Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The Language Crusade

Încărcat de

Sonny NeuDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Language Crusade

Încărcat de

Sonny NeuDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Top of Form

delivery

a7fa682b-81eb-4

H4sIAAAAAAAE

Back 1 article(s) will be saved. To continue, in Internet Explorer, select FILE then SAVE AS from your browser's toolbar above. Be sure to save as a plain text file (.txt) or a 'Web Page, HTML only' file (.html). In Netscape, select FILE then SAVE AS from your browser's toolbar above.

EBSCO Publishing

Citation Format: APA (American Psychological Assoc.):

NOTE: Review the instructions at http://support.ebsco.com/help/?int=ehost&lang=&feature_id=APA and make any necessary corrections before using. Pay special attention to personal names, capitalization, and dates. Always consult your library resources for the exact formatting and punctuation guidelines.

References Torres, J. (1996). The language crusade.Hispanic, 9(6), 50.Retrieved from EBSCOhost. <!--Additional Information: Persistent link to this record (Permalink): http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=f5h&AN=9606250963&site=ehost-live End of citation-->

THE LANGUAGE CRUSADE What's really behind the campaign for "Official English"? The great Chicano artist, poet, and writer Jose Antonio Bur-ciaga once wrote about a dream he had in which English was declared the nation's official language. The names of familiar towns, cities and famous landmarks were changed to their English translations. Puerto Rico became "Rich Port." Rio Piedras and Isla Caja de Muertos were called "Rock River" "Dead Man's Casket Island." Alamo became

"The Poplar" El Paso changed to "The Pass," Boca Raton was called "Rat's Mouth," and Yerba Buena became "Good Weed." Opponents of "Official English" have fun with Burciaga's translations, but clearly this issue of language isn't funny. There was little humor in the Supreme Court's recent decision to review an Arizona case, Yniquez v. Arizonans for Official English this fall. In the case, a state Official English amendment passed in 1988 was found unconstitutional by a lower court. Presidential candidate and Senate majority leader Bob Dole (R-Kansas) wasn't laughing when he endorsed Official English while addressing the American Legion convention in Indianapolis last September. Dole said, "English should be acknowledged once and for all as the official language of the United States." Dole's presidential bid and the upcoming Supreme Court review of the Yniquez case have moved the debate over language into uncharted territories. Official English critics have consistently labeled the attempt to legislate language as ridiculous. They call the language debate a non-issue. They point to the 1990 U.S. Census, which reports that 97 percent of all U.S. residents speak English. They admit, however, that these are dangerous times. The election of the Republican-con- trolled 104th Congress in 1994 has brought unprecedented support for Official English legislation, and Official English hearings have been held in both houses of Congress. "This year represents the greatest risk that an Official English bill will pass out of Congress," said Ed Chen, staff attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union in San Francisco. Four major Official English bills were introduced in the first session of the 104th Congress last year. Bills have been sponsored by Senator Richard Shelby (R-Alabama) and Representative Bill Emerson (RMissouri) which call for making English the "official language" of government. Two bills sponsored in the House by Representatives by Peter King (R-New York) and Toby Roth (R-Wisconsin) go even further by calling for the elimination of bilingual education and bilingual ballots. Representative John Doolittle (R-California) also introduced an amendment which, if adopted, would amend the Constitution to declare English the official language of government of the United States. Analyzing the increased momentum of this issue, Representative Esteban Torres (D-California) said that Official English is growing because of the polit- ical tenor that is predominant in the country. "This has become avery good tool to advocate against anybody who speaks a language other than English . . . and also conveys the concept of who really belongs here." The debate has been brewing ever since former Senator S.I. Hayakawa (R-California) introduced an Official English constitutional amendment in 1981. At the time, the amendment found few supporters. In 1983 Hayakawa founded the Washington-based group U.S. English (a "national, nonpartisan,

nonprofit citizen's action group") after retiring from the Senate. The organization, whose current chairman is Chile-born Mauro E. Mujica, bas been instrumental in spearheading passage of officialEnglish legislation through several state houses. Currently, 23 states have Official English laws on the book and at least 10 others, including California and Georgia, have legislation pending. Despite a General Accounting Office report released last year that said 99.94 percent of all federal government documents are produced in English, Official English proponents argue that more than 300 languages are spoken in the United States, and for the sake of cost-effectiveness and unity, the government needs to legislate and conduct its business in English. They also regularly stress that the overwhelming majority of U.S. citizens favors making English the official national language. A poll conducted by U.S. News and World Report last September showed that 73 percent of U.S. voters favored making English the official language of government. Last August, U.S. English conducted its own poll, which asked 1,208 U.S. citizens the question: "Do you think English should be made the official language of the United States?" The poll revealed that 86 percent of all U.S. citizens and 81 percent of first-generation immigrants answered yes. Some dispute the accuracy of such polls. Karen Hansen, an education policy analyst for the National Council of La Raza, said too often, polls are designed to elicit a specific response by not providing their respondents with enough information. While on speaking engagements, she often asks groups what percentage of the U.S. population speaks English. Typically, responses range from 50 to 75 percent. "They are shocked when they learn it's 97 percent," she said. In 1986 the Virginia-based group English First was founded by Larry Pratt, who also started Gun Owners of America. (Pratt may best be remembered for having to step down earlier this year as cochairman of GOP presidential candidate Patrick Buchanan's campaign for allegedly making public appearances with leaders of white supremacist organizations, including the Aryan Nation and Christian Identity.) Buchanan has also endorsed Official English. With little demonstrated need to support Official English, opponents of the movement have labeled it xenophobic and racist. Chen says that Official English supporters play on the fears that many nonHispanic white U.S. citizens have of the "browning of America." According to the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, in the fifties, 53 percent of all legal immigrants in the United States were from Europe, with 22 percent from Latin America. Conversely, in the eighties, only 10 percent were from Europe and 47 percent were from Latin America. The U.S. Hispanic population has increased from 9 million in 1970 to 27 million in 1995, and the U.S. Census Bureau has projected that by 2050 the mainland U.S. Hispanic population will reach 88 million, 20 percent of the total population. Census figures reveal that in 1990, 32 million U.S. residents five years of age and older spoke a language

other than English at home. More than 54 percent spoke Spanish. The majority, however, also spoke English "well" or "very well." Jim Lyons, executive director of the National Association for Bilingual Education, criticizes U.S. English and English First for supporting bills over the years that do not increase the availability of programs that teach English. In New York, English as a Second Language (ESL) classes have waiting lists ranging from six to eighteen months, and in Los Angeles. ESL programs have waiting lists of 20,000 to 40,000 people. Jim Crawford, a Maryland-based author who has written several books on the language debate, including Hold Your Tongue: Bilingualism and Politics of English Only, said immigrants are learning English faster than previous generations because there are greater economic incentives to do so. In his writings, Crawford documented the origins of the Official English movement. In its beginning form, it was a movement to curb immigration and then evolved into focusing on language. "It is absurd that English needs legal protection," said Crawford. "If you look at the facts--that immigrants are learning English--and then look at what's underneath the English-Only campaign, you will find that it's prejudice toward immigrants and fear that the nation is losing its cultural and racial identity." Indeed, literature from Official English groups and comments from its defenders appear to support Crawford's point that racism is the motivating factor. A 1995 membership solicitation letter from U.S. English chairman Mujica sensationalized the issue and attempted to push the emotionally charged nationalism button. It began with a reference to the Arizona case being reviewed by the Supreme Court. It read, "Do you know Armando Ruiz? How about John Philip Evans or Rosie Garcia? Candido Mercado? James Padilla? Manuel Pena, Jr.? Peter Rios? Evangelina Rivas? MacarioSaldate IV? Federico Sanchez? Victor Soltero? Let me give you clues: 1. They all live in Arizona 2. They're all on the government payroll 3. And, together they've filed a lawsuit that could change your life forever." In 1988 U.S. English co-founder John Tanton resigned as chairman of U.S. English after a 1986 memo he wrote was disclosed. In it, he asked, "In this society, will the present majority peaceably hand over its political power to a group that is simply more fertile? . . . As whites see their power and control over their lives declining, will they simply go quietly into the night? Or will there be an explosion . . . We are building in a deadly disunity." The memo led to the resignation of its president, former Ronald Reagan appointee Linda Chavez, and advisory board member Walter Cronkite. An early fund-raising letter from English First stated, "Tragically, many immigrants these days refuse to learn English! They never become productive members of society. They remain stuck in a linguistic and economic ghetto, many living off welfare and costing working Americans millions of tax dollars

every year. Radical activists have been caught sneaking illegal aliens to the polls and using bilingual ballots to cast fraudulent votes. . . ." Jim Boulet, Jr., executive director of English First, has defended the group and its founder. When asked why legislation is needed for Official English when 97 percent of U.S. citizens speak English, he answered, "Most people in the country don't think murder is a good idea, but we have laws against it." Hispanic organizations have protested that discrimination against Hispanics and non-English speakers is on the rise because of the Official English movement. Last year a Texas district court judge ruled that a Latina mother was abusing her daughter by speaking only Spanish to her. He ordered the mother to speak English to her daughter to ensure "she's not relegating her to a position of a housemaid." Andy Banks, an international representative with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, said that businesses are using the issue to exploit workers. In Miami, the Teamsters have helped employees of Fritz's Stair Cargo, a freight forwarding and logistics company, to file a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission accusing the company of forcing workers to accept a threetiered wage system that links an employee's salary with his or her ability to speak English. Banks said the company allegedly pays Spanish-speaking employees less than its English-speak-ing workers. Fritz's Stair Cargo has denied the charges. Anticipating increased charges of discrimination in the workplace, the ACLU has initiated a hot-line so that employees all over the country can report when they have been discriminated against due to language restrictions. The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) began a national hot-line last year to register complaints against employerswhoprohibit Latino employees from speaking Spanish in the work place. MALDEF's hot-line received more than 88 calls in the first 48 hours it was up and running. The ACLU, according to Chen, ran local television public-service announcements in northern California about its language discrimination phone line earlier this year. The San Francisco office received 40 phone calls the week the spot ran. It normally averages 10 such calls per week. Opponents of U.S. English and English First, such as the ACLU and MALDEF, have difficulty defusing the special interest groups' messages despite the tainted backgrounds of the organizations, their propaganda, and an increasing number of reported discrimination cases. The U.S. English and English First rely on catchy sound bites when describing programs they oppose. Bilingual education, for example, is called "linguistic welfare" in a brochure. Representative Roth, who testified at a December hearing on Shelby's Official English bill said, "I want to keep America one nation, one people. We must preserve the common bond that has kept this country of immigrants together for more than two centuries by making English our official language."

According to Chen, people respond to the Official English message because it is "simplistic" and "it seems like the fight thing to do. It is a message that sounds non-racist and nice, which is why it's hard to fight. Our response is not a catchy one-line answer, but an explanation." When asked whether Hispanics support Official English, NABE's Lyons barked, "I don't know a Latino organization in the country that supports it." Most Latino organizations may agree on the issue, but not all Latinos do. Besides figureheads like Mujica and Chavez, some Hispanics do have conflicting views on the subject. Depending on the generation, some Mexican American parents encouraged immersion in English to protect their children from the ridicule they endured as Spanish speakers entering American schools. Other Hispanics believe English proficiency is a key factor for success in the U.S., while others, who understand the dominance English maintains in this country, simply consider the issue redundant. With both the Democratic and Republican national conventions approaching in August, the political waters will get rougher as Dole and Clinton will each attempt to define each other and their candidacy with issues that appeal to the voters, or the lowest common denominator. The hot-button nature of the language issue means that it has the potential to ignite nationalist fervor in non-Hispanic America even more than it already has. Perhaps as the campaign drags on, a candidate who exposes the issue's true racist basis will emerge. Or maybe an observer like Burciaga would help by providing us with another of those Official English dreams that put the debate in its proper perspective. ILLUSTRATIONS ~~~~~~~~ By JOSEPH TORRES

Copyright of Hispanic is the property of ET Publishing International and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Back

enabled

Bottom of Form

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- English Only Legislation Literature Review SummaryDocument5 paginiEnglish Only Legislation Literature Review Summarymanolo_santiago_3Încă nu există evaluări

- Wolfe Carla Essay 1 English Only Yes or NoDocument6 paginiWolfe Carla Essay 1 English Only Yes or NoCarla WolfeÎncă nu există evaluări

- English As An Official Language 3Document20 paginiEnglish As An Official Language 3Jorge del Toro CabreraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rough DraftDocument8 paginiRough Draftapi-217222073Încă nu există evaluări

- An American Language: The History of Spanish in the United StatesDe la EverandAn American Language: The History of Spanish in the United StatesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical AnalysisDocument5 paginiCritical AnalysisMike D'Errico a.k.a. The Attic Bat100% (1)

- Transforming Politics, Transforming America: The Political and Civic Incorporation of Immigrants in the United StatesDe la EverandTransforming Politics, Transforming America: The Political and Civic Incorporation of Immigrants in the United StatesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Huddled Masses Myth: Immigration And Civil RightsDe la EverandThe Huddled Masses Myth: Immigration And Civil RightsÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1-One Peopleone LanguageDocument5 pagini1-One Peopleone LanguageGiuliana ArcidiaconoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Immigration and Language Rights - The Evolution of Private Racist PDFDocument38 paginiImmigration and Language Rights - The Evolution of Private Racist PDFJuan Antonio Aguilar JuradoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emergence of One American Nation: The Revolution, the Founders, and the ConstitutionDe la EverandThe Emergence of One American Nation: The Revolution, the Founders, and the ConstitutionÎncă nu există evaluări

- About The Languages of The United StatesDocument3 paginiAbout The Languages of The United StatesJbingfa Jbingfa XÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation, Second EditionDe la EverandThe Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation, Second EditionEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Feagin and Cobas Language Oppression and Resistance The Case of Middle Class Latinos in The UDocument22 paginiFeagin and Cobas Language Oppression and Resistance The Case of Middle Class Latinos in The UOscar Fluxus DiazÎncă nu există evaluări

- La Constitución de Los Estados Unidos en Español: Un Servicio para El Pueblo AmericanoDocument26 paginiLa Constitución de Los Estados Unidos en Español: Un Servicio para El Pueblo Americanomariae2Încă nu există evaluări

- State of White America 2007Document108 paginiState of White America 2007Jack and friend100% (1)

- Spanish435 Spring2017 Dottypaper Draft2Document6 paginiSpanish435 Spring2017 Dottypaper Draft2api-370831926Încă nu există evaluări

- Rallying for Immigrant Rights: The Fight for Inclusion in 21st Century AmericaDe la EverandRallying for Immigrant Rights: The Fight for Inclusion in 21st Century AmericaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Language PolicyDocument5 paginiLanguage PolicyMiguela LabiosÎncă nu există evaluări

- HW Article Gqs - Language Divide in AmericaDocument6 paginiHW Article Gqs - Language Divide in Americaapi-281321560Încă nu există evaluări

- Views On BilingualismDocument22 paginiViews On BilingualismaspiredÎncă nu există evaluări

- Race and the Obama Phenomenon: The Vision of a More Perfect Multiracial UnionDe la EverandRace and the Obama Phenomenon: The Vision of a More Perfect Multiracial UnionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Immigrant Neighbors among Us: Immigration across Theological TraditionsDe la EverandImmigrant Neighbors among Us: Immigration across Theological TraditionsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Miscellany 15: Was America Destroyed by the Jews?De la EverandMiscellany 15: Was America Destroyed by the Jews?Încă nu există evaluări

- Gale Researcher Guide for: The Continuing Significance of Race and Ethnicity in the United StatesDe la EverandGale Researcher Guide for: The Continuing Significance of Race and Ethnicity in the United StatesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Black Image in the White Mind: Media and Race in AmericaDe la EverandThe Black Image in the White Mind: Media and Race in AmericaÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Are The Most Spoken Languages in The U.S.Document3 paginiWhat Are The Most Spoken Languages in The U.S.lorenzo mahecha villaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Searching for Subversives: The Story of Italian Internment in Wartime AmericaDe la EverandSearching for Subversives: The Story of Italian Internment in Wartime AmericaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Task English OnlyDocument2 paginiTask English OnlyVassiliki Amanatidou-KorakaÎncă nu există evaluări

- SPLC Report Examines Extremist Views of Lawmakers Attacking 14th AmendmentDocument22 paginiSPLC Report Examines Extremist Views of Lawmakers Attacking 14th AmendmentFiredUpMissouriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Israel and the Struggle over the International Laws of WarDe la EverandIsrael and the Struggle over the International Laws of WarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week3 Spolsky2011Document6 paginiWeek3 Spolsky2011api-271886173Încă nu există evaluări

- Manifest Destinies, Second Edition: The Making of the Mexican American RaceDe la EverandManifest Destinies, Second Edition: The Making of the Mexican American RaceEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (6)

- Minority Relations: Intergroup Conflict and CooperationDe la EverandMinority Relations: Intergroup Conflict and CooperationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unwanted: Italian and Jewish Mobilization against Restrictive Immigration Laws, 1882–1965De la EverandUnwanted: Italian and Jewish Mobilization against Restrictive Immigration Laws, 1882–1965Încă nu există evaluări

- Language Arts: Sound smarter without trying harderDe la EverandLanguage Arts: Sound smarter without trying harderEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (1)

- The Preacher and the Politician: Jeremiah Wright, Barack Obama, and Race in AmericaDe la EverandThe Preacher and the Politician: Jeremiah Wright, Barack Obama, and Race in AmericaÎncă nu există evaluări

- White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide by Carol Anderson | Conversation StartersDe la EverandWhite Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide by Carol Anderson | Conversation StartersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning to Speak a New Tongue: Imagining a Way that Holds People Together—An Asian American ConversationDe la EverandLearning to Speak a New Tongue: Imagining a Way that Holds People Together—An Asian American ConversationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bilingualism Part IIDocument3 paginiBilingualism Part IIRoxanne CaruanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Voice of the Foreign Service: A History of the American Foreign Service AssociationDe la EverandThe Voice of the Foreign Service: A History of the American Foreign Service AssociationÎncă nu există evaluări

- America in Black and White: One Nation, IndivisibleDe la EverandAmerica in Black and White: One Nation, IndivisibleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crawford, James. Hold Your TongueDocument46 paginiCrawford, James. Hold Your TongueanacfeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thomas F. Magner: The Pennsylvania State UniversityDocument11 paginiThomas F. Magner: The Pennsylvania State Universitygoran trajkovskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reclaiming America: Nike, Clean Air, and the New National ActivismDe la EverandReclaiming America: Nike, Clean Air, and the New National ActivismEvaluare: 3 din 5 stele3/5 (1)

- A Government by the People: Direct Democracy in America, 1890-1940De la EverandA Government by the People: Direct Democracy in America, 1890-1940Încă nu există evaluări

- America's Race Matters: Returning the Gifts of Race and ColorDe la EverandAmerica's Race Matters: Returning the Gifts of Race and ColorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Latinos in America: Philosophy and Social IdentityDe la EverandLatinos in America: Philosophy and Social IdentityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diversity's Child: People of Color and the Politics of IdentityDe la EverandDiversity's Child: People of Color and the Politics of IdentityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thank You for Voting Young Readers' Edition: The Past, Present, and Future of VotingDe la EverandThank You for Voting Young Readers' Edition: The Past, Present, and Future of VotingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presente!: Latin@ Immigrant Voices in the Struggle for Racial Justice / Voces Inmigranted Latin@s en la Lucha por la Justicia RacialDe la EverandPresente!: Latin@ Immigrant Voices in the Struggle for Racial Justice / Voces Inmigranted Latin@s en la Lucha por la Justicia RacialÎncă nu există evaluări

- Racial Formations and Discrimination Laws in US HistoryDocument2 paginiRacial Formations and Discrimination Laws in US HistoryAlastair HarrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- English History and Its Importance - Short EssayDocument5 paginiEnglish History and Its Importance - Short EssayKarenn PalomoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1996 GMC Jimmy OwnersDocument390 pagini1996 GMC Jimmy OwnersSonny Neu100% (1)

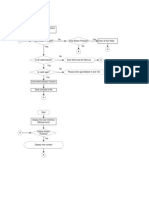

- PRG421 Week 2 - FlowchartDocument1 paginăPRG421 Week 2 - FlowchartSonny NeuÎncă nu există evaluări

- PRG421 Discussion Question # 1 - Arrays and Combo BoxesDocument2 paginiPRG421 Discussion Question # 1 - Arrays and Combo BoxesSonny NeuÎncă nu există evaluări

- PRG421 Week 3 - FlowchartDocument1 paginăPRG421 Week 3 - FlowchartSonny NeuÎncă nu există evaluări

- PRG421 Discussion Question # 2 - MenusDocument3 paginiPRG421 Discussion Question # 2 - MenusSonny NeuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Characteristics of Oriental Ism, Prejudice, and DiscriminationDocument2 paginiCharacteristics of Oriental Ism, Prejudice, and DiscriminationSonny NeuÎncă nu există evaluări

- PRG421 Discussion Question # 2 - Writing Code For A Data FileDocument1 paginăPRG421 Discussion Question # 2 - Writing Code For A Data FileSonny NeuÎncă nu există evaluări

- PRG421 Discussion Question # 1 - Exception HandlerDocument1 paginăPRG421 Discussion Question # 1 - Exception HandlerSonny NeuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Delegate Carroll Foy Bail Reform LetterDocument2 paginiDelegate Carroll Foy Bail Reform LetterLowell FeldÎncă nu există evaluări

- UPSC Mains Worksheets: Indian PolityDocument10 paginiUPSC Mains Worksheets: Indian PolityAditya Kumar SingareÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pangilinan v. CayetanoDocument16 paginiPangilinan v. CayetanoSharen Ilyich EstocapioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Schedule G Ownership DetailsDocument2 paginiSchedule G Ownership DetailsMoose112Încă nu există evaluări

- Competition Project - CartelsDocument18 paginiCompetition Project - CartelsalviraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ubi Jus Ibi RemediumDocument9 paginiUbi Jus Ibi RemediumUtkarsh JaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7.MSBTE Examination Procedures of Examination Cell and COEDocument5 pagini7.MSBTE Examination Procedures of Examination Cell and COEpatil_raaj7234100% (1)

- Irr Ra 11917Document92 paginiIrr Ra 11917Virgilio B AberteÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Alexandra Condominium Corporation VsDocument3 paginiThe Alexandra Condominium Corporation VsPinky De Castro AbarquezÎncă nu există evaluări

- CAREC Corridor 1 Procurement PlanDocument5 paginiCAREC Corridor 1 Procurement Planabuelazm2132100% (1)

- DepEd Isabela City updates on PAAC issues from Jan-Sept 2020Document2 paginiDepEd Isabela City updates on PAAC issues from Jan-Sept 2020Az-Zubayr SalisaÎncă nu există evaluări

- PFR-Franklin Baker Vs AlillanaDocument5 paginiPFR-Franklin Baker Vs Alillanabam112190Încă nu există evaluări

- Lim v. People, GR No. 211977, October 12, 2016Document13 paginiLim v. People, GR No. 211977, October 12, 2016Charmila SiplonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legal English Inheritance Law Property Law (Mgr. Kołakowska)Document2 paginiLegal English Inheritance Law Property Law (Mgr. Kołakowska)KonradAdamiakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consitution - Meaning, Need, TypesDocument20 paginiConsitution - Meaning, Need, TypesJoseph MondomaÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States v. Franco Anthony Smith, 166 F.3d 1223, 10th Cir. (1999)Document3 paginiUnited States v. Franco Anthony Smith, 166 F.3d 1223, 10th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sworn Statement of Accountability of The PreparersDocument2 paginiSworn Statement of Accountability of The PreparersLugid YuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 3 Case DigestDocument7 paginiChapter 3 Case DigestAudreyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1-33504247894 G0057436708 PDFDocument3 pagini1-33504247894 G0057436708 PDFAziz MalikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Government of The Virgin Islands v. Eurie Joseph, 964 F.2d 1380, 3rd Cir. (1992)Document18 paginiGovernment of The Virgin Islands v. Eurie Joseph, 964 F.2d 1380, 3rd Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- CIR v. Mirant PagbilaoDocument4 paginiCIR v. Mirant Pagbilaoamareia yap100% (1)

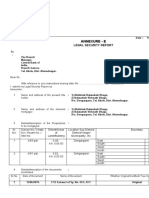

- Annexure - E: Legal Security ReportDocument7 paginiAnnexure - E: Legal Security Reportadv Balasaheb vaidyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- College History AnalysisDocument2 paginiCollege History AnalysisYayen Elivaran Castor100% (1)

- Antonio Lejano Case DigestDocument5 paginiAntonio Lejano Case DigestMcÎncă nu există evaluări

- Personnel Action FormDocument1 paginăPersonnel Action Formsheila yutucÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1601 CDocument6 pagini1601 CJose Venturina Villacorta100% (1)

- Bill of Rights Sec 1Document295 paginiBill of Rights Sec 1Anabelle Talao-UrbanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Camarines Sur election results by cityDocument2 paginiCamarines Sur election results by cityRey PerezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sandoval V HretDocument5 paginiSandoval V HretSarah Jane UsopÎncă nu există evaluări

- Court of Appeals Abuses Discretion in Dismissing PetitionDocument5 paginiCourt of Appeals Abuses Discretion in Dismissing PetitionPHI LAMBDA PHI EXCLUSIVE LAW FRATERNITY & SORORITYÎncă nu există evaluări