Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Taisho Democracy in Japan - 1912-1926 - Facing History and Ourselves

Încărcat de

fromatob3404Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Taisho Democracy in Japan - 1912-1926 - Facing History and Ourselves

Încărcat de

fromatob3404Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

1 of 7

Taisho Democracy in Japan: 1912-1926

With the death of Emperor Meiji in 1912 a great deal of

uncertainty about Japan’s future followed. Many

believed that Meiji Japan had flourished under the

steadfast rule of the emperor who reigned for more than

40 years. Now his first son, Yoshihito, ascended to the

throne and took the name Taisho, ushering in the next

era. Those deeply loyal to Emperor Meiji and resistant to

modernization efforts were particularly vulnerable.

Some would hold fast to the centuries of Japanese

tradition, rejecting any shifts in gender roles or

education and military reforms, while other reformers

embraced change.

The young Taisho emperor was born in 1879 and at an

early age contracted cerebral meningitis. The ill effects

of the disease, including physical weakness and episodes

of mental instability, plagued him throughout his reign.

Because of his sickness there was a shift in the structure

of political power from the old oligarchic advisors under

Meiji to the members of the Diet of Japan—the elected

representative officials increasingly gaining influence

and power. By 1919 Emperor Taisho’s illness prevented

him from performing any official duties altogether. By

1921 Hirohito, his first son, was named ses-ho, or prince

regent of Japan. From this point forward, Emperor

Taisho no longer appeared in public.

Despite the lack of political stability, modernization

efforts during Taisho continued. A greater openness and

desire for representative democracy took hold. Literary

societies, mass-audience magazines, and new

publications flourished. University cities like Tokyo

2 of 7

witnessed a burgeoning culture of European-style cafés,

with young people donning Western clothing. A thriving

music, film, and theater culture grew, with some calling

this period “Japan’s roaring '20s.”

For these reasons the Taisho era has also been called

Taisho democracy as Japan enjoyed a climate of political

liberalism unforeseen after decades of Meiji

authoritarianism.1 One of the leading political figures,

and the man who coined the term Taisho democracy,

was professor of law and political theory Dr. Yoshino

Sakuzo. After observing and traveling extensively in the

West, he returned to Japan and wrote a series of articles

promoting the development of a liberal and social

democratic tradition in Japan. In the preface to his 1916

essay “On the Meaning of Constitutional Government,”

Yoshino wrote:

[T]he fundamental prerequisite for

perfecting constitutional government,

especially in politically backwards

nations, is the cultivation of knowledge

and virtue among the general population.

This is not the task that can be

accomplished in a day. Think of the

situation in our own country [Japan]. We

instituted constitutional government

before the people were prepared for it. As

a result there have been many failures. . . .

Still, it is impossible to reverse course and

return to the old absolutism, so there is

nothing for us to do but cheerfully take

the road of reform and progress.

Consequently, it is extremely important

not to rely on politicians alone but to use

the cooperative efforts of educators,

religious leaders, and thinkers in all areas

of society.2

3 of 7

With such ideas openly circulating, Japan also saw the

rise of mass movements advocating political change.

Labor unions started large-scale strikes to protest labor

inequities, political injustices, treaty negotiations, and

Japanese involvement in World War I. The number of

strikes rose from 108 in 1914 to 417 strikes in 1918. At the

outset of World War I, there were 49 labor organizations

and 187 at the end, with a membership total of 100,000.3

A movement for women’s suffrage soon followed. While

the right of women to vote was not recognized until

1946, these early feminists were instrumental in

overturning Article 5 of the Police Security Act, which

had prevented women from joining political groups and

actively participating in politics. They also challenged

cultural and family traditions by entering the work-

force in greater numbers and asserting their financial

independence.

One of the most widespread political protests occurred

in 1918 with Japan’s rice riots. Like the rest of the world,

Japan was experiencing wartime inflation and low

wages. The dramatic increase in the price of rice, a staple

of the Japanese diet, had an impact on the entire

country. In August 1918 in the fishing village of Uotsu,

fishermen’s wives attempted to stop the export of grain

from their village in protest against high prices. By

October more than 30 separate riots were documented,

the vast majority organized by women workers. They

refused to load grain, attacked rice merchants, and

protested the continued high prices. They inspired other

protests, such as the demand by coal miners for higher

wages and humane work conditions.

Much of this social unrest, political uprising, and

cultural experimentation came to a halt on September 1,

1923. On this day a powerful earthquake struck Japan

measuring 7.8 on the Richter scale. This natural disaster

is referred to today as the Great Kanto Earthquake. The

force of the quake was so strong that a 93-ton Buddha

4 of 7

statue 37 miles from the epicenter moved almost two

feet. The disaster devastated the entire city of Tokyo, the

third largest city in the world at that time, destroyed the

port city of Yokohama, and caused large-scale

destruction in the surrounding area. The earthquake

and subsequent fires killed more than 150,000 people

and left over 600,000 homeless. Martial law was

immediately instituted, but it couldn’t prevent mob

violence and the targeting of ethnic minorities. Koreans

living in Tokyo were targeted, as rumors spread that

they were poisoning the water and sabotaging

businesses. Newspapers reported these rumors as fact.

According to standard accounts over 2,600 Koreans and

160–170 Chinese were killed, with about 24,000 detained

by police. The numbers include political opponents such

as the anarchist Osugi Sakai, his wife, and their six-year-

old nephew, who were tortured to death in military

police custody. The officer responsible for this crime

later became a high-ranking official in Manchuria.4

Using the social unrest as an excuse, the Japanese

Imperial Army moved in to detain and arrest political

activists they believed were radicals. After events

surrounding the earthquake, the relationship between

the military and the emperor began to shift. According

to the Meiji Constitution, the emperor led the army and

navy. However, all military decisions were actually made

by the prime minister or high-level cabinet ministers. As

political activists became more vocal, many were

abducted and were never seen again. Local police and

army officials who were responsible claimed these so-

called radicals used the earthquake crisis as an excuse to

overthrow the government. More repression and

violence soon followed. Prime Minister Hara (1918–1921)

was assassinated, and a Japanese anarchist attempted to

assassinate Taisho’s first son, Hirohito.

Order was firmly restored when a more conservative

arm of the government gained influence and passed the

5 of 7

Peace Preservation Law of 1925. Besides threatening up

to 10 years imprisonment for anyone attempting to alter

the kokutai (rule by the emperor and imperial

government, as opposed to popular sovereignty), this

law severely curtailed individual freedom in Japan and

attempted to eliminate any public dissent.5The

transition in the emperor’s role to one of greater power

began with the death of Emperor Taisho on December

18, 1926. Following tradition, his son Hirohito ascended to

the throne and chose the name Showa, mean- ing “peace

and enlightenment.” Hirohito neither suffered from

physical or mental ailments like his father nor held the

commanding presence of his grandfather. Rather,

Hirohito began his reign by per- forming all the

ceremonial duties flawlessly but appearing in public

only for highly orchestrated formal state occasions. Over

time as the political climate within Japan shifted to a

more militaristic stance, so did the role of the emperor.

One specific gesture is emblematic of the changes

occurring in the role and power of the emperor. When

Hirohito first appeared in public in the early years of his

reign, commoners would always remain dutifully seated

to avoid appearing above the emperor, but they were

permitted to look at him. By 1936 it was illegal for any

ordinary Japanese citizen to even look at the emperor.

Citations

1 : Professor Kevin M. Doak also argues that it is

important to recognize that “nationalism, especially

the popular ethnic version, were the central

ingredient in what has come to be known as Taisho

democracy.” Doak, “Culture, Ethnicity, and the State

in Early Twentieth-Century Japan,” 19.

2 : Wm. Theodore de Bary, Carol Gluck, and Arthur

E. Tiedemann, eds., Sources of Japanese Tradition,

2nd edition, vol. 2, (New York: Columbia University

Press, 2005), 838.

6 of 7

3 : In 1914 over 5,700 workers were involved in

strikes and by 1918 over 66,000 were involved.

4 : Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi (professor, York

University), private correspondence with the

author, January 22, 2014.

5 : Ironically, this conservative faction passed the

1925 Universal Manhood suffrage Act, increasing

the number of males eligible to vote from 3.3 million

to 12.5 million. It also transformed the most

devastated areas of earthquake-ravaged cities by

building parks and erecting modern concrete

buildings that would withstand future quakes with

funds that came from cutting military spending in

half. Nevertheless, the early stages of repression

and militarism during the final years of the Taisho

era foreshadowed the extreme rise in nationalism

and militarism that followed in the coming decades.

Connection Questions

1. By the Taisho period, Japan had already officially

become a constitutional monarchy. What

observations did Yoshino Sakuzo make about the

transition to democracy in Japan? What does he

suggest is necessary for real change to take root?

2. What changes did reformers in the Taisho era bring

about? What were the greatest challenges

reformers faced as they attempted to bring about

democratic change?

3. Considering what you have learned so far, why do

you think some people felt a need for more

authoritarian rule after the Taisho period? What

gains had Japan made earlier in the century? What

happened during emperor Taisho’s rule?

7 of 7

Related Content

https://www.facinghistory.org/nanjing-atrocities/nation-

building/taisho-democracy-japan-1912-1926

Copyright © 2020 Facing History and Ourselves. We are a

registered 501 (c)(3) charity. Privacy Policy

Our headquarters are located at:

16 Hurd Road, Brookline, MA 02445

Accessibility Feedback

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Estrangement As A Lifestyle-Shklovsky and BrodskyDocument21 paginiEstrangement As A Lifestyle-Shklovsky and Brodskyfromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- Blunders and How To Avoid Them Dunnington PDFDocument147 paginiBlunders and How To Avoid Them Dunnington PDFrajveer404100% (2)

- Failure of The Weimar Republic and Rise of The Nazis HistoriographyDocument2 paginiFailure of The Weimar Republic and Rise of The Nazis HistoriographyNeddimoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moma Matissecutouts PreviewDocument25 paginiMoma Matissecutouts Previewfromatob3404100% (2)

- Stalin - An Overview (Policies and Reforms)Document5 paginiStalin - An Overview (Policies and Reforms)itzkani100% (2)

- Problem ManagementDocument33 paginiProblem Managementdhirajsatyam98982285Încă nu există evaluări

- Why Did The League of Nations FailDocument39 paginiWhy Did The League of Nations FailTroy KalishÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accepting Authoritarianism: State-Society Relations in China's Reform EraDe la EverandAccepting Authoritarianism: State-Society Relations in China's Reform EraEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (2)

- Stalin NotesDocument6 paginiStalin NotesJames PhamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Postwar Japanese NationalismDocument9 paginiPostwar Japanese NationalismAhmad Okta PerdanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of Hirohito's SpeechDocument7 paginiAnalysis of Hirohito's SpeechMuhammad Rizky RÎncă nu există evaluări

- Political Modernization of Meiji JapanDocument18 paginiPolitical Modernization of Meiji JapanRamita UdayashankarÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Rise and Decline of The Soviet EconomyDocument23 paginiThe Rise and Decline of The Soviet EconomyGalers V HarjbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Imperial RussiaDocument21 paginiImperial RussiaOliKnight100% (1)

- The Rise of The Militarists in JapanDocument3 paginiThe Rise of The Militarists in JapanSusi MeierÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paper 1 BibleDocument2 paginiPaper 1 Bibleapi-283532135Încă nu există evaluări

- (Dan Stone) The Historiography of The HolocaustDocument586 pagini(Dan Stone) The Historiography of The HolocaustPop Catalin100% (1)

- Chronological Table of Japanese HistoryDocument4 paginiChronological Table of Japanese HistorySarah SslÎncă nu există evaluări

- Britain During The Interwar YearsDocument2 paginiBritain During The Interwar YearsAdrian IlinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Russian RevolutionDocument8 paginiRussian Revolutionapi-153583590Încă nu există evaluări

- Interpretations of Nazi GermanyDocument5 paginiInterpretations of Nazi GermanyWill Teece100% (1)

- Theater 10 Syllabus Printed PDFDocument7 paginiTheater 10 Syllabus Printed PDFJim QuentinÎncă nu există evaluări

- 新日本建設に関する詔書 (Humanity Declaration - Hirohito)Document5 pagini新日本建設に関する詔書 (Humanity Declaration - Hirohito)David YompianÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Successful Were Stalin's Economic PoliciesDocument2 paginiHow Successful Were Stalin's Economic PoliciesGuille Paz100% (1)

- Charter Oath 1868Document2 paginiCharter Oath 1868scribed32198Încă nu există evaluări

- Cold War 8Document217 paginiCold War 8api-248720797Încă nu există evaluări

- The Charter Oath As Officially PublishedDocument3 paginiThe Charter Oath As Officially PublishedThiago PiresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ib History Paper 1 TipsDocument3 paginiIb History Paper 1 TipsAli AreiqatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Move To Global War JapanDocument35 paginiMove To Global War JapanSaketh Vuppalapati100% (2)

- MCN Drill AnswersDocument12 paginiMCN Drill AnswersHerne Balberde100% (1)

- The Role of The Military in Turkish Poli PDFDocument20 paginiThe Role of The Military in Turkish Poli PDFusman93pk100% (1)

- Turkey and the West: From Neutrality to CommitmentDe la EverandTurkey and the West: From Neutrality to CommitmentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Japanese Term 2 Final NotesDocument67 paginiJapanese Term 2 Final NotesLu CasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Notes On Rise of StalinDocument2 paginiNotes On Rise of StalinChong Jun WeiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Meiji Constitution PDFDocument5 paginiMeiji Constitution PDFsmrithiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Cold War Era PDFDocument3 paginiThe Cold War Era PDFNarayanan Mukkirikkad Sreedharan96% (23)

- Revision Notes Cold War 1945-1963Document6 paginiRevision Notes Cold War 1945-1963shahrilmohdshahÎncă nu există evaluări

- To What Extent Was Khrushchev Successful in His Political and Economic ReformsDocument2 paginiTo What Extent Was Khrushchev Successful in His Political and Economic ReformsAnonymous GQXLOjndTbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Democracy in Japan - From Meiji To MacArthurDocument10 paginiDemocracy in Japan - From Meiji To MacArthurHua Hidari YangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 1 - Beginnings of Cold War - Yalta & PotsdamDocument6 paginiLesson 1 - Beginnings of Cold War - Yalta & Potsdamapi-19773192100% (1)

- Lanterna IB Revision Skills Guide IB HistoryDocument9 paginiLanterna IB Revision Skills Guide IB HistorynoorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stalin's Rise and RuleDocument5 paginiStalin's Rise and RuleBel AngeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural RevolutionDocument28 paginiCultural RevolutionPRPRPR_XP9_Încă nu există evaluări

- The Nature of Tsarism and The Policies of Nicholas IIDocument3 paginiThe Nature of Tsarism and The Policies of Nicholas IITom Meaney100% (2)

- Rmany 2018 3 1933 1938Document48 paginiRmany 2018 3 1933 1938MarcellÎncă nu există evaluări

- Causes of The Cold War SummaryDocument4 paginiCauses of The Cold War SummaryKhairul SincereÎncă nu există evaluări

- Move To Global War EuropeDocument37 paginiMove To Global War EuropeSaketh VuppalapatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Did Stalin Emerge As Leader of The Soviet Union Between 1924 and 1929Document5 paginiWhy Did Stalin Emerge As Leader of The Soviet Union Between 1924 and 1929aurora6119Încă nu există evaluări

- Japan - On The Move To Global WarDocument13 paginiJapan - On The Move To Global WarNataliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hitler Rise To PowerDocument6 paginiHitler Rise To PowerpianorificationÎncă nu există evaluări

- World War 1 and Roaring 20sDocument22 paginiWorld War 1 and Roaring 20sapi-355176482100% (1)

- A Level AQA HIS2LThe Impact of Stalins LeadershipDocument108 paginiA Level AQA HIS2LThe Impact of Stalins Leadershipannabelle gonzalezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stalinism As Totalitarianism EssayDocument2 paginiStalinism As Totalitarianism EssayJames Pham50% (2)

- IB History Results of WW1 SummaryDocument8 paginiIB History Results of WW1 SummaryRoy KimÎncă nu există evaluări

- CH 30 Sec 3Document5 paginiCH 30 Sec 3api-263257778100% (1)

- 222alevel Euro NotesDocument134 pagini222alevel Euro Notesi krisel263Încă nu există evaluări

- Why Did The Provisional Government FailDocument2 paginiWhy Did The Provisional Government Failsanjayb1008491Încă nu există evaluări

- League of Nations O LevelDocument11 paginiLeague of Nations O LevelShark100% (2)

- External and Internal Factors For Rise of FascismDocument79 paginiExternal and Internal Factors For Rise of FascismAdeline Chen100% (3)

- IB History Released QuestionsDocument15 paginiIB History Released Questionsapester101Încă nu există evaluări

- Japanese Foreign Policy OldDocument27 paginiJapanese Foreign Policy OldNevreda ArbianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essay Question CollectivisationDocument2 paginiEssay Question CollectivisationKatie MillsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paper 1: Move To Global War Japanese Expansion in East AsiaDocument48 paginiPaper 1: Move To Global War Japanese Expansion in East AsiaEnriqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introducing The TOK Essay - Writing An Essay PlanDocument3 paginiIntroducing The TOK Essay - Writing An Essay PlanAziz KarimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paris Peace Conference: The Big ThreeDocument23 paginiParis Peace Conference: The Big ThreeTeo Jia Ming Nickolas100% (5)

- English nationalism, Brexit and the Anglosphere: Wider still and widerDe la EverandEnglish nationalism, Brexit and the Anglosphere: Wider still and widerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Troubled Apologies Among Japan, Korea, and the United StatesDe la EverandTroubled Apologies Among Japan, Korea, and the United StatesÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Margaret Walker Alexander Series in African American Studies) Tracie Church Guzzio - All Stories Are True_ History, Myth, and Trauma in the Work of John Edgar Wideman (Margaret Walker Alexander SerieDocument331 pagini(Margaret Walker Alexander Series in African American Studies) Tracie Church Guzzio - All Stories Are True_ History, Myth, and Trauma in the Work of John Edgar Wideman (Margaret Walker Alexander Seriefromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- Opinion - Joe Says It Ain't SoDocument8 paginiOpinion - Joe Says It Ain't Sofromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- Biden Denies Tara Reade's Assault Allegation - It Never Happened' - The New York Times-1may2020Document4 paginiBiden Denies Tara Reade's Assault Allegation - It Never Happened' - The New York Times-1may2020fromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- Donald Judd Poster-1971Document1 paginăDonald Judd Poster-1971fromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- Iranian Artist Farghadani, Who Drew Parliament As Animals, Sentenced To 12-Plus Years - The Washington PostDocument2 paginiIranian Artist Farghadani, Who Drew Parliament As Animals, Sentenced To 12-Plus Years - The Washington Postfromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- 2013 03 Social Dilemmas Vervet Monkeys PatienceDocument2 pagini2013 03 Social Dilemmas Vervet Monkeys Patiencefromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- Loftboard Annual Report 2013Document12 paginiLoftboard Annual Report 2013fromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- Nyc Public HousingDocument32 paginiNyc Public Housingfromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- Women in Science Writing: A Step Towards SolutionsDocument51 paginiWomen in Science Writing: A Step Towards Solutionsfromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- Using The Google N-Gram Corpus To Measure Cultural ComplexityDocument8 paginiUsing The Google N-Gram Corpus To Measure Cultural Complexityfromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- RSN Cotton Pledge Update 20131011 FINALDocument2 paginiRSN Cotton Pledge Update 20131011 FINALfromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- Beebe OpDocument21 paginiBeebe Opfromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- Appendix D - Air QualityDocument4 paginiAppendix D - Air Qualityfromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

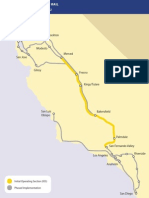

- Sacramento: Initial Operating Section (IOS) Phased ImplementationDocument1 paginăSacramento: Initial Operating Section (IOS) Phased Implementationfromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- The Gun Owner Next Door What You Don T Know About The WeaponsDocument4 paginiThe Gun Owner Next Door What You Don T Know About The Weaponsfromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- Appendix F - Detailed Noise Monitoring ResultsDocument4 paginiAppendix F - Detailed Noise Monitoring Resultsfromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- Surveying-Table of ContentsDocument1 paginăSurveying-Table of Contentsfromatob3404Încă nu există evaluări

- Barangay Sindalan v. CA G.R. No. 150640, March 22, 2007Document17 paginiBarangay Sindalan v. CA G.R. No. 150640, March 22, 2007FD BalitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Win Tensor-UserGuide Optimization FunctionsDocument11 paginiWin Tensor-UserGuide Optimization FunctionsadetriyunitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Star QuizDocument3 paginiStar Quizapi-254428474Încă nu există evaluări

- Department of Chemistry Ramakrishna Mission V. C. College, RaharaDocument16 paginiDepartment of Chemistry Ramakrishna Mission V. C. College, RaharaSubhro ChatterjeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Challenges For Omnichannel StoreDocument5 paginiChallenges For Omnichannel StoreAnjali SrivastvaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philosophy of Jnanadeva - As Gleaned From The Amrtanubhava (B.P. Bahirat - 296 PgsDocument296 paginiPhilosophy of Jnanadeva - As Gleaned From The Amrtanubhava (B.P. Bahirat - 296 PgsJoão Rocha de LimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hawthorne Studies RevisitedDocument25 paginiThe Hawthorne Studies Revisitedsuhana satijaÎncă nu există evaluări

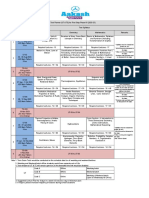

- UT & TE Planner - AY 2023-24 - Phase-01Document1 paginăUT & TE Planner - AY 2023-24 - Phase-01Atharv KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinincal Decision Support SystemDocument10 paginiClinincal Decision Support Systemم. سهير عبد داؤد عسىÎncă nu există evaluări

- Best-First SearchDocument2 paginiBest-First Searchgabby209Încă nu există evaluări

- Musculoskeletan Problems in Soccer PlayersDocument5 paginiMusculoskeletan Problems in Soccer PlayersAlexandru ChivaranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Describing LearnersDocument29 paginiDescribing LearnersSongül Kafa67% (3)

- SUBSET-026-7 v230 - 060224Document62 paginiSUBSET-026-7 v230 - 060224David WoodhouseÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Study of Consumer Behavior in Real Estate Sector: Inderpreet SinghDocument17 paginiA Study of Consumer Behavior in Real Estate Sector: Inderpreet SinghMahesh KhadeÎncă nu există evaluări

- City/ The Countryside: VocabularyDocument2 paginiCity/ The Countryside: VocabularyHương Phạm QuỳnhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Karly Hanson RèsumèDocument1 paginăKarly Hanson RèsumèhansonkarlyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Preparedness of The Data Center College of The Philippines To The Flexible Learning Amidst Covid-19 PandemicDocument16 paginiThe Preparedness of The Data Center College of The Philippines To The Flexible Learning Amidst Covid-19 PandemicInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis FulltextDocument281 paginiThesis FulltextEvgenia MakantasiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2023-Tutorial 02Document6 pagini2023-Tutorial 02chyhyhyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Insung Jung An Colin Latchem - Quality Assurance and Acreditatión in Distance Education and e - LearningDocument81 paginiInsung Jung An Colin Latchem - Quality Assurance and Acreditatión in Distance Education and e - LearningJack000123Încă nu există evaluări

- Java ReviewDocument68 paginiJava ReviewMyco BelvestreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gandhi Was A British Agent and Brought From SA by British To Sabotage IndiaDocument6 paginiGandhi Was A British Agent and Brought From SA by British To Sabotage Indiakushalmehra100% (2)

- 206f8JD-Tech MahindraDocument9 pagini206f8JD-Tech MahindraHarshit AggarwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Article 1156 Gives The Civil Code Definition of Obligation, in Its Passive Aspect. Our Law MerelyDocument11 paginiArticle 1156 Gives The Civil Code Definition of Obligation, in Its Passive Aspect. Our Law MerelyFeir, Alexa Mae C.Încă nu există evaluări

- Exercise No.2Document4 paginiExercise No.2Jeane Mae BooÎncă nu există evaluări