Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

India's Pre-Lockdown Data: A Flourish Chart

Încărcat de

Mohammad Khurram QureshiTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

India's Pre-Lockdown Data: A Flourish Chart

Încărcat de

Mohammad Khurram QureshiDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

By about 3:30 pm (IST) on April 14, the total number of confirmed COVID-19 cases neared 2 million

around the world, and deaths were about to exceed the 120,500 mark. But as if by a miracle, the

number of confirmed cases in India was just about 10,540, per official figures. Scepticism about this

unexpectedly low figure is often met with the refrain that it is thanks to containment efforts, although

the virus’s spread could have started in January itself.

The drastic limiting of social contacts and the nationwide lockdown may have played their intended

purpose – but they couldn’t have been adequate. Physical distancing norms and the nationwide

lockdown from March 25 were imposed unevenly across states, and the massive social and economic

disruption that followed couldn’t have helped.

This said, there are no known reasons for why the disease’s rate of spread appears to be lower in India.

Even so, it is difficult not to be sceptical of the official data. If we assume that the disease is nearly as

infectious as it seems to be in other geographies, why are the reported numbers so low? Is the actual

incidence not being captured in the data? Are there bottlenecks in the data-flow? Are there flaws in the

effort to assess the disease’s prevalence? Or are there other factors at work that obscure India’s efforts

to accurately determine the disease spread?

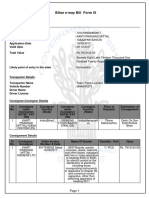

India’s pre-lockdown data

A Flourish chart

No airport-screening system can detect all infected persons. Until March 25, 2020, almost all of India’s

confirmed cases were related to air travel. A comparison of the airport traffic data and the cases

detected at airports points to large anomalies in the airport-screening programme and which can’t be

explained by minor variations.

On March 24, before the nationwide lockdown, India had 519 confirmed cases. Of this, if we take the

relative share of state-wise confirmed cases and compare them to air-passenger traffic through all

airports in each state (data of FY 2017-18), the discrepancies in airport-screening strategy will become

clear (see figure 1).

Delhi had 6% of the confirmed cases and accounted for 22% of passengers. West Bengal, Tamil Nadu

and Karnataka together accounted for 12% of confirmed cases and accounted for about 28% of

passengers. In contrast, Kerala accounted for 18% of confirmed cases but only 6% of passenger traffic.

This lack of pattern shows up the big differences in the effectiveness of airport-based screening and

contact-tracing. It also underscores the possibility that there are several times the number of

undetected cases as there are already detected cases, contributing to the disease’s spread.

A scientific paper published on February 24 shows that even in the best-

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- CTT 195 F 3 TQ 7 Yjex 6 by 8 WDocument11 paginiCTT 195 F 3 TQ 7 Yjex 6 by 8 Wsyeda taiba nooraniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tragic Errors in Leadership: Government's Reliance On Filipinos' Resiliency As ADocument3 paginiTragic Errors in Leadership: Government's Reliance On Filipinos' Resiliency As AGeojanni PangibitanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Disease Spread: Absent or Hidden?: Priyanka Pulla Wrote in The Wire ScienceDocument2 paginiDisease Spread: Absent or Hidden?: Priyanka Pulla Wrote in The Wire ScienceMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statistics of National Morbidity and MortalityDocument30 paginiStatistics of National Morbidity and MortalityKrystel Mae GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Machine Learning Problem in COVID SituationDocument5 paginiMachine Learning Problem in COVID SituationArcha ShajiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact of Population Density On Covid 19 Infected and Mortality Rate in IndiaDocument7 paginiImpact of Population Density On Covid 19 Infected and Mortality Rate in IndiaGiselle PeachÎncă nu există evaluări

- Balakrishnan-Namboodhiry2021 Article TheImportanceOfInvestingInAPubDocument22 paginiBalakrishnan-Namboodhiry2021 Article TheImportanceOfInvestingInAPubAyush RanjanÎncă nu există evaluări

- PAHO - WHO Data - Annual Arbovirus Bulletin 2020Document16 paginiPAHO - WHO Data - Annual Arbovirus Bulletin 2020Analia UrueñaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stay at Home Works To Fight Against COVID 19 International Evidence From Google Mobility DataDocument12 paginiStay at Home Works To Fight Against COVID 19 International Evidence From Google Mobility DatachetanÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Interactive Dashboard For Real-Time Analytics and Monitoring of Covid-19 Outbreak in India: A Proof of ConceptDocument17 paginiAn Interactive Dashboard For Real-Time Analytics and Monitoring of Covid-19 Outbreak in India: A Proof of ConceptDhananjai yadavÎncă nu există evaluări

- Impact of COVID On Tourism of Rajasthan 1941117159Document16 paginiImpact of COVID On Tourism of Rajasthan 1941117159Peram Amarnath 7147Încă nu există evaluări

- How Effective Is India's Battle Against Covid-19 Pandemic?: Parag Nijhawan, Parminder Singh, Manish Kumar SinglaDocument12 paginiHow Effective Is India's Battle Against Covid-19 Pandemic?: Parag Nijhawan, Parminder Singh, Manish Kumar Singlascience worldÎncă nu există evaluări

- COVID 19IndianStates PDFDocument12 paginiCOVID 19IndianStates PDFApooÎncă nu există evaluări

- COVID 19IndianStates PDFDocument12 paginiCOVID 19IndianStates PDFApooÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ijrbm - Unexpected Ramifications of Corona Pandemic (Rizwan)Document7 paginiIjrbm - Unexpected Ramifications of Corona Pandemic (Rizwan)Impact JournalsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Report 11: Evidence of Initial Success For China Exiting COVID-19 Social Distancing Policy After Achieving ContainmentDocument8 paginiReport 11: Evidence of Initial Success For China Exiting COVID-19 Social Distancing Policy After Achieving ContainmentMadhav SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 28 Shailaja KanwarDocument12 pagini28 Shailaja KanwarAnonymous CwJeBCAXpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literature Review of Research Paper Graphic Era UniDocument3 paginiLiterature Review of Research Paper Graphic Era UniAbhisekh Razz PandeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2020 05 28 COVID19 Report 23 Version2Document37 pagini2020 05 28 COVID19 Report 23 Version2Natasha DadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effectiveness of Lockdown - v5Document19 paginiEffectiveness of Lockdown - v5gilbert2691Încă nu există evaluări

- We Publish Below The Fith Article of A Series of Five.: Covid-19: It's Impact On The Philippines - Part VDocument11 paginiWe Publish Below The Fith Article of A Series of Five.: Covid-19: It's Impact On The Philippines - Part VJennylyn BoiserÎncă nu există evaluări

- Report 30: The COVID-19 Epidemic Trends and Control Measures in Mainland ChinaDocument16 paginiReport 30: The COVID-19 Epidemic Trends and Control Measures in Mainland ChinaZhida ChengÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sociology PPT, 6th SemDocument9 paginiSociology PPT, 6th SemUtkarsh ShubhamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unshackling India: Hard Truths and Clear Choices for Economic RevivalDe la EverandUnshackling India: Hard Truths and Clear Choices for Economic RevivalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assingment On Impact of CovidDocument20 paginiAssingment On Impact of Covidprerna100% (1)

- Current AffairsDocument4 paginiCurrent AffairsSony SubudhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument6 paginiReview of Related LiteratureInelÎncă nu există evaluări

- COVID Report 21 August PDFDocument27 paginiCOVID Report 21 August PDFmanojkp33Încă nu există evaluări

- Covid 19.edited (1) .EditedDocument16 paginiCovid 19.edited (1) .EditedMORRIS ANUNDAÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Analysis of COVID-19 Mortality Underreporting BDocument14 paginiAn Analysis of COVID-19 Mortality Underreporting BFernando BorgesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Does Contact Tracing Work? Quasi-Experimental Evidence From An Excel Error in EnglandDocument61 paginiDoes Contact Tracing Work? Quasi-Experimental Evidence From An Excel Error in EnglandSantiago MarcosÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Survey On Some of The Global Effects of The COVIDocument21 paginiA Survey On Some of The Global Effects of The COVITeddy KatayamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Effect of Stay-at-Home Orders On COVID-19 Infections in The United StatesDocument14 paginiThe Effect of Stay-at-Home Orders On COVID-19 Infections in The United StatesGarcia Family VlogÎncă nu există evaluări

- Influencing Factors of COVID-19 Spreading: A Case Study of ThailandDocument7 paginiInfluencing Factors of COVID-19 Spreading: A Case Study of ThailandPatel SrpÎncă nu există evaluări

- Answer of The Exam - Analytical Technique For Decision MakingDocument10 paginiAnswer of The Exam - Analytical Technique For Decision Makingdinar aimcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippine Death Statistics1Document4 paginiPhilippine Death Statistics1Charish Dwayne Bautista PondalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Overview of Covid-19: An India PerspectiveDocument27 paginiOverview of Covid-19: An India PerspectiveSahilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Health Policy FinalDocument8 paginiHealth Policy FinalAbass DavidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning Outcome: During Finishing This Task Went Over Different Strategies For ExaminingDocument14 paginiLearning Outcome: During Finishing This Task Went Over Different Strategies For Examiningjagrati upadhyayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- © 2020 by The Author(s) - Distributed Under A Creative Commons CC BY LicenseDocument37 pagini© 2020 by The Author(s) - Distributed Under A Creative Commons CC BY LicenseMd. Rakibul Hasan RabbiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Liteture Review On Impact of Covid 19 On Employment OpportunitiesDocument9 paginiLiteture Review On Impact of Covid 19 On Employment OpportunitiesShoaib with r100% (1)

- Public Perceptions Towards COVID-19 Contact Tracing AppsDocument36 paginiPublic Perceptions Towards COVID-19 Contact Tracing AppsEve AthanasekouÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effect of COVID19 On Indian EconomyDocument11 paginiEffect of COVID19 On Indian EconomyNandeesha RameshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unintended Consequences of Lockdowns, COVID-19 and The Shadow Pandemic in IndiaDocument17 paginiUnintended Consequences of Lockdowns, COVID-19 and The Shadow Pandemic in IndiaRiya ShahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annotated-Ence370 20final 20projectDocument11 paginiAnnotated-Ence370 20final 20projectapi-608862113Încă nu există evaluări

- 2020 06 08 COVID19 Report 26Document94 pagini2020 06 08 COVID19 Report 26Umair HasanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ijerph 17 02309 PDFDocument12 paginiIjerph 17 02309 PDFHesbon MomanyiÎncă nu există evaluări

- COVID-19 India Data AnalysisDocument23 paginiCOVID-19 India Data AnalysisPragya JhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quantitative Relationship Between Population Mobility and COVID-19 Growth Rate Based On 14 CountriesDocument29 paginiQuantitative Relationship Between Population Mobility and COVID-19 Growth Rate Based On 14 CountriesJason SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- SSRN Id3638373Document39 paginiSSRN Id3638373kamleshÎncă nu există evaluări

- 06-07-2020-1594021302-8-Ijamss-2. Ijamss - Modeling and Forecasting Novel Corona Cases in India Using Truncated Information A Mathematical ApproachDocument12 pagini06-07-2020-1594021302-8-Ijamss-2. Ijamss - Modeling and Forecasting Novel Corona Cases in India Using Truncated Information A Mathematical Approachiaset123Încă nu există evaluări

- (Amateur Research Essay) The COVID-19 Infodemic - The Causes and Impacts of MisperceptionDocument3 pagini(Amateur Research Essay) The COVID-19 Infodemic - The Causes and Impacts of MisperceptionduongnhatminhbrvtÎncă nu există evaluări

- COVID-19-Related Fake News in Social MediaDocument11 paginiCOVID-19-Related Fake News in Social MediaPrithula Prosun PujaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Overview of Covid-19: An India PerspectiveDocument27 paginiOverview of Covid-19: An India PerspectiveSahilÎncă nu există evaluări

- IT ReportDocument26 paginiIT ReportWrite EnglishÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accounting For Global COVID-19 Diffusion Patterns, January - April 2020Document45 paginiAccounting For Global COVID-19 Diffusion Patterns, January - April 2020Ornica BalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Muhammad Afaq Hanif Fa20-Bse-070 RWSDocument15 paginiMuhammad Afaq Hanif Fa20-Bse-070 RWSAhsan NazirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Covid ImpactDocument50 paginiCovid Impactrsabitha ECE-HICET100% (1)

- COVID-19 Tweets Analysis: Smith Analytics Consortium Data Series WorkshopDocument13 paginiCOVID-19 Tweets Analysis: Smith Analytics Consortium Data Series WorkshopYiyang WangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Age Groups That Sustain Resurging COVID-19 M Monod Et Al 17 Sep 2020Document35 paginiAge Groups That Sustain Resurging COVID-19 M Monod Et Al 17 Sep 2020Martin ThomasÎncă nu există evaluări

- English বাং লা हिहंदी मराठी Follow UsDocument13 paginiEnglish বাং লা हिहंदी मराठी Follow UsMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Skip To Main ContentDocument15 paginiSkip To Main ContentMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- MS Word 2016 Basic Authoring and Testing Guide-AED COPDocument23 paginiMS Word 2016 Basic Authoring and Testing Guide-AED COPGraemeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Empty Cities Have Long Been A Post-Apocalyptic Trope - Now, They Are A RealityDocument9 paginiEmpty Cities Have Long Been A Post-Apocalyptic Trope - Now, They Are A RealityMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- NICE Guideline On Long COVID: Log in Register Subscribe ClaimDocument7 paginiNICE Guideline On Long COVID: Log in Register Subscribe ClaimMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- By Continuing To Use This Site You Consent To The Use of Cookies On Your Device As Described in OurDocument13 paginiBy Continuing To Use This Site You Consent To The Use of Cookies On Your Device As Described in OurMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abu DhabiDocument3 paginiAbu DhabiMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 123Document36 pagini123Mohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 567Document47 pagini567Mohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Subscribe: Menu GODocument17 paginiSubscribe: Menu GOMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 234Document25 pagini234Mohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dubai Suspends Live Entertainment in Hotels and RestaurantsDocument8 paginiDubai Suspends Live Entertainment in Hotels and RestaurantsMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Subscribe: Menu GODocument17 paginiSubscribe: Menu GOMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 567Document47 pagini567Mohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- IMF Hands #India Steepest Cut, Sees #GDP Contracting by 4.5% in FY21, at - Ritusingh Writes.#economy #CoronavirusDocument2 paginiIMF Hands #India Steepest Cut, Sees #GDP Contracting by 4.5% in FY21, at - Ritusingh Writes.#economy #CoronavirusMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dubai Suspends Live Entertainment in Hotels and RestaurantsDocument8 paginiDubai Suspends Live Entertainment in Hotels and RestaurantsMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test 1Document1 paginăTest 1Mohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Explained: The Various Drugs Being Used For Treating Covid-19 Symptoms in India NowDocument2 paginiExplained: The Various Drugs Being Used For Treating Covid-19 Symptoms in India NowMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Srinagar: When: Niyaz Ahmad Lone's House in ShopianDocument1 paginăSrinagar: When: Niyaz Ahmad Lone's House in ShopianMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- In The Supreme Court of India: Yousuf Khan & Ors. (A)Document40 paginiIn The Supreme Court of India: Yousuf Khan & Ors. (A)Mohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Related Topics: Share This StoryDocument4 paginiRelated Topics: Share This StoryMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Output Is Projected To Decline by - 4.9% in 2020: International Monetary FundDocument2 paginiGlobal Output Is Projected To Decline by - 4.9% in 2020: International Monetary FundMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Output Is Projected To Decline by - 4.9% in 2020: International Monetary FundDocument2 paginiGlobal Output Is Projected To Decline by - 4.9% in 2020: International Monetary FundMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coronavirus Forces United States, United Kingdom To Cancel Antarctic Field ResearchDocument3 paginiCoronavirus Forces United States, United Kingdom To Cancel Antarctic Field ResearchMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5Document4 pagini5Mohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Tremendous Peaks of An Earlier Age Part 2Document6 paginiThe Tremendous Peaks of An Earlier Age Part 2Mohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Night Described How A Population, Brutalised by The Indian Army, Were Tempted Into Fighting ForDocument2 paginiNight Described How A Population, Brutalised by The Indian Army, Were Tempted Into Fighting ForMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Noted Jurist and Senior BJP Leader Ram Jethmalani Today Termed The Armed Forces Special Powers ActDocument2 paginiNoted Jurist and Senior BJP Leader Ram Jethmalani Today Termed The Armed Forces Special Powers ActMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Of The Parties Part 3Document3 paginiOf The Parties Part 3Mohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- SevenDocument1 paginăSevenMohammad Khurram QureshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Table 1 Minimum Separation DistancesDocument123 paginiTable 1 Minimum Separation DistancesjhonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ni Elvis ManualDocument98 paginiNi Elvis ManualZhi YiÎncă nu există evaluări

- LighthouseDocument4 paginiLighthousejaneborn5345Încă nu există evaluări

- Thermoplastic Tubing: Catalogue 5210/UKDocument15 paginiThermoplastic Tubing: Catalogue 5210/UKGeo BuzatuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biologically Active Compounds From Hops and Prospects For Their Use - Karabín 2016Document26 paginiBiologically Active Compounds From Hops and Prospects For Their Use - Karabín 2016Micheli Legemann MonteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intro Slow Keyofg: Em7 G5 A7Sus4 G C/G D/F# AmDocument2 paginiIntro Slow Keyofg: Em7 G5 A7Sus4 G C/G D/F# Ammlefev100% (1)

- Apcotide 1000 pc2782Document1 paginăApcotide 1000 pc2782hellmanyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Disectie AnatomieDocument908 paginiDisectie AnatomieMircea SimionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pharmd CurriculumDocument18 paginiPharmd Curriculum5377773Încă nu există evaluări

- All About PlantsDocument14 paginiAll About Plantsapi-234860390Încă nu există evaluări

- Angewandte: ChemieDocument13 paginiAngewandte: ChemiemilicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kuiz1 210114Document12 paginiKuiz1 210114Vincent HoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marvell 88F37xx Product Brief 20160830Document2 paginiMarvell 88F37xx Product Brief 20160830Sassy FiverÎncă nu există evaluări

- Multiple Choice Enzymes Plant and Animal NutritionDocument44 paginiMultiple Choice Enzymes Plant and Animal Nutritionliufanjing07Încă nu există evaluări

- Fret Position Calculator - StewmacDocument1 paginăFret Position Calculator - StewmacJuan Pablo Sepulveda SierraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reactive Dyes For Digital Textile Printing InksDocument4 paginiReactive Dyes For Digital Textile Printing InksDHRUVÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eating With Chloe Lets EatDocument150 paginiEating With Chloe Lets Eatemily.jarrodÎncă nu există evaluări

- ASCE Snow Loads On Solar-Paneled RoofsDocument61 paginiASCE Snow Loads On Solar-Paneled RoofsBen100% (1)

- Conformational Analysis: Carey & Sundberg: Part A Chapter 3Document53 paginiConformational Analysis: Carey & Sundberg: Part A Chapter 3Dr-Dinesh Kumar100% (1)

- Product Stock Exchange Learn BookDocument1 paginăProduct Stock Exchange Learn BookSujit MauryaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hot Topic 02 Good Light Magazine 56smDocument24 paginiHot Topic 02 Good Light Magazine 56smForos IscÎncă nu există evaluări

- Product Recommendation Hyster Forklift Trucks, Electric J1.60XMTDocument1 paginăProduct Recommendation Hyster Forklift Trucks, Electric J1.60XMTNelson ConselhoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Navy Supplement To The DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, 2011Document405 paginiNavy Supplement To The DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, 2011bateljupko100% (1)

- Application of PCA-CNN (Principal Component Analysis - Convolutional Neural Networks) Method On Sentinel-2 Image Classification For Land Cover MappingDocument5 paginiApplication of PCA-CNN (Principal Component Analysis - Convolutional Neural Networks) Method On Sentinel-2 Image Classification For Land Cover MappingIJAERS JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prawn ProcessingDocument21 paginiPrawn ProcessingKrishnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chemical Bonds WorksheetDocument2 paginiChemical Bonds WorksheetJewel Mae MercadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- PEDocument12 paginiPEMae Ann Base RicafortÎncă nu există evaluări

- 9701 w09 QP 21Document12 pagini9701 w09 QP 21Hubbak KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Index PDFDocument159 paginiIndex PDFHüseyin IşlakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Generalized Anxiety DisorderDocument24 paginiGeneralized Anxiety DisorderEula Angelica OcoÎncă nu există evaluări