Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Sandiganbayan Jurisdiction Over Criminal Cases Against Municipal Mayors Upheld

Încărcat de

Martin MartelDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Sandiganbayan Jurisdiction Over Criminal Cases Against Municipal Mayors Upheld

Încărcat de

Martin MartelDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

G.R. Nos.

122297-98

January 19, 2000

CRESCENTE Y. LLORENTE, JR., petitioner, vs. SANDIGANBAYAN and PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, respondents. PARDO, J.: The case before the Court is a special civil action for certiorari1 assailing the jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan over the criminal cases against then municipal mayor Crescente Y. Llorente, Jr. for violations of Republic Act No. 3019, as amended. Petitioner Crescente Y. Llorente, Jr. was elected municipal mayor of Sindangan, Zamboanga in 1988 and 1992. On May 8, 1995, he was a candidate for congressman, second district of Zamboanga del Norte, and was duly elected. On August 6, 1993, the Office of the Special Prosecutor2 filed with the Sandiganbayan an information3 against Crescente Y. Llorente, Jr., municipal mayor of Sindangan, Zamboanga del Norte, P/Sgt. Juanito Caboverde and Jose Dy for violation of Section 3 (e), Republic Act No. 3019, as amended, committed as follows: That on or about June 12, 1989, in the Municipality of Sindangan, Zamboanga del Norte, and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, accused Crescente Y. Llorente, Jr., Municipal Mayor of Sindangan, Zamboanga del Norte and P/Sgt. Juanito Cadoverde of the defunct Integrated National Police and as such public officers and the other accused Jose Dy, a private individual, conspiring with each other and acting with evident bad faith, did then and there, willfully, unlawfully and criminally seized (sic) 930 sawn knockdown wooden boxes owned by Godofredo M. Diamante without any search and seizure warrant and without issuing any receipt of seizure thereby causing undue damage and injury to said Godofredo M. Diamante and this offense was committed in relation to the office of the said public officers. CONTRARY TO LAW. Manila, August 6, 1993. (s/t) GUALBERTO J. DE LA LLANA Special Prosecution Officer III4 On February 2, 1994, the three accused were arraigned before the Sandiganbayan and pleaded not guilty. On March 31, 1995, the Office of the Ombudsman5 filed with the Sandiganbayan another information6 against petitioner for violation of Section 3 (f), Republic Act No. 3019, as amended, committed as follows: That on or about July 5, 1993, and for sometime subsequent thereto, in Sindangan, Zamboanga del Norte, Philippines, and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the above-named accused, a public officer, being then the Municipal Mayor of Sindangan, Zamboanga del Norte, with grave abuse of authority, did then and there wilfully, unlawfully and criminally refuse to issue Mayor's permit to the ice plant and resawmill/box factory of R. F. Diamante and family, without sufficient justification, after due demand and payment of license fees were made, said refusal to grant Mayor's permit being not only personal but for the purpose of giving undue advantage to similar businesses in town and as an act of discriminating against the interest of the complainant to the latter's damage and prejudice.1wphi1.nt CONTRARY TO LAW. Manila, Philippines, March 31, 1995 (s/t) DANIEL B. JOVACON, JR. Special Prosecution Officer I7 The trial of both criminal cases before the Sandiganbayan has not begun.

On May 16, 1995, Congress enacted Republic Act No. 7975, 8 amending Section 4 of Presidential Decree No. 1606,9 providing: Sec. 4. Jurisdiction The Sandiganbayan shall exercise original jurisdiction in cases involving: a. Violations of Republic Act No. 3019, as amended, otherwise known as the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, Republic Act 1379, and Chapter II, Section 2, Title VII of the Revised Penal Code, where one or more of the principal accused are officials occupying the following positions in the government, whether in a permanent, acting or interim capacity, at the time of the commission of the offense: (1) Officials of the executive branch occupying the positions of regional director or higher, otherwise classified as Grade "27" and higher, of the Compensation and Position Classification Act of 1989 (Republic Act No. 6758), specifically including: (a) Provincial governors, vice governors, members of the sangguniang panlalawigan, and provincial treasurers, assessors, engineers, and other provincial department heads; (b) City mayors, vice mayors, members of the sangguniang panglungsod, city treasurers, assessors, engineers, and other city department heads; (c) Officials of the diplomatic service occupying the position of consul and higher; (d) Philippine army and air force colonels, naval captains, and all other officials of higher rank; (e) PNP chief superintendent and PNP officers of higher rank; (f) City and provincial prosecutors and their assistants, and officials and prosecutors in the Office of the Ombudsman and special prosecutor; (g) Presidents, directors, or trustees, or managers of government-owned or controlled corporations, state universities or educational institutions of foundations. (2) Members of Congress and officials thereof classified as Grade "27" and up under the Compensation and Position Classification Act of 1989; (3) Members of the judiciary without prejudice to the provisions of the Constitution; (4) Chairmen and members of Constitutional Commissions, without prejudice to the provisions of the Constitution; and (5) All other national and local officials classified as Grade "27" and higher under the Compensation and Position Classification Act of 1989. b. Other offenses or felonies committed by the public officials and employees mentioned in subsection (a) of this section in relation to their office. c. Civil and criminal cases filed pursuant to and in connection with Executive Order Nos. 1, 2, 14 and 14-A. In cases where none of the principal accused are occupying positions corresponding to salary grade "27" or higher, as prescribed in the said Republic Act No. 6758, or PNP officers occupying the rank of superintendent or higher, or their equivalent, exclusive jurisdiction thereof shall be vested in the proper Regional Trial Court, Metropolitan Trial Court, Municipal Trial Court, and Municipal Circuit Trial Court, as the case may be, pursuant to their respective jurisdiction as provided in Batas Pambansa Blg. 129.10 On July 10, 1995, petitioner filed with the Sandiganbayan, Third Division, a motion to dismiss or transfer Criminal Case No. 19763 to the Regional Trial Court, Sindangan, Zamboanga. On the same date, petitioner filed with the Sandiganbayan, First Division, a motion to refer Criminal Case No. 22655 to the Regional Trial Court, Sindangan, Zamboanga.

Petitioner averred that the enactment of Republic Act No. 7975 divested the Sandiganbayan of its jurisdiction over criminal cases against municipal mayors for violations of Republic Act No. 3019, as amended, who receive salary less than that corresponding to Grade 27, pursuant to the Index of Occupational Services prepared by the Department of Budget and Management (DBM). On September 7, 1995, the Sandiganbayan, First Division11 denied the motion to refer Criminal Case No. 22655 to the Regional Trial Court. On October 10, 1995, the Sandiganbayan denied petitioner's motion for reconsideration.12 On September 14, 1995, Sandiganbayan, Third Division13 also denied the motion to transfer Criminal Case No. 19763 to the Regional Trial Court. Hence, petitioner filed these petitions for certiorari.14 On December 27, 1995, the Court consolidated the two cases.15 On February 23, 1997, Congress enacted Republic Act No. 8249, an act redefining the jurisdiction of Sandiganbayan.16 On September 1, 1999, we gave due course to the petitions.17 The issue raised in these two cases is whether or not Republic Act No. 7975 divested the Sandiganbayan of its jurisdiction over violations of Republic Act No. 3019, as amended, against municipal mayors. We have resolved this issue in recent cases ruling that the Sandiganbayan has jurisdiction over violations of Republic Act No. 3019, as amended, against municipal mayors.18 There is no merit to petitioner's averment that the salary received by a public official dictates his salary grade. "On the contrary, it is the official's grade that determines his or her salary, not the other way around."19 "To determine whether the official is within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan, therefore, reference should be made to Republic Act No. 6758 and the Index of Occupational Services, Position Titles and Salary Grades. An official's grade is not a matter of proof, but a matter of law which the court must take judicial notice."20 Sec. 444 (d) of the Local Government Code provides that "the municipal mayor shall receive a minimum monthly compensation corresponding to Salary Grade twenty-seven (27) as prescribed under Republic Act No. 6758 and the implementing guidelines issued pursuant thereto." Additionally, both the 1989 and 1997 versions of the Index of Occupational Services, Position Titles and Salary Grades list the municipal mayor under Salary Grade 27.21Consequently, the cases against petitioner as municipal mayor for violations of Republic Act No. 3019, as amended, are within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan.1wphi1.nt WHEREFORE, we hereby DISMISS the consolidated petitions at bar, for lack of merit.

G.R. No. 143047

July 14, 2004

RICARDO S. INDING, petitioner, vs. THE HONORABLE SANDIGANBAYAN and THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, respondents.

DECISION

CALLEJO, SR., J.: This is a petition for certiorari under Rule 65 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure for the nullification of the September 23, 1999 Resolution1 of the Sandiganbayan (Second Division), which denied the petitioner's omnibus motion with supplemental motion, and its Resolution dated April 25, 2000, denying the petitioner's motion for the reconsideration of the same. The Antecedents On January 27, 1999, an Information was filed with the Sandiganbayan charging petitioner Ricardo S. Inding, a member of the Sangguniang Panlungsod of Dapitan City, with violation of Section 3(e) of Republic Act No. 3019,2committed as follows: That from the period 3 January 1997 up to 9 August 1997 and for sometime prior or subsequent thereto, in Dapitan City, Philippines, and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the above-named accused Ricardo S. Inding, a high-ranking public officer, being a Councilor of Dapitan City and as such, while in the performance of his official functions, particularly in the operation against drug abuse, with evident bad faith and manifest partiality, did then and there, willfully, unlawfully and criminally, faked buy-bust operations against alleged pushers or users to enable him to claim or collect from the coffers of the city government a total amount of P30,500.00, as reimbursement for actual expenses incurred during the alleged buy-bust operations, knowing fully well that he had no participation in the said police operations against drugs but enabling him to collect from the coffers of the city government a total amount of P30,500.00, thereby causing undue injury to the government as well as the public interest.3 The case was docketed as Criminal Case No. 25116 and raffled to the Second Division of the Sandiganbayan. On June 2, 1999, the petitioner filed an Omnibus Motion4 for the dismissal of the case for lack of jurisdiction over the officers charged or, in the alternative, for the referral of the case either to the Regional Trial Court or the Municipal Trial Court for appropriate proceedings. The petitioner alleged therein that under Administrative Order No. 270 which prescribes the Rules and Regulations Implementing the Local Government Code of 1991, he is a member of the Sangguniang Panlungsod of Dapitan City with Salary Grade (SG) 25. He asserted that under Republic Act No. 7975, which amended Presidential Decree No. 1606, the Sandiganbayan exercises original jurisdiction to try cases involving crimes committed by officials of local government units only if such officials occupy positions with SG 27 or higher, based on Rep. Act No. 6758, otherwise known as the "Compensation and Position Classification Act of 1989." He contended that under Section 4 of P.D. No. 1606, as amended by Section 2 of Rep. Act No. 7975, the RTC, not the Sandiganbayan, has original jurisdiction over the crime charged against him. The petitioner urged the trial court to take judicial notice of Adm. Order No. 270. In its comment on the omnibus motion, the Office of the Special Prosecutor asserted that the petitioner was, at the time of the commission of the crime, a member of the Sangguniang Panlungsod of Dapitan City, Zamboanga del Norte, one of those public officers who, by express provision of Section 4 a.(1)(b) of P.D. No. 1606, as amended by Rep. Act No. 7975,5 is classified as SG 27. Hence, the Sandiganbayan, not the RTC, has original jurisdiction over the case, regardless of his salary grade under Adm. Order No. 270. On September 23, 1999, the respondent Sandiganbayan issued a Resolution denying the petitioner's omnibus motion. According to the court, the Information alleged that the petitioner has a salary grade of 27. Furthermore, Section 2 of Rep. Act No. 7975, which amended Section 4 of P.D. No. 1606, provides that the petitioner, as a member of the Sangguniang Panlungsod of Dapitan City, has a salary grade of 27.6

On October 27, 1999, the petitioner filed a Supplemental Motion to his omnibus motion, 7 citing Rep. Act No. 8294 and the ruling of this Court in Organo v. Sandiganbayan,8 where it was declared that Rep. Act No. 8249, the latest amendment to the law creating the Sandiganbayan, "collated the provisions on the exclusive jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan," and that "the original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan as a trial court was made to depend not on the penalty imposed by law on the crimes and offenses within its jurisdiction but on the rank and salary grade of accused government officials and employees." In the meantime, the petitioner was conditionally arraigned on October 28, 1999 and entered a plea of not guilty.9 On November 18, 1999, the petitioner filed a Motion for Reconsideration of the Sandiganbayan's September 23, 1999 Resolution.10 The motion was, however, denied by the Sandiganbayan in a Resolution promulgated on April 25, 2000.11 Dissatisfied, the petitioner filed the instant petition for certiorari, contending as follows: A. That Republic Act [No.] 8249 which took effect last 05 February 1997 made the jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan as a trial court depend not only on the penalty imposed by law on the crimes and offenses within its jurisdiction but on the rank and salary grade of accused government officials and employees. B. That the ruling of the Supreme Court in "Lilia B. Organo versus The Sandiganbayan and the People of the Philippines," G.R. No. 133535, 09 September 1999, settles the matter on the original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan as a trial court which is over public officials and employees with rank and salary grade 27 and above. The petitioner contends that, at the time the offense charged was allegedly committed, he was already occupying the position of Sangguniang Panlungsod Member I with SG 25. Hence, under Section 4 of Rep. Act No. 8249, amending Rep. Act No. 7975, it is the RTC and not the Sandiganbayan that has jurisdiction over the offense lodged against him. He asserts that under Adm. Order No. 270, 12 Dapitan City is only a component city, and the members of the Sangguniang Panlungsod are classified as Sangguniang Panlungsod Members I with SG 25. Thus, Section 4 a.(1)(b) of P.D. No. 1606, as amended by Section 2 of Rep. Act No. 7975, and retained by Section 4 of Rep. Act No. 8249, does not apply to him. On the other hand, the respondents, through the Office of the Special Prosecutor, contend that Section 4 a.(1)(b) of P.D. No. 1606, as amended by Section 2 of Rep. Act No. 7975, expressly provides that the Sandiganbayan has original jurisdiction over violations of Rep. Act No. 3019, as amended, committed by the members of theSangguniang Panlungsod, without qualification and regardless of salary grade. They argue that when Congress approved Rep. Act No. 7975 and Rep. Act No. 8249, it was aware that not all the positions specifically mentioned in Section 4, subparagraph (1) were classified as SG 27, and yet were specifically included therein, viz: It is very clear from the aforecited provisions of law that the members of the sangguniang panlungsod are specifically included as among those falling within the exclusive original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan. A reading of the aforesaid provisions, likewise, show that the qualification as to Salary Grade 27 and higher applies only to such officials of the executive branch other than the regional director and higher and those specifically enumerated. To rule, otherwise, is to give a different interpretation to what the law clearly is. Moreover, had there been an intention to make Salary Grade 27 and higher as the sole factor to determine the exclusive original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan then the lawmakers could have simply stated that the officials of the executive branch, to fall within the exclusive original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan, should have been occupying the positions with a Salary Grade of 27 and higher. But the express wordings in both RA No. 7975 and RA No. 8249 specifically including the members of the sangguniang panlungsod, among others, as those within the exclusive original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan only means that the said sangguniang members shall be within the exclusive original jurisdiction of the said court regardless of their Salary Grade. In this connection too, it is well to state that the lawmakers are very well aware that not all the positions specifically mentioned as those within the exclusive original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan have a Salary Grade of 27 and higher. Yet, the legislature has explicitly made the officials so enumerated in RA No. 7975 and RA No. 8249 as falling within the exclusive original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan because of the nature of these officials' functions and responsibilities as well as the power they can wield over their respective area of jurisdiction.13 The threshold issue for the Court's resolution is whether the Sandiganbayan has original jurisdiction over the petitioner, a member of the Sangguniang Panlungsod of Dapitan City, who was charged with violation of Section 3(e) of Rep. Act No. 3019, otherwise known as the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act.

The Court rules in the affirmative. Rep. Act No. 7975, entitled "An Act to Strengthen the Functional and Structural Organization of the Sandiganbayan, Amending for that Purpose Presidential Decree No. 1606," took effect on May 16, 1995. Section 2 thereof enumerates the cases falling within the original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan. Subsequently, Rep. Act No. 7975 was amended by Rep. Act No. 8249, entitled "An Act Further Defining the Jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan, Amending for the Purpose Presidential Decree No. 1606, as Amended, Providing Funds Therefor, and for Other Purposes." The amendatory law took effect on February 23, 1997 and Section 4 thereof enumerates the cases now falling within the exclusive original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan. For purposes of determining which of the two laws, Rep. Act No. 7975 or Rep. Act No. 8249, applies in the present case, the reckoning period is the time of the commission of the offense.14 Generally, the jurisdiction of a court to try a criminal case is to be determined by the law in force at the time of the institution of the action, not at the time of the commission of the crime. 15 However, Rep. Act No. 7975, as well as Rep. Act No. 8249, constitutes an exception thereto as it expressly states that to determine the jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan in cases involving violations of Rep. Act No. 3019, the reckoning period is the time of the commission of the offense. This is plain from the last clause of the opening sentence of paragraph (a) of these two provisions which reads: Sec. 4. Jurisdiction. The Sandiganbayan shall exercise [exclusive]16 original jurisdiction in all cases involving: a. Violations of Republic Act No. 3019, as amended, otherwise known as the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, Republic Act No. 1379, and Chapter II, Section 2, Title VII, [Book II]17 of the Revised Penal Code, where one or more of the principal accused are officials occupying the following positions in the government, whether in a permanent, acting or interim capacity, at the time of the commission of the offense: In this case, as gleaned from the Information filed in the Sandiganbayan, the crime charged was committed from the period of January 3, 1997 up to August 9, 1997. The applicable law, therefore, is Rep. Act No. 7975. Section 2 of Rep. Act No. 7975 expanded the jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan as defined in Section 4 of P.D. No. 1606, thus: Sec. 4. Jurisdiction. The Sandiganbayan shall exercise original jurisdiction in all cases involving:18 a. Violations of Republic Act No. 3019, as amended, otherwise known as the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, Republic Act No. 1379, and Chapter II, Section 2, Title VII of the Revised Penal Code,19where one or more of the principal accused are officials occupying the following positions in the government, whether in a permanent, acting or interim capacity, at the time of the commission of the offense: (1) Officials of the executive branch occupying the positions of regional director and higher, otherwise classified as grade 27 and higher, of the Compensation and Position Classification Act of 1989 (Republic Act No. 6758), specifically including: (a) Provincial governors, vice-governors, members of the sangguniang panlalawigan, and provincial treasurers, assessors, engineers, and other provincial department heads; (b) City mayors, vice-mayors, members of the sangguniang panlungsod, city treasurers, assessors, engineers, and other city department heads;20 (c) Officials of the diplomatic service occupying the position of consul and higher; (d) Philippine army and air force colonels, naval captains, and all officers of higher rank; (e) PNP chief superintendent and PNP officers of higher rank;21 (f) City and provincial prosecutors and their assistants, and officials and prosecutors in the Office of the Ombudsman and special prosecutor; (g) Presidents, directors or trustees, or managers of government-owned or controlled corporations, state universities or educational institutions or foundations; (2) Members of Congress and officials thereof classified as Grade "27" and up under the Compensation and Position Classification Act of 1989; (3) Members of the judiciary without prejudice to the provisions of the Constitution;

(4) Chairmen and members of Constitutional Commissions, without prejudice to the provisions of the Constitution; and (5) All other national and local officials classified as Grade "27" and higher under the Compensation and Position Classification Act of 1989. b. Other offenses or felonies committed by the public officials and employees mentioned in subsection (a) of this section in relation to their office.22 c. Civil and criminal cases filed pursuant to and in connection with Executive Order Nos. 1, 2, 14 and 14A. In cases where none of the principal accused are occupying positions corresponding to salary grade "27" or higher, as prescribed in the said Republic Act No. 6758, or PNP officers occupying the rank of superintendent or higher, or their equivalent, exclusive jurisdiction thereof shall be vested in the proper Regional Trial Court, Metropolitan Trial Court, Municipal Trial Court, and Municipal Circuit Trial Court, as the case may be, pursuant to their respective jurisdiction as provided in Batas Pambansa Blg. 129.23 A plain reading of the above provision shows that, for purposes of determining the government officials that fall within the original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan in cases involving violations of Rep. Act No. 3019 and Chapter II, Section 2, Title VII of the Revised Penal Code, Rep. Act No. 7975 has grouped them into five categories, to wit: (1) Officials of the executive branch occupying the positions of regional director and higher, otherwise classified as grade 27 and higher. . . (2) Members of Congress and officials thereof classified as Grade "27" and up under the Compensation and Position Classification Act of 1989; (3) Members of the judiciary without prejudice to the provisions of the Constitution; (4) Chairmen and members of Constitutional Commissions, without prejudice to the provisions of the Constitution; and (5) All other national and local officials classified as Grade "27" and higher under the Compensation and Position Classification Act of 1989. With respect to the first category, i.e., officials of the executive branch with SG 27 or higher, Rep. Act No. 7975 further specifically included the following officials as falling within the original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan: (a) Provincial governors, vice-governors, members of the sangguniang panlalawigan, and provincial treasurers, assessors, engineers, and other provincial department heads; (b) City mayors, vice-mayors, members of the sangguniang panlungsod, city treasurers, assessors, engineers, and other city department heads; (c) Officials of the diplomatic service occupying the position of consul and higher; (d) Philippine army and air force colonels, naval captains, and all officers of higher rank; (e) PNP chief superintendent and PNP officers of higher rank; (f) City and provincial prosecutors and their assistants, and officials and prosecutors in the Office of the Ombudsman and special prosecutor; (g) Presidents, directors or trustees, or managers of government-owned or controlled corporations, state universities or educational institutions or foundations; The specific inclusion of the foregoing officials constitutes an exception to the general qualification relating to officials of the executive branch as "occupying the positions of regional director and higher, otherwise classified as grade 27 and higher, of the Compensation and Position Classification Act of 1989." In other words, violation of Rep. Act No. 3019 committed by officials in the executive branch with SG 27 or higher, and the officials specifically enumerated in (a) to (g) of Section 4 a.(1) of P.D. No. 1606, as amended by Section 2 of Rep. Act No. 7975,regardless of their salary grades, likewise fall within the original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan. Had it been the intention of Congress to confine the original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan to violations of Rep. Act No. 3019 only to officials in the executive branch with SG 27 or higher, then it could just have ended paragraph (1) of Section 4 a. of P.D. No. 1606, as amended by Section 2 of Rep. Act No. 7975, with the phrase "officials of the executive branch occupying the positions of regional director and

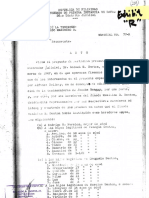

higher, otherwise classified as grade 27 and higher, of the Compensation and Position Classification Act of 1989." Or the category in paragraph (5) of the same provision relating to "[a]ll other national and local officials classified as Grade '27' and up under the Compensation and Classification Act of 1989" would have sufficed. Instead, under paragraph (1) of Section 4 a. of P.D. No. 1606, as amended by Section 2 of Rep. Act No. 7975, Congress included specific officials, without any reference as to their salary grades. Clearly, therefore, Congress intended these officials, regardless of their salary grades, to be specifically included within the Sandiganbayan's original jurisdiction, for had it been otherwise, then there would have been no need for such enumeration. It is axiomatic in legal hermeneutics that words in a statute should not be construed as surplusage if a reasonable construction which will give them some force and meaning is possible.24 That the legislators intended to include certain public officials, regardless of their salary grades, within the original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan is apparent from the legislative history of both Rep. Acts Nos. 7975 and 8249. In his sponsorship speech of Senate Bill No. 1353, which was substantially adopted by both Houses of Congress and became Rep. Act No. 7975, Senator Raul S. Roco, then Chairman of the Committee on Justice and Human Rights, explained: Senate Bill No. 1353 modifies the present jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan such that only those occupying high positions in the government and the military fall under the jurisdiction of the court. As proposed by the Committee, the Sandiganbayan shall exercise original jurisdiction over cases assigned to it only in instances where one or more of the principal accused are officials occupying the positions of regional director and higher or are otherwise classified as Grade 27 and higher by the Compensation and Classification Act of 1989, whether in a permanent, acting or interim capacity at the time of the commission of the offense. The jurisdiction, therefore, refers to a certain grade upwards, which shall remain with the Sandiganbayan. The President of the Philippines and other impeachable officers such as the justices of the Supreme Court and constitutional commissions are not subject to the original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan during their incumbency. The bill provides for an extensive listing of other public officers who will be subject to the original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan. It includes, among others, Members of Congress, judges and justices of all courts.25 More instructive is the sponsorship speech, again, of Senator Roco, of Senate Bill No. 844, which was substantially adopted by both Houses of Congress and became Rep. Act No. 8249. Senator Roco explained the jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan in Rep. Act No. 7975, thus: SPONSORSHIP OF SENATOR ROCO By way of sponsorship, Mr. President we will issue the full sponsorship speech to the members because it is fairly technical may we say the following things: To speed up trial in the Sandiganbayan, Republic Act No. 7975 was enacted for that Court to concentrate on the "larger fish" and leave the "small fry" to the lower courts. This law became effective on May 6, 1995 and it provided a two-pronged solution to the clogging of the dockets of that court, to wit: It divested the Sandiganbayan of jurisdiction over public officials whose salary grades were at Grade "26" or lower, devolving thereby these cases to the lower courts, and retaining the jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan only over public officials whose salary grades were at Grade "27" or higher and over other specific public officials holding important positions in government regardless of salary grade;26 Evidently, the officials enumerated in (a) to (g) Section 4 a.(1) of P.D. No. 1606, amended Section 2 of Rep. Act No. 7975, were specifically included within the original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan because the lawmakers considered them "big fish" and their positions important, regardless of their salary grades. This conclusion is further bolstered by the fact that some of the officials enumerated in (a) to (g) are not classified as SG 27 or higher under the Index of Occupational Services, Position Titles and Salary Grades issued by the Department of Budget and Management in 1989, then in effect at the time that Rep. Act No. 7975 was approved. For example: Category New Position Title Grad e

16. FOREIGN RELATIONS SERVICE Foreign Service Foreign Service Officer, Foreign Service Officer, Class II27 Class I29

2328 2430

18. EXECUTIVE SERVICE Local Executives City Government Department Head City Government Department Head I II

2431 2632

Provincial Government Department Head

2533

City Vice Mayor City Vice Mayor City Mayor City Mayor 19. LEGISLATIVE SERVICE Sangguniang Members Sangguniang Panlungsod Member Sangguniang Panlungsod Member Sangguniang Panlalawigan Member Office of the City and Provincial Prosecutors36 Prosecutor Prosecutor Prosecutor Prosecutor IV III II I 29 28 27 26 I II 25 27 2635 I II I II 26 28 2834 30

Noticeably, the vice mayors, members of the Sangguniang Panlungsod and prosecutors, without any distinction or qualification, were specifically included in Rep. Act No. 7975 as falling within the original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan. Moreover, the consuls, city department heads, provincial department heads and members of theSangguniang Panlalawigan, albeit classified as having salary grades 26 or lower, were also specifically included within the Sandiganbayan's original jurisdiction. As correctly posited by the respondents, Congress is presumed to have been aware of, and had taken into account, these officials' respective salary grades when it deliberated upon the amendments to the Sandiganbayan jurisdiction. Nonetheless, Congress passed into law Rep. Act No. 7975, specifically including them within the original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan. By doing so, it obviously intended cases mentioned in Section 4 a. of P.D. No. 1606, as amended by Section 2 of Rep. Act No. 7975, when committed by the officials enumerated in (1) (a) to (g) thereof, regardless of their salary grades, to be tried by the Sandiganbayan. Indeed, it is a basic precept in statutory construction that the intent of the legislature is the controlling factor in the interpretation of a statute.37 From the congressional records and the text of Rep. Acts No. 7975 and 8294, the legislature undoubtedly intended the officials enumerated in (a) to (g) of Section 4 a. (1) of P.D. No. 1606, as amended by the aforesaid subsequent laws, to be included within the original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan. Following this disquisition, the paragraph of Section 4 which provides that if the accused is occupying a position lower than SG 27, the proper trial court has jurisdiction,38 can only be properly interpreted as applying to those cases where the principal accused is occupying a position lower than SG 27 and not among those specifically included in the enumeration in Section 4 a. (1)(a) to (g). Stated otherwise, except for those officials specifically included in Section 4 a. (1) (a) to (g), regardless of their salary grades, over whom the Sandiganbayan has jurisdiction, all other public officials below SG 27 shall be under the jurisdiction of the proper trial courts "where none of the principal accused are occupying positions corresponding to SG 27 or higher." By this construction, the entire Section 4 is given effect. The cardinal rule, after all, in statutory construction is that the particular words, clauses and phrases should not be studied as detached and isolated expressions, but the whole and every part of the statute must be considered in fixing the meaning of any of its parts and in order to produce a harmonious whole. 39 And courts should adopt a construction that will give effect to every part of a statute, if at all possible. Ut magis valeat quam pereat or that construction is to be sought which gives effect to the whole of the statute its every word.40 In this case, there is no dispute that the petitioner is a member of the Sangguniang Panlungsod of Dapitan City and he is charged with violation of Section 3 (e) of Rep. Act No. 3019. Members of the Sangguniang Panlungsodare specifically included as among those within the original jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan in Section 4 a.(1) (b) of P.D. No. 1606, as amended by Section 2 of Rep. Act No. 7975,41 or even Section 4 of Rep. Act No. 824942 for that matter. The Sandiganbayan, therefore, has original jurisdiction over the petitioner's case docketed as Criminal Case No. 25116. IN LIGHT OF ALL THE FOREGOING, the petition is DISMISSED. The Resolutions of the Sandiganbayan dated September 23, 1999 and April 25, 2000 are AFFIRMED. No costs. SO ORDERED.

[G.R. No. 158187. February 11, 2005] MARILYN GEDUSPAN and DRA. EVANGELYN FARAHMAND, petitioners, vs. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES and SANDIGANBAYAN,respondents. DECISION CORONA, J.: Does the Sandiganbayan have jurisdiction over a regional director/manager of government-owned or controlled corporations organized and incorporated under the Corporation Code for purposes of RA 3019, the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act? Petitioner Marilyn C. Geduspan assumes a negative view in the instant petition for certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court. The Office of the Special Prosecutor contends otherwise, a view shared by the respondent court. In the instant Rule 65 petition for certiorari with prayer for a writ of preliminary injunction and/or issuance of a temporary restraining order, Geduspan seeks to annul and set aside the resolutions [1] dated January 31, 2003 and May 9, 2003 of the respondent Sandiganbayan, Fifth Division. These resolutions denied her motion to quash and motion for reconsideration, respectively. On July 11, 2002, an information docketed as Criminal Case No. 27525 for violation of Section 3(e) of RA 3019, as amended, was filed against petitioner Marilyn C. Geduspan and Dr. Evangeline C. Farahmand, Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (Philhealth) Regional Manager/Director and Chairman of the Board of Directors of Tiong Bi Medical Center, Tiong Bi, Inc., respectively. The information read: That on or about the 27th day of November, 1999, and for sometime subsequent thereto, at Bacolod City, province of Negros Occidental, Philippines, and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, abovenamed accused MARILYN C. GEDUSPAN, a public officer, being the Regional Manager/Director, of the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation, Regional office No. VI, Iloilo City, in such capacity and committing the offense in relation to office, conniving, confederating and mutually helping with DR. EVANGELINE C. FARAHMAND, a private individual and Chairman of the Board of Directors of Tiong Bi Medical Center, Tiong Bi, Inc., Mandalangan, Bacolod City, with deliberate intent, with evident bad faith and manifest partiality, did then and there wilfully, unlawfully and feloniously release the claims for payments of patients confined at L.N. Memorial Hospital with Philippine Health Insurance Corp., prior to January 1, 2000, amounting to NINETY ONE THOUSAND NINE HUNDRED FIFTY-FOUR and 64/100 (P91,954.64), Philippine Currency, to Tiong Bi Medical Center, Tiong Bi, Inc. despite clear provision in the Deed of Conditional Sale executed on November 27, 1999, involving the sale of West Negros College, Inc. to Tiong Bi, Inc. or Tiong Bi Medical Center, that the possession, operation and management of the said hospital will be turned over by West Negros College, Inc. to Tiong Bi, Inc. effective January 1, 2000, thus all collectibles or accounts receivable accruing prior to January 1, 2000 shall be due to West Negros College, Inc., thus accused MARILYN C. GEDUSPAN in the course of the performance of her official

functions, had given unwarranted benefits to Tiong Bi, Inc., Tiong Bi Medical Center, herein represented by accused DR. EVANGELINE C. FARAHMAND, to the damage and injury of West Negros College, Inc. CONTRARY TO LAW. Both accused filed a joint motion to quash dated July 29, 2002 contending that the respondent Sandiganbayan had no jurisdiction over them considering that the principal accused Geduspan was a Regional Director of Philhealth, Region VI, a position classified under salary grade 26. In a resolution dated January 31, 2003, the respondent court denied the motion to quash. The motion for reconsideration was likewise denied in a resolution dated May 9, 2003. Hence, this petition. Petitioner Geduspan alleges that she is the Regional Manager/Director of Region VI of the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (Philhealth). However, her appointment paper and notice of salary adjustment[2] show that she was appointed as Department Manager A of the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (Philhealth) with salary grade 26. Philhealth is a government owned and controlled corporation created under RA 7875, otherwise known as the National Health Insurance Act of 1995. Geduspan argues that her position as Regional Director/Manager is not within the jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan. She cites paragraph (1) and (5), Section 4 of RA 8249 which defines the jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan: Section 4. Jurisdiction. The Sandiganbayan shall exercise original jurisdiction in all cases involving: a. Violations of Republic Act No. 3019, as amended, otherwise known as the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, Republic Act No. 1379, and Chapter II, Section 2, Title VII, Book of the Revised Penal Code, where one or more of the accused are officials occupying the following positions in the government, whether in a permanent, acting or interim capacity, at the time of the commission of the offense: (1) Officials of the executive branch occupying the positions of regional director and higher, otherwise classified as Grade 27 and higher, of the Compensation and Position Classification Act of 1989 (Republic Act No. 6758); specifically including; xxx xxx xxx

(5) All other national and local officials classified as Grade 27 and higher under the Compensation and Position Classification Act of 1989. The petition lacks merit. The records show that, although Geduspan is a Director of Region VI of the Philhealth, she is not occupying the position of Regional Director but that of Department Manager A, hence, paragraphs (1) and (5) of Section 4 of RA 8249 are not applicable. It is petitioners appointment paper and the notice of salary adjustment that determine the classification of her position, that is, Department Manager A of Philhealth. Petitioner admits that she holds the position of Department Manager A of Philhealth. She, however, contends that the position of Department Manager A is classified under salary grade 26 and therefore outside the jurisdiction of respondent court. She is at present assigned at the Philhealth Regional Office VI as Regional Director/Manager. Petitioner anchors her request for the issuance of a temporary restraining order on the alleged disregard by respondent court of the decision of this Court in Ramon Cuyco v. Sandiganbayan.[3] However, the instant case is not on all fours with Cuyco. In that case, the accused Ramon Cuyco was the Regional Director of the Land Transportation Office (LTO), Region IX, Zamboanga City, but at the time of the commission of the crime in 1992 his position of Regional Director of LTO was classified as Director II with salary grade 26. Thus, the Court ruled that the Sandiganbayan had no jurisdiction over his person. In contrast, petitioner held the position of Department Director A of Philhealth at the time of the commission of the offense and that position was among those enumerated in paragraph 1(g), Section 4a of RA 8249 over which the Sandiganbayan has jurisdiction: Section 4. Section 4 of the same decree is hereby further amended to read as follows: Section 4. Jurisdiction. The Sandiganbayan shall exercise original jurisdiction in all cases involving: a. Violations of Republic Act No. 3019, as amended, otherwise known as the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, Republic Act No. 1379, and Chapter II, Section 2, Title VII, Book II of the Revised Penal

Code, where one or more of the accused are officials occupying the following positions in the government, whether in a permanent, acting or interim capacity, at the time of the commission of the offense; (1) Officials of the executive branch occupying the positions of regional director and higher, otherwise classified as Grade Grade 27 and higher, of the Compensation and Position Classification Act of 1989 (Republic Act No. 6758), specifically including: (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) (f) xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx

(g) Presidents, directors or trustees, or managers of government-owned and controlled corporations, state universities or educational institutions or foundations. (Underscoring supplied). It is of no moment that the position of petitioner is merely classified as salary grade 26. While the first part of the abovequoted provision covers only officials of the executive branch with the salary grade 27 and higher, the second part thereof specifically includes other executive officials whose positions may not be of grade 27 and higher but who are by express provision of law placed under the jurisdiction of the said court. Hence, respondent court is vested with jurisdiction over petitioner together with Farahmand, a private individual charged together with her. The position of manager in a government-owned or controlled corporation, as in the case of Philhealth, is within the jurisdiction of respondent court. It is the position that petitioner holds, not her salary grade, that determines the jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan. This Court in Lacson v. Executive Secretary, et al. [4] ruled: A perusal of the aforequoted Section 4 of R.A. 8249 reveals that to fall under the exclusive jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan, the following requisites must concur: (1) the offense committed is a violation of(a) R.A. 3019, as amended (the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act), (b) R.A. 1379 (the law on illgotten wealth), (c) Chapter II, Section 2, Title VII, book II of the Revised Penal Code (the law on bribery), (d) Executive Order Nos. 1,2, 14 and 14-A, issued in 1986 (sequestration cases), or (e) other offenses or felonies whether simple or complexed with other crimes; (2) the offender committing the offenses in items (a), (b), (c) and (e) is a public official or employee holding any of the positions enumerated in paragraph a of section 4; and (3) the offense committed is in relation to the office. To recapitulate, petitioner is a public officer, being a department manager of Philhealth, a governmentowned and controlled corporation. The position of manager is one of those mentioned in paragraph a, Section 4 of RA 8249 and the offense for which she was charged was committed in relation to her office as department manager of Philhealth. Accordingly, the Sandiganbayan has jurisdiction over her person as well as the subject matter of the case. WHEREFORE, petition is hereby DISMISSED for lack of merit. Costs against petitioner. SO ORDERED.

[G.R. Nos. 146646-49. March 11, 2005] ROGELIO M. ESTEBAN, petitioner, vs. THE SANDIGANBAYAN and THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, respondent. DECISION SANDOVAL-GUTIERREZ, J.: Before us is a petition for certiorari under Rule 65 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, as amended, assailing the Resolution[1] dated December 18, 2000 of the Sandiganbayan (1st Division) and Order[2] dated January 11, 2000 in Criminal Cases Nos. 24703-04. The instant petition stemmed from the sworn complaint[3] of Ana May V. Simbajon against Judge Rogelio M. Esteban, filed with the Office of the City Prosecutor, Cabanatuan City on September 8, 1997, docketed as I.S. Nos. 9-97-8239. In her complaint, Ana May alleged that she was a casual employee of the City Government of Cabanatuan City. Sometime in February 1997, she was detailed with the Municipal Trial Court in Cities (MTCC), Branch 1, Cabanatuan City, upon incessant request of Presiding Judge Reogelio Esteban, herein petitioner. After her detail with Branch 1, the item of bookbinder became vacant. Thus, she applied for the position but petitioner did not take any action on her application. On July 25, 1997, when she approached petitioner in his chambers to follow up her application, he told her, Ano naman ang magiging kapalit ng pagpirma ko rito? Mula ngayon, girlfriend na kita. Araw-araw papasok ka dito sa opisina ko, at araw-araw, isang halik.(What can you offer me in exchange for my signature? From now on, you are my girlfriend. You will enter this office everyday and everyday, I get one kiss.)[4] Ana May refused to accede to his proposal as she considered him like her own father. Petitioner nonetheless recommended her for appointment. Thereafter, he suddenly kissed her on her left cheek. She was shocked and left the chambers, swearing never to return or talk to petitioner. On August 5, 1997, at around 9:30 in the morning, Virginia S. Medina, court interpreter, informed Ana May that petitioner wanted to see her in his chambers regarding the payroll. As a subordinate, she complied. Once inside, petitioner asked her if she has been receiving her salary as a bookbinder. When she answered in the affirmative, he said, Matagal na pala eh, bakit hindi ka pumapasok dito sa kuwarto ko? Di ba sabi ko say iyo, girlfriend na kita? (So youve been getting the salary for sometime already. Why didnt you report here in my office? Didnt I tell you, youre my girlfriend.)[5] Again, Ana May protested to his proposal, saying he is like a father to her and that he is a married man with two sons.

Petitioner suddenly rose from his seat, grabbed her and said, Hindi pwede yan, mahal kita. (I cant allow that for I love you.) He embraced her, kissing her all over her face and touching her right breast. Ana May freed herself and dashed out of the chambers crying. She threw the payroll on the table of her co-employee, Elizabeth Q. Manubay. The latter sensed something was wrong and accompanied Ana May to the restroom. There she told Elizabeth what happened. On March 9 and July 1, 1998, two Informations for violation of R.A. 7877 (the Anti-Sexual Harassment Law of 1995) were filed against petitioner with the Sandiganbayan, docketed therein as Criminal Cases Nos. 24490 and 24702. Also on July 1, 1998, two Informations for acts of lasciviousness were filed with the same court, docketed as Criminal Cases. 24703-04. On September 18, 1998, petitioner filed a motion to quash the Informations in Criminal Cases Nos. 24703-04 for acts of lasciviousness on the ground that he has been placed four (4) times in jeopardy for the same offense. The Sandiganbayan denied the motion to quash but directed the prosecution to determine if the offenses charged in Criminal Cases Nos. 24703-04 were committed in relation to petitioners functions as a judge. On September 3, 1999, the prosecution filed Amended Informations in Criminal Cases Nos. 24703 and 24704 quoted as follows: Criminal Case No. 24703: That on or about the 5th day of August 1997 in Cabanatuan City, Nueva Ecija, Philippines and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the above-named accused, JUDGE ROGELIO M. ESTEBAN, a public officer, being then the Presiding Judge of Branch 1 of the Municipal Trial Court in Cabanatuan City, who after having been rejected by the private complainant, Ana May V. Simbajon, of his sexual demands or solicitations to be his girlfriend and to enter his room daily for a kiss as a condition for the signing of complainants permanent appointment as a bookbinder in his Court, thus in relation to his office or position as such, with lewd design and malicious desire, did then and there willfully, unlawfully and feloniously planted a kiss on her left cheek against her will and consent, to her damage and detriment. CONTRARY TO LAW.[6] Criminal Case No. 24704 That on or about the 25th day of June 1997 in in Cabanatuan City, Nueva Ecija, Philippines and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the above-named accused, JUDGE ROGELIO M. ESTEBAN, a public officer, being then the Presiding Judge of Branch 1 of the Municipal Trial Court in Cabanatuan City, who after having been rejected by the private complainant, Ana May V. Simbajon, of his sexual demands or solicitations to be his girlfriend and to enter his room daily for a kiss as a condition for the signing of complainants permanent appointment as a bookbinder in his Court, thus in relation to his office or position as such, with lewd design and malicious desire, did then and there willfully, unlawfully and feloniously planted a kiss on her left cheek against her will and consent, to her damage and detriment. CONTRARY TO LAW.[7] On September 29, 1999, petitioner filed a motion to quash the Amended Informations on the ground that the Sandiganbayan has no jurisdiction over the crimes charged considering that they were not committed in relation to his office as a judge. On November 22, 1999, before the Sandiganbayan could resolve the motion to quash, the prosecution filed the following Re-Amended Information in Criminal Case No. 24703: That on or about the 5th day of August 1997 in Cabanatuan City, Nueva Ecija, Philippines and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the above-named accused, JUDGE ROGELIO M. ESTEBAN, a public officer, being then the Presiding Judge of Branch 1 of the Municipal Trial Court in Cabanatuan City, who after having been rejected by the private complainant, Ana May V. Simbajon, of his sexual demands or solicitations to be his girlfriend and to enter his room daily for a kiss as a condition for the signing of complainants permanent appointment as a bookbinder in his Court, thus in relation to his office or position as such, with lewd design and malicious desire, did then and there willfully, unlawfully and feloniously grab private complainant, kiss her all over her face and touch her right breast against her will and consent, to her damage and detriment. CONTRARY TO LAW.[8] which was admitted by the Sandiganbayan.

On December 18, 2000, the Sandiganbayan denied petitioners motion to quash the Amended Informations, holding that the act of approving or indorsing the permanent appointment of complaining witness was certainly a function of the office of the accused so that his acts are, therefore, committed in relation to his office.[9] Petitioner then moved for a reconsideration, but was denied by the Sandiganbayan in its Order dated January 11, 2001. Hence, the instant petition for certiorari. The sole issue for our resolution is whether the Sandiganbayan has jurisdiction over Criminal Cases Nos. 24703-04 for acts of lasciviousness filed against petitioner. Petitioner contends that the alleged acts of lasciviousness were not committed in relation to his office as a judge; and the fact that he is a public official is not an essential element of the crimes charged. The Ombudsman, represented by the Office of the Special Prosecutor, maintains that the allegations in the two (2) Amended Informations in Criminal Cases Nos. 24703-04 indicate a close relationship between petitioners official functions as a judge and the commission of acts of lasciviousness. The petition is bereft of merit. Section 4 of Presidential Decree No. 1606, as amended by Republic Act No. 8249,[10] reads in part: SEC. 4. Jurisdiction. The Sandiganbayan shall exercise exclusive original jurisdiction in all cases involving: xxx b. Other offenses or felonies whether simple or complexed with other crime committed by the public officials and employees mentioned in subsection a of this section in relation to their office. In People v. Montejo,[11] we ruled that an offense is said to have been committed in relation to the office if the offense is intimately connected with the office of the offenderand perpetrated while he was in the performance of his official functions. This intimate relation between the offense charged and the discharge of official duties must be alleged in the Information.[12] This is in accordance with the rule that the factor that characterizes the charge is the actual recital of the facts in the complaint or information.[13][14] Hence, where the information is wanting in specific factual averments to show the intimate relationship/connection between the offense charged and the discharge of official functions, the Sandiganbayan has no jurisdiction over the case. Under Supreme Court Circular No. 7 dated April 27, 1987,[15] petitioner, as presiding judge of MTCC, Branch 1, Cabanatuan City, is vested with the power to recommend the appointment of Ana May Simbajon as bookbinder. As alleged in the Amended Informations in Criminal Cases Nos. 24703-04, she was constrained to approach petitioner on June 25, 1997 as she needed his recommendation. But he imposed a condition before extending such recommendation - she should be his girlfriend and must report daily to his office for a kiss. There can be no doubt, therefore, that petitioner used his official position in committing the acts complained of. While it is true, as petitioner argues, that public office is not an element of the crime of acts of lasciviousness, defined and penalized under Article 336 of the Revised Penal Code, nonetheless, he could not have committed the crimes charged were it not for the fact that as the Presiding Judge of the MTCC, Branch I, Cabanatuan City, he has the authority to recommend the appointment of Ana May as bookbinder. In other words, the crimes allegedly committed are intimately connected with his office. The jurisdiction of a court is determined by the allegations in the complaint or information.[16] The Amended Informations in Criminal Cases Nos. 24703-04 contain allegations showing that the acts of lasciviousness were committed by petitioner in relation to his official function. Accordingly, we rule that the Sandiganbayan did not gravely abuse its discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction in admitting the Amended Informations for acts of lasciviousness in Criminal Cases Nos. 24703-04. WHEREFORE, the petition is DISMISSED. The assailed Resolution and Order of the Sandiganbayan dated December 18, 2000 and January 11, 2001, in Criminal Cases Nos. 24703-04 are AFFIRMED. Costs against the petitioner. SO ORDERED.

DINAH C. BARRIGA, petitioner, vs. THE HONORABLE SANDIGANBAYAN (4TH DIVISION) and THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, respondents. DECISION CALLEJO, SR., J.: This is a petition for certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court for the nullification of the Resolution[1] of the Sandiganbayan in Criminal Case Nos. 27435 to 27437 denying the motion to quash the Informations filed by one of the accused, Dinah C. Barriga, and the Resolution denying her motion for reconsideration thereof. The Antecedents On April 3, 2003, the Office of the Ombudsman filed a motion with the Sandiganbayan for the admission of the three Amended Informations appended thereto. The first Amended Information docketed as Criminal Case No. 27435, charged petitioner Dinah C. Barriga and Virginio E. Villamor, the Municipal Accountant and the Municipal Mayor, respectively, of Carmen, Cebu, with malversation of funds. The accusatory portion reads: That in or about January 1996 or sometime prior or subsequent thereto, in the Municipality of Carmen, Province of Cebu, Philippines and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, above-named accused VIRGINIO E. VILLAMOR and DINAH C. BARRIGA, both public officers, being then the Municipal Mayor and Municipal Accountant, respectively, of the Municipality of Carmen, Cebu, and as such, had in their possession and custody public funds amounting to TWENTY- THREE THOUSAND FORTY-SEVEN AND 20/100 PESOS (P23,047.20), Philippine Currency, intended for the payment of Five (5) rolls of Polyethylene pipes to be used in the Corte-Cantumog Water System Project of the Municipality of Carmen, Cebu, for which they are accountable by reason of the duties of their office, in such capacity and committing the offense in relation to office, conniving and confederating together and mutually helping each other, did then and there willfully, unlawfully and feloniously misappropriate, take, embezzle and convert into their own personal use and benefit said amount of P23,047.20, and despite demands made upon them to account for said amount, they have failed to do so, to the damage and prejudice of the government. CONTRARY TO LAW.[2] The inculpatory portion of the second Amended Information, docketed as Criminal Case No. 27436, charging the said accused with illegal use of public funds, reads:

That in or about the month of November 1995, or sometime prior or subsequent thereto, in the Municipality of Carmen, Province of Cebu, Philippines, and within the jurisdiction of the Honorable Court, above-named accused VIRGINIO E. VILLAMOR and DINAH C. BARRIGA, both public officers, being then the Municipal Mayor and Municipal Accountant, respectively, of the Municipality of Carmen, Cebu, and as such, had in their possession and control public funds in the amount of ONE THOUSAND THREE HUNDRED FIVE PESOS (P1,305.00) Philippine Currency, representing a portion of the Central Visayas Water and Sanitation Project Trust Fund (CVWSP Fund) intended and appropriated for the projects classified under Level I and III particularly the construction of Deep Well and Spring Box for Level I projects and construction of water works system for Level III projects of specified barangay beneficiaries/recipients, and for which fund accused are accountable by reason of the duties of their office, in such capacity and committing the offense in relation to office, conniving and confederating together and mutually helping each other, did then and there, willfully unlawfully and feloniously disburse and use said amount of P1,305.00 for the Spring Box of Barangay Natimao-an, Carmen, Cebu, a barangay which was not included as a recipient of CVWSP Trust Fund, thus, accused used said public fund to a public purpose different from which it was intended or appropriated, to the damage and prejudice of the government, particularly the barangays which were CVWSP Trust Fund beneficiaries. CONTRARY TO LAW.[3] The accusatory portion of the third Amended Information, docketed as Criminal Case No. 27437, charged the same accused with illegal use of public funds, as follows: That in or about the month of January 1997, or sometime prior or subsequent thereto, in the Municipality of Carmen, Province of Cebu, Philippines, and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, abovenamed accused Virginio E. Villamor and Dinah C. Barriga, both public officers, being then the Municipal Mayor and Municipal Accountant, respectively, of the Municipality of Carmen, Cebu, and as such, had in their possession and control public funds in the amount of TWO HUNDRED SIXTY-SEVEN THOUSAND FIVE HUNDRED THIRTY-SEVEN and 96/100 (P267,537.96) PESOS, representing a portion of the Central Visayas Water and Sanitation Project Trust Fund (CVWSP Fund), intended and appropriated for the projects classified under Level I and Level III, particularly the construction of Spring Box and Deep Well for Level I projects and construction of water works system for Level III projects of specified barangay beneficiaries/ recipients, and for which fund accused are accountable by reason for the duties of their office, in such capacity and committing the offense in relation to office, conniving and confederating together and mutually helping each other, did then and there willfully, unlawfully and feloniously disburse and use said amount of P267,537.96 for the construction and expansion of Barangay Cantucong Water System, a project falling under Level II of CVWSP, thus, accused used said public funds to a public purpose different from which it was intended and appropriated, to the damage and prejudice of the government, particularly the barangay beneficiaries of Levels I and III of CVWSP. CONTRARY TO LAW.[4] The Sandiganbayan granted the motion and admitted the Amended Informations. The petitioner filed a Motion to Quash the said Amended Informations on the ground that under Section 4 of Republic Act No. 8294, the Sandiganbayan has no jurisdiction over the crimes charged. She averred that the Amended Informations failed to allege and show the intimate relation between the crimes charged and her official duties as municipal accountant, which are conditions sine qua non for the graft court to acquire jurisdiction over the said offense. She averred that the prosecution and the Commission on Audit admitted, and no less than this Court held in Tan v. Sandiganbayan,[5] that a municipal accountant is not an accountable officer. She alleged that the felonies of malversation and illegal use of public funds, for which she is charged, are not included in Chapter 11, Section 2, Title VII, Book II, of the Revised Penal Code; hence, the Sandiganbayan has no jurisdiction over the said crimes. Moreover, her position as municipal accountant is classified as Salary Grade (SG) 24. The petitioner also posited that although the Sandiganbayan has jurisdiction over offenses committed by public officials and employees in relation to their office, the mere allegation in the Amended Informations that she committed the offenses charged in relation to her office is not sufficient as the phrase is merely a conclusion of law; controlling are the specific factual allegations in the Informations that would indicate the close intimacy between the discharge of her official duties and the commission of the offenses charged. To bolster her stance, she cited the rulings of this Court in People v. Montejo,[6] Soller v. Sandiganbayan,[7] and Lacson v. Executive Secretary.[8] She further contended that although the Amended Informations alleged that she conspired with her co-accused to commit the crimes charged, they failed to allege and show her exact participation in the conspiracy and how she committed the crimes charged. She also pointed out that the funds subject of the said Amended Informations were not under her control or administration. On October 9, 2003, the Sandiganbayan issued a Resolution[9] denying the motion of the petitioner. The motion for reconsideration thereof was, likewise, denied, with the graft court holding that the applicable ruling of this Court was Montilla v. Hilario,[10] i.e., that an offense is committed in relation to public office when there is a direct, not merely accidental, relation between the crime charged and the office of the

accused such that, in a legal sense, the offense would not exist without the office; in other words, the office must be a constituent element of the crime as defined in the statute. The graft court further held that the offices of the municipal mayor and the municipal accountant were constituent elements of the felonies of malversation and illegal use of public funds. The graft court emphasized that the rulings of this Court in People v. Montejo[11] and Lacson v. Executive Secretary[12] apply only where the office held by the accused is not a constituent element of the crimes charged. In such cases, the Information must contain specific factual allegations showing that the commission of the crimes charged is intimately connected with or related to the performance of the accused public officers public functions. In fine, the graft court opined, the basic rule is that enunciated by this Court in Montilla v. Hilario, and the ruling of this Court in People v. Montejo is the exception. The petitioner thus filed the instant petition for certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court, seeking to nullify the aforementioned Resolutions of the Sandiganbayan. The petitioner claims that the graft court committed grave abuse of its discretion amounting to excess or lack of jurisdiction in issuing the same. In its comment on the petition, the Office of the Special Prosecutor averred that the remedy of filing a petition for certiorari, from a denial of a motion to quash amended information, is improper. It posits that any error committed by the Sandiganbayan in denying the petitioners motion to quash is merely an error of judgment and not of jurisdiction. It asserts that as ruled by the Sandiganbayan, what applies is the ruling of this Court in Montilla v. Hilario and not People v. Montejo. Furthermore, the crimes of malversation and illegal use of public funds are classified as crimes committed by public officers in relation to their office, which by their nature fall within the jurisdiction of the Sandiganbayan. It insists that there is no more need for the Amended Informations to specifically allege intimacy between the crimes charged and the office of the accused since the said crimes can only be committed by public officers. It further claims that the petitioner has been charged of malversation and illegal use of public funds in conspiracy with Municipal Mayor Virginio E. Villamor, who occupies a position classified as SG 27; and even if the petitioners position as municipal accountant is only classified as SG 24, under Section 4 of Rep. Act No. 8249, the Sandiganbayan still has jurisdiction over the said crimes. The Office of the Special Prosecutor further avers that the petitioners claim, that she is not an accountable officer, is a matter of defense. The Ruling of the Court The petition has no merit. We agree with the ruling of the Sandiganbayan that based on the allegations of the Amended Informations and Rep. Act No. 8249, it has original jurisdiction over the crimes of malversation and illegal use of public funds charged in the Amended Informations subject of this petition. Rep. Act No. 8249,[13] which amended Section 4 of Presidential Decree No. 1606, provides, inter alia, that the Sandiganbayan has original jurisdiction over crimes and felonies committed by public officers and employees, at least one of whom belongs to any of the five categories thereunder enumerated at the time of the commission of such crimes.[14] There are two classes of public office-related crimes under subparagraph (b) of Section 4 of Rep. Act No. 8249: first, those crimes or felonies in which the public office is a constituent element as defined by statute and the relation between the crime and the offense is such that, in a legal sense, the offense committed cannot exist without the office;[15] second, such offenses or felonies which are intimately connected with the public office and are perpetrated by the public officer or employee while in the performance of his official functions, through improper or irregular conduct.[16] The Sandiganbayan has original jurisdiction over criminal cases involving crimes and felonies under the first classification. Considering that the public office of the accused is by statute a constituent element of the crime charged, there is no need for the Prosecutor to state in the Information specific factual allegations of the intimacy between the office and the crime charged, or that the accused committed the crime in the performance of his duties. However, the Sandiganbayan likewise has original jurisdiction over criminal cases involving crimes or felonies committed by the public officers and employees enumerated in Section (a) (1) to (5) under the second classification if the Information contains specific factual allegations showing the intimate connection between the offense charged and the public office of the accused, and the discharge of his official duties or functions - whether improper or irregular.[17] The requirement is not complied with if the Information merely alleges that the accused committed the crime charged in relation to his office because such allegation is merely a conclusion of law.[18] Two of the felonies that belong to the first classification are malversation defined and penalized by Article 217 of the Revised Penal Code, and the illegal use of public funds or property defined and penalized by Article 220 of the same Code. The public office of the accused is a constituent element in both felonies. For the accused to be guilty of malversation, the prosecution must prove the following essential elements:

(a) (b) (c)

The offender is a public officer; He has the custody or control of funds or property by reason of the duties of his office; The funds or property involved are public funds or property for which he is accountable; and

(d) He has appropriated, taken or misappropriated, or has consented to, or through abandonment or negligence, permitted the taking by another person of, such funds or property.[19] For the accused to be guilty of illegal use of public funds or property, the prosecution is burdened to prove the following elements: (1) The offenders are accountable officers in both crimes.

(2) The offender in illegal use of public funds or property does not derive any personal gain or profit; in malversation, the offender in certain cases profits from the proceeds of the crime. (3) In illegal use, the public fund or property is applied to another public use; in malversation, the public fund or property is applied to the personal use and benefit of the offender or of another person. [20] We agree with the ruling of the Sandiganbayan that the public office of the accused Municipal Mayor Virginio E. Villamor is a constituent element of malversation and illegal use of public funds or property. Accused mayors position is classified as SG 27. Since the Amended Informations alleged that the petitioner conspired with her co-accused, the municipal mayor, in committing the said felonies, the fact that her position as municipal accountant is classified as SG 24 and as such is not an accountable officer is of no moment; the Sandiganbayan still has exclusive original jurisdiction over the cases lodged against her. It must be stressed that a public officer who is not in charge of public funds or property by virtue of her official position, or even a private individual, may be liable for malversation or illegal use of public funds or property if such public officer or private individual conspires with an accountable public officer to commit malversation or illegal use of public funds or property. In United States v. Ponte,[21] the Court, citing Viada, had the occasion to state: Shall the person who participates or intervenes as co-perpetrator, accomplice or abettor in the crime of malversation of public funds, committed by a public officer, have the penalties of this article also imposed upon him? In opposition to the opinion maintained by some jurists and commentators (among others the learned Pacheco) we can only answer the question affirmatively, for the same reasons (mutatis mutandis) we have already advanced in Question I of the commentary on article 314. French jurisprudence has also settled the question in the same way on the ground that the person guilty of the crime necessarily aids the other culprit in the acts which constitute the crime. (Vol. 2, 4th edition, p. 653) The reasoning by which Groizard and Viada support their views as to the correct interpretation of the provisions of the Penal Code touching malversation of public funds by a public official, is equally applicable in our opinion, to the provisions of Act No. 1740 defining and penalizing that crime, and we have heretofore, in the case of the United States vs. Dowdell (11 Phil. Rep., 4), imposed the penalty prescribed by this section of the code upon a public official who took part with another in the malversation of public funds, although it was not alleged, and in fact clearly appeared, that those funds were not in his hands by virtue of his office, though it did appear that they were in the hands of his coprincipal by virtue of the public office held by him.[22] The Court has also ruled that one who conspires with the provincial treasurer in committing six counts of malversation is also a co-principal in committing those offenses, and that a private person conspiring with an accountable public officer in committing malversation is also guilty of malversation.[23] We reiterate that the classification of the petitioners position as SG 24 is of no moment. The determinative fact is that the position of her co-accused, the municipal mayor, is classified as SG 27, and under the last paragraph of Section 2 of Rep. Act No. 7975, if the position of one of the principal accused is classified as SG 27, the Sandiganbayan has original and exclusive jurisdiction over the offense. We agree with the petitioners contention that under Section 474 of the Local Government Code, she is not obliged to receive public money or property, nor is she obligated to account for the same; hence, she is not an accountable officer within the context of Article 217 of the Revised Penal Code. Indeed, under the said article, an accountable public officer is one who has actual control of public funds or property by reason of the duties of his office. Even then, it cannot thereby be necessarily concluded that a municipal accountant can never be convicted for malversation under the Revised Penal Code. The name or relative importance of the office or employment is not the controlling factor.[24] The nature of the duties of the public officer or employee, the fact that as part of his duties he received public money for which he is bound to account and failed to account for it, is the factor which determines whether or not malversation is committed by the accused public officer or employee. Hence, a mere clerk in the provincial or

municipal government may be held guilty of malversation if he or she is entrusted with public funds and misappropriates the same. IN LIGHT OF ALL THE FOREGOING, the petition is DENIED for lack of merit. Costs against the petitioner. SO ORDERED.