Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Principles of Gandhiji

Încărcat de

Aditya GulatiDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Principles of Gandhiji

Încărcat de

Aditya GulatiDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Gandhigiri for sustainable growth

Economic Times, September 30, 2010

Innovation at leading Indian companies suggests that inclusive growth

policies are beginning to have the desired effect in rural areas and

on the urban poor. But much more is required from the government and

industry.

In two days, we will celebrate the 141st birth anniversary of Mahatma

Gandhi. It is only appropriate that we consider how his life's core

principles relate to our own economic times.

Historian Ramachandra Guha has described Gandhi as the single most

important influence on the environmental movement in the country.

His assertion, "the Earth has enough for everyone's need, but not for

anyone's greed" has been repeatedly invoked by environmentalists. He

made an equally-prescient statement, "It took Britain half the

resources of the planet to achieve (their) prosperity.

How many planets will a country like India require?" These Gandhian

ideas go to the heart of concerns about the sustainability of economic

growth in the world in general, and India in particular.

We are now at a juncture on the road to growth where we face two choices.

The first is unconstrained economic growth that enables us to race

ahead to the future, but with significant downsides such as weakened

long-term economic security and well-being due to non-renewable

resource constraints, climate change and environmental damage.

The other path is sustainable growth, which is the use of

sustainability-based innovations to develop products and services,

business models and platforms, and infrastructure.

Sustainable Growth 1.0, 2.0, 3.0

In the June 2010 issue of Harvard Business Review, Prof C K Prahalad

made one of his last contributions to management thought by

introducing, with his co-author R A Mashelkar, the notion of Gandhian

innovation.

These are business innovations that embody two core principles that

Gandhi lived by: affordability and environmental sustainability.

We can add a third core principle in Gandhi's philosophy: freedom from

authoritarian control and a general distrust of the central authority.

Sustainable growth can be considered Gandhian growth because its

business innovations are rooted in these three principles.

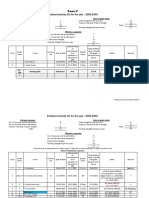

As illustrated below, the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s in India may be

described as Sustainable Growth 1.0. In this period, the easing of

many government controls led to business, technology and policy

innovations that initiated decentralised growth in the economy.

These changes, although partially implemented, illustrate the first

core Gandhian principle: decentralised control. The adoption of these

innovations then exploded in the next decade, 1995-2005, and resulted

in a boom in economic growth.

This decade also planted the seeds for innovation that initiated

inclusive growth by making products and services more affordable to

the vast majority of Indians.

In turn, Sustainable Growth 2.0's rapid expansion will likely be the

decade 2005-2015 in which we are halfway through, fuelled especially

by business innovations that target bottom of the pyramid. It,

therefore, illustrates the second core Gandhian principle,

affordability, and has now become the national agenda.

Our research of innovation at leading Indian companies - including

Hindustan Unilever, ITC, Larsen & Toubro, Novartis and Sanofi-Aventis

- suggests that inclusive growth is now rapidly reaching millions of

consumers in rural areas and the urban poor.

These innovations span consumer products, procurement, infrastructure

construction skills and healthcare, and use a variety of business

models to make them scaleable.

They may be considered as 'next-practices' platforms, because of their

ability to scale across markets and regions.

These companies are also well-positioned to extend their innovations

to Sustainable Growth 3.0, which may be described as eco-friendly

growth.

In this phase, innovations from previous phases get even more deeply

embedded in business practice, and also result in eco-friendly

innovations being deployed.

Leading companies such as Cadbury, Cosmos Ignite, Future Group,

Mahindra & Mahindra and Wipro are implementing next-practices platform

innovations that span sustainable farming, energy-efficient lighting

for the poor, consumer recycling through retail, eco-friendly

construction and transportation, and energy-efficient IT,

respectively.

These 10 companies are the tip of the eco-innovation iceberg, and

illustrate Gandhi's third core principle of environmental

sustainability.

It is encouraging that the government is finally putting together some

of the policy pieces required for accelerating Sustainable Growth 3.0.

These include measures such as the carbon tax on coal to fund clean

energy, the perform, achieve and trade (PAT) mandate for

energy-intensive facilities to reduce energy consumption, the National

Solar Mission to implement 20 gw of solar power by 2022 and several

other initiatives announced earlier this year. But the devil, as

always, is in the implementation of these policies.

There is much more that needs to be done. As Nandan Nilekani points

out in his book, Imagining India, sustainable growth will be more

effective when there is greater local control and clearer property

rights over local environmental and energy resources.

When it happens, it will represent a deepening linkage of the Gandhian

principles of decentralised controls and affordable access with that

of environmental sustainability. Sustainable Growth 3.0 is then likely

to escalate rapidly in mid-2010s to mid-2020s.

Drivers of successful change

Market demand is a greater driver of new behaviours than regulations,

especially if the latter are poorly enforced. For Sustainable Growth

3.0 to accelerate, eco-friendly growth needs to be viewed as a

business opportunity, rather than merely a reduction in risk from

non-compliance.

Sustainable Growth 2.0's lessons are instructive: inclusive growth

took off because companies realised it was a great opportunity to do

well financially by expanding markets while simultaneously doing good

to society.

There is another big driver of change that Gandhi used masterfully,

which proponents of Sustainable Growth 3.0 could do well to emulate.

It is the creation of an identity around the intended change that the

average Indian could easily relate to during the Independence

movements.

It represented a fearless Indian throwing off a colonial yoke and was

created through symbols such as the charkha and the lifting of sea

salt at Dandi, new words and phrases such as satyagraha and Quit

India, and by anchoring in values such as ahimsa that define our

heritage.

Perhaps we should take a leaf out of the Mahatma's notebook to locate

where to search for such an identity. He did not believe that,

traditionally, distinct spheres of life - such as economics, nature,

personal health and habits, and society - should be kept separate in

pursuing his work.

Instead, he sought to integrate them into his way of being and doing.

There is a sphere we have overlooked until now in this essay. It is

our own enduring Indian culture.

More precisely, it is our ancient worldview found in the Upanishads

relating humanity to nature, which transcends Hinduism itself and is

secular in its outlook. It was the foundation of the Mahatma's life

and guided his every action.

We can begin with an idea that the Mahatma considered a mahavakya

(great saying) in the Upanishads. It occurs in the very beginning of

the Isa Upanishad, Tena tyaktena bhunjitha.

It is the identity of a steward for this world, rather than an owner

who could do as he pleases with it. Its extended meaning, "renounce

ownership of the world and enjoy", embodied Gandhi's life.

Ultimately, sustainable growth is about growth through stewardship and

conservation of society, nature and its resources. This view has been

an integral part of our culture for over 3,000 years.

It is reflected in our innate thriftiness in everyday life, which

Gandhi again exemplified through the many stories of his frugality.

It is also evident in the numerous professions that make a living out

of recycling and reuse, such as the local kabadiwala on every street.

However, as our culture becomes more oriented to acquisition,

especially in a rapidly-growing economy, we risk letting go of these

habits that have served us well in the past.

There is another analogy we can draw from the Upanishads regarding

unconstrained and sustainable growth. In Katha Upanishad, the god of

death Yama tells the boy Nachiketas of the two paths that lie before

us: the path of pleasure (preyas) and the path of preference (sreyas).

The former is sweet initially but soon turns to poison. The latter is

like poison initially but then turns to nectar that provides sustained

joy.

Yama also compares this path to walking on the edge of a razor

(ksurasya dhara), but it gets easier as we progress on it.

This search for a greater path of conduct in life occurs throughout

the Upanishads. Sustainable growth is like this greater path:

difficult initially, but good for the world and good for the business

enterprises that stay with it.

The sages who composed the Upanishads over two millennia ago were

visionaries like Gandhi. We can learn something enduring from them,

and from this more recent Mahatma.

While many leading Indian companies are making a good start, we need

to build a broader base of support to scale these efforts throughout

Indian businesses and consumers.

By tapping into the sense of stewardship and conservation already

embedded in our national culture, we can build a national identity

around this greater path of sustainable growth.

Inclusive Growth Innovations

Pureit (Hindustan Unilever)

Consumer products for mass consumer

Range of products to enable safe drinking water by protecting from

water-borne diseases

e-Choupal (ITC)

Rural markets

Procurement services, rural distribution of goods and services,

financial services (insurance & credit) and rural retail stores

Construction skills training (Larsen & Toubro)

Underprivileged youth

Increase training and employability of youth in construction jobs

through training institutes

Arogya Parivar (Novartis)

Health services for the poor

Promote healthcare among the rural poor through direct education

Prayas (Sanofi-Aventis)

Health services for the poor

Promote healthcare among the rural poor by training medical practitioners

Eco-Friendly Innovations

Sustainable cocoa farming (Cadbury)

Coconut farmers

Use of cocoa as an intercrop between coconut or arecanut in

otherwise-unused land

The Great Exchange (Future Group)

Retail customers

Encourage customers to return unused items in several categories in

exchange for coupons

MightyLight (Cosmos Ignite)

Poor in rural and urban areas

Solar LED lighting and micro-energy for domestic use among the poor

Mahindra Reva (Mahindra & Mahindra)

Automotive customers

Electric vehicle technology, including electric drive train, through

majority stake in Reva

Wipro Green PC (Wipro)

Computing customers

RoHS-compliant, Energy Star rating 5, ranked #2 green electronics

brand globally by Greenpeace

Name of innovation (name of company), targeted market & innovation

description These are illustrative innovations considered in-depth by

the authors. Many of these companies have several innovations across a

variety of categories spanning both inclusive and eco-friendly growth

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Question Bank Sharira Kriya Rakta DhatuDocument89 paginiQuestion Bank Sharira Kriya Rakta DhatuMSKCÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2022 ECstudentsDocument2 pagini2022 ECstudentsDayanand GKÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review DPC Order - DTD - 10.09.10 of Inspector To Superintendent in Lucknow, Ghaziabad, Merrut, Allahabad, Noida & Kanpur Central Excise & Customs.Document13 paginiReview DPC Order - DTD - 10.09.10 of Inspector To Superintendent in Lucknow, Ghaziabad, Merrut, Allahabad, Noida & Kanpur Central Excise & Customs.SUSHIL KUMARÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grade 4 Lesson 1, 2& 3 Question Answer and MeaningsDocument5 paginiGrade 4 Lesson 1, 2& 3 Question Answer and Meaningsfathima sarahÎncă nu există evaluări

- ISKCON Desire Tree - Garam MasalaDocument1 paginăISKCON Desire Tree - Garam MasalaISKCON desire tree100% (1)

- Modern History TimelineDocument5 paginiModern History Timelinepushkar kumar100% (1)

- Sadhu Om Part 3 A Light On The Teaching of Ramana MaharshiDocument95 paginiSadhu Om Part 3 A Light On The Teaching of Ramana Maharshixear818Încă nu există evaluări

- Baby Boy NameDocument4 paginiBaby Boy Namevwake00Încă nu există evaluări

- IrctcstationsDocument196 paginiIrctcstationsmani8312Încă nu există evaluări

- Project Report PrefixDocument4 paginiProject Report Prefixapi-3848496Încă nu există evaluări

- Kormo Fol by Rabindranath TagoreDocument25 paginiKormo Fol by Rabindranath TagoreVertuial MojlishÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic AstrologyDocument37 paginiBasic AstrologyT. Manohar Rao100% (3)

- A Journey Through A New and Breathtaking World by Mohd Shafi SagarDocument10 paginiA Journey Through A New and Breathtaking World by Mohd Shafi SagarMohd ShafiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Who's Who GKDocument8 paginiWho's Who GKMousumi KayetÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Wings To AwakeningDocument401 paginiThe Wings To AwakeningAyurvashitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ae Aee PDFDocument173 paginiAe Aee PDFRushikesh Reddy DigaventiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heart of Hinduism: Key ConceptsDocument2 paginiHeart of Hinduism: Key ConceptstpspaceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Saurashtra (State)Document5 paginiSaurashtra (State)Pushpa B SridharanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nachiketa - Katha UpanishadDocument8 paginiNachiketa - Katha UpanishadAanal JethaliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Word Hijra Is An Urdu Word Meaning Eunuch or HermaphroditeDocument5 paginiThe Word Hijra Is An Urdu Word Meaning Eunuch or Hermaphroditesourabh singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

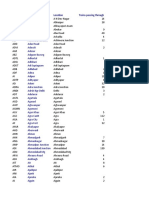

- Zone-V: Finalized Seniority List For The Year: 2002-2003Document12 paginiZone-V: Finalized Seniority List For The Year: 2002-2003rupaavath rajaanaikÎncă nu există evaluări

- WhosWho 2014-15 PDFDocument136 paginiWhosWho 2014-15 PDFvaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- VEDIC RULES of Temples ConstructionDocument2 paginiVEDIC RULES of Temples ConstructionGopu Rajesh KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jaimal Singh - Spiritual LettersDocument215 paginiJaimal Singh - Spiritual Lettersjaswaniji94% (32)

- 2gi19at002 ADocument51 pagini2gi19at002 AAaditya AttigeriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acma It Show 2009Document4 paginiAcma It Show 2009sharvikyagnikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sri Venkateshwara Divya Maha Mantra Likhitha JapaDocument28 paginiSri Venkateshwara Divya Maha Mantra Likhitha JapaTrajasekara TirupathiÎncă nu există evaluări

- B. Com-TYDocument21 paginiB. Com-TYNehaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Class 7 His The Delhi Sultanate 1630945304Document6 paginiClass 7 His The Delhi Sultanate 1630945304Darshan PadmapriyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cs Flaw LLB Sem6Document28 paginiCs Flaw LLB Sem6Akash NarayanÎncă nu există evaluări