Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

General Motors

Încărcat de

Sandeep S KumarDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

General Motors

Încărcat de

Sandeep S KumarDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

No dawn for Detroit Feb 2nd 2011, 21:35 by R.A.

| WASHINGTON

y y

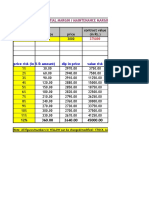

ECONOMISTS have been reading Detroit its last rites for years now. In 2007, economists Ed Glaeser and Giacomo Ponzetto explained how changes in technology destroyed the city's business model, based on the returns to industrial agglomeration. In remarks made while in Stockholm accepting his Nobel prize for work on (among other things) economic geography, Paul Krugman declared that the carmaker bail-out was at best a temporary salve, and that Detroit's car industry was doomed. Ah, but weren't they mistaken! Carmaker output was up over 6% last year, as vehicle sales rose over 13%. In January, vehicle sales returned to preLehman crash levels, and GM sales were up an astounding 22% year-onyear. In Detroit, manufacturing employment has stabilised, and nearly 10,000 manufacturing jobs have been added since the sector hit bottom in mid-2009. And get a load of this: The 10 largest over-the-year jobless rate decreases in December were reported in Michigan areas: Muskegon-Norton Shores (-4.8 percentage points), Monroe (-4.4 points), Jackson (-4.3 points), Flint (-4.2 points), Holland-Grand Haven (-3.9 points), Detroit-Warren-Livonia (-3.8 points), Saginaw-Saginaw Township North (-3.5 points), and Grand RapidsWyoming, Lansing-East Lansing, and Niles-Benton Harbor (-3.4 points each). How wrong could the economists be? There's just one, little problem. Here's total employment for the Detroit metro area over the past decade:

The long decline continues. Well, then why has Detroit's unemployment rate fallen so much? Part of the reason is that the household survey, used to compute the unemployment rate, shows a better employment performance for Detroit over the past year. But the other part of the story is a steady, dramatic decline in the labour force. Since 2007, about 100,000 workers have left the Detroit labour force. And despite the real improvement in the economic outlook over the past few months, the bleeding goes on. What points should we take away from this performance? Well, it may or may not have been a good idea to step in and rescue the carmakers, but the critics who pointed out that it would not save Detroit were right. This should have been obvious at the time, given that it was widely agreed that putting carmakers on a firmer footing would involve drastic cuts to their labour forces and rationalisation of production facilities. A second point follows from this: however strongly America's manufacturing sector rebounds from the crisis and benefits from global rebalancing, it's unreasonable to think that rising manufacturing employment can do much to absorb labour market slack. Manufacturing has only grown less labourintensive over time, and the truly labour-intensive industrial jobs will seek out markets abroad where labour costs are far cheaper than in America. Just as economists pointed out before and during the crisis. It would be too early to write off the Detroit area entirely. As you can see, nearly 1.7m people continue to work in the area. But if Detroit is to thrive again, it will have to discover new and growing industries that depend for their success on the kinds of benefits firms now derive from urban proximity. http://topics.nytimes.com By the time it lost that distinction, such figures were the least of its worries in the fall of 2008, despite two years of steep cutbacks, G.M. found itself on the brink, reduced to begging the federal government for the cash it needed to stay afloat. That December it received $9 billion in federal aid at the order of President George W. Bush. In March 2009, President Obama forced out G.M.'s chief executive, Rick Wagoner, rejected the company's restructuring plan and forced it into bankruptcy court after its creditors balked at deep write-downs. The bankruptcy process was completed on July 10, 2009 when G.M. sold its good assets to a new, government-owned company. Brands like Chevrolet, Cadillac and GMC swere folded into the new company, renamed the General Motors Company. The federal government holds nearly 61 percent of the new company, with the Canadian government, a health care trust for the United Auto Workers union and bondholders owning the balance.

In its new incarnation, the automaker is proving that it can be profitable at a lower sales volume. The company announced in February 2011 that it earned $4.7 billion in 2010, the most in more than a decade. It was the first profitable year since 2004 for G.M., which became publicly traded in November 2010, ending a streak of losses totaling about $90 billion. In addition, G.M. said 45,000 union workers would receive profit-sharing checks averaging $4,300, the most in the companys history. The Beginnings and the Glory Days General Motors was formed on Sept. 16, 1908, when William Crapo Durant filed its incorporation papers, with a revitalized Buick as its foundation. Under the leadership of Alfred P. Sloan Jr., its chief executive from 1923 to 1946, the company revolutionized the field by concentrating on meeting consumer demand by offering, in Sloans words, a car for every purse and purpose.' In the 1950s, with its brands of Chevrolet, Oldsmobile, Pontiac, Cadillac and Buick, General Motors had 46 percent of the American auto market, Ford and Chrysler 44 percent, and everyone else combined just 10 percent. General Motors transformed Detroit into the Silicon Valley of its day, a symbol of America's talent for innovation. It built celebrated cars, like Cadillacs, that became synonymous with luxury. A G.M. plant was a ticket to prosperity for the communities lucky enough to land one. G.M. literally put Spring Hill, Tenn., on the map when it picked the town outside Nashville for its Saturn plant in 1985. Its glory days continued to the 1960s, when it owned half of the United States car and truck market its share peaked at 51 percent in 1962 amid suggestions that it should be broken up under antitrust laws. But then G.M. began a long and slow process of undermining itself. Its strengths, like the rigid structure that provided discipline early on, became weaknesses, and it lost its feel for reading the American car market it helped create, as Japanese automakers lured away even its most loyal buyers. Foreign competition, and G.M.s failures to provide trustworthy cars that Americans wanted, began to diminish its luster and its sales. The Failure to Innovate The company did have vast numbers of loyal buyers, but G.M. lost them through a series of strategic and cultural missteps starting in the 1960s. It bungled efforts in the 1980s to cut costs by sharing the underpinnings of its cars across different brands, blurring their distinctiveness.

G.M. gave in to union demands in 1990 and created a program that paid workers even when plants were not running, forcing it to build cars and trucks it could not sell without big incentives. Its finance staff argued with product developers and marketers who pushed for aggressive spending on new cars and trucks. But forced to feed so many brands, G.M. often resorted to a practice called "launch and leave" - spending billions upfront to bring vehicles to market, but then failing to keep supporting them with sustained advertising. By 1994, when Mr. Wagoner took over as chief executive, its market share had slipped to 33 percent. With its market share shrinking, G.M. could not give its multiple brands and car models the individual attention that helped Honda attract customers to the Accord and Toyota to its Camry. It also lost interest in vehicles that needed time to find their audience, as happened when the company introduced the EV1 electric vehicle and then dropped it in 1999 after only three years. In the early 1990s, the company lagged Chryslers Jeep and Ford by five years in bringing an S.U.V. to market with mass appeal. Once it had ramped up its offerings it also owns Hummer G.M. was reluctant to move from big profitable vehicles to building small, less profitable cars, even when gas prices began a steady rise after 2004. 2007: A Slump Begins And as the price of gasoline at the pump topped $4 a gallon, G.M. was surprised by auto buyers dramatic shift toward the smaller, more fuel-efficient cars and away from the pickups and sport utility vehicles that had served as its mainstay. The company cut its fourth-quarter 2007 production by 10 percent, and by July 2008, overall United States sales had fallen 20 percent. G.M. announced plans to idle plants to address the shrinking demand for pickups and S.U.V.s. At the same time, it was adding shifts to try to make enough small cars. Sales slowed by high gas prices ground to a near-halt as the Wall Street meltdown scared consumers and cut off many from credit. In mid-September 2008, Rick Wagoner, G.M.s chairman, and the heads of Ford and Chrysler went to Washington to ask for $7.5 billion that would support $25 billion in loan guarantees that had been promised to help speed the switch to more efficient cars. The money was approved in October, but not before a dire new forecast for global vehicle sales battered the shares of auto companies, particularly General Motors, whose stock plunged more than 31 percent. G.M. and Chrysler began urgent merger talks, then set those aside as it became clear that neither would survive long without an infusion of cash from the government. Seeking Help From Congress

In November the heads of the Big Three returned to Congress to ask for $25 billion in direct aid, of which $10 billion to $15 billion would go to G.M. After Senate Republicans blocked a bailout bill, President George W. Bush announced an emergency bailout of G.M. and Chrysler. The plan pumped loans of $13.4 billion into Chrysler and G.M. from the fund that Congress authorized to rescue the financial industry. But to secure remaining loans the two companies needed to produce a plan for long-term profitability, including concessions from unions, creditors, suppliers and dealers. The restructuring plan G.M. filed in February said it would need billions in additional government loans, even while cutting jobs, closing plants and reducing their brand lineups. It said it needed $4.6 billion in loans within weeks, from the $18 billion it had already requested, and an additional $12 billion in financial support in order to stave off bankruptcy. On Feb. 26, 2009, General Motors announced that its cash reserves were down to $14 billion at the end of 2008. G.M. lost $30.9 billion, or $53.32 a share, in 2008 and spent $19.2 billion of its cash reserves. Mr. Wagoner met with President Obamas auto task force, and the company said that it could not survive much longer without additional government loans. The Obama Auto Task Force Report In the meantime, the auto task force chosen by President Obama had been delving into every aspect of the companys downsizing plan, including its somewhat upbeat estimate of how the car market will look when the recession ends a market it projects at over 15 million cars annually as well as its designs for new products, its financial controls and its management. Administration officials said the main standard they used to measure the viability of G.M. was the probability of recovering additional taxpayer money used to help the company, should more aid be necessary. On March 29, the task force released its report, which concluded that G.M. had made considerable progress in developing new energy-efficient cars and could survive if it cut costs sharply. President Obama gave G.M. 60 days to present a cost-cutting plan and agreed to provide taxpayer assistance to keep it afloat during that time. Mr. Wagoner resigned as a condition for the Obama administration to continue extending financial aid. Most of the companys board would be replaced over the next few months, under the restructuring plan. Frederick A. Henderson, G.M.s president, succeeded Mr. Wagoner on an interim basis as chief executive. The Detroit-born son of a G.M. sales manager, Mr. Henderson joined G.M. in 1984, became chief financial officer in 2006 and was named president and chief operating officer a year ago. As part of the plan, bondholders were pressed to convert two-thirds of the $27 billion owed them into G.M. stock, while the United Automobile Workers union was asked to substitute stock for 50 percent of their health care benefits for retirees.

Dealership Closings In mid-May, G.M. announced it would eliminate 2,600 of its American dealers, or 40 percent, by 2010. The cuts are meant to thin bloated dealer ranks that are a holdover from the company's better days. The balance of the G.M. cuts will be dealers that sell brands the company is shedding, like Saturn and Hummer, and through attrition. Of the full 2,600 to be cut, 1,100 dealers were notified on May 15. Those 1,100 dealers represent 18 percent of G.M.'s current dealership network but just 7 percent of 2008 sales. Nearly 500 of them sell fewer than 35 new G.M. vehicles a year. Down to the Wire On May 21, G.M. announced that it had reached a deal with the U.A.W., as required by the government, allowing G.M. to finance half of its future retiree health care costs estimated at $20 billion - with company stock. Since G.M. first appealed for government assistance, the U.A.W. has made several modifications to its 2007 contract, including eliminating a program that guarantees paychecks to laid-off workers. Federal and company officials spent May preparing for an increasingly likely bankruptcy filing, which hinged on whether 90 percent of its bondholders would agree to swap the loans for stock in the reorganized company. Advisers to a committee of G.M.'s biggest bondholders, representing about 20 percent of the $27 billion in bond debt, vociferously criticized the plan as unfair and designed to fail. They also accused the government of seeking to use them as scapegoats for a potential bankruptcy filing. Under their own proposal, G.M. bondholders would own 58 percent of the reorganized carmaker. On May 27, G.M. reported that the number of bondholders who had agreed was "substantially less'' than was required. Filing for Bankruptcy On May 31, the government announced that G.M. would file for reorganization in Federal Bankruptcy Court in Manhattan and begin to restructure its troubled operations under government control. With the filing, G.M. followed its crosstown rival Chrysler in bankruptcy. In its bankruptcy petition, G.M. said it had $82.3 billion in assets and $172.8 billion in debts. Its largest creditors were the Wilmington Trust Company, representing a group of bondholders holding $22.8 billion in debts, and affiliates of the United Auto Workers union, representing nearly $20.6 billion in employee obligations. President Obama, speaking on June 1, described the federal officials as "reluctant shareholders,'' but called the bankruptcy and federal aid the only way to avoid an economic calamity.

The company's Saturn unit, which G.M. began in 1990 to compete with foreign-made cars, also filed for bankruptcy. G.M. has said it will phase out the Saturn brand by 2012. G.M.'s Saab unit is already under bankruptcy protection in Sweden. The German government picked Magna International, a Canadian car-parts maker, to buy G.M.'s Opel unit, which is based in Germany. On Nov. 3, 2009, in a reversal, G.M.'s new board said it had decided to keep the European unit because Opel was a critical part of its global vehicle development strategy. In announcing the bankruptcy, Mr. Obama envisioned a much smaller, retooled G.M. can make money even if new car sales remain at a sluggish 10 million a year in the United States and even if G.M., once the giant of the industry, drops below its current 20 percent market share in this country. But to get there, American taxpayers will invest an additional $30 billion in the company, atop $20 billion already spent just to keep it solvent as the company bled cash as quickly as Washington could inject it. Whether that investment will ever be recovered is still an open question, although the president said he was optimistic, and that Washington really had no choice. The New Company Unlike Chrysler, whose reorganization included a challenge by three Indiana state funds that rose to the Supreme Court, G.M. did not face an opponent with enough clout to derail its sale. It faced objections from dissident retail bondholders, who held a fraction of G.M.'s $27 billion in bonds, as well as from accident victim litigants, asbestos claimholders and some retirees whose claims would be largely wiped out. But none of the protests rose higher than Federal District Court, where bankruptcy court rulings are initially appealed. And in the decision approving G.M.'s sale, Judge Robert E. Gerber of Federal Bankruptcy Court said that his ruling relied in part on the precedents set by Chrysler's bankruptcy case a month earlier. On July 10, 2009, G.M. and the government completed the legal paperwork needed to put the company's most desirable assets, including brands like Chevrolet, Cadillac and GMC, into the new company General Motors Company. The new General Motors is selling cars, making money and preparing a public stock offering. But the least valuable assets were left in the shell of the old G.M., called the Motors Liquidation Company. The company has filed a bankruptcy reorganization plan laying out how it will clean up and sell off dozens of unwanted pieces. The biggest challenge is fixing environmental problems at the old plants so they can be put up for sale. Taxpayers are paying for the disposal of the old G.M. properties in the form of a $1.17 billion loan from the Treasury Department. Most of that money, $836 million, will go

toward the cleanup of about 90 plants in 14 states. The bulk of that work should begin by early 2011. A Slow Recovery G.M. said on Nov. 16, 2009, that while it was still losing money, it had stabilized enough that it could take an important symbolic step and begin returning some of the $50 billion that the federal government provided to help with a recovery. On Dec. 1, General Motors announced that Mr. Henderson was resigning and would be succeeded on an interim basis by the automaker's new chairman, Edward E. Whitacre Jr. The company said in January 2010 that Mr. Whitacre would become its permanent chief executive. The new board and Mr. Whitacre previously said they supported Mr. Henderson's efforts. However, there had been questions raised about whether G.M. could overhaul its corporate culture and make a fresh start under a holdover executive like Mr. Henderson, who has worked for the company for 25 years. In February 2010, General Motors announced it would shut down Hummer, the brand of big sport utility vehicles that became synonymous with the term gas guzzler, after a deal to sell it to a Chinese manufacturer fell apart. Over the years, Hummer had shifted from its brawny status to an automotive pariah, one cited as prime evidence of the Detroit automakers failings. In August, G.M. said that it earned $1.3 billion in the second quarter and cited sustained progress in rebuilding operations after emerging from its government-sponsored bankruptcy in 2009. It was G.M.'s second consecutive quarterly profit and paved the way for the automaker for the stock offering in the fall of 2010. In preparation for that move, G.M. said in July 2010 it had agreed to buy a financing company, AmeriCredit, for $3.5 billion so it can lease more vehicles and increase sales to consumers with lower credit ratings. The transaction would give G.M. a captive financing arm for the first time since 2007, when it sold control of GMAC Financial Services. In February 2011, the company reported an annual profit, its first since 2004. GM said it had earned $4.7 billion in 2010. In the fourth quarter of 2010, G.M. earned $510 million, or 31 cents a share, compared with a loss of $3.5 billion in the period the year before. The full-year profit was equal to $2.89 a share. It earned $5.7 billion in 2010 in North America, which had been the biggest source of its pre-bankruptcy troubles. The overall profit was lower in part because of a loss of $1.8 billion in Europe and dividends paid on preferred stock. Revenue was $36.9 billion for the quarter and $135.6 billion for that year.

G.M. said that its board and management team have concluded that the company had resolved material weaknesses in its financial reporting process, a significant concern among analysts. Globally, G.M.s sales rose 12.2 percent in 2010, to 8.39 million, coming within about 30,000 vehicles of retaking the title of worlds largest automaker from Toyota. For the first time, it sold more cars and trucks in China, where its sales rose 28.8 percent from 2009, than in the United States, where sales were up 6.3 percent. The federal government, which exchanged much of the $50 billion it loaned to G.M. for a 61 percent ownership stake, still owns 500 million shares. New Play for Buyers and Investors On Sept. 8, 2010, G.M. rolled out the most significant new-model introduction in the United States since its 2009 bankruptcy, the Chevrolet Cruze. It is the most earnest attempt at building a compact car that Americans might buy because they like it not simply because it is cheap. The reception from consumers could play a large role in wooing potential investors. Overseas, where the Cruze was introduced in 2009, the car is Chevrolets second-bestselling vehicle in 2010, behind the Silverado pickup. But winning over American consumers with a small, fuel-efficient car long the domain of Japanese carmakers like Honda and Toyota has until now mostly eluded Detroit automakers. With a starting price of $16,995, the Cruze costs more than most of its competitors, but G.M. argues that it provides a better value, with amenities like air-conditioning and power locks that are basics in higher-end models but extra on most compacts. That approach helps the Cruze generate more revenue and allows the car to be built profitably at a union plant in the United States. (Most competing compact cars are built at nonunion plants or in other countries.) Hide Company Information General Motors Company (GM) is a global automotive company. The Company develops, produces and markets cars, trucks and parts worldwide. Its business is diversified across products and geographic markets, with operations and sales in over 120 countries. GM assembles its passenger cars, crossover vehicles, light trucks, sport utility vehicles, vans and other vehicles in 71 assembly facilities worldwide and has 87 additional global manufacturing facilities. With a global network of over 21,700 independent dealers it meets the local sales and service needs of its retail and fleet customers. GM's business is organized into three geographically-based segments: General Motors North America (GMNA), General Motors International Operations

(GMIO) and General Motors Europe (GME). It offers a global vehicle portfolio of cars, crossovers and trucks. In addition to the products GM sells to its dealers for consumer retail sales, it also sells cars and trucks to fleet customers. General Motors 300 Renaissance Center 0 Detroit MI 48265-3000 Phone: +1 (313) 556-5000 Fax: n.a. Web site ARTICLES ABOUT GENERAL MOTORS Newest First | Oldest First Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Next >>

G.M. Reports an Annual Profit, Its First Since 2004 By NICK BUNKLEY General Motors said that it earned $4.7 billion in 2010 and that union workers would receive profit-sharing checks of $4,300, the most in the automakers history.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- At Barista LavazzaDocument36 paginiAt Barista LavazzaSandeep S KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Merchant BankingDocument17 paginiMerchant BankinggauravchabukswarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Margin WorkingsDocument3 paginiMargin WorkingsSandeep S KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- GM PPT StyleDocument19 paginiGM PPT StyleSandeep S KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Banking ServicesDocument14 paginiBanking ServicesSandeep S KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Rizwan@Document11 paginiRizwan@Rizwan SohailÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2021 Mobility Strategy and Action PlanDocument26 pagini2021 Mobility Strategy and Action Plandalila almeidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tesla, IncDocument17 paginiTesla, IncSavithri SavithriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clay Modeling, Hu L/N Engineering and Aerodynamics in Passenger Car Body DesignDocument56 paginiClay Modeling, Hu L/N Engineering and Aerodynamics in Passenger Car Body Designveence spenglerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Favorit136l Paper Car PDFDocument1 paginăFavorit136l Paper Car PDFPaul100% (1)

- Toyota ProjectDocument9 paginiToyota ProjectMohemmad NaseefÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of A Remanufacturing For Lithium Ion Batteries From Electric CarsDocument7 paginiEvaluation of A Remanufacturing For Lithium Ion Batteries From Electric CarsKhalid MahmoodÎncă nu există evaluări

- SKU Productivity PDFDocument9 paginiSKU Productivity PDFdreamer4077Încă nu există evaluări

- BUS 5117 WA Unit 7Document6 paginiBUS 5117 WA Unit 7Hassan Suleiman SamsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3.1 Case Study - GCK 1Document1 pagină3.1 Case Study - GCK 1Karim YoussefÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hospitality in The Digital Era Codex2543Document24 paginiHospitality in The Digital Era Codex2543Elena D'PeruccaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mass TransportationDocument20 paginiMass Transportationyoyo_8998Încă nu există evaluări

- Rishabh Jain - Minor Project ReportDocument41 paginiRishabh Jain - Minor Project ReportJaspreet SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Carte Tehnica Fiat Punto EVODocument270 paginiCarte Tehnica Fiat Punto EVOm1tzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Informational Passages RC - CarsDocument1 paginăInformational Passages RC - CarsandreidmannnÎncă nu există evaluări

- P1i4v5ijmfm-Full P - 01-21 Dr. Padma Yallapragada Apr-2017 PDFDocument21 paginiP1i4v5ijmfm-Full P - 01-21 Dr. Padma Yallapragada Apr-2017 PDFSMITHA BABU MBA19-21Încă nu există evaluări

- Electric - Railway - Journal Gull Lake PDFDocument1.293 paginiElectric - Railway - Journal Gull Lake PDFmark_schwartz_41Încă nu există evaluări

- Final Business Plan of Pso in SMDocument30 paginiFinal Business Plan of Pso in SMfraziqurianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Immobilizer: What Is Immobilizer and Why Is It Important?Document6 paginiImmobilizer: What Is Immobilizer and Why Is It Important?mohamedbadawyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Japan's Most Successful Automobile Brand - Case StudyDocument3 paginiJapan's Most Successful Automobile Brand - Case StudyElie Abi JaoudeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elevating The Future of Mobility: Passenger Drones and Flying CarsDocument20 paginiElevating The Future of Mobility: Passenger Drones and Flying CarsKhairul AzmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project Report On REVADocument25 paginiProject Report On REVAmahtaabk100% (1)

- College of Criminal JusticeDocument29 paginiCollege of Criminal JusticeBon ThugsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spinny 2020 Toyota Glanza Inspection ReportDocument1 paginăSpinny 2020 Toyota Glanza Inspection ReportsagarmohanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dissertation DraftDocument3 paginiDissertation DraftSree RamyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3M Franchise ProposalDocument31 pagini3M Franchise ProposalmgroverÎncă nu există evaluări

- CarMaker WhitepaperDocument9 paginiCarMaker WhitepapersegiropiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annotated BibliographyDocument3 paginiAnnotated Bibliographyapi-445103085Încă nu există evaluări

- CRM Initiatives in Hyundai MotorsDocument9 paginiCRM Initiatives in Hyundai MotorsGanesan Gandhi0% (1)

- Ford SwotDocument7 paginiFord SwotKhắc ThànhÎncă nu există evaluări