Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Gothic Leonardo

Încărcat de

Carmi CioniDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Gothic Leonardo

Încărcat de

Carmi CioniDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

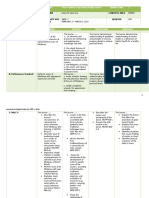

The Gothic Leonardo: Towards a Reassessment of the Renaissance Author(s): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus et Historiae, Vol.

17, No. 34 (1996), pp. 121-158 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1483527 . Accessed: 25/07/2011 12:00

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=irsa. . Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae.

http://www.jstor.org

JOSEPH MANCA

Towards Reassessmentof the Renaissance a The GothicLeonardo:

'The age of chivalryis gone. That of sophisters, economists, and calculatorshas succeeded, and the glory of Europe is extinguished forever. Never, never more shall we behold that generous loyaltyto rank and sex, that proud submission, that digniof fied obedience, that subordination the heart which kept alive, even in servitude itself, the spiritof an exalted freedom." - EdmundBurke, Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790)

INTRODUCTION Leonardo and the Renaissance: Traditional wisdom affirms,and not withoutreason, that art was rebornin the fifteenthand sixteenth centuries, and that an artistic revolution occurred at that time embodying various aspects of classicism and opposing the medieval style. This notion of linear progress and stylisticrevolutionhas clearly been an attractiveone over the years, but the eagerness to see an organic and teleological development in Italianart has helped to discourage investigation of retrospective aspects of Renaissance styles. Historians have exhibited the keenest interest in recording ground-breakingparadigm shifts in Italian painting and sculpture, whereas episodes of conservatism and retrogression have proven

inconvenient to them. Specifically, in the subject treated in this essay, aspects of the late Gothic style that survived well into the Quattrocentoand beyond are often ignored in art historicalliterature. Indeed,the desire to chart progress in art historyhas led to an overelements even in paintingand sculptureof the looking of traditional first part of the fifteenth century. For example, Gothicizing artists such as Gentile da Fabrianoand Antonio Pisanello are frequently discussed less as examples of the elegant International style and more in terms of their naturalismand perceptive observationof the real world, features that the new, renascent art shared with late Gothic painting. Similarly,Masolinoda Panicale's naturalism and his links to Masaccio have capture more attentionthan his conservative aspects, just as Alessandro Botticelli'slinksto humanisticpoetry and philosophy are stressed more often than his traditional stylistic tendencies. Apparently, the movement into new art historicalperiods has captured the imaginationof generations of observers. GiorgioVasarirated Leonardoas one of the leaders of the "third of part" his Lives, and as a pioneer of the Cinquecentostyle. The literature after Vasari indicates this same tendency to stress the progressive aspects of the artist'soeuvre; he is almost always presented as an innovator. To be sure, there have been differing assessments in this regard,with some writersmore willingthan others to stress the traditional aspects of Leonardo'sart, while others, 121

JOSEPH MANCA especially more recent authors, have tended to concentrate attention on his more purely progressive tendencies. But it is worth stressing and elaboratingon the conservative nature of Leonardo's artwork,for however genuinely progressive in many ways, he was as drawnto the past as he was to the call of the future.He preserved the or revived many of the ideals of his predecessors, reformulating canons of beauty of an earlier age, ideals that ultimately originated in an aristocraticworld removed from Leonardo's bourgeois, commercial Florence. One can say that Leonardowas a kind of NeoGothic revivalist,as he freely borrowed aspects of Gothic art and was perfectlyat ease with the essential features of this style. Despite pronouncements by his biographers concerning the revolutionary character of his accomplishments, Leonardo had the grace to link and to himself to a bygone era, to tie himself to a noble tradition, the incorporate old with the new. He established his art, thought,and life-style in a historicalcontinuum and sealed a contract with the past, becoming genuinely progressive by looking backwards. The slightingof this facet of Leonardohas resulted in large part from the prevailing attitude that the Renaissance was essentially to anti-Gothic.Moreover,there is a propensity believe that great personalities, such as Leonardo,not only created and defined art historicalperiods - casting long shadows - but that they only looked forwards.The naturalsciences have progressed throughthe advent of paradigmaticshifts, often brought about by individualgeniuses, and one would apparentlywish to think that art history has developed similarly.But why not instead celebrate Leonardofor his exaltation of the recent past, and for his revival of the artisticgrace, charm, and gentilityof an earlier time? Leonardo embodied such sentiments in his paintingsand drawings,and a look at both his life and art reveals a new Leonardo,a man of the floweringlate Middle Ages, the Gothic Leonardowho found a gracious balance between old and new. In Intentionality: his writings,Leonardohad much to say about art and about methods for makingit. We should, of course, pay heed to these passages when they are relevant. One problem, however, is that his writingshave a differentpurpose and effect than his art, and were producedfor a varietyof scientific,humanistic,and literary contexts. Leonardo's writingsare often relativelycold and abstract, and one frequentlymisses in them the aesthetic sentiments characteristic of his artworks.Freud accurately noted the emotional coolness found in Leonardo'snotebooks and scientifictreatises. In contrast, Leonardoconveys richerand more varied emotional effects in his visual expressions. His writings on shadowing come across overwhelminglyas scientific and calculated directions for rendering three-dimensionality.Leonardothe authorconveys littlesense of the romantic,graceful chiaroscuro effects that he actuallyachieves and upon which a considerablepart of his artisticfame rests. The situation is similarwith his perspective.In the Last Supperthere is a strik122 ing use of single-point perspective as the orthogonals descend abruptlytoward the vanishing point, correct from no point in the room, but conveying a dramaticimpact.One hardlyexpects this kind of emotionalizing effect from the Leonardo whose notebooks emphasize the qualities of illusion, accuracy, and measurement involved in the representationof perspective. Nor does he discuss the signature "mysterious smile"in his writings,which were devoted more to describingthe affettito be employed in convincingnarrative painting.Leonardoas authoroffers littleclue to Mona Lisa's peculiar visage, even despite his writtenattentionto the subtleties of human psychology and emotional expression. It would, of course, be senseless to deny a richcorrespondence between Leonardo's words and his deeds. But to move beyond this kind of correlating,and to avoid the notorious pitfallsthat exist in connecting any artist's writingsto his visual creations, our attention here will fall principally Leonardo'sartworks. on This is not to invoke the tedious postmodern notion that recorded intentionscount for little. Rather it is to say that written intentions and explanations account for only part of the historical truthand, in any case, what is argued here is not the kindof subjecttreatedby Leonardoin his writings. Leonardo could well have had Gothicizing and "antiRenaissance"tendencies even if they did not find a place in his literary output and even if he himself did not always give these tendencies the same conscious attention that his other interests received. Ratherthan look for a correspondencebetween words and images, this essay will treat the writtenword with skepticism - or rather, agnosticism;the art objects will not be gauged by Leonardo's literaryexpression. Similarly,there will be no attemptto exploitthe theme of this essay by documenting the numerous aspects of Leonardo's writingsthat are rooted in medieval optics, naturalhistory, or other sciences. The artistic manifestation of Leonardo's thought will remain the central focus of discussion. Still Gothic:It should not be surprisingthat essential aspects of Gothic style. The late Leonardo's art are linked to the traditional Gothic manner survived into Leonardo's time, even in Florence, in the works of both majorand minorartists. Indeed, there was a curious and strikingGothic revivalbeing carried out in the second half of the Quattrocento in Florence by such artists as Botticelliand Benozzo Gozzoli, a movement abetted by a stylistic conservatism encouraged under Medici patronage. Indeed, some of the elegant and lyricalaspects of the late Gothic mode appeared through the later part of the centuryacross the Italian peninsula,as can be seen in the art of Andrea del Verrocchioin Florence, Giovannidi Paolo in in Siena, Pietro Perugino and BernardinoPinturicchio Umbria,and Baldassare d'Este in Ferrara.When Leonardowent to Milanin the 1480s he would have found there a thrivinglate Gothic style which, even if it did not actively inspire him, would at least not have discouraged any Gothicizing tendencies he possessed. In short, it

THE GOTHICLEONARDO: TOWARDSA REASSESSMENTOF THE RENAISSANCE would not be surprising that an Italian artist, even one born in Tuscany in mid-century,would, like some of his contemporaries, have indulged in borrowing features of the late Gothic manner. Leonardo a Gothicpersonality?:It is difficult demonstrate that to there was such a thing as a "Gothicpersonality," still, it is plaubut, sible to assume that a certaintype of person livingin Italyin the later fifteenthcentury might have been more prone than others to favor a traditionalmode of artmaking. In this sense, one can argue that Leonardo's very personalitywould have led him to choose certain into aspects of the Gothic style for incorporation his art. Beginning with Vasari, Leonardo's biographershave sought to describe his personality: affable with humans, compassionate towards animals, and blessed from Heaven with many gifts, yet a bit eccentric and aloof at times owing to his obsession with scientific problems. Vasari was amazed that in his later years Leonardodid not seek out artisticcommissions, preferring leisure and involvement with his own privateprojects;this disdain for lucrativeartisticwork is fully borne out by the surviving literary and artistic evidence. Certainly anything but an assiduous, bourgeois citizen, Leonardo was less interested in setting up a busy shop and amassing a fortune throughthe marketplacethan in engaging in solitary,intellectual pursuits.Indeed, even as a youth, Leonardodid not rush into the fray of artisticcompetitionin Florence. Evidentlyto the surprise of many modern writers,Leonardo remained in Verrocchio's workshop untilhe was in his mid-twenties, unusuallylong time for a young an man to continue as an assistant or even as a collaborator with his teacher. Perhaps most tellingly all, it was not long before he threw of himself into the employmentof a duke, then a pope, and finallya Leonardo rejected the shop system and comking. In his maturity, mercial world accepted by his Florentinecountrymen,preferring the atmosphere of courts instead. One feels compelled to agree with Kenneth Clark, who noted that Leonardo's personal reserve and mysterious manner made him unsuited for the "Forum life" of Florence. On the matter of the tyrannicalpoliticalarrangementsthat held sway in many parts of Italy,Leonardowas not at all moved to rebel. Neither democrat nor republican,he had little use for the popular revolutionsthat so excited Michelangelo and other contemporaries. On the contrary,Leonardowas comfortablearound despotic leaders such as the dreaded Cesare Borgia, serving him apparentlywithout moral qualm. Leonardo was uninterested in disturbingthe political that he was attractedhis whole life order, and it is hardlysurprising to courts, with their relative stabilityand calm. In short, although a poor burgher,businessman, or democrat, Leonardowas perfectlyat home in a situation of economic, personal, and politicaldependency, where his suave and gracious personalitycould attain its perfect expression. Courtly surroundingswere most suited to him, and it was in the courts that the attitudeand behaviorof aristocratic of life the late medieval world, both in Italyand elsewhere in Europe, was preserved longest. Leonardo da Vinci was drawn to leisure, honor, and servitude, and was likewise at ease with dependence, homage, and hierarchy.He must have fancied himself a good courtierrather than the productof a mercantilesociety, and this has manifestations in his courtlyartisticstyle. He was a failed Florentine indeed, and the wonder felt by Cinquecentowriterssuch as Vasari was an inevitable reactionto the life of one who cared littlefor money and productive work, preferringto spend his time engaging in scientific pursuits, paintingslowly at his own pace, and doodlingvarious ideas such as knot patterns. The retrospectiveaspects of his style, which we will explore presently, are not unlike the regressive circumstances of employmentthat he preferred.Leonardowas not only one of the the first modem men, as is often stated; he was also a marvelous,late encapsulationof the MiddleAges, which in his style flowered anew.

LEONARDO'SPAINTINGS AND DRAWINGS On the surface: At first sight, the task of regardingLeonardoas a late Gothic artist might seem daunting.Afterall, just as his scientific thought was undoubtedlyprogressive and in the avant garde, some of his artworksoffer littlefor the interpretation Leonardoas of a conservativeartist.One will be disappointedin tryingto see in his Last Supper, Saint Jerome (Vatican),or copies and drawingsfor the Battle of Anghiarievidence of a retrospective,late Gothic strain in his artisticthinking,partly because of the stylistic mode that he chose and partlybecause the surface technique is lost to us. Still,there is good reason to see Leonardoas a consciously retrogressive painter. Let us turnfirstto his famous sfumato and morbidezza, his surfaces rendered with a generalized applicationof the brush and toned down with a soft, smoky haze (the two cannot be separated). Leonardohas been creditedwith inventinga new kind of texture, one that differedfrom the earlier Renaissance style pictorial and established an importantaspect of the new High Renaissance manner. Fifteenth-century painters - includingAndrea Mantegna, Andrea del Castagno, and FilippinoLippi - represented things in, as Vasari put it, a dry, hard, stony, and pedantic technique. Later, however, painterssuch as Leonardo,Giorgione,and Correggioused broader strokes, a lighterand more generalized touch, and sfumato to suggest, ratherthan exactly represent, various naturalsurfaces. Of Leonardo(the earliest of these three painters),we might ask whether this was strictlya progressive change. He employed a generalized style, one that, although the High Renaissance is often associated with classicism, was not an antique revival(since ancient technique was essentially unknown, except through verbal descriptions). Rather, Leonardo's style had precedents in late International Gothic painting,the soft, delicate manner that flourishedin the early and middle Quattrocento before the drier style of the Early 123

JOSEPH MANCA

2) Leonardo da Vinci, <<The Virgin and Saint Anne,, Paris, Musee du Louvre. Madonna of Humility,, Paris, Musee 1) Jacopo Bellini, <<The du Louvre.

Renaissance came about as a reaction to the sweet, softer Gothic surfaces. In his suave technique, Leonardowas not buildingon an existing Renaissance tradition,but returing to an earlier, gracious manner used by Masolinoda Panicale, Gentile da Fabriano,Jacopo Bellini, and Antonio Pisanello. Jacopo's Madonna of Humilityof about 1430 [Fig. 1], now in the Louvre,offers a good comparison with Leonardo's works in that museum, which are similarin the soft articulation and suggestive, delicate surfaces of flesh and drapery. Characteristicespecially of his earlier works, Bellini'spaintinghas a 124

generalized epiderm brought about by the delicate transparencies and the subtle, veiled shadows. The work's grainy surface is quite differentfrom the hardertexturefound in the work of artists such as Andrea Mantegna or, to cite a Florentine artist, Antonio del Pollaiuolo. Both Leonardo's generalized touch and the delicate shadowing gently suggest rather than closely define the surface aspects of naturalforms. This, for Leonardo,was an inspiredalteration of the detailed, hard, and descriptivetextures prevalentduring his time. To remarkthat in this idealizingapplicationof pigment Leonardo continues the form and spiritof late Gothic paintingtechnique is not

THE GOTHICLEONARDO: TOWARDSA REASSESSMENTOF THE RENAISSANCE

3) Andrea del Verrocchio and Leonardo da Vinci, <<The Baptism of Christ,, Florence, Uffizi. 4) Detail of Fig. 3. to say that the earlierartistsused the type of sfumato Leonardo later employed. Unlike these painters, Leonardo used oil paint, and he put far more emphasis on shadowing and the representation of than did the late Gothic artists. Still, there is a three-dimensionality softness and pleasingly grainy application of pigment in the Intemational style that Leonardoclearly knew and drew upon for his of the tough, dry manner of his contemporaries.Leonardo's rejection surfaces have a delicacy,morbidezza, and courtlygrace reminiscent of the International Gothic technique. While his contemporaries in Centraland North Italyattemptedto mimicthe stony Antique in their hard contours and sculpturalclarity,Leonardomodeled his art on the suavity and lightness of touch found in the rather unclassical painters of the late Gothic age. High Renaissance painting technique thus has its roots in the Gothic style, and Leonardowas the first to revive the older manner, transforming into moder art. it

Leonardo as "il cortegiano": Vasari thought that, whereas Leonardo's art was soft and relaxed, Quattrocentopainters labored excessively, producing overstudied works that were too dry and detailed. Like the ideal courtierdescribed by Baldassare Castiglione, Leonardodid not seem to exert great effortin his art or in his personal behavior. Castiglione's social ideal was a returnto chivalric forms of behaviorand a rejectionof the ethics essential to the kind of assiduous mercantilesociety that Leonardowould have known in Florence. For his part, Leonardo's apparent avoidance of overexertion can be seen in his social interactions well as in the rendering as of his surfaces, typically soft and generalized, seemingly applied with ease. Moreover, his figural compositions fit together smoothly with the kindof sprezzatura recommended for the good courtier.In 125

JOSEPH MANCA

John the Baptist>, Paris, Musee 6) Leonardo da Vinci, <<Saint du Louvre.

5) Leonardo da Vinci, <Mona Lisa,, Paris, Musee du Louvre. of in art it was a late manifestation standards of behaviorthat existed in earlier aristocratictimes in feudal courts. Leonardo did not need to live in a court to embrace this ideal, for he could already have independently held this attitude; presumably it was his gracious personalitythat led him to embrace courtlyideals and embody them in his artisticstyle as in his own behavior.We might imagine these naturaltendencies in his social that his stay in Milanreinforced as well as in is art, which seems so easy and nonchalant. behavior, The angel in the Uffizi "Baptism'" Giorgio's story is famous: young Leonardo painted one of the two angels in Verrocchio's Baptism of Christ[Figs. 3 and 4] and the apprentice'sfigure is more progressive than the master's To invest the story with greater sig-

The Virginand Saint Anne [Fig. 2], the figures are fused together in an apparently impossible position with smiling ease and graceful charm, corresponding to Castiglione's ideal of nonchalance. Just as Castiglione's ideal was a retur, or rathera continuation, of a long-standing medieval norm, the personal style he recommends corresponds to essential elements of late Gothic art; a courtly attitude of calm, gracefulness, and amicabilityis characteristicof Gothic painting. The ideal of sprezzatura was not late International and Cinquecentocourts. Instead, in life and new to the Quattrocento 126

THE GOTHICLEONARDO: TOWARDSA REASSESSMENTOF THE RENAISSANCE

.~,~ .',2.. ~

~,'T~

" ~'":T.i...-...... . . :ar?rf;~~~~~~~~~' ,

_':"

'."

,.

,...:...z

~ ,~'~

~~~~:'.-..." .." .

~-'...;...,.

~'~:,.'

'~'?

""

....~C

/j

S^\

;; -

7) Leonardo da Vinci, Studies for the "Leda? (drawing),

Windsor, Royal Library.

added that Verrocchioquit paintingupon seeing the nificance, Vasanri

young artist's work. The dramatic contrast between the painted fig-

ures by master and pupil is appraised in the Leonardo literature as the triumphal sign of a new age (High Renaissance) surpassing the old (Early Renaissance). Apart from the hackneyed topos of Verrocchio's turning his brushes over to Leonardo, the story is essentially true, for there is a great difference in style between the younger and the older artist. Sydney Freedberg offers a poignant discussion of this contrast in his Painting in Italy, 1500-1600, arguing that here the spiritis in concert with materialsubstance, and thus High Renaissance classicism is born, recalling the idealism of Greco-Roman art. Let us reconsider the situation. The year is about 1472, the Renaissance"had not yet happened, Botticellihad yet to paint had not Botticelli "HighRenaissance", had

Annunciation>,, Washington, National 8) Jan van Eyck, <<The Gallery of Art. 127

JOSEPH MANCA

9) Paolo Uccello, <<Saint George and the Dragon,, London, National Gallery.

his GothicizingPrimavera and Birthof Venus, and the Gothic style The Tuscan Renaissance continuedto flourishin much of NorthItaly. was well underway, much of it standing in sharp contrast to late Gothic painting, the effects of which lingered in art across Italy. Where is Leonardo positioned in this situation? His angel is decidedly differentfrom the others in Verrocchio's composition, but the novelties are grounded in past art. Verrocchio's nearby angel seems 128

static and prosaically simple; Leonardo's figure is alive and indeed infused with spirit, but in a manner reminiscent of late medieval painting,where angels have an especially vibrantand active form. The delicate blue strands of ribbonthat float behind the angel's head are curvilinear and light. The skin of the angel is soft, suggestive, and fluid. The hair falls in full, delicate curls, and the face of the angel reveals a small pointy chin and tiny lips, facial features char-

THE GOTHICLEONARDO: TOWARDSA REASSESSMENTOF THE RENAISSANCE

10) Antonio Pisanello, <Visionof Saint Eustace)>, London, National Gallery.

acteristic of the InternationalGothic. As in the Gothic manner, Leonardhere strikes a balance between the real and the ideal. The angel's body is twisted and turned, with a kind of organic, rubbery liveliness running throughoutthe form. Furthermore,certain details in are articulated a way that we can associate with late Gothic paintfromthe northof Europe.The beads of glass on the sleeve have ing the delicacy and the studied quality reminiscentof Jan van Eyck's

works, and the clear perspicuous eyes also have an oltremontane, late Gothic feeling. Obviously, Leonardowanted to achieve a new effect here, an escape from the simple poses and pasty technique of Verrocchio. He did so successfully by softening the surfaces, giving a curving sense to the form and ornament, making the physiognomic type more elegant and doll-like, and by endowingthe angel with a final bit 129

JOSEPH MANCA [Fig. 6], and the beautifulLeda [Fig. 7]. Some writershave suggested that these smiles derive from Archaic Greek art, from Eastern prototypes, or from an internallygenerated ideal. It has also been that the kind of smile found in noted, though it needs reiterating, Leonardo's paintings recalls a formula used in High Gothic art already in the thirteenth century, appearing increasingly in later art courtlyGothic style; such a smile is found in Netherlandish of the fifteenth century, includingmemorableexamples in the works of Jan smiles frequentlyin van Eyck [Fig. 8]. The Madonna, in particular, Gothic art of Northern Europe during the centuries preceding Leonardo,as do angels. This motif,derived from the courtlyworld of the Middle Ages, was filled with the spirit of gentility and goodhumored languor that was overturnedin the second quarterof the fifteenth century, when artists became interested in emotional variand biting narrative.Leonardo himself was ety, realisticstory-telling, interestedin these new trends and worked hard on his reprehighly sentations of the affetti. Nevertheless, the smile recurs like a leitmotif in his art. It is tempting to characterize these smiles as typical of the Renaissance and progressive thought, arguing,for example, that the soul of Mona Lsa is manifestingitself in outwardform, and that this of is an example of the humanistideal of the exteriorrepresentation inner states as discussed by Albertiand many others. In another the approach, Freud sought to rationalize smile as a reminiscenceof the artist's mother,an un-arthistoricalexplanationthat overlooks the from which the motif might have sprung. Perhaps we visual tradition will never know the root cause of his choice, but whatever the aetiology of the motif, Leonardohad rediscoveredan older idea - one found in the Gothicera - that suited his needs. The principlebehind Leonardo's smilingfigures is that varietyis sometimes less important than idealism, and that a contented, harmonious motif can be as imposed artistically part of a perfected pictorialvision. The ideal person is relaxed, happy, fullof grace. 11) Franco-Flemish, early fifteenth century, <Profile Portrait of a Lady,, Washington, National Gallery of Art. Chiaroscuro:Lightingin Early Renaissance painting generally that floods the pictorialworld consists of even, strong illumination Fra Angelico, Piero della Francesca, Domenico represented. Veneziano, and others developed a system of (usually) brightlighting based on a careful study of reflected light and color.The resulting impression of this system is one of rationalclarity. Leonardo tured his back on this system to achieve a romantic,mysterious effect with light and dark that is arguablythe most strikingaspect of his style. But, again, precedents for this technique survivedfrom the Gothic era untilhis own lifetime. The melancholy mood that one frequentlyfinds in the paintings of the late Interational style occurs when the dark, dusky background is contrasted with the more brightlylit garments and skin of the highlightedfigures. The backgroundis blackish or darklytoned, while the lit parts have an innerglow. Conservativeworks, like Paolo

of grace also derived from the late medievalworld,that is, the sunny smile. Mona Lisa's smile: If, among Leonardo's creations, only Mona Lisa smiled [Fig. 5], we might seek a single explanation for the expression she bears: that she was being amused by musicians and jesters, that she is an enigma, or that she is simply jocund, as the name Giocondo implies. But Mona Lisa is just one of many smiling figures in Leonardo's oeuvre, a group that includes both Saint Anne and the Virginin the Louvrepainting[Fig. 2], Saint John the Baptist 130

THE GOTHICLEONARDO: TOWARDSA REASSESSMENTOF THE RENAISSANCE

12) Antonio Vivarini, (<TheAdoration of the Kings,, Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Gemaldegalerie.

Uccello's Saint George and the Dragon in London [Fig. 9], comprise this technique of contrastinglightand dark. In late Gothic paintingof the fifteenth century, a shadowy pall often seems to hang over the murky setting, offering an opportunityfor strong tonal contrasts. Such is the case with the romantic,obscure surroundingsfound in Pisanello's Vision of Saint Eustace [Fig. 10], a paintingwhich also shows the characteristic distinction of magical patches of light against the darkersetting. In this work, the effect is not the product of the darkeningof the green pigment (which has occurredto some extent), but of a conscious distinctionbetween the lit skin and other brightsurfaces with a duller,more matte tonalitythat forms the back-

ground. This method of contradistinction occurred frequently in as International Gothic portraiture, seen in a Franco-Flemishlikeness of a lady from the early fifteenthcentury[Fig. 11]. One widely used method to create tonal contrasts in Gothic art is through the use of actual gold. This technique, frowned on by between Albertiin his De pictura, allowed a vivid contradistinction the gold and the surroundingpigmented area, which is frequently dark or otherwise muted. One could cite numerous instances of this contrasting,and one must choose specimens at random. For example, when gold was used for light,as in The Adorationof the Kings from about 1445 [Fig. 12], the contrast between by Antonio Vivarini 131

JOSEPH MANCA

-r ?! ':? 2/

J _ ?. 1.

L

=, *-1 ;, ?? *'Lt-

*t'

?*

,I

?;r" ii

,f -z;E.

--

L I;

''

d'Este,>, Paris, Musee du 13) Antonio Pisanello, <<Ginevra Louvre.

the shadowy field and gilded portionsis particularly striking.The juxtaposition of darker tonalities with bright, burnished gold in these Gothic paintingsforms a kind of naturalchiaroscuro. Leonardo's system, of course, looks differentin many respects from this late Gothic tradition.His light and dark scheme is more three-dimensional and consistent than the ones previously used, of and he avoids using gold, relyinginstead on the application semitransparent oil paints. But despite these variations, Leonardo is faithfulto the spirit of his models and departs from the brightlylit worlds of so many progressive, Quattrocentopainters. The crepuscular mood of Leonardo'schiaroscuroproduces the minorkey of his 132

14) Leonardo da Vinci, <<PointingLady,, (drawing), Windsor, Royal Library.

art, and his magically lit areas of painted flesh recall the juxtaposition of light flesh or gold with a darker ground, as found in the International style [cf. Fig. 13]. The chiaroscuroof Leonardo is late Gothic in mood, form, and emotional attitude, and suggests the melancholy, spiritual style of the waning MiddleAges as much as the brave new world of Renaissance daylight and brightly reflected color.

THE GOTHICLEONARDO: TOWARDSA REASSESSMENTOF THE RENAISSANCE

15) Leonardo da Vinci, <Maiden with a Unicorn), (drawing), Oxford, Ashmolean Museum.

16) Leonardo da Vinci, <(Madonnaand Child,, Munich, Alte Pinakothek.

An enigmatic vision: No one is quite sure why a certainbeautiful lady in a drawingby Leonardois pointing[Fig. 14], but her overall physical form itself carries effective meaning. She is light of foot, and has a great, simple sweeping curve runningthrough her body. Her smiling lips are small, her neck long, and her hair waves in the wind. The lady's garments are light,and they flutteraround her body. She is, in all this, redolentof the Gothicvision, made by an artistwho had studied reality more deeply than any other International artist, and who knew how to blend the spirit of late medievalismwith a knowledge of underlyinganatomy.An element of Hellenismmight be present here, and Leonardowas, as we know, impressed by flutterimage is unthinkable ing Greco-Roman draperies, but this particular withoutthe Gothic precedents that Leonardo knew. This drawing is

a strong reminder of Leonardo's links to traditional, early Quattrocentoart, and helps us to see connections with his other, similarcreations. For example, his delightfuldancing nymphs from a sheet in the Accademia in Venice are an ideal blend of elegant Hellenisticantiquityand nimble, flutteringGothicism.Another sheet, a Maiden with a Unicorn[Fig. 15], contains traditionalizing style as well as a Gothic subject, the heroine gentle and passive and her head tured in a mannered fashion that is reminiscentof past art. The Lowlands and Leonardo's early idealism: The Munich Madonna and Childis a chief work of Leonardo'searly career and is pertinent to this essay for its medievalism [Fig. 16]. There are aspects of oltremontane art of the fifteenthcentury that served to 133

JOSEPH MANCA inspire the harsh and unadored realists in Italyat that time, yet in the Munich panel Leonardo took from northernart not just microscopic realism, but those precious and lovely elements that one associates with the waning MiddleAges: the comfortingsmile of the Virgin, her rounded, Schone-Madonna type, her passive, demure gaze downwards,the overall vibrantlight,the glint of divine spiriton the light-struckcarafe, the domestic tranquillity, delight in the the details of real objects, and the subtle joyfulness embodied in the gentle turs of drapery and the complicated braids in Mary's hairpiece and hair.Together these elements suggest a late Gothic presence likely inspiredby the far north. A refined Leda: The early lessons that Leonardo leared in his borrowingsfrom late Gothic art stayed with him throughouthis life. AlthoughLeonardo altered, sublimated,and submerged these ideals at times, they sprang back to life full-blown later instances. A nowin lost Leda by Leonardois preserved in its general form throughseveral copies that largely agree in the representation the two main of protagonists[cf. Figs. 7 and 17]. The interactionbetween Leda and her suitor is subtle. Unlikemany more vigorous versions of this subject from the Renaissance, Leonardoturns away from narrativeclarity and portrays a gentle and suggestive encounter.The coolness and formalism of Leonardo's Leda have been called Manneristor but proto-Mannerist, there is no reason to look forwardin time, espewhen the linksto more traditional are in evidence. No figure art cially by Leonardo has a more obvious S-curve runningthroughthe form, recalling a widespread Gothic formula. Some have considered Leda's pose to be a kind of abstractstudy of contrapposto, actubut ally her weight does not shift as much as mightbe expected onto the bearing leg. Instead, she is ratherfloating,more in keeping with her mental pose, half-receptive,but also shying away. The two-figure group is full of undulations,and the curvingswan, the swirlingcurls of her hair,and the fluidpose of Leda herself make this a particularly cursive and archaic compositionfor Leonardo.(The intricateknotstudies; cf. Fig. ting of her hair is best seen in autograph,preparatory The artist has also, in a traditionalizing fashion, pushed the fig7.) ures flat up against the picture plane. In short, this paintinghardly deserves to be seen mainly as a precursorto Mannerism,although the formal qualities, the decorativeness, and the aloof narrativeare "mannered." just as these qualitiesseem to presage a later artBut historicalperiod, so too do they look backwardto late Gothic modes and sensibilities.If this pictureis indeed a sign of movement toward a Cinquecento maniera, then the painting forms a connection between that style and pre-Renaissance modes. Drawings and final products: Certain works by Leonardo suggest that he began with a more traditional approach than the one revealed in the final product.It is as if in his drawingshe expressed an ingrained Gothicism, while in the paintings he altered the first 134

Rome, Galleria 17) Copy after Leonardo da Vinci, <<Leda)>, Borghese.

idea to achieve more academic, "Renaissance"results. In this vein one thinksof RudolfWittkower'sobservation that Nicolas Poussin's drawings were more Baroque than the colder and more academically classical final renderings in paint. With the Leda, it appears that Leonardo's drawingsare even more lithe, delicate, and decorative in the faces and headpieces than the copies show of the final product[Figs. 7 and 17]. In a more certain example, unmediatedby and Saint copies, we can see the same phenomemon.For the Virgin Anne in the Louvrethe design by the artistfor the Saint Anne differs from the finished picture[Figs. 2 and 18]. In comparingthe drawing to the painting,Kenneth Clarkthought that Leonardohere sacrificed some "freshness and humanity" the oil painting, but we should in

THE GOTHICLEONARDO: TOWARDSA REASSESSMENTOF THE RENAISSANCE

gJ:: 1,?? r-rE I?IIs '*sr

;?

,. ? n?I-?

'.

I Z

?-

.-.CP.: (a

4:

I :r **r',t ?? b:'' :: . ? r IL?., i '? [--","c ** 'O. .d

"

IkI :L'??; I.;

i;

!?;

'*,...?

??..? ?i.? :?,r, ?????

??1. ?8'?. lft.:5, ?: .?: ..' ;L: 'i: ??[??': "! -t'

of 18) Leonardo da Vinci, <<Head Saint Anne, (drawing), Windsor, Royal Library.

19) Copy after Leonardo da Vinci, <Monster), (drawing), Windsor, Royal Library.

also stress that in the picturethe saint has largelylost the elongated neck, thin lips, and smiling compassion in the eyes, all more closely linked than the picture to Gothic traditions.Leonardo has painted Saint Anne accordingto a more standard idea, althoughthe type in that it bears with late the picture has still not lost the relationship medieval idealism. Monstrousjokes and drawings:Smiling, nonchalant,suave, and idealized types represent only one aspect of Leonardo's late medievalism; his grotesque monstrosities and bestial jokes were also Gothic in spirit.The monsters that he created in his spare time, such as lizards fixed with "dragonwings," were like medieval gar-

they were meant to amaze by goyles. Only superficially frightening, the fantastic ingenuitythat went into their making. The creation of such droleries filled Leonardo's hours later in life, and linkedhim to the fantastic world of terrific marvels and creatures from Gothic architecture,sculpture, and manuscriptilluminations. Some of Leonardo's grotesques were practical jokes, while many more took artisticforms. He drew a wide varietyof monstrosities, such as the one that has sacs hangingfrom his jaw, and horns springingfrom his forehead [Fig. 19]. In his notes he imagineda fantastic creature with "the head of a mastiffor a hound,the eyes of a the cat, the ears of a porcupine, nose of a greyhound,the brow of a Leonardo the temples of an old cock, and the neck of a turtle." lion, 135

JOSEPH MANCA

X . X~.?~ -.,j . . .'X"' . ......) f*7S.. -. ,- -.

j

. .

~,~,:*~r",. ....* - ....

.,W,

of 20) Leonardo da Vinci, <<Study a Dragon,, (drawing), Windsor, Royal Library.

'

"

I ?. .

22) Leonardo da Vinci, (<Caricatureof a Man with Bushy Hair>, (drawing), Malibu, The J. Paul Getty Museum.

..,. :. Q.

21) Leonardo da Vinci, <<Two Dragons, (drawing), Windsor, Royal Library.

enjoyed designing dragons, as one sees in other drawings [Figs. 20 and 21], and other designs show monstrous mixturesof animals and humans. Throughthese chimericalcreations - all jocular,witty,terrible, and ingenious contrivances - Leonardo again stands as a linking agent between the Middle Ages and Cinquecento Mannerism. 136

are often Caricature:Scientific and progressive interpretations for Leonardo's caricatures[Fig. 22]. First,that he saw in the given streets strange looking people, followed them, and recorded their features as they were. This constitutes a naturalisticexplanation. Secondly, caricatures were, according to other arguments, lordly and tongue-in-cheek alterations of reality, evidence of a growing sense of consciousness of man's ability to re-arrange Nature; Leonardowas aware of the power of art itself, and expressed this in his bizarreand fancifulheads. Finally,the caricaturesare sometimes regarded as psychological studies, growing out of his sketches of real individuals,and only becoming caricatures as an outgrowthof his penetratinganalysis of the human psychology. Various artists, including Albrecht Durer, Leonardo, Annibale Carracci,and Gianlorenzo Berini, have been credited with inventing or advancing the art of caricature.Again it is necessary to ask:

THE GOTHICLEONARDO: TOWARDSA REASSESSMENTOF THE RENAISSANCE was there anything retrogressive or retrospective about Leonardo's caricatures? The answer is that they go against the idealizingtendencies of the Renaissance, and, like some of his actual monstrosities, they hark back to an older traditionof dr6leries, gargoyles, grotesques, and wild men... in short, to Gothic fantasy. Indeed, dr6leries appear in Italianmanuscriptsthrough the Quattrocento,especially during the first three-quartersof the century, and Leonardo's of "doodling" his caricatures significantlyplaces them as amusing of marginaliain his works, recallingthe marginalization late medieval caricaturetypes. Leonardodid not shy away from idealism in his art, of course, but there was a part of him that sought the inventiveness, the bizarreness, and the wit found in medieval distortionsof Nature. Clearly, these earlier medieval examples are not always distortions of real types; one is more often struck instead by their caprice and unreal fantasy. A profileof an old lady, wih her juttinglower jaw, flat nose, and absurdly high headpiece, is typical of this kind of imaginative, unnatural invention [Fig. 23]. Similarly,some of his caricatures have the bestial quality reminiscentof his animal grotesques. In his caricatures,we see evidence that Leonardowas lookingbackward to a more free and capricious age. His caricaturesare consciously bizarre, distortingreality and linkinghim with the fantastic and inventivepast. Imaginationand action painting: It could be said that Leonardo when he noted that one developed his own form of "actionpainting" can see battles, strange faces, costumes, and so forthin stains on a wall or in stones with a variegatedpattern,just as one can hear the names of people or familiar words in the sounds of bells. This is a sensuous attitude,the result not only of his genius and artisticability, but also of the qualityof his mind, which was ever ready for the This creative process, based on sense, stimulaplay of imagination. tion and randomness, differs markedly, for example, from the Platonic idealism of Michelangelo's method. It also contradictsthe stereotypicalview of the Renaissance Man as controlled,proud, and rational.Indeed, we might imagine Leonardo as having been satisfied with the creative nature itself of throwingan ink-soakedsponge against a surface, his mind delightingin the flat, amorphous forms that then came to life in the mind'seye as vividshapes. It is not necessary to believe him when he said that this process was largely intended to inspire other, largercompositions. His words suggest an emotional and visceral sensibility. In this creative play, Leonardo again comes across as a medieval man. He delighted in sensuous, decorative surfaces, and marvelous two-dimensionalpatterns, all this appealing to the artist's ingenuum. Here again Leonardo forms a bridge between medieval to Manneristfantasy. Rocky landscapes: Among the most spectacular aspects of in so Leonardo'sstyle are his rockybackgrounds, prominent the Mona 23) Leonardo da Vinci, (Illl-MatchedCouple? (drawing), Windsor, Royal Library. 137

:,

JOSEPH MANCA

24) Leonardo da Vinci, View in the Sala delle Asse, Milan, Castello Sforzesco.

of Lisa, Virgin the Rocks, and elsewhere. These landscapes are usuof ally thoughtto be a reflection his interestin geology, and are thus These mountainsand placed in the context of his scientificproclivities. rocks are related, though, to the fantastic, stylized types found in Gothic illuminations and panel paintings. Marvelous mountains conin tinue to appear in paintingand illumination North Italy,a trendfostered by late Gothic miniaturists active in the later fifteenthcentustill examples of fantasticrocks and mountainscan be found in ry. Earlier landscapes by Pisanello (paintings and medals), Jacopo Bellini [cf. 138

Fig. 1], Masolinoda Panicale, and others from their generation.Even Kenneth Clark, otherwise not disposed to detecting a "Gothic Leonardo,"suggested this connection. He noted that the artist's of mountains are transformations the "fantasticrocks of Hellenistic and medieval tradition," seeing the medievalism as blended with a classical source. It is true that Leonardochanged the late Gothiclegacy left him by infusingit, based on his researches, with a naturalistic and scientificfoundationbased on his field studies, but - as with many of his other medieval borrowings- the spiritof the traditional

THE GOTHICLEONARDO: TOWARDSA REASSESSMENTOF THE RENAISSANCE

25) Leonardo da Vinci, View in the Sala delle Asse, Milan, Castello Sforzesco.

models is still palpablypresent. The sense of fantasy, escapism, and otherwordlinessof Leonardo'srockybackgrounds very much in the is characterof medievalart, and as usual contrastswiththe rational, regular landscape and mountainbackgroundsof those artists, such as Piero della Francesca, who more than Leonardoexemplifya scientific, calculatingattitudetoward the representationof landscape. The "Sala delle Asse": One widely acknowledged aspect of Leonardo as a retrospectiveartist is his Sala delle Asse in Milan.

This room for Lodovicoil Moro in the Castello Sforzesco was decorated by Leonardoin the 1490s in the mannerof an arborealgarden, adorned with trees and knotted, intertwinedropes, the trunks rising up and the branches spreadingout overhead in a mannerthat some have compared to the columns and ribs of Gothic vaulting[Figs. 24 and 25]. Beyond any architectural comparison,the delight in the flat, and intricatedecoration is in the spiritof late medieval art, verdant, recallingmurals, tapestries, and easel paintings.There were numerous precedents for this kind of wall decoration in earlier art. 139

JOSEPH MANCA plexity of Leonardo's own mind, or a reference to the patron.While for some of these interpretations the Sala delle Asse could well contain some truth, it is importantnot to overlook that in creating this chamber Leonardolooked back at a decorative type found frequently enough in North Italyand Norther Europe in the fourteenthand fifteenthcenturies. Despite the scale and some of the dynamic stylistic innovationsthat he employs, Leonardodepicts a traditionalizing arrangement in the Sala delle Asse. His trees are placed rather evenly around the room, and there is a delicately balanced, floating golden rope that laces through and around the branches, reaching the Sforza arms - the iconographichighlightof the sala - in the center of the ceiling. He has not created deep space here, but that was not his goal, and he maintains relativelytwo-dimension and conservative decoration. Even the roots that break forth from the garden rocks on the lowest level, however energized and apparently characteristicof the High Renaissance they appear, recall the whimsical branches and trees that appear in Gothic paintings and manuscriptborders. Whether or not his patrons actually gave him specific instructionsfor paintingsuch a room, Leonardo clearly relished this assignment, and the productmust be counted among the last, great examples of interiorGothic muraldecoration in Italy. Millefleurs:Leonardo's floral creations have come under the as same kind of interpretation the Sala delle Asse: they have been seen as manifestations of Leonardo's naturalistic "de-Gothicized," and scientific interests, and read as pictorialequivalents of literary, to iconographicideas. Yet it is restricting see the richfloweringin the Annunciationin the Uffizi[Fig. 29] as no more than a catalogue of plant forms and an excuse for an encyclopedic display of iconography; they form a beautifulforegroundand are reminiscentof Gothic tapestries and other decorativelyflowered painted works. Even the flowers and plant forms in the Virginof the Rocks in Paris [Fig. 30] recall this earliertradition, one being revived by Botticelliand others at this same time. Of course, Leonardodoes not always paint floral elements as his backsettings, as he also depicts rocky,forbidding drops. Yet, he was attractedto the studies of flowers and plants on a scientific level, and in his art this intellectualinterest manifests itself once again in a late Gothic form. In Leonardo's portraitof Ginevra de' Benci [Fig. 31], he places her before a rich backdropof foliage, a typical late Gothic device utilizedin portraitsby Pisanello and others of his generation [Fig. 13]. Moreover,the spray of juniper and other vegetable elements on the reverse of the panel form a delightfultouch [Fig. 32]. One associates such delicacy and fine qualitywith Europeanpaintingof 1400-1430 both northand south of as the Alps, in manuscriptilluminations well as in panel painting. Geometric games: Leonardo's notebooks, in particular his CodexAtlanticus, are filledwith simple, flat designs of various kinds. Some of the ones that appear most consistentlyin his notebooks are

26) Anonymous, North Italian, mid-fifteenth century, Room of the Sibyls, Ferrara, Casa Romei.

Examples of foliated, trellised rooms in Gothic art of the Trecento and early Quattrocentosurvive in the Palais des Papes in Avignon, the Palazzo Datiniin Prato, and the Casa Romei in Ferrara[Fig. 26], and such rooms were widespread in courtly habitations of North Italy. Because of their location in Florence, especially relevant are chambers in the Palazzo Davanzati,one with two fourteenth-century and knots designs on the walls, and another with foliage and foliage a decorative, angular strapworkpatter on the four walls [Figs. 27 and 28]. Muralpainters of the later fifteenthand sixteenth centuries replaced the earlier verdant chambers with painted, architectonic structures, such as Andrea Mantegna's Camera Picta, which is formed of a framework of fictive classical architecture. As in comprised Mantegna's room, Cinquecento murals characteristically painted architectureand views into the distance, sometimes including narratives set in well-defined space. Leonardo's arboreal room for Ludovico il Moro belongs to the earlier, pre-Renaissance tradition. In the Sala delle Asse, Leonardo has, nonetheless, been here regarded as a Renaissance innovator.He is said to be reviving tree-architecture described by ancient Roman writers,to as primitive be an arboreal scientist, and to have emphasized, in good High Renaissance fashion, the muscular strength of trees as they burst out from rocks and spread forth.Others see the room, which before the heavy-handed restorationsof the nineteenth century was more as linear and obviously intertwined, an intricatesymbol of the com140

THE GOTHICLEONARDO: TOWARDSA REASSESSMENTOF THE RENAISSANCE

27) Anonymous, fourteenth century, bedroom murals, Florence, Palazzo Davanzati (third floor).

designated with various names: curvilateral stars, lunulae, or referredto more generallyas geometric games [cf. Figs. 33 and 34]. They are essentially. traditionalizingand conservative: spaceless, simple, and repetitive.They are also endowed with the decorative qualitythat one associates with such forms from the fourteenthand early fifteenthcenturies and even earlier.One would have to pick at random from among the numerous instances in which similar element appears in earlier art. Shapes akin to Leonardo'swere a well-

established form that appears in decorative arts and architecture from the previous500 years in Europe, and they endured in decorative contexts well after Leonardo's time. Lunulae appear as omament on Romanesque fumiture,Gothic buildings, and they continued to flourishfor centuries as fumitureorament. One can want to see these as progressive and Renaissance in spirit, since they are linked to Leonardo's interests in mathematics and geometry (Leonardoplanned at one point a study of "continuous 141

JOSEPH MANCA

28) Anonymous, fourteenth century, bedroom murals, Florence, Palazzo Davanzati (second floor).

that quantity" would have comprised an analysis of shapes like those of the curvilateral stars), but they also closely resemble the flat decoration prevalent in Romanesque and Gothic art and architecture. Once again, Leonardo shows himself to be drawn to traditional forms that have littleto do with typical Renaissance interests or visual culture. His expressed interests in such "games" were indeed mathematicaland geometrical, as we might expect, but as with so many other aspects of his works the result is visuallypleasing and is 142

tied to traditional medieval forms. As with his notes on shading, the passages in his writings reveal only a precise, mathematical,and rathercold interest in the geometric formationof the lunulae;but the visual result is pleasing and is linked to a whole traditionin the medieval decorative arts, a transformation obsession with numof bers into prettyadomment characteristic the Gothic age and earof lier. We will see other flat, decorative, and traditional decorations in a considerationof Leonardo's knot designs.

THE GOTHICLEONARDO: TOWARDSA REASSESSMENTOF THE RENAISSANCE

Florence, Uffizi. 29) Leonardo da Vinci, <<Annunciation)>,

LEONARDO'SKNOTS First Considerations: There were several leitmotifs in Leonardo's art. Some, such as the representation varied and studied of emotional expression, three-dimensional shadowing, and the rendering of perspective, are consistent with the attitudesthat Leonardo shared with progressive artists and theorists of the fifteenthand sixteenth centuries. But Leonardo also had a Gothic side to his work; he was a transitionalartist, and many aspects of his life and art make best sense when regarded as manifestations of the late medieval mind. Among the several retrospectiveleitmotifsof his art were his knots, which appear in many forms in his artistry. Leonardo was fascinated, almost obsessed, with knots. Vasari noted the Leonardoused to '"aste his time"with the trifling task of designing ornate knots, and they appear in a series of engravings that are dedicated to his name inscribed with the name of an "Academy" [Figs. 35-38 and 40; cf. also Fig. 39]. In the 1480s, Leonardorecorded in a notebook that he owned knot designs of Donato Bramante. When he left Florence for Milan in 1482 he had in his possession some of his own designs of "manydrawingsfor knots."Throughout his career, in sheets that can be dated in a span from five decades,

Leonardo drew knots of various kinds and for numerous purposes. (These knots are most often referredto in Italianas nodi, or sometimes, as Leonardocalled them, gruppi a groppi). Knots appear in drawings by Leonardofor floor tiles [Fig. 41], sword handles, ceiling decorations, tooled leather and metal work, and in many abstract, independentstudies and doodles [Figs. 42 and 43]. Variousnodiare also embroideredalong the edges of garments of many figures in Leonardo's paintings, from the Mona Lisa to the Salvator Mundi [copy; Fig. 44] to the Cecilia Gallerani[Fig. 45]. As we have seen, knotted ropes also appear among the branches in the Sala delle Asse [Figs. 24 and 25]. The knot engravings: form and authorship: Before discussing these knots in general, it would be useful to consider certains aspects of his knot engravings, which among Leonardo's invention of this type are his most strikingand well-known.There are six of them, and they survive in a very limited number of impressions. AlbrechtDirer was attractedto these designs, and he copied the whole series, embellishing them with foliate additions;these wood engravings by the German artisthelped to make the essential knots designs known across Europe [cf. Fig. 39]. 143

JOSEPH MANCA

de' 31) Leonardo da Vinci, <<Ginevra Benci>, Washington, National Gallery of Art.

of 30) Leonardo da Vinci, <Virgin the Rocks,, Paris, Musee du Louvre.

Like the designs elsewhere in his oeuvre, the knots in not Leonardo's engravings are non-representational, intended to be vines, twigs, serpents, and so forth. The threads themselves are essentially flat, and have only the barest indicationof three-dimensionalityproduced by a black line on one side. Each of Leonardo's 144

engravings includes a main circularelement enclosing the intricate designs, and four separate comer decorations are also in knots. These main circular sections are approximately 20 centimeters across in the six engravings. Each engravingincludes a puzzlingreference in abbreviatedLatinto an "Academyof Leonardoda Vinci," a matterthat we will returnto shortly. The question of Leopardo'sauthorshipof these knots is undocumented and should not be taken for granted, although the attribution to him is usually assumed. Still, it does seem, despite any doubts that one might have, that Leonardowas responsible for the inventionof these sheets, even if he did not cut the plates himself. It similaritiesbetween the would be tedious to indicate the Morellian< elements of these engravings and Leonardo's autograph paintings and drawingsof knots. Suffice it to say that loopingends of rope in the Sala delle Asse, the thin, abstract knots on his embroideriesin paintings,and the form of knots found in his drawings stronglysuggest that Leonardodesigned the six engravings, all characterizedby similar turnings, density, and thinness of the interwovenlines. There

THE GOTHICLEONARDO: TOWARDSA REASSESSMENTOF THE RENAISSANCE

".' ''.;." .,

' ". .. . ..:. *,;

i

*-,

an ~*r,

t,-r

"'\.

^ttwTr*1"*^^*

at

I';

H

. 1 i*?,,,

-f5

-4* 1%^

-.r

i.

,'s ; -; . ,

32) Reverse of Fig. 31.

33) Leonardo da Vinci, Geometric designs (drawing), Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Codex Atlanticus, f. 44v.

is no documentaryevidence for this, but there is one sixteenth-centhe tury source, GiorgioVasari,who attributed design of the engravings to Leonardo.A look at a knotdrawninto his CodexAtlanticus by another hand will serve to illustratethe different results that can come about by an attemptto imitatehis ideas [Fig. 46]. The threads in the main part of each engravingare arrangedin a circle with elements around it divided into axes in multiplesof 6 or a There is a very wide array of designs by Leonardobased on this divisionof a circularform, from designs for water wheels and lifting devices [Fig. 47], "lunulae" "curvilateral or star"decorations [cf. Figs. 33 and 34], ecclesiastical floor plans, and even studies of shading [Fig.48]. This is not to say that the engravingsare necessarily linked to these other designs in idea, only that they stand as furtherevidence that the same person who invented the overall form of these designs also authored the knot engravings. While the inventionthat appears in the series can be ascribed to Leonardo,it is possible that the execution of the engravingsis the work of pupils or of executors of the incised plates. It could be that some assistants who fancied that they belonged to an "Academyof

Leonardoda Vinci"- which they did in the sense that, like pupilsof the philosophers of antiquity, they followed the teachings and instructionsof a master thinkerand teacher - aided in producing the engravings. Pupils or followersof Leonardocreated a rathercold bust-length image of a young woman with a similar "academic" inscription[Fig. 49]. Such assistants might, as is often the case in be collaboration, responsible for certain aspects of the productionof Leonardo's engravings, from the size of the images, to certain aspects of the modeling and design, to the choice of the type and color of the paper, and other minoraspects of the presentation,but there is littlereason to doubt that it was Leonardowho made some kind of master drawingsthat were tumed into the six engravings by collaborators. Analyses of the engravings: The engravings of gruppi have been given a broad number of interpretations concerning their for meaning and possible function. Characteristically the state of Leonardo scholarship, they are usually considered as expressing some humanistic, scientific, philosophical, or other progressive 145

JOSEPH MANCA

,: .' ..1 ,.. , --t , '..

'

r '.

- -1.rJr

I . Al1p1~

Rip

<",_ .,,

\-

--T/---T

. . ..,:..-,,*,,t';i': ."'.*p * ( *t li r-i j .n

r'' .'t n^ f,~

' !

. '

"

.

.. -

'r'

-

.

, ";.

.

.

'

*

'' ....",

I ' . :' 'f '

..i

..i '0 i .....Z;' 1

.

";a r.*!-

--:-.;

-j'J''

I I;-

.....

........ "

.n

t t*'

' d ~,:rl',~ 4

'.

.-

.ti

r

, r;~i ..?. ?:?~ltl?~~?lf~"''t''* ^, '' ;'~

a'^,

^A^

. .....

.

,

...

^

. ,

;

'

.rT

... ?

ri s

^3

r :

1;

@t - f xr

^ lv'

1.;

.-

'

* >._ ? r ,. , ' ^

*.> - r>

: ;-A f

*

_

. ..;.. ,,

A>;, '

t *

. .

' ,..'

* .

.A

(U .r : --

--I* IR"t *^ --1 * .-.r"vr4* f .-"'fff ms)nl? ....."; 4

. ..

v ' " x

!;

rmrl^': *: -fy

" ' ^ *{..l'

? ~"f -.t.*\ *

/'

A;c 'j -?~.;-.,.

*' ,

.. ...

35) Leonardo da Vinci, <<Knot,(engraving), Washington, National Gallery of Art.

r-'*

r..?

t '

'l

'r

.. ,,

.,' ,''...

34) Leonardo da Vinci, Geometric designs (drawing), Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Codex Atlanticus, f. 308v.

ideas. For example, Ananda Coormoraswamyhas argued that the six engravings of Leonardo are symbols of the universe. He stated that as they are made up of one thread each; they signifythe unity of all creation, a conceit that he traces to other cultures and diverse philosophies, citing references to knots by Homer, Plato, Dante, and many others. Similarly,Franco Berdini,basing his judgments on the notionthe knots are formedof one line that has no beginningor end, regardedthe engravings as symbols of the thread of human destiny, the chain of existence, and the cosmos itself. 146

is The problem with these interpretations that the main, central of the engravings are not formed of one line: even the larger parts designs themselves (not counting the four comer embellishments) are made up of several patterns that overlap each other. Each engraving has a differentnumber of separate, endless threads that with the others; the numbers of these threads are 6 [Fig. intertwine 35], 2 [Fig.36], 6 [Fig.37], 31 [Fig.38], 21 [Fig.39], and 18 [Fig.40]. There is apparentlyno consistent numerologicalsymbolism intended here - that is, no meaningfulstandard determiningthe number the of threads. Similarly, centraldesigns come to a differingnumber These of points or protruding turningsof the knots on the perimeter. are sometimes based on multiplesof 6 (6 or 12) and sometimes on multiplesof 8 (8, 16, and 32), but there again seems to be no basic numerological principle involved beyond Leonardo's preference for numbers. It would the division of circularforms into these particular be exciting to find some mathematical,astrological,or musicological

THE GOTHICLEONARDO: TOWARDSA REASSESSMENTOF THE RENAISSANCE

Wr V

F"VO&I

lf5xi

,a4%-6o

36) Leonardo da Vinci, <Knot, (engraving), Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana.

37) Leonardo da Vinci, c<Knot, (engraving), London, British Museum.

symbolism here, but no such intentionsappear to be at work. One must conclude that the appeal of the engravings must be sought in their visual qualities. At any rate, the knots surely are not formed of single lines, and therefore do not connote or suggest the eternityof a divinely unending thread. It is temptingindeed to find a cosmic significancein knot decorations,but whether in the works of Leonardoor others, it often tums out that the basis is lackingfor such an interpretation. The knotting patternin Raphael's altarin the Disputa could reasonably be thought of as allusive to eternity,order, and earthly harmony,since the altar links Heaven with the simple geometry of earthlyexistence. But the

motif appears frequently in Raphael's paintings,as it does in the works of other Umbrianartists of the time, includingthose of his teacher, Perugino. Similarly, in Mantegna's Madonna of Victory (Pars, Louvre)a knot design hovers over the Virgin's head as if, it would seem, it were some kind of celestial symbol. Yet Mantegna also used similarknot patterns on the car of Julius Caesar in the Hampton Court Triumphsof Caesar, on the orientalcarpet in his Introduction of the Cult of Cybele to Rome (London, National Gallery),and on the fictive cloth hangings in the Camera Picta in Mantua. Similarly,knots appear in Leonardo'soeuvre in many different contexts, and any theory that attempts to give too specific an 147

JOSEPH MANCA

i"

~-

~

-..W~,

WI iA

'

38) Leonardo da Vinci, (<Knot,> (engraving), Washington, National Gallery of Art.

explanation for them all will inevitably miss the mark in some respect, since the contexts are differentfor each applicationof the design. Nor is there any writtenevidence on his part to suggest that the engravings or any of his other gruppi designs have any lofty iconographic significance. On a differentlevel, some have given practicalexplanations of the actual use of Leonardo'sengravings. They have been thoughtto be entrance tickets to philosophical disputations, or as prizes for on winningsuch a debate, as the reference to an "academy" some of them seems to allude to the existence of an intellectual institution that might have sponsored such an event. It has even been suggested that the discussions were held in the Sala delle Asse, where similarknots appear as ropes in the painted decoration[cf. Figs. 24 and 25]. But there is no evidence that there was any formal,regular "Academyof Leonardo da Vinci."It is most probable,as Hind and others argued long ago, that there was, at most, an informal gathering of artists near to Leonardowho perhaps met from time to time and who liked to imagine that they constitutedan academy. Nor it is 148

(woodcut), 39) Albrecht Durer, after Leonardo da Vinci, <<Knot,, Washington, National Gallery of Art.

likelythat these engravings, bulky as they are for such a purpose, would have been useful as entrance tickets of any sort. More likely is the notion that these engravings were meant to serve as models for the decorationof books, since there are numerous book-coverings from the Quattrocentothat are decorated with knots of one type or another,often with a main section adomed with four separate comer knots. This is not a stylisticobservation,but it is one that throws a plausible light on their function.Still, the question of why Leonardowas interested in this form of decorationover another remains unanswered; nor does the explanation account for the numerousother knots that appear in his oeuvre. In any case, the connection of Leonardowith books and printing seems to be forcing a kind of literaryor humanisticexplanationof the knots. After all, there are no known early bookcovers that are based on Leonardo's

THE GOTHICLEONARDO: TOWARDSA REASSESSMENTOF THE RENAISSANCE

(%pl

41) Leonardo da Vinci, <Design for a Floor Tile)>(drawing), Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Codex Atlanticus, f. 701 r.

40) Leonardo da Vinci, <(Knot>(engraving), Washington, National Gallery of Art.

knot engravings, and no documented evidence or indication that any have ever been made. The knot engravings have also been thought to refer to the = artist's own name, the "vincoli" (knots or fetters; "vincire" to fetter or knot) acting like a signature and personal emblem. Again, this suggests that the design communicates a progressive and typically Renaissance idea, namely, an aggrandizingand proudexpression of the Self that combines the creator's identitywith the artworkitself. Yet knots frequentlyappear in the works of other artists, even those not fromVinci, and this theory thus unnecessarily isolates Leonardo. Nor does it consider the varietyof the nodi within Leonardo's own oeuvre, or the style and aesthetic qualities of his knot drawings or engravings. The notion of the knots as signatures cannot be refuted, and it could well contain some truth,but it is rathernarrow,occupy-

ing only a part of the overdeterminate response that would account for the broader picture. Particularly,this explanation does not attempt to account for the origins of the obvious aesthetic delight that Leonardotook in designing such forms, and why they appear so often as doodles in his notebooks, where any idea of a publicsignature would be unnecessary. It has been pointed out that medieval artists sometimes signed their names in labyrinthine decorations. Several architects of Gothic cathedrals used such devices, thought to have symbolized the of labyrinth Daedalus. It would be easy to exploit this apparentsimilarityin a study of a Gothic Leonardo,but the argument is unconvincing.At any rate, despite the medieval context of this practice,the connection of this usage with Leonardoagain could arguablyconstitute a progressive idea: that he was identifying himself as a creator, that he was insistenton "signing" works, and that he was like the his classical Daedalus in his labyrinthine inventiveness. Yet, it is important to emphasize that no knots by Leonardoform actual labyrinths. Moreover, only his engravings - with their roundedform and "signatures" in the middle - are even superfically close to Gothic 149

JOSEPH MANCA

f?j1

?

, .. .,: ., :^ ,.- ~ ? !'~-,.',..,,.,;.,.;.?., .. ~; ? W "?... ^^.^'*^"^A ..

~~~~

?"""

:p? '. ' ), ; 1r? ??I" Y.. "r;

L

. .*. .

. ?.,

a..

"

6'E;? ??; - "t??

.I.? .;Lf:r?.

I?-?ii t'?

...: .,

t?t

.? .Y !,?ai:

t ;?.r "?I. ;'?';?q;*: I

? .I i,' :;i r--?;,.t? .??-Y (? 61' :jl r': L?.;;,::X:i'ri? ?c ."?: J? Ice? ;:* I"."'i' .r? L?tt;v? ?.,..: :C c . rJ ,... Yfi?l ?

: ? ?:';: .IIh.? ':.i =-

'1 !r ?'?.I r?? c; i:422L 1.z .??? ?I IL1???u*? ii*?rct *F Fji .t?i. Sf'i ?.;

2'7

I

.

..-??n

ic?a

-

?;?-- f?': kL??

*T :'C

5

r .

*^^%^.T 1. ,

;sw ,.- .

* r*'* ~ .^' ''^^

'

i"'?-

?, r 'cr?

'* '*' - - 1 fJ '?;'^_

_ '

*,

.e ?-

.*

rq

":

i..A

..

?.f?

..-.

fl

::

t?s

;.

.ll-

K.-

:.,- -. l-,

"

"..,..

'

. ? 'M,

...t'.

o'

'

...p" .. . . -1N,. . .

...

" .:

-I.3

* ^ t ,,

-:.

It;'i rg ?'*P

i ?? :?

lb.

; ' wi '

t?.? , It . a?:,-~s

42) Leonardo da Vinci, (<KnotDesigns) (drawing), Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Codex Atlanticus, f. 190v.

Designs, (drawing), Milan, 43) Leonardo da Vinci, <<Knot Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Codex Atlanticus, f. 1066r.

labyrinth signatures (for example, his garment border designs have a very differentvisual effect). The knots of Leonardodo knot form mazes, and the connection with Daedalus is off the mark. One could argue that knots of the later Quattrocento,including Leonardo's, were made in imitatione antiquitatis, inspired by white vine motifs, believed in the Renaissance to reflectan ancient Roman motif. But knots appear in the arts of many different periods and countries, and Leonardosurely knew Westem medieval and Islamic knots, just as he was aware of knottedcovers for humanisticbooks. Knots had a long history before Leonardo, appearing in numerous forms, including Hiberno-Saxon manuscripts, Islamic decorations, and Carolingian and Romanesque manuscript illuminations.Most 150

motifs so favored for supposed all'antiimportantly,the intertwining ca manuscriptsin the Quattrocento were, as J.J.G. Alexander put it, norther and medieval ratherthan trulyclassical. Indeed, by the sixteenth century it became clear that elaborate and intricate knots were not a genuine part of classical decoration,and the motif went into disuse as an all'anticaelement. To be sure, it is of great interest that this white vine traditionwas thought to be based on classical illuminators, ideas, but it is also telling that these fifteenth-century and Leonardo,too, were actually imitatingmedieval decorations. It is significantthat Quattrocentoartists thought that the white vine motif was a classical one, but more telling still is that they engaged in a practice that was medieval. The question of the con-

THE GOTHICLEONARDO: TOWARDSA REASSESSMENTOF THE RENAISSANCE

Mundi>, Paris, 44) Copy after Leonardo da Vinci, <<Salvator private collection.

with an Ermine [Cecilia 45) Leonardo da Vinci, <<Lady Gallerani],,, Cracow, Fundacja Ksiqzqt Czartoryskich.

tinuationof decorative motifs from the MiddleAges throughthe Early Renaissance indicates that there was a continuity taste from one of period to the other. Leonardo shared in this continuingtradition,as did many of his contemporaries. is, in any study of Leonardo,highIt that knots appear in the art of Verrocchioand his circle, ly significant and a delight in the intertwining ropes appears in Verrocchio's of sculptureas well, in the tomb of Giovanniand Piero de' Mediciin the Old Sacristy. Leonardo surely received from Verrocchio an early interst in elegant, interlacingdesign. Elsewhere in Italy,the idea of knots circulatedmost widely among painters who retained some lingering Gothic elegance in their works, including Verrocchio,

Leonardo, Pinturicchio, and Raphael. Even the rather inelegant Mantegnawas drawn to knots, suggesting that the survivalof a traditional,linear patter was widespread indeed in the fifteenthcentury. h Andrea's art, the energizing linearityof knot pattems correand sponds to some (if not all) aspects of his liney design mentality, serves as a reminderthat the linearity Quattrocento of paintingis not unrelated to the rhythmiccontours and flowing design of medieval art. This attraction to linear design greatly lessened during the Cinquecento, replaced by a compositionalapproach based more on mass and form than on lively line. Again, as in so many other aspects of his style, Leonardo stood at the center of this time of 151

M^

JOSEPH MANCA

,?

,,~,-.'.^.,^,/.'>', *."'-.. .,'t.:,, .',

oP".?*tt'iSt"1.;.,, >? .1

_ b _'"|;., A P _*- t

.

,

; * , .'^ "

...

e'.

/

.....

.............

. .

v.,

,t

,

-'--

.'.. ... . a..

' W. ''

:'" . .

. v... .

*.. .

'J...:

,,;, .

*

./.:.

_. :i"t? ''? *. ,

~*?rl.r * ,,.:.-*.. *.;, .. '??;""-"~w : .,.. ....I~ /~~~~~~~~.

..A ............: i.......

trze b ' '. '-...,.., E tRw, 'ANA t4W? :}

t -:;

._

---

I . '*% ~~~~~~~~~i,

?. ,.: .- , .

...

\;.'.,x,

I'T I ?' -?: ' I ?,

i .f.

4'

9

?, . . ., I

b,-!- ,.

y.. -

i :"",,~

'

.. ...

'

"r :?

A I. .p.

*

1

i?

a, \

,,

b~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

:d

r

.. .... ?i * . , *I . . ,* ; .,.

* 3i)?~

*t.

r.

.'.

:'" ? ', 4

*V\~(7

*((

47) Leonardo da Vinci, ((Designs for Water Wheels), (drawing), Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Codex Atlanticus, f. 1062r.

/:t

*, ;:,-i 'A : i~

:,..?. , ?, * " ....

?U

E? ....I?? 'L 1* :;" li: u :? ..!.,... ?ix::? :" ? ?".:nr?liic;ijZ.pA:i !':'!iii::3? .: ???J.

;a

~ ~ :I~~~~~~8:

"

.'..'z "~:;:' " A, . . . . . :. ' i ,,: : '.x:

l;

.... i

o

* "k.i.:t t

2??. 'i

'

::.a?tliat!:IPfX:

iiR

e b

*' g ii.. *cl?...rpl "'"?:i:t

*... ..........:,

*:_.,,A..::., .;., .F.;,:,..

. .

,,:?. .. ~1

{.;,];

, i.:~,.,,..,-&

.. ': ,,?