Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

On The Garifuna People of Honduras

Încărcat de

Inti Martínez AlemánDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

On The Garifuna People of Honduras

Încărcat de

Inti Martínez AlemánDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Inti Martnez Cultural Anthropology 11/21/2006

The Garfunas of Central America

Introduction The Garnagu, better known as Garfunas, live in the coast of Belize, Honduras, and Nicaragua. Their ethnicity is of African descent (West Africa, Bantu, Yoruba), combined with Carib or Calinago, thus creating the Black Caribs or Garfunas. In 1635, two Spanish ships carrying slaves to the West Indies were ship-wrecked near St. Vincent and the slaves on board escaped and took refuge among the Caribs (Cayetano, 1990). In 1797, after intermarrying with the Caribs and suffering many British attacks, about five thousand Black Caribs were rounded off by British soldiers and put on a boat destined to the islands of Roatn and Bonaca (now, Guanaja), Hondurashalf of Black Caribs dying during the trip. From here, they spread to mainland Honduras, north to Belize, and south to Nicaragua. Even though 80 percent of Garfunasfrom the 51 Garfuna villages in Central Americalive in Honduras (Yuscarn, 1990), most of the literature from and about Garfunas revolves around the Belizean population. Todays Garfunas are not the same Garfunas from two or three decades ago. Many Garfunas have left their native villages and now live in large cities like Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula, most of them well incorporated into the mestizo lifestyleyet still suffering from racial discrimination (Dzidzienyo & Oboler, 2005). There is also a very large Garfuna population in US cities like New York, New Orleans, Chicago, and Los Angeles (Yuscarn); these Garfunas send monthly remittances to their

family members in Honduras, which help their lives more affordable. Garfunas in Honduras are plagued by HIV/AIDS, propagated by mens sexually promiscuous habits and their endogamous marriage rules. Even though HIV/AIDS is widespread among the Garfunas, stigmatizing those infected is common (Stansbury, 2004). While the Garfuna language does not have distinct words for different marital unions, Garfunas distinguish three sorts of marital unions: legal, extralegal, and secondary. A legal marriage is one endorsed by a church (usually the Catholic Church). Extralegal unions are also common and entirely acceptable, although they lack the prestige of marriage (Kerns, 1983). Secondary unions are very rare and involve an additional, fully recognized, wife. However, the vast majority of village men claim to have only one spouse. A survey by Kerns shows that 77 percent of children live with at least one parent (60 percent with both parents). In Garfuna villages, men usually do the fishing and some horticulture, while women take care of the children at home; do the cleaning, cooking and washing; and walk every morning at five to take care of the garden (that might be miles away, in borrowed property). Men, for the most part, are irresponsible and sluggish, while women do most of the work for the family, resenting mens habits. The supernatural and religious rites are very private for the Garfunas. They rarely talk about what they do in their communities, and when asked about their religious beliefs and customs, they tend to respond in an evasive manner. Death is dealt with in a very peculiar manner: there are festivities combined with mourningrituals for the dead extend even after many years.

Birth, Death and the Afterlife Death and the dead constantly impinge on the world of the living. Certain signs presage an impending death: the appearance of a large black butterfly in the house, or the restlessness of infants during the night (Kerns). The Garfuna beliefs of the supernatural, the afterlife, and the current life blend into each other, making it very difficult to pinpoint where and why certain beliefs have originated. Feeding the dead, bathing the spirit of the dead, and praying to ancestors are common rituals among Garfunas. Talking about religious and burial rituals is very private for the Garfunas; they tend to no talk about what they do within their communities. Most mestizos take this secretiveness as a reflection of low self-esteem from part of the Garfunas or view their practices with much suspicion and disgust. Death is not the only event to which Garfunas dedicate rituals. Childbirth is an important and ritualized event. The birth of a child, per se, is only seen as a physical birthbut not as the birth of the child into society. For the Garfuna midwives, there are two events which symbolize the communitys welcoming of the new child. First, the spirits of the childs ancestors (called gubidas) are invoked for protection. Its inconceivable for the midwives to deliver a child without undergoing the child into this ritual. Midwives are very interested in finding out if the newborn has a special trait that might be beneficial for the community in the future. They carefully observe whether or not a newborn has a thin film around his or her head. This thin film is called lague and not all newborns have it; those who do have it end up becoming very good herb doctors, midwives, or spiritual leaderall highly respected positions among the Garfunas. Moreover, the placenta from the mothers womb is buried as a symbol of connection

between the newborn and the land (which is seen as a gift from God to all humanity). This burial is seen as a blessing upon the child. If the placenta is not buried and comes in contact with an animal, then the life of the newborn will be cursed (Idiquez, 1994). Second, the child is given a Catholic baptism, offering him or her to God with gratitude. Without the holy water or divinize from baptism, the childs vulnerability to illnesses, curses, and poor weather (as it affects growing crops, fishing, etc.) is high. The midwife usually opens the Bible to the Psalms (oftentimes Psalm 23) and places it on the bed or a nearby table. The holy water that falls on the baby is considered the most powerful tool to clean the soul for the afterlife and thus opens the door for salvation (Idiquez). This combination of ancestor invocation and Catholicism (called Afro-Catholic Syncretism by Idiquez) is well engrained in Garfuna culture. These rites are of crucial importance to the sociopolitical structure of Garfuna communities. Idiquez, quoting Hurbon, says that Garfunas believe God is the being without which all rituals and invocations to ancestral spirits would have no meaning or efficacy. Herb doctors, midwives, and spiritual leaders all fervently believe that they could not do a good job if it were not for the help of God. Their religious dedication is very strong; midwives, for example, when facing a difficult birth, use the thunder stone* or lidburi wayjulluru, and a cross in order to allow the ancestors work in favor of the birth. If the thunder stone is used without the cross, then the baby and/or the mother might be in danger of dying (Idiquez). The ancestral spirits are seen as the mediators between God and the world. Most ancestral spirits are good spirits, but there are bad spirits that represent the lives of dead

people who were rebellious with God and did not live moral lives. When someone dies, the ancestral spirits that were invoked when he or she was born take the body of the Garfuna and guide it towards its eternal home. These ancestral spirits or gubidas are invoked by a group of people of strong faith, while facing east, where the sun comes out, and where the gubidas reside. This group has to avoid crying, talking, or looking at the face of the deceased; doing this symbolizes offering the life of the Garfuna to God, with hopes that it will be received. Garfunas cannot conceive not praying for the soul of the deceased, because only animals die without being prayed for. The body and the soul are seen as inseparable for the Garfunas. Thus, the body has to be taken care of as well. After praying for the soul of the deceased, the spouse, close relatives, or elderly women of the community wash the body thoroughly in order to present it clean to God (Kerns). This rite is analogous to the baptism he or she received as a newborn. For Garfunas, dying is a memorable event that involves the whole community. Praying, washing, buying food and drinks, preparing meals, building a coffin, digging the grave, and carrying out mass for the deceased involves practically everyone in the community and can cost about the equivalent of $1300 (Kerns). Kerns says that wakes are sedate affairs early in the night. The men gamble or converse, a few women sing hymns, and others sit together talking quietly or help distribute food and rumEventually someone induces a few of the men to provide music for dancing, substituting wooden crates for drumsSome of the older women are sure to protest the impropriety of festive music and dance, but only halfheartedly and usually in vain. Soon enough they may take turn dancing themselves. Death ceremonies have a solemn purpose combined with a festive ambience. During the wake, women wail

without restraint. Wailing is a ritual skill that women cultivate.People criticize a woman who cries quietly or spiritlessly, calling her ungrateful. Anyone who comes in contact with the dead has to undergo a cleansing ritual. If he or she is not cleansed, he or she cannot go out to fish, hunt, or gather food without having bad luck and illness. This cleansing ritual involves burning together a termite nest, cow dung, and garlic. If one comes in contact with the dead one needs to immerse in this smoke during several minutes. Another type of cleansing involves bathing oneself with the lemon leaves tea (Idiquez). Moreover, the death ritual is not only for blessing the deceased, but also for blessing the community. By carrying out a death ritual properly, the community shows its obedience and love for God and the ancestorsthus receiving blessings from them. God is such a powerful and great being that the need of good ancestral spirits as intercessors is necessary. God is seen as a caring, loving, and protecting God. Jesus is also revered as the perfect example of lifestyle and servanthood. What Jesus did on this Earth is seen as the ultimate advocacy for justice. He is the archetype which the ancestral spirits follow. Jesus and the ancestors guide the dead towards eternity and are a source of inspiration and identity for the Garfuna people (Idiquez). After the burial, there are six other rites (most of them not obligatory) for the dead: the novena and ninth-night wake (arsaruni and belria); the end-of-mourning ceremony (tgurun ldu); bathing the spirit (amidahani); Requiem Mass and feasting (helmeserun hila and efduhani laugi lemsi); feeding the dead (chug); and feasting the dead (dg). A novena usually begins on the first or second Friday after burial. The prayers of the novena assure the repose of the soul andthe detachment of the deceased

from the world of the living. The ninth-night wake celebrates the same purpose of the novena, but is a merrier event involving cooking, drinking, conversing, and dancing. After the ninth-night is over, the altar dedicated for the defunct is torn down abruptly, causing some wailing from the relatives (Kerns). The end-of-mourning ceremony is held six months after burialThe day before the ceremony the mourning womenbake the bread that they will serve the following day with coffee and rum. During the 6 AM ceremony, older women pray with the close relative and then women ritually bathe in the beach. Each woman has a female partner, typically an aunt or an elder cousin, whom she has chosen to accompany her into the sea. Fully dressed and with their arms linked, each pair walks into the surf and out beyond the breakers. There the escorts of the mourning women submerge them, then help them up, repeating this twice again. After this, the women get dressed in the deceaseds house and start sipping rum and dancing punta until late morning or early afternoon, depending on how long the rum lasts or the dancers endure. Community members flock around the house and join the festivity (Kern). The bathing of the spirit takes place several months or years after a death. [A] close relative commonly has a dream in which the deceased man or woman requests a bath. Again, refreshments are prepared the day before bathing the spirit. The amidahani takes place in a yard, usually by the house where the deceased lived. The ceremony starts with invited guests and relatives before dawn, and does not take too long. The attendees gather around a shallow pit the size of a grave and the closest relative of the deceased throws a bucket of water into the pit. Then, in pairs, one person at the head with a bucket of cassava water and the other at the feet with a bucket of fresh water,

they dump water into the pit. [A] candle burns beside an offering of food and rum inside the house. For the Requiem Mass and feasting, the spirit of the dead requests these events to a close relative in form of a dream, about one or two years after his or her death. These events, according to Kern, are very similar to the novena and the ninth-night wake: prayers followed by feasting. The feeding and feasting of the dead, the last two death rituals, differ from the preceding rituals in a number of respects. Both of these originate after a chronic disease falls upon a close relative of the defunct. The shaman of the town and helpers summon the spirits to see why this person has fallen ill for so long. They usually find out that the spirit has not been appeased or granted a gift. Then, the shaman is told by the spirit more details about the ritual (either chug or dg, but not both): who is to contribute, the amount of the contribution, the various foods to be offered, the manner of the offerings disposal (either burial or disposal at sea), the length of the ceremony, and even the date. Oftentimes, the relatives negotiate with the spirits, in order to have more time to prepare. Chug and dg differ in cost, length, and attendance. Chug is a one-day affair, essentially an elaborate offering accompanied by frequent prayers to God, Christ, the Virgin Mary, and individual ancestors (Kern). Dg has long been the paramount ceremony for the dead, the most length, costly, and elaborate. In this three-day-and-night-long event, relatives from nearby townsand even those living abroadflock to the hometown of deceased and celebrate with drinking, dining, dancing, and conviviality. Lavish amounts of food and drinks are provided by the hosts. Anyone who dances in the dg, however, must bring a small

portion of rum as an offering. People come from far away to this celebration because it is known to cure illnesses that medical doctors have not been able to cure (Kern).

Conclusion The life of the Garfunas is full of mysticism and rituals that revolve around their conception of the supernatural. God and ancestral spirits are very important for the how the Garfuna people live their lives. The trinomial of God, the ancestors, and the land gives significance to the identity and unity of the Garfunas. Most of the religious practices are now longer common in Garfuna villages. What permeates the minds of Garfunas nowadays is thinking how to leave their village to study and get a job in a city, and buying the trendiest clothes and commodities. Young Garfunas see the practices, beliefs, and rituals of their parents and grandparents with skepticism and even mockery. The death rituals, specifically, are too cumbersome, costly, and lengthy to be put to practice nowadaysmany Garfunas work for someone else and cannot leave work without being fired or fined. Garfunas in cities no longer speak the Garfuna language, but still eat most of the food the Garfunas in villages eat. The richness of the Garfuna culture is vast, yet it has been decimated due to its contact with the modern world.

Reference List

Cayetano, S. (1989). Garfuna History, Language & Culture of Belize, Central America & the Caribbean. Belize: Unknown Publisher. Dzidzienyo, A., & Oboler, S. (2005). Neither Enemies nor Friends. New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan. England, S. (2006). Afro Central Americans in New York City: Garfuna Tales of Transnational Movements in Racialized Space. Gaineseville, FL: University Press of Florida. Idiquez, J. (1994). El Culto a los Ancestros: en la Cosmovisin Religiosna de los Garfunas de Nicaragua. Managua, Nicaragua: Instituto Histrico Centroamericano. Kerns, V. (1983). Women and the Ancestors. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press. Stansbury, J., & Sierra, M. (2004). Risks, stigma and Honduran Garifuna conceptions of HIV/AIDS. Social Science & Medicine, vol. 59, number 3, pp. 457-471. Retrieved November 25, 2006, from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. Yuscarn, G. (Lewis, William) (1990). Conociendo a la Gente Garfuna. Tegucigalpa, Honduras: Nuevo Sol Publicaciones.

The thunder stone is a very special stone which is used in all births as symbol of connection between the newborn, the Garfuna society, and the supernatural.

10

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Example of Text That Contains Present Perfect TenseDocument2 paginiThe Example of Text That Contains Present Perfect TenseRahmiSyariif100% (1)

- Financial Management - Risk and Return Assignment 2 - Abdullah Bin Amir - Section ADocument3 paginiFinancial Management - Risk and Return Assignment 2 - Abdullah Bin Amir - Section AAbdullah AmirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fairy Rebel PDFDocument2 paginiFairy Rebel PDFSamuel0% (1)

- Judgment - AmendedDocument6 paginiJudgment - AmendedInti Martínez AlemánÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fukuyama's "State Building"Document8 paginiOn Fukuyama's "State Building"Inti Martínez AlemánÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indictment - Superseding InformationDocument4 paginiIndictment - Superseding InformationInti Martínez AlemánÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Ned Nodding's "Caring"Document12 paginiOn Ned Nodding's "Caring"Inti Martínez Alemán100% (1)

- Estatutos Vigentes de UNITECDocument14 paginiEstatutos Vigentes de UNITECInti Martínez AlemánÎncă nu există evaluări

- Labor Law Review Questions and AnswersDocument151 paginiLabor Law Review Questions and AnswersCarty MarianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Veep 4x10 - Election Night PDFDocument54 paginiVeep 4x10 - Election Night PDFagxz0% (1)

- Internship ProposalDocument6 paginiInternship ProposalatisaniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cranial Deformity in The Pueblo AreaDocument3 paginiCranial Deformity in The Pueblo AreaSlavica JovanovicÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4th Quarter Grade 9 ExamDocument4 pagini4th Quarter Grade 9 ExamAnnie Estaris BoloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Section D Textual QuestionsDocument52 paginiSection D Textual Questionsxander ganderÎncă nu există evaluări

- NyirabahireS Chapter5 PDFDocument7 paginiNyirabahireS Chapter5 PDFAndrew AsimÎncă nu există evaluări

- John 20 Study GuideDocument11 paginiJohn 20 Study GuideCongregation Shema YisraelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teacher LOA & TermsDocument3 paginiTeacher LOA & TermsMike SchmoronoffÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project BBADocument77 paginiProject BBAShivamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adv Tariq Writ of Land Survey Tribunal (Alomgir ALo) Final 05.06.2023Document18 paginiAdv Tariq Writ of Land Survey Tribunal (Alomgir ALo) Final 05.06.2023senorislamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Task 12 - Pages 131-132 and Task 13 - Pages 147-148 (Bsma 2c - Zion R. Desamero)Document2 paginiTask 12 - Pages 131-132 and Task 13 - Pages 147-148 (Bsma 2c - Zion R. Desamero)Zion EliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Current Technique in The Audiologic Evaluation of Infants: Todd B. Sauter, M.A., CCC-ADocument35 paginiCurrent Technique in The Audiologic Evaluation of Infants: Todd B. Sauter, M.A., CCC-AGoesti YudistiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lab Exercise: 8Document5 paginiLab Exercise: 8Test UserÎncă nu există evaluări

- ADDIE - Model - For - E-Learning - Sinteza2017 - Corr-With-Cover-Page-V2 (New)Document6 paginiADDIE - Model - For - E-Learning - Sinteza2017 - Corr-With-Cover-Page-V2 (New)arief m.fÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dnyanadeep's IAS: UPSC Essay Series - 7Document2 paginiDnyanadeep's IAS: UPSC Essay Series - 7Rahul SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- DaybreaksDocument14 paginiDaybreaksKYLE FRANCIS EVAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bar Graphs and HistogramsDocument9 paginiBar Graphs and HistogramsLeon FouroneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heat Transfer OperationsDocument10 paginiHeat Transfer OperationsShafique AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Michelle Kommer Resignation LetterDocument1 paginăMichelle Kommer Resignation LetterJeremy TurleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- RUBEEEEDocument44 paginiRUBEEEEAhlyssa de JorgeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evolution of Corporate Social Responsibility in IndiaDocument12 paginiEvolution of Corporate Social Responsibility in IndiaVinay VinuÎncă nu există evaluări

- N Advocates Act 1961 Ankita218074 Nujsedu 20221008 230429 1 107Document107 paginiN Advocates Act 1961 Ankita218074 Nujsedu 20221008 230429 1 107ANKITA BISWASÎncă nu există evaluări

- IndexDocument3 paginiIndexBrunaJ.MellerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quiz Simple Present Simple For Elementary To Pre-IntermediateDocument2 paginiQuiz Simple Present Simple For Elementary To Pre-IntermediateLoreinÎncă nu există evaluări

- 17373.selected Works in Bioinformatics by Xuhua Xia PDFDocument190 pagini17373.selected Works in Bioinformatics by Xuhua Xia PDFJesus M. RuizÎncă nu există evaluări

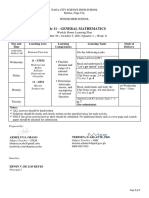

- General Mathematics - Module #3Document7 paginiGeneral Mathematics - Module #3Archie Artemis NoblezaÎncă nu există evaluări