Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Storer

Încărcat de

ruianzDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Storer

Încărcat de

ruianzDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

RUSSELL STORER

Ho Tzu Nyen: 4x4

The art historian Thomas Crow wrote in 1994 that “artists have become avid, if unpredictable, For the purposes of this text, I’ll focus on 4x4 and state my own interests—I was a participant

consumers of art history”, in that “consciousness of precedent has become very nearly the in the forum component, held on 16 October, 2005 at the Substation. I’d also like to note that

condition and definition of major artistic ambition”. To Crow, “almost every serious work writing about Ho’s work is a daunting prospect, not only due to its complexity and the formidable

of contemporary art recapitulates, on some explicit or implicit level, the historical sequence of erudition of the artist, but also because his work openly questions authoritative or singular

objects to which it belongs”.1 This condition recalls the ‘anxiety of influence’ famously described readings. Most art does to some degree, but rarely is this aspect so clearly foregrounded in the

by Harold Bloom, who posited that every new poem is in essence a reworking of earlier poems, work, forcing a consideration of one’s own role as an ‘authority’. The television component of

with creative misreading or misprision enabling younger poets (or ephebes) to develop distinctive 4x4, for example, pulls apart the format of art documentaries, with their omniscient presenters,

voices of their own.2 As artists build endlessly on what has gone before, the field has expanded from Robert Hughes to Sister Wendy. Ho’s twenty-two and a half minute episodes instead utilise

ever-outward, breaking down master narratives into what has been called a ‘post-historical’ a binary structure of two ‘oscillating’ hosts, one female and one male, each pair mapping certain

moment of radical plurality, in which every work of art could be said to contain only its own sets of power relations—employer/employee, director/assistant, boyfriend/girlfriend—and taking

history. The methodological and conceptual shifts that artists introduce to our understanding opposing views on the merits of the work in question. (This aspect has attracted some criticism

of art are often overlooked in formal art history however, given that they can be unpredictable, as essentialist, with the female roles positioned as progressive, if at times hysterical, arguing their

unruly, and even nihilistic, and are usually presented in the form of art itself. case against the reactionary male characters, who are aggressive, controlling and even violent.)

Ho’s presentation of artistic debate as an overwrought and in one case deadly struggle is

The Singaporean artist Ho Tzu Nyen is a serious student of art history (and of Bloom) and has humorously exaggerated, even camp, while tapping into long-standing anxieties about

made this historical research the material of his art. His works draw on various local histories— contemporary art’s irrelevance in an increasingly conservative and populist cultural and

the founding myth of Singapore in the video, painting and installation project Utama: Every political environment. This aspect again has specific resonances in Singapore, with its small,

Name in History is I (2003); conceptual lineages and transfers in Singaporean and Malaysian concentrated art scene operating inside a primarily mercantile society hyper-managed by

art in the lecture performance 2 South Seas, 3 Chairs, 4 Suits (2004) and four key Singaporean the State.

art works in 4x4: Episodes of Singapore Art (2005), which took the form of four television

episodes broadcast on Singapore’s Arts Central channel, a forum discussion and a diagrammatic, Each episode of 4x4 essentially ‘remakes’ a single art work. These are Cheong Soo Pieng’s painting

foldable postcard cube for distribution. In Ho’s work, history is presented as provisional and Tropical Life (1959), a key example of the ‘Nanyang’ school that fused Chinese, South-East Asian

subjective, framed by a dialectical structure of multiple and often contesting points of view. and Western modernist influences to create a local style; Cheo Chai Hiang’s conceptual work

Yet Ho also has a pedagogical impulse—the desire to recover and disseminate information 5ft x 5ft (Singapore River), an instruction submitted to and rejected by the Modern Art Society

that is little-known or understood to wide audiences and to encourage critical readings of that in 1972; Tang Da Wu’s protest performance Don’t Give Money to the Arts, in which the artist

information. In the context of Singapore, where contemporary art is marginal at best and history pointedly wore a jacket emblazoned with those words when meeting the President of Singapore;

is widely accepted as beginning in 1819 with the city-state’s founding by Sir Stamford Raffles, Ho’s and Lim Tzay Chuen’s Alter #11 (2002), an as yet unrealised action involving a bullet being fired

project contains a certain urgency, with its desire to engage broad audiences and encourage debate. into a gallery, requiring an inordinate amount of bureaucratic negotiation by the artist. Ho’s

broadsheet 43

4x4’s utopian impulse to propagate these works into the Singaporean consciousness—building a

virtual community of shared knowledge—as well as to promote his artist colleagues and influences,

can also be viewed in relation to a broader system of artistic collectivity. The role of artists’

collectives and collaborations has been crucial to the development of Singaporean contemporary

art practice, as elsewhere, arising in part as a response to the absence of a strong and supportive

critical and institutional framework. With a few key exceptions, art historical research in Singapore

has largely been borne by artists themselves, documenting, archiving and writing about the

practices of their peers.4 It was perhaps with a tongue in his cheek that Ho put together the forum

consisting of art historians, critics and curators who over the past decade or more have been closely

engaged with contemporary art in Singapore.5 The forum formalised the discursiveness at the

heart of 4x4, bringing to attention the rituals of artistic debate while providing the opportunity

to extend the ideas proposed in the episodes. Watched over by the artist from the hidden vantage

point of the sound mixing booth, the panel participants represented an official or institutional

selection of these works spans a range of practices and periods, necessarily compressed within history, separated from the artists in the audience.6 It didn’t occur to me until later that this was

Singapore’s short art history, yet also pinpoints shared themes—a sense of failure or irresolution, a a humorous gesture, performed in the Substation’s theatre, with the participants acting out their

strong concern for local conditions and the uneasy presence of Western art styles. Unified by their roles as Ho directed from above.

stark, white screen format, like a sequence of white cube galleries, the episodes playfully recreate

(and in the case of Cheo and Lim’s works, realise for the first time) each work as a narrative, Notes

1

Thomas Crow, ‘Unwritten Histories of Conceptual Art: Against Visual Culture’, in Crow, New Haven and London:

rather than an object or ‘moment’, placing it in the flow of history. The works appear not as a Modern Art in the Common Culture, Yale University Press, 1996: 212

direct representation but as a series of contrasting readings and discourses, incorporating pictorial 2

See Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry, New York: Oxford University Press, 1973

analysis, biography, social history, Marxist theory and feminism. While his strategy is reminiscent

3

of some appropriation art of previous decades, it presents multiple versions of the original, rather Ho Tzu Nyen, email correspondence with the author, 31 January 2006

than treating it as a singular sign. The works here appear as porous and vulnerable, even as Ho is 4

These could include the archive projects of Koh Nguang How, the Women in the Arts network convened by Amanda

emphasising their iconic status. Heng and others, the research projects and residencies organised by the artist-run space p-10, the Bali Project

undertaken by Ho and other members of The Artists Village and the art journal Vehicle published by the artist-run

space Plastique Kinetic Worms

Ho consciously rehearses Bloom’s image of the ephebe tackling the art of the past as a way

5

to move forward, yet rather than sublimating the original, brings it to the surface. His work The list of forum participants is listed by Lee Weng Choy in his text elsewhere in this issue

functions as a platform to disseminate these works, bringing them back to life so that they 6

Cheo Chai Hiang pointed out at the forum that there were no artists on the panel, although Ray Langenbach replied

can be re-evaluated. His choice of ‘unstable’ or unrealised art works is crucial in this regard; in that he worked as an artist

Cheo’s episode, for example, Ho clearly presents his notion of the failed or repressed art work

as ‘unfinished business’, forever doomed to return and haunt the present like Hamlet’s ghost.

In bringing these works into the present, enabling unfinished works to be finished, or ephemeral

Opposite page: Ho Tzu Nyen, still from Episode 1, 4X4—Episodes of Singapore Art, 2005

actions to be restaged (a popular phenomenon of late—for example Marina Abramovic’s 2005 Above: Ho Tzu Nyen, still from Episode 2, 4X4—Episodes of Singapore Art, 2005

restagings of performances by Beuys, Export, Acconci and others; or the Short History of Below: Ho Tzu Nyen, still from Episode 4, 4X4—Episodes of Singapore Art, 2005

Photos ourtesy the artist

Performance series, held at London’s Whitechapel Art Gallery in 2002–03). Ho performs a

double manoeuvre of honouring and promoting his unsung heroes while emptying them out

and parasitically occupying their space, inserting himself into history; as Ho notes, “discussions

of these works must (now) also engage with 4x4.”3 The presence of the artists in 4x4 is invisible,

shadowy or imprecise; in the episode that most requires the artist to be represented, Tang Da

Wu—The Most Radical Gesture, the figure of Tang is played by a non-look-alike, the artist John

Low, who was also selected for his deadpan lack of acting finesse. The art-documentary’s romantic

conceit of the artist at work, epitomised by the famous footage of Jackson Pollock, is rejected

outright by Ho, encouraging contrasting readings of the works by the audience unencumbered

by authorship.

In his use of television, Ho pursues his interest in working through the problems and limits of

specific mediums. For the episodes on Tang and Lim in particular, his scripts discuss the use of

photography, hype, gossip and publicity as means of disseminating particular art works, all crucial

aspects of television broadcasting and the mass media in general. The motif of the television set

as frame is also dominant in Lim’s episode as it discusses the ‘invisible’ art work that requires

such forums to exist. By broadcasting these four works as television, Ho thus attempts to retain

a certain fidelity to their spirit and intention, at the same time as critiquing the conventions and

expectations of the form. The other side of television of course is its audience, and Ho’s use of Arts

Central to reach beyond the gallery certainly continues the legacy of conceptual art in its desire to

break free of the art system and find new forms of circulation and distribution. The ‘success’ of this

enterprise, as with the conceptual art of the 1960s and ’70s, is debatable; at the forum for example,

it became evident that few of its predominantly art-world audience had actually seen the episodes,

and its overall viewer figures were relatively low. Yet the fact that such innovative and ambitious

programs were funded, produced and transmitted at all is testament to the skills of the artist and

his team in negotiating with State and media officials and maximising available opportunities, a

process with clear parallels to Lim’s experiments in bureaucracy and administration.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- POLLOCK, G. PARKER, R. - Old Mistresses. Women, Art and Ideology PDFDocument218 paginiPOLLOCK, G. PARKER, R. - Old Mistresses. Women, Art and Ideology PDFAnto Fabrega100% (9)

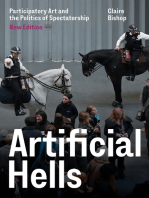

- Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of SpectatorshipDe la EverandArtificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of SpectatorshipEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (12)

- BARTHES That Old Thing ArtDocument4 paginiBARTHES That Old Thing ArtAfonso BarreiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Buchloh FormalismAndHistoricity ChangingConceptsSince1945Document32 paginiBuchloh FormalismAndHistoricity ChangingConceptsSince1945insulsus100% (1)

- Tjclark Social History of Art PDFDocument10 paginiTjclark Social History of Art PDFNicole BrooksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Entry Points. Resonating Punk, Performance, and ArtDocument57 paginiEntry Points. Resonating Punk, Performance, and ArtMinor Compositions100% (8)

- The Rules of Art Now - J StallabrassDocument10 paginiThe Rules of Art Now - J StallabrassGuy BlissettÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pictures As DramasDocument5 paginiPictures As Dramasgm2240Încă nu există evaluări

- Rubens Mano On Light and Power: CalçadaDocument4 paginiRubens Mano On Light and Power: Calçadaj00000000Încă nu există evaluări

- Ann Hui As A Female FilmmakerDocument63 paginiAnn Hui As A Female FilmmakerWong Siu WoonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acting in The RealDocument4 paginiActing in The RealboevskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hall S - Black Diaspora Artists in Britain - Three Moments' in Post-War HistoryDocument24 paginiHall S - Black Diaspora Artists in Britain - Three Moments' in Post-War HistoryHeliosa von OpetiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art Appreciation Module 4Document3 paginiArt Appreciation Module 4Michael Anthony EnajeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Looking For The Political Theatre of TodayDocument17 paginiLooking For The Political Theatre of TodayMargaridaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Frank O'Hara's Process PoemsDocument11 paginiFrank O'Hara's Process PoemsRita AgostiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Subversive SignsDocument5 paginiSubversive SignsFernando García100% (1)

- Line Form Colour ActionDocument10 paginiLine Form Colour ActionBruna KoerichÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ann Hui's Song of The Exile-Hong Kong University Press (2010)Document161 paginiAnn Hui's Song of The Exile-Hong Kong University Press (2010)LU HONG(대학원학생/일반대학원 영어영문학과) Încă nu există evaluări

- Introduction: "Pop Since 1949": Nigel WhiteleyDocument13 paginiIntroduction: "Pop Since 1949": Nigel WhiteleyMilica Amidzic100% (1)

- Contemporary Chinese Art PrimaryDocument3 paginiContemporary Chinese Art Primary867478Încă nu există evaluări

- Wole Soyinka Abstracts 15Document16 paginiWole Soyinka Abstracts 15Sinead MasonÎncă nu există evaluări

- NothingDocument49 paginiNothingrainer kohlbergerÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Drum, A Drum - Macbeth Doth ComeDocument17 paginiA Drum, A Drum - Macbeth Doth ComemfstÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alloway Lawrence 1962 2004 Pop Since 1949Document13 paginiAlloway Lawrence 1962 2004 Pop Since 1949Amalia WojciechowskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Florian Malzacher, 'Cause & Result', In: Frakcija #55: Curating Performing ArtsDocument10 paginiFlorian Malzacher, 'Cause & Result', In: Frakcija #55: Curating Performing ArtsjessevanwindenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stories Out of BurmaDocument24 paginiStories Out of BurmaJorn MiddelborgÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Concise Introduction To Intercultural TheatreDocument25 paginiA Concise Introduction To Intercultural TheatreAlix de Saint HippolyteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Same Line Twice - Wai Pongyu and Hung Fai - Artistic Collaboration As A Political AllegoryDocument7 paginiSame Line Twice - Wai Pongyu and Hung Fai - Artistic Collaboration As A Political AllegoryPAUL SERFATYÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rebecca Groves, William Forsythe and The Practice of Choreography: It Starts From Any Point, Ed. Stephen Spier (Book Review)Document5 paginiRebecca Groves, William Forsythe and The Practice of Choreography: It Starts From Any Point, Ed. Stephen Spier (Book Review)limnisseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ranciere and Aesthetics of ListeningDocument11 paginiRanciere and Aesthetics of Listeningcalum_neillÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ferrari Pop Goes The Avant-Garde CH. 7 (Anarchist 228-245)Document28 paginiFerrari Pop Goes The Avant-Garde CH. 7 (Anarchist 228-245)Ricardo BaltazarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Staging Critical History Within The Space of The Beat or What Cultural Historians Can Learn From Public Enemy, NTM, MC Solaar & George ClintonDocument20 paginiStaging Critical History Within The Space of The Beat or What Cultural Historians Can Learn From Public Enemy, NTM, MC Solaar & George Clintonvincenzo.martorellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Light in Hopper's PaintingsDocument33 paginiLight in Hopper's PaintingsDoniemdoniemÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10.4324 9781315728346-15 ChapterpdfDocument10 pagini10.4324 9781315728346-15 ChapterpdfNaresh AdhikariÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Stage in Search of A Tradition - The Dynamics of Form and Content in Post-Maoist Theatre: Xiaomei ChenDocument23 paginiA Stage in Search of A Tradition - The Dynamics of Form and Content in Post-Maoist Theatre: Xiaomei ChenMaiko CheukachiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lehman PostdramaticoDocument4 paginiLehman PostdramaticoraulhgarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Artist/Critic?Document4 paginiArtist/Critic?AlexnatalieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abstract Expressionism Research PaperDocument5 paginiAbstract Expressionism Research Paperfvf442bf100% (1)

- Shakespeare and Modern Version of His PlaysDocument22 paginiShakespeare and Modern Version of His PlaysMaja MileticÎncă nu există evaluări

- DansaekhwaDocument20 paginiDansaekhwamorleysimonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Year 1 Summer Essay, MarkedDocument5 paginiYear 1 Summer Essay, MarkedEsminusÎncă nu există evaluări

- LIB 1016 Mod. 1 Cont PDFDocument29 paginiLIB 1016 Mod. 1 Cont PDFKSSK 9250Încă nu există evaluări

- UDocument17 paginiUAtlanta CapitalÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Role of The Artist As A Social Critic - As Interpreted Through The ArtDocument94 paginiThe Role of The Artist As A Social Critic - As Interpreted Through The Artpatrik sarekozyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abstraction Eight Statements October 143Document49 paginiAbstraction Eight Statements October 143Egor Sofronov100% (2)

- The Aesthetic Ear Sound Art Jacques Ranci Re and The Politics of Listening-2Document12 paginiThe Aesthetic Ear Sound Art Jacques Ranci Re and The Politics of Listening-2Ana CancelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 3 Art As Communication of Emotion Art Appreciation 20240324 103625 0000Document8 paginiLesson 3 Art As Communication of Emotion Art Appreciation 20240324 103625 0000Mampusti MarlojaykeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Student Sample Notes and Rothko EssayDocument3 paginiStudent Sample Notes and Rothko Essayapi-211813321Încă nu există evaluări

- Eva+Mak+ +Amikam+Toren+-+the+Phenomenology+of+the+Fragment+ +jan+2015+ +Full+TextDocument20 paginiEva+Mak+ +Amikam+Toren+-+the+Phenomenology+of+the+Fragment+ +jan+2015+ +Full+TextToby J Lloyd-JonesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Everything We Have Been Afraid To Ask About Amfiteater PDFDocument10 paginiEverything We Have Been Afraid To Ask About Amfiteater PDFtomqzÎncă nu există evaluări

- CAMP FIRES - Q&A With Robin MetcalfeDocument2 paginiCAMP FIRES - Q&A With Robin MetcalfeMaiiMorsiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Postmodern Attitudes Towards ArtDocument12 paginiPostmodern Attitudes Towards ArtAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Imitation and Creativity in Japanese Arts: From Kishida Ryusei to Miyazaki HayaoDe la EverandImitation and Creativity in Japanese Arts: From Kishida Ryusei to Miyazaki HayaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- "Abstract Expressionism" Contemporary Example Robert Slingsby - One of Contemporary AbstractDocument6 pagini"Abstract Expressionism" Contemporary Example Robert Slingsby - One of Contemporary AbstractEunji eunÎncă nu există evaluări

- Projection As Performance IntermedialityDocument19 paginiProjection As Performance IntermedialityNexuslord1kÎncă nu există evaluări

- Positively White Cube RevisitedDocument4 paginiPositively White Cube RevisitedeleendeprezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lucy Lippard - Eccentric AbstractionDocument8 paginiLucy Lippard - Eccentric AbstractiongabrielaÎncă nu există evaluări