Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

PULITZER, 'Rachel Harrison' FA 2010

Încărcat de

sam_pulitzer4195Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

PULITZER, 'Rachel Harrison' FA 2010

Încărcat de

sam_pulitzer4195Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

On my way to Rachel Harrison's Brooklyn studio, I had one thing that I was going to bug her about: clowns.

Two groups of clowns in particular: the hedonistic clowns of '70s hard-rock, KISS, and the Gacy-inspired abject n-metallers, Slipknot. Having both made appearances in Harrison's work as often as some 20th-century artists like Andy Warhol and Frank Stellaartists who appear in name only or in Lawler-esque photographic fragmentsI figured it might be a way to explore the cultural references that circulate on the other side of the gallery's walls. One of Harrison's most important contributions to the cultural dialogue surrounding contemporary art in the roughly 20 years that she has exhibited is her non-hierachical use of cultural idioms. These idioms, one side of the coin, inform art's existence as a gallery-based, museological experience but, on the other cheaperside of the same coin, idioms that inform the aesthetic experiences attached to America's far more psychologically dominant commercial culture. Yet as these aesthetic opposites are presented with neither one above the other, Harrison lays bare the inapparent correspondence that communes between these estranged cultural forms one is just as likely to find a clown in a museum as you might a masterpiece in a carnival, so to speak. After talking with Harrison at length about America's clown industryboth KISS and Slipknot have mobilized armies of consumers to purchase their floods of merchandise, it becomes clear that many of the initial influences lumped onto her work, who unfailingly range from Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol to Franz West and Martin Kippenberger, don't quite provide a complete map for navigating the complex emotional responses embedded throughout Harrison's materially and semiotically intricate referential networks. Which is not to say there is no rapport between Harrison and these canonical artists, as there remains a considerable one. Limiting Harrison's practice to an exclusively museological interpretation often obscures the cross-cultural and anthropological examinations core to Harrison's novel approach. While her work's irreverent appearance easily fits into the global(-ized) dialogue governing sculpture's current "unmonumentality," that her work also acts as a communicative relay to the cringe-worthy mass aesthetics whose refined exclusion stipulates contemporary art is not to be ignored. This is, no doubt, the reason why when I queried Harrison for her primary influences, none of the previously mentioned artists immediately entered the discussion. Rather it was an unexpected collection of conceptual, performance and video artists: Adrian Piper, Yvonne Rainer, Chris Burden, Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, to name a few. And after talking clowns for an hour, it was only a matter of time before Bruce Nauman's video installation Clown Torture (1987) entered the discussion. With its documentation of 6 "entertainers" enduring not only a torturous gauntlet of repeated tasks outlined by Nauman but also the scrutiny of the viewer's mediated gaze, one must wonder if they have found an art historical shortcut to accessing the complicated network of references, puns and associations of Harrison's artistic aggregates. The parallels between Nauman's violently interrogated clowns and the oft-idealized museological art object scrutinized by Harrison are undeniable: they are both are here for our enjoyment, whether they like it or not. Another entertainer scrutinized by their viewing public surprisingly mentioned by Harrison during our conversation was Karen Carpenter. More specifically, the Barbie doll who "played" Karen Carpenter in Todd Haynes' controversial first film, Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1987)a film that garnered both acclaim and infamy for depicting the tragic life of this squeaky-clean pop singer entirely with the popular plastic figurines in place of human actors. When discussing her favorite aspects of Superstar, Harrison emphasized that in order to give the doll a greater likeness to the anorexic star,

Haynes reportedly had to sand down the Barbie's arms and legslimbs whose skinniness most people presume to be readymade. Even when watching the film, the visual gag of substituting a doll for a human actor, especially in a highly dramatic context fraught with tragedy, first elicits giggles given such a conceit's ironic wit. However, the "dollness" of Haynes' actors quickly fades as the pop narrative's tragedy mounts so that, by the film's finale, Karen's tragedy is doubly amplified by the haunting absence of a living performer. That a slight maimed consumer good is as adept at triggering an audience's sympathy certainly reveals much about the profound psychological interaction at work between objects that scream "kitsch" and the subjects who consume them. I, for one, never thought of Haynes' film when considering Harrison's Barbie-centric work, Untitled (Becky Friend of Barbie) (2001). Well, not a Barbie, rather Barbie's handicapped "friend," "Becky." Untitled (Becky Friend of Barbie), a component of Harrison's immersive installation Perth Amboy (2001), rests within a labyrinth of upright cardboard sheets and a photographic series of a suburban New Jersey window where the Virgin Mary was believed to have been sighted. Included among three other worksall riffing on the consecrated museological use of pedestalsBecky is one of four different figurines who contemplate a different aesthetic object: a Confucian monk scrutinizes a "Scholar's Rock" (in this case, one of Harrison's signature sculptural masses humorously painted the same color as the scholar's robe); a family of dalmatians consider a mangled business envelope as a towering abstract sculpture; an Indian chief studies a humorously small easel painting, is he pondering the easel's status within our post-Greenbergian contemporary context? As for the wheelchair-bound Becky, she is grinning into a photograph that Harrison had taken of a film studio's vastly unpopulated green screen. With Superstar's canny object-subject substitutions now in mind, Harrison's Untitled (Becky Friend of Barbie) appears as an update of Caspar David Friedrich's romantic masterpiece, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818), for a world whose claims of handicap-accessibility and political correctness seem increasingly titular, a fantasy projected on to the worlds' manifold surfaces. However, where Friedrich's famous painting depicted a scenario suffused with the romantic ideal of sublimity, that ambiguous sensation of terror cloaked in exhilaration, Harrison's 21st-century remake/remodel swaps out the sublime for the sublimated, where trauma cloaks contentment, comedy masks tragedy. Or in Becky's specific case, the de-sublimated, as this smiling doll appears in gleeful thrall to the digital age's most prominent aesthetic void, this abstract media surface stripped bare of its projected fantasies. Harrison's non-hierachicial use of kitsch within the highly governed contexts of contemporary art finds one of its unlikeliest creative precedents in one of her former Wesleyan college professors: the renowned experimental composer and musician Alvin Lucier. Taking John Cage's non-traditional use of everyday objects as his starting point, Lucier has employed non-musicaland potentially kitschyobjects to realize a number of his innovative compositions. Sometimes alone and in other instances accompanying traditional instrumentation, Lucier's repertoire of non-musical instrumentation has included ping pong balls, carbon dioxide-filled balloons, an electronic bird, a cooking pan or a teapot, to name a fewobjects that certainly wouldn't be out of place nestled in one of Harrison's sculptural aggregates. Perhaps Lucier's most notable contribution to the historical dialogue initiated by Cage's use of silence as a compositional tool is the way Lucier transforms these customary objects into devices that sonically articulate the very silence that surrounds thema phenomenon experienced in the pioneering Bird and Person Dyning (1975), for example. Lucier literally amplifies the inapparent sensory bondsvia normally inaudible resonant frequenciesthat are always present, yet rarely

experienced, between the object's performative silence and the corresponding world in which it exists. Yet the sound of this sensory correspondence is not one of lyrical sonority, of an etherial harmony akin to the supposed music of celestial spheres. Rather Lucier's spatially-articulating sonic interrelations are a highly choreographed version of the musical scenario familiar to anyone who has ever been to a rock concert: a musician either accidentally or intentionallyturns their instrument (the input signal) toward their amplifier (the output) and unleashes a banshee-like wail of ear-splitting noise, a shrill dissonance better known as feedback. And thanks to the fetished imagery associated with commercial music, the formal omission of this silence's ever-present space from commercial music's aural reality takes on a highly allegorical tone, pointing very much so to the highly repressed bond between one cultural signal and another. One of Harrison's new sculptures, Siren Serenade (2010), deals with both music and the signals through which it finds its aesthetic formyet in an aesthetic space most often construed as "sculpture." Named for the Gene Krupa record nestled in its side, Harrison's eerily black new work most noticeably includes a They Live-esque satellite dish cropping out from its top. What are the transmissions the work receives? Is it the very siren's serenade stuck into the other side of the work? Or is it perhaps a signal beyond the work's immediate sculptural space, where the sculpture isn't an autonomous creation but rather a by-product of this mediated correspondence; that the sculpture didn't sprout the readymade objects adorning it but rather the readymade objects sprouted the sculpture between them. There is a great similarity between the mythological serenade invoked by the work's titlethat is the seductive song of the sirens repressed by Odysseus and his crew so as not to veer fatally off courseto the same inapparent aural space that can warp a pop song into something physically unsettling; the repressed aural space that, when amplified, can veer a commercial ditty off its course, crashing it into the listener's ears. Much can also be said of Harrison's dissonant interrelation of readymade kitsch with the readymade forms of museological art. It is as if Harrison's input signal of silent curios swoops in front of the white-walled gallery output signal, loudly magnifying the inapparent correspondence between these two seemingly irreconcilable cultural forms. Given the formal similarity between Lucier's and Cage's musical silence and the visual silence of the green cinematic surface-turned-void that en-trances Becky, Harrison's soundless readymades and found objects are certainly deceiving appearance wise. As, within Harrison's critical oeuvre, the museological distinctions like "sculpture," "readymade" and "kitsch" that are piled onto the interpretive surfaces of Harrison's sculptural and non-sculptural objects are exposed as noisy special effects fundamental to the market appeal of the big-budget blockbuster better known as contemporary art. Sam Pulitzer is a writer and an artist living in New York. Rachel Harrison was born in 1966 in New York where she lives and works. Selected solo shows: 2010: Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Whitechapel Gallery, London. 2009: Center for Curatorial Studies, Hessel Museum, Bard College; Portikus, Frankfurt (DE). 2008: Meyer Kainer, Vienna; Le Consortium, Dijon. 2007: Migros Museum, Zurich; Greene Naftali, New York. 2006: Christian Nagel, Cologne (with Michael Krebber); The Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver (with Scot Lyall); LACE, Los Angeles. 2005: Transmission Gallery, Glasgow. 2004: SFMOMA, San Francisco; Camden Art Centre, London; Arndt & Partner, Berlin; Greene Naftali, New York. 2003:

Bergen Kunsthall (NO). 2002: Milwaukee Art Museum (US); Arndt & Partner, Berlin. 2001: Greene Naftali, New York. 1999: Greene Naftali Gallery, New York. 1997: Greene Naftali Gallery, New York. 1996: Arena Gallery, Brooklyn. Selected group shows: 2010: The Original Copy: Photography of Sculpture, 1839 to Today, MoMA, New York. 2009: Venice Biennale; Tate Triennial. 2008: Front Room: Dieter Roth and Rachel Harrison, Baltimore Museum of Art; Whitney Biennial, New York. 2007: Paul Thek in the Context of Todays Contemporary Art, ZKM, Karlsruhe; Unmonumental, New Museum, New York; The Hamsterwheel, Arsenale di Venezia, Venice / Festival de Printemps de Septembre, Toulouse (FR); CASM, Barcelona / Malm Konsthall, Sweden. 2006: The Uncertainty of Objects and Ideas: Recent Sculpture, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC; Berlin Biennale. 2005: Carnegie International, Pittsburgh; When Humor Becomes Painful, Migros Museum, Zurich. 2004: Speaking with Hands: Photographs from The Buhl Collection, Guggenheim Museum, New York. 2003: Venice Biennale. 2002: Whitney Biennial, New York; Stories, Haus der Kunst, Munich. 2001: Off the Wall, Gallery 400 University of Illinois, Chicago. 2000: Walker Evans & Company, MoMA, New York / J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Greater New York, P.S.1, New York. 1999: DOPE. An XXX-Mas Show, American Fine Arts, Co., New York; Still Life, State University of New York College at Old Westbury. 1998: New Photography 14, curated by Darsie Alexander, MoMA, New York. 1997: Current Undercurrent: Working in Brooklyn, Brooklyn Museum of Art. 1995: Looky Loo, Sculpture Center, New York.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Beatitude in Robert Ashley's Perfect LivesDocument36 paginiBeatitude in Robert Ashley's Perfect Livesjamil pimentelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions, Volume Two: A Biography of the Works through MavraDe la EverandStravinsky and the Russian Traditions, Volume Two: A Biography of the Works through MavraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Benjamin's Aura, Levine's Homage and Richter's EffectDocument26 paginiBenjamin's Aura, Levine's Homage and Richter's Effectaptureinc100% (1)

- The Rite of Spring S Reception and Influ PDFDocument14 paginiThe Rite of Spring S Reception and Influ PDFTodor ToshkovÎncă nu există evaluări

- A New Show Restages Matthew Barney's 1991 Breakthrough, and It's Even Better The Second TimeDocument11 paginiA New Show Restages Matthew Barney's 1991 Breakthrough, and It's Even Better The Second TimeSandro NovaesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jon Hassell - 1977 - Vernal EquinoxDocument7 paginiJon Hassell - 1977 - Vernal EquinoxNicoloboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Robert RauschenbergDocument6 paginiRobert RauschenbergeasyreaderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Occasional Nuggets Spring 2015Document16 paginiOccasional Nuggets Spring 2015Micah SalkindÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rp183 Obituary Cunningham LoureedDocument4 paginiRp183 Obituary Cunningham LoureedOlivia Neves MarraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foul Perfection - Kelley On PaulDocument6 paginiFoul Perfection - Kelley On PaulAlexnatalieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Craig Owens - Is There Life After The Death of The AuthorDocument10 paginiCraig Owens - Is There Life After The Death of The AuthorEsperanza ColladoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cronin ReillyDocument2 paginiCronin Reillymaura_reilly_2Încă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of Rite of SpringDocument51 paginiAnalysis of Rite of SpringMassimiliano BaggioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Movie Music InterviewDocument6 paginiMovie Music InterviewAntoine LagneauÎncă nu există evaluări

- Musicophobia or Sound Art and The Demands of Art TheoryDocument12 paginiMusicophobia or Sound Art and The Demands of Art TheoryAlex TentorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Disciplined Excess: The Minimalist / Maximalist Interface in Frank Zappa and Captain BeefheartDocument13 paginiDisciplined Excess: The Minimalist / Maximalist Interface in Frank Zappa and Captain BeefheartPaul RizzutoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diamond, Musically Imagined CommunitiesDocument5 paginiDiamond, Musically Imagined CommunitiesMark TrentonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art MovementsDocument51 paginiArt MovementsIsaac Johnson AppiahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of Rite of SpringDocument51 paginiAnalysis of Rite of SpringTom Borg100% (3)

- Taruskin - The History of What - 2010Document11 paginiTaruskin - The History of What - 2010JUAN CARLOS CORONEL TENORÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Theme Popular vs. Elite in The Hollywood Musical: SyntaxDocument9 paginiThe Theme Popular vs. Elite in The Hollywood Musical: SyntaxAdriana AlarcónÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rioting With Stravinsky. A Particular Analysis of "The Rite of The Spring"Document51 paginiRioting With Stravinsky. A Particular Analysis of "The Rite of The Spring"tycheth100% (1)

- nf39 12reviews 0Document17 pagininf39 12reviews 0CesarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Musicophobia, or Sound Art and The Demands of Art TheoryDocument20 paginiMusicophobia, or Sound Art and The Demands of Art TheoryricardariasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Running Head: ART HISTORYDocument4 paginiRunning Head: ART HISTORYPiya ChowdhuryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Synesthesia: Surrealism in The Beatles' MusicDocument5 paginiSynesthesia: Surrealism in The Beatles' MusicMarco MauriziÎncă nu există evaluări

- "My Music Is Words" - The Poetics of Sun RaDocument50 pagini"My Music Is Words" - The Poetics of Sun Raapi-26023436100% (1)

- The Cosmic American: Harry Smith's Alchemical ArtDocument11 paginiThe Cosmic American: Harry Smith's Alchemical ArtWilliam RauscherÎncă nu există evaluări

- Say That A Single Tone Played On The Organ or Harpsichord Sounds PassionateDocument9 paginiSay That A Single Tone Played On The Organ or Harpsichord Sounds PassionateVaizal AndriansÎncă nu există evaluări

- Essay StravinskyDocument6 paginiEssay StravinskyRael RentÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scriabin's Symbolist Plot Archetype in The Late Piano SonatasDocument29 paginiScriabin's Symbolist Plot Archetype in The Late Piano SonatasVintÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Priest of BeautyDocument16 paginiThe Priest of Beautyrhuticarr100% (1)

- West Virginia University Press: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPDocument4 paginiWest Virginia University Press: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPNasrullah MambrolÎncă nu există evaluări

- J.S. Bach The Rebel - Lapham's QuarterlyDocument4 paginiJ.S. Bach The Rebel - Lapham's Quarterlyalfredo_ferrari_5Încă nu există evaluări

- Rae - 2, Symbolism and AllegoryDocument71 paginiRae - 2, Symbolism and AllegoryjaiversonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hans Keller: HubermanDocument15 paginiHans Keller: HubermanAndrew WilderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Monkey Beach "Close, Close"Document17 paginiMonkey Beach "Close, Close"peter_yoon_14Încă nu există evaluări

- Raqib Shaw at The Pace Gallery - Review (Published in Art & Deal Magazine, January 2014)Document6 paginiRaqib Shaw at The Pace Gallery - Review (Published in Art & Deal Magazine, January 2014)Renuka SawhneyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Listen To This, by Alex RossDocument9 paginiListen To This, by Alex RossBenjamin WheelerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Under The Influence CHRISTOPHER S. WOODDocument9 paginiUnder The Influence CHRISTOPHER S. WOODMax ElskampÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adorno Alienated Masterpiece Beethoven PDFDocument15 paginiAdorno Alienated Masterpiece Beethoven PDFPhasma3027100% (1)

- Alex Ross: The Rest Is Noise, Review: Douglas C. WadleDocument17 paginiAlex Ross: The Rest Is Noise, Review: Douglas C. WadleWinner SilvestreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Works of Eva HesseDocument4 paginiWorks of Eva HesseMarte Prado del CabrónÎncă nu există evaluări

- Visions and Sounds of Popular Culture in PDFDocument9 paginiVisions and Sounds of Popular Culture in PDFAntonisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Steve Reich (Taruskin)Document6 paginiSteve Reich (Taruskin)letrouvereÎncă nu există evaluări

- Et in Arcadia EgoDocument5 paginiEt in Arcadia Ego69telmah69Încă nu există evaluări

- Ijcs 29549 StromDocument9 paginiIjcs 29549 StromRomario SouzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Traces: Whatdoyoumeanandhowdoyoumeanit: FRANK O'HARA. The and Pop ArtDocument5 paginiTraces: Whatdoyoumeanandhowdoyoumeanit: FRANK O'HARA. The and Pop ArtThisisLuizÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Mechanics of Transcendence On The SoDocument15 paginiThe Mechanics of Transcendence On The SoOrnebÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fairy Tale Opera and The Crossed Desires of Words and MusicDocument13 paginiFairy Tale Opera and The Crossed Desires of Words and MusicGorkem AytimurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Songs, Anti-Symphonies and Sodomist MusicDocument33 paginiSongs, Anti-Symphonies and Sodomist MusicM SerdaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adorno Alienated MasterpieceDocument15 paginiAdorno Alienated MasterpieceAnonymous zzPvaL89fGÎncă nu există evaluări

- In The Blind Field: Hopper and The Uncanny: Margaret IversenDocument21 paginiIn The Blind Field: Hopper and The Uncanny: Margaret IversenJane LÉtrangerÎncă nu există evaluări

- White On WhiteDocument32 paginiWhite On WhiteFelipeCussenÎncă nu există evaluări

- We Bring Our Lares With Us Bodies and Domiciles in The Sculpture of Louise BourgeoisDocument17 paginiWe Bring Our Lares With Us Bodies and Domiciles in The Sculpture of Louise Bourgeoisapi-317637060Încă nu există evaluări

- The Painted BirdDocument8 paginiThe Painted BirdKai WikeleyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Frank O'Hara's Process PoemsDocument11 paginiFrank O'Hara's Process PoemsRita AgostiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sun Went inDocument32 paginiThe Sun Went indezbatÎncă nu există evaluări

- HakdogDocument3 paginiHakdogCarmina Dineros100% (1)

- 2018-12-14 - DD Presentation - GENSLER Responses - San Salvador - HCDocument81 pagini2018-12-14 - DD Presentation - GENSLER Responses - San Salvador - HCarturo montañaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Influence of Inter-Anneal and Cold Rolling Processes On Key Lithographic Sheet PropertiesDocument218 paginiThe Influence of Inter-Anneal and Cold Rolling Processes On Key Lithographic Sheet PropertiesHaryadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 2 Building DrawingsDocument24 paginiChapter 2 Building Drawingsnaimamkusa1974Încă nu există evaluări

- 2008 Craigslist Foundation NY Tri-State Nonprofit Boot Camp Program (Small)Document88 pagini2008 Craigslist Foundation NY Tri-State Nonprofit Boot Camp Program (Small)Craigslist Foundation100% (5)

- 6770Document138 pagini6770Edward Xuletax Torres BÎncă nu există evaluări

- 4060Document58 pagini4060Davis TorresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Banana Boy Amigurumi - Tales of Twisted Fibers PDFDocument5 paginiBanana Boy Amigurumi - Tales of Twisted Fibers PDFmafaldas100% (1)

- Diksiyonaryong Biswal NG Arkitekturang Filipino PDFDocument123 paginiDiksiyonaryong Biswal NG Arkitekturang Filipino PDFKaila Weygan93% (15)

- Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Air Itam Ujian Prestasi 1 EnglishDocument5 paginiSekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Air Itam Ujian Prestasi 1 Englishsadrian2010Încă nu există evaluări

- Manga Translation and IntercultureDocument17 paginiManga Translation and IntercultureJônathas AraujoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Evolution of The Language of CinemaDocument14 paginiThe Evolution of The Language of CinemaIhjas AslamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Techniques For Voice ControlDocument3 paginiTechniques For Voice ControlLorena Do ValÎncă nu există evaluări

- Figure Drawing - Foreshortening - The Figure in PerspectiveDocument16 paginiFigure Drawing - Foreshortening - The Figure in Perspectivejationona0% (1)

- Peristil 62 Dpuh 009 019Document11 paginiPeristil 62 Dpuh 009 019elvis shalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Southern GP7 HarpeDocument63 paginiSouthern GP7 Harpepwmvsi100% (1)

- Module 1 Mimaropa Arts and CraftsDocument17 paginiModule 1 Mimaropa Arts and Craftsava munozÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tone Colour PDFDocument23 paginiTone Colour PDFAndres gÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Burlington Magazine Publications, LTDDocument5 paginiThe Burlington Magazine Publications, LTDByzantine PhilologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Camp 2012 ETA ReportDocument26 paginiEnglish Camp 2012 ETA Reportsal811110Încă nu există evaluări

- VSKunstefees Persverklaring:Media Release 3 Mei:May 2017Document5 paginiVSKunstefees Persverklaring:Media Release 3 Mei:May 2017Ricardo PeachÎncă nu există evaluări

- Daniel LibeskindDocument8 paginiDaniel LibeskindAshdeep SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Lighting HandbookDocument2 paginiThe Lighting HandbookDardakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guia Ing Sagrado Corazon RexpapersDocument11 paginiGuia Ing Sagrado Corazon RexpapersAlex Manchabajoy100% (1)

- Mail and The Knight in Renaissance Italy PDFDocument78 paginiMail and The Knight in Renaissance Italy PDFHugh KnightÎncă nu există evaluări

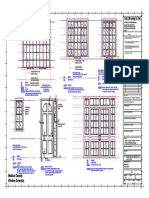

- Window and Door ScheduleDocument1 paginăWindow and Door ScheduleCharles WainainaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lev Manovich On Totalitarian Inter ActivityDocument3 paginiLev Manovich On Totalitarian Inter ActivityHerminio BussacoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fancy YarnsDocument7 paginiFancy Yarnsiriarn100% (1)

- PZO9504 U1 - Gallery of Evil PDFDocument36 paginiPZO9504 U1 - Gallery of Evil PDFJhaxius100% (9)

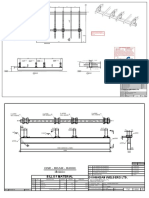

- Mono RailDocument6 paginiMono RailExcelÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityDe la EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (24)

- Do Dead People Watch You Shower?: And Other Questions You've Been All but Dying to Ask a MediumDe la EverandDo Dead People Watch You Shower?: And Other Questions You've Been All but Dying to Ask a MediumEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (20)

- Dogland: Passion, Glory, and Lots of Slobber at the Westminster Dog ShowDe la EverandDogland: Passion, Glory, and Lots of Slobber at the Westminster Dog ShowÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything about Race, Gender, and Identity―and Why This Harms EverybodyDe la EverandCynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything about Race, Gender, and Identity―and Why This Harms EverybodyEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (221)

- Welcome to the United States of Anxiety: Observations from a Reforming NeuroticDe la EverandWelcome to the United States of Anxiety: Observations from a Reforming NeuroticEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (10)

- The Season: Inside Palm Beach and America's Richest SocietyDe la EverandThe Season: Inside Palm Beach and America's Richest SocietyEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (5)

- Lost in a Good Game: Why we play video games and what they can do for usDe la EverandLost in a Good Game: Why we play video games and what they can do for usEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (31)

- The Canceling of the American Mind: Cancel Culture Undermines Trust, Destroys Institutions, and Threatens Us All—But There Is a SolutionDe la EverandThe Canceling of the American Mind: Cancel Culture Undermines Trust, Destroys Institutions, and Threatens Us All—But There Is a SolutionEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (16)

- You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the BreakupDe la EverandYou Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the BreakupÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women's AngerDe la EverandRage Becomes Her: The Power of Women's AngerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (184)

- 1963: The Year of the Revolution: How Youth Changed the World with Music, Fashion, and ArtDe la Everand1963: The Year of the Revolution: How Youth Changed the World with Music, Fashion, and ArtEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5)

- Alright, Alright, Alright: The Oral History of Richard Linklater's Dazed and ConfusedDe la EverandAlright, Alright, Alright: The Oral History of Richard Linklater's Dazed and ConfusedEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (23)

- As You Wish: Inconceivable Tales from the Making of The Princess BrideDe la EverandAs You Wish: Inconceivable Tales from the Making of The Princess BrideEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (1182)

- Greek Mythology: The Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes Handbook: From Aphrodite to Zeus, a Profile of Who's Who in Greek MythologyDe la EverandGreek Mythology: The Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes Handbook: From Aphrodite to Zeus, a Profile of Who's Who in Greek MythologyEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (72)

- Silver Screen Fiend: Learning About Life from an Addiction to FilmDe la EverandSilver Screen Fiend: Learning About Life from an Addiction to FilmEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (182)

- Attack from Within: How Disinformation Is Sabotaging AmericaDe la EverandAttack from Within: How Disinformation Is Sabotaging AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5)

- Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black & White, Body and Soul in American MusicDe la EverandGood Booty: Love and Sex, Black & White, Body and Soul in American MusicEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (7)

- Made-Up: A True Story of Beauty Culture under Late CapitalismDe la EverandMade-Up: A True Story of Beauty Culture under Late CapitalismEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (3)

- In the Form of a Question: The Joys and Rewards of a Curious LifeDe la EverandIn the Form of a Question: The Joys and Rewards of a Curious LifeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (8)

- Last Night at the Viper Room: River Phoenix and the Hollywood He Left BehindDe la EverandLast Night at the Viper Room: River Phoenix and the Hollywood He Left BehindEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (48)

- Don't Panic: Douglas Adams and the Hitchhiker's Guide to the GalaxyDe la EverandDon't Panic: Douglas Adams and the Hitchhiker's Guide to the GalaxyEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (488)

- How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America: EssaysDe la EverandHow to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America: EssaysEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (12)

- Sex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveDe la EverandSex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (22)