Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

2 Standard Vacuum Oil PDF

Încărcat de

KEMP0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

5 vizualizări11 paginiTitlu original

2 standard vacuum oil.pdf

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

5 vizualizări11 pagini2 Standard Vacuum Oil PDF

Încărcat de

KEMPDrepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 11

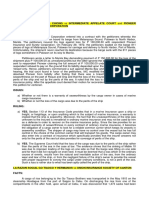

[No. L-5203.

April 18, 1956]

STANDARD VACUUM OIL COMPANY, plaintiff and

appellant, vs. LUZON STEVEDORING Co., INC.,

defendant and appellee.

CARRIERS; MERCHANDISE TRANSPORTED AT

RISK OF SHIPPERS; WHEN SHIPOWNER LIABLE.—

Under Article 361 of the Code of Commerce, merchandise

transported in the sea by virtue of a contract entered into

between the shipper and the carrier, is deemed transported

at the risk and venture of the shipper, if the contrary is not

stipulated, and all damages suffered by the merchandise

during the transportation by reason of accident or force

majeure shall be for the account and risk of the shipper, but

the proof of these accidents is incumbent on the carrier. In

the present case, the gasoline was delivered in accordance

with the contract but defendant failed to transport it to its

place of destination, not because of accident or force majeure

or cause beyond its control, but due to the unseaworthiness

of the tugboat towing the barge carrying the gasoline, lack of

necessary spare parts on board, and deficiency or

incompetence in the man power of the tugboat. The loss was

also caused because the defendant did not have in readiness

any tugboat sufficient in tonnage and equipment to attend to

the rescue. Under the circumstances, defendant is not

exempt from liability under the law.

APPEAL from a judgment of the Court of First

Instance of Manila. San Jose, J.

The facts are stated in the opinion of the Court.

Ross, Selph, Carrascoso & Janda and Martin B.

Laurea for appellant.

Perkins, Ponce Enrile & Contreras for appellee.

818

818 PHILIPPINE REPORTS ANNOTATED

Standard Vacuum Oil Co. vs. Luzon Stevedoring Co.,

Inc.

BAUTISTA ANGELO, J.:

Plaintiff entered into a contract with defendant to

transport between the ports of Manila and Nin Bay,

Sagay, Iloilo, 2,916.44 barrels of bulk gasoline

belonging to plaintiff. The gasoline was delivered in

accordance with the contract but defendant failed to

transport it to its place of destination and so plaintiff

brought this action in the Court of First Instance of

Manila to recover the sum of P75,578.50 as damages.

Defendant, in its answer, pleaded that its failure to

deliver the gasoline was due to fortuitous event or

caused by circumstances beyond its control and not to

its fault or negligence or that of any of its employees.

The court, after receiving the evidence, rendered

decision finding that the disaster that had befallen the

tugboat was the result of an unavoidable accident and

the loss of the gasoline was due to a fortuitous even

which was beyond the control of defendant and,

consequently, dismissed the case with costs against the

plaintiff.

The facts as found by the trial court are: “that

pursuant to an agreement had between the parties,

defendant’s barge No. L-522 was laden with gasoline

belonging to the plaintiff to be transported from

Manila to the Port of Iloilo; that early in the morning

of February 2, 1947, defendant’s tugboat “Snapper’

picked up the barge outside the breakwater; that the

barge was placed behind the tugboat, it being

connected to the latter by a tow rope ten inches in

circumference; that behind the barge, three other

barges were likewise placed, one laden with some cargo

while the other two containing hardly any cargo at all;

that the weather was good when on that day the

tugboat with its tow started on its voyage; that the

weather remained good on February 3, 1947, when it

passed Santiago Point in Batangas; that at about 3:00

o’clock in the morning of February 4, 1947, the engine

of the tugboat came to a dead stop; that the engineer

on board

819

VOL. 98, APRIL 18, 1956 819

Standard Vacuum Oil Co. vs. Luzon Stevedoring Co.,

Inc.

the tugboat found out that the trouble was due to a

broken idler; that a message was then sent to the

defendant’s radio station in Manila informing its

officials of the engine trouble; that upon the receipt of

the message the defendant called up several shipping

companies in Manila to find out if they had any vessels

in the vicinity where the “Snapper’ had stalled but said

companies replied in the negative; that thereupon the

defendant radioed its tugboat ‘Tamban’ which was

docked at Batangas, ordering it to proceed to the place

where the ‘Snapper’ was; that at about 6:00 o’clock in

the same morning of February 4, 1947, the master of

the ‘Snapper’ attempted to cast anchor but the water

areas around Elefante Island were so deep that the

anchor did not touch bottom; that in the afternoon of

the same day the weather become worse as the wind

increased in intensity and the waves were likewise

increased in size and force; that due to the rough

condition of the sea the anchor chains of the ‘Snapper’

and the four barges broke one by one and as a

consequence thereof they were drifted and were finally

dashed against the rocks off Banton Island; that on

striking the rocks a hole was opened in the hull of the

‘Snapper’, which ultimately caused it to sink, while the

barge No. L-522 was so badly damaged that the

gasoline it had on board leaked out; and that the

‘Tamban’ arrived at the place after the gasoline had

already leaked out.”

Defendant is a private stevedoring company

engaged in transporting local products, including

gasoline in bulk and has a fleet of about 140 tugboats

and about 90 per cent of its business is devoted to

transportation. Though it is engaged in a limited

contract of carriage in the sense that it chooses its

customers and is not opened to the public.

nevertheless, the continuity of its operations in this

kind of business have earned for it the level of a public

utility. The contract between the plaintiff and

defendant comes therefore under the provisions of the

820

320 PHILIPPINE REPORTS ANNOTATED

Standard Vacuum Oil Co. vs. Luzon Stevedoring Co.,

Inc.

Code of Commerce. The pertinent law is article 361

which provides:

“ART. 361. The merchandise shall be transported at the risk

and venture of the shipper, if the contrary was not expressly

stipulated.

“Therefore, all damages and impairment suffered by the

goods during the transportation, by reason of accident, force

majeure, or by virtue of the nature or defect of the articles,

shall be for the account and risk of the shipper.

“The proof of these accidents is incumbent on the carrier.”

It therefore appears that whenever merchandise is

transported on the sea by virtue of a contract entered

into between the shipper and the carrier, the

merchandies is deemed transported at the risk and

venture of the shipper, if the contrary is not stipulated,

and all damages suffered by the merchandise during

the transportation by reason of accident or force

majeure shall be for the account and risk of the

shipper, but the proof of these accidents is incumbent

on the carrier. Implementing this provision, our

Supreme Court has held that all a shipper has to prove

in connection with sea carriage is delivery of the

merchandise in good condition and its non-delivery at

the place of destination in order that the burden of

proof may shift to the carrier to prove any of the

accidents above adverted to. Thus, it was held that

“Shippers who are forced to ship goods on an ocean

liner or any other ship have some legal rights, and

when goods are delivered on board a ship in good order

and condition, and the shipowner delivers them to the

shipper in bad order and condition, it then devolves

upon the shipowner to both allege and prove that the

goods were damaged by reason of some fact which

legally exempts him from liability” (Mirasol vs. Robert

Dollar Co., 53 Phil., 129).

The issue to be determined is: Has defendant proven

that its failure to deliver the gasoline to its place of

destination is due to accident or force majeure or to a

cause beyond its control? This would require an

analysis of

821

VOL. 98, APRIL 18, 1956 821

Standard Vacuum Oil Co. vs. Luzon Stevedoring Co.

the facts and circumstances surrounding the

transportation of said gasoline.

It appears that the tugboat “Snapper” was acquired

by defendant from the Foreign Liquidation

Commission. It was a surplus property. It was a deep-

sea tugboat that had been in the service of the United

States Armed Forces prior to its purchase by the Luzon

Stevedoring Co. The tugboat was put into operation

without first submitting it to an overhaul in a dry-

dock. It also appears that this tugboat had previously

made several trips and each time it had to obtain a

special permit from the Bureau of Customs because it

had never been dry-docked and did not have complete

equipment to be able to obtain a permanent permit.

The special permits that were issued by said Bureau

specifically state that they were issued “pending

submission of plans and load line certificate, including

test and final inspection of equipment.” It further

appears that, when the tugboat was inspected by the

Bureau of Customs on October 18, 1946, it found it to

be inadequately equipped and so the Bureau required

defendant to provide it with the requisite equipment

but it was never able /to complete it. The fact that the

tugboat was a surplus property, has not been dry-

docked, and was not provided with the requisite

equipment to make it seaworthy, shows that defendant

did not use reasonable diligence in putting the tugboat

in such a condition as would make its use safe for

operation. It is true, as defendant contends, that there

were then no dry-dock facilities in the Philippines, but

this does not mean that they could not be obtained

elsewhere, It being a surplus property, a dry-dock

inspection was a must to put the tugboat in a sea going

condition. It may also be true, as contended, that the

deficiency in the equipment was due to the fact that no

such equipment was available at the time, but this did

not justify defendant in putting such tugboat in

business even if unequipped merely to make a profit.

Nor could the fact that the tugboat was

822

822 PHILIPPINE REPORTS ANNOTATED

Standard Vacuum Oil Co. vs. Luzon Stevedoring Co.,

Inc.

given a special permit by the Bureau of Customs to

make the trip relieve defendant from liability.

“Where owner buys old tug, licensed coastwise, and equips it

for ocean going, it is negligence to send tug out without

knowing something of her stability and especially without

stability test, where history and performance with respect to

crankiness and tenderness are matters of official record.

Sabine Towing Co. vs. Brennan, C.C. A. Tex., 72 F 2d 490,

certiorari denied 55 S. Ct. 141, 293 U.S. 611, 79 L. Ed. 701,

rehearing denied 55 S. Ct. 212, 293 U.S. 632, 79 L. Ed. 717."

(80 C.J. S. 803 Footnote)

There are other circumstances which show the lack of

precaution and diligence taken by defendant to make

the travel of the tugboat safe. One is the failure to

carry on board the necessary spare parts. When the

idler was broken, the engineer of the tugboat examined

it for the first time and it was only then that he found

that there were no spare parts to use except a worn out

spare driving chain. And the necessity of carrying such

spare parts was emphasized by the very defendant’s

witness, Mr. Depree, who said that in vessels motored

by diesel engines it is necessary always to carry spare

chains, ball bearings and chain drives. And this was

not done.

“A tug engaged to tow a barge is liable for damage to the

cargo of the barge caused by faulty equipment of the tug. The

Raleigh, D.C. Md. 50 F. Supp. 961." (80 C.J. S. Footnote.)

Another circumstance refers to the deficiency OF

incompetence in the man power of the tugboat.

According to law, a tugboat of the tonnage and powers

of one like the “Snapper” is required to have a

complement composed of one first mate, one second

mate, one third mate, one chief engineer, one second

engineer, and one third engineer, (section 1203,

Revised Administrative Code), but when the trip in

question was undertaken, it was only manned by one

master, who was merely licensed as a bay, river, and

lake patron, one second mate, who was licensed as a

third mate, one chief engineer who was licensed as

third motor engineer, one assistant engineer, who was

licensed as a bay, river, and lake motor engineer, and

one second assistant engineer, who was un-

823

VOL. 98, APRIL 18, 1956 823

Standard Vacuum Oil Co. vs. Luzon Stevedoring Co.,

Inc.

licensed. The employment of this crew to perform

functions beyond its competence and qualifications is

not only risky but against the law and if a mishap is

caused, as in this case, one cannot but surmise that

such incompetence has something to do with the

mishap. The fact that the tugboat had undertaken

several trips before with practically the same crew

without any untoward consequence, cannot furnish

any justification for continuing in its employ a

deficient or incompetent personnel contrary to law and

the regulations of the Bureau of Customs.

"(1) Generally, seaworthiness is that strength, durability and

engineering skill made a part of a ship’s construction and

continued maintenance, together with a competent and

sufficient crew, which would withstand the vicissitudes and

dangers of the elements which might reasonably be expected

or encountered during her voyage without loss or damage to

her particular cargo. The Cleveco, D.C. Ohio, 59 F. Supp. 71,

78, affirmed, C.C. A., 154 F. 2d 606." (80 C.J. S. 997,

Footnote.)

Let us now come to the efforts exerted by defendant in

extending help to the tugboat when it was notified of

the breakage of the idler. The evidence shows that the

idler was broken at about 3:00 o’clock in the morning of

February 4, 1947. Within a few minutes, a message

was sent to defendant by radio informing it of the

engine trouble. The weather was good at the time and

the sea was smooth, and remained good until 12:00

o’clock noon when the wind started to blow. According

to defendant, since it received the message, it called up

different shipping lines in Manila asking them if they

had any vessel in the vicinity where the “Snapper”

stalled but, unfortunately, none was available at the

time, and as its tug “Tamban” was then docked in

Batangas, Batangas, which was nearest to the place, it

radioed said tug to go to the aid of the “Snapper”.

Accordingly, the tug “Tamban” set sail from Batangas

for the rescue only to return to secure a map of the

vicinity where the “Snapper” had stalled, which

entailed a delay of two hours.

824

824 PHILIPPINE REPORTS ANNOTATED

Standard Vacuum Oil Co. vs. Luzon Stevedoring Co.,

Inc.

In the meantime, the captain of the “Snapper”

attempted to east anchor. The water areas off Elefante

Island were deep and the anchor would not touch

bottom. Then the sea became rough and the waves

increased in size and force and notwithstanding the

efforts of the crew to prevent the tug from drifting

away, the force of the wind and the violence of the

waves dashed the tug and the barges against the rocks.

The tug developed a hole in her hull and sank. The

barge carrying the gasoline was so badly damaged that

the gasoline leaked out. The tug “Tamban” was finally

able to locate the “Snapper” but it was too late.

The foregoing acts only serve to emphasize that the

efforts made by defendant fall short of that diligence

and precaution that are demanded by the situation to

save’ the tugboat and the barge it was towing from

disaster for it appears that more than twenty-four

hours had elapsed before the tug “Tamban” showed up

to extend help. The delay was caused not so much

because of the lack of available ships in the vicinity

where the “Snapper” stalled but because defendant did

not have in readiness any tugboat sufficient in tonnage

and equipment to attend to the rescue. The tug

“Tamban” that was ordered to extend help was fully

inadequate for that purpose. It was a small vessel that

was authorized to operate only within Manila Bay and

did not even have any map of the Visayan Islands. A

public utility that is engaged in sea transportation

even for a limited service with a fleet of 140 tugboats

should have a competent tug to rush for towing or

repairs in the event of untoward happening overseas.

If defendant had only such a tug ready for such an

emergency, this disaster would not have happened.

Defendant could have avoided sending a poorly

equipped tug which, as it is to be expected, f ailed to do

job.

While the breaking of the idler may be due to an

accident, or to something unexpected, the cause of the

disaster which resulted in the loss of the gasoline can

only be attributed to the negligence or lack of

precaution

825

VOL. 98, APRIL 18, 1956 825

Phil. Air Lines, Inc. vs. Prieto, et at.

to avert it on the part of defendant. Defendant had

enough time to effectuate the rescue if it had only a

competent tug for the purpose because the weather

was good from 3:00 o’clock a.m. to 12:00 o’clock noon of

February 4, 1947 and it was only in the afternoon

1

that

the wind began to blow with some intensity, but failed

to do so because of that shortcoming. The loss of the

gasoline certainly cannot be said to be due to force

majeure or unforeseen event but to the failure of

defendant to extend adequate and proper help.

Considering these circumstances, and those we have

discussed elsewhere, we are persuaded to conclude

that defendant has failed to establish that it is exempt

from liability under the law.

Wherefore, the decision appealed from is reversed.

Defendant is hereby ordered to pay to plaintiff the sum

of P75,578.50, with legal interest from the date of the

filing of the complaint, with costs.

Parás, C.J., Bengzon, Padilla, Montemayor, Reyes,

A., Jugo, Labrador, Concepcion, Reyes, J.B. L., and

Endencia, JJ., concur.

Judgment reversed.

_____________

© Copyright 2020 Central Book Supply, Inc. All rights reserved.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shipping Practice - With a Consideration of the Law Relating TheretoDe la EverandShipping Practice - With a Consideration of the Law Relating TheretoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Report on State of the Colony of New South WalesDe la EverandReport on State of the Colony of New South WalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Standard Vacuum Oil Co. vs. Luzon Stevedoring Co., Inc.Document5 paginiStandard Vacuum Oil Co. vs. Luzon Stevedoring Co., Inc.Dorky DorkyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2 Standard Vacuum OilDocument5 pagini2 Standard Vacuum OilMary Louise R. ConcepcionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Standard Vacuum Oil v. Luzon StevedoringDocument6 paginiStandard Vacuum Oil v. Luzon StevedoringLorelei B RecuencoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Standard Vacuum Oil Company Vs Luzon Stevedoring Co. Inc.Document5 paginiStandard Vacuum Oil Company Vs Luzon Stevedoring Co. Inc.Edgardo MimayÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. L-5203 April 18, 1956 STANDARD VACUUM OIL COMPANY, Plaintiff-Appellant, vs. LUZON STEVEDORING CO., INC., Defendant-AppelleeDocument50 paginiG.R. No. L-5203 April 18, 1956 STANDARD VACUUM OIL COMPANY, Plaintiff-Appellant, vs. LUZON STEVEDORING CO., INC., Defendant-AppelleeRajane Alexandra DequitoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Standard Vacuum Oil vs. Luzon Stevedoring G.R. No. L-5203, April 18, 1956 DoctrineDocument23 paginiStandard Vacuum Oil vs. Luzon Stevedoring G.R. No. L-5203, April 18, 1956 DoctrineFaye de LeonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transpo Case DigestDocument13 paginiTranspo Case DigestHoney GuideÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tabacalera Insurance Co. v. North Front Shipping ServicesDocument5 paginiTabacalera Insurance Co. v. North Front Shipping ServicessophiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 24 Tabacalera Insurance Vs North Front ShippingDocument6 pagini24 Tabacalera Insurance Vs North Front ShippingLeo TumaganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tabacalera Insurance Co. v. North Front Shipping Services Inc.Document2 paginiTabacalera Insurance Co. v. North Front Shipping Services Inc.Mikee RañolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Digest: Magsaysay Inc. vs. AganDocument7 paginiCase Digest: Magsaysay Inc. vs. AganMarj MariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transportation Law Case Digests-FRANCISCODocument15 paginiTransportation Law Case Digests-FRANCISCOZesyl Avigail FranciscoÎncă nu există evaluări

- ExtraordinaryDocument25 paginiExtraordinaryCE SherÎncă nu există evaluări

- Insurance Finals Week 5 Isabela Roque and Ong Chiong Vs Intermediate Appelate Court and Pioneer Insurance and Surety Corporation FactsDocument9 paginiInsurance Finals Week 5 Isabela Roque and Ong Chiong Vs Intermediate Appelate Court and Pioneer Insurance and Surety Corporation FactslckdsclÎncă nu există evaluări

- TABACALERA INSURANCE CO v. NORTH FRONT SHIPPINGDocument2 paginiTABACALERA INSURANCE CO v. NORTH FRONT SHIPPINGAlphaZuluÎncă nu există evaluări

- DigestDocument4 paginiDigestAlyssa Mae BasalloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adalisay Transpo Cases 1st BatchDocument4 paginiAdalisay Transpo Cases 1st BatchArman DalisayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tabacalera Insurance Co. Vs North Front Shipping, Inc.Document10 paginiTabacalera Insurance Co. Vs North Front Shipping, Inc.Rhona MarasiganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Loadstar v. Pioneer DIGESTDocument3 paginiLoadstar v. Pioneer DIGESTkathrynmaydeveza100% (1)

- Tabacalera V NorthfrontDocument3 paginiTabacalera V NorthfrontJoyceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reviewer On Transport CasesDocument2 paginiReviewer On Transport CasesIyah RoblesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transpo DigestDocument15 paginiTranspo DigestPraisah Marjorey Casila-Forrosuelo PicotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Loadstar Shipping vs. CADocument4 paginiLoadstar Shipping vs. CABen EncisoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 26 Tabacalera Vs North FrontDocument6 pagini26 Tabacalera Vs North FrontMary Louise R. ConcepcionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transpo Feb 14 CasesDocument4 paginiTranspo Feb 14 CasesDanielleÎncă nu există evaluări

- GR No 119197 Tabacalera Insurance Co V North FrontDocument3 paginiGR No 119197 Tabacalera Insurance Co V North FrontruelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Loadstar V Pioneer GDocument2 paginiLoadstar V Pioneer GAnsis Villalon PornillosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Loadstar Shipping Co., Inc., V. Pioneer Asia Insurance Corp.Document2 paginiLoadstar Shipping Co., Inc., V. Pioneer Asia Insurance Corp.Joshua OuanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- LOADSTAR SHIPPING CO., INC., Petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS and THE MANILA INSURANCE CO., INC., Respondents.Document4 paginiLOADSTAR SHIPPING CO., INC., Petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS and THE MANILA INSURANCE CO., INC., Respondents.lexxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eastern Shipping Vs CADocument5 paginiEastern Shipping Vs CAdlo dphroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tabacalera Insurance Co., vs. North Front Shipping Services, IncDocument2 paginiTabacalera Insurance Co., vs. North Front Shipping Services, IncNash LedesmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- National Steel Corporation V. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 112287 December 12, 1997 Panganiban, J. DoctrineDocument23 paginiNational Steel Corporation V. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 112287 December 12, 1997 Panganiban, J. DoctrineDiane Erika Lopez ModestoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eastern Shipping Lines, Inc. Vs IACDocument15 paginiEastern Shipping Lines, Inc. Vs IACDarwin SolanoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case DigestDocument36 paginiCase DigestmendozaimeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Planters Products Vs CADocument2 paginiPlanters Products Vs CAeieipayadÎncă nu există evaluări

- IV. Transportation A. Common Carriers: FactsDocument13 paginiIV. Transportation A. Common Carriers: FactsJohnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transpo - 2Document60 paginiTranspo - 2YsabelleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Central Shipping Company Vs Insurance Company of North America Case DigestDocument20 paginiCentral Shipping Company Vs Insurance Company of North America Case DigestJoshua ParilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Central Shipping Company Vs Insurance Company of North America Case DigestDocument36 paginiCentral Shipping Company Vs Insurance Company of North America Case DigestJoshua ParilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Central Shipping Company Vs Insurance Company of North America Case DigestDocument43 paginiCentral Shipping Company Vs Insurance Company of North America Case DigestJoshua ParilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Central Shipping Company Vs Insurance Company of North America Case DigestDocument60 paginiCentral Shipping Company Vs Insurance Company of North America Case DigestJoshua ParilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Central Shipping Company Vs Insurance Company of North America Case DigestDocument13 paginiCentral Shipping Company Vs Insurance Company of North America Case DigestJoshua ParilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Central Shipping Company Vs Insurance Company of North America Case DigestDocument21 paginiCentral Shipping Company Vs Insurance Company of North America Case DigestJoshua ParilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Central Shipping Company Vs Insurance Company of North America Case DigestDocument60 paginiCentral Shipping Company Vs Insurance Company of North America Case DigestJoshua ParilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Central Shipping Company Vs Insurance Company of North America Case DigestDocument12 paginiCentral Shipping Company Vs Insurance Company of North America Case DigestJoshua ParilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roque V Iac - Atienza-F (d2017)Document2 paginiRoque V Iac - Atienza-F (d2017)Kulit_Ako1Încă nu există evaluări

- 89 Ynchausti Steamship Co. v. DexterDocument2 pagini89 Ynchausti Steamship Co. v. DexterAnn Julienne AristozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asia Lighterage & Shipping Vs CADocument3 paginiAsia Lighterage & Shipping Vs CAShierii_ygÎncă nu există evaluări

- Common Carriers DigestDocument9 paginiCommon Carriers DigestAaliyahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coastwise V CADocument2 paginiCoastwise V CAJaymar DetoitoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Santiago Lighterage v. Court of Appeals, SCRA, G.R. No. 139629, June 21, 2004.Document2 paginiSantiago Lighterage v. Court of Appeals, SCRA, G.R. No. 139629, June 21, 2004.Camille Tapec100% (1)

- Mirasol v. Dollar Bankers and Manufacturers v. CA RCL of Singapore v. TNIDocument11 paginiMirasol v. Dollar Bankers and Manufacturers v. CA RCL of Singapore v. TNIDon SumiogÎncă nu există evaluări

- Santiago Lighterage Corporation V CADocument2 paginiSantiago Lighterage Corporation V CACzar Ian Agbayani100% (2)

- Planters Products Vs CADocument6 paginiPlanters Products Vs CAFatima Sarpina HinayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transportation Law Digest Cases 1. Shewaram Vs PAL Case Digest Shewaram VS, Philippine Airlines (17 SCRA 606, (1966) FactsDocument16 paginiTransportation Law Digest Cases 1. Shewaram Vs PAL Case Digest Shewaram VS, Philippine Airlines (17 SCRA 606, (1966) FactsRhaj Łin KueiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Loadstar Vs CA GR No. 131621Document5 paginiLoadstar Vs CA GR No. 131621Anonymous KZEIDzYrOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ohta Vs Steamship PompeyDocument2 paginiOhta Vs Steamship PompeyXing Keet LuÎncă nu există evaluări

- TranspoDocument3 paginiTranspoRinielÎncă nu există evaluări

- BIO20-1 The Biological Cell and The BiomoleculesDocument7 paginiBIO20-1 The Biological Cell and The BiomoleculesKEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- BIO20 - Proteins PDFDocument22 paginiBIO20 - Proteins PDFKeith Ryan LapizarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Instrumental Figures Instruction4Document1 paginăInstrumental Figures Instruction4KEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- BIO20-1 Bioinformatics ModuleDocument11 paginiBIO20-1 Bioinformatics ModuleKEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Objective: L RMS L RMSDocument2 paginiObjective: L RMS L RMSKEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- BIO20-1 rDNA TechnologyDocument7 paginiBIO20-1 rDNA TechnologyKEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To BioelectronicsDocument46 paginiIntroduction To BioelectronicsKEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- GEAS ECE March 2018Document6 paginiGEAS ECE March 2018KEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- GEAS ECE March 2018Document6 paginiGEAS ECE March 2018KEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- x z 2 2 2 2 2 φ z 2 2 2 2 φ z 2 2 φ z 2 φ 2 2 zDocument6 paginix z 2 2 2 2 2 φ z 2 2 2 2 φ z 2 2 φ z 2 φ 2 2 zKEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- GEAS ECE March 2018Document6 paginiGEAS ECE March 2018KEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- GEAS ECE March 2018Document6 paginiGEAS ECE March 2018KEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- x z 2 2 2 2 2 φ z 2 2 2 2 φ z 2 2 φ z 2 φ 2 2 zDocument6 paginix z 2 2 2 2 2 φ z 2 2 2 2 φ z 2 2 φ z 2 φ 2 2 zKEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Geas-10 3Document15 paginiGeas-10 3KEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 1 Matter Atomic StructureDocument44 paginiLecture 1 Matter Atomic StructureKEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- GEAS ECE Apr 2018Document6 paginiGEAS ECE Apr 2018KEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solutions PDFDocument38 paginiSolutions PDFKEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chemical Bonding I: Basic ConceptsDocument75 paginiChemical Bonding I: Basic ConceptsKEMP100% (1)

- Energy and PotentialDocument103 paginiEnergy and PotentialKEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Solutions PDFDocument38 paginiSolutions PDFKEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ch08 LectureDocument20 paginiCh08 LectureDeanÎncă nu există evaluări

- FLOWCHART OF TAX REMEDIES by Pierre Martin D. ReyesDocument11 paginiFLOWCHART OF TAX REMEDIES by Pierre Martin D. ReyesKEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 2 Electronic Structure of AtomsDocument72 paginiLecture 2 Electronic Structure of AtomsKEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gauss LawDocument36 paginiGauss LawKEMP100% (1)

- Spectrum Vs GraveDocument12 paginiSpectrum Vs GraveKEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moncupa vs. EnrileDocument8 paginiMoncupa vs. EnrileAnonymous RXWWzcqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Del Operator1Document89 paginiDel Operator1KEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- Differential Elements of Length, Surfaces, andDocument42 paginiDifferential Elements of Length, Surfaces, andKEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

- II Lahom v. SibuloDocument11 paginiII Lahom v. SibuloSahira Bint IbrahimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cercado VS UnipromDocument10 paginiCercado VS UnipromKEMPÎncă nu există evaluări

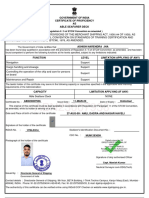

- Seafarer Profile Personal Details:::: SureshDocument5 paginiSeafarer Profile Personal Details:::: Sureshsuresh bekkantiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Operation RheinübungDocument3 paginiOperation RheinübungTashi SultanÎncă nu există evaluări

- FFG (X) Industry Day Brief FINALDocument15 paginiFFG (X) Industry Day Brief FINALBreakingDefense100% (1)

- Ashish Jha (Cop)Document1 paginăAshish Jha (Cop)ashishjha6067Încă nu există evaluări

- ISG Bulk Handling Brochure 13Document36 paginiISG Bulk Handling Brochure 13lucasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Challenges in Philippine Maritime Education and TrainingDocument10 paginiThe Challenges in Philippine Maritime Education and Trainingsimon soldevillaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seemp StudyDocument71 paginiSeemp StudyasdfightÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dwnload Full Essentials of Economics 8th Edition Mankiw Test Bank PDFDocument35 paginiDwnload Full Essentials of Economics 8th Edition Mankiw Test Bank PDFtedder.auscult.56jw100% (10)

- Halila Foresight SpecificationDocument5 paginiHalila Foresight SpecificationPriyanshu JoshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deepwater Reference BookDocument782 paginiDeepwater Reference BookCelso Guerrero Requena100% (2)

- PLAN's Type 22 Houbei FAC - July11 - R1Document44 paginiPLAN's Type 22 Houbei FAC - July11 - R1Steeljaw Scribe100% (5)

- Accomodation Requirements MLCDocument6 paginiAccomodation Requirements MLCLilik KhoiriyahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fish Capture ReviewerDocument2 paginiFish Capture ReviewerMark Joseph MurilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fatigue Analysis Method For LNG Membrane Tank Details: M. Huther, F. Benoit and J. Poudret, Bureau Veritas, Paris, FranceDocument12 paginiFatigue Analysis Method For LNG Membrane Tank Details: M. Huther, F. Benoit and J. Poudret, Bureau Veritas, Paris, FranceVilas AndhaleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sealion Oob and PlanningDocument7 paginiSealion Oob and PlanningRobert Silva SanchezÎncă nu există evaluări

- ABS Ship SFA Guide - e Dec07Document46 paginiABS Ship SFA Guide - e Dec07Advan ZuidplasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Load Line SurveysDocument2 paginiLoad Line SurveysBharatiyulam100% (2)

- Deck Oral Examination Syllabus FDocument4 paginiDeck Oral Examination Syllabus FRICROD71Încă nu există evaluări

- Appendix DDocument14 paginiAppendix D蓉蓉Încă nu există evaluări

- ts513 PDFDocument6 paginits513 PDFMung Duong XuanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Position PrepositionsDocument9 paginiPosition PrepositionsNarasinga Rao BarnikanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- GK PDFDocument14 paginiGK PDFManjeet SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Land ReclamationDocument48 paginiLand Reclamationprmanikkandan100% (5)

- Bridge 060 Log BookDocument2 paginiBridge 060 Log BookMiha MihaelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maritime AccidentDocument216 paginiMaritime AccidentȘtefan Stefan100% (2)

- Exercise 1a: Picture The SceneDocument9 paginiExercise 1a: Picture The SceneAlin NanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- TT 300 Ss A Installation ManualDocument54 paginiTT 300 Ss A Installation ManualArjunroyEdwardÎncă nu există evaluări

- Port DirectoryDocument30 paginiPort DirectoryMax WillÎncă nu există evaluări

- Construction PDFDocument238 paginiConstruction PDFmouloud miloudÎncă nu există evaluări

- 0809 UAS Ganjil Bahasa Inggris Kelas 8Document4 pagini0809 UAS Ganjil Bahasa Inggris Kelas 8Singgih Pramu Setyadi100% (8)