Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Gillespie2010 PDF

Încărcat de

Ángela María GuevaraTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Gillespie2010 PDF

Încărcat de

Ángela María GuevaraDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Rehabilitation NURSING

Free CE OFFERING

FOR ARN Members

Workplace Violence in

Healthcare Settings: Risk

Factors and Protective Log on to www.

Strategies rehabnurse.org and visit

the Education page for

Gordon Lee Gillespie, PhD RN PHCNS-BC • Donna M. Gates, EdD RN FAAN • Margaret more details

Miller, EdD CNS RN • Patricia Kunz Howard, PhD RN CEN FAEN

KEY WORDS

This article describes the risk factors and protective strategies associated with workplace violence perpetrated by patients health care

and visitors against healthcare workers. Perpetrator risk factors for patients and visitors in healthcare settings include workplace violence

mental health disorders, drug or alcohol use, inability to deal with situational crises, possession of weapons, and being

a victim of violence. Worker risk factors are gender, age, years of experience, hours worked, marital status, and previous

workplace violence training. Setting and environmental risk factors for experiencing workplace violence include time of

day and presence of security cameras. Protective strategies for combating the negative consequences of workplace violence

include carrying a telephone, practicing self-defense, instructing perpetrators to stop being violent, self- and social support,

and limiting interactions with potential or known perpetrators of violence. Workplace violence is a serious and growing

problem that affects all healthcare professionals. Strategies are needed to prevent workplace violence and manage the nega-

tive consequences experienced by healthcare workers following violent events.

Workplace violence is a problem plaguing all money, transporting or delivering passengers or

employers and employees who work in healthcare items, working with people who are more likely

settings. Physical violence can result in physical to be violent, working in the community setting

injuries or, in extreme cases, death of a worker or high crime areas, working during nighttime

(Bergen, Chen, Warner, & Fingerhut, 2008; Hart- or early morning hours, guarding valuables, and

ley, Biddle, & Jenkins, 2005). Verbal violence is working alone. Perpetrator, worker, and setting and

another form of workplace aggression and has been environmental risk factors are described below.

linked to negative consequences, including anxiety,

Perpetrator Risk Factors

depression, and stress (Spector, Coulter, Stockwell,

Mental health disorders (such as dementia, schizo-

& Matz, 2007). Violence affects workers from all

phrenia, anxiety, acute stress reaction, suicidal ide-

disciplines in the healthcare field. DuHart (2001)

ation, and alcohol and drug intoxication [American

reported that both physicians and nurses were

Medical Association, 2007]) have often been identi-

victims of workplace violence—the rate of physical

fied in people who have committed workplace

violence committed against physicians was 16.2 per

violence (Catlette, 2005; Gates, Fitzwater, & Succop,

1,000 workers and against nurses it was 21.9 per

2003; Gates, Ross, & McQueen, 2006; Gillespie,

1,000 workers. Other healthcare workers, including

2008; James, Madeley, & Dove, 2006; Lee, Gerber-

patient care assistants, were assaulted at a rate of

ich, Waller, Anderson, & McGovern, 1999). Patient

8.5 per 1,000 workers (DuHart). The purpose of this

dementia was identified as a factor in 87% of physi-

article is to describe the risk factors and protective

cal assaults on nursing home assistants (Gates et

strategies associated with workplace violence per-

al., 2003). Mandiracioglu and Cam (2006) found

petrated by patients and visitors against healthcare

that patient dementia was linked to 11% of violent

workers.

events while other psychiatric diseases were linked

to another 25%. Gates and colleagues’ study (2003)

Risk Factors for Workplace Violence

may have reported an increased rate of violence

in Healthcare Settings

committed by patients with dementia because a

Healthcare workers are exposed to a variety of fac-

larger percentage of nursing home residents had

tors that increase their risk for physical and verbal

dementia in their particular study sites.

workplace violence from patients and visitors. The

Using the Staff Observation Aggression Scale–

National Institute for Occupational Safety and

Revised, Almvik, Rasmussen, and Woods (2006)

Health (NIOSH, 1996) reported several risk fac-

studied male and female patients with Alzheimer’s

tors, including working with the public, handling

Rehabilitation Nursing • Vol. 35, No. 5 • September/October 2010 177

Workplace Violence in Healthcare Settings: Risk Factors and

Protective Strategies

disease and the severity of physical violence they (5.3%, n = 35) and verbal violence (5.7%, n = 122).

committed against their healthcare workers. Alm- James and colleagues (2006) reported similar findings

vik and colleagues determined that the severity of for gender when studying safety event reports from a

physical violence perpetrated by male patients was hospital in the United Kingdom. Males (66%, n = 97)

significantly greater than violence perpetrated by fe- and patients between 16 and 35 years (55%, n = 82)

male patients (p < .01). This may be because men are were most likely to be perpetrators of violence.

more likely to enact physical violence and women The sheer volume of weapons being brought into

are more likely to enact verbal violence. In addition, healthcare settings today may increase the potential

men are physically capable of causing more bodily for violence against healthcare workers. Peek-Asa,

injury when hitting, striking, or pushing healthcare Cubbin, and Hubbell (2002) noted that in 2000, pa-

workers compared with women who commit physi- tients were more likely to carry guns and knives

cal violence. when being treated in a healthcare setting than in

Another leading perpetrator risk factor for ver- 1990. Sixteen years ago, McAneney and Shaw (1994)

bal or physical violence is the influence of drugs or found that more than one-half of pediatric ED direc-

alcohol (Catlette, 2005; Crilly, Chaboyer, & Creedy, tors had already started confiscating weapons from

2004; Chaplin, McGeorge, & Lelliott, 2006; Gates et pediatric patients. DuHart (2001) reported that 11%

al., 2006; Gerberich et al., 2004; Gillespie, 2008; James of perpetrators used a weapon during the commis-

et al., 2006; Keely, 2002; Keough, Schlomer, & Bollen- sion of violent events against healthcare workers.

berg, 2003; Kowalenko, Walters, Khare, & Comptom, Although some EDs instituted a weapon-screening

2005; Lin & Liu, 2005). In one study, 35% of healthcare system in triage, patients who arrived by ambulance

workers believed that the violent perpetrator was us- were not routinely checked for the presence of weap-

ing drugs or alcohol before the violent event (DuHart, ons (McAneney & Shaw).

2001). In a second study, participants believed that Being a victim of violence, particularly when the

perpetrators were under the influence of drugs or violence resulted from a firearm injury, is a perpe-

alcohol in 50% of all verbally violent events and 96% trator factor significantly linked to enacting violence

of all physically violent events (Crilly et al.). against others (Bingenheimer, Brennan, & Earls,

Patients’ and visitors’ inability to deal with a crisis 2005; Cunningham et al., 2009). Bingenheimer and

situation is another perpetrator risk factor for workplace colleagues tracked 1,517 Chicago adolescents longi-

violence (Catlette, 2005; Gates et al., 2006; Gillespie, tudinally and found that adolescents who had seen

2008). For example, the stress experienced during an or been victims of violence were significantly more

emergency department (ED) visit may create a crisis likely than adolescents with no exposure to violence

during which patients or visitors are no longer able to to self-report impulsivity (p < .0001) and aggression

deal with a situation as they normally would (Broer- toward others (p < .0001) and commit violent offenses

ing, Campbell, Favand, Galvin, & Holleran, 2007). This (p < .0001). These behaviors increase the likelihood

stress may increase verbal or physical violence. Crises that the patient who is a victim of violence will be

can occur when there are disagreements with the medi- violent toward the healthcare workers providing his

cal plan, denials of a service or request, conflicts with or her care.

healthcare workers, excessive waiting times for as-

Worker Risk Factors

sessments and interventions, inability to focus beyond

Certain characteristics have been found to increase

oneself, perceptions that a healthcare worker is rude or

the risk of workers being targets of workplace

uncaring, grief over the death of a child, and inability to

violence in the healthcare setting, including the

change a healthcare outcome (Badger & Mullan, 2004;

worker’s gender, age, years of experience, hours

Catlette; Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine,

worked, marital status, and previous workplace

1997; Ergün & Karadakovan, 2005; Gates et al., 2006;

violence training.

Gillespie; James et al., 2006; Keely, 2002; Lin & Liu, 2005;

Contradictory evidence about whether a worker’s

McAneney & Shaw, 1994).

gender poses a risk for being verbally or physically

Gerberich and colleagues (2004) reported that the

assaulted by patients and visitors exists. Ayranci, Ye-

gender and age of a perpetrator are factors associated

nilmez, Balci, and Kaptanoglu (2006) ascertained that

with violence against healthcare workers. They found

women experienced a higher percentage of verbal

that the majority of verbally violent perpetrators were

and physical violence compared with men, although

men (73%, n = 1,594) age 35–65 (54%, n = 1,186). Phys-

the difference was not significant. However, most

ical violence was most often enacted by men (59%,

researchers reported that men experienced work-

n = 386) and people 66 years or older (64%, n = 423).

place violence significantly more often than women

Children 17 years old and younger represented the

(Anderson & Parish, 2003; Camerino, Estryn-Behar,

smallest group of perpetrators of physical violence

178 Rehabilitation Nursing • Vol. 35, No. 5 • September/October 2010

Conway, van Der Heijdend, & Hasselhorn, 2008;

Ferrinho et al., 2003; Hegney, Plank, & Parker, 2003;

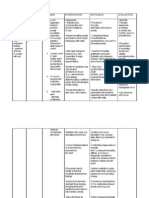

Key Practice Points

Hegney, Eley, Plank, Buikstra, & Parker, 2006; James

1. Being a victim of violence, particularly when the violence

et al., 2006; Miedema, Easley, Fortin, Hamilton, &

resulted from a firearm injury, is significantly linked to

Tatemichi, 2009; Thomas et al., 2006). In contrast,

Tolhurst, Baker, and colleagues (2003) determined

enacting violence against others.

that there was no significant difference in the overall

2. The odds of being physically assaulted at work are reduced

frequency of verbally and physically violent events

when there is a security presence, video cameras present,

between groups of male and female physicians; how-

ever, the percentage of men who experienced at least and organizational policies that address assault prevention

one violent event during the preceding 12 months and repeat violent offenders.

was greater than the percentage of women. Privitera,

Weisman, Cerulli, Tu, and Groman (2005) noted that

3. Social support reduces the negative physical and

the gender of clinical and nonclinical mental health psychological symptoms and negative attitude toward work

workers did not significantly affect the number of following violent events.

verbally or physically violent events they endured.

However, a greater percentage of female physicians

4. The foremost strategy for violence is an effective workplace

had a fear of future violence compared with male violence program focused on preventing violence before it

physicians (Tolhurst, Talbot, et al., 2003). occurs, safely managing violent events, and coping with the

Healthcare workers younger than 40 years old psychological consequences that occur after violent events.

were most frequently the victims of violent events

(Ayranci et al., 2006). Researchers also observed that found no relationship between years of experience

older workers experience significantly less violence and the occurrence of violence; however, their study

than younger workers (Camerino et al., 2008; Hegney was limited to Hispanic nurses working in Texas. It is

et al., 2003, 2006; Lawoko, Soares, & Nolan, 2004; possible that there may be geographical or ethnic dif-

Thomas et al., 2006). In addition, Gates, Fitzwater, ferences between Hispanic Texan nurses and nurses

Telintelo, Succop, and Sommers (2002) researched from other cultures, states, or countries. And although

how a nursing home assistant’s age affected the inci- the accumulated number of violent events spanning

dence of violence. As the age of caregivers increased, a career may increase with each successive year, the

the frequency of violence committed against them incidence per each successive year may decrease. This

decreased. Gates and colleagues posited that this rela- would explain why nurses with less work experience

tionship may be a result of older nursing home assis- report a greater number of violent events per year

tants being more adaptable, patient, and empathetic but more experienced nurses accrue a greater life-

and moving more slowly during interactions with the time number of violent events. In contrast to Ergün

elderly. As with gender, not all research findings for and Karadakovan, Kowalenko and colleagues (2005)

age were consistent. In contrast, Ergün and Karada- determined that less experienced physicians incurred

kovan (2005) provided evidence that nurses report- violence more often than more experienced physi-

ing physical violence were significantly older than cians. The difference in findings may be attributed

nurses who denied an event of physical violence. An- to differences in data analysis; for example, Ergün

derson and Parish (2003) did not detect a relationship and Karadakovan studied cumulative incidence of

between age and the occurrence of violence among violence compared with Kowalenko and colleagues

Hispanic nurses, but this may be due to them study- who studied violent incidences during a 12-month

ing lifetime incidence for workplace violence versus period.

a limited 12-month period for workplace violence. Other healthcare worker characteristics associ-

The lifetime incidence of violence will generally be ated with an increased risk of workplace violence

greater for older workers as compared with younger include the number of hours worked per week

workers because the accumulative number of violent and marital status. Part-time employees experi-

events will increase as each year passes. In contrast, enced reduced risk of physical assault compared

when studying the number of violent events during with full-time employees (OR = 0.35, p < .001;

a 12-month period, the number of violent events per Thomas et al., 2006), even though part-time em-

person per year will likely be less for older workers. ployees experienced a significant (p < .01) increase

Ergün and Karadakovan’s (2005) research showed in violent events from 2001 to 2004 (Hegney et al.,

a significant and positive accumulative relationship 2006). Lin and Liu’s study (2005) reported that un-

between the number of violent events and years of married workers were significantly (p < .01) more

nursing experience. Anderson and Parish (2003) likely to experience workplace violence compared

Rehabilitation Nursing • Vol. 35, No. 5 • September/October 2010 179

Workplace Violence in Healthcare Settings: Risk Factors and

Protective Strategies

with married workers, which may be the result of violence-prevention training has also been associated

married workers being accustomed to working with with increased risks for workplace violence. It is not

others toward a mutual understanding or agreement. known whether employers identified violent work

Evidence about whether violence-prevention train- environments after implementing violence training

ing reduces the risk of workplace violence is contradic- programs or whether the programs were implement-

tory. One group of researchers found that participants ed as a result of workplace violence events. Evidence

who had not attended violence-prevention training has consistently shown, however, that all workers are

were at greater risk for workplace violence than work- at risk for some degree of workplace violence despite

ers who did attend training (Ergün & Karadakovan, their gender, age, years of work experience, and avail-

2005). However, Nachreiner and colleagues (2005) re- ability of training opportunities.

ported that violence training increased the likelihood

Setting and Environmental Risk Factors

of being a victim of physical violence. Specific training

Environmental factors that have been shown to

components that contributed to an increase in the risk

reduce the risk of physical assault against healthcare

for experiencing violence included managing assault-

professionals include controlled access to patient

ive or violent patients (OR = 1.551; p = .03), reporting

areas, reduced wait times, security presence, and

work-related physical assault (OR = 1.639, p > 0.05),

escorting workers to their vehicles (Catlette, 2005;

practicing self-defense (OR = 1.393, p > .05), and rec-

Crilly et al., 2004; Gates et al., 2006; Gerberich et al.,

ognizing risk factors for violence (OR = 1.314, p > .05).

2005; Gillespie, 2008; Lee et al., 1999; Nachreiner

Lee and colleagues (1999) stated that the relative risks

et al., 2005). Lee and colleagues and Ayranci and

for physical violence against a nurse increased when

colleagues (2006) provided evidence that the likeli-

the nurse had received assault-prevention training

hood of a nurse being physically assaulted at work

with a previous employer (RR = 2.57), had completed

was reduced when there was a security presence,

training with his or her current employer (RR = 4.64),

video monitors, and organizational policies that

and his or her employer accepted assault as being

addressed assault prevention and repeat violent

part of the job (RR = 8.14). Data from these studies

offenders. In contrast, Gerberich and colleagues

defy logic. The researchers provided four possible

ascertained that nurses’ risks for experiencing

explanations for the contradiction. First, workplace

physical assault were actually increased when

violence-prevention training may only be provided

employers used video monitors, metal detectors,

in settings in which violence is more common (Lee

or panic buttons. Gerberich and colleagues did not

et al.). Second, the training may increase awareness

provide an explanation for this finding, but it may

of the need to report violent events (Lee et al.). Third,

be the result of an increased awareness of violence

victims of violence may be more likely to recall previ-

leading to increased reporting or an increase in

ous training (Lee et al.). Fourth, workers who receive

employer efforts to make environmental changes

violence-prevention training may be more likely to

for improved worker safety in response to violent

intervene during violent events, whereas their un-

events.

trained counterparts may be more likely to remain

Other researchers have identified that violence is

passive (Nachreiner et al.).

more likely to occur during certain times of the day.

Identifying the healthcare worker most at risk

Ergün and Karadakovan (2005) found that 70% of

for experiencing violent events based on his or her

violent events took place between 4 pm and 8 am,

characteristics is difficult because research findings

which was supported by other researchers (AbuAl-

in the literature are inconsistent. Many researchers

Rub, Khalifa, & Habbib, 2007; Crilly et al., 2004;

have concluded that men are more likely to be vic-

Gates et al., 2006; Gillespie, 2008). Increased rates of

tims of workplace violence (Anderson & Parish, 2003;

violence during evening and nighttime hours may

Camerino, Estryn-Behar, Conway, van Der Heijdend,

be attributed to the types and conditions of patients

& Hasselhorn, 2008; Ferrinho et al., 2003; Hegney,

who seek treatment during later hours, such as in-

Plank, & Parker, 2003; Hegney, Eley, Plank, Buikstra,

toxication and injuries due to violence (McAneney

& Parker, 2006; James et al., 2006; Miedema, Easley,

& Shaw, 1994). Almvik and colleagues (2006) further

Fortin, Hamilton, & Tatemichi, 2009; Thomas et al.,

stated that violent events in long-term care were most

2006); however, it is possible that women are more

likely to occur during daytime and evening hours

frequently the targets of violence, but men become

with few events occurring during nighttime hours.

victims of workplace violence because they intervene.

This difference may be due to the setting; long-term

Older, more experienced workers report a greater

care patients who are aggressive may be asleep dur-

number of violent events throughout their work life,

ing nighttime hours and, therefore, unable to enact

but younger, less experienced workers report a great-

violence against others.

er number of recent violent events. Availability of

180 Rehabilitation Nursing • Vol. 35, No. 5 • September/October 2010

Protective Strategies for Workplace (2005) interviewed eight trauma nurses about their

Violence experiences with workplace violence. Nurses dis-

When violent events occur, some healthcare pro- cussed using self-support techniques such as humor,

fessionals are likely to experience negative conse- talking about the experience, and taking advantage

quences, which can be minimized by protective of leisure time, but did not report whether the partici-

strategies. The literature identified personal pro- pants believed that the interventions were effective

tection as an effective protective strategy against (Catlette). During qualitative interviews of pediatric

violence. In a sample of 116 Iraqi hospital nurses emergency workers, Gillespie discovered that drink-

who reported physical violence, 27% (n = 13) took ing a cold beverage and taking a short break helped

no action and 49% (n = 24) attempted to defend decrease stress following a violent event.

themselves during the event (AbuAlRub et al., Researchers identified that support from other

2007). Self-defense may be an effective strategy to people after a violent event was another strategy for

prevent injury until help arrives or escape from protecting against negative effects. Schat and Kello-

the patient room is possible. Gerberich and col- way (2003) found that support (e.g., showing con-

leagues (2005) determined that hospital nurses cern, listening to the victim’s story) from coworkers

who carried some form of personal protection or a and managers had a positive effect on study partici-

personal cellular telephone had a greatly reduced pants from a Canadian healthcare system who were

odds ratio for being assault compared to those who primarily nurses, patient care assistants, laboratory

did not (.30 to 1); however, when nurses used an and technical assistants, counselors, and social work-

employer’s cellular telephone or personal alarm ers. The support reduced their negative physical and

system, the odds ratio for assault did not decrease psychological symptoms and negative attitudes to-

(1.03 to 1). This discrepancy may reflect employees’ ward their work. Gillespie (2008) concluded that an

lack of knowledge about how to use the employer’s informal debriefing should occur during the same

equipment at the time of the event. Employees who shift as the violent event to prevent future intrusive

carried some form of personal protection may have thoughts from affecting the worker’s sleep.

decreased their risk of a violent event because they Although Schat and Kelloway (2003) identified

were more aware of the potential for violence and social support as an effective strategy for protecting

relied on themselves for protection, and those who against the negative consequences of violent events,

used employers’ measures relied on the employer they also found that the support had no effect on a

for protection. Tolhurst, Talbot, and colleagues worker’s fear of future workplace violence. The re-

(2003) found that 15% (n = 47) of rural physicians searchers concluded that to increase the social sup-

started carrying a cellular telephone with them to port of a worker, this fear must be addressed through

use in the event of workplace violence. Kowalenko interventions such as formal debriefings or profes-

and colleagues (2005) reported that 16% (n = 27) sional counseling sessions.

of Michigan physicians in their study carried a Another protective strategy identified in the litera-

concealed weapon as a form of protection because ture included changing current practices to promote

they feared workplace violence or had previously personal safety. Magin, Adams, Ireland, Heaney, and

experienced a violent event. Darab (2005) found that general practitioner physi-

Healthcare workers also exhibited a no-tolerance cians who worked in urban settings documented their

policy as a strategy for reducing risk for violent destinations after hours, checked in with spouses at

events. Findorff, McGovern, Wall, and Gerberich predetermined periods, and stopped making house

(2005) randomly sampled 4,166 hospital employees calls to patients with whom they were unfamiliar

and found that some instructed perpetrators to stop or who lived in areas of low socioeconomic status.

being verbally violent. These workers were more Female physicians in the study were more likely to

than three times as likely to report the violence com- take their spouses with them during home visits. Tol-

pared to workers who did not tell the perpetrator to hurst, Talbot, and colleagues (2003) stated that 30%

stop. Even though Findorff and colleagues did not of general practitioners made similar changes to their

report whether the perpetrator stopped the verbal after-hours practices based on the risk of workplace

assault when instructed to by workers, the simple violence. Physicians’ most significant change was

act of setting a limit on unacceptable behavior may instructing patients whom they didn’t know or who

have helped protect the worker against long-term, had a history of perpetrating violence to seek health

violence-related stress. care with a different provider when they requested

After experiencing a violent event, some health- to be seen after hours. In fact, 5% of the physicians

care workers protected themselves against the nega- stopped making home visits altogether.

tive effects with self-support (Gillespie, 2008). Catlette

Rehabilitation Nursing • Vol. 35, No. 5 • September/October 2010 181

Workplace Violence in Healthcare Settings: Risk Factors and

Protective Strategies

Summary specific to rehabilitation settings, such as identifying

Perpetrator, worker, and setting and environmental patients with signs of substance abuse withdrawal and

factors have been associated with risk for workplace intervening early or establishing new physical limi-

violence. Perpetrator factors that increased the risk of tations (e.g., inability to perform normal activities of

violence were gender, age, the possession of weapons, daily living). Developing case studies based on real

mental disorders (including dementia), and the influ- violent events reported by rehabilitation healthcare

ence of drugs or alcohol. Worker factors that were workers would increase the personal relevance of ed-

associated with a decreased risk of violence were age, ucational programs. Case studies allow rehabilitation

years of experience, hours worked, and marital status. workers to discuss why the patient or visitor escalated

However, evidence related to the effect of gender and to verbal or physical violence and what actions could

workplace violence training on the risk of workers yield a more positive outcome.

experiencing an assault was conflicting. Setting and Special strategies can be used for patients who are

environmental factors that were related to increased victims of violence (e.g., patients suffering injuries

risk for workplace violence (though not definitively) from gunshots, stabbings, and gang assaults) includ-

included time of the day (daytime versus evening ing limited visitor access and using a pseudonym for

and nighttime hours) and changes to the environment patients. These two strategies may be necessary to

such as the presence of security systems or cameras. prevent exposure to the same stressor that caused the

Employees in healthcare settings cannot prevent all original violent event. Using a pseudonym to regis-

violent events; however, they can use several strate- ter patients in hospital or rehabilitation settings may

gies to protect themselves against the negative conse- help reduce the likelihood that they will be disturbed

quences of workplace violence. Strategies for workers by people who are capable of provoking violent be-

include carrying concealed weapons or personal cel- havior in these patients. Limiting visitor access to two

lular telephones to defend against the consequences of designated individuals (e.g., spouse, parents) reduces

physical violence, instructing perpetrators to stop their the chance that a room full of anxious and stressed

violent acts, engaging in self-care to cope with a violent visitors will resort to workplace violence.

event, receiving support from colleagues and employ- It is important for healthcare workers to recognize

ers, and limiting the availability of after-hours care or that the reported risks for violence are not all inclusive

care for patients who have a history of violence. and that every patient and visitor should be consid-

ered potentially violent. When initial signs of violence

Implications for Rehabilitation Nursing are identified, interventions should be implemented

Both rehabilitation nurses and organizations must immediately, especially de-escalation techniques.

implement strategies to reduce the risks associated These include actively listening to the patient or visi-

with workplace violence. All verbally and physi- tor, attempting to identify concerns and reasons for

cally abusive threatening and harmful acts should the escalation, honestly answering patient and visitor

be considered violent, despite the intent or cogni- questions, allowing access to visitors who may have a

tive accountability of the perpetrator. Even when calming effect on the patient, and providing comfort

perpetrators are cognitively impaired patients, measures (e.g., warm blankets, beverages, snacks, and

violent acts can be physically debilitating or psy- medications for pain, anxiety, and agitation control).

chologically harmful to healthcare professionals Organizational policies addressing workplace vi-

(Badger & Mullan, 2004; Brock, Gurekas, Gelinas, olence should include plans for how to address find-

& Rollin, 2009; Rose & Cleary, 2007). The strategies ing a weapon on a patient or visitor. For example,

depicted in this section are universal regardless of employees should calmly leave the patient’s room,

the patient’s intent or cognitive accountability for notify security personnel that a weapon has been

committing a violent act. discovered, and make no attempts to remove the

The foremost protective strategy is implementing weapon from the patient. Homecare workers should

an effective workplace violence-deterrant program instruct their patients to remove all firearms from

focused on prevention, safe management, and help- the premises before home visits or keep firearms in

ing victims cope with the psychological consequences. a lock box with the ammunition removed and stored

Violence-prevention training should take place when separately. Care plans should indicate that a firearm

workers are hired and should be supplemented with is on the premises. Healthcare workers should be

annual or semiannual updates. Educational compo- informed about and adhere to the organizational

nents may include a description of factors related to policies and provide input about how to keep the

violent events, such as patients or visitors experiencing policies up to date. Experienced workers can men-

a situational crisis or the influence of drugs or alcohol. tor and guide less experienced colleagues in com-

Additional training components may include training munication and care delivery strategies that may

182 Rehabilitation Nursing • Vol. 35, No. 5 • September/October 2010

calm patients and visitors, diffuse tense situations, About the Authors

and discourage the use or presence of weapons. Gordon Lee Gillespie, PhD RN PHCNS-BC, is an assistant

Limited empirical evidence is available for professor at University of Cincinnati, College of Nursing

in Cincinnati, OH. Please address correspondence to him at

protective strategies that are implemented after a gordon.gillespie@uc.edu.

workplace violent event has already occurred. It is

important for all healthcare professionals to recognize Donna M. Gates, EdD RN FAAN, is a professor at University

of Cincinnati, College of Nursing in Cincinnati, OH.

the signs of stress, in patients as well as themselves.

Those experiencing stress should request or be offered Margaret Miller, EdD CNS RN, is professor emeritus at Uni-

a break from the patient-care environment. A plan for versity of Cincinnati, College of Nursing in Cincinnati, OH.

dealing with workplace violence, the means to call Patricia Kunz Howard, PhD RN CEN FAEN, is operations

for help (e.g., personal alarms, cellular telephones, manager at UK Chandler Hospital Emergency & Trauma Ser-

radios), and knowledge about how to use protective vices in Lexington, KY.

technology (e.g., activating a personal alarm) are also

important. It may not be feasible to limit hours of References

AbuAlRub, R. F., Khalifa, M. F., & Habbib, M. B. (2007).

service (e.g., inpatient rehabilitation units or on-call Workplace violence among Iraqi hospital nurses. Journal of

homecare services) or refuse patients; however, or- Nursing Scholarship, 39(3), 281–288.

Almvik, R., Rasmussen, K., & Woods, P. (2006). Challenging

ganizations should implement plans, including flag- behaviour in the elderly—Monitoring violent incidents.

ging charts and specifically soliciting this information International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21, 368–374.

American Medical Association. (2007). Current Procedural

during shift-change reports and new referral intake Terminology, CPT 2008: Professional Edition. Chicago, IL: Author.

processes, to identify patients who have a history of Anderson, C., & Parish, M. (2003). Report of workplace vio-

violence. Patients who have had a violent encounter lence by Hispanic nurses. Journal of Transcultural Nursing,

14(3), 237–243.

with a particular healthcare professional should be re- Ayranci, U., Yenilmez, C., Balci, Y., & Kaptanoglu, C. (2006).

assigned to someone else when feasible. This may not Identification of violence in Turkish health care settings.

Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21(2), 276–296.

be possible when the caregiver (e.g., registered nurse, Badger, F., & Mullan, B. (2004). Aggressive and violent inci-

physical therapist) is the only provider within a geo- dents: Perceptions of training and support among staff car-

graphic area that includes the patient’s residence. To ing for older people and people with head injury. Journal of

Clinical Nursing, 13, 526–533.

provide additional protection, healthcare professionals Bergen, G., Chen, L. H., Warner, M., & Fingerhut, L. A. (2008).

should communicate their location at regular intervals Injury in the United States: 2007 Chartbook. Hyattsville, MD:

National Center for Health Statistics.

with a unit coordinator or home care office, with a plan Bingenheimer, J. B., Brennan, R. T., & Earls, F. J. (2005). Firearm

to be activated if they fail to do so. Home care workers violence exposure and serious violent behavior. Science, 308,

1323–1326.

may need a chaperone or to conduct home care visits

Brock, G., Gurekas, V., Gelinas, A. F., & Rollin, K. (2009). Use of

in pairs to increase personal safety. a “secure room” and a security guard in the management of

the violent, aggressive or suicidal patient in a rural hospital: A

3-year audit. Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine, 14(1), 16–20.

Conclusion Broering, B., Campbell, M., Favand, L., Galvin, A., & Holleran, R.

A review of the literature revealed a number of (Eds.). (2007). Psychosocial aspects of trauma care. In TNCC

Trauma Nursing Core Course Provider Manual (6th ed., pp.

risks and protective strategies associated with 273–284). Des Plaines, IL: Emergency Nurses Association.

violent events committed by patients and visitors Camerino, D., Estryn-Behar, M., Conway, P. M., van Der

against healthcare workers in the workplace. Work- Heijdend, B. I., & Hasselhorn, H. M. (2008). Work-related

factors and violence among nursing staff in the European

place violence is a serious and growing problem in NEXT study: A longitudinal cohort study. International

today’s healthcare settings and affects all employees. Journal of Nursing Studies, 45, 35–50.

Catlette, M. (2005). A descriptive study of the perceptions of

Although protective strategies were identified to workplace violence and safety strategies of nurses work-

reduce negative consequences of violent events, ing in level I trauma centers. Journal of Emergency Nursing,

it is important that researchers conduct rigorous 31(6), 519–525.

Chaplin, R., McGeorge, M., & Lelliott, P. (2006). The national

studies to determine which factors—and in which audit of violence: In-patient care for adults of working age.

combinations—provide the greatest protection. It is Psychiatric Bulletin, 30, 444–446.

Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine, American

important that employers and employees recognize Academy of Pediatrics. (1997). The use of physical restraint

that the only strategy proven to prevent the negative interventions for children and adolescents in the acute care

setting. Pediatrics, 99, 797–798.

consequences of workplace violence is an effective Crilly, J., Chaboyer, W., & Creedy, D. (2004). Violence towards

violence-prevention program. Healthcare profession- emergency department nurses by patients. Accident and

als have a right to be safe while on duty and should Emergency Nursing, 12, 67–73.

Cunningham, R., Knox, L., Fein, J., Harrison, S., Frisch, K.,

be proactive in collaborating with their employers Walton, M., et al. (2009). Before and after the trauma bay:

to create that safe work environment (Occupational The prevention of violent injury among youth. Annals of

Emergency Medicine, 53(4), 490–500.

Safety and Health Administration, 2004). DuHart, D. T. (2001). Violence in the workplace, 1993–99 (NCJ

Publication No. 190076). Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice

Statistics.

Rehabilitation Nursing • Vol. 35, No. 5 • September/October 2010 183

Workplace Violence in Healthcare Settings: Risk Factors and

Protective Strategies

Ergün, F. S., & Karadakovan, A. (2005). Violence towards nurs- Miedema, B., Easley, J., Fortin, P., Hamilton, R., & Tatemichi, S.

ing staff in emergency departments in one Turkish city. (2009). Disrespect, harassment, and abuse: All in a day’s work

International Nursing Review, 52, 154–160. for family physicians. Canadian Family Physician, 55, 279–285.

Ferrinho, P., Biscaia, A., Fronteira, I., Craveiro, I., Antunes, Nachreiner, N. M., Gerberich, S. G., McGovern, P. M., Church,

A. R., Conceição, C., et al. (2003, November 7). Patterns T. R., Hansen, H. E., Geisser, M. S., et al. (2005). Impact

of perceptions of workplace violence in the Portuguese of training on work-related assault. Research in Nursing &

health care sector. Human Resources for Health, 1, Article 1. Health, 28, 67–78.

Retrieved March 14, 2008, from www.human-resources- National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health. (1996).

health.com/content/1/1/11. Violence in the workplace (DHHS NIOSH Publication No.

Findorff, M. J., McGovern, P. M., Wall, M. M., & Gerberich, S. 96–100). Cincinnati, OH: Author.

G. (2005). Reporting violence to a health care employer: A Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (2004). OSHA

cross-sectional study. AAOHN Journal, 53(9), 399–406. Act of 1970. Retrieved February 15, 2009, from www.

Gates, D., Fitzwater, E., & Succop, P. (2003). Relationships of osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_

stressors, strain, and anger to caregiver assaults. Issues in table=OSHACT&p_id=2743.

Mental Health Nursing, 24, 775–793. Peek-Asa, C., Cubbin, L., & Hubbell, K. (2002). Violent events

Gates, D., Fitzwater, E., Telintelo, S., Succop, P., & Sommers, M. and security program in California emergency departments

S. (2002). Preventing assaults by nursing home residents: before and after the 1993 Hospital Security Act. Journal of

Nursing assistants’ knowledge and confidence–a pilot Emergency Nursing, 28(5), 420–426.

study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, Privitera, M., Weisman, R., Cerulli, C., Tu, X., & Groman, A.

3(6), 366–370. (2005). Violence toward mental health staff and safety in the

Gates, D. M., Ross, C. S., & McQueen, L. (2006). Violence work environment. Occupational Medicine, 55, 480–486.

against emergency department workers. Journal of Emergency Rose, J. L., & Cleary, A. (2007). Care staff perceptions of chal-

Medicine, 31(3), 331–337. lenging behavior and fear of assault. Journal of Intellectual &

Gerberich, S. G., Church, T. R., McGovern, P. M., Hansen, H. E., Developmental Disability, 32(2), 153–161.

Nachreiner, M. S., Geisser, A. D., et al. (2004). An epidemio- Schat, A. C. H., & Kelloway, E. K. (2003). Reducing the adverse

logical study of the magnitude and consequences of work consequences of workplace aggression and violence:

related violence: The Minnesota Nurses’ Study. Occupational & The buffering effects of organizational support. Journal of

Environmental Medicine, 61, 495–503. Occupational Health Psychology, 8(2), 110–122.

Gerberich, S. G., Church, T. R., McGovern, P. M., Hansen, H. Spector, P. E., Coulter, M. L., Stockwell, H. G., & Matz, M. W.

D., Nachreiner, N. M., Geissner, M. S., et al. (2005). Risk (2007). Perceived violence climate: A new construct and

factors for work-related assaults on nurses. Epidemiology, its relationship to workplace physical violence and verbal

16(5), 704–409. aggression, and their potential consequences, Work & Stress,

Gillespie, G. L. (2008). Violence against healthcare workers in a 21(2), 117–130.

pediatric emergency department. Unpublished dissertation, Thomas, N. I., Brown, N. D., Hodges, L. C., Gandy, J., Lawson,

University of Cincinnati. L. Lord, J. E., et al. (2006). Risk profiles for four types of

Hartley, D., Biddle, E. A., & Jenkins, E. L. (2005). Societal cost work-related injury among hospital employees. AAOHN

of workplace homicides in the United States, 1992–2001. Journal, 54(2), 61–68.

American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 47, 518–527. Tolhurst, H., Baker, L., Murray, G., Bell, P., Sutton, A., & Dean,

Hegney, D., Eley, R., Plank, A., Buikstra, E., & Parker, V. (2006). S. (2003). Rural general practitioner experience of work-

Workplace violence in Queensland, Australia: The results of related violence in Australia. Australian Journal of Rural

a comparative study. International Journal of Nursing Practice, Health, 11, 231–236.

12, 220–231. Tolhurst, H., Talbot, J., Baker, L., Bell, P., Murray, G., Sutton,

Hegney, D., Plank, A., & Parker, V. (2003). Workplace violence A., et al. (2003). Rural general practitioner apprehension

in nursing in Queensland, Australia: A self-reported study. about work related violence in Australia. Australian Journal

International Journal of Nursing Practice, 9, 261–268. of Rural Health, 11, 237–241.

James, A., Madeley, R., & Dove, A. (2006). Violence and aggres-

sion in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Earn nursing contact hours

Journal, 23(6), 431–434.

Keely, B. R. (2002). Recognition and prevention of hospital vio-

Rehabilitation Nursing is pleased to offer readers

lence. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 21, 236–241. the opportunity to earn nursing contact hours

Keough, V. A., Schlomer, R. S., & Bollenberg, B. W. (2003). for its continuing education articles by taking a

Serendipitous findings from an Illinois ED nursing educa- posttest through the ARN website.The posttest consists of

tional survey reflect a crisis in emergency nursing. Journal of

questions based on this article, plus several assessment

Emergency Nursing, 29, 17–22.

Kowalenko, T., Walters, B. L., Khare, R. K., & Compton, S. questions (e.g., how long did it take you to read the article

(2005). Workplace violence: A survey of emergency physi- and complete the posttest?). A passing score on

cians in the state of Michigan. Annals of Emergency Medicine, the posttest and completion of the assessment questions

46(2), 142–147. yield one nursing contact hour for each article.

Lawoko, S., Soares, J. J. F., & Nolan, P. (2004). Violence towards

psychiatric staff: A comparison of gender, job and envi- To earn contact hours, go to www.rehabnurse.org

ronmental characteristics in England and Sweden. Work & and select the “Education” page. There you can read

Stress, 18(1), 39–55. the article again, or go directly to the posttest assess-

Lee, S. S., Gerberich, S. G., Waller, L. A., Anderson, A., & ment by selecting “RNJ online CE.” The cost for credit

McGovern, P. (1999). Work-related assault injuries among

nurses. Epidemiology, 10(6), 685–691.

is $10 per article. You will be asked for a credit card or

Lin, Y.-H., & Liu, H.-E. (2005). The impact of workplace vio- online payment service number.

lence on nurses in South Taiwan. International Journal of Contact hours for this activity are available at no

Nursing Studies, 42, 773–778. cost to ARN members September 1, 2010, to October

Magin, P. J., Adams, J., Ireland, M., Heaney, S., & Darab, S.

31, 2010, after which time, regular pricing will apply.

(2005). After hours care: A qualitative study of GPs’ percep-

tions of risk of violence and effect on service provision. Contact hours for this activity will not be available after

Australian Family Physician, 34(1–2), 91–92. October 31, 2012.

Mandiracioglu, A., & Cam, O. (2006). Violence exposure and The Association of Rehabilitation Nurses is accredit-

burn-out among Turkish nursing home staff. Occupational ed as a provider of continuing nursing education by the

Medicine, 56, 501–503.

McAneney, C. M., & Shaw, K. N. (1994). Violence in the pedi- American Nurses Credentialing Center’s Commission

atric emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine, on Accreditation (ANCC-COA).

23(6), 1248–1251.

184 Rehabilitation Nursing • Vol. 35, No. 5 • September/October 2010

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Abuse Against Nurses and Its Impact On Stress andDocument8 paginiAbuse Against Nurses and Its Impact On Stress andSri AtiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workplace Health Saf 2015 Darawad 9 17Document9 paginiWorkplace Health Saf 2015 Darawad 9 17IlaJako StefanaticÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workplace Violence A Systematic ReviewDocument8 paginiWorkplace Violence A Systematic ReviewMimeroseÎncă nu există evaluări

- WSNA Position on Preventing Workplace Violence for NursesDocument4 paginiWSNA Position on Preventing Workplace Violence for NursesangieswensonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workplace Violence Against Healthcare Professionals A Systematic Review Mento - 2020Document8 paginiWorkplace Violence Against Healthcare Professionals A Systematic Review Mento - 2020magicuddin100% (1)

- Workplace Bullying, Job Stress, Intent To Jurnal 1Document23 paginiWorkplace Bullying, Job Stress, Intent To Jurnal 1haslinda100% (1)

- Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Disorders For Nurses in Hospitals, Long-Term Care Facilities, and Home Health Care: A Comprehensive ReviewDocument39 paginiPrevalence of Musculoskeletal Disorders For Nurses in Hospitals, Long-Term Care Facilities, and Home Health Care: A Comprehensive ReviewNur IslamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workplace Violence in NursingDocument10 paginiWorkplace Violence in Nursingapi-620190735Încă nu există evaluări

- Workplace Violence Against Resident Doctors in A Tertiary Care Hospital in DelhiDocument5 paginiWorkplace Violence Against Resident Doctors in A Tertiary Care Hospital in DelhiJohn SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- L V B W: Ateral Iolence and Ullying in The OrkplaceDocument12 paginiL V B W: Ateral Iolence and Ullying in The OrkplaceJames LindonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arnetz 2011Document11 paginiArnetz 2011SIMONE ALVES PACHECO DE CAMPOSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vicarious TraumaDocument23 paginiVicarious TraumaPaola A. HartmannÎncă nu există evaluări

- Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Tunisian Hospital Staff: Prevalence and Risk FactorsDocument5 paginiMusculoskeletal Disorders Among Tunisian Hospital Staff: Prevalence and Risk FactorsMerieme SafaaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Running Head: Safety and Protection For Nurses 1Document13 paginiRunning Head: Safety and Protection For Nurses 1api-239898998Încă nu există evaluări

- Adriaenssens - Determinants and Prevalence of Burnout in Emergency NursesDocument13 paginiAdriaenssens - Determinants and Prevalence of Burnout in Emergency NursesaditeocanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2019-Violence Risk Assessment ToolDocument20 pagini2019-Violence Risk Assessment ToolCiara MansfieldÎncă nu există evaluări

- Barriers To Screening For DVDocument10 paginiBarriers To Screening For DVkenya106Încă nu există evaluări

- Risk Assesment in Health Care: T E S: L CDocument8 paginiRisk Assesment in Health Care: T E S: L CZicMicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Work Place ViolenceDocument7 paginiWork Place Violencelucky prajapatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jamda: Ali Azeez Al-Jumaili Bs Pharm, MS, William R. Doucette PHDDocument19 paginiJamda: Ali Azeez Al-Jumaili Bs Pharm, MS, William R. Doucette PHDIstyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workplace Violence Against Healthcare Workers in Jeddah: Determinants, Perceived Impacts and CausesDocument10 paginiWorkplace Violence Against Healthcare Workers in Jeddah: Determinants, Perceived Impacts and CausesIJAR JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- DOL Intolerancia DolorDocument8 paginiDOL Intolerancia DolorJorge Lucas JimenezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workplace Violence in Healthcare: Understanding The ChallengeDocument4 paginiWorkplace Violence in Healthcare: Understanding The ChallengeFirman Suryadi RahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Violence Against Physicians in Jordan 2021Document14 paginiViolence Against Physicians in Jordan 2021magicuddinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Caring For A Relative With Dementia: Family Caregiver BurdenDocument12 paginiCaring For A Relative With Dementia: Family Caregiver Burdenapi-260178502Încă nu există evaluări

- WV Guidelines enDocument18 paginiWV Guidelines eniccang arsenalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Violence in Nursing - JDocument6 paginiViolence in Nursing - Japi-471207189Încă nu există evaluări

- Adriaen S Sens 2015Document13 paginiAdriaen S Sens 2015PeepsÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10 1016@j Ijnurstu 2014 05 011Document36 pagini10 1016@j Ijnurstu 2014 05 011mohamedtradÎncă nu există evaluări

- APNA Workplace Violence Position PaperDocument69 paginiAPNA Workplace Violence Position Paperbast_michaelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Risk Factors and Prevalence of Burnout Syndrome in The Nursing ProfessionDocument11 paginiRisk Factors and Prevalence of Burnout Syndrome in The Nursing ProfessionAnonymous 60gPAU100% (1)

- Near Miss and Minor Occupational InjuryDocument7 paginiNear Miss and Minor Occupational InjuryYew Kian Chee AndrewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effects of Back Massage On Chemotherapy-Related Fatigue and Anxiety: Supportive Care and Therapeutic Touch in Cancer NursingDocument8 paginiEffects of Back Massage On Chemotherapy-Related Fatigue and Anxiety: Supportive Care and Therapeutic Touch in Cancer NursingFauzul AzhimahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ijerph 18 09361 v2Document11 paginiIjerph 18 09361 v2ZANDRA LAVANYA A/P ISAC DEAVADAS STUDENTÎncă nu există evaluări

- Freyd 2005Document22 paginiFreyd 2005Alex Alves de SouzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Violence Against Health Care Workers in A Conflict Affected CityDocument16 paginiViolence Against Health Care Workers in A Conflict Affected CitymagicuddinÎncă nu există evaluări

- KoreaDocument12 paginiKoreagustavoÎncă nu există evaluări

- BBRC Vol 14 No 04 2021-40Document6 paginiBBRC Vol 14 No 04 2021-40Dr Sharique AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Disorders For NursesDocument39 paginiPrevalence of Musculoskeletal Disorders For NursesMiguel RuizÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Journal of Nursing Studies: ReviewDocument14 paginiInternational Journal of Nursing Studies: ReviewBegoña MartinezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Mental Health Impacts of HealthDocument7 paginiThe Mental Health Impacts of HealthReno ShiapahyyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Title Page Title: Workplace Violence Perpetrated by Clients of Healthcare: A Need For Safety andDocument26 paginiTitle Page Title: Workplace Violence Perpetrated by Clients of Healthcare: A Need For Safety andÁngela María GuevaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal Medical SafetyDocument14 paginiJurnal Medical SafetyMARWAH MARWAHÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workplace Violence Against Health Care Providers in Emergency Departments: An Underrated ProblemDocument7 paginiWorkplace Violence Against Health Care Providers in Emergency Departments: An Underrated ProblemAmer Abdulla SachitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zimmerman et al., 2020Document16 paginiZimmerman et al., 2020Just a GirlÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medical Expenditure Effects From Increasing Behavioral Conformity To Patterns of Health-Related BehaviorDocument19 paginiMedical Expenditure Effects From Increasing Behavioral Conformity To Patterns of Health-Related BehaviorRobledoRosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Berecki Gisolf2015Document9 paginiBerecki Gisolf2015Mladen PazinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Selfcare PDFDocument9 paginiSelfcare PDFEmaa AmooraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evidence Based Nursing Practice For Oncology Nursing2Document4 paginiEvidence Based Nursing Practice For Oncology Nursing2Alaina MalsiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ana WPV Position Statement 2015Document23 paginiAna WPV Position Statement 2015AjazbhatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Medicine - Violence Against Emergency - Alaa Hussein1Document12 paginiMedicine - Violence Against Emergency - Alaa Hussein1TJPRC PublicationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental Health Service Use by Cleanup Workers in The Aftermath ofDocument10 paginiMental Health Service Use by Cleanup Workers in The Aftermath ofJoseh Marcos De França da SilvaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discriminacion y Abuso en Residentes de CirugiaDocument12 paginiDiscriminacion y Abuso en Residentes de CirugiaCésar Alejandro Bello PérezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review Health-Seeking BehaviorDocument11 paginiReview Health-Seeking BehaviorDadanMKÎncă nu există evaluări

- Full Article Workplace Aggressionamong Healthcare Professionalsin NigeriaDocument12 paginiFull Article Workplace Aggressionamong Healthcare Professionalsin NigeriaSucea Marius CristinelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Physical TherapistsDocument9 paginiWork-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Physical TherapistsDr. SheikhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prevalence de TmsDocument7 paginiPrevalence de TmszouhireamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trauma Informed Care in Medicine: Current Knowledge and Future Research DirectionsDocument11 paginiTrauma Informed Care in Medicine: Current Knowledge and Future Research DirectionsJohn BitsasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nursing Management of Emergency Department Violence - Can We Do More?Document8 paginiNursing Management of Emergency Department Violence - Can We Do More?margi13Încă nu există evaluări

- Aggression and Violent Behavior: Nathalie Lanctôt, Stéphane GuayDocument10 paginiAggression and Violent Behavior: Nathalie Lanctôt, Stéphane GuayÁngela María GuevaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workplace Violence in Healthcare Settings: Risk Factors and Protective StrategiesDocument8 paginiWorkplace Violence in Healthcare Settings: Risk Factors and Protective StrategiesÁngela María GuevaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Title Page Title: Workplace Violence Perpetrated by Clients of Healthcare: A Need For Safety andDocument26 paginiTitle Page Title: Workplace Violence Perpetrated by Clients of Healthcare: A Need For Safety andÁngela María GuevaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workplace Violence Among Health Care Workers: Artículo de RevisiónDocument10 paginiWorkplace Violence Among Health Care Workers: Artículo de RevisiónÁngela María GuevaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Workplace Violence in HealthcareDocument5 paginiWorkplace Violence in HealthcareÁngela María GuevaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oezcan M Gresnigth M J Can Dent Assoc 2011Document9 paginiOezcan M Gresnigth M J Can Dent Assoc 2011Ángela María GuevaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Original Research Article Impact and Prevalence of Physical and Verbal Violence Toward Healthcare WorkersDocument7 paginiOriginal Research Article Impact and Prevalence of Physical and Verbal Violence Toward Healthcare WorkersÁngela María GuevaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coachman Calamita DSD Eng 12 PDFDocument10 paginiCoachman Calamita DSD Eng 12 PDFÁngela María GuevaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ejed 9 3 Tirlet p354Document16 paginiEjed 9 3 Tirlet p354Ángela María GuevaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Articulo Pascal Magne Color, Forma Etc.Document24 paginiArticulo Pascal Magne Color, Forma Etc.Andrea Paola Fumero100% (1)

- Mapeh 8 Semi-FinalsDocument4 paginiMapeh 8 Semi-FinalsDian Legaspi0% (1)

- Application of Theory in Nursing ProcessDocument19 paginiApplication of Theory in Nursing ProcessCurly AngehÎncă nu există evaluări

- Participant Processing GuideDocument64 paginiParticipant Processing Guideleonard opheim100% (1)

- Vulnerability Assessment ToolDocument43 paginiVulnerability Assessment ToolAdnan Hossain0% (1)

- Facts and Figures From PDEA Catchillar Stephanie L. NSTPDocument5 paginiFacts and Figures From PDEA Catchillar Stephanie L. NSTPJovilleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Journal Substance AbuseDocument7 paginiJournal Substance AbuseParas AzamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2011-2021Document89 paginiYouth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2011-2021ABC7NewsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dangers of Drug AbuseDocument3 paginiDangers of Drug AbuseVikas S nÎncă nu există evaluări

- Depression and Anxiety Among College StudentsDocument2 paginiDepression and Anxiety Among College StudentsAnonymous 5WUUQijWÎncă nu există evaluări

- Psychological Consequences of Sexual TraumaDocument11 paginiPsychological Consequences of Sexual Traumamary engÎncă nu există evaluări

- Premarital Counseling QuestionnaireDocument13 paginiPremarital Counseling QuestionnaireMoabiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Work Case Studies Foundation Year 1Document1 paginăSocial Work Case Studies Foundation Year 1Marian Nuñez-SierraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oct 109Document40 paginiOct 109mwmccarthyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Standard Parole ConditionsDocument1 paginăStandard Parole ConditionsWXYZ-TV Channel 7 DetroitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mental HealthDocument16 paginiMental HealthnataliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Opioid Dependence GuidelinesDocument136 paginiOpioid Dependence Guidelinesanto100% (1)

- NCP AnxietyDocument4 paginiNCP Anxietycathy100% (2)

- Critical Appreciation of Poems and Other LessonsDocument14 paginiCritical Appreciation of Poems and Other LessonsSHIMNAS EÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Drugs AddictionDocument5 paginiThesis Drugs Addictiondianaturnerspringfield100% (2)

- Clean and Sober A Study On The Well-Being of The Clients Inside A Rehabilitation Center in Ozamiz City, Misamis OccidentalDocument84 paginiClean and Sober A Study On The Well-Being of The Clients Inside A Rehabilitation Center in Ozamiz City, Misamis OccidentalBimby Ali LimpaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Knowledge and Attitude of Youths To Substance Abuse in Alimosho Local Government Area of Lagos StateDocument15 paginiKnowledge and Attitude of Youths To Substance Abuse in Alimosho Local Government Area of Lagos StateAmit TamboliÎncă nu există evaluări

- CRAFFTDocument24 paginiCRAFFTRani HusainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Muzzo Parole Board DecisionDocument8 paginiMuzzo Parole Board DecisionCTV NewsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prescription Drug Misuse GuideDocument25 paginiPrescription Drug Misuse GuideSdÎncă nu există evaluări

- BE Aware!: Q. What Is Drug Abuse?Document3 paginiBE Aware!: Q. What Is Drug Abuse?Dainielle Marie PascualÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Pro 3 (Official)Document2 paginiNew Pro 3 (Official)AARON JED RECUENCOÎncă nu există evaluări

- The California Child Abuse & Neglect Reporting Law: Issues and Answers For Mandated ReportersDocument57 paginiThe California Child Abuse & Neglect Reporting Law: Issues and Answers For Mandated Reportersmary engÎncă nu există evaluări

- University of Cambridge, Institute of Criminology Radzinowicz Library ClassmarksDocument37 paginiUniversity of Cambridge, Institute of Criminology Radzinowicz Library ClassmarksFuzzy_Wood_PersonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Advertisement ONE (Educating People On How To Accept Them)Document11 paginiAdvertisement ONE (Educating People On How To Accept Them)Vivek RaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Community Guidelines - TikTok - March 2023 - Regulated GoodsDocument5 paginiCommunity Guidelines - TikTok - March 2023 - Regulated GoodsAline IraminaÎncă nu există evaluări