Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies 2016 Handbook of The Psy

Încărcat de

ydtrgnTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies 2016 Handbook of The Psy

Încărcat de

ydtrgnDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

C H A P T E R

21

Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies

for Late-Life Mood and Anxiety

Disorders

Lisa C. Barry1 and Amy L. Byers2

1

University of Connecticut Health Center, Center on Aging, Farmington, CT, USA 2University

of California, San Francisco, CA, USA and San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center,

San Francisco, CA, USA

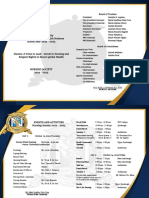

O U T L I N E

Introduction 410 Late-Life Anxiety Disorders 416

Epidemiology of Late-Life Anxiety Disorders 416

Late-Life Depression 410

Risk Factors for Late-Life Anxiety Disorders 416

Epidemiology of Late-Life Depression 410

Sociodemographic Risk Factors for Late-Life Co-Existing Mood and Anxiety

Depression 411 Disorders 417

Sex 411 Epidemiology of Late-Life Co-existing

Race 411 Mood–Anxiety Disorders 417

Biological and Clinical Risk Factors for Characteristics of Co-existing

Depression 412 Mood–Anxiety Disorders 417

The Inter-relationship Between

Risk Factors for Late-Life Suicide and

Cardiovascular Disease, Dementia, and

Suicidal Behavior 417

Depression 412

Disability 413 Detection, Treatment, and Management 419

Psychosocial Risk Factors for Depression 414

Conclusion 420

Social Support 414

Bereavement 415 References 421

K.W. Schaie & S.L. Willis (Eds) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-411469-2.00021-2

Handbook of the Psychology of Aging, Eighth edition. 409 © 2016

2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

410 21. RISK FACTORS FOR MOOD AND ANXIETY DISORDERS

INTRODUCTION LATE-LIFE DEPRESSION

Mood disorders, as specified in the Epidemiology of Late-Life Depression

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

The first portion of this chapter will largely

Disorders—Fourth (DSM-IV) or Fifth Edition

focus on late-life depression. Major depres-

(DSM-V), include major depressive disorder,

sion is a common feature of late-life bipolar

dysthymia (i.e., persistent depression), and

disorder. Furthermore, findings from brain

bipolar I and II disorder. These disorders are

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies con-

rare in older persons, with 3.6% of persons

sistently indicate that white matter hyperinten-

age 65–74 years, and approximately 2% of old-

sity (WMH) burden, a marker of white matter

old (75–84 years) and oldest-old (≥85 years)

disease, is high in older persons with major

persons, experiencing any mood disorders

depressive disorder or bipolar disorder indi-

(DSM-IV) within a 12-month period (Byers et al.,

cating similar psychopathology. Similarly, risk

2010). Of the mood disorders, the prevalence

factors, treatment, and prevention for major

of either bipolar I or II among older persons is

depression, dysthymia, and subsyndromal

particularly low, with prevalence estimates of

depression are non-distinguishable.

0.5–1.0% (Byers et al., 2010; Kessler, Berglund

Large-scale epidemiologic studies indicate

et al., 2005; Unutzer, Simon, Pabiniak, Bond, &

that the prevalence of major depressive dis-

Katon, 1998). In contrast, subsyndromal depres-

order among community-living samples of

sion, the presence of depressive symptoms that

adults age 65 and older is approximately 1–5%,

do not meet DSM criteria for major depression,

with the majority of studies reporting preva-

is more common with prevalence estimates

lence between 1% and 2% (Blazer, 2003; Hasin,

among community-living persons age 65 and

Goodwin, Stinson, & Grant, 2005). Of those

older ranging from 8% to 30% (Blazer, 2003;

older adults with major depression, some evi-

Forlani et al., 2014). Anxiety disorders includ-

dence indicates that approximately half are

ing panic disorder, agoraphobia without panic,

experiencing their first onset of depression in

specific phobia, social phobia, generalized anxi-

late life (i.e., late-onset depression) (Brodaty

ety disorder (GAD), and posttraumatic stress

et al., 2001; Bruce et al., 2002). However, because

disorder (PTSD), are also frequently experienced

by older persons, with a 12-month prevalence most studies of depression in later life do not

distinguish early versus late onset, it is difficult

estimate of 8.9% among those age 65–74 years,

to provide accurate estimates. General consensus

6.0% in those 75–84 years, and 8.1% in the old-

indicates that those with early-onset depression

est old (Byers et al., 2010). As will be further

are more likely to have a genetic predisposition

discussed, late-life mood and anxiety disorders

to depression or a personality disorder (Brodaty

have similar risk factors, overlapping symptom

et al., 2001). Yet, as will be discussed, identifica-

profiles, and frequently co-occur. These disor-

tion of genes that may be particularly impor-

ders are also often difficult to disentangle from

tant in the development of late-life depression

other conditions that affect the elderly, making

has focused on those associated with vascu-

diagnosis and treatment challenging. However,

lar disease. In contrast, the percentage of older

given that persons with mental illness are living

persons with clinically significant depressive

longer and that the incidence of late-onset mood

symptoms is high. Clinically significant depres-

and anxiety disorders is expected to increase

sive symptoms are depressive symptoms that

with the rapid aging of the population, the prev-

do not meet the criteria for major depression yet

alence of older persons with these disorders is

are considered clinically important given their

expected to increase.

IV. COMPLEX PROCESSES

Late-Life Depression 411

association with functional impairment (Blazer, older women than men (Barry, Allore, Guo,

2003; Hybels, Blazer, & Pieper, 2001; Lyness, Bruce, & Gill, 2008; Beekman, Copeland, &

King, Cox, Yoediono, & Caine, 1999; Lyness Prince, 1999; Sonnenberg, Beekman, Deeg, &

et al., 2007). Often referred to as depressed mood, van Tilburg, 2000), with this marked gender dif-

subsyndromal depression, or simply “depres- ference remaining throughout old age and only

sion,” clinically significant depressive symptoms narrowing among the oldest old (Djernes, 2006).

affect between 8% and 30% of older persons The prevalence of depression is not only higher

living in the community (Blazer, 2003; Forlani among older women, but women are also more

et al., 2014), with 25–49% experiencing persis- likely to have more severe depressive symptoms

tent symptoms (Barry, Abou, Simen, & Gill, (Shanmugasegaram, Russell, Kovacs, Stewart, &

2012; Mackenzie, El-Gabalawy, Chou, & Sareen, Grace, 2012). Reasons for the preponderance

2014; Sneed, Rindskopf, Steffens, Krishnan, & of depression in older women do not appear

Roose, 2008). Among older persons, white males to be an artifact of greater symptom reporting

age 85 years and older have been reported as among women. Rather, this sex difference has

having the highest prevalence of clinically sig- been attributed to women’s greater likelihood of

nificant depressive symptoms (18.9%) (U.S. having been exposed to risk factors for depres-

Census Bureau, 65+ in the United States; U.S. sion including lower income and having one or

Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, more chronic illnesses (Sonnenberg et al., 2000),

2014). and women’s higher likelihood of experiencing

Depression in older adults is a significant depression onset and persistence of depressive

public health concern because it is associ- symptoms (Barry et al., 2008). One study also

ated with adverse outcomes across its broad reported that, once depressed, women have a

spectrum. Older adults with depression, from lower likelihood of dying as compared with

major depression to subsyndromal depres- men (Barry et al., 2008). Whereas older men

sion, are more likely to experience increased generally have higher mortality rates than older

health care costs (Katon, Lin, Russo, & Unutzer, women, irrespective of depression, the find-

2003), exacerbation of co-existing medical ill- ings from this aforementioned study showed

ness (Carnethon et al., 2007), onset of disabil- a nearly threefold difference in the odds ratios

ity in activities of daily living (ADLs; Barry, for participants who were depressed compared

Allore, Bruce, & Gill, 2009; Barry, Murphy, & with those who were not depressed. Women

Gill, 2011; Penninx, Leveille, Ferrucci, Van Eijk, who were depressed were 75% less likely to die

& Guralnik, 1999), and mortality (Penninx, as compared with men who were depressed.

Geerlings, et al., 1999; Unutzer, Patrick, In contrast, among the non-depressed, women

Marmon, Simon, & Katon, 2002). Furthermore, were 20% less likely to die than men.

both risk and protective factors are similar for

major depressive disorder and clinically signifi- Race

cant depressive symptoms. Persons age ≥65 years in the United States

are predominantly white but are becoming

increasingly diverse. Whereas minority popu-

Sociodemographic Risk Factors for lations comprised approximately 20% of older

Depression adults in 2010, projections indicate that by 2050

the composition of the older population will be

Sex 58% non-Hispanic White, 20% Hispanic, 12%

It is well-established that the burden of Black, and 9% Asian (“Older Americans 2012:

depression is disproportionately higher among Key Indicators of Well-Being,” 2012).

IV. COMPLEX PROCESSES

412 21. RISK FACTORS FOR MOOD AND ANXIETY DISORDERS

Despite growing numbers of minorities liv- depression onset or an increase in depres-

ing to older ages, whether or not race is a risk sive symptoms. Among those with depressive

factor for mood disorders in later life is uncer- symptoms, the lower rate of increase over time

tain. The majority of studies focusing on race for minorities as compared with Whites, par-

differences in mood disorders in later life have ticularly among Hispanics, may be explained

evaluated Black–White differences in depres- by minority persons’ effective use of coping

sion. However, how depression is defined strategies in old age that they learned through-

across studies contributes to the uncertainty out life to deal with racial discrimination

regarding the role of Black–White race in late- (Ferraro & Farmer, 1996).

life depression. Whereas the 12-month preva-

lence of major depression has been reported

to be similar among older Whites and Blacks Biological and Clinical Risk Factors for

(Byers et al., 2010), some studies report that Depression

Blacks are more likely to experience clinically

significant depressive symptoms, even after The Inter-relationship Between

controlling for factors such as socioeconomic Cardiovascular Disease, Dementia, and

status (SES) (Barry et al., 2014; Jang, Borenstein, Depression

Chiriboga, & Mortimer, 2005). In the United Older adults with depression have an

States, SES and race are inextricably related, increased risk of developing cardiovascular

with Blacks having markedly fewer socioeco- disease and dementia. In fact, evidence that

nomic resources than Whites (LaVeist, 2005). vascular disease is the underlying link between

Consequently, controlling for SES is particularly depression and dementia is strong (Byers &

important in studies evaluating race differences Yaffe, 2011). This link is largely grounded in the

in health outcomes. Other studies report the “vascular depression hypothesis” (Alexopoulos

opposite or have found no association (Cohen, et al., 1997; Krishnan, Hays, & Blazer, 1997),

Magai, Yaffee, & Walcott-Brown, 2005; Gallo, which states that cerebrovascular disease pre-

Cooper-Patrick, & Lesikar, 1998). Longitudinal disposes to, precipitates or perpetuates some

studies evaluating race differences in trajecto- geriatric depressive syndromes (Alexopoulos,

ries of depression symptoms indicate that as 2003, 2005). Although it has been suggested

compared with older Whites, older Blacks are that vascular lesions and structural changes in

more likely to experience an increase in depres- the brain lead to depression in late life (Camus,

sive symptoms (Skarupski et al., 2005) and an Kraehenbuhl, Preisig, Bula, & Waeber, 2004;

increase in depression onset (Barry et al., 2014) De Groot et al., 2000; Thomas, Perry, Barber,

over time. However, findings from the Health Kalaria, & O’Brien, 2002), the direction of such

and Retirement Study (HRS) and its companion an association is debatable, as vascular disease

study, the Asset and Health Dynamics among or vascular lesions and depression are related

the Oldest Old (AHEAD), indicate that the rate to an increased risk of developing the other

of change in depressive symptoms over time is (Thomas, Kalaria, & O’Brien, 2004).

lower for older Blacks and Hispanics as com- The pathway that explains the inter-rela-

pared with older Whites (Xiao, Liang, Bennett, tionship between vascular disease, depression,

Quinones, & Wen, 2010). Because older Blacks, and dementia is probably not sequential. Prior

more so than Whites, live in areas with lower- depression is related to subsequent vascular dis-

quality healthcare, neighborhood character- ease through multiple proposed mechanisms,

istics may contribute to older Blacks’ (Beard including behavioral conditions (e.g., smoking,

et al., 2009) higher likelihood of experiencing inactivity),hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal(HPA)

IV. COMPLEX PROCESSES

Late-Life Depression 413

axis dysregulation and elevated cortisol related nerve growth factors, and increased deposi-

to the metabolic syndrome, disruption of nor- tion of amyloid-β plaques (Byers & Yaffe, 2011).

mal endothelial function and development of In particular, amyloid-associated depression,

hypertension, and pro-inflammatory cytokines defined as the presence of clinical symptoms of

(Butters et al., 2008). As evidence, depression depression and a high plasma Aβ40:Aβ42 ratio,

has been found to increase risk of first-ever may define a subtype of depression represent-

myocardial infarction and stroke (Liebetrau, ing a prodromal manifestation of Alzheimer

Steen, & Skoog, 2008). On the other hand, evi- disease given its strong association with

dence that vascular disease promotes devel- memory impairment (Sun et al., 2008). Recent

opment of depression is well established. For findings from the Health Aging and Body

example, risk of depression is substantially Composition (Health ABC) Study have also

increased post-MI and post-stroke (Thomas found that older persons with a high Aβ40:Aβ42

et al., 2004). In addition, MRI studies have sup- ratio who also have an APOE e4 allele may be

ported robust associations between ischemic at increased risk for incident depression (Metti

brain lesions and depression or depressive et al., 2013).

symptoms in older adults (Herrmann, Le In summary, although research supports an

Masurier, & Ebmeier, 2008; Steffens, Krishnan, association between late-life depression and

Crump, & Burke, 2002). Longitudinal stud- risk of dementia, inconsistencies across indi-

ies provide evidence that large cortical lesions vidual studies exist. Because of the timing of

and severe subcortical white matter grade are many of these studies in late life, they cannot

significant risk factors for developing depres- distinguish whether depression or depressive

sive symptoms (Steffens et al., 2002); with symptoms are a prodromal phase of dementia

these changes predating and predicting late-life or consequence of the onset of AD or are a risk

depression (Steffens et al., 2002; Teodorczuk factor. In fact, the variability of the duration of

et al., 2007). follow-up (e.g., 0–17 years) and unknown fre-

The “vascular–depression–dementia hypoth- quency or duration of depressive episodes may

esis,” is further supported by evidence that explain the heterogeneity of findings. In con-

vascular disease contributes to the clinical trast, earlier-life depression (typically defined

manifestation of dementia symptoms (Flicker, as depression or depressive symptoms occur-

2008, 2010). Ischemic damage, largely in the ring before age 60) consistently has been found

frontostriatal brain regions, may lead to sig- to be a risk factor for (and unlikely prodrome

nificant cognitive deficits (Alexopoulos, 2006). of) dementia (Jang et al., 2005). However, more

Finally, the ischemic damage to frontostriatal longitudinal studies over the lifespan are nec-

brain regions may explain the executive func- essary in order to fully understand the rela-

tion deficits and psychomotor slowing that are tionship between depression and depressive

common in late-life depression (Bruce et al., symptoms and risk of developing dementia in

2002; Butters et al., 2008; Sheline et al., 2008). late life.

This suggests that ischemic structural changes

in the brain are a common etiologic factor of Disability

both the depression and the related cognitive A large body of literature has evaluated the

impairment. association between disability in ADLs (e.g.,

Other likely biological mechanisms linking bathing, walking, dressing, transferring) and

depression to dementia include alterations in depression in older persons, with general con-

glucocorticoid steroid levels and hippocam- sensus that these conditions are inextricably

pal atrophy, inflammatory changes, deficits of linked. However, some research points to a

IV. COMPLEX PROCESSES

414 21. RISK FACTORS FOR MOOD AND ANXIETY DISORDERS

stronger influence of disability on subsequent a lower likelihood of recovering from disability

depression than that of depression on disabil- (Barry et al., 2011).

ity (Chen et al., 2012; Ormel, Rijsdijk, Sullivan,

van Sonderen, & Kempen, 2002). Stress theory Psychosocial Risk Factors for Depression

(Avison & Turner, 1988; Pearlin, Lieberman,

Menaghan, & Mullan, 1981) asserts that new Social Support

disability or the ongoing psychological and What is now a vast literature detailing the

physical stress of chronic disability alters home- influence of social support on health was

ostasis, thereby leading to depression. In turn, spurned by Cassel (1976) and Cobb (1976), epi-

depression may alter neural, hormonal, or demiologists who suggested that investigation

immunological function, subsequently result- of this relationship was critical. Whereas earlier

ing in disability. Whereas many cross-sectional studies had described a link between sociali-

studies and studies with one follow-up period zation and depression (Paykel, Weissman,

have found a relationship between disability Prusoff, & Tonks, 1971; Paykel & Weissman,

and depression in older persons (Bruce, 2001; 1973), it was nearly two decades after the

Harris, Cook, Victor, DeWilde, & Beighton, publication of the Cassel and Cobb studies

2006; Ormel et al., 2002), findings from large that research began to accumulate regard-

prospective cohort studies have contributed ing the impact of social support on the mental

significantly to our understanding of this rela- health of older persons. Early findings from

tionship. The Precipitating Events Project (PEP) the New Haven Established Populations for

(Gill, Desai, Gahbauer, Holford, & Williams, Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly (EPESE)

2001), an ongoing prospective cohort study of indicated that the perceptions that one has

754 nondisabled members of a large health plan adequate emotional support and available

who were 70 years of age or older at study ini- instrumental support each were indepen-

tiation in 1998, includes monthly self-reported dently associated with fewer depressive symp-

assessments of ADL disability and assessments toms in older persons (Oxman, Berkman, Kasl,

of depressive symptoms every 18 months. Freeman, & Barrett, 1992), with emotional sup-

Findings from PEP have shown that not only port characterized by the amount of “love and

is disability a salient risk factor for depression, caring, sympathy and understanding, and/or

but also that the burden of disability influ- esteem or value available from others” (Thoits,

ences this relationship. Barry, Soulos, Murphy, 1995) and instrumental support referring to

Kasl, and Gill (2013) found that PEP partici- “help, aid, or assistance with tangible needs

pants’ odds of experiencing clinically signifi- such as getting groceries, getting to appoint-

cant depressive symptoms, as assessed using ments, phoning, cooking, cleaning, or paying

the 11-item Centers for Epidemiologic Studies- bills” (Berkman & Kawachi, 2000). To date, a

Depression Scale (Kohout, Berkman, Evans, & large number of studies have evaluated the

Cornoni-Huntley, 1993), increased as the sever- association between social support and depres-

ity of their disability increased, with particu- sion in older persons and have expanded the

larly high odds of depression among those with research to numerous related concepts includ-

both chronic and severe disability as compared ing social network, social integration/connect-

with those with no disability (OR = 2.42; 95%CI edness, and social participation (Schwarzbach,

1.78–3.30). These researchers also found that Luppa, Forstmeier, Konig, & Riedel-Heller,

depression in older persons is not only associ- 2014). Generally, qualitative aspects of social

ated with disability onset, but it is also associ- support (e.g., perceived emotional support;

ated with worsening severity of disability and quality of relationships) seem to have a greater

IV. COMPLEX PROCESSES

Late-Life Depression 415

impact on depression in late life than quantita- association between bereavement and depres-

tive aspects (e.g., number of members in one’s sion among emerging cohorts of older persons.

social network). Furthermore, not all social Whether or not bereavement leads to nega-

support has a positive effect on depression. tive mental health outcomes in older persons

The perception of social support as excessive may also depend, in part, on the availability

or unhelpful, often in regard to instrumen- of social support and the context in which it

tal support, has been found to be associated occurs. Frequency of social contact has been

with increased depressive symptoms in older found to be associated with better psycho-

persons (Nagumey, Reich, & Newsom, 2004). logical health among widowed older persons

Increased resentment as one’s independence (Beckman, 1981; Silverstein & Bengtson, 1994).

is compromised may increase the likelihood of However, more recent data from 209 widowed

experiencing depression, despite the intentions persons who were participants in the Changing

of the one providing the support. Lives of Older Couples (CLOC) study indicate

that the amount of social contact is not associ-

Bereavement ated with depressive symptoms once degree of

Whereas bereavement is a normal response emotional support and the agreement between

to death accompanied by acute grief symp- the widowed person’s preferred and actual

toms that typically attenuate over time, it is a levels of social contact have been taken into

severe stressor that can precipitate a mental consideration (Ha & Ingersoll-Dayton, 2011).

health disorder. Prior studies have found an These latter findings indicate that the emo-

association between bereavement and major tional meaningfulness of social relationships

depressive disorder, with a meta-analysis of may matter more to older persons’ psychologi-

prospective studies indicating that the risk cal health than the amount of actual contact.

of experiencing depression in those age 50 Relatedly, negative social relationships may

and older was more than threefold among the also be associated with psychological health

bereaved (Cole & Dendukuri, 2003). However, among older widowed persons. For example,

while this risk is high, bereavement still con- results from one study that focused on changes

fers a lower risk of depression in older persons in positive and negative support from the chil-

as compared with younger and middle-aged dren of widowed older persons indicated that

adults. In terms of spousal death, which is com- negative support was associated with increased

mon in older age, the risk difference between anxiety and a decrease in positive support was

younger and older persons is largely attributed associated with increased depressive symptoms

to the greater expectedness of a spouse’s death (Ha, 2010).

in late life as compared with early or midlife While bereavement may be associated with

(Blazer & Hybels, 2005). Earlier studies indi- depression, whether other more severe and

cate that spousal bereavement has more nega- chronic forms of grief can be distinguished

tive psychological effects on men. Following clinically from bereavement-related depres-

the death of a spouse, men are more likely to sion has been debated for more than two dec-

become depressed and to be depressed longer. ades (Prigerson et al., 1995). In fact, there was

This gender difference has been attributed to significant debate regarding whether or not

older men’s unfamiliar household management complicated grief and/or prolonged grief dis-

roles (Umberson, Wortman, & Kessler, 1992). order (PGD) should be included in DSM-V

As traditional societal gender roles continue (Lichtenthal, Cruess, & Prigerson, 2004;

to diminish, it will be interesting to determine Prigerson et al., 2009; Shear et al., 2011). Given

whether gender will continue to influence the that no consensus was reached regarding their

IV. COMPLEX PROCESSES

416 21. RISK FACTORS FOR MOOD AND ANXIETY DISORDERS

inclusion, the “bereavement exclusion” was anxiety disorders were the most prevalent dis-

removed from the clinical criteria of depression orders among those aged 65 years and older

and adjustment disorders (Wakefield & First, in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Survey

2012). However, removal of that exclusion is (5.5%) with phobic disorder the most prevalent

also controversial mainly due to a worry that individual disorder (4.8%) (Hybels & Blazer,

grief will become “medicalized” and grieving 2003). In contrast, the Longitudinal Aging

individuals may be inappropriately prescribed Study Amsterdam determined high rates of

antidepressant medications. Consequently, GAD (7.3% vs. 2.0% in the NCS-R) (Beekman

“persistent complex bereavement disorder” is et al., 1998). This discrepancy between reported

included in the DSM-V in a chapter on condi- prevalence rates highlights largely methodolog-

tions needing further study. ical differences (e.g., sampling procedures and

attrition rates, definition and operationalization

of anxiety) and potential cultural differences

LATE-LIFE ANXIETY DISORDERS between population-based studies.

Epidemiology of Late-Life Anxiety Risk Factors for Late-Life Anxiety

Disorders Disorders

Although most information on late-life men- Despite the high prevalence of anxiety dis-

tal health disorders has focused on mood disor- orders in late life, risk factors associated with

ders, particularly major depressive disorder, the late-life anxiety have not been well studied or

occurrence of anxiety disorders has been found conceptualized. The limited research suggests

to be as high or even higher. Nationally repre- that risk factors for anxiety are similar to those

sentative 12-month prevalence estimates from for depression. This is not surprising given the

the National Comorbidity Survey Replication strong overlap between anxiety and depres-

(NCS-R) determined that nearly 12% of older sion seen throughout adult life and in late life

adults aged 55 years and older had any anxiety (as described below). First, shared genetic risk

disorder compared with 5% having any mood has been found between GAD and depression

disorder (Byers et al., 2010). In younger adults (Kendler, Gardner, Gatz, & Pedersen, 2007).

(18–44 years), the 12-month prevalence of any Secondly, research from the NCS-R has shown

anxiety disorder was markedly higher (20.7%) that anxiety disorders throughout the lifes-

than for older adults (Gum, King-Kallimanis, pan are associated with female gender, higher

& Kohn, 2009). When stratified by young-old number of comorbid chronic medical condi-

(55–64 years), mid-old (65–74 years), old-old tions, being unmarried or divorced, and having

(75–84 years), and oldest-old (≥85 years) US less than a high school education (Gum et al.,

respondents, the prevalence was 16.6%, 8.9%, 2009). Furthermore, research suggests that cog-

6.0%, and 8.1%, respectively, for any anxiety nitive impairment and dementia may be major

disorder (Byers et al., 2010). In comparison, for risk factors for anxiety in late life (Seignourel,

any mood disorder, it was 7.6%, 3.6%, 1.8%, Kunik, Snow, Wilson, & Stanley, 2008); how-

and 2.4%, respectively. ever, the overlap of symptomatology between

Among the NCS-R adults aged 55 years and anxiety and dementia complicates assessing the

older, the most prevalent anxiety disorder was association. In addition, older adults with vas-

specific phobia (6.5%), followed by social pho- cular dementia have been found to have higher

bia (3.5%), PTSD (2.1%), GAD (2.0%), panic dis- prevalence of anxiety than older adults with

order (1.3%), and agoraphobia (0.8%). Similarly, Alzheimer’s-type dementia (Seignourel et al.,

IV. COMPLEX PROCESSES

Risk Factors for Late-Life Suicide and Suicidal Behavior 417

2008), which suggests that anxiety in dementia meet criteria for GAD, often only during the

may be related to the vascular risk for depres- depressive episodes, the presence of GAD in

sion in late life. a major depressive episode should be consid-

ered a severity marker rather than as a separate

diagnosis. Supporting this line of reasoning, one

study found that in older adults with depressive

LATE-LIFE CO-EXISTING MOOD disorders, greater severity of depressive symp-

AND ANXIETY DISORDERS toms was associated with greater likelihood of

GAD symptoms including poorer social func-

Epidemiology of Late-Life Co-existing tion and high levels of somatic symptoms (such

Mood–Anxiety Disorders as sweating, nausea, and palpitations). However,

Most US studies of co-existing mood and this study also found that symptoms of GAD

anxiety disorders have been clinically based were independently associated with greater

and found high prevalence of comorbid anxiety suicidality, even after controlling for severity of

in patients with depression (Lenze, 2003; Lenze depressive symptoms (Lenze et al., 2000).

et al., 2000, 2001). Twenty-three percent of older

subjects (aged 60 years and older) with depres-

sive disorders had a current anxiety disorder RISK FACTORS FOR LATE-LIFE

diagnosis (Lenze et al., 2000). The most com- SUICIDE AND SUICIDAL

mon current co-existing anxiety disorders were BEHAVIOR

panic disorder (9.3%), specific phobia (8.8%),

and social phobia (6.6%). Interestingly, 27.5% Older adults who are living in the commu-

of older subjects with depression had symp- nity have suicide rates comparable to or higher

toms that met criteria for GAD. The prevalence than any other age group (Conwell, Duberstein,

went up to 45% GAD symptoms for those in & Caine, 2002), accounting for approximately

the inpatient psychiatric subgroup. In con- 15% of deaths by suicide in the United States

trast, nationally representative estimates from (“Medicare Improvements for Patients and

population-based research in NCS-R respond- Providers Act”). Older white men are at par-

ents documented that the 12-month prevalence ticularly high risk. Whereas older adults are less

of any co-existing mood and anxiety disorder likely than younger adults to engage in suicidal

was 3% among adults aged 55 years and older behavior which includes suicidal ideation (i.e.,

(Byers et al., 2010). thoughts, plans, or wishes to die or kill oneself)

or overt actions such as a suicide attempt, older

adults have a much higher likelihood of dying

when they make a suicide attempt. For every

Characteristics of Co-existing

completed suicide among older adults, an esti-

Mood–Anxiety Disorders mated 2–4 attempts occur (McIntosh, Santos,

Co-existing mood and anxiety disorders in Hubbard, & Overholser, 1994), while in younger

late life appear to be largely delineated by the adults the ratio of completed suicide to attempts

severity of somatic symptoms related to the may be as high as 200–1 (Fremouw, dePerczel,

mood or anxiety disorder, a decline in func- & Ellis, 1990). This difference has been attrib-

tion, or a particularly high accumulation of uted to older adults’ higher likelihood of using

individual risk factors for mood or anxiety. methods that are likely to result in a fatality,

Consequently, there is growing support for the such as firearms; 67% of suicides among older

view that because many depressed individuals adults occur via firearms.

IV. COMPLEX PROCESSES

418 21. RISK FACTORS FOR MOOD AND ANXIETY DISORDERS

Depression and prior suicide attempts are symptoms, which are considered the major

well-established risk factors for suicide that are risk factors for such behavior. Whereas indi-

shared by all age groups (National Institute vidual anxiety disorders have not been well

of Mental Health, 2015). As compared with established as risk factors for suicide in older

younger persons, however, suicide rates in persons, there is some evidence indicating

older persons are more closely associated with that anxiety disorders are associated with sui-

major depression. Depression is the most com- cidal behavior in this population. Lenze et al.

mon psychiatric diagnosis in older persons (2000) found that symptoms of GAD were

who died by suicide (Conwell, Van Orden, & associated with greater likelihood of suicidal

Caine, 2011), and both population-based stud- ideation above and beyond depressive sever-

ies and psychological autopsy studies among ity and other comorbid anxiety disorders in

persons who have died by suicide have found older adults with depressive disorders. In

that the association between suicidal ideation a population-based study of older primary

and depression is significantly stronger in older care patients from Australia, respondents

persons than in younger persons (Dennis et al., with anxiety, defined by using clinically sig-

2007; Gaynes et al., 2004). nificant cutoff scores based on the Hospital

Older persons also have a distinct risk pro- Anxiety and Depression Scale, were nine

file for suicide. Research has shown that 45% times more likely to have suicidal ideation

of older adults who die by suicide have seen a than those without anxiety (95% confidence

primary care provider within a month before interval (CI): 7.3–10.5). The association was

their suicide (Luoma, Martin, & Pearson, 2002). 11-fold increased odds for those with depres-

Comorbid chronic medical illness, particularly sion (95%CI: 8.7–14.3), and went up to 29-fold

that which results in inpatient hospitalization or increased odds of suicidal ideation for those

need for home care, pain, loss of independence with comorbid anxiety–depression (95%CI:

resulting from disability in ADLs such as bath- 23.9–36.0) (Almeida et al., 2012). Relatedly,

ing and dressing, loss of control over choices although PTSD has been established as a risk

regarding one’s health, and reduced sense of factor for completed suicide in younger vet-

purpose are risk factors for suicide in older erans (Pompili et al., 2013; Sher, Braquehaid,

persons (Conwell et al., 2002, 2010; Juurlink, & Casas, 2012), little is known about the asso-

Herrmann, Szalai, Kopp, & Redelmeier, 2004). ciation between PTSD and suicide risk in

In addition, lack of social connectedness (e.g., older adults. Studies of younger veterans have

social isolation, low social support) is an impor- shown that PTSD is highly associated with

tant risk factor for suicide among older adults suicide and suicidal behavior (Brenner et al.,

which, in turn, may also make them less likely 2011; Pompili et al., 2013). In addition, PTSD,

to be rescued after an attempt (Conner, Conwell, agoraphobia, GAD, panic disorder, social anxi-

& Duberstein, 2001). Emerging research areas ety disorder, and specific phobia have been

regarding risk factors for suicide in older persons documented in nationally representative stud-

include impulsivity in the context of cognitive ies of younger adults as risk factors for sui-

impairment (Dombrovski et al., 2008; Erlangsen, cidal behavior (Thibodeau, Welch, Sareen, &

Zarit, & Conwell, 2008) and change in living situ- Asmundson, 2013). However, research is con-

ation, such as a move to a long-term care facility troversial in this area, and almost nothing is

(Mezuk, Rock, Lohman, & Choi, 2014). known about the impact of individual anxiety

Suicidal behavior, like suicide, is highly disorders on suicide or suicidal behavior in late

associated with depression and depressive life (Sareen, 2011).

IV. COMPLEX PROCESSES

Detection, Treatment, and Management 419

DETECTION, TREATMENT, AND be reluctant to report psychological symptoms

MANAGEMENT (Lebowitz et al., 1997; Lyness et al., 1995).

Even if late-life mood and/or anxiety dis-

Despite the prevalence of late-life mood orders are recognized, estimates indicate that

and anxiety disorders, and their associated over 50% of older adults symptomatic for a

negative outcomes, these conditions are ame- clinical diagnosis do not use mental health ser-

nable to treatment through both pharmaco- vices (Klap, Unroe, & Unutzer, 2003; Klap et al.,

logic and psychological/behavioral methods 2003). Data from the NCS-R show that there is

(Alexopoulos et al., 2009; Bruce et al., 2004; a high prevalence of non-use of mental health

Charney et al., 2003; Wolitzky-Taylor, Castriotta, services for older Americans (aged 55 years

Lenze, Stanley, & Craske, 2010). Antidepressant and older) meeting criteria for DSM-IV mood

medications are the most common treatment for and anxiety disorders (Byers, Arean, & Yaffe,

depression in older persons (Mottram, Wilson, 2012), with the highest prevalence of non-

& Strobl, 2006) and because many antidepres- use for specific phobia (79.5%), social phobia

sants are safe and well-tolerated in this popu- (69.7%), and GAD (65.6%). In contrast, rates of

lation (Mamdani, Parikh, Austin, & Upshur, non-use were slightly lower for younger NCS-R

2000; Sonnenberg, Deeg, Comijs, van Tilburg, adults (aged 54 years and younger), with non-

& Beekman, 2008), they are considered a first- use approximately 60% for moderate to serious

line treatment for a spectrum of late-life depres- psychiatric disorders (Kessler, Demler et al.,

sive disorders, including clinically significant 2005). However, among older NCS-R respond-

depressive symptoms (Alexopoulos et al., 2001). ents with comorbid mood–anxiety disorders

Receiving therapy from a mental health profes- rates of non-use decreased to 50%, suggesting

sional, such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, or that severity of disorder increases use of men-

counselor, also has been found to be effective in tal health services (Byers, Arean, & Yaffe, 2012).

treating depression in this population (Cuijpers, Moreover, when considering the old-old and

van Straten, & Smit, 2006; Pinquart, Duberstein, oldest-old age groups (as documented from

& Lyness, 2006). However, although there are the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol

effective treatments for mood disorders and and Related Conditions (NESARC)), non-use

anxiety, there is widespread under-treatment of mental health services is extremely high

of these conditions in older persons across mul- with approximately 90% of those with an anxi-

tiple settings (Barry et al., 2012; Cuijpers et al., ety disorder not using services and over 70%

2006; Pinquart et al., 2006; Sonnenberg et al., of those with a mood disorder not using ser-

2008). This under-treatment has largely been vices (Mackenzie, Reynolds, Cairney, Streiner,

attributable to under-diagnosis resulting from a & Sareen, 2012). Research suggests that low per-

combination of physician, patient, and system- ceived need, moderate resources, and low moti-

level factors (Mitchell, Rao, & Vaze, 2010; Park vation for mental health care help to explain

& Unutzer, 2011). Physicians may misdiagnose why services may not be sought by older adults,

mood disorders as dementia, may mistakenly despite diagnosable mood and anxiety disor-

attribute symptoms of mood or anxiety disor- ders (Byers et al., 2012). Furthermore, it is only

ders as an acceptable response to illness or loss recently that parity in Medicare copayments

of social support in late life, or may have lim- for both physical and mental health conditions

ited time to address mental health during a rou- was established via the Medicare Improvements

tine office visit (Tai-Seale, McGuire, Colenda, for Patients and Providers Act [H.R. 6331; 110th

Rosen, & Cook, 2007). Older patients also may Congress; July 15, 2008]. Prior to this legislation,

IV. COMPLEX PROCESSES

420 21. RISK FACTORS FOR MOOD AND ANXIETY DISORDERS

Medicare recipients were required to pay 50% Trial (PROSPECT), a randomized controlled trial

for mental health services, and 20% copays for comparing treatment guidelines tailored for the

both physical and mental health services did not elderly with care management and usual care,

take effect until 2014. Research will be needed to collaborative care may be useful for reducing

determine the impact of this legislation on men- suicidal ideation in depressed elders. “Stepped

tal health services use in older persons. care” is another approach to managing depres-

The majority of older persons who are diag- sion in later life. This approach, which focuses

nosed with a mood and/or anxiety disorder on preventing the transition from subsyndro-

are subsequently treated and managed by pri- mal depression to major depressive disorder,

mary care physicians who often lack training in involves using methods such as watchful wait-

geriatric specialty care (Crystal, Sambamoorthi, ing, physical activity, and education before use

Walkup, & Akincigil, 2003; Harman, Veazie, & of antidepressants. Treating older persons with

Lyness, 2006). More than a decade ago, collabo- subsyndromal depression as a means of prevent-

rative care for depression was proposed as an ing a full-blown disorder may have significant

approach for optimizing treatment and manage- impact. Findings from the Amsterdam Study of

ment of depression in primary care. The collabo- the Elderly indicate that treating 5.8 older per-

rative care model emphasizes care management sons with subsyndromal depression may pre-

and education via a depression care manager. vent one of these individuals from experiencing

The Improving Mood—Promoting Access to the onset of clinical depression within 3 years

Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) program (Schoevers et al., 2006). These investigators esti-

for late-life depression, was the first multisite mate that treating all older persons with sub-

randomized control trial to compare collabora- syndromal depression could prevent 24.6% of

tive depression care with usual care in a sample new depression onsets during a 3-year period

comprised entirely of older persons (Unutzer (Schoevers et al., 2006).

et al., 2001, 2002). Results from the IMPACT Recent advances in neuroimaging have ena-

trial indicated that older persons receiving col- bled investigators to evaluate structural and

laborative care for depression had higher treat- functional differences in the brains of indi-

ment rates, higher satisfaction with depression viduals with and without late-life depres-

care, and greater improvements in depression sion, thereby determining who may be more

as compared with those receiving usual care. vulnerable to developing this disorder. The

Albeit modest, findings from the IMPACT trial use of structural imaging methods in late-

have also shown a positive impact of collabo- life depression, described in detail in two

rative care for depression on physical activ- reviews (Benjamin & Steffens, 2011; Hoptman,

ity and quality of life. Since publication of the Gunning-Dixon, Murphy, Lim, & Alexopoulos,

IMPACT trial results, many other studies have 2006), has been especially useful in determining

confirmed the effectiveness of collaborative care white matter lesion volume—a biomarker for

programs in decreasing depressive symptoms in classifying depression into vascular versus non-

older persons (Chang-Quan et al., 2009), includ- vascular depression (Sneed et al., 2008).

ing special populations of older persons such

as low-income elders, those with concomitant

chronic illnesses (Katon et al., 2010), patients CONCLUSION

with recent cardiac events (Huffman et al., 2014),

and those receiving home care. Furthermore, as The majority of older persons maintain high

evidenced through results from the Prevention levels of subjective well-being, even when

of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative faced with significant health problems and

IV. COMPLEX PROCESSES

REFERENCES 421

compromised physical function. However, the References

number of older persons experiencing mood

Alexopoulos, G. S. (2003). Vascular disease, depression, and

and/or anxiety disorders is expected to increase dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51(8),

with the continued growth of the older adult 1178–1180.

population. Late-life mood and anxiety disor- Alexopoulos, G. S. (2005). Depression in the elderly. Lancet,

ders are characterized by heterogeneity, vary- 365(9475), 1961–1970.

Alexopoulos, G. S. (2006). The vascular depression

ing widely in both severity and chronicity, and

hypothesis: 10 years later. Biological Psychiatry, 60(12),

ranging from subsyndromal depression and 1304–1305.

clinically significant depressive and/or anxi- Alexopoulos, G. S., Katz, I. R., Reynolds, C. F.,

ety symptoms to a full-blown major depressive Carpenter, D., Docherty, J. P., & Ross, R. W. (2001).

disorder or a co-morbid mood-anxiety disorder. Pharmacotherapy of depression in older patients: A

summary of the expert consensus guidelines. Journal of

Regardless of whether or not an older person’s

Psychiatric Practice, 7(6), 361–376.

symptoms confer a clinical diagnosis, individu- Alexopoulos, G. S., Meyers, B. S., Young, R. C., Campbell,

als who experience a late-life mood or anxiety S., Silbersweig, D., & Charlson, M. (1997). Vascular

disorder may be particularly vulnerable to both depression” hypothesis. Archives of General Psychiatry,

the onset and worsening of chronic illness and 54(10), 915–922.

Alexopoulos, G. S., Reynolds, C. F., III, Bruce, M. L., Katz,

disability, and they are at higher risk for suicide

I. R., Raue, P. J., Mulsant, B.H., et al. (2009). Reducing

and non-suicide-related mortality. Consequently, suicidal ideation and depression in older primary care

mood and anxiety disorders are a considerable patients: 24-month outcomes of the PROSPECT study.

public health problem for older persons. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(8), 882–890.

There is general consensus that risk factors Almeida, O. P., Draper, B., Snowdon, J., Lautenschlager, N. T.,

Pirkis, J., & Pfaff, J. J. (2012). Factors associated with

for late-life mood and anxiety disorders include

suicidal thoughts in a large community study of older

genetic vulnerability, physical illness and dis- adults. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of

ability, and psychosocial factors such as lack Mental Science, 201(6), 466–472.

of social support. While these risk factors have Avison, W. R., & Turner, R. J. (1988). Stressful life events

been evaluated independently, research exam- and depressive symptoms: Disaggregating the effects of

acute stressors and chronic strains. Journal of Health and

ining how these risk factors interact to affect the

Social Behavior, 29(3), 253–264.

onset and/or worsening of late-life mood and Barry, L. C., Abou, J. J., Simen, A. A., & Gill, T. M. (2012).

anxiety disorders is sorely needed. This line of Under-treatment of depression in older persons. Journal

research will also help to improve our under- of Affective Disorders, 136(3), 789–796.

standing of how some older persons are resil- Barry, L. C., Allore, H. G., Bruce, M. L., & Gill, T. M. (2009).

Longitudinal association between depressive symp-

ient in the face of challenges such as disability

toms and disability burden among older persons. The

or grief, while others are more apt to experience Journals of Gerontology. Series A: Biological Sciences and

late-life mood and anxiety disorders when con- Medical Sciences, 64(12), 1325–1332.

fronted with the same challenges. Barry, L. C., Allore, H. G., Guo, Z., Bruce, M. L., & Gill, T.

Effective treatments for late-life mood and M. (2008). Higher burden of depression among older

women: The effect of onset, persistence, and mortality

anxiety disorders are available. However, there

over time. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(2), 172–178.

is still substantial under-treatment of these dis- Barry, L. C., Murphy, T. E., & Gill, T. M. (2011). Depressive

orders in this population. With clinicians likely symptoms and functional transitions over time in older

to see increasing numbers of older patients in persons. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry,

the near future, improved understanding of 19(9), 783–791.

Barry, L. C., Soulos, P. R., Murphy, T. E., Kasl, S. V., & Gill,

risk factors is necessary to improve recognition

T. M. (2013). Association between indicators of dis-

of late-life mood and anxiety disorders and to ability burden and subsequent depression among older

help inform intervention and prevention efforts persons. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A: Biological

in older persons. Sciences and Medical Sciences, 68(3), 286–292.

IV. COMPLEX PROCESSES

422 21. RISK FACTORS FOR MOOD AND ANXIETY DISORDERS

Barry, L. C., Thorpe, R. J., Jr., Penninx, B. W., Yaffe, K., elderly home health care patients. The American Journal

Wakefield, D., & Simonsick, E. M. (2014). Race-related of Psychiatry, 159(8), 1367–1374.

differences in depression onset and recovery in older Butters, M. A., Young, J. B., Lopez, O., Aizenstein, H. J.,

persons over time: The health, aging, and body compo- Mulsant, B. H., & Becker, J. T. (2008). Pathways linking

sition study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, late-life depression to persistent cognitive impairment

22(7), 682–691. and dementia. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 10(3),

Beard, J. R., Cerda, M., Blaney, S., Ahern, J., Vlahov, D., & 345–357.

Galea, S. (2009). Neighborhood characteristics and Byers, A. L., Arean, P. A., & Yaffe, K. (2012). Low use of

change in depressive symptoms among older residents mental health services among older Americans with

of New York City. American Journal of Public Health, mood and anxiety disorders. Psychiatric Services, (63),

99(7), 1308–1314. 66–72.

Beckman, L. J. (1981). Effects of social interaction and chil- Byers, A. L., & Yaffe, K. (2011). Depression and risk of

dren’s relative inputs on older women’s psychological developing dementia. Nature Reviews Neurologica, 7(6),

well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 323–331.

41(6), 1075–1086. Byers, A. L., Yaffe, K., Covinsky, K. E., Friedman, M. B.,

Beekman, A. T., Copeland, J. R., & Prince, M. J. (1999). Bruce, M. L., & Bruce, M. L. (2010). High occurrence of

Review of community prevalence of depression in later mood and anxiety disorders among older adults: The

life. British Journal of Psychiatry, 174, 307–311. National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of

Beekman, A. T. F., Bremmer, M. A., Deeg, D. J. H., Van General Psychiatry, 67(5), 489–496.

Balkom, A. J. L. M., Smit, J. H., & Van Tilburg, W. (1998). Camus, V., Kraehenbuhl, H., Preisig, M., Bula, C. J., &

Anxiety disorders in later life: A report from the longi- Waeber, G. (2004). Geriatric depression and vascu-

tudinal aging study Amsterdam. International Journal of lar diseases: What are the links? Journal of Affective

Geriatric Psychiatry, 13(10), 717–726. Disorders, 81(1), 1–16.

Benjamin, S., & Steffens, D. C. (2011). Structural neuroim- Carnethon, M. R., Biggs, M. L., Barzilay, J. I., Smith, N. L.,

aging of geriatric depression. The Psychiatric Clinics of Vaccarino, V., & Siscovick, D. (2007). Longitudinal asso-

North America, 34(2), 423–435. ciation between depressive symptoms and incident

Berkman, L. F., & Kawachi, I. (2000). Social epidemiology. type 2 diabetes mellitus in older adults: The cardiovas-

New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc. cular health study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 167(8),

Blazer, D. G. (2003). Depression in late life: Review and 802–807.

commentary. Journals of Gerontology. Series A: Biological Cassel, J. (1976). The contribution of the social environ-

Sciences & Medical Sciences, 58(3), 249–265. ment to host resistance: The Fourth Wade Hampton

Blazer, D. G., II, & Hybels, C. F. (2005). Origins of depres- Frost Lecture. American Journal of Epidemiology, 104(2),

sion in later life. Psychological Medicine, 35(9), 1241–1252. 107–123.

Brenner, L. A., Betthauser, L. M., Homaifar, B. Y., Chang-Quan, H., Bi-Rong, D., Zhen-Chan, L., Yuan, Z.,

Villarreal, E., Harwood, J. E., & Huggins, J. A. (2011). Yu-Sheng, P., & Qing-Xiu, L. (2009). Collaborative care

Posttraumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury, interventions for depression in the elderly: A system-

and suicide attempt history among veterans receiv- atic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal

ing mental health services. Suicide & Life-Threatening of Investigative Medicine: The Official Publication of the

Behavior, 41(4), 416–423. American Federation for Clinical Research, 57(2), 446–455.

Brodaty, H., Luscombe, G., Parker, G., Wilhelm, K., Hickie, Charney, D. S., Reynolds, C. F., III, Lewis, L., Lebowitz, B.

I., & Mitchell, P. (2001). Early and late onset depression D., Sunderland, T., Alexopoulos, G. S., et al., (2003).

in old age: Different aetiologies, same phenomenology. Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance consensus

Journal of Affective Disorders, 66(2–3), 225–236. statement on the unmet needs in diagnosis and treat-

Bruce, M. L. (2001). Depression and disability in late life: ment of mood disorders in late life. Archives of General

Directions for future research. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 60(7), 664–672.

Psychiatry, 9(2), 102–112. Chen, M., Tse, L. A., Au, R. K., Yu, I. T., Wang, X. R., & Au,

Bruce, M. L., Ten Have, T. R., Reynolds, C. F., III, Katz, I. I., J. S. (2012). Mesothelioma and lung cancer mortality:

Schulberg, H. C., & Alexopoulos, G. S. (2004). Reducing A historical cohort study among asbestosis workers

suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in in Hong Kong. Lung Cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands),

depressed older primary care patients: A randomized 76(2), 165–170.

controlled trial. JAMA, 291(9), 1081–1091. Cobb, S. (1976). Presidential Address-1976. Social support

Bruce, M. L., McAvay, G. J., Raue, P. J., Brown, E. L., as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine,

Meyers, B. S., & Weber, C. (2002). Major depression in 38(5), 300–314.

IV. COMPLEX PROCESSES

REFERENCES 423

Cohen, C. I., Magai, C., Yaffee, R., & Walcott-Brown, L. Flicker, L. (2008). Vascular factors in geriatric psychia-

(2005). Racial differences in syndromal and subsyn- try: Time to take a serious look. Current Opinion in

dromal depression in an older urban population. Psychiatry, 21(6), 551–554.

Psychiatric Services (Washington, DC), 56(12), 1556–1563. Flicker, L. (2010). Cardiovascular risk factors, cerebrovascu-

Cole, M. G., & Dendukuri, N. (2003). Risk factors for lar disease burden, and healthy brain aging. Clinics in

depression among elderly community subjects: A sys- Geriatric Medicine, 26(1), 17–27.

tematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Forlani, C., Morri, M., Ferrari, B., Dalmonte, E., Menchetti,

Psychiatry, 160(6), 1147–1156. M., & Atti, A. R. (2014). Prevalence and gender dif-

Conner, K. R., Conwell, Y., & Duberstein, P. R. (2001). The ferences in late-life depression: A population-based

validity of proxy-based data in suicide research: A study study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(4),

of patients 50 years of age and older who attempted sui- 370–380.

cide. II. Life events, social support and suicidal behavior. Fremouw, W. J., dePerczel, M., & Ellis, T. E. (1990). Suicide

Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 104(6), 452–457. risk: Assessment and response guidelines. New York, NY:

Conwell, Y., Duberstein, P. R., & Caine, E. D. (2002). Risk Pergamon Press.

factors for suicide in later life. Biological Psychiatry, Gallo, J. J., Cooper-Patrick, L., & Lesikar, S. (1998). Depressive

52(3), 193–204. symptoms of whites and African Americans aged 60

Conwell, Y., Duberstein, P. R., Hirsch, J. K., Conner, K. R., years and older. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B:

Eberly, S., & Caine, E. D. (2010). Health status and sui- Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53(5), P277–P286.

cide in the second half of life. International Journal of Gaynes, B. N., West, S. L., Ford, C. A., Frame, P., Klein, J., &

Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(4), 371–379. Lohr, K. N. (2004). Screening for suicide risk in adults:

Conwell, Y., Van Orden, K., & Caine, E. D. (2011). Suicide A summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive

in older adults. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine, 140(10),

34(2), 451–468. 822–835.

Crystal, S., Sambamoorthi, U., Walkup, J. T., & Akincigil, Gill, T. M., Desai, M. M., Gahbauer, E. A., Holford, T. R., &

A. (2003). Diagnosis and treatment of depression in Williams, C. S. (2001). Restricted activity among com-

the elderly medicare population: Predictors, dispari- munity-living older persons: Incidence, precipitants,

ties, and trends. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, and health care utilization. Annals of Internal Medicine,

51(12), 1718–1728. 135(5), 313–321.

Cuijpers, P., van Straten, A., & Smit, F. (2006). Psychological De Groot, J. C., De Leeuw, F. E., Oudkerk, M., Hofman, A.,

treatment of late-life depression: A meta-analysis of Jolles, J., & Breteler, M. M. (2000). Cerebral white mat-

randomized controlled trials. International Journal of ter lesions and depressive symptoms in elderly adults.

Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(12), 1139–1149. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(11), 1071–1076.

Dennis, M., Baillon, S., Brugha, T., Lindesay, J., Stewart, R., Gum, A. M., King-Kallimanis, B., & Kohn, R. (2009).

& Meltzer, H. (2007). The spectrum of suicidal ideation Prevalence of mood, anxiety, and substance-abuse dis-

in Great Britain: Comparisons across a 16–74 years age orders for older Americans in the National Comorbidity

range. Psychological Medicine, 37(6), 795–805. Survey-Replication. The American Journal of Geriatric

Djernes, J. K. (2006). Prevalence and predictors of Psychiatry, 17(9), 769–781.

depression in populations of elderly: A review. Acta Ha, J. H. (2010). The effects of positive and negative sup-

Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 113(5), 372–387. port from children on widowed older adults’ psy-

Dombrovski, A. Y., Butters, M. A., Reynolds, C. F., III, chological adjustment: A longitudinal analysis.

Houck, P. R., Clark, L., & Szanto, K. (2008). Cognitive Gerontologist, 50(4), 471–481.

performance in suicidal depressed elderly: Preliminary Ha, J. H., & Ingersoll-Dayton, B. (2011). Moderators in the

report. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(2), relationship between social contact and psychological

109–115. distress among widowed adults. Aging & Mental Health,

Erlangsen, A., Zarit, S. H., & Conwell, Y. (2008). Hospital- 15(3), 354–363.

diagnosed dementia and suicide: A longitudinal Harman, J. S., Veazie, P. J., & Lyness, J. M. (2006). Primary

study using prospective, nationwide register data. The care physician office visits for depression by older

American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(3), 220–228. Americans. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(9),

Ferraro, K. F., & Farmer, M. M. (1996). Double jeopardy, 926–930.

aging as leveler, or persistent health inequality? A lon- Harris, T., Cook, D. G., Victor, C., DeWilde, S., & Beighton, C.

gitudinal analysis of white and black Americans. The (2006). Onset and persistence of depression in older

Journals of Gerontology. Series B: Psychological Sciences and people—results from a 2-year community follow-up

Social Sciences, 51(6), S319–S328. study. Age & Ageing, 35(1), 25–32.

IV. COMPLEX PROCESSES

424 21. RISK FACTORS FOR MOOD AND ANXIETY DISORDERS

Hasin, D. S., Goodwin, R. D., Stinson, F. S., & Grant, B. F. Kessler, R. C., Demler, O., Frank, R. G., Olfson, M., Pincus,

(2005). Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: H. A., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2005). Prevalence and treat-

Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on ment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. The New

Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Archives of General England Journal of Medicine, 16, 352(24), 2515–2523. 352.

Psychiatry, 62(10), 1097–1106. Klap, R., Unroe, K. T., & Unutzer, J. (2003). Caring for

Herrmann, L. L., Le Masurier, M., & Ebmeier, K. P. (2008). mental illness in the United States: A focus on older

White matter hyperintensities in late life depression: A adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 11(5),

systematic review. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, 517–524.

and Psychiatry, 79(6), 619–624. Klap, R., Unroe, K. T., Unutzer, J., Klap, R., Unroe, K. T.,

Hoptman, M. J., Gunning-Dixon, F. M., Murphy, C. F., & Unutzer, J. (2003). Caring for mental illness in the

Lim, K. O., & Alexopoulos, G. S. (2006). Structural United States: A focus on older adults. American Journal

neuroimaging research methods in geriatric depres- of Geriatric Psychiatry, 11(5), 517–524.

sion. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(10), Kohout, F. J., Berkman, L. F., Evans, D. A., & Cornoni-Huntley,

812–822. J. (1993). Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for

Huffman, J. C., Mastromauro, C. A., Beach, S. R., Celano, C. M., Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symp-

DuBois, C. M., & Januzzi, J. L. (2014). Collaborative care toms index. Journal of Aging & Health, 5(2), 179–193.

for depression and anxiety disorders in patients with Krishnan, K. R., Hays, J. C., & Blazer, D. G. (1997). MRI-

recent cardiac events: The Management of Sadness and defined vascular depression. The American Journal of

Anxiety in Cardiology (MOSAIC) randomized clinical Psychiatry, 154(4), 497–501.

trial. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(6), 927–935. LaVeist, T. A. (2005). Disentangling race and socioeconomic

Hybels, C. F., & Blazer, D. G. (2003). Epidemiology of late- status: A key to understanding health inequalities.

life mental disorders. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 19(4), Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy

663–696. of Medicine, 82(2 Suppl. 3), iii26–34.

Hybels, C. F., Blazer, D. G., & Pieper, C. F. (2001). Toward Lebowitz, B. D., Pearson, J. L., Schneider, L. S., Reynolds,

a threshold for subthreshold depression: An analysis of C. F., III, Alexopoulos, G. S., & Parmelee, P. (1997).

correlates of depression by severity of symptoms using Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life.

data from an elderly community sample. Gerontologist, Consensus statement update. JAMA, 278(14), 1186–1190.

41(3), 357–365. Lenze, E. (2003). Comorbidity of depression and anxiety in

Jang, Y., Borenstein, A. R., Chiriboga, D. A., & Mortimer, the elderly. Current Psychiatry Reports, 5(1), 62–67.

J. A. (2005). Depressive symptoms among African Lenze, E. J., Mulsant, B. H., Shear, M. K., Alexopoulos, G. S.,

American and white older adults. The Journals of Frank, E., & Reynolds, C. F. (2001). Comorbidity of

Gerontology. Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social depression and anxiety disorders in later life. Depression

Sciences, 60(6), P313–P319. and Anxiety, 14(2), 86–93.

Juurlink, D. N., Herrmann, N., Szalai, J. P., Kopp, A., & Lenze, E. J., Mulsant, B. H., Shear, M. K., Schulberg, H. C.,

Redelmeier, D. A. (2004). Medical illness and the risk Dew, M. A., & Begley, A. E. (2000). Comorbid anxi-

of suicide in the elderly. Archives of Internal Medicine, ety disorders in depressed elderly patients. American

164(11), 1179–1184. Journal of Psychiatry, (157), 722–728.

Katon, W. J., Lin, E., Russo, J., & Unutzer, J. (2003). Lichtenthal, W. G., Cruess, D. G., & Prigerson, H. G. (2004).

Increased medical costs of a population-based sam- A case for establishing complicated grief as a distinct

ple of depressed elderly patients. Archives of General mental disorder in DSM-V. Clinical Psychology Review,

Psychiatry, 60(9), 897–903. 24(6), 637–662.

Katon, W. J., Lin, E. H., Von Korff, M., Ciechanowski, P., Liebetrau, M., Steen, B., & Skoog, I. (2008). Depression

Ludman, E. J., & McCulloch, D. (2010). Collaborative as a risk factor for the incidence of first-ever stroke in

care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. 85-year-olds. Stroke, 39(7), 1960–1965.

The New England Journal of Medicine, 363(27), 2611–2620. Luoma, J. B., Martin, C. E., & Pearson, J. L. (2002). Contact

Kendler, K. S., Gardner, C. O., Gatz, M., & Pedersen, N. L. with mental health and primary care providers before

(2007). The sources of co-morbidity between major suicide: A review of the evidence. The American Journal

depression and generalized anxiety disorder in a Swedish of Psychiatry, 159(6), 909–916.

national twin sample. Psychological Medicine, 37, 453–462. Lyness, J. M., Cox, C., Curry, J., Conwell, Y., King, D. A., &

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, Caine, E. D. (1995). Older age and the underreporting of

K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and depressive symptoms. Journal of the American Geriatrics

age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the Society, 43(3), 216–221.

National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of Lyness, J. M., Kim, J., Tang, W., Tu, X., Conwell, Y., & Caine,

General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602. E. D. (2007). The clinical significance of subsyndromal

IV. COMPLEX PROCESSES

REFERENCES 425

depression in older primary care patients. American relationship between IADL/ADL disability and depres-

Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(3), 214–223. sive symptoms in late life. Journals of Gerontology.

Lyness, J. M., King, D. A., Cox, C., Yoediono, Z., & Caine, Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 57(4),

E. D. (1999). The importance of subsyndromal depres- P338–P347.

sion in older primary care patients: Prevalence and Oxman, T. E., Berkman, L. F., Kasl, S., Freeman, D. H., Jr., &

associated functional disability. Journal of the American Barrett, J. (1992). Social support and depressive symp-

Geriatrics Society, 47(6), 647–652. toms in the elderly. American Journal of Epidemiology,

Mackenzie, C. S., El-Gabalawy, R., Chou, K. L., & Sareen, J. 135(4), 356–368.

(2014). Prevalence and predictors of persistent versus Park, M., & Unutzer, J. (2011). Geriatric depression in pri-

remitting mood, anxiety, and substance disorders in a mary care. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 34(2),

national sample of older adults. The American Journal of 469–487. ix–x.

Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(9), 854–865. Paykel, E. S., Weissman, M., Prusoff, B. A., & Tonks, C. M.

Mackenzie, C. S., Reynolds, K., Cairney, J., Streiner, D. L., & (1971). Dimensions of social adjustment in depressed

Sareen, J. (2012). Disorder-specific mental health service women. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease,

use for mood and anxiety disorders: Associations with 152(3), 158–172.

age, sex, and psychiatric comorbidity. Depression and Paykel, E. S., & Weissman, M. M. (1973). Social adjust-

Anxiety, 29(3), 234–242. ment and depression. A longitudinal study. Archives of

Mamdani, M. M., Parikh, S. V., Austin, P. C., & Upshur, R. General Psychiatry, 28(5), 659–663.

E. (2000). Use of antidepressants among elderly sub- Pearlin, L. I., Lieberman, M. A., Menaghan, E. G., & Mullan,

jects: Trends and contributing factors. The American J. T. (1981). The stress process. Journal of Health & Social

Journal of Psychiatry, 157(3), 360–367. Behavior, 22(4), 337–356.

McIntosh, J. L., Santos, J. F., Hubbard, R. W., & Overholser, Penninx, B. W., Geerlings, S. W., Deeg, D. J., Van Eijk, J. T.,

J. C. (1994). Elder suicide: Research, theory, and treatment. Van Tilburg, W., & Beekman, A. T. (1999). Minor and

Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. major depression and the risk of death in older persons.

Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(10), 889–895.

(July 15, 2008). Penninx, B. W., Leveille, S., Ferrucci, L., Van Eijk, J. T., &

Metti, A. L., Cauley, J. A., Newman, A. B., Ayonayon, H. N., Guralnik, J. M. (1999). Exploring the effect of depres-

Barry, L. C., & Yaffe, K. (2013). Plasma beta amyloid level sion on physical disability: Longitudinal evidence from

and depression in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology. the established populations for epidemiologic studies

Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 68(1), 74–79. of the elderly. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9),

Mezuk, B., Rock, A., Lohman, M. C., & Choi, M. (2014). 1346–1352.

Suicide risk in long-term care facilities: A system- Pinquart, M., Duberstein, P. R., & Lyness, J. M. (2006).

atic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, Treatments for later-life depressive conditions: A meta-

29(12), 1198–1211. analytic comparison of pharmacotherapy and psy-

Mitchell, A. J., Rao, S., & Vaze, A. (2010). Do primary care chotherapy. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(9),

physicians have particular difficulty identifying late- 1493–1501.

life depression? A meta-analysis stratified by age. Pompili, M., Sher, L., Serafini, G., Forte, A., Innamorati, M.,

Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 79(5), 285–294. & Girardi, P. (2013). Posttraumatic stress disorder and

Mottram, P., Wilson, K., & Strobl, J. (2006). Antidepressants suicide risk among veterans: A literature review. The

for depressed elderly. Cochrane Database of Systematic Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 201(9), 802–812.

Reviews (Online) (1), CD003491. Prigerson, H. G., Frank, E., Kasl, S. V., Reynolds, C. F., III,

Nagumey, A. J., Reich, J. W., & Newsom, J. (2004). Gender Anderson, B., & Kupfer, D. J. (1995). Complicated grief

moderates the effects of independence and dependence and bereavement-related depression as distinct disorders:

desires during the social support process. Psychology Preliminary empirical validation in elderly bereaved

and Aging, 19(1), 215–218. spouses. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 152(1), 22–30.

National Institute of Mental Health, (2015). Suicide in Prigerson, H. G., Horowitz, M. J., Jacobs, S. C., Parkes, C.

America: Frequently asked questions. <http://www. M., Aslan, M., & Maciejewski, P. K. (2009). Prolonged

nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/suicide-in-amer- grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria pro-

ica/index.shtml>. Accessed 05.05.15. posed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Medicine, 6(8),

Older Americans, (2012). Key indicators of well-being. e1000121.

Hyattsville: Federal Interagency Forum on Aging- Sareen, J. (2011). Anxiety disorders and risk for suicide: Why

Related Statistics. such controversy? Depression and Anxiety, 28(11), 941–945.

Ormel, J., Rijsdijk, F. V., Sullivan, M., van Sonderen, E., Schoevers, R. A., Smit, F., Deeg, D. J., Cuijpers, P., Dekker,

& Kempen, G. I. J. M. (2002). Temporal and reciprocal J., & Beekman, A. T. (2006). Prevention of late-life

IV. COMPLEX PROCESSES

426 21. RISK FACTORS FOR MOOD AND ANXIETY DISORDERS

depression in primary care: Do we know where to use in the older population: Results from the LASA-

begin? The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(9), study over a period of 10 years. Journal of Affective

1611–1621. Disorders, 111(2–3), 299–305.

Schwarzbach, M., Luppa, M., Forstmeier, S., Konig, H. Steffens, D. C., Krishnan, K. R., Crump, C., & Burke, G. L.

H., & Riedel-Heller, S. G. (2014). Social relations and (2002). Cerebrovascular disease and evolution of

depression in late life-a systematic review. International depressive symptoms in the cardiovascular health

Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(1), 1–21. study. Stroke, 33(6), 1636–1644.

Seignourel, P. J., Kunik, M. E., Snow, L., Wilson, N., & Sun, X., Steffens, D. C., Au, R., Folstein, M., Summergrad,

Stanley, M. (2008). Anxiety in dementia: A critical P., & Qiu, W. Q. (2008). Amyloid-associated depression:

review. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(7), 1071–1082. A prodromal depression of Alzheimer disease? Archives

Shanmugasegaram, S., Russell, K. L., Kovacs, A. H., of General Psychiatry, 65(5), 542–550.

Stewart, D. E., & Grace, S. L. (2012). Gender and sex Tai-Seale, M., McGuire, T., Colenda, C., Rosen, D., &

differences in prevalence of major depression in coro- Cook, M. A. (2007). Two-minute mental health care for

nary artery disease patients: A meta-analysis. Maturitas, elderly patients: Inside primary care visits. Journal of the

73(4), 305–311. American Geriatrics Society, 55(12), 1903–1911.

Shear, M. K., Simon, N., Wall, M., Zisook, S., Neimeyer, R., Teodorczuk, A., O’Brien, J. T., Firbank, M. J., Pantoni, L.,

& Keshaviah, A. (2011). Complicated grief and related Poggesi, A., & Group, L. (2007). White matter changes

bereavement issues for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety, and late-life depressive symptoms: Longitudinal study.

28(2), 103–117. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental

Sheline, Y. I., Price, J. L., Vaishnavi, S. N., Mintun, M. A., Science, 191, 212–217.

Barch, D. M., & McKinstry, R. C. (2008). Regional white Thibodeau, M. A., Welch, P. G., Sareen, J., & Asmundson, G.

matter hyperintensity burden in automated segmen- J. G. (2013). Anxiety disorders are independently asso-

tation distinguishes late-life depressed subjects from ciated with suicide ideation and attempts: Propensity

comparison subjects matched for vascular risk factors. score matching in two epidemiological samples.

The American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(4), 524–532. Depression and Anxiety, 30(10), 947–954.

Sher, L., Braquehaid, M. D., & Casas, M. (2012). Thoits, P. A. (1995). Stress, coping, and social support pro-

Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and suicide cesses: Where are we? What is next? Journal of Health

in veterans. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 79(2), and Social Behavior, 53–79.

92–97. Thomas, A. J., Kalaria, R. N., & O’Brien, J. T. (2004).