Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

A New Kind of Ancestor

Încărcat de

ilanigalDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

A New Kind of Ancestor

Încărcat de

ilanigalDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

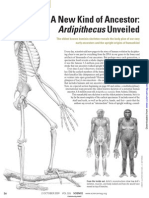

NEWSFOCUS

A New Kind of Ancestor:

Ardipithecus Unveiled

The oldest known hominin skeleton reveals the body plan of our very

early ancestors and the upright origins of humankind

Every day, scientists add new pages to the story of human evolution by decipher-

ing clues to our past in everything from the DNA in our genes to the bones and

artifacts of thousands of our ancestors. But perhaps once each generation, a

spectacular fossil reveals a whole chapter of our prehistory all at once. In 1974,

it was the famous 3.2-million-year-old skeleton “Lucy,” who proved in one

stroke that our ancestors walked upright before they evolved big brains.

Ever since Lucy’s discovery, researchers have wondered what came before

her. Did the earliest members of the human family walk upright like Lucy or on

their knuckles like chimpanzees and gorillas? Did they swing through the trees

or venture into open grasslands? Researchers have had only partial, fleeting

glimpses of Lucy’s own ancestors—the earliest hominins, members of the group

that includes humans and our ancestors (and are sometimes called hominids).

Now, in a special section beginning on page 60 and online, a multidisciplinary

international team presents the oldest known skeleton of a potential human

ancestor, 4.4-million-year-old Ardipithecus ramidus from Aramis, Ethiopia.

This remarkably rare skeleton is not the oldest putative hominin, but it is

by far the most complete of the earliest specimens. It includes most of the

skull and teeth, as well as the pelvis, hands, and feet—parts that the

authors say reveal an “intermediate” form of upright walking, consid-

CREDITS: ILLUSTRATIONS © 2009, J. H. MATTERNES

From the inside out. Artist’s reconstructions show how Ardi’s

skeleton, muscles, and body looked and how she would have

moved on top of branches.

36 2 OCTOBER 2009 VOL 326 SCIENCE www.sciencemag.org

Published by AAAS

Ardipithecus ramidus NEWSFOCUS

ered a hallmark of hominins. “We thought Lucy was the find of the “The authors … are framing the debate that will inevitably follow,”

century but, in retrospect, it isn’t,” says paleoanthropologist Andrew because the description and interpretation of the finds are entwined,

Hill of Yale University. “It’s worth the wait.” says Pilbeam. “My first reaction is to be skeptical about some of the

To some researchers’ surprise, the female skeleton doesn’t look conclusions,” including that human ancestors never went through a

much like a chimpanzee, gorilla, or any of our closest living primate chimpanzee-like phase. Other researchers are focusing intently on

relatives. Even though this species probably lived soon after the dawn the lower skeleton, where some of the anatomy is so primitive that

of humankind, it was not transitional between African apes and they are beginning to argue over just what it means to be “bipedal.”

humans. “We have seen the ancestor, and it is not a chimpanzee,” says The pelvis, for example, offers only “circumstantial” evidence for

paleoanthropologist Tim White of the University of California, Berke- upright walking, says Walker. But however the debate about Ardi’s

ley, co-director of the Middle Awash research group, which discovered locomotion and identity evolves, she provides the first hard evidence

and analyzed the fossils. that will inform and constrain future ideas

Instead, the skeleton and pieces of at least 35 additional individuals about the ancient hominin bauplan.

of Ar. ramidus reveal a new type of early hominin that was neither

chimpanzee nor human. Although the team suspects that Ar. ramidus

Online

sciencemag.org Digging it

may have given rise to Lucy’s genus, Australopithecus, the fossils Podcast interview

The first glimpse of this strange creature came

“show for the first time that there is some new evolutionary grade of with author on 17 December 1992 when a former graduate

hominid that is not Australopithecus, that is not Homo,” says paleontol- Ann Gibbons on student of White’s, Gen Suwa, saw a glint

ogist Michel Brunet of the College de France in Paris. Ardipithecus and among the pebbles of the desert pavement

In 11 papers published in this issue and online, the team of 47 fieldwork in the Afar. near the village of Aramis. It was the polished

researchers describes how Ar. ramidus looked and moved. The skele- surface of a tooth root, and he immediately

ton, nicknamed “Ardi,” is from a female who lived in a woodland knew it was a hominin molar. Over the next few days, the team scoured

(see sidebar, p. 40), stood about 120 centimeters tall, and weighed the area on hands and knees, as they do whenever an important piece

about 50 kilograms. She was thus as big as a chimpanzee and had a of hominin is found (see story, p. 41), and collected the lower jaw of a

brain size to match. But she did not knuckle-walk or swing through child with the milk molar still attached. The molar was so primitive that

the trees like living apes. Instead, she walked upright, planting her the team knew they had found a hominin both older and more primitive

CREDITS: (LEFT) C. O. LOVEJOY ET AL., SCIENCE; (TOP) G. SUWA ET AL., SCIENCE; (BOTTOM) C. O. LOVEJOY ET AL., SCIENCE; (RIGHT) C. O. LOVEJOY ET AL., SCIENCE

feet flat on the ground, perhaps eating nuts, insects, and small mam- than Lucy. Yet the jaw also had derived traits—novel evolutionary char-

mals in the woods. acters—shared with Lucy’s species, Au. afarensis, such as an upper

She was a “facultative” biped, say the authors, still living in both canine shaped like a diamond in side view.

worlds—upright on the ground but also able to move on all fours on The team reported 15 years ago in Nature that the fragmentary

top of branches in the trees, with an opposable big toe to grasp limbs. fossils belonged to the “long-sought potential root species for the

“These things were very odd creatures,” says paleoanthropologist Hominidae.” (They first called it Au. ramidus, then, after finding

Alan Walker of Pennsylvania State University, University Park. “You parts of the skeleton, changed it to Ar. ramidus—for the Afar words

know what Tim [White] once said: If you wanted to find something for “root” and “ground.”) In response to comments that he needed leg

that moved like these things, you’d have to go to the bar in Star Wars.” bones to prove Ar. ramidus was an upright hominin, White joked that

Most researchers, who have waited 15 years for the publication of he would be delighted with more parts, specifically a thigh and an

this find, agree that Ardi is indeed an early hominin. They praise the intact skull, as though placing an order.

detailed reconstructions needed to piece together the crushed bones. Within 2 months, the team delivered. In November 1994, as the fos-

“This is an extraordinarily impressive work of reconstruction and sil hunters crawled up an embankment, Berkeley graduate student

description, well worth waiting for,” says paleoanthropologist David Yohannes Haile-Selassie of Ethiopia, now a paleoanthropologist at the

Pilbeam of Harvard University. “They did this job very, very well,” Cleveland Museum of Natural History in Ohio, spotted two pieces of a

agrees neurobiologist Christoph Zollikofer of the University of bone from the palm of a hand. That was soon followed by pieces of a

Zurich in Switzerland. pelvis; leg, ankle, and foot bones; many of the bones of the hand and

But not everyone agrees with the team’s interpretations about how arm; a lower jaw with teeth—and a cranium. By January 1995, it was

Ar. ramidus walked upright and what it reveals about our ancestors. apparent that they had made the rarest of rare finds, a partial skeleton.

Unexpected anatomy. Ardi has an opposable toe (left) and flexible hand (right);

her canines (top center) are sized between those of a human (top left) and chimp

(top right); and the blades of her pelvis (lower left) are broad like Lucy’s (yellow).

www.sciencemag.org SCIENCE VOL 326 2 OCTOBER 2009

37

Published by AAAS

NEWSFOCUS Ardipithecus ramidus

FOSSILS OF THE HUMAN FAMILY HOMO H. floresiensis

Indonesia

H. heidelbergensis

Europe

Kenyanthropus platyops?

Kenya

H. habilis H. erectus H. neanderthalensis

Sub-Saharan Europe and Asia

SAHELANTHROPUS Africa Africa and Asia

AUSTRALOPITHECUS ? H. sapiens

ARDIPITHECUS Au. anamensis Au. garhi Au. rudolfensis Worldwide

Kenya, Ethiopia Ethiopia Eastern Africa

S. tchadensis Ar. kadabba Ar. ramidus

Toumaï Ethiopia Ardi Au. afarensis

Chad Ethiopia, Kenya Lucy

Ethiopia, Au. africanus Au. robustus

Tanzania Taung Child South Africa

ORRORIN South Africa

7 Million Years Ago

1 Million Years Ago

Au. bahrelghazali?

O. tugenensis Abel

Millennium Man Chad

Kenya Au. aethiopicus Au. boisei

Eastern Africa Eastern Africa

Today

6

2

Miocene Epoch Pliocene Epoch Pleistocene Epoch Holocene Epoch

Filling a gap. Ardipithecus provides a link between earlier and later hominins, as seen in this timeline showing important hominin fossils and taxa.

It is one of only a half-dozen such skeletons known from more than on the task. “You go piece by piece.”

CREDITS: (TIMELINE LEFT TO RIGHT) L. PÉRON/WIKIPEDIA, B. G. RICHMOND ET AL., SCIENCE 319, 1662 (2008); © T. WHITE 2008; WIKIPEDIA; TIM WHITE; TIM WHITE; (PHOTO) D. BRILL

1 million years ago, and the only published one older than Lucy. Once he had reassembled the pieces in a digital reconstruction, he

It was the find of a lifetime. But the team’s excitement was tempered and paleoanthropologist Berhane Asfaw of the Rift Valley Research

by the skeleton’s terrible condition. The bones literally crumbled when Service in Addis Ababa compared the skull with those of ancient and

touched. White called it road kill. And parts of the skeleton had been living primates in museums worldwide. By March of this year, Suwa

trampled and scattered into more than 100 fragments; the skull was was satisfied with his 10th reconstruction. Meanwhile in Ohio,

crushed to 4 centimeters in height. The researchers decided to remove Lovejoy made physical models of the pelvic pieces based on the orig-

entire blocks of sediment, covering the blocks in plaster and moving inal fossil and the CT scans, working closely with Suwa. He is also sat-

them to the National Museum of isfied that the 14th version of the

Ethiopia in Addis Ababa to finish pelvis is accurate. “There was an

excavating the fossils. Ardipithecus that looked just like

It took three field seasons to that,” he says, holding up the final

uncover and extract the skeleton, model in his lab.

repeatedly crawling the site to

gather 100% of the fossils pres- Putting their heads together

ent. At last count, the team had As they examined Ardi’s skull,

cataloged more than 110 speci- Suwa and Asfaw noted a number

mens of Ar. ramidus, not to men- of characteristics. Her lower face

tion 150,000 specimens of fossil had a muzzle that juts out less than

plants and animals. “This team a chimpanzee’s. The cranial base is

seems to suck fossils out of the short from front to back, indicat-

earth,” says anatomist C. Owen ing that her head balanced atop the

Lovejoy of Kent State University spine as in later upright walkers,

in Ohio, who analyzed the post- Fossil finders. Tim White and local Afar fossil hunters pool their finds after rather than to the front of the spine,

cranial bones but didn’t work in scouring the hillside at Aramis. as in quadrupedal apes. Her face is

the f ield. In the lab, he gently in a more vertical position than in

unveils a cast of a tiny, pea-sized sesamoid bone for effect. “Their chimpanzees. And her teeth, like those of all later hominins, lack the

obsessiveness gives you—this!” daggerlike sharpened upper canines seen in chimpanzees. The team

White himself spent years removing the silty clay from the fragile realized that this combination of traits matches those of an even older

fossils at the National Museum in Addis Ababa, using brushes, skull, 6-million to 7-million-year-old Sahelanthropus tchadensis,

syringes, and dental tools, usually under a microscope. Museum tech- found by Brunet’s team in Chad. They conclude that both represent an

nician Alemu Ademassu made a precise cast of each piece, and the early stage of human evolution, distinct from both Australopithecus and

team assembled them into a skeleton. chimpanzees. “Similarities with Sahelanthropus are striking, in that it

Meanwhile in Tokyo and Ohio, Suwa and Lovejoy made virtual also represents a first-grade hominid,” agrees Zollikofer, who did a

reconstructions of the crushed skull and pelvis. Certain fossils were three-dimensional reconstruction of that skull.

taken briefly to Tokyo and scanned with a custom micro–computed Another, earlier species of Ardipithecus—Ar. kadabba, dated

tomography (CT) scanner that could reveal what was hidden inside the from 5.5 million to 5.8 million years ago but known only from teeth

bones and teeth. Suwa spent 9 years mastering the technology to and bits and pieces of skeletal bones—is part of that grade, too. And

reassemble the fragments of the cranium into a virtual skull. “I used 65 Ar. kadabba’s canines and other teeth seem to match those of a third

pieces of the cranium,” says Suwa, who estimates he spent 1000 hours very ancient specimen, 6-million-year-old Orrorin tugenensis from

38 2 OCTOBER 2009 VOL 326 SCIENCE www.sciencemag.org

Published by AAAS

Ardipithecus ramidus NEWSFOCUS

Kenya, which also has a

thighbone that appears

to have been used for

upright walking (Science,

21 March 2008, p. 1599).

So, “this raises the in-

triguing possibility that

we’re looking at the same

genus” for specimens

now put in three genera,

says Pilbeam. But the

discoverers of O. tuge-

nensis aren’t so sure. “As for Ardi and Orrorin being the same genus,

no, I don’t think this is possible, unless one really wants to accept an

unusual amount of variability” within a taxon, says geologist Martin

Pickford of the College de France, who found Orrorin with Brigitte

Senut of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris.

Whatever the taxonomy of Ardipithecus and the other very ancient

hominins, they represent “an enormous jump to Australopithecus,” the

next hominin in line (see timeline, p. 38), says australopithecine expert

William Kimbel of Arizona State University, Tempe. For example,

although Lucy’s brain is only a little larger than that of Ardipithecus,

Lucy’s species, Au. afarensis, was an adept biped. It walked upright

like humans, venturing increasingly into more diverse habitats,

including grassy savannas. And it had lost its opposable big toe, as

seen in 3.7-million-year-old footprints at Laetoli, Tanzania, reflecting

an irreversible commitment to life on the ground.

Lucy’s direct ancestor is widely considered to be Au. anamensis,

a hominin whose skeleton is poorly known, although its shinbone

suggests it walked upright 3.9 million to 4.2 million years ago in Dream team. Gen Suwa (left) in Tokyo focused on the skull; C. Owen Lovejoy (top

Kenya and Ethiopia. Ardipithecus is the current leading candidate right) in Kent, Ohio, studied postcranial bones; and Yohannes Haile-Selassie and

for Au. anamensis’s ancestor, if only because it’s the only putative Berhane Asfaw found and analyzed key fossils in Ethiopia.

hominin in evidence between 5.8 million and 4.4 million years ago.

Indeed, Au. anamensis fossils appear in the Middle Awash region climber that probably moved on flat hands and feet on top of branches

just 200,000 years after Ardi. in the midcanopy, a type of locomotion known as palmigrady. For

CREDITS (TOP TO BOTTOM): TIM WHITE; BOB CHRISTY/NEWS AND INFORMATION, KENT STATE UNIVERSITY; TIM WHITE

example, four bones in the wrist of Ar. ramidus gave it a more flexible

Making strides hand that could be bent backward at the wrist. This is in contrast to the

But the team is not connecting the dots between Au. anamensis and hands of knuckle-walking chimpanzees and gorillas, which have stiff

Ar. ramidus just yet, awaiting more fossils. For now they are focusing wrists that absorb forces on their knuckles.

on the anatomy of Ardi and how she moved through the world. Her However, several researchers aren’t so sure about these inferences.

foot is primitive, with an opposable big toe like that used by living Some are skeptical that the crushed pelvis really shows the anatomical

apes to grasp branches. But the bases of the four other toe bones details needed to demonstrate bipedality. The pelvis is “suggestive” of

were oriented so that they reinforced the forefoot into a more rigid bipedality but not conclusive, says paleoanthropologist Carol Ward of the

lever as she pushed off. In contrast, the toes of a chimpanzee curve University of Missouri, Columbia. Also, Ar. ramidus “does not appear to

as flexibly as those in their hands, say Lovejoy and co-author have had its knee placed over the ankle, which means that when walk-

Bruce Latimer of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. ing bipedally, it would have had to shift its weight to the side,” she says.

Ar. ramidus “developed a pretty good bipedal foot while at the same Paleoanthropologist William Jungers of Stony Brook University in

time keeping an opposable first toe,” says Lovejoy. New York state is also not sure that the skeleton was bipedal. “Believe

The upper blades of Ardi’s pelvis are shorter and broader than in me, it’s a unique form of bipedalism,” he says. “The postcranium alone

apes. They would have lowered the trunk’s center of mass, so she could would not unequivocally signal hominin status, in my opinion.” Paleo-

balance on one leg at a time while walking, says Lovejoy. He also anthropologist Bernard Wood of George Washington University in

infers from the pelvis that her spine was long and curved like a Washington, D.C., agrees. Looking at the skeleton as a whole, he says,

human’s rather than short and stiff like a chimpanzee’s. These “I think the head is consistent with it being a hominin, … but the rest of

changes suggest to him that Ar. ramidus “has been bipedal for a very the body is much more questionable.”

long time.” All this underscores how difficult it may be to recognize and

Yet the lower pelvis is still quite large and primitive, similar to define bipedality in the earliest hominins as they began to shift from

African apes rather than hominins. Taken with the opposable big toe, trees to ground. One thing does seem clear, though: The absence of

and primitive traits in the hand and foot, this indicates that Ar. ramidus many specialized traits found in African apes suggests that our

didn’t walk like Lucy and was still spending a lot of time in the trees. ancestors never knuckle-walked.

But it wasn’t suspending its body beneath branches like African apes That throws a monkey wrench into a hypothesis about the last

or climbing vertically, says Lovejoy. Instead, it was a slow, careful common ancestor of living apes and humans. Ever since Darwin

www.sciencemag.org SCIENCE VOL 326 2 OCTOBER 2009 39

Published by AAAS

NEWSFOCUS Ardipithecus ramidus

Habitat for Humanity Past and present. Ardipithecus’s wood-

land was more like Kenya’s Kibwezi Forest

ARAMIS, ETHIOPIA—A long cairn of black stones (left) than Aramis today.

marks the spot where a skeleton of Ardipithecus

ramidus was found, its bones broken and scattered

on a barren hillside. Erected as a monument to an

ancient ancestor in the style of an Afar tribesman’s

grave, the cairn is a solitary marker in an almost

sterile zone, devoid of life except for a few spindly

acacia trees and piles of sifted sediment.

That’s because the Middle Awash research team

sucked up everything in sight at this spot, hunting

for every bit of fossil bone as well as clues to the

landscape 4.4 million years ago, when Ardipithe-

cus died here. “Literally, we crawled every square

inch of this locality,” recalls team co-leader Tim

White of the University of California, Berkeley.

“You crawl on your hands and knees, collecting

every piece of bone, every piece of wood, every

seed, every snail, every scrap. It was 100% collec-

tion.” The heaps of sediment are all that’s left

behind from that fossil-mining operation, which

yielded one of the most important fossils in human evolution (see main text, figs and other fruit when ripe, it didn’t consume as much fruit as chim-

p. 36), as well as thousands of clues to its ecology and environment. panzees do today.

The team collected more than 150,000 specimens of fossilized plants and This new evidence overwhelmingly refutes the once-favored but now

animals from nearby localities of the same age, from elephants to songbirds moribund hypothesis that upright-walking hominins arose in open grass-

to millipedes, including fossilized wood, pollen, snails, and larvae. “We have lands. “There’s so much good data here that people aren’t going to be able to

crates of bone splinters,” says White. question whether early hominins were living in woodlands,” says paleo-

A team of interdisciplinary researchers then used these fossils and anthropologist Andrew Hill of Yale University. “Savannas had nothing to do

thousands of geological and isotopic samples to reconstruct Ar. ramidus’s with upright walking.”

Pliocene world, as described in companion papers in this issue (see p. 66 Geological studies indicate that most of the fossils were buried within a

and 87). From these specimens, they conclude that Ardi lived in a wood- relatively short window of time, a few thousand to, at most, 100,000 years

land, climbing among hackberry, fig, and palm trees and coexisting with ago, says geologist and team co-leader Giday WoldeGabriel of the Los Alamos

monkeys, kudu antelopes, and peafowl. Doves and parrots flew overhead. National Laboratory in New Mexico. During that sliver of time, Aramis was not

All these creatures prefer woodlands, not the open, grassy terrain often a dense tropical rainforest with a thick canopy but a humid, cooler woodland.

conjured for our ancestors. The best modern analog is the Kibwezi Forest in Kenya, kept wet by ground-

The team suggests that Ar. ramidus was “more omnivorous” than chim- water, according to isotope expert Stanley Ambrose of the University of

panzees, based on the size, shape, and enamel distribution of its teeth. It Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. These woods have open stands of trees, some

probably supplemented woodland plants such as fruits, nuts, and tubers 20 meters high, that let the sun reach shrubs and grasses on the ground.

with the occasional insects, small mammals, or bird eggs. Carbon-isotope Judging from the remains of at least 36 Ardipithecus individuals found so

studies of teeth from five individuals show that Ar. ramidus ate mostly far at Aramis, this was prime feeding ground for a generalized early biped. “It

woodland, rather than grassland, plants. Although Ar. ramidus probably ate was the habitat they preferred,” says White. –A.G.

suggested in 1871 that our ancestors arose in Africa, researchers have note the many ways that Ar. ramidus differs from chimpanzees and

debated whether our forebears passed through a great-ape stage in gorillas, bolstering the argument that it was those apes that changed

which they looked like proto-chimpanzees (Science, 21 November the most from the primitive form.

1969, p. 953). This “troglodytian” model for early human behavior But the problem with a more “generalized model” of an arboreal

(named for the common chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes) suggests that ape is that “it is easier to say what it wasn’t than what it was,” says

the last common ancestor of the African apes and humans once had Ward. And if the last common ancestor, which according to genetic

CREDITS (LEFT TO RIGHT): TIM WHITE; ANN GIBBONS

short backs, arms adapted for swinging, and a pelvis and limbs studies lived 5 million to 7 million years ago, didn’t look like a

adapted for knuckle walking. Then our ancestors lost these traits, chimp, then chimpanzees and gorillas evolved their numerous simi-

while chimpanzees and gorillas kept them. But this view has been larities independently, after gorillas diverged from the chimp/human

uninformed by fossil evidence because there are almost no fossils of line. “I find [that] hard to believe,” says Pilbeam.

early chimpanzees and gorillas. As debate over the implications of Ar. ramidus begins, the one thing

Some researchers have thought that the ancient African ape bau- that all can agree on is that the new papers provide a wealth of data to

plan was more primitive, lately citing clues from fragmentary fossils frame the issues for years. “No matter what side of the arguments you

of apes that lived from 8 million to 18 million years ago. “There’s come down on, it’s going to be food for thought for generations of

been growing evidence from the Miocene apes that the common graduate students,” says Jungers. Or, as Walker says: “It would have

ancestor may have been more primitive,” says Ward. Now been very boring if it had looked half-chimp.”

Ar. ramidus strongly supports that notion. The authors repeatedly –ANN GIBBONS

40 2 OCTOBER 2009 VOL 326 SCIENCE www.sciencemag.org

Published by AAAS

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A New Kind of Ancestor:: Ardipithecus UnveiledDocument5 paginiA New Kind of Ancestor:: Ardipithecus UnveiledWara Tito RiosÎncă nu există evaluări

- First Steps: How Upright Walking Made Us HumanDe la EverandFirst Steps: How Upright Walking Made Us HumanEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (17)

- New Evidence: Only People Ever Walked Really Upright: Ing Individuals, Cells in The MembranousDocument2 paginiNew Evidence: Only People Ever Walked Really Upright: Ing Individuals, Cells in The MembranousArturoMerazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Louis Leaky AnthropologyDocument13 paginiLouis Leaky AnthropologyUpsc LectureÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Pithecanthropus Erectus: Studies on Ancestral Stock of MankindDe la EverandThe Pithecanthropus Erectus: Studies on Ancestral Stock of MankindÎncă nu există evaluări

- Early Man: Sean Pitman, MD March 2006Document73 paginiEarly Man: Sean Pitman, MD March 2006Dana GoanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evalution of MankindDocument2 paginiEvalution of MankindNEHALJAIN15Încă nu există evaluări

- Fossil Ida, The Missing Link?Document12 paginiFossil Ida, The Missing Link?ATLjazzmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Family Tree of ManDocument5 paginiThe Family Tree of ManElisha Gine AndalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- In Search of The First Hominids: Image Not Available For Online UseDocument6 paginiIn Search of The First Hominids: Image Not Available For Online UseDRagonrougeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Were There "Cavemen"?Document2 paginiWere There "Cavemen"?AlexPemaÎncă nu există evaluări

- أحفورة تعيد ترتيب التطور البشريDocument3 paginiأحفورة تعيد ترتيب التطور البشريAbu HashimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bushes and Ladders in Human Evolution-1Document5 paginiBushes and Ladders in Human Evolution-1KateTackettÎncă nu există evaluări

- 06-11-03: 160,000-Year-Old Skulls Are Oldest Anatomically Mode...Document5 pagini06-11-03: 160,000-Year-Old Skulls Are Oldest Anatomically Mode...johnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science 2009 Hanson 60 1Document4 paginiScience 2009 Hanson 60 1Krist Andrés Cabello ZúñigaÎncă nu există evaluări

- China's Dinos: FeaturesDocument1 paginăChina's Dinos: FeaturesHÀ ĐỖ VIẾTÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 1 - Early ManDocument69 paginiLecture 1 - Early ManAshish SolankiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Human Evolution - Ape To ManDocument6 paginiHuman Evolution - Ape To ManAngela Ann GraciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- No, Humans Didn't Evolve From The Ancestors of Living Apes - IEDocument6 paginiNo, Humans Didn't Evolve From The Ancestors of Living Apes - IEsimetrich@Încă nu există evaluări

- Making Monkeys Out of ManDocument3 paginiMaking Monkeys Out of ManpilesarÎncă nu există evaluări

- The People That Time Forgot: AstonishingDocument2 paginiThe People That Time Forgot: AstonishingSon PhamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Selection in Relation To SexDocument3 paginiSelection in Relation To SexclaudiasulfitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tridactyls Humanitys Constant Companionby Ed CasasDocument10 paginiTridactyls Humanitys Constant Companionby Ed CasasJulioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Physical: 55m Years Ago, ChinaDocument5 paginiPhysical: 55m Years Ago, ChinaRaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Descent SummaryDocument6 paginiThe Descent SummaryDr. Donald Perry83% (6)

- Ape To Man TranscriptDocument26 paginiApe To Man Transcriptteume reader accÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4-Ape Men-Mortenson-105 Eng CR 2194 v6Document105 pagini4-Ape Men-Mortenson-105 Eng CR 2194 v6scienceandapologeticsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Originof ManDocument110 paginiOriginof ManDr-Qussai ZuriegatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paleoanthropology: What Can Anthropologists Learn From Ancient Bones?Document2 paginiPaleoanthropology: What Can Anthropologists Learn From Ancient Bones?Patrick LawagueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aaa Quark Panels - Mar28-06Document19 paginiAaa Quark Panels - Mar28-06Henry B. May IV75% (4)

- Zoloogy Report BlindDocument8 paginiZoloogy Report BlindBlind BerwariÎncă nu există evaluări

- BECOMING HUMAN - Transcript 2Document14 paginiBECOMING HUMAN - Transcript 2Scar ShadowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ascent of The Mammals: Scientific American May 2016Document9 paginiAscent of The Mammals: Scientific American May 2016Rodrigo GRÎncă nu există evaluări

- Terrestrial Apes and Phylogenetic TreesDocument8 paginiTerrestrial Apes and Phylogenetic TreesVessel for the WindÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Offloading Ape - The Human Is The Beast That Automates - Aeon EssaysDocument9 paginiThe Offloading Ape - The Human Is The Beast That Automates - Aeon EssaysMartin MüllerÎncă nu există evaluări

- (2019 Article) Chris Stringer - The New Human StoryDocument2 pagini(2019 Article) Chris Stringer - The New Human StoryhioniamÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Book Shows That Fossil Record Supports Biblical View of Human OriginsDocument12 paginiNew Book Shows That Fossil Record Supports Biblical View of Human OriginsAndaraawoosIbnYusufÎncă nu există evaluări

- Timeline of Human Evolution: 1 Taxonomy of Homo SapiensDocument6 paginiTimeline of Human Evolution: 1 Taxonomy of Homo SapiensAndino Gonthäler100% (1)

- Documentary NotesDocument3 paginiDocumentary NotesMy Roses Are RosèÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ancestor or Adapiform? Darwinius and The Search For Our Early Primate AncestorsDocument9 paginiAncestor or Adapiform? Darwinius and The Search For Our Early Primate AncestorsNotaul NerradÎncă nu există evaluări

- Homo ErectusDocument27 paginiHomo ErectusPlanet CscÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Deniable Darwin David Berlinski PDFDocument12 paginiThe Deniable Darwin David Berlinski PDFrenatofigueiredo2005100% (1)

- The Littlest Human. Ebu Gogo, Homo FloresciensisDocument10 paginiThe Littlest Human. Ebu Gogo, Homo FloresciensisSalsaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ardi: How To Create A Science Myth and How To Debunk Evolutionary Propaganda - John FeliksDocument42 paginiArdi: How To Create A Science Myth and How To Debunk Evolutionary Propaganda - John FeliksE. ImperÎncă nu există evaluări

- DiscoveriesDocument3 paginiDiscoveriesPochengShihÎncă nu există evaluări

- Speech 4Document2 paginiSpeech 4api-577081322Încă nu există evaluări

- 2020 08 Dinosaur Skeleton Ready CloseupDocument3 pagini2020 08 Dinosaur Skeleton Ready CloseupLleiLleiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evolution: IndividualDocument2 paginiEvolution: IndividualIpshita PathakÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Study: Before DarwinDocument3 paginiHistory of Study: Before DarwinSanket PatilÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2014 David Pratt Human Origins - The Ape - Ancestry MythDocument96 pagini2014 David Pratt Human Origins - The Ape - Ancestry MythPelasgosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ucsp Reviewer Quiz 1Document8 paginiUcsp Reviewer Quiz 1koriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sykes, R. W. 2021 Shenaderthal. AEONDocument2 paginiSykes, R. W. 2021 Shenaderthal. AEONCarlos González LeónÎncă nu există evaluări

- Palaeoanthropology and Human Evolution: November 2016Document44 paginiPalaeoanthropology and Human Evolution: November 2016Stephany Rodrigues CarraraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Science Has Been Working in Order To Find AnswersDocument6 paginiScience Has Been Working in Order To Find Answersapi-219303558Încă nu există evaluări

- Ucsp FinalsDocument10 paginiUcsp FinalsMhaica GalagataÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ellenberger - The Mental Hospital and The Zoological GardenDocument18 paginiEllenberger - The Mental Hospital and The Zoological GardenChristina HallÎncă nu există evaluări

- Document 2Document2 paginiDocument 2Eagle HeartÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Draft Sequence of The Neandertal Genome (Sapiens/Neanderthal Interbreeding)Document14 paginiA Draft Sequence of The Neandertal Genome (Sapiens/Neanderthal Interbreeding)José Pedro GomesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Close Encounters of The Prehistoric Kind: OnlineDocument5 paginiClose Encounters of The Prehistoric Kind: Onlinejohnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- 723 (2010) Hernán A. Burbano,: Science Et AlDocument4 pagini723 (2010) Hernán A. Burbano,: Science Et Aljohnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cell, Vol. 90, 19-30, July 11, 1997, Copyright ©1997 byDocument12 paginiCell, Vol. 90, 19-30, July 11, 1997, Copyright ©1997 byjohnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neanader 2 PDFDocument5 paginiNeanader 2 PDFjohnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Cranium For The Earliest Europeans: Phylogenetic Position of The Hominid From Ceprano, ItalyDocument6 paginiA Cranium For The Earliest Europeans: Phylogenetic Position of The Hominid From Ceprano, Italyjohnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Neanader 2 PDFDocument5 paginiNeanader 2 PDFjohnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- American Journal of Physical Anthropology 138:90-100 (2009)Document11 paginiAmerican Journal of Physical Anthropology 138:90-100 (2009)johnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- The First Female Homo Erectus Pelvis, From Gona, Afar, EthiopiaDocument5 paginiThe First Female Homo Erectus Pelvis, From Gona, Afar, Ethiopiajohnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foraging of Homo Ergaster and Australopithecus Boisei in East African EnvironmentsDocument6 paginiForaging of Homo Ergaster and Australopithecus Boisei in East African Environmentsjohnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Mystery Ape From LonggupoDocument4 paginiThe Mystery Ape From Longgupojohnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Homo Erectus2Document2 paginiHomo Erectus2johnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- American Journal of Physical Anthropology 138:90-100 (2009)Document11 paginiAmerican Journal of Physical Anthropology 138:90-100 (2009)johnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Giants' in The Land: An Assessment of Gigantopithecus and MeganthropusDocument4 paginiGiants' in The Land: An Assessment of Gigantopithecus and Meganthropusjohnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Afar Ens IsDocument15 paginiAfar Ens Isjohnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Afar 222Document31 paginiAfar 222johnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aethiopicus 1Document3 paginiAethiopicus 1johnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- 06-11-03: 160,000-Year-Old Skulls Are Oldest Anatomically Mode...Document5 pagini06-11-03: 160,000-Year-Old Skulls Are Oldest Anatomically Mode...johnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Robustus 2Document5 paginiRobustus 2johnny cartinÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire - Volume IDe la EverandThe Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire - Volume IEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (78)

- Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the ModernDe la EverandTwelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the ModernEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (9)

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedDe la Everand1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (111)

- Strange Religion: How the First Christians Were Weird, Dangerous, and CompellingDe la EverandStrange Religion: How the First Christians Were Weird, Dangerous, and CompellingEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (3)

- The Ruin of the Roman Empire: A New HistoryDe la EverandThe Ruin of the Roman Empire: A New HistoryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gnosticism: The History and Legacy of the Mysterious Ancient ReligionDe la EverandGnosticism: The History and Legacy of the Mysterious Ancient ReligionEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (132)

- Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval EmpireDe la EverandByzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval EmpireEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (138)

- Giza: The Tesla Connection: Acoustical Science and the Harvesting of Clean EnergyDe la EverandGiza: The Tesla Connection: Acoustical Science and the Harvesting of Clean EnergyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Riddle of the Labyrinth: The Quest to Crack an Ancient CodeDe la EverandThe Riddle of the Labyrinth: The Quest to Crack an Ancient CodeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsDe la EverandThe Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (10)

- Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of TechnologyDe la EverandGods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of TechnologyEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (42)

- Strange Religion: How the First Christians Were Weird, Dangerous, and CompellingDe la EverandStrange Religion: How the First Christians Were Weird, Dangerous, and CompellingEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (3)

- Early Christianity and the First ChristiansDe la EverandEarly Christianity and the First ChristiansEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (19)

- Roman History 101: From Republic to EmpireDe la EverandRoman History 101: From Republic to EmpireEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (59)

- The Cambrian Period: The History and Legacy of the Start of Complex Life on EarthDe la EverandThe Cambrian Period: The History and Legacy of the Start of Complex Life on EarthEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (17)

- The book of Thoth: A Short Essay on the Tarot of the EgyptiansDe la EverandThe book of Thoth: A Short Essay on the Tarot of the EgyptiansEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (7)

- Ten Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to ConstantineDe la EverandTen Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to ConstantineEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (114)

- The Writing of the Gods: The Race to Decode the Rosetta StoneDe la EverandThe Writing of the Gods: The Race to Decode the Rosetta StoneEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (33)

- The Scythian Empire: Central Eurasia and the Birth of the Classical Age from Persia to ChinaDe la EverandThe Scythian Empire: Central Eurasia and the Birth of the Classical Age from Persia to ChinaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (6)

- Pandora's Jar: Women in the Greek MythsDe la EverandPandora's Jar: Women in the Greek MythsEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (256)

- Past Mistakes: How We Misinterpret History and Why it MattersDe la EverandPast Mistakes: How We Misinterpret History and Why it MattersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (14)

- Ancient Egyptian Magic: The Ultimate Guide to Gods, Goddesses, Divination, Amulets, Rituals, and Spells of Ancient EgyptDe la EverandAncient Egyptian Magic: The Ultimate Guide to Gods, Goddesses, Divination, Amulets, Rituals, and Spells of Ancient EgyptÎncă nu există evaluări

- Caligula: The Mad Emperor of RomeDe la EverandCaligula: The Mad Emperor of RomeEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (16)

- Ur: The History and Legacy of the Ancient Sumerian CapitalDe la EverandUr: The History and Legacy of the Ancient Sumerian CapitalEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (75)