Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Shapes and Shadows, Unveiling The Immigrant in Ali's Brick Lane

Încărcat de

Shakti BhagchandaniDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Shapes and Shadows, Unveiling The Immigrant in Ali's Brick Lane

Încărcat de

Shakti BhagchandaniDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Journal of Commonwealth

Literature

http://jcl.sagepub.com/

Shapes and Shadows: (Un)veiling the Immigrant in Monica Ali's Brick Lane Jane

Hiddleston

The Journal of Commonwealth Literature 2005 40: 57 DOI: 10.1177/0021989405050665

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://jcl.sagepub.com/content/40/1/57.citation

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for The Journal of Commonwealth Literature can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://jcl.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://jcl.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

Shapes and Shadows

Shapes and Shadows: (Un)veiling the Immigrant

in Monica Ali’s Brick Lane

Jane Hiddleston

University of Warwick, UK

Most of the flats that closed three sides of a square had net curtains and the life behind was all shapes and

shadows.1

Monica Ali’s Brick Lane burst into the public domain in the summer of 2003, generating both

enthusiastic critical acclaim and defensive anger. Praised by some for providing a much needed and

so far unprecedented portrait of the Bangladeshi community of London’s East End, the novel also

irritated some members of that community, who saw its portrayal of their lives as inaccurate and

derogatory. While some readers congratu- lated Ali for pulling back the curtains of the residences of

Tower Hamlets and depicting the injustices and dissatisfactions suffered by their inhabi- tants,

others were shocked by her boldness and offended by what they considered to be a gross

misrepresentation of Bengali culture in London. Included in Granta’s list of best young authors,

nominated for the US Award of the National Book Critics’ Circle, and short-listed for the Booker Prize,

Ali at the same time received a letter from the Greater Sylhet Development and Welfare council

condemning her depiction of Bangladeshis as backward and uneducated. This divided response to

Ali’s work reveals not only differences in readerly expectations and preconceptions regarding the

community in hand, but also a mire of uncertainties concerning the nature of literary representation,

in this particular case and more generally. This article will try to elucidate these uncertainties and

establish more clearly the nature and implications of Ali’s fictional experimentation in Brick Lane.

Both the responses cited above seem still to rely on some notion of literature as realist documen-

tation, but an alternative approach might focus instead on the difficulties of such a construction, on

the deceptive effects of the text’s rhetoric. The

Copyright © 2005 SAGE Publications www.sagepublications.com (London, Thousand Oaks, and New Delhi) Vol 40(1):57–72.

DOI: 10.1177/0021989405050665

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

58 Journal of Commonwealth Literature

novel at times draws attention to its own artifice, rather than purporting to provide straightforward

knowledge about a community unfamiliar to many readers. I want to examine the fraught

relationship between these readings, and the novel’s ambivalent call to the reader to interpret it on

two seemingly incompatible levels.

Ali’s novel to a certain extent sets itself up as a fresh look behind the closed doors of a segregated

community positioned at the centre of the British capital. Situated at the heart of London, side by

side with the financial centre of the city, the geographical area around Brick Lane is nevertheless

still conceived as a segregated space for the underprivi- leged. Although this segregation, this sense

of separation from the rest of society, means that it is increasingly perceived as a tourist attraction,

the area is still associated with stereotypes and myths of backwardness, delinquency and social

nonconformity. Sukhdev Sandhu’s review of Brick Lane in The London Review of Books traces some

of the history of this exclusion, noting that from as early as the eighteenth century the area has

been “a home for those who have been pushed out of their homes”.2 It housed Huguenot refugees

escaping French persecution, followed by East European Jews fleeing the pogroms in 1882, and

immi- grants from Bangladesh, Malta, Cyprus, the Caribbean and Somalia have been settling there

for over two hundred years.3 The Bangladeshi com- munity is currently by far the largest of these

groups, in part due to an influx of migrant workers who arrived from Dhaka in the 1960s in the hope

of finding work in textile factories. As the area has become more and more densely populated by

Bangladeshis, and as these seemingly transient migrants become a more settled and permanent

population, Brick Lane has also become a site of cultural conflict, and the number of racist attacks

has continued to grow. In addition, the area has seen a sharp rise in radical Islam, as the community

seeks its own identity in an attempt to fight back against discrimination and prejudice. Brick Lane

has more recently been affected by rising (exoticist) consumerism, but it is still associated with

social deprivation and poorly maintained housing estates, the inhabitants of which struggle to keep

up with the boom in capitalist culture infiltrating nearby streets. One part of Ali’s endeavour consists

in puncturing the myths that circulate around this annexed region, and she seeks at once to

humanize the apparent “underclass” of its residents and to expose the preconceptions informing

popular images of the unfamiliar stranger within.

From this point of view, the early evocation of “shapes and shadows” in Brick Lane announces Ali’s

daring attempt to give form to the hazy figures that flicker behind the surface of persistent

stereotypes and mis- conceptions. Ali boldly looks behind the walls of an area thought to be

populated by migrants, living at once within and outside British society,

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

Shapes and Shadows 59

and whose cultural practices continue to provoke bafflement and alarm. Discussion of the extent to

which the novel does actually reveal the sub- terranean existence of the real inhabitants of Brick

Lane, however, perhaps ignores the multi-layered nature of the project. First, the very notion of the

“shapes and shadows” draws attention to the haziness of the figures sketched by Ali. The image of

the net curtains plays on the notion of revelation or viewing, since they precisely allow the

inhabitant to see without being seen, and to frustrate the viewer’s desire to see. All we are offered

are murky silhouettes, and this partial veiling both provokes and eludes our quest for knowledge.

Furthermore, the use of this Platonic metaphor precisely reminds us that these characters are mere

forms or outlines, imperfect shadows that fail to reveal any under- lying truth. The evocation of

characters in these terms emphasizes the ways in which they are flawed, insubstantial imitations;

they are not real essences but forms carved out in language. Ali’s text is split, then, by this

contradiction between the hope for revelation on the one hand, and knowledge of the impossibility

of any complete unveiling on the other. She wants to illuminate a set of lives that have frequently

been forgotten and set aside, and the novel clearly seeks to uncover subjectivities that have so far

been deprived of a public voice. At the same time, however, the process of uncovering can itself be

read as a fictional construction created in discourse.

Secondly, Ali’s gesture of pulling back the curtains can be seen as the latest, modern version in a

series of endeavours to unveil the mysteries of an “Eastern” culture. Said’s Orientalism tracks the

history of this mythologization, locating across different forms of cultural production the Western

desire to know and appropriate the “Oriental” other.4 Said’s scope includes both the quest for

knowledge underpinning colonial occu- pation, and cultural narratives tracing the confusion of such

discoveries with subjective and aesthetic fantasies and desires. One common trope, moreover,

which resonates in particular with Ali, is that of unveiling, and of the penetration of interior space,

demonstrated perhaps most famously by Delacroix. The celebrated Femmes d’Alger dans leur

appartement was the product of the painter’s unorthodox penetration into the women’s quarters in

the house of one of the raïs during his travels in North Africa. First, the work is at once a revealing

depiction of a space conventionally shielded from the public gaze, and a somewhat fetishized

portrait of a subject already formed by Orientalist myths and stereotypes. It serves both to raise

questions about the nature of women’s existence cloistered in the harem, and to draw attention to

the traps of the representation process, as the painting plays on exoticist misrepresenta- tions and

the deceptive allure of the unfamiliar other. Secondly, however, the Delacroix painting then seems

to question its own endeavour, as the

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

60 Journal of Commonwealth Literature

women are portrayed as distant and dreamy, immersed in another world to which we cannot gain

full access. The penetration of women’s private, interior space does not necessarily result in

concrete discovery or knowl- edge.

Ali’s Brick Lane undertakes a similar project insofar as it invites us to discover the occluded lives of

the disenfranchized while also, para- doxically, showing the pervasive influence of myth in our

apprehension of “Eastern” cultures. On one level, the text can be seen as an attempt to exhibit the

life-styles and customs of a community traditionally either hidden from view or depicted according

to popular stereotypes, and Ali sets out to inform her readers by portraying the supporters of radical

Islam (as if) from the inside. To a certain extent, indeed like Delacroix, Ali wants to expose the

suffering of an oppressed segment of society, and she also humanizes and provides a context for a

form of Islamic cultural practice that has perhaps recently generated more suspicion and more

myth-making than any other custom. Nevertheless, while Ali wants to destroy certain myths, her

own text testifies to the impossibility of ridding one’s narrative of any mythologizing tendencies, and

her text displays the traps and lures of the representation process itself. The novel can be read as a

quest for knowledge, for unveiling, but it simultaneously betrays its own shaky status as a fictional

construction that masks as much as it reveals.

The text can in this way be read on two levels. The first of these would be concerned with its

success or failure as an accurate depiction of the people living behind the curtains of the flats

situated around Brick Lane. Since the novel does name that community and is quite explicit about

its aims to unveil it, its treatment as a “realist” text seems justifi- able. The second level, however,

would emphasize not the accuracy of the representation but the text’s own use of rhetoric and its

self- exposure as a discourse among many alternative, available versions or myths. As Nicholas

Harrison points out in Postcolonial Criticism, both approaches are determined by a history of reading

conventions and practices.5 Harrison’s conclusion to his explorations of Conrad, Camus, Chraibi and

Djebar stresses how literary texts do not intrinsically call for the use of just one set of interpretative

strategies, and the under- standing of literature as a process of formal experimentation belongs to a

very particular reading community. In the context of Ali’s work, however, since critics have already

assessed its efficacy as a portrait of a particular social phenomenon, it might now be illuminating to

fore- ground precisely those tropes and devices that announce its status as an artificial construct.

Existing readings, that conceive the text either as uniquely revelatory or as grossly

misrepresentative, can be counter- posed with this awareness of its implications as a literary

experiment, a

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

Shapes and Shadows 61

space where different discourses and rhetorical strategies are juxtaposed and realigned.

Brick Lane focuses on the trying life of its central character, Nazneen, born in Bangladesh, married

off at an early age to the overweight, frog- faced Chanu and shipped off to London to live with him in

Tower Hamlets. Ali concentrates in minute detail on the intricacies of Nazneen’s life, shut away from

the world with no freedom to make decisions of her own, and the narrative revels in its permeation

of the interior of the home, as well as in its dissection of her repressed longings. Agony and stupor

at the death of her first son are followed by the dull gnawing of routine domesticity, broken only by

seemingly ridiculous fan- tasies about ice-skating, learned from the competitions she avidly watches

on the television. Later on in the novel, Nazneen meets Karim, an activist for a local Islamic group,

whose seductive energy enthrals the housewife and leads her into an illicit affair. Through Nazneen’s

relation- ship with Karim, Ali explores the allure of the Islamic cause for charac- ters who desperately

need to reclaim a sense of self, and the text subtly juxtaposes depictions of hope with scattered

comments on racism, preju- dice, deprivation and social inequality. Noting also the conflicts between

Nazneen, Chanu and their daughters, the novel seems to want to provide insight into the frustration

and disorientation of a particular generation, caught between cultures and struggling to define itself

on its own terms, according to its own choices and beliefs.

Since the novel opens with the scene of Nazneen’s birth, one of the first issues Ali deals with is

cultural practice and custom back in Bangladesh. In a style at this point reminiscent of Rushdie’s

humorous exaggerations, Ali comically describes the mother Rupban’s surprise at the premature

arrival, and subsequent survival, of the tiny Nazneen, by infusing the narrative with fantastic

analogies and hints of unexplained customs or beliefs. Even in these opening pages, however, the

reader is forced to consider the implications and effects of common stereotypes or rhetorical tropes.

Ali already starts to plant images stemming from manufactured expectations regarding Bengali

culture and thought, and in so doing she immediately casts doubt over her own project of revel-

ation. One reviewer, Natasha Walter, complains in this context that Ali uses: “forgettable images.

Nazneen’s mother ‘had been ripening like a mango on a tree’. The midwife ‘was more desiccated

than an old coconut’”.6 From this point of view, Ali’s imagery seems somewhat stereotypical and

contrived, taking obvious, stock signifiers of an exotic Eastern culture and using them to caricature

the community of “foreign” characters evoked. Whether or not Ali intended to include such stereo-

types in order to provoke the reader, or indeed whether she absorbed them unwittingly and

reproduced them intact, remains in some sense

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

62 Journal of Commonwealth Literature

open to question in this early scene. Most importantly, however, what is compelling about the

passage is that in depicting Nazneen’s origins in Bangladesh, Ali is precisely drawing attention to

Western assumptions and stereotypes, or at least to the ways in which popular images serve to

organize and shape our perceptions of Asian culture. A further example might be when Hamid

greets the birth of a daughter, as opposed to a son, with resolute indifference before Ali cuts to an

evocation of curry smells, and here the use of such stock images again provokes us into interrogat-

ing our preconceptions as readers approaching Bangladesh from the outside. Ali does herself

pinpoint this shaky, mythical perception of Bangladesh, when she comments in an interview on the

detachment of migrant families from their countries of origin and their continued use of fantastical

imagery to enrich their knowledge of what they left behind: “home, because it could never be

reached, became mythical: Tagore’s golden Bengal, a teasing counterpoint to our drab northern

milltown lives”.7 In the novel, Chanu teaches his daughter to recite Tagore’s poem, hoping to

familiarize her with her origins, but Shahana’s disengagement and mistrust highlight the

contrivance of using such imagery to re- establish links between the second generation and the

original culture of their “roots”.

Ali’s portrayal of Nazneen’s sister Hasina, and the transcription of her letters from Bangladesh, has

aroused similar critical concern. Many critics who praise the rest of Ali’s narrative struggle to accept

Hasina’s letters as a convincing indication of the suffering experienced as a result of defying one’s

parents in favour of a “love marriage” in Bangladesh. Written in broken English, the letters convey

Hasina’s growing despair, as her husband becomes violent, her marriage falls apart and she is

forced to seek work in a factory, even as a prostitute, and as a maid. Yet the style of the letters

emphasizes Hasina’s naivety and vulnerability, and seems on one level to reinforce prevalent

assumptions regarding the relentless subordination of women in postcolonial Islamic societies.8

Despite her attempts to speak out against the restrictions of tradition, Hasina is por- trayed as

bewildered, faltering, desperate to please and unsure of how to take control of her fate. In one

extract, we witness her husband’s search for perfection in his wife and Hasina’s apparent,

uncomprehending acquiescence:

You know my husband tell me this. First moment he see me it the perfect moment in his whole and entire life.

This is how he say. In his whole and entire life. He like to live it again and he planning to make it come again as

an actual fact. He have me sit in bed and put my hair in certain way over one shoulder. Sheet is smooth at one

end and crumple at other. I must tilt my face so or so. But light is never right. I hold head too tight or too loose.

It hard for him not to get angry he trying to make something perfect.

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

Shapes and Shadows 63 Sometime he say my face have change and he tell me to change it back but

I soothe and he is quiet again.9

Passages such as this overstate Hasina’s pitiable condition, and the ten- tative, broken sentences

and grammatical confusion convey an imposs- ible helplessness. Moreover, many readers have

pointed out that both sisters speak Bengali, so it seems baffling that the letters should have been

written in this stilted, pidgin style, and the language only makes the letters seem “banal and

comic”.10 Hasina’s non-mastery of English unnecessarily overemphasizes her weakness, and adds a

certain con- trived drama to the conflict between the demanding Muslim husband and his wife. Even

worse, Pankaj Mishra in the New York Review of Books comments that “at times, Hasina sounds

more like a travel writer from England than an oppressed woman from Bangladesh, especially when

she reports on the rickshaws in Dhaka painted with the face of Britney Spears”.11 This criticism

directly allies Ali’s use of dialect with Western stereotypes rather crassly informing conceptions of

the confrontation between East and West.

Once again, these reservations towards the letters are valid, and Hasina’s character is undoubtedly

a little unsubtle in its collusion with Western preconceptions of women’s subjugation under Islam.

Since Ali’s text is a work of literature, however, and since at other times the author deliberately

undermines mythologized depictions of “the Eastern other”, it is worth considering not only the

“accuracy” of the letters but also their implications as a literary device. Indeed, perhaps Ali’s text

can be read not as a “faithful” transcript of any “exemplary” letter-writing but rather as a forum

where myths circulating around both cultures are exposed in order to provoke the reader. The stock

images of Hasina’s letters are themselves testimony to the pervasiveness of such stereotypes in

Bangladesh as well as in Britain, and their inclusion in a novel such as this forces us to consider the

difficulty of attempting to free any represen- tation of cultural identity from their influence.

Consciously or not, Ali draws our attention to the ongoing entrenchment of popular misconcep- tions

in both countries, and to the role of prejudice in reinforcing patterns of inequality and oppression.

She sets out to depict the mistreatment of women in Bangladesh, but she also displays prevalent

assumptions con- cerning their ability to understand and express their position. Further- more, the

halting style in which the extracts are written feeds the anglophone reader’s expectations that

Hasina should be somehow “foreign”, or unable to express herself using rational or argumentative

language. The clumsiness and incoherence of her letters signifies her situ- ation outside the

dominant paradigms of Englishness, and it connotes a cultural frontier lingering in the mind of the

reader.

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

64 Journal of Commonwealth Literature

Ali’s exploration of the “shapes and shadows” of Bengali culture and experience in this way consists

both in an unveiling of certain pervasive social and cultural structures and in a commentary on the

discourses informing our knowledge of those structures. Similarly, the author’s portrait of Nazneen’s

closeted existence in Tower Hamlets too raises the question of our deluded desire for unmediated

knowledge. On one level, Ali’s intricate examination of the details of Nazneen’s everyday life sets

out to traverse boundaries between public and private, and to provide the reader with knowledge

about the detailed customs of those ordinar- ily enclosed in their ghetto. The narrator elaborates

minutely on the material contents and physical attributes of the interior in an effort to convey the

intricacies of the scene behind the curtains. Sandhu judges the technique as “pointlessly accretive,

compendious”, and suggests that Ali is somewhat clumsy in her desire to describe each minute

detail of the flat’s unknown interior. Once again, however, another reading might emphasize how

the descriptions precisely draw our attention to the mechanics of revelation, of the deluded desire to

collect and accumulate noteworthy pieces of information.12 In one of the first scenes inside the flat,

for example, objects and decorations are precisely enumerated one by one:

There were three rugs: red and orange, green and purple, brown and blue. The carpet was yellow with a green

leaf design. One hundred per cent nylon and, Chanu said, very hard-wearing. The sofa and chairs were the

colour of dried cow dung, which was a practical colour. They had little sheaths of plastic on the headrests to

protect them from Chanu’s hair oil. There was a lot of furniture, more than Nazneen had seen in one room

before. Even if you took all the furniture in the compound, from every auntie and uncle’s ghar, it would not

match up to this one room. There was a low table with a glass centre and orange plastic legs, three little

wooden tables that stacked together, the big table they used for the evening meal, a bookcase, a corner

cupboard, a rack for newspapers, a trolley filled with files and folders, the sofa and armchairs, two footstools, six

dining chairs and a showcase. The walls were papered in yellow with brown squares and circles lining neatly up

and down. (p. 15)

The relentless piling up of details in this passage foregrounds the greedy quest for knowledge

subtending the attempt to enumerate and check the minutiae of the family’s existence. In a way

that recalls the detailed pro- fusion and ebullience of Balzac’s descriptions, or the eventual

eradication of any coherent image from Flaubert’s playful rhetorical experiments, the passage

finishes by reminding us of the ultimate meaninglessness of the disparate objects and decorations

piled up in front of our eyes. Both these apparently “realist” writers trouble their own processes of

representation by adding an excess of spurious detail that leads to the disintegration of

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

Shapes and Shadows 65

any coherent image. Equally, Ali traces the intricate modulations of Nazneen’s fleeting reactions to

her environment, noting for example how, after looking around the room and observing the flaws in

the flat’s décor: “she looked and she saw that she was trapped inside this body, inside this room,

inside this flat, inside this concrete slab of entombed humanity” (p. 61). In this example, the drive to

unveil the changing inner musings of her sequestered heroine results in a simple metaphor imposed

upon the character by the narrator, rather than in genuine insight into the inacces- sible world of the

immigrant woman’s psyche.

In the process of drawing the reader into Nazneen’s consciousness, Ali also plays with narrative

perspective and self-consciously explores the mechanics of such an intrusion. If on the one hand she

is seeking to reveal Nazneen’s inner thoughts and to display the suppressed effects of her seclusion,

Ali at the same time constantly shifts her perspective so as to raise the question of who speaks for

whom. In the passages elucidating Nazneen’s private reflections, the perspective often switches

from that of an external narrator to free indirect discourse, giving the impression that the character

speaks for herself. Crafted metaphors, for example, are juxtaposed with more direct, unmediated

reactions. In one passage, Ali describes Nazneen’s ill-defined dissatisfaction, and shifts from the

position of an observant narrator to an apparent transcription of the character’s desperate thoughts:

There was this shapeless, nameless thing that crawled across her shoulders and nested in her hair and poisoned

her lungs, that made her both restless and listless. What do you want with me? she asked it. What do you want?

it hissed back. She asked it to leave her alone but it would not. She pre- tended not to hear, but it got louder.

She made bargains with it. No more eating in the middle of the night. No more dreaming of ice, and blades, and

spangles. No more missed prayers. No more gossip. No more dis- respect to my husband. She offered all these

things for it to leave her. It listened quietly, and then burrowed deeper into her internal organs. (p. 83)

Here, if at the beginning of the passage the image of the shapeless burden is clearly a literary

construction formed by the narrator, later on it becomes merely the indistinct trigger for Nazneen’s

confused demands upon herself. The shorter exigencies – “no more eating . . .” and so on – seem

more concrete manifestations of the character’s unease, neverthe- less introduced in the form of a

created metaphor. In flickering in and out of Nazneen’s thoughts in this way, Ali tentatively

endeavours to “give voice” to her character, but she also uses her narrator as a frame. She

oscillates between perspectives and registers as if to uncover the different layers of the text’s

construction and to dramatize the unsettled relation- ship between the character and the narrative

that gives her form.

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

66 Journal of Commonwealth Literature

One of the most provocative aspects of Ali’s endeavour to uncover both the secrets of Nazneen’s

existence and the mechanics of its representation is her treatment of her relationship with radical

Islam. In tracing Nazneen’s growing interest in Karim and the Bengal Tigers, Ali succeeds in showing

how the religion itself is always apprehended through symbols, signs and stereotypes, whose

underlying substance is difficult to identify. First, the novel confronts myths associating radical Islam

with irrational fanaticism, and treats its proponents also as suffer- ing individuals with a plethora of

reasons for seeking a specific cause. Islam is currently seen by many in the West as a threat to

civilization and democracy, and therefore as an incomprehensible and foreign other encapsulating

all that Western society is not.13 Certainly the religion as a whole has mistakenly been aligned with

terrorism, and widespread ignor- ance has given rise to popular images of a fixed set of tenets,

promoting oppression and violence, at odds with principles of freedom and equality. Ali confronts

these stereotypes, and presents the characters’ anger not as a mythical, incomprehensible hatred of

the West but as a desperate reaction to their unequal status in that society. The Islamic group’s

meetings, for example, are hardly driven by the promotion of a focused set of beliefs but comprise a

series of chaotic ramblings, as different char- acters express varying ideas regarding the (shaky)

future of the organiz- ation. The motives of the speakers seem to be less a resistance to

“democracy” than the affirmation of some form of Muslim presence in a society that fails to

recognize their rights. Debates about the attacks on the World Trade Center, or sanctions in Iraq,

incite controversy and con- fusion rather than agreement for concrete action, and the participants

express a general sense of injustice through contradictory arguments. This presentation of the

evolution of the radical Islamist cause as an amalgamation of frustrations contradicts existing

judgements that condemn those apparently inimical to democracy as a principle. Notably, and this

is an argument also advocated in S. Sayyid’s analysis of A Funda- mental Fear, it is Western

hegemony and the marginalization of other cultures, rather than modernity itself, that sparks the

anger of the Islamist campaigners.14

For Nazneen, moreover, the return to Islam is neither a political nor a religious move but a symbol of

reassurance or hope. Early on in the novel, Islam seems significant for her not because of the

meaning of its tenets, nor because of its antipathy for Western society, but because it is a structure

that provides her with stability. Islam is a form or a signifier, connoting identity and certainty. When

apprehensive before Dr Azad comes for dinner, for example, Nazneen takes the Qu’ran down from

its shelf to remind herself of God’s watchful presence, until “the words calmed her stomach and she

was pleased. Even Dr Azad was nothing as

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

Shapes and Shadows 67

to God. To God belongs all that the heavens and the earth contain” (p. 14). Here, the words

themselves comfort Nazneen, their rhythms offer solace as much or indeed more than their content.

Shortly after this moment, Ali notes that Nazneen does not always understand the words she recites,

but their echo itself resonates with soothing associations. She knows Islam through the sounds of its

signifiers rather than through its underlying truths.

As the novel progresses, the nature of Nazneen’s recourse to Islam changes, yet form continues to

take precedence over content. Evidently, her interest in the activist group, the Bengal Tigers, is

bound up with her fascination for Karim, its inspired leader. But in describing Nazneen’s increasing

attraction to the religion and the man, Ali continues to draw the reader’s attention to the symbols

and signs that structure her per- ception of both. After her first attendance at a meeting, Nazneen

begins to understand her indistinct and gnawing sense of unease in terms of religious oppression:

“she mistook the sad weight of longing in her stomach for sorrow, and she read in the night of

occupiers and orphans, of Intifada and Hamas” (p. 201). The Islamic cause gives shape and struc-

ture to the hazy dissatisfaction of her day-to-day existence. Similarly, Karim’s fervour seduces her

not because of the inherent substance of his words but because he exudes confidence and hope.

When listening to him pray, she attends less to the content of his speech than to his calm self-

assurance and the accompanying poise of his bodily movements (“in prayer he does not falter,

thought Nazneen. And she pleaded with herself to keep fast to the words” [p. 193]). Ali’s

descriptions of Karim, at times in free indirect discourse from the point of view of Nazneen, similarly

pick out symbolic details, such as his dress, his pose, the ways in which he chooses to present

himself, in order further to emphasize the signifi- cance of form. Charting in detail his jeans and

trainers, and later his switch to a panjabi-pyjama and a skullcap, Ali underlines the ways in which his

identity, and Nazneen’s interpretation of it, rely on these surface signifiers. Ali’s investigation of

radical Islam in London recalls Hanif Kureishi’s Black Album and Zadie Smith’s White Teeth, but the

concentration on visual and rhetorical details, and Nazneen’s delectation of these, adds this formal

nuance to Shahid or Millat’s social and political questioning in the former novels.

Traces and signs of the distorting effects of the representation process unsettle depictions of both

resurgent Islamism and the intimate relation- ship between Nazneen and Karim. The novel at times

seeks to rescue its characters from overdetermination by entrenched stereotypes, but it also shows

how representations will persist in shaping our aspirations and desires. In warning her readers not to

misread Islam simply as an evil attack on Western democracy, Ali also reminds us that the visions of

the

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

68 Journal of Commonwealth Literature

religion’s followers are equally informed by created images and symbols. Nazneen’s journey, then, is

perhaps one of progress towards a realization of this process. Having summoned the courage to

defy her husband, and refusing to accompany him back to Bangladesh, she also finally distances

herself from Karim and her former perception of him, and she admits: “I wasn’t me, and you weren’t

you. From the very beginning to the very end, we didn’t see things. What we did – we made each

other up” (p. 380). Her relationship with Karim in this sense relied on an image she had fabricated, a

constructed simulacrum, rather than on any (impossible) understanding of his substance.

Concomitantly, Karim created her char- acter as “an idea of home. An idea of himself that he found

in her”, and both lovers reshaped the other to suit his or her own private needs. While avoiding

these processes may well be impossible, and while the charac- ters’ desires are as a result no less

urgent, Ali purposefully exhibits the traps and lures of representation even in their apprehension of

one another. In searching for a cause, a symbol of future certainty and stability, Nazneen learns

instead about the constructed, artificial nature of such symbols.

While Ali’s novel offers a subtle indication of the myths circulating around our knowledge of

Bangladesh, of Islam, and indeed of her char- acters’ own personal desires, the structure of

contemporary racist thinking constitutes the most overt target and provides a more cutting political

context for the novel. It has been noted that Brick Lane spends surprisingly little time examining

racial hatred in London’s East End. Sandhu’s aforementioned lengthy review comments that while

Ali’s text displays the chaotic factionalism of resurgent Islam, the novel has dis- appointingly little to

say about the campaign of violence and intimidation against the Bangladeshis of Brick Lane. Closer

attention to Ali’s work does, however, reveal that an awareness of the rhetoric informing per-

ceptions of Bangladeshi immigrants and their position in British society clearly structures the

characters’ mental world. While Ali certainly refrains from cataloguing racist attacks, she does

demonstrate how popular misconceptions drive the broader political consciousness of the host

society and affect immigrants’ lives. It is through this analysis of common images, terms and

buzzwords that Ali critiques the racist environment in which her characters live.

One important example of Ali’s denunciation of racist rhetoric can be found in her references to the

media. It is through the television that the characters find out about the Muslim riots in Oldham, and

in describing such images, Ali focuses on the movement of the camera, its choice of different

settings, more than on the events themselves. The way in which the riots are reconstructed by the

moving image is as significant in fuelling stereotypes as the violence itself. A further example occurs

at the

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

Shapes and Shadows 69

end of the novel, when local politicians and councillors tour the estate, followed by uncertain and

directionless television crews looking for a drugs scandal:

Television crews came in the afternoon. There was nothing to film, so they filmed each other. They returned

after dark and filmed the boys riding around in cars. They found the disused flats where the addicts gathered to

socialize with their addictions, and filmed the grotty mattresses and the bits of silver foil. It was a sensation. It

was on the local news. (p. 406)

In this passage, Ali notes how the cameramen initially find nothing to feed their suspicions, but

continue to seek evidence of poverty and delinquency until their expectations are fulfilled. Once

again, the photo- graphed images both create and prop up social and racial prejudices. Lastly, Ali

intermittently picks up on the hypocrisy and artifice of the terms informing debates on immigration,

such as “integration”, “assimi- lation”, “culture and religion” as opposed to “race” (p. 198). The sign,

in English and Bengali, warning “Vandals will be prosecuted” is also exposed as “pure rhetoric” (p.

194). Political debate, as well as social misperception, conceals an inadequate understanding of the

immigrant community at stake.

This reading of Brick Lane as an arena for the exposure of a variety of rhetorical figures and tropes

defines the work’s status as a literary experiment. Ali’s work of fiction exposes the workings of some

of the skewed discourses and images created by both British and Muslim com- munities about

themselves. On the one hand, though this is rarely made explicit in the novel, Ali reacts against the

traditional Muslim belief in the unmediated truth of the Qu’ran by exposing the rhetorical structures

shaping our understanding of Islam, and also of society, East and West, self and other. Radical

Muslims believe that the word of God is uncre- ated; literature and its exploration of multiple layers

and possibilities becomes an object of suspicion that poses a threat to this purity. Hanif Kureishi

pinpoints this distaste through the character Riaz, in The Black Album, who exhorts: “all fiction is, by

its very nature, a form of lying – a perversion of truth”.15 Furthermore, the furore generated by

Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses testifies even more disturbingly to the Islamic mistrust of literary

experimentation, since it was evidently Rushdie’s depiction of the religion as subject to endless

reinterpretation and rewriting that offended Muslim readers. The Satanic Verses explored how texts

offer a subjective slant, a constructed vision, rather than pure truth. Rushdie’s defence of his novel

in turn took the form of a renewed call for the intrin- sic value of literary experimentation, for an

understanding of the mediated nature of all discourses: “the novel has always been about the way

in which different languages quarrel, and about the shifting relations

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

70 Journal of Commonwealth Literature

between them, which are relations of power”.16 Tying in with the work of Kureishi and Rushdie, Ali

too displays the constructed nature of all narratives in a challenge to any apparent demand for

truth. Her literary text foregrounds the role of artifice in shaping our understandings of religion and

cultural practice.

Even more notably, Ali challenges not only any tendency to mistake discourse for truth, but also

those literary critical assumptions that ally the author too closely with the community she seems to

represent in her work. The text subverts not only the search for religious truth, but also the demand

for a stable authorial figure painting the portrait of a com- munity of which she is unequivocally a

part. When approaching texts in particular by writers who do not belong to the traditional national

canon, readers perhaps rather too frequently take that author as a spokesperson for the “minority”

group to which they seem to belong and read the work as a testimony to the experiences of that

group. Such critical moves again assume that literature is necessarily realist, and they also contrive

an impossibly seamless relationship between author and textual construc- tion. As I suggested, this

tendency is perhaps particularly notable in the context of “minority literatures”, as, according to

Nicholas Harrison, “it is indeed ‘members’ of minority groups who are most liable to be read as

representative, that is, liable to stereotyping, and who find themselves unable to act as individuals

to the extent that their every action may be taken as typical of the type to which they find

themselves assigned”.17 Tying in with this, many critics of Ali’s Brick Lane have similarly been too

keen to define the author as a member of the community she depicts. On the other hand, other

readers maintain this sense of a direct link between author and textual world, but criticize Ali

because she herself has not shared the experiences of her heroine Nazneen.

Ali herself, however, reacts against what she terms “the tyranny of representation”, a phrase

inherited from C.L.R James, meaning “that when I speak, my brown skin is the dominant signifier”.18

Instead she stresses her own shady, marginal relationship with her text. She claims neither to write

as a Bangladeshi woman living in London’s East End (she lives in South London in any case), nor as

a distant observer, but from the periphery, occupying no fixed or specified position. Recalling once

more the metaphor of the “shapes and shadows”, Ali asserts that she stands “neither behind a

closed door nor in the thick of things, but rather in the shadow of the doorway”. She is an uncertain

and indistinct figure who tries not to voice her own experiences but to allow the text to speak for

itself. Her assumption of an uneasy position in the peripheral shadows of the text suggests that she

wants to efface herself behind the different discourses she puts into play. She has no determined

argument, no personal hold upon the work, but uses the space of fiction to exhibit and perform a

series of

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

Shapes and Shadows 71

culturally and rhetorically produced figures. Furthermore, in effacing herself in this way, Ali is placing

the reader in an active position and forcing her to reflect on her own desires in relation to the text,

her desire for knowledge and insight, and her search for political or cultural critique.

Finally, it may seem surprising that a text that can justifiably be taken as a highly perceptive and

readable commentary on an under- represented community also unsettles its representational goals

by foregrounding its own artifice. Since the work has generated some controversy, however,

attention to its rhetorical strategies helps to elaborate its rather more complex relationship with its

social setting and its multi-layered construction as a fictional text. This emphasis on form and

rhetoric does not result in the dissociation of the work from any notion of an actual social world.

Brick Lane, in its exploration of discur- sive structures, is not entirely abstracted from the real Brick

Lane, and it does seek to offer insight into the lives of an existing group of immi- grants in the East

End. Nevertheless, parts of the novel draw attention to its very mediated position in relation to

those immigrants, and careful reading can bring out the illusions that structure our perception of the

unfamiliar other. From this point of view, the reader finishes less with an increased knowledge of the

experiences of an unfamiliar section of the British population than with a sense of unease towards

the sorts of discourse used to construct such knowledge. The novel is thus not a testi- mony offering

reliable information but a linguistic operation, and it forces us to reflect on the difficulties of

accessing its referent in an unmediated way. Its sketched outlines trace “shapes and shadows”, pro-

visional forms, rather than determinate individuals or incontrovertible truths.

NOTES

1 Monica Ali, Brick Lane. London: Doubleday, 2003, p. 12. All subsequent references to the text are to this

edition.

2 See Sukhdav Sandhu, “Come Hungry, Leave Edgy”, London Review of Books, 9 October 2003,

http://www.lrb.co.uk/v25/n19/sand/01_.html.

3 For more background, see Charles Husband, “The Political Context of Muslim Communities’ Participation in

British Society”, Muslims in Europe, ed. Bernard Lewis and Dominique Schnapper, London and New York: Pinter,

1994, pp. 79–97.

4 Edward Said, Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient, Harmonds- worth: Penguin, 1978.

5 See Nicholas Harrison, Postcolonial Criticism: History, Theory and the Work of Fiction, Cambridge: Polity,

2003.

6 Natasha Walter, “Citrus Scent of Inexorable Desire”, The Guardian, 14 June 2003,

http://books.guardian.co.uk/review/story/0,12084,975714,00.html.

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

72 Journal of Commonwealth Literature

7 See Monica Ali, “Where I’m Coming From”, http://www.powells.com/from theauthor/ali.html.

8 Critics such as Chandra Talpade Mohanty have examined this phenomenon, whereby well-meaning

Western feminists equate Islam with oppression, and sexual segregation and the control of women are seen as

universal problems in countries such as India, Pakistan, Egypt, etc. Mohanty points out the risk that “a large

number of different, fragmented examples from a variety of countries also add up to a universal fact”. See

“Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses”, in Colonial Discourse and Postcolonial

Theory: A Reader, ed. Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman, Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1993:

196–220 (p. 209). More recently, Sangeeta Ray has examined the mythologization precisely of Indian women in

En-Gendering India: Woman and Nation in Colonial and Postcolonial Narrative, Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2000.

9 Monica Ali, Brick Lane, p. 143. 10 This is Sukhdav Sandhu’s description. 11 See Pankaj Mishra,

“Enigmas of Arrival”, The New York Review of Books,

18 December 2003, pp. 42–3 (p. 42). 12 Again, this is Sandhu’s evaluation. 13 For more on this, see

Edward Said, Covering Islam: How the Media and

Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World, London: Vintage, 1997. This perception of a division

between Islam and the West has become increasingly stark since the publication of Said’s study.

14 See S. Sayyid, A Fundamental Fear: Eurocentrism and the Emergence of Islamism, London and New York:

Zed Books, 1997.

15 Hanif Kureishi, The Black Album, London: Faber, 1995, p. 182. 16 Salman Rushdie, “Is Nothing Sacred?”,

Imaginary Homelands: Essays and

Criticism 1981–1991, London: Granta, 1991, pp. 415–29, p. 420. 17 Nicholas Harrison, Postcolonial Criticism,

p. 100. 18 Monica Ali, “Where I’m Coming From”.

Downloaded from jcl.sagepub.com by guest on December 29, 2010

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- 2Document6 pagini2angels_devilsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dirt in Victorian Literature ADocument4 paginiDirt in Victorian Literature ARashini D SelvasegaranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Walking Surviving in The Foreign Land Reconsidering Jamaica Kincaidgçös LucyDocument16 paginiWalking Surviving in The Foreign Land Reconsidering Jamaica Kincaidgçös LucyGlobal Research and Development ServicesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Examining The Clash of Mass and Elite Culture in The Lady of ShalottDocument5 paginiExamining The Clash of Mass and Elite Culture in The Lady of ShalottSitong LiuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Female Role in Midaq AlleyDocument54 paginiFemale Role in Midaq Alleymaikel hajjarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bull, M. - Cultures of CapitalDocument19 paginiBull, M. - Cultures of CapitalkanebriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Writing RefugeeDocument11 paginiWriting RefugeeClara Willemsens100% (1)

- Luis E. Carranza - Le Corbusier and The Problems of RepresentationDocument13 paginiLuis E. Carranza - Le Corbusier and The Problems of Representationchns3Încă nu există evaluări

- Lee, Pamela M. - Forgetting The Art World (Introduction)Document45 paginiLee, Pamela M. - Forgetting The Art World (Introduction)Ivan Flores Arancibia100% (1)

- Bhabha (1992) The World and The HomeDocument14 paginiBhabha (1992) The World and The Homewhytheory100% (1)

- 2018-JILANI-How To Decolonize A MuseumDocument7 pagini2018-JILANI-How To Decolonize A MuseumMaura ReillyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural Criticism and Wuthering HeightsDocument4 paginiCultural Criticism and Wuthering HeightsIoana FarcasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Raymond Williams: Hugh Ortega Breton Posted 3 April 2007Document4 paginiRaymond Williams: Hugh Ortega Breton Posted 3 April 2007Abdullah Abdul HameedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Postcolonial Theory and CriticismDocument14 paginiPostcolonial Theory and CriticismSo FienÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bloody BodilyDocument22 paginiBloody Bodilygomezin88Încă nu există evaluări

- Claudette Lauzon, OCAD University: and Object of Critical Analysis of Embedded Social Structures ofDocument16 paginiClaudette Lauzon, OCAD University: and Object of Critical Analysis of Embedded Social Structures ofMirtes OliveiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2 Between Roots and Routes 2Document5 pagini2 Between Roots and Routes 2Lina BerradaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Writing Refugee in The Era of Displacement: Re Ections On PoetryDocument12 paginiWriting Refugee in The Era of Displacement: Re Ections On PoetryBen Rhit NadiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Frieze Magazine - Archive - The Other SideDocument5 paginiFrieze Magazine - Archive - The Other SideKenneth HeyneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Le Corbusier and The Problems of RepresentationDocument13 paginiLe Corbusier and The Problems of RepresentationSilina MariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BESKOVA WebDocument27 paginiBESKOVA WebĐặng Hoàng Mỹ AnhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cambridge University Press, Society For Historians of The Gilded Age & Progressive Era The Journal of The Gilded Age and Progressive EraDocument4 paginiCambridge University Press, Society For Historians of The Gilded Age & Progressive Era The Journal of The Gilded Age and Progressive EraJosh GatusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Onetti Baldi 676325 - 923102399 PDFDocument10 paginiOnetti Baldi 676325 - 923102399 PDFTeresaPorzecanskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cross CulturalismDocument16 paginiCross CulturalismDiablaÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Study of Cross-Culturalism in Derek Walcott's "Ti-Jean and His Brothers"Document17 paginiA Study of Cross-Culturalism in Derek Walcott's "Ti-Jean and His Brothers"annessa dasÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Origins and Relevance of Postcolonialism in Contemporary Art From An African PerspectiveDocument49 paginiThe Origins and Relevance of Postcolonialism in Contemporary Art From An African PerspectiveDenzel TayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Importance of Reading ClassicsDocument2 paginiImportance of Reading ClassicsKahloon Tham100% (1)

- Dissertation Final DraftDocument8 paginiDissertation Final DraftMovie DownloadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cunningham - Houses in Between - Navigating Suburbia in Late Victorian WritingDocument14 paginiCunningham - Houses in Between - Navigating Suburbia in Late Victorian Writingjudit456Încă nu există evaluări

- Postocoloniality at Large. Sklodowska Benitez RojoDocument32 paginiPostocoloniality at Large. Sklodowska Benitez RojoZnikomekÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stott (2012)Document24 paginiStott (2012)Yossa PratamaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Queer Gothic Literature and CultureDocument15 paginiQueer Gothic Literature and Cultureradioactive.greenmonsterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Manikins Wobbling Towards Dismemberment Art and Religion - State of The UnionDocument5 paginiManikins Wobbling Towards Dismemberment Art and Religion - State of The UnionAlex Arango ValenciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Dialectics of Cultural Criticism 199Document17 paginiThe Dialectics of Cultural Criticism 199najib yakoubiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Conscience of The Eye - Richard SennettDocument2.074 paginiThe Conscience of The Eye - Richard SennettPatrícia da Veiga20% (5)

- Marc Augé - in The Metro (2002)Document145 paginiMarc Augé - in The Metro (2002)Habib H Msallem100% (1)

- Bataille Architecture 1929Document3 paginiBataille Architecture 1929rdamico23Încă nu există evaluări

- Shanghai Dancers: Gender, Coloniality and The Modern Girl: Research OnlineDocument17 paginiShanghai Dancers: Gender, Coloniality and The Modern Girl: Research Onlineロベルト マチャード100% (1)

- Forum Navale 74 Tomas NilsonDocument42 paginiForum Navale 74 Tomas NilsonbemoosishÎncă nu există evaluări

- Debord 1997 ADocument5 paginiDebord 1997 AalexhwangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brown - Bakhtin, Coin Street and NeighbourlinessDocument14 paginiBrown - Bakhtin, Coin Street and NeighbourlinessallidaniellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Threatening The Victorian Empire: Colonialism and WomanhoodDocument11 paginiThreatening The Victorian Empire: Colonialism and WomanhoodjulsanroÎncă nu există evaluări

- CityScope The Cinema and The CityDocument12 paginiCityScope The Cinema and The CityAmal HashimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gullivers Travels and IronyDocument6 paginiGullivers Travels and IronyFrank MweneÎncă nu există evaluări

- 15 - Alina Popa - Post-Colonialism in Shakespearean Work PDFDocument5 pagini15 - Alina Popa - Post-Colonialism in Shakespearean Work PDFHaji DocÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tale of Two Cities - Tashkent and Calcutta in The Literary ImaginationDocument18 paginiTale of Two Cities - Tashkent and Calcutta in The Literary ImaginationAnil ChaudharyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dadabhoy Public Humanities SubmissionDocument7 paginiDadabhoy Public Humanities SubmissionAmbereen DadabhoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enwezor & Oguibe. Lagos: 1955-1970Document24 paginiEnwezor & Oguibe. Lagos: 1955-1970ngamso100% (1)

- On The Trail of Lygia Clark: Critique D'artDocument4 paginiOn The Trail of Lygia Clark: Critique D'artVictoria NarroÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 4 Modernity and The Spaces of Femininity: Modern Life: Paris in The Art Manet and His Followers, by T. J. Clark, 3Document23 pagini1 4 Modernity and The Spaces of Femininity: Modern Life: Paris in The Art Manet and His Followers, by T. J. Clark, 3Laura Adams DavidsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dandy ComisarDocument29 paginiDandy ComisarAncuta IlieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Joyce's Ghosts: Ireland, Modernism, and MemoryDe la EverandJoyce's Ghosts: Ireland, Modernism, and MemoryEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1)

- 466 1415 1 PBDocument8 pagini466 1415 1 PBju1976Încă nu există evaluări

- Texts and EmpireDocument27 paginiTexts and EmpireSiesmicÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Thousand Kitchen TablesDocument4 paginiA Thousand Kitchen TableskollectivÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bohls - Critique of Empire in FrankensteinDocument13 paginiBohls - Critique of Empire in FrankensteinLuis GarcíaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 17 - Minodora Otilia Simion - Modernism and Virginia Woolf S Novel Mrs DallowayDocument5 pagini17 - Minodora Otilia Simion - Modernism and Virginia Woolf S Novel Mrs DallowayarabellamariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MUNGA (Team Responses)Document2 paginiMUNGA (Team Responses)Abdul MoizÎncă nu există evaluări

- Charles Spurgeon Scriptural IndexDocument59 paginiCharles Spurgeon Scriptural IndexjohndagheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Labyrinth Playbook 2010Document24 paginiLabyrinth Playbook 2010Paul LaubacherÎncă nu există evaluări

- Women and Religion 2nd EssayDocument5 paginiWomen and Religion 2nd EssayAnna Katherina LeonardÎncă nu există evaluări

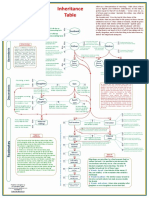

- Table of Islamic Inheritance PDFDocument1 paginăTable of Islamic Inheritance PDFSuru Suresh25% (4)

- NullDocument4 paginiNullURWA AKBARÎncă nu există evaluări

- 40 Ahaadith On MusicDocument9 pagini40 Ahaadith On MusictorentdownloadsÎncă nu există evaluări

- LochistDocument1 paginăLochistJherome BonaventeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Structure and Functions ofDocument234 paginiThe Structure and Functions ofMai FalakyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Features and Developments of Architectur PDFDocument5 paginiFeatures and Developments of Architectur PDFsundas waqarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Political Alliances & Movements in PAKISTANDocument258 paginiPolitical Alliances & Movements in PAKISTANdeedoo100% (1)

- My Brother, My Rival - How Can - Eve RabiDocument169 paginiMy Brother, My Rival - How Can - Eve RabiblondinableÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unofficial: Institute of Business Management (Iobm) Summer 2012 ScheduleDocument13 paginiUnofficial: Institute of Business Management (Iobm) Summer 2012 ScheduleMuhammad AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- HTF211 - Ch8 - Food Safety Regulations and Standards in Malaysia PDFDocument17 paginiHTF211 - Ch8 - Food Safety Regulations and Standards in Malaysia PDFhuant as ajkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ghalib Ke KhatDocument42 paginiGhalib Ke KhatSahil BhasinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Galool Maagazine Issue February 2013Document32 paginiGalool Maagazine Issue February 2013Majalada GaloolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kelab T2 2016Document9 paginiKelab T2 2016Fatin Nadia FadzilÎncă nu există evaluări

- SVG DhakaDocument108 paginiSVG Dhakasm shakhawat100% (3)

- Zehni Irtidaad - Intellectual Apostasy: Gauge of ImaanDocument4 paginiZehni Irtidaad - Intellectual Apostasy: Gauge of Imaanabdulrehman786Încă nu există evaluări

- Shah Bano Case and The Ensuing LegislationDocument3 paginiShah Bano Case and The Ensuing LegislationKirti sehgalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Architecture of Nagpur TemplesDocument18 paginiArchitecture of Nagpur TemplesSrishti DokrasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Roster Cuti Staf Tmu Site Berau Juni 23Document1 paginăRoster Cuti Staf Tmu Site Berau Juni 23Didit Beny PamujiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apartheid & IsraelDocument5 paginiApartheid & Israelapi-3844499Încă nu există evaluări

- Quranic Diagrammatic Overviews PDFDocument124 paginiQuranic Diagrammatic Overviews PDFMahmood AlyÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Revelation To Interpretation, Nasr Hamid Abu Zayd and The Literary Study of The Quran (Navid Kermani)Document24 paginiFrom Revelation To Interpretation, Nasr Hamid Abu Zayd and The Literary Study of The Quran (Navid Kermani)Adriana EsquivelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apj Abdul KalamDocument2 paginiApj Abdul KalamSuhana SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Araling Panlipunan Test Questions SampleDocument3 paginiAraling Panlipunan Test Questions SampleminaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ICIEF 2016 Programme Book 11th ICIEFDocument124 paginiICIEF 2016 Programme Book 11th ICIEFKhairunnisa Musari100% (1)

- Al-Madinah Munawwarah Its Names and Its Ancient HistoryDocument3 paginiAl-Madinah Munawwarah Its Names and Its Ancient HistoryShaikh Tanzim Akhtar100% (1)

- Format Nilai Raport MatematikaDocument49 paginiFormat Nilai Raport MatematikaMunib TahtaÎncă nu există evaluări