigrafts or punch grafts [72-74]

● Split-thickness grafts [75,76]

● Autologous melanocyte cultures

● Cultured epidermal suspensions [77,78]

● Autologous noncultured epidermal cell suspension [79]

● Hair follicle transplantation [80-82]

The scope of transplantation procedures is the transfer of a reservoir of healthy

melanocytes to vitiliginous skin for proliferation and migration into areas of

depigmentation. Transplantation procedures are contraindicated for patients with a

history of hypertrophic scars or keloids.

A systematic review of randomized trials and observational studies of autologous

transplantation methods for vitiligo concluded that maximal repigmentation occurred in

patients treated with split-thickness grafting and epidermal blister grafting [66]. Both

treatment groups achieved success rates of 90 percent repigmentation.

Other studies have reported the benefits of transplantation of autologous melanocyte

cultures and epidermal suspensions containing both melanocytes and keratinocytes

[67,77,79]. In one randomized trial comparing autologous noncultured epidermal cell

suspension with suction blister grafts in 41 patients, a repigmentation ≥75 percent was

achieved in over 85 percent of lesions in both treatment groups [79]. However, more

lesions in the noncultured epidermal cell suspension group achieved a 90 to 100

percent repigmentation compared with those in the suction blister group (70 versus 27

percent).

Adverse effects of surgical therapies include cobblestoning, scarring, graft

depigmentation, and graft displacement. Suction blister grafts and split skin grafts may

be associated with the Koebner phenomenon at the donor site, a complication of major

clinical importance since it results in the development of new vitiligo lesions [26]. Other

adverse effects include hypopigmentation, hyperpigmentation, scarring, and infection at

both donor and recipient sites. Punch grafting or minigrafting adverse effects include

lack of color blending and matching with the surrounding normal skin, cobblestoning,

and "polka dot" appearance [83].

Factors influencing the outcome of transplantation techniques include age, site of

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 15 of 29

lesion, and type of vitiligo. In a series of 117 patients, the best results were achieved for

patients younger than age 20 and patients with segmental vitiligo, whereas the grafting

site did not significantly affect the outcome [68].

Depigmentation — Since the 1950s, monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone

(monobenzone) has been used as a depigmenting agent for patients with extensive

vitiligo [84,85]. Monobenzone causes permanent destruction of melanocytes and

induces depigmentation locally and remotely from the sites of application. Thus, the use

of monobenzone for other disorders of pigmentation is contraindicated. The major side

effects of monobenzone therapy are irritant contact dermatitis and pruritus, which

usually respond to topical and systemic steroids. Other side effects include severe

xerosis, alopecia, and premature graying.

Experimental therapies

● Afamelanotide – Afamelanotide, a potent and longer-lasting synthetic analog of

naturally occurring alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH), is a novel

intervention for vitiligo [86,87]. Its use is based upon the demonstration of defects

in the melanocortin system in patients with vitiligo, including decreased circulating

and lesional skin levels of alpha-MSH [88]. Afamelanotide is delivered as a

subcutaneous, bioresorbable implant that promotes melanocyte proliferation and

melanogenesis.

The safety and efficacy of afamelanotide implants combined with NB-UVB were

assessed in an observational study of four patients with generalized vitiligo [86].

Patients were treated three times weekly with NB-UVB for one month and then

administered a series of four monthly implants containing 16 mg of afamelanotide.

Follicular and confluent areas of repigmentation were evident within two days to

four weeks after the initial implant. Afamelanotide induced fast and deep

repigmentation as well as diffuse hyperpigmentation in all cases. In a subsequent

randomized trial including 55 patients with skin type III to VI and vitiligo involving 15

to 50 percent of the BSA, patients in the NB-UVB plus afamelanotide group

achieved a greater repigmentation than patients in the NB-UVB monotherapy

group at five months (49 versus 33 percent) [87].

● Prostaglandin E2 – Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is a potentially beneficial treatment

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 16 of 29

for localized stable vitiligo. PGE2 controls the proliferation of melanocytes by

means of stimulant and immunomodulatory effects. In a consecutive series of

patients with stable vitiligo, repigmentation occurred in 40 of 56 patients treated

with PGE2 0.25 mg/g gel twice daily for six months [89]. The response was

excellent in 22 of 40 patients, with complete repigmentation observed in eight

patients.

● Bimatoprost – Bimatoprost, a synthetic analog of prostaglandin F2-alpha approved

for the topical treatment of glaucoma and hypotrichosis of the eyelashes, is

associated with hyperpigmentation of periocular skin caused by increased

melanogenesis [90]. The efficacy of bimatoprost in the treatment of vitiligo was

initially evaluated in a preliminary study of 10 patients with localized vitiligo treated

with bimatoprost 0.03% ophthalmic solution twice daily for four months [91]. Of the

10 patients, three had 100 percent repigmentation, three had 75 to 99 percent

repigmentation, and one patient had 50 to 75 percent repigmentation. The best

responses were observed on the face.

A subsequent proof-of-concept randomized trial compared the efficacy of

bimatoprost 0.03% ophthalmic solution alone and in combination with a topical

steroid (mometasone) with mometasone alone in 32 patients with nonsegmental,

nonfacial stable vitiligo involving <5 percent of the body surface area [92]. At 20

weeks, none of the patients achieved the prespecified end point of 50 to 75 percent

repigmentation. However, in a post-hoc analysis using a less stringent definition of

response (25 to 50 percent repigmentation), patients treated with bimatoprost,

either alone or with mometasone, achieved a greater repigmentation in the neck

and trunk than patients treated with mometasone alone.

● Topical ruxolitinib – Ruxolitinib is a Janus kinase 1 and 2 inhibitor approved for the

treatment of intermediate- or high-risk myelofibrosis and polycythemia vera. In a

phase 2, proof-of-concept trial, topical ruxolitinib 1.5% cream was administered

twice daily to 11 adult patients with vitiligo involving at least 1 percent of the body

surface area for 20 weeks [93]. Eight of 11 patients had some response to

treatment, with a mean improvement of the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index of 23

percent. The best response was observed in patients with facial vitiligo. The main

adverse effect was erythema over the treated lesion.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 17 of 29

PSYCHOLOGIC INTERVENTIONS

There is a scarcity of high-quality studies evaluating the efficacy of psychologic

interventions in the management of patients with vitiligo. One small randomized trial

found that cognitive-behavioral therapy in addition to conventional therapies was

effective in improving the quality of life, self-esteem, and perceived body image in adult

patients with vitiligo and even influenced the course of the disease itself [94].

CAMOUFLAGE

Cosmetic camouflage can be beneficial for patients with vitiligo affecting exposed areas

such as the face, neck, and hands. Camouflage products include foundation-based

cosmetics and self-tanning products containing dihydroxyacetone (DHA). DHA-based

products are most popular because they provide lasting color for up to several days and

are not immediately rubbed off onto clothing. Tattooing or micropigmentation should be

avoided, given the risk of koebnerization and oxidation of tattoo pigment causing further

dyschromia. (See "Vitiligo: Pathogenesis, clinical features, and diagnosis", section on

'Koebner phenomenon'.)

PROGNOSIS

Vitiligo is a chronic disease with a highly unpredictable course. Early-onset vitiligo

appears to be associated with involvement of a greater body surface area involvement

and increased rate of disease progression [95]. Despite treatment, most patients

experience alternating periods of pigment loss and disease stability for their entire life.

Occasionally, patients may experience spontaneous repigmentation.

Patients who have organ-specific autoantibodies have an increased risk of developing

subclinical or overt autoimmune disease [96]. (See "Vitiligo: Pathogenesis, clinical

features, and diagnosis", section on 'Associated disorders'.)

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 18 of 29

● Vitiligo is a chronic, relapsing disease. The goals of treatment include the

stabilization of active disease and the repigmentation of depigmented patches.

However, the response to treatments is slow and may be highly variable among

patients and among different body areas in the same patient. (See 'Patient

evaluation' above and 'Assessment of severity' above and 'Goals of treatment'

above.)

● In patients with rapidly progressive vitiligo (ie, depigmented macules spreading

over a few weeks or months), we suggest systemic corticosteroids as adjunct

therapy to narrowband ultraviolet B (NB-UVB) phototherapy for stabilization (Grade

2C). (See 'Stabilization of rapidly progressive disease' above.)

● For patients with vitiligo involving <10 percent of the total body surface area

(TBSA), we suggest topical corticosteroids as initial therapy (Grade 2C). Topical

corticosteroids are applied once daily for two to three months and then interrupted

for one month. Topical calcineurin inhibitors are preferred to topical corticosteroids

for body areas at increased risk of atrophy. Targeted phototherapy is an option for

patients with limited vitiligo who do not respond to topical therapies. (See 'Vitiligo

involving <10 percent of the TBSA' above.)

● For patients with vitiligo involving 10 to 40 percent of the TBSA, we suggest

phototherapy with NB-UVB (Grade 2B). Phototherapy is administered two to three

times per week for 9 to 12 months or up to 200 treatments. Topical corticosteroids

or topical calcineurin inhibitors may be intermittently used in combination with NB-

UVB phototherapy. (See 'Vitiligo involving 10 to 40 percent of the TBSA' above.)

● Surgical therapies involving the autologous transplantation of healthy melanocytes

in depigmented areas are an option for patients with localized, recalcitrant vitiligo

and for patients with segmental vitiligo. (See 'Localized recalcitrant vitiligo' above

and 'Segmental vitiligo' above.)

● Depigmentation of residual pigmented areas with monobenzyl ether of

hydroquinone (monobenzone) can be considered for patients with extensive

recalcitrant vitiligo that does not respond to repigmentation regimens and for those

with extensive vitiligo who do not desire undergoing repigmentation treatments.

(See 'Vitiligo involving >40 percent of the TBSA' above.)

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 19 of 29

Use of UpToDate is subject to the Subscription and License Agreement.

REFERENCES

1. Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, van Geel N. Vitiligo. Lancet 2015;

386:74.

2. Mohammed GF, Gomaa AH, Al-Dhubaibi MS. Highlights in pathogenesis of

vitiligo. World J Clin Cases 2015; 3:221.

3. Krüger C, Schallreuter KU. Stigmatisation, Avoidance Behaviour and Difficulties in

Coping are Common Among Adult Patients with Vitiligo. Acta Derm Venereol

2015; 95:553.

4. Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Quality of life impairment in children and adolescents

with vitiligo. Pediatr Dermatol 2014; 31:309.

5. Robins A. Biological Perspectives on Human Pigmentation, Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge, UK 2005. Vol 7.

6. Grimes PE. Disorders of pigmentation. In: ACP Medicine, Dale DC, Federman DD

(Eds), WebMD Scientific American Medicine, New York 2012. p.526.

7. Porter J. The psychological effects of vitiligo: Response to impaired appearance. I

n: Vitiligo, Hann SK, Nordlund JJ (Eds), Blackwell Science, Oxford, UK 2000. p.97

.

8. Daniel BS, Wittal R. Vitiligo treatment update. Australas J Dermatol 2015; 56:85.

9. Alikhan A, Felsten LM, Daly M, Petronic-Rosic V. Vitiligo: a comprehensive

overview Part I. Introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential

diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad

Dermatol 2011; 65:473.

10. Whitton M, Pinart M, Batchelor JM, et al. Evidence-based management of vitiligo:

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 20 of 29

summary of a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Dermatol 2016; 174:962.

11. Oiso N, Suzuki T, Wataya-Kaneda M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and

treatment of vitiligo in Japan. J Dermatol 2013; 40:344.

12. Taieb A, Alomar A, Böhm M, et al. Guidelines for the management of vitiligo: the

European Dermatology Forum consensus. Br J Dermatol 2013; 168:5.

13. Yaghoobi R, Omidian M, Bagherani N. Vitiligo: a review of the published work. J

Dermatol 2011; 38:419.

14. Faria AR, Tarlé RG, Dellatorre G, et al. Vitiligo--Part 2--classification,

histopathology and treatment. An Bras Dermatol 2014; 89:784.

15. Falabella R, Barona MI. Update on skin repigmentation therapies in vitiligo.

Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2009; 22:42.

16. Njoo MD, Spuls PI, Bos JD, et al. Nonsurgical repigmentation therapies in vitiligo.

Meta-analysis of the literature. Arch Dermatol 1998; 134:1532.

17. Grimes PE. Vitiligo. An overview of therapeutic approaches. Dermatol Clin 1993;

11:325.

18. Ezzedine K, Whitton M, Pinart M. Interventions for Vitiligo. JAMA 2016; 316:1708.

19. Kwinter J, Pelletier J, Khambalia A, Pope E. High-potency steroid use in children

with vitiligo: a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 56:236.

20. Meredith F, Abbott R. Vitiligo: an evidence-based update. Report of the 13th

Evidence Based Update Meeting, 23 May 2013, Loughborough, U.K. Br J

Dermatol 2014; 170:565.

21. Mulekar SV, Al Eisa A, Delvi MB, et al. Childhood vitiligo: a long-term study of

localized vitiligo treated by noncultured cellular grafting. Pediatr Dermatol 2010;

27:132.

22. Mulekar SV. Long-term follow-up study of segmental and focal vitiligo treated by

autologous, noncultured melanocyte-keratinocyte cell transplantation. Arch

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 21 of 29

Dermatol 2004; 140:1211.

23. Eleftheriadou V, Thomas K, Ravenscroft J, et al. Feasibility, double-blind,

randomised, placebo-controlled, multi-centre trial of hand-held NB-UVB

phototherapy for the treatment of vitiligo at home (HI-Light trial: Home Intervention

of Light therapy). Trials 2014; 15:51.

24. Parsad D, Pandhi R, Dogra S, Kumar B. Clinical study of repigmentation patterns

with different treatment modalities and their correlation with speed and stability of

repigmentation in 352 vitiliginous patches. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004; 50:63.

25. Gan EY, Gahat T, Cario-André M, et al. Clinical repigmentation patterns in

paediatric vitiligo. Br J Dermatol 2016; 175:555.

26. Whitton ME, Pinart M, Batchelor J, et al. Interventions for vitiligo. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2015; :CD003263.

27. Sassi F, Cazzaniga S, Tessari G, et al. Randomized controlled trial comparing the

effectiveness of 308-nm excimer laser alone or in combination with topical

hydrocortisone 17-butyrate cream in the treatment of vitiligo of the face and neck.

Br J Dermatol 2008; 159:1186.

28. Akdeniz N, Yavuz IH, Gunes Bilgili S, et al. Comparison of efficacy of narrow band

UVB therapies with UVB alone, in combination with calcipotriol, and with

betamethasone and calcipotriol in vitiligo. J Dermatolog Treat 2014; 25:196.

29. Khalid M, Mujtaba G, Haroon TS. Comparison of 0.05% clobetasol propionate

cream and topical Puvasol in childhood vitiligo. Int J Dermatol 1995; 34:203.

30. Tharp MD. Calcineurin inhibitors. Dermatol Ther 2002; 15:325.

31. Kang S, Lucky AW, Pariser D, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of tacrolimus

ointment for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in children. J Am Acad Dermatol

2001; 44:S58.

32. Grimes PE, Soriano T, Dytoc MT. Topical tacrolimus for repigmentation of vitiligo.

J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 47:789.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 22 of 29

33. Ho N, Pope E, Weinstein M, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled

trial of topical tacrolimus 0·1% vs. clobetasol propionate 0·05% in childhood

vitiligo. Br J Dermatol 2011; 165:626.

34. Stinco G, Piccirillo F, Forcione M, et al. An open randomized study to compare

narrow band UVB, topical pimecrolimus and topical tacrolimus in the treatment of

vitiligo. Eur J Dermatol 2009; 19:588.

35. Nisticò S, Chiricozzi A, Saraceno R, et al. Vitiligo treatment with monochromatic

excimer light and tacrolimus: results of an open randomized controlled study.

Photomed Laser Surg 2012; 30:26.

36. Köse O, Arca E, Kurumlu Z. Mometasone cream versus pimecrolimus cream for

the treatment of childhood localized vitiligo. J Dermatolog Treat 2010; 21:133.

37. Margolis DJ, Abuabara K, Hoffstad OJ, et al. Association Between Malignancy

and Topical Use of Pimecrolimus. JAMA Dermatol 2015; 151:594.

38. Thaçi D, Salgo R. The topical calcineurin inhibitor pimecrolimus in atopic

dermatitis: a safety update. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat 2007;

16:58, 60.

39. Ormerod AD. Topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus and the risk of cancer: how

much cause for concern? Br J Dermatol 2005; 153:701.

40. Ermis O, Alpsoy E, Cetin L, Yilmaz E. Is the efficacy of psoralen plus ultraviolet A

therapy for vitiligo enhanced by concurrent topical calcipotriol? A placebo-

controlled double-blind study. Br J Dermatol 2001; 145:472.

41. Khullar G, Kanwar AJ, Singh S, Parsad D. Comparison of efficacy and safety

profile of topical calcipotriol ointment in combination with NB-UVB vs. NB-UVB

alone in the treatment of vitiligo: a 24-week prospective right-left comparative

clinical trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015; 29:925.

42. Rodríguez-Martín M, García Bustínduy M, Sáez Rodríguez M, Noda Cabrera A.

Randomized, double-blind clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of topical tacalcitol

and sunlight exposure in the treatment of adult nonsegmental vitiligo. Br J

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 23 of 29

Dermatol 2009; 160:409.

43. Njoo MD, Bos JD, Westerhof W. Treatment of generalized vitiligo in children with

narrow-band (TL-01) UVB radiation therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 42:245.

44. Yones SS, Palmer RA, Garibaldinos TM, Hawk JL. Randomized double-blind trial

of treatment of vitiligo: efficacy of psoralen-UV-A therapy vs Narrowband-UV-B

therapy. Arch Dermatol 2007; 143:578.

45. Natta R, Somsak T, Wisuttida T, Laor L. Narrowband ultraviolet B radiation

therapy for recalcitrant vitiligo in Asians. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003; 49:473.

46. Nordal EJ, Guleng GE, Rönnevig JR. Treatment of vitiligo with narrowband-UVB

(TL01) combined with tacrolimus ointment (0.1%) vs. placebo ointment, a

randomized right/left double-blind comparative study. J Eur Acad Dermatol

Venereol 2011; 25:1440.

47. Bae JM, Jung HM, Hong BY, et al. Phototherapy for Vitiligo: A Systematic Review

and Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol 2017.

48. Sitek JC, Loeb M, Ronnevig JR. Narrowband UVB therapy for vitiligo: does the

repigmentation last? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007; 21:891.

49. Percivalle S, Piccinno R, Caccialanza M, Forti S. Narrowband ultraviolet B

phototherapy in childhood vitiligo: evaluation of results in 28 patients. Pediatr

Dermatol 2012; 29:160.

50. Stern RS, PUVA Follow-Up Study. The risk of squamous cell and basal cell cancer

associated with psoralen and ultraviolet A therapy: a 30-year prospective study. J

Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 66:553.

51. Grimes PE. Advances in the treatment of vitiligo: targeted phototherapy. Cosmet

Dermatol 2003; 16:18.

52. Lopes C, Trevisani VF, Melnik T. Efficacy and Safety of 308-nm Monochromatic

Excimer Lamp Versus Other Phototherapy Devices for Vitiligo: A Systematic

Review with Meta-Analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2016; 17:23.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 24 of 29

53. Hofer A, Hassan AS, Legat FJ, et al. Optimal weekly frequency of 308-nm

excimer laser treatment in vitiligo patients. Br J Dermatol 2005; 152:981.

54. Asawanonda P, Amornpinyokeit N, Nimnuan C. Topical 8-methoxypsoralen

enhances the therapeutic results of targeted narrowband ultraviolet B

phototherapy for plaque-type psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008;

22:50.

55. Kawalek AZ, Spencer JM, Phelps RG. Combined excimer laser and topical

tacrolimus for the treatment of vitiligo: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg 2004; 30:130.

56. Kim SM, Lee HS, Hann SK. The efficacy of low-dose oral corticosteroids in the

treatment of vitiligo patients. Int J Dermatol 1999; 38:546.

57. Pasricha JS, Khaitan BK. Oral mini-pulse therapy with betamethasone in vitiligo

patients having extensive or fast-spreading disease. Int J Dermatol 1993; 32:753.

58. Radakovic-Fijan S, Fürnsinn-Friedl AM, Hönigsmann H, Tanew A. Oral

dexamethasone pulse treatment for vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001; 44:814.

59. Rath N, Kar HK, Sabhnani S. An open labeled, comparative clinical study on

efficacy and tolerability of oral minipulse of steroid (OMP) alone, OMP with PUVA

and broad / narrow band UVB phototherapy in progressive vitiligo. Indian J

Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008; 74:357.

60. Don P, Iuga A, Dacko A, Hardick K. Treatment of vitiligo with broadband ultraviolet

B and vitamins. Int J Dermatol 2006; 45:63.

61. Elgoweini M, Nour El Din N. Response of vitiligo to narrowband ultraviolet B and

oral antioxidants. J Clin Pharmacol 2009; 49:852.

62. Dell'Anna ML, Mastrofrancesco A, Sala R, et al. Antioxidants and narrow band-

UVB in the treatment of vitiligo: a double-blind placebo controlled trial. Clin Exp

Dermatol 2007; 32:631.

63. Parsad D, Pandhi R, Juneja A. Effectiveness of oral Ginkgo biloba in treating

limited, slowly spreading vitiligo. Clin Exp Dermatol 2003; 28:285.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 25 of 29

64. Szczurko O, Shear N, Taddio A, Boon H. Ginkgo biloba for the treatment of vitilgo

vulgaris: an open label pilot clinical trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 2011;

11:21.

65. Middelkamp-Hup MA, Bos JD, Rius-Diaz F, et al. Treatment of vitiligo vulgaris with

narrow-band UVB and oral Polypodium leucotomos extract: a randomized double-

blind placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007; 21:942.

66. Njoo MD, Westerhof W, Bos JD, Bossuyt PM. A systematic review of autologous

transplantation methods in vitiligo. Arch Dermatol 1998; 134:1543.

67. van Geel N, Ongenae K, De Mil M, et al. Double-blind placebo-controlled study of

autologous transplanted epidermal cell suspensions for repigmenting vitiligo. Arch

Dermatol 2004; 140:1203.

68. Gupta S, Kumar B. Epidermal grafting in vitiligo: influence of age, site of lesion,

and type of disease on outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003; 49:99.

69. Falabella R. Surgical approaches for stable vitiligo. Dermatol Surg 2005; 31:1277.

70. Ashique KT, Kaliyadan F. Long-Term Follow-up and Donor Site Changes

Evaluation in Suction Blister Epidermal Grafting Done for Stable Vitiligo: A

Retrospective Study. Indian J Dermatol 2015; 60:369.

71. Gou D, Currimbhoy S, Pandya AG. Suction blister grafting for vitiligo: efficacy and

clinical predictive factors. Dermatol Surg 2015; 41:633.

72. Malakar S, Dhar S. Treatment of stable and recalcitrant vitiligo by autologous

miniature punch grafting: a prospective study of 1,000 patients. Dermatology

1999; 198:133.

73. Singh SK. Punch grafting in vitiligo : Refinements and case selection. Indian J

Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1997; 63:296.

74. Kato H, Furuhashi T, Ito E, et al. Efficacy of 1-mm minigrafts in treating vitiligo

depends on patient age, disease site and vitiligo subtype. J Dermatol 2011;

38:1140.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 26 of 29

75. Al-Mutairi N, Manchanda Y, Al-Doukhi A, Al-Haddad A. Long-term results of split-

skin grafting in combination with excimer laser for stable vitiligo. Dermatol Surg

2010; 36:499.

76. Khandpur S, Sharma VK, Manchanda Y. Comparison of minipunch grafting versus

split-skin grafting in chronic stable vitiligo. Dermatol Surg 2005; 31:436.

77. Chen YF, Yang PY, Hu DN, et al. Treatment of vitiligo by transplantation of

cultured pure melanocyte suspension: analysis of 120 cases. J Am Acad

Dermatol 2004; 51:68.

78. Guerra L, Primavera G, Raskovic D, et al. Erbium:YAG laser and cultured

epidermis in the surgical therapy of stable vitiligo. Arch Dermatol 2003; 139:1303.

79. Budania A, Parsad D, Kanwar AJ, Dogra S. Comparison between autologous

noncultured epidermal cell suspension and suction blister epidermal grafting in

stable vitiligo: a randomized study. Br J Dermatol 2012; 167:1295.

80. Thakur P, Sacchidanand S, Nataraj HV, Savitha AS. A Study of Hair Follicular

Transplantation as a Treatment Option for Vitiligo. J Cutan Aesthet Surg 2015;

8:211.

81. Vinay K, Dogra S, Parsad D, et al. Clinical and treatment characteristics

determining therapeutic outcome in patients undergoing autologous non-cultured

outer root sheath hair follicle cell suspension for treatment of stable vitiligo. J Eur

Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015; 29:31.

82. Mapar MA, Safarpour M, Mapar M, Haghighizadeh MH. A comparative study of

the mini-punch grafting and hair follicle transplantation in the treatment of

refractory and stable vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 70:743.

83. Mulekar SV, Isedeh P. Surgical interventions for vitiligo: an evidence-based

review. Br J Dermatol 2013; 169 Suppl 3:57.

84. Gupta D, Kumari R, Thappa DM. Depigmentation therapies in vitiligo. Indian J

Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2012; 78:49.

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 27 of 29

85. Tan ES, Sarkany R. Topical monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone is an effective and

safe treatment for depigmentation of extensive vitiligo in the medium term: a

retrospective cohort study of 53 cases. Br J Dermatol 2015; 172:1662.

86. Grimes PE, Hamzavi I, Lebwohl M, et al. The efficacy of afamelanotide and

narrowband UV-B phototherapy for repigmentation of vitiligo. JAMA Dermatol

2013; 149:68.

87. Lim HW, Grimes PE, Agbai O, et al. Afamelanotide and narrowband UV-B

phototherapy for the treatment of vitiligo: a randomized multicenter trial. JAMA

Dermatol 2015; 151:42.

88. Graham A, Westerhof W, Thody AJ. The expression of alpha-MSH by

melanocytes is reduced in vitiligo. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999; 885:470.

89. Kapoor R, Phiske MM, Jerajani HR. Evaluation of safety and efficacy of topical

prostaglandin E2 in treatment of vitiligo. Br J Dermatol 2009; 160:861.

90. Kapur R, Osmanovic S, Toyran S, Edward DP. Bimatoprost-induced periocular

skin hyperpigmentation: histopathological study. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;

123:1541.

91. Narang G. Efficacy and Safety of Topical Bimatoprost Solution 0.03% in Stable Viti

ligo: A Prelliminary Study. World Congress of Dermatology Seoul, Korea, June 20

11.

92. Grimes PE. Bimatoprost 0.03% Solution for the Treatment of Nonfacial Vitiligo. J

Drugs Dermatol 2016; 15:703.

93. Rothstein B, Joshipura D, Saraiya A, et al. Treatment of vitiligo with the topical

Janus kinase inhibitor ruxolitinib. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017.

94. Papadopoulos L, Bor R, Legg C. Coping with the disfiguring effects of vitiligo: a

preliminary investigation into the effects of cognitive-behavioural therapy. Br J

Med Psychol 1999; 72 ( Pt 3):385.

95. Mu EW, Cohen BE, Orlow SJ. Early-onset childhood vitiligo is associated with a

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 28 of 29

more extensive and progressive course. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 73:467.

96. Betterle C, Caretto A, De Zio A, et al. Incidence and significance of organ-specific

autoimmune disorders (clinical, latent or only autoantibodies) in patients with

vitiligo. Dermatologica 1985; 171:419.

Topic 106619 Version 5.0

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vitiligo-management-an…=1~138&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4264468486 09/07/19, 10L47 AM

Page 29 of 29

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Meeting The Physical Therapy Needs of Children - Effgen, Susan K. (SRG)Document797 paginiMeeting The Physical Therapy Needs of Children - Effgen, Susan K. (SRG)bizcocho4100% (7)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Myeloproliferative Disorders PDFDocument52 paginiMyeloproliferative Disorders PDFBoneyJalgar100% (3)

- Short Answer Questions AnaesthesiaDocument91 paginiShort Answer Questions AnaesthesiaMeena Ct100% (11)

- Biliary Tract Disease - Emmet AndrewsDocument52 paginiBiliary Tract Disease - Emmet AndrewsBoneyJalgarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why I Desire to Study Medical MicrobiologyDocument2 paginiWhy I Desire to Study Medical MicrobiologyRobert McCaul100% (1)

- Vertigo and Dizziness Guide for Healthcare ProvidersDocument50 paginiVertigo and Dizziness Guide for Healthcare ProvidersAu Ah Gelap100% (1)

- Obstetric Analgesia PDFDocument45 paginiObstetric Analgesia PDFBoneyJalgar100% (1)

- CCN (Feu)Document71 paginiCCN (Feu)Ashley Nicole Lim100% (1)

- McKee's pathology of the skinDocument1 paginăMcKee's pathology of the skinBoneyJalgarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biliary Tumors: Cholangiocarcinoma and Cancer of The Gall BladderDocument34 paginiBiliary Tumors: Cholangiocarcinoma and Cancer of The Gall BladderBoneyJalgarÎncă nu există evaluări

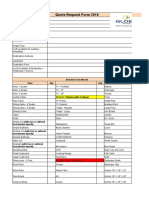

- Quote Request Form 2018: Articles To Be Moved Item Qty QtyDocument6 paginiQuote Request Form 2018: Articles To Be Moved Item Qty QtyBoneyJalgarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Form 1Document3 paginiForm 1BoneyJalgarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biliary Tumors: Cholangiocarcinoma and Cancer of The Gall BladderDocument34 paginiBiliary Tumors: Cholangiocarcinoma and Cancer of The Gall BladderBoneyJalgarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ectopic Features. 123 - RecoveredDocument13 paginiEctopic Features. 123 - RecoveredBoneyJalgarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Form 1Document3 paginiForm 1BoneyJalgarÎncă nu există evaluări

- InstructionsDocument1 paginăInstructionsnishtha_singhal_drÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ectopic Features. 123 - RecoveredDocument13 paginiEctopic Features. 123 - RecoveredBoneyJalgarÎncă nu există evaluări

- 27831Document20 pagini27831BoneyJalgarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classifying The Illness in Young Infants ( 2Mths)Document9 paginiClassifying The Illness in Young Infants ( 2Mths)BoneyJalgarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anesthesia and Analgesia in ObstetricsDocument45 paginiAnesthesia and Analgesia in ObstetricsBoneyJalgarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anesthesia and Analgesia in ObstetricsDocument45 paginiAnesthesia and Analgesia in ObstetricsBoneyJalgarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prevention & Early Outpatient Treatment Protocol For Covid-19Document4 paginiPrevention & Early Outpatient Treatment Protocol For Covid-19jack mehiffÎncă nu există evaluări

- RLE Manual EditedDocument68 paginiRLE Manual EditedReymondÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental Status Examination - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument9 paginiMental Status Examination - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfGRUPO DE INTERES EN PSIQUIATRIAÎncă nu există evaluări

- CONCEPT EpidemilologyDocument13 paginiCONCEPT EpidemilologyKrishnaveni MurugeshÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Analysis of Ethical Issues in Pharmaceutical IndustryDocument19 paginiAn Analysis of Ethical Issues in Pharmaceutical IndustrySuresh KodithuwakkuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lily Grebe Resume 10Document3 paginiLily Grebe Resume 10api-482765948Încă nu există evaluări

- Arterial Disorders: Arteriosclerosis & AtherosclerosisDocument28 paginiArterial Disorders: Arteriosclerosis & AtherosclerosisManuel Jacob YradÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shalini Tummala ResumeDocument2 paginiShalini Tummala Resumeapi-385467850Încă nu există evaluări

- Tinnitus Today December 1998 Vol 23, No 4Document29 paginiTinnitus Today December 1998 Vol 23, No 4American Tinnitus AssociationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Food Safety Case - The Fat Duck Norovirus Outbreak, UK - 2009Document16 paginiFood Safety Case - The Fat Duck Norovirus Outbreak, UK - 2009OPGJrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reducing the Risk of Infection in Diabetic PatientsDocument7 paginiReducing the Risk of Infection in Diabetic PatientsAnn Michelle TarrobagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Doença Celiaca GuidelinesDocument45 paginiDoença Celiaca Guidelinesleonardo mocitaibaÎncă nu există evaluări

- CV DR Shilpa Kalra 2021Document10 paginiCV DR Shilpa Kalra 2021Shilpa Kalra TalujaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fading Kitten Emergency Protocol: Hypothermia HypoglycemiaDocument1 paginăFading Kitten Emergency Protocol: Hypothermia HypoglycemiaJose Emmanuel MÎncă nu există evaluări

- IsmailDocument9 paginiIsmailapi-547285914Încă nu există evaluări

- Single-payer health care reduces inequality gapsDocument52 paginiSingle-payer health care reduces inequality gapsMetelitswagÎncă nu există evaluări

- Catalogue Rudolf - Instrument Surgical - PT. Graha IsmayaDocument172 paginiCatalogue Rudolf - Instrument Surgical - PT. Graha IsmayayuketamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (14374331 - Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM) ) Measurement Uncertainty - Light in The ShadowsDocument3 pagini(14374331 - Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM) ) Measurement Uncertainty - Light in The ShadowsJulián Mesa SierraÎncă nu există evaluări

- CHF SIM - Preparation Questions and Notes For LPN StudentsDocument3 paginiCHF SIM - Preparation Questions and Notes For LPN Studentsmercy longÎncă nu există evaluări

- List Cebu AFFIL PHYSICIANS1 (Wo Neuro) - As of 09012011Document6 paginiList Cebu AFFIL PHYSICIANS1 (Wo Neuro) - As of 09012011Irish BalabaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discharge PlanDocument4 paginiDischarge PlanPaul Loujin LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Vs Alteplase For Patients With Minor NondisablingDocument10 paginiDual Antiplatelet Therapy Vs Alteplase For Patients With Minor Nondisablingbetongo Bultus Ocultus XVÎncă nu există evaluări

- CT AuditsDocument53 paginiCT Auditsapi-3810976Încă nu există evaluări

- Chemoregimen - Testicular CancerDocument2 paginiChemoregimen - Testicular CancerNanda Asyura RizkyaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal Ebn Managemen 1Document7 paginiJurnal Ebn Managemen 1KohakuÎncă nu există evaluări