Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Hafner - 1969 - The New Reality in Art and Science

Încărcat de

EyeVeeDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Hafner - 1969 - The New Reality in Art and Science

Încărcat de

EyeVeeDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The New Reality in Art and Science

Author(s): E. M. Hafner

Source: Comparative Studies in Society and History , Oct., 1969, Vol. 11, No. 4, Special

Issue on Cultural Innovation (Oct., 1969), pp. 385-397

Published by: Cambridge University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/178070

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Comparative Studies in Society and History

This content downloaded from

132.204.251.254 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 23:14:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The New Reality in Art and Science

E. M. HAFNER

Hampshire College

We are often told, and it is easy to believe, that the im

art are not drawn from the real world. In the most conventional view

of the modern school, abstract painting is a search for free expression

of the artist's own vision. The non-representational painter works as he

pleases and is pleased by little that he sees. A humorous drawing in a

sophisticated magazine shows a studio full of wild canvases, with the

artist gazing through the window at a magnificent sunset. He says to a

friend, 'Yes, old man, I admit that it's beautiful. Sometimes I'm sorry

it's not the sort of thing I do.' Authority for the establishment of a public

attitude that makes such a joke possible is to be found in the writings

of many critics and in the words of artists themselves. Harold Rosenberg:

'The big moment [in art] came when it was decided to paint-just to paint.

The gesture on the canvas was a gesture of liberation from value, political,

aesthetic, moral.' Andre Malraux: 'What then was painting becoming,

now that it no longer imitated or transfigured? Simply-painting.'

Sheldon Cheney: 'I cannot do better, in trying to help you to an under-

standing of modernism, than to point out the devastating effect the realistic

movement had on the arts as a whole.' Piet Mondrian: 'In order that

art ... should not represent relations with the natural aspect of thin

the law of the denaturalization of matter is of fundamental importance.'

Clive Bell: 'Creating a work of art is so tremendous a business that

leaves no leisure for catching likenesses.' Kasimir Malevich: 'From

the supremist point of view, the appearances of natural objects are in

themselves meaningless... The representation of an object ... is

something that has nothing to do with art.' Laurence Binyon, in 1911:

'The theory that art is, above all things, imitative and representative, no

longer holds the field with thinking minds.' Ortega y Gasset: 'Painting

completely reversed its function and, instead of putting us within what is

outside, endeavored to pour out upon the canvas what is within: ideal

invented objects.' And Camille Graser, in a letter which we shall be

examining in detail: 'In all of my work ... there exists no dependence

c 385

This content downloaded from

132.204.251.254 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 23:14:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

386 E. M. HAFNER

on the tangible environment, in spite of the fact that I love nature very

much.'

Statements of this kind gather strength from a variety of aesthetic

doctrines, the most common of which suggests that the painter avoids

imitation of nature by emulating something else, something that is

presumably subjective and abstract in its very essence. We are urged, for

example, to accept music as a model of the arts:

It is almost impossible to state any theory of the abstract in art without resource to

the terminology and the parallel of music. For music is a wholly non-representative

[sic] art based in its physical aspect on certain widely understood phenomena. The goal

of the abstract painters is an art of color as free from associative and objective interest

as is this other art of sound.... Painting must be stripped of the trivial and extran-

eous elements that give rise to the pleasures typical of drama, anecdote, photography,

etc.'

The argument appears to be that music is non-representational, that it is

nonetheless in some sense artistically valuable, that there is no essential

need for depiction of natural objects in painting, and that a painter's

'goal' of freedom from 'associative and objective interest' is therefore

respectable. What we are not told, of course, is why an absence of 'trivial

and extraneous elements' should be the mark of the purest and best in art

or, for that matter, why music should be of any aesthetic interest to us

in the first place. The fact that modern music appears to be in a state of

artistic crisis is not helping us to answer such questions with confidence.

One can look to composers themselves for an account of their art; one

finds statements like this:

We included in the Computer Cantata representative examples of the various significant

categories of electronic sound. In each case, we deliberately selected the simplest

example of each. .... For ordinary electronic sounds, we selected, first, the three most

basic periodic signals, namely, sine tone ... square wave .. and sawtooth wave, and,

second, two types of noise, namely, white noise and ordinary noise. This ordinary noise,

which we called for convenience 'colored noise', was represented by eight characteristic

recorded concrete sounds designated in the score by the mnemonic signs, CLICK, CLACK,

SISS, CRACKLE, SNAP, POP, BANG and BOOM. The third category of electronic sound was,

of course, synthesized by means of the CSX-1 computer.2

No wonder, perhaps, that Henry Pleasants reached the conclusion that

serious music is a dead art whose last truly modern exponent was Wagner,

following whom everything has been 'reaction, refinement, and desperate

experimentation'. Paul Hindemith expressed his complaint this way:

A group of composers, in an attempt to replace with an apparent rationality what is

lacking morally, develops an over-sublimated technique which produces images and

emotions that are far removed from any emotional experience a relatively normal human

1 Sheldon Cheney, A Primer of Modern Art (New York: Liveright, 1958), p.159.

2 L. A. Hiller and R. A. Baker, 'Computer Cantata: A Study in Compositional Method',

Perspectives of New Music, Fall 1964, p.65.

This content downloaded from

132.204.251.254 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 23:14:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE NEW REALITY IN ART AND SCIENCE 387

being has ever known. In doing so they advocate the esoteric art pour l'art, the followers

of which can only be emotional imps, monsters and snobs.3

If modern music as a model of artistic abstraction draws frequent hostile

fire, concurrent trends in painting are often no more kindly received:

Most of the mushrooming art movements seem to have forgotten the essential role of

artistic creation. By and large, the art world has become the scene of a popularity contest

manipulated by appraisers and impresarios who are blind to the fundamental role of

the artistic image ... [Artists] come together in small groups in great cities where, in

the safety of little circles that shut out the rest of the world, the initiates share one

another's images. They generate illusory spontaneity, but miss the possible vital con-

nections with ... reality.4

Mourning the retreat of modern art from the world of sensible experience,

these critics (many of whom are artists as well) express a view of the matter

that is widely shared by laymen. Putting aside those who regard most of

current art as a rude and expensive hoax 'manipulated by appraisers',

many thoughtful people of our time find themselves unable to give serious

attention to modern trends in painting. The artist seems-and often

claims-to have left the real world behind him in a search for the meaning

of his own complex subconsciousness. Scholarly jargon, with such terms

as analytical cubism, geometric constructivism, and abstract expressionism,

carries frightening overtones of a discipline that has contracted into an

austere and private domain.

I wish to begin a study of this situation by pointing to the striking

similarity between the layman's view of modern art and his view of

modern science. Here, for example, is a statement about science:

Our twentieth-century world, with its swift technological and scientific advances and

socio-economic upheavals, our century which has witnessed the rapid shrinking of

the world's dimensions, is obligated to give its children a view of science which reflects

these changes. Yet today the average man, who may occasionally be led to cast a casual

glance in the direction of abstract science, still sees it as a mental challenge that is both

revolutionary and startling-at times irritating and aggressive, and at other times

meaningless or merely innocuous and inoffensive.5

Does this not express in familiar terms the impasse between layman

and scientist? It is, in fact, a statement dealing with abstract painting; I

have merely changed a few words, substituting science for art. The lay-

man looks at both of these esoteric worlds with confusion and dismay,

puzzled and intrigued by the insistence of the experts that something of

enormous significance is taking place beyond his ken.

What seems to disturb a layman most about abstract painting is its

3 Paul Hindemith, A Composer's World (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1953), p. 43.

4 Gyorgy Kepes, 'The Visual Arts and the Sciences', in Science and Culture (Boston:

Houghton Mifflin, 1965), p. 148.

5 Paraphrase from Michel Seuphor, Abstract Painting (New York: Dell Publishing Com-

pany, 1964), p. 7.

This content downloaded from

132.204.251.254 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 23:14:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

388 E. M. HAFNER

studied avoidance of recognizable image; what disturbs him about science

is the inaccessibility of its language, which also seems to present itself

as an avoidance of the recognizable. In fact, the departure of modern

physics from common notions of reality is urged upon him by many

popularizers of the current trend. Speaking of the quantum mechanical

view of matter, Arthur Koestler says 'These waves . . . travelling through

a non-medium in multi-dimensional non-space are the ultimate answer

modern physics has to offer to man's question after the nature of reality.'6

On the same subject Jeans says:

The concepts which now prove to be fundamental to our understanding of nature .. .

seem to my mind to be structures of pure thought, incapable of realization in any sense

which would properly be described as material.7

Bertrand Russell has expressed the idea that an abstract view of the world

is the only one possible: 'Physics is mathematical not because we know

so much about the physical world, but because we know so little. It is

only its mathematical properties that we can hope to discover.' And

Eddington tells us that, in studying the physical world, we are only

studying ourselves:

... we have found that where science has progressed the farthest, the mind has but

regained from nature what the mind has put into nature. We have found a strange

footprint on the shore of the unknown. We have devised profound theories, one after

another, to account for its origin. At last, we have succeeded in reconstructing the

creature that made the footprint. And Lo! it is our own.8

Strikingly similar to this is a statement by the constructivist sculptor

Naum Gabo:

There is nothing in nature that is not in us. Whatever exists in nature exists in us in

form of our awareness of its existence. All creative activities of mankind consist in the

search for an expression of that awareness.9

The conviction shared by Eddington and Gabo, speaking for science

and art respectively, is that our image of nature is an image of ourselves.

Let us suppose that this is true. What then becomes of the concept of

reality? It is evidently not a fixed substratum of perception toward which

we probe with ever sharper tools, but a shifting set of concepts dependent

on the depth of our perception and the character of our probes. The real

world of Aristotelean physics was not merely reinterpreted, but to a large

degree replaced by the real Newtonian world, which has in turn been

replaced by the new world of relativity and quantum mechanics. Before

the modern sequence of astronomical observation which began with

6 Arthur Koestler, The Sleepwalkers (New York: Macmillan, 1959), p. 531.

7James Jeans, The Mysterious Universe (Cambridge, 1930), p. 146.

8 A. S. Eddington, Space, Time and Gravitation (Cambridge, 1953).

9 Naum Gabo, 'Art and Science', in The New Landscape (Chicago: Paul Theobald, 1956).

This content downloaded from

132.204.251.254 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 23:14:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE NEW REALITY IN ART AND SCIENCE 389

Galileo, structural features of the earth were unique among objects of

the real universe. Before the discovery of variable luminosities and reces-

sional redshifts, the stars were truly fixed in a celestial sphere.

Each new scientific probe gives us a new reality, whose images are

bewildering until' they become commonplace. Radiographs of familiar

objects would be mysterious and disturbing to observers accustomed only

to external surfaces. Microphotographs of organic structures are recog-

nizable and informative images of reality to the trained eye; studies of

strained plastics in polarized light make visible a strange world at the

interior of matter. Even without elaborate optical tools, we see a changing

scene with every changing perspective. When we move close to a fracture

in glass, or far from a landscape, we discover new patterns in familiar

things. And we find the stimulus of new patterns in every unfamiliar

object even at the distance of normal vision.

Just as the shifting objectivity of science brings us a new subjective

view, the interpretations and abstractions of graphic art reveal unsuspected

nuance in reality. 'One can say that although the color-saturated atmo-

sphere of Paris is older than the city itself, its beauty was first revealed by

the Impressionists. Or again, tessellated floors existed in Italy long before

their beauty was revealed by the Quattrocentro painters with their passion

for perspective.'10 Whether we speak of science or art, we recognize

the essential role played by revolution. Every epoch is marked by its

current paradigms: coherent traditions of observation and interpretation

which set the stage for normal activity. But every epoch ends in revolution,

after which the old paradigms give way to the new. Whenever this happens,

it is fair to say that the real world itself has changed. Here is an expression

of that idea:

Examining the past from the vantage of contemporary historiography, the historian

may be tempted to exclaim that when paradigms change, the world itself changes with

them. Led by a new paradigm, we adopt new techniques and look in new places. Even

more important, during revolutions we see new and different things when looking with

familiar techniques in places we have seen before. It is rather as if the professional

community had been suddenly transported to another planet where familiar objects

are seen in a different light and are joined by unfamiliar ones as well. Of course, nothing

of quite that sort does occur: there is no geographical transplantation; outside the

workroom everyday affairs continue as before. Nevertheless, paradigm changes do

cause us to see the world of our engagement differently. In so far as our only recourse

to that world is through what we see and do, we may want to say that after a revolution

we are responding to a different world.11

Is this a statement about changing patterns of science or about revolu-

tions in artistic perception? It might easily be either; actually, with a few

10 Georg Schmidt and Robert Schenk, eds., Kunst und Naturform (Basel: Basilius Presse,

1958).

u Paraphrase from T. S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University

of Chicago Press, 1962).

This content downloaded from

132.204.251.254 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 23:14:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

390 E. M. HAFNER

minor alterations, it is T. S. Kuhn's assessment of the way in wh

scientific revolutions change our view of the world.

The more carefully we try to distinguish artist from scientist, the m

difficult our task becomes. Looking first at the words themselves, we

'skill' as a primitive synonym for 'art', and 'knowledge' for 'science

science falls to pieces without skill in observation and analysis; art with

knowledge is puerile. We may point to a high level of creativity as the

mark of art, suggesting that science is more the work of passive discov

But the artist's development is largely a process of self-discovery,

creative work of the highest calibre is possible (and essential) withi

framework of science. A set of aesthetic values has sustained much scie

an appreciation and an exploitation of quantitative structure find

way easily into art. Both activities are commitments to a sturdy sense

discipline, while at the same time neither is free from elements of cha

and simple good fortune. It is even difficult to distinguish art from sc

through a comparison of their principal aims. Paul Klee once asked

self to what extent and with what purpose the artist should con

himself with new scientific images of the world. He suggested that it

done

... only for purposes of comparison; only in the exercise of his mobility of mind.

Only in the sense of a freedom which does not lead to a fixed development, representing

exactly what nature once was, or will be, or could be on another star. But in the sense

of a freedom which merely demands its rights, the right to development as flexibly as

nature herself.12

This idea-that the motive for studying existing knowledge is the develop-

ment of intellectual mobility-is of course a scientist's principal credo

as well, and Klee's advice may apply with equal force to the scientist in

contemplation of artistic image.

Do the graphic images themselves, emerging from laboratory and

studio, betray their scientific or artistic origins? In most cases they do:

visual clues in enormous number and variety lead us to a quick decision.

There is no way of confusing Leonardo's anatomical sketches with the

Mona Lisa, even though the portrait contains a strong element of physio-

gnomic analysis. But it is an interesting and incontrovertible fact that the

newest images of science and art are easily confused except by very special

eyes. An observer attuned to Japanese prints and unaware of X-radio-

graphy might most comfortably see a radiogram of a lily as a delicately

idealized sketch from life, and many microphotographs might strike

almost anybody as abstract expressions of free artistic imagination. Let us

suppose that such a microphotograph were included without identification

12 Paul Klee, 1924 speech at Jena, reprinted in Modern Artists on Art (Englewood Cliffs,

N.J.; Prentice-Hall, 1964), p. 88.

This content downloaded from

132.204.251.254 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 23:14:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE NEW REALITY IN ART AND SCIENCE 391

in an exhibit of modern drawings. Could it not be praised and

by professional critics, and received with the usual apathy or i

by laymen who see such works as sloppy drawings of noth

we not hear an artist exclaim, 'I wish I had done that!' and f

subsequent work was influenced by it? Would the experience n

that the views of Rosenberg, Malraux, Cheney, Mondrain, Bell

Binyon, and Ortega are blind to a deep relation between scie

And that Russell, Eddington, Gabo, Klee, and Kuhn are ge

bottom of things ?

Looking back once again 'from the vantage of contempora

graphy', we are constantly reminded that man's several kinds

activity are reflections of each other. All are engaged in a com

for ways of expressing our awareness of ourselves and of t

imagine to exist outside of ourselves. The Pythagorean noti

mathematics is a common key to science and art is perhap

example of this view of creative unity. It has been more or

at work through the ages down to our own time. For exam

have always derived stimulus from pure geometry, as can b

paintings of Kandinsky, and an analogous stimulus ha

astronomy, as in the evolution of general relativity. The gr

of geometrical influences on science is exhibited as much b

have failed as it is by occasional success. Kepler's lifelong

connection between solid geometry and the solar system

error, but at the same time forced him into a position from w

see another way to the truth.

While it can be asserted without question that art and s

the same conceptual material, it is far less certain that the

has exerted direct influence on the work of the other. W

obsessions strengthened by the music and the graphic art

Is it an accident that, in the work of both Raphael and Cop

earth loses its place at the center of the universe and man his

in creation? And, in our own time, is it by chance that b

science have abandoned the world of familar form in a search for new

perspective? These questions are easier to raise than they are to answer

in convincing terms, despite a large and growing literature on the subject.

Let us begin with a sampling of opinion. Here is a remarkable statement

by Leo Steinberg, who feels that the influence is direct and essential:

Wittingly, or through unconscious exposure, the non-objective artist draws much of

his iconography from the visual data of the scientist-from magnifications of minute

natural textures, from telescopic vistas, submarine scenery and X-ray photographs....

Where the Renaissance had turned to nature's display windows, and to the finished

forms of man and beast, the men of our time descend into nature's laboratories. But the

affinity with science probably goes further still. It has been suggested that the very

concepts of twentieth-century science are finding expression in modern abstract art. ..

This content downloaded from

132.204.251.254 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 23:14:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

392 E. M. HAFNER

not because painters illustrate scientific concepts, but because an awareness of na

in its latest undisguise seems to be held in common by science and art.13

Naum Gabo takes an equally positive view:

However dangerous it may be to make far-reaching analogies between art and sci

we nevertheless cannot close our eyes to the fact that at those moments in the hi

of culture when the creative human genius had to make a decision, the forms in w

this genius manifested itself in art and science were analogous.... Even for m

theorists of art the fact remains unperceived that the same spiritual state propels art

and scientific activity at the same time and in the same direction.14

Gyorgy Kepes, who has already been represented here with the remark

that much of modern art is a 'popularity contest manipulated by ap

sers . . blind to the fundamental role of the artistic image', neverth

sees a profound but misunderstood relation to science:

Because our modern specialization so often separates artist and scientist, neith

fully aware of the profundity of the other's work. Both reach beneath surface pheno

to discover basic natural pattern and basic natural process; yet the scientist ex

the artist to interpret literally and the artist expects the scientist to think mechanica

Robert Schenk provides us with typical expression of an intermed

position:

To seek direct and mutual influences behind the occasionally striking coincidences

between art and science is certainly to overlook their true relationship. The artist is

no more inspired in his work by the microcosmos than the scientist allows aesthetic

considerations to influence his. The real reason for these apparent formal coincidences

is surely to be found in the intellectual climate in which both art and science function

today.17

Standing in stark opposition to Steinberg and Gabo are strong denials of

such influence. Some are uttered by artists themselves. A few years ago,

Rosamond Bernier asked the constructivist sculptor, Antoine Pevsner,

about the apparent mathematical basis in his work. He said:

... I am glad to have a chance to clear up this matter. My work has nothing to do with

mathematics or science, although scientists say we are searching in the same direction.

But they search for the laws of the universe according to calculations, while I base

myself on pure art. My sculpture uses no figures or formulas, although scientists try

to find them in my work.18

Pevsner's view is shared by many artists who speak of 'pure art', 'liberation

from value', 'denaturalization of matter', and 'ideal invented objects'.

The tone of such statements is often cranky and defensive, suggesting

13 Leo Steinberg, 'The Eye is a Part of the Mind', Partisan Review, 20, 194 (1953), p. 194.

14 Naum Gabo, 'The Constructive Idea in Art', in Modern Artists on Art, op. cit, p. 105.

15 See note 4.

16 Gyorgy Kepes in The New Landscape, op. cit.

17 Robert Schenk in Kunst und Naturform.

18 From a 1957 conversation with Antoine Pevsner, published in Aspects of Modern Art

(New York: Reynal and Co., n.d.).

This content downloaded from

132.204.251.254 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 23:14:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE NEW REALITY IN ART AND SCIENCE 393

that the artist is almost afraid of objective and imitative elements in h

work. They also frequently reveal an ignorance of science. We won

for example, if Pevsner sees only calculations, figures, and formulas in

scientific search for universal law.

A most extraordinary collection of comparisons between microphoto-

graphs and works of abstract art appeared at the Kunsthalle, Basel, in

1958. The examples, together with a set of interpretive essays, have been

reproduced in a beautiful volume.19 One sees the n-hexatriacontane

crystal compared with a Honegger composition; trabeculae of the human

tibia with Max Bill's spatial rhythms; blood vessels of the kidney with

Clifford Still's organic structures; cells of the cerebrum with Schulze's

vision of meteors; nasal conchae with Kandinsky's capricious forms; and

many other provocative examples. The resemblances are sometimes utterly

shocking. Although the aim of the exhibition was to exploit such like-

nesses as boldly as possible, the simple fact that dozens of close parallels

could be found suggests that we cannot easily dismiss them as accidents.

They cry out for another explanation.

We might at first suspect that the artists have merely returned to nature,

filling their canvases deliberately with a new scientific landscape. Georg

Schmidt20 argues against this:

The inveterate opponents of non-representational art greeted the exhibition trium-

phantly as a giveaway: 'There you are! We always said non-representational art was

nothing but a new and commonplace form of naturalism....' If this objection were

valid it would mean that these painters were familiar with scientific photomicrography

before they went over to non-representational painting. But in fact the sequence of

events was the precise opposite. ... The fascinating beauty of form in photographs of

crystal and organic microstructure was perceived only after painters had discovered

the ordered world of extra-objective forms. The most one can say is ... that science,

pursuing its own course, had arrived at results which were formally similar to those

achieved by modern art....

Some of the painters themselves, even when confronted with such examples

involving their own work, hold to their doctrinaire abstractionist positions.

One of the most striking comparisons in the Basel exhibition showed

almost identical compositions of aspartic acid crystals on the one hand

and a constructivist painting by Camille Graser on the other. In response

to an inquiry about the influence of science on her work, Miss Graser

has written us a statement of which the following is a part:

The exhibit in Basel was a surprise. The parallels could not have been presented in a

more beautiful fashion; the world of the microcosm was fascinating. In the beginning, I

feared misconceptions and a confusion of principles of art. In all of my work, which is

'constructive-non-objective', there exists no dependence on the tangible environment,

in spite of the fact that I love nature very much. My concern in painting is the forming

of a new reality. My work is based on elements of form and number, and on the

19 See note 10. 20 Ibid.

This content downloaded from

132.204.251.254 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 23:14:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

394 E. M. HAFNER

analyzed light of the spectrum. Thus, stimulus from the microcosm is unthinkab

it would mean an erring deviation from my theory and would put upon me the

of a renegade naturalist. I believe that the newly won consciousness rests on the re

tion that the discovery of scientific truth on the one hand, and the creations of mod

art on the other, represent continual and searching advances on two dramati

opposed paths.21

Miss Graser's passionate denial of scientific influence is extraordina

several respects. She tells us that such stimulus is 'unthinkable', in a to

suggesting that if she were to deviate from the aesthetic principles of

group, she would run the risk of ostracism and contempt. Also, she app

to be caught in currents of quasi-scientific jargon so swift and perv

in our time as to threaten us all. Her statement is to this extent self-

contradictory: to work with 'elements of form and number, and ... the

analyzed light of the spectrum' is to recognize the tools of science; to be

concerned with 'the forming of a new reality' is to recognize the spirit of

science and its aims.

If these resemblances were not produced by chance or by conscious

imitation, how are we to account for them? Why have scientific studies of

a domain where ordinary vision fails given us images resembling 'abstract'

painting, some of which preceded the photographs? We have already

noted Schenk's view22 that the explanation lies 'in the intellectual climate

in which both art and science function today'. Dealing with the problem

of visualizing modern science, Steinberg23 arrives at the same conclusion:

The question is, of course, whether nature as the modern scientist conceives it can be

represented at all, except in spectral mathematical equations. Philosophers of science

concur in saying it cannot.... 'Our understanding of nature has now reached a

stage', says J. W. N. Sullivan, 'where we cannot picture what we are talking about'.

But this utterance of the philosophers contains an unwarranted assumption: that

whereas man's capacity for intellectual abstraction is ever widening, his visual imagina-

tion is fixed and circumscribed. Here the philosophers are reckoning without the host,

since our visualizing powers are determined for us not by them but by the men who

paint. Our visual imagination, thanks to those in whom it is creative, is also in perpetual

growth.... Thus the art of the last half century may well be schooling our eyes to

live at ease with new concepts forced upon our credulity by scientific reasoning.

It might at first seem that this positon is tenable only if the artist's role

is consciously didactic, aimed toward showing us how the new reality of

science can be brought within a comfortable visual compass. But to

accept this premise is to vitiate the idea, especially if we take the artist

at his own word. Gabo may insist that 'the same spiritual state propels

artistic and scientific activity', but he speaks for a tiny minority. Ranged

against him are the multitudes of Pevsners and Grasers, not to mention

the majority of art theorists and the entire apparatus of public relations

21 Translation of a letter from Camille Graser. I am indebted to Susan Presswood Wright

for her assistance in soliciting this statement.

22 See note 17. 23 See note 13.

This content downloaded from

132.204.251.254 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 23:14:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE NEW REALITY IN ART AND SCIENCE 395

in the galleries and academic departments of art. Thus, if Steinberg's

thesis is correct it nevertheless demands a symbiotic relation of extra-

ordinary power, capable of withstanding widespread and vigorous dis-

claimers of its very existence.

At the same time, we must realize that an artist's or a scientist's account

of his activities can easily miss the mark. Without necessarily intending to

mislead or to deceive us, he is compelled to explain himself within a pattern

of thought and expression fixed by a current set of paradigms and colored

by his prejudices. The process of creative discovery is essentially tentative

and confused, the clearest vistas being always backward. Koestler has

shown us the scientist as sleep-walker, stumbling toward insights which

prior doctrine has taught him to resist. We can understand, then, that the

creative arts move forward even more tentatively, and with even less

awareness of discovery. And added to conceptual uncertainty in both

science and art is an inadequacy of the language into which forms of

explication must somehow be made to fit. If scientific models and works

of art are themselves metaphorical descriptions of the world, our linguistic

treatments of them take us one more step away from our primitive

material, and tend to produce esoteric languages that are difficult to

conjoin. In von Humboldt's terms, 'By the same process whereby man

spins language out of his own being, he ensnares himself in it; each

language draws a magic circle round the people to which it belongs, a

circle from which there is no escape save by stepping out of it into an-

other'.

I wish therefore to propose that we can best approach the question

before us by paying relatively little attention to the utterances of critics

and philosophers of art and science, concentrating instead on the works

themselves. They speak to us directly, whenever we take the trouble to

observe them with trained sensitivity. If there is an element of science in

Camille Graser's paintings, it speaks for itself independently of the

language in which she denies it. If there is an aesthetic element in the

crystal photograph, it also speaks for itself independently of the purely

scientific language in which it is understood by crystallographers. Thus,

instead of searching wistfully for a common language that will somehow

subtend the two 'magic circles' of artistic and scientific philosophy, we

can fix our gaze directly on art and science. Then, as free as possible from

the distraction of unnecessary metaphor, we may see most clearly how

art and science shape the world of our perception, each in its own way.

We may also arrive at a clearer understanding of how and to what extent

they shape each other.

Facing the evidence on these terms, I am drawn strongly to the con-

clusion that the abstract forms of modern art are largely a result of

sympathetic vibration with concurrent trends toward abstraction in

This content downloaded from

132.204.251.254 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 23:14:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

396 E. M. HAFNER

science. It is impossible today, just as it has always been in the history of

our culture, for the artistic intellect to insulate itself from conceptual

revolutions. When the winds of science shift to a new quarter, everything

in their path bends a little; when we look at the resulting commotion, we

see an image of the wind itself. The response is inevitable at some sub-

conscious level even when the stimulus is unrecognized. An artist need no

more understand mathematical physics than the waving grain understands

meteorology. And we can witness and profit from the response without

understanding the subtle forces which produce it.

Let us turn, finally, to the other side of the question. To what extent

can the artistic imagination, as free from outside influences as possible,

develop forms and concepts which became subsequently imbued with

scientific meaning? We are, of course, well aware of the stimulus to

science provided by classical forms of art, brought most vividly to light

in great works of the Renaissance. Geometrical objects of highest value to

science appear in every period of art history; there can be little doubt

that their artistic treatment gave force to the early periods of mathematics,

physics, and astronomy. Indeed, some of the problems suggested by the

work of great masters have persisted undiminished into our time. There is

the problem of reflection symmetry, revolutionized by current discoveries

in microscopic physics after being brought to artistic consciousness by

such works as Michelangelo's 'Creation of Adam'. The artist shows the

right hand of God imparting life to the left hand of man; the physicist

asks himself whether a corresponding asymmetry can be found in the laws

of nature, and eventually discovers that the neutrino is left-handed. Yet

the asymmetry, as in the painting, is subtle and difficult to understand-a

small nuance in an overwhelmingly symmetrical world. Here is a pro-

vocative statement of the question, referring us to another work of art:

. . Our problem is to explain where symmetry comes from. Why is nature so nearly

symmetrical? No one has any idea why. The only thing we might suggest is something

like this. There is a gate in Japan, a gate in Neiko, which is sometimes called by the

Japanese the most beautiful gate in all Japan; it was built in a time when there was great

influence from Chinese art.... But when one looks closely he sees that ... one of the

small design elements is carved upside down; otherwise the thing is completely sym-

metrical. If one asks why this is, the story is that it was carved upside down so that the

gods will not be jealous of the perfection of man.24

But since the discovery that nature herself is not quite symmetrical, it is

tempting to turn the idea around: 'We might. .. think that the true

explanation of the near symmetry of nature is this: that God made the

laws only nearly symmetrical so that we should not be jealous of His

perfection!'

24 R. P. Feynman, 'The Feynman Lectures on Physics', Vol. I (Reading: Addison-Wesley,

1963).

This content downloaded from

132.204.251.254 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 23:14:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE NEW REALITY IN ART AND SCIENCE 397

It is possible to assert that modern abstract art is continuing and

ing the classical tradition, producing occasionally in its own way an

containing clues to new scientific reality. Try as he may to fre

from nature, the artist earns no more than 'the right to develop a

as nature herself'. Thus his ideas, however fanciful and whatever h

presume their origins to be, can eventually become identified as pr

of scientific insight. He cannot help breathing the atmosphere of h

inhaling the new fresh air of science and exhaling, after complex a

metabolism, a new artistic metaphor. There is frequent nonsen

world of art-trumpery, hypocrisy, venality, and commercialism b

on criminality. And there are all these things in the world of s

well. But the essential values of both are still with us, sustain

culture now as they have in the past. Their magic circles of langua

and perhaps should not mix; our sensitive perception is the bridge

them. Especially in view of the extraordinary success with which m

man has turned speculative fancy into a true vision of the world, s

not turn Gabo's precept into its converse: 'There is nothing in u

not in nature'?

This content downloaded from

132.204.251.254 on Wed, 16 Sep 2020 23:14:19 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Anywhere or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary ArtDe la EverandAnywhere or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary ArtEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Fluxus Performance WorkbookDocument60 paginiFluxus Performance Workbookgnjanica84100% (1)

- InterviewsDocument182 paginiInterviewsGabriel BerberÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Creative ActDocument6 paginiThe Creative ActTheo LafleurÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Magic of AntennasDocument9 paginiThe Magic of AntennasEyeVeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Why Does Art Matter? Intellect's Visual Arts SupplementDocument21 paginiWhy Does Art Matter? Intellect's Visual Arts SupplementIntellect Books100% (4)

- Visual ArtsDocument40 paginiVisual Artsricreis100% (2)

- Surrealism and Music Seminar2008Document56 paginiSurrealism and Music Seminar2008Leandro A. AragonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nature of Abstract ArtDocument15 paginiNature of Abstract ArtHamed KhosraviÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fluxus Build Manual DiyDocument8 paginiFluxus Build Manual DiyEyeVeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- FIRST-TERM FORM TEST (2020/21) Form Two Integrated Science: Instructions Multiple-Choice Answer SheetDocument14 paginiFIRST-TERM FORM TEST (2020/21) Form Two Integrated Science: Instructions Multiple-Choice Answer SheetYuki LiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Judith Adler - Revolutionary ArtDocument19 paginiJudith Adler - Revolutionary ArtJosé Miguel CuretÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Origin of The Work of Art: Modernism: Heidegger'sDocument19 paginiThe Origin of The Work of Art: Modernism: Heidegger'siulya16s6366Încă nu există evaluări

- 8 - Bus Mackie Service ManualDocument8 pagini8 - Bus Mackie Service ManualEyeVeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Natasa Vilic-Pop-Art and Criticism of Reception of VacuityDocument15 paginiNatasa Vilic-Pop-Art and Criticism of Reception of VacuityIvan SijakovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alchemy and Art During The Sixteenth Seventeenth Centuries PDFDocument180 paginiAlchemy and Art During The Sixteenth Seventeenth Centuries PDFAnamaria TîrnoveanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Promoting Self Esteem: Presented by Shilpa Hotakar MSC Nursing Dept of Psychiatric NursingDocument23 paginiPromoting Self Esteem: Presented by Shilpa Hotakar MSC Nursing Dept of Psychiatric NursingShilpa Vhatkar0% (1)

- A Course of Theoretical Physics Volume 1 Fundamental Laws Mechanics Electrodynamics Quantum Mechanics-A.S. Kompaneyets PDFDocument574 paginiA Course of Theoretical Physics Volume 1 Fundamental Laws Mechanics Electrodynamics Quantum Mechanics-A.S. Kompaneyets PDFRoberto Pomares100% (1)

- Bramann, Understanding The End of ArtDocument13 paginiBramann, Understanding The End of ArtJesús María Ortega TapiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Altermodern: A Conversation with Nicolas Bourriaud on the Tate Triennial conceptDocument3 paginiAltermodern: A Conversation with Nicolas Bourriaud on the Tate Triennial conceptchris_tinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Les Mardis de Stephane MallarmeDocument75 paginiLes Mardis de Stephane Mallarmeclausbaro2Încă nu există evaluări

- Arthur C. Danto "The Abuse of Beauty"Document23 paginiArthur C. Danto "The Abuse of Beauty"Yelena100% (6)

- Art, Kitsch, and the Modern PredicamentDocument7 paginiArt, Kitsch, and the Modern PredicamentShabari Choudhury100% (1)

- Why Art Became Ugly - Stephen HicksDocument6 paginiWhy Art Became Ugly - Stephen HicksMarcel AntonioÎncă nu există evaluări

- On the Social History of Art Explores Links Between Art and PoliticsDocument10 paginiOn the Social History of Art Explores Links Between Art and PoliticsNicole BrooksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Benjamin Buchloh - Allegorical Procedures: Appropriation and Montage in Contemporary ArtDocument15 paginiBenjamin Buchloh - Allegorical Procedures: Appropriation and Montage in Contemporary ArttigerpyjamasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summary Of "Art At The End Of The Century, Approaches To A Postmodern Aesthetics" By María Rosa Rossi: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESDe la EverandSummary Of "Art At The End Of The Century, Approaches To A Postmodern Aesthetics" By María Rosa Rossi: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art Relations and The Presence of AbsenceDocument13 paginiArt Relations and The Presence of AbsenceSantiago SierraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spencer-Brown - Probability PDFDocument164 paginiSpencer-Brown - Probability PDFJoaquin Rauh100% (1)

- Some Text On Odd NerdrumDocument6 paginiSome Text On Odd Nerdrumnergalu100% (1)

- Pic Writing ResearchDocument22 paginiPic Writing ResearchHutami DwijayantiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Partha Mitter - The Triumph of ModernismDocument273 paginiPartha Mitter - The Triumph of ModernismKiša Ereš100% (12)

- An Archeology of A Computer Screen Lev ManovichDocument25 paginiAn Archeology of A Computer Screen Lev ManovichAna ZarkovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nicholas Bourriaud - PostproductionDocument45 paginiNicholas Bourriaud - PostproductionElla Lewis-WilliamsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Color, Facture, Art and Design: Artistic Technique and the Precisions of Human PerceptionDe la EverandColor, Facture, Art and Design: Artistic Technique and the Precisions of Human PerceptionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Suzi Gablik Has Mondernism Failed?Document10 paginiSuzi Gablik Has Mondernism Failed?Romana PeharÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nature of Abstract Art ExploredDocument15 paginiNature of Abstract Art ExploredHamed HoseiniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bourriaud - Relational AestheticsDocument4 paginiBourriaud - Relational Aesthetics232323232323232323100% (2)

- Natasha Edmonson Kandinsky ThesisDocument44 paginiNatasha Edmonson Kandinsky ThesisJorge PezantesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Poetics of Installation ArtDocument53 paginiThe Poetics of Installation ArtMelissa ChemimÎncă nu există evaluări

- 41370602Document3 pagini41370602Omega ZeroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aesthetic Journalism: How to Inform Without InformingDe la EverandAesthetic Journalism: How to Inform Without InformingEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Field Notes on the Visual Arts: Seventy-Five Short EssaysDe la EverandField Notes on the Visual Arts: Seventy-Five Short EssaysÎncă nu există evaluări

- Constructivism QuotesDocument8 paginiConstructivism QuotesSam HarrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Angels' Wings: A Series Of Essays On Art And Its Relation To LifeDe la EverandAngels' Wings: A Series Of Essays On Art And Its Relation To LifeÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Doctor's Degree For Artists!Document19 paginiA Doctor's Degree For Artists!nicolajvandermeulenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bereaving BeautyDocument8 paginiBereaving BeautyLinda Saskia MenczelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gregory Battcock - Minimal ArtDocument7 paginiGregory Battcock - Minimal ArtLarissa CostaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Contemporary Art and The Not-Now: Branislav DimitrijevićDocument8 paginiContemporary Art and The Not-Now: Branislav DimitrijevićAleksandar BoškovićÎncă nu există evaluări

- Concerning The Spiritual in ArtDocument41 paginiConcerning The Spiritual in ArtJavier CebrianÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Visual Arts in What Art IsDocument3 paginiThe Visual Arts in What Art Israj100% (2)

- Art Lesson 3Document12 paginiArt Lesson 3James AguilarÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Relationshipbetween Art Scienceand TechnologyDocument13 paginiThe Relationshipbetween Art Scienceand TechnologyIrving Tapia PerezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Icolas Bourriaud Postproduction Culture As Screenplay: How Art Reprograms The WorldDocument47 paginiIcolas Bourriaud Postproduction Culture As Screenplay: How Art Reprograms The Worldartlover30Încă nu există evaluări

- Greenberg, Clement - Avant Garde and Kitsch (1939)Document5 paginiGreenberg, Clement - Avant Garde and Kitsch (1939)AAA b0TÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bourriaud Nicholas - Postproduction DraggedDocument15 paginiBourriaud Nicholas - Postproduction DraggedAluminé RossoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art, Design, Craft, Beauty and All Those Things…De la EverandArt, Design, Craft, Beauty and All Those Things…Încă nu există evaluări

- Oxford University Press The Musical Quarterly: This Content Downloaded From 132.248.9.8 On Mon, 16 Oct 2017 00:51:53 UTCDocument24 paginiOxford University Press The Musical Quarterly: This Content Downloaded From 132.248.9.8 On Mon, 16 Oct 2017 00:51:53 UTCNayeli Gutiérrez HernándezÎncă nu există evaluări

- This Content Downloaded From 193.225.246.20 On Wed, 10 Nov 2021 17:38:40 UTCDocument25 paginiThis Content Downloaded From 193.225.246.20 On Wed, 10 Nov 2021 17:38:40 UTCbagyula boglárkaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Readymades & the Creative ActDocument4 paginiReadymades & the Creative ActMeru SharmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conceptual Art: Fluke or FatalityDocument6 paginiConceptual Art: Fluke or FatalitySkyeFishÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chaps 1-2 REmedios, ARt AppreDocument24 paginiChaps 1-2 REmedios, ARt AppreArol Shervanne SarinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- PhilipPearlstein On Stylistic CensorshipDocument7 paginiPhilipPearlstein On Stylistic CensorshipFrank HobbsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bourriaud Nicolas - PostproductionDocument47 paginiBourriaud Nicolas - PostproductionEd ThompsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- BURNHAM, J. - Beyond - Modern - Sculpture. The Effects of Science and Technology On The Sculpure of This Century (Inglés)Document416 paginiBURNHAM, J. - Beyond - Modern - Sculpture. The Effects of Science and Technology On The Sculpure of This Century (Inglés)bodojig278Încă nu există evaluări

- Thomas Crow Unwritten Histories of Conceptual ArtDocument6 paginiThomas Crow Unwritten Histories of Conceptual Artarp_mÎncă nu există evaluări

- MCP413X/415X/423X/425X: 7/8-Bit Single/Dual SPI Digital POT With Volatile MemoryDocument82 paginiMCP413X/415X/423X/425X: 7/8-Bit Single/Dual SPI Digital POT With Volatile MemoryEyeVeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ciat Lonbarde FoursesDocument8 paginiCiat Lonbarde FoursesEyeVeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- What You Need To Know About Using General Purpose Op Amps at Low Voltage - Analog - Technical Articles - TI E2E Support ForumsDocument3 paginiWhat You Need To Know About Using General Purpose Op Amps at Low Voltage - Analog - Technical Articles - TI E2E Support ForumsEyeVeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparing High Speed ComparatorsDocument10 paginiComparing High Speed ComparatorsEyeVeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- EnvironmentalpsychologyDocument11 paginiEnvironmentalpsychologyEyeVeeÎncă nu există evaluări

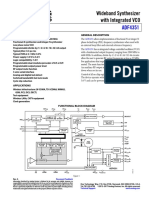

- Adf4351 PDFDocument28 paginiAdf4351 PDFEyeVeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Obsolete: Self-Contained Audio Preamplifier SSM2017Document8 paginiObsolete: Self-Contained Audio Preamplifier SSM2017EyeVeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Are Tvs DiodesDocument1 paginăWhat Are Tvs DiodesManu MathewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Home HTTPD Data Media-Data 7 GarageBand2 Getting Started PDFDocument77 paginiHome HTTPD Data Media-Data 7 GarageBand2 Getting Started PDFEyeVeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 Panel Cassette J Card TemplateDocument1 pagină3 Panel Cassette J Card TemplateEyeVeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mixxx Manual PDFDocument100 paginiMixxx Manual PDFdanielÎncă nu există evaluări

- UP NYC Performance Festival Preview - INCIDENT Magazine PDFDocument4 paginiUP NYC Performance Festival Preview - INCIDENT Magazine PDFEyeVeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Metawearc Cpro PsDocument20 paginiMetawearc Cpro PsEyeVeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Question Bank (Unit I) Cs6402-Design and Analysis of Algorithms Part - ADocument12 paginiQuestion Bank (Unit I) Cs6402-Design and Analysis of Algorithms Part - Aviju001Încă nu există evaluări

- Molecular Technique For Gender Identification: A Boon in Forensic OdontologyDocument12 paginiMolecular Technique For Gender Identification: A Boon in Forensic OdontologyBOHR International Journal of Current research in Dentistry (BIJCRID)Încă nu există evaluări

- P-3116 - Immunocytochemistry Lecture Notes PDFDocument26 paginiP-3116 - Immunocytochemistry Lecture Notes PDFSwetha RameshÎncă nu există evaluări

- BQS562 Cfaap2244b WBLFF AdliDocument7 paginiBQS562 Cfaap2244b WBLFF AdliWAN ADLI WAN SHARIFUDZILLAHÎncă nu există evaluări

- Utilizing sludge to produce strong bricksDocument7 paginiUtilizing sludge to produce strong bricksSagirul IslamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Risk Assessment of Jetty-Less LNG Transfer System For Onshore LNG TerminalDocument335 paginiRisk Assessment of Jetty-Less LNG Transfer System For Onshore LNG TerminalMuhammad AdlanieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Exemplar Art 6Document3 paginiLesson Exemplar Art 6Arranguez Albert ApawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 5Document41 paginiModule 5Ysabel TolentinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- IP UK Pine Needle Power Generation PDFDocument23 paginiIP UK Pine Needle Power Generation PDFSunny DuggalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cover Letter For Drilling Engineering PDFDocument1 paginăCover Letter For Drilling Engineering PDFHein Htet ZawÎncă nu există evaluări

- Twin Rotor MIMO System Documentation GuideDocument2 paginiTwin Rotor MIMO System Documentation GuideJaga deshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Calculation Methods For Lightning Impulse Voltage Distribution in Power TransformersDocument6 paginiCalculation Methods For Lightning Impulse Voltage Distribution in Power TransformersJoemon HenryÎncă nu există evaluări

- 18CEC304L Construction Engineering and Management LaboratoryDocument2 pagini18CEC304L Construction Engineering and Management LaboratorymekalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11.1 - Skill Acquisition: Assessment Statement Notes 11.1.1Document3 pagini11.1 - Skill Acquisition: Assessment Statement Notes 11.1.1Alamedin SabitÎncă nu există evaluări

- THC 6 Final Module 2Document142 paginiTHC 6 Final Module 2Arvie Tejada100% (1)

- Bay of BengalDocument18 paginiBay of BengalKarl GustavÎncă nu există evaluări

- Change The Way You PersuadeDocument19 paginiChange The Way You PersuadeGroundXero The Gaming LoungeÎncă nu există evaluări

- January 2016 QPDocument20 paginiJanuary 2016 QPSri Devi NagarjunaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beseler 67C EnlargerDocument4 paginiBeseler 67C EnlargerrfkjanÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5 SetDocument34 pagini5 SetQuynh NguyenÎncă nu există evaluări

- ITM Unit 2 - Tutorial Sheet - StudentsDocument4 paginiITM Unit 2 - Tutorial Sheet - StudentsalexÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topic: References: Materials: Value Focus: Lesson Plan in Health 6Document7 paginiTopic: References: Materials: Value Focus: Lesson Plan in Health 6Kathleen Rose ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1w5q Chapter 3 Dynamics of Linear MotionDocument2 pagini1w5q Chapter 3 Dynamics of Linear MotionKHOO YI XIAN MoeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Effective Management 7th Edition Chuck Williams Test BankDocument25 paginiEffective Management 7th Edition Chuck Williams Test BankJessicaMathewscoyq100% (55)

- Ways of CopingDocument5 paginiWays of Copingteena jobÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lec-19 Ethical Framework For Helath ResearchDocument17 paginiLec-19 Ethical Framework For Helath ResearchNishant KumarÎncă nu există evaluări