Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Orthodontic Treatment of Localised Gingival Recession - Aust - Orthod.j

Încărcat de

kadrologyDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Orthodontic Treatment of Localised Gingival Recession - Aust - Orthod.j

Încărcat de

kadrologyDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Orthodontic treatment of localised gingival recession associated with traumatic anterior crossbite

Jadbinder Seehra, * Padhraig S. Fleming and Andrew T. DiBiase *

Maxillofacial Unit, Kent and Canterbury Hospital,* and the Royal London Dental School, United Kingdom

Background: Gingival recession can be defined as the apical shift of the marginal gingiva from its normal position on the crown of the tooth to levels on the root surface beyond the cemento-enamel junction. The aetiology of this condition is multifactorial, but can result from a traumatic occlusion. The long-term prognosis of teeth with localised gingival recession can be uncertain. Successful management of these cases may involve either orthodontic or periodontal treatment in isolation or in combination. Aim: To describe two patients in which localised gingival recession associated with anterior crossbites were corrected with orthodontic appliances. Methods: A 2 x 4 appliance and an upper removable appliance were used to correct the crossbites. Results: Correction of the anterior crossbites resulted in a clinical improvement of the gingival recession. The aetiology and management of localised gingival recession is discussed. Conclusions: Simple orthodontic appliances can be used to provide interceptive treatment to correct localised crossbite and enhance the overall long-term prognosis of the lower incisors. To achieve optimal results multidisciplinary involvement is recommended. (Aust Orthod J 2009; 25: 7681)

Received for publication: November 2008 Accepted: January 2009 Jadbinder Seehra: Jad_Seehra@hotmail.com Padhraig Fleming: padhraigfleming@hotmail.com Andrew DiBiase: Andrew.Dibiase@ekht.nhs.uk

Introduction

Gingival recession can be defined as the apical shift of the marginal gingiva from its normal position on the crown of the tooth to levels on the root surface beyond the cemento-enamel junction.1 The prevalence of gingival recession ranges from 7 per cent to 10 per cent in 7 to 15 year-olds.24 However, Ainamo et al.4 also reported gingival recession in 48 per cent and 72 per cent of 12 and 17 year-olds respectively in a Finnish sample. In the United Kingdom a 1 per cent incidence of true gingival recession within a sample of 15 year-olds has been reported.5 The varied prevalence rates may be attributed to variation in the age of the sample patients and ethnic groups studied, and the definitions and methods used to assess gingival recession.6,7 Indeed, Volchansky and Cleaton-Jones8

76

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 25 No. 1 May 2009

have suggested that gingival recession cannot be diagnosed with certainty before the age of 12 due to delay in maturation of the gingival tissues. In terms of individual distribution between teeth, the lower incisors are commonly affected in younger patients with both the canine and premolars affected in older children.4 The aetiology of gingival recession can be divided into developmental (predisposing) and acquired (precipitating) factors, but ultimately both act together to cause the destruction of the periodontium.6,7 Predisposing factors include labial displacement of teeth, width of the attached gingivae and a high frenal attachment, and precipitating factors include gingival trauma and poor oral hygiene. Labial displacement of teeth may develop due to ectopic eruption or dental crowding; such teeth

Australian Society of Orthodontists Inc. 2009

ORTHODONTIC TREATMENT OF LOCALISED GINGIVAL RECESSION

generally have a thin covering of alveolar bone on their labial surface covered by a correspondingly thin layer of keratinised mucosa or occasionally devoid of keratinised mucosa. These areas are therefore susceptible to bony dehiscence formation and gingival recession precipitated by periodontal disease and trauma; both Parfitt and Mjr2 and Stoner and Mazdyasna5 recorded increased gingival recession in labially positioned teeth. Conversely, AndlinSobocki9 reported in a 2-year longitudinal study that the amount of keratinised and attached gingiva may change following tooth movement in either a buccal or lingual direction. Lingually positioned teeth were associated with increased keratinised gingival width and a reduced clinical crown height. Lang and Loe10 reported at least 2 mm of keratinised gingiva, corresponding to 1 mm of attached gingiva, is required to maintain gingival health. A decreased width of mucosa will be prone to recession caused by mechanical and biological trauma i.e. toothbrushing and plaque retention. However, this association has been questioned by Freedman et al.11 who reported no difference in recession between sites devoid of attached mucosa and those which had up to 2 mm of attached mucosa present. In the presence of an inadequate zone of attached mucosa a high frenal attachment can pull the gingival tissues away from the tooth surface, allowing the accumulation of plaque leading to gingival inflammation and recession.12 An aggressive toothbrushing technique has been described as a precipitating factor in gingival recession. The high incidence of gingival recession reported by Ainamo et al.4 in both 12 and 17 yearolds was attributed to toothbrushing trauma. However, Zamet12 suggested both a bony dehiscence and thin keratinised mucosa are significant factors. Recently, lip piercings have been cited as causes of localised gingival recession.13 A cross-sectional study performed by Kapferer et al.14 reported a significant correlation between gingival recession and the time elapsed since placement of the piercing. This finding suggests chronic mechanical trauma as a significant aetiological factor. Occlusal trauma from an existing malocclusion can lead to gingival recession. An example of this is Class II division 2 malocclusion with an increased overbite where stripping of the labial mucosa of the mandibular incisors occurs; similarly, gingival recession palatal to the upper

incisors may also result from an impinging overbite.15 Inadequate plaque control leading to the accumulation of supra- and subgingival calculus may result in gingival recession.6 Conversely, gingival recession is also common in patients with excellent oral hygiene as a consequence of overzealous toothbrushing.16 A common clinical presentation of localised gingival recession is a prominent mandibular incisor with reduced or absent keratinised gingiva. Parfitt and Mjr2 reported the lower central incisors to be more commonly affected than the lower lateral incisors. Indications for treatment include: aesthetics, gingival inflammation/pocketing, sensitivity and root caries. We present and discuss two clinical cases in which severe localised gingival recession associated with localised anterior crossbites were treated using different orthodontic treatment modalities resulting in a clinical improvement in the gingival architecture.

Case 1

A medically fit and well 10 year-old male was initially referred to the orthodontic department by his general dental practitioner for advice regarding a reverse overjet involving the upper left central incisor (UL1) and severe gingival recession of the opposing lower left central incisor (LL1). The patient presented in the mixed dentition with a Class III incisor relationship (localised to the UL1) on a mild skeletal 3 pattern with a slightly increased lower facial height and maxillary mandibular planes angle. On examination both the upper and lower labial segments were retroclined with mild crowding. The UL1 was in crossbite; a reverse overjet of 1 mm was measured on the UL1 with no displacement on closure detected. Both maxillary canines were unerupted and palpated in the labial sulcus. Five millimetres of gingival recession was noted on the labial surface of the LL1 (Figure 1). However, no mobility of this tooth was detected. Oral hygiene was poor with generalised supragingival plaque deposits. A diagnosis of traumatic occlusion of the LL1 was made. Treatment aims included reinforcement of oral hygiene, correction of the localised anterior crossbite and prevention of further gingival recession of the LL1. Following banding of the UR6 and UL6, a preadjusted appliance (2 x 4 appliance), slot size 0.022 x 0.028 inch, with MBT prescription was bonded to the UR2, UR1 and UL2. A 0.014 inch NiTi archwire

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 25 No. 1 May 2009

77

SEEHRA ET AL

Figure 1. Case 1. Initial presentation of the severe localised gingival recession of LL1 and anterior crossbite.

Figure 2. The 2 x 4 sectional appliance. Steel tubing was placed in the buccal segments to support the flexible archwire. The UL1 was bonded following opening of the bite with glass ionomer cement.

Figure 3. At debond an improvement of the clinically appearance of the gingival height (LL1) is apparent.

Figure 4. Case 2. Presenting appearance of the severe localised gingival recession of LR1 and anterior crossbite.

Figure 5. Upper removable appliance in situ.

Figure 6. Improved clinical appearance of the gingival height of LR1.

was ligated and NiTi coil spring activated to open space for the UL1 at the first visit (Figure 2). At the following visit, glass ionomer build-ups were placed on the occlusal surfaces of both lower first molars. The UL1 was bonded and a 0.016 inch NiTi archwire ligated allowing unimpeded labial movement of the UL1 and achievement of a positive overjet and overbite. Overall treatment time was approximately 3 months, requiring 3 visits. At debond, an improvement in the position of the LL1 and gingival recession (3 mm) was noted (Figure 3). Both the patients dental development and the gingival health of the LL1 continue to be monitored.

Case 2

A medically fit and well 10 year-old male was referred to the orthodontic department by his general dental practitioner for advice regarding a localised anterior crossbite involving the upper right central incisor (UR1). The patient presented in the mixed dentition with a Class III incisor relationship (localised to the UR1) on a skeletal 1 pattern with an average lower facial height and maxillary-mandibular planes angle. On examination both the upper and lower labial seg78

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 25 No. 1 May 2009

ments were of average inclination with mild crowding of the upper labial segment. The UR1 was in crossbite; a reverse overjet of 1 mm was measured on the UR1 with displacement of UR1 on closure. Both maxillary canines were unerupted and palpated in the labial sulci. Intra-orally 3.5 mm of gingival recession was noted on the labial surface of the LR1 (Figure 4). Oral hygiene was of a poor standard with generalised supragingival plaque deposits. A diagnosis of traumatic occlusion of the lower right central incisor (LR1) was made. Treatment aims included reinforcement of oral hygiene, correction of the localised anterior crossbite (UR1) with removal of the displacement on closure and prevention of further gingival recession of the LR1. An upper removable appliance was constructed and fitted to correct the localised anterior crossbite (Figure 5). Both the retentive and active components of the appliance were reviewed on a monthly basis. Overall treatment time was 4 months requiring 6 visits. Following cessation of appliance therapy an improvement in the position of the LR1 and gingival recession (2.5 mm) was noted (Figure 6). Both the patients dental development and the gingival health

ORTHODONTIC TREATMENT OF LOCALISED GINGIVAL RECESSION

being generally well-aligned. The fixed appliance places a lesser premium on patient compliance, hence potentially reducing overall treatment time.17,18 In addition, retention is improved and easily achieved with the use of bonding agents rather than reliance on tooth undercuts. The documented cases both demonstrate gingival recession associated with a traumatic occlusion. However, it is unlikely that the severe degree of recession extending to the root surfaces exhibited in both cases is solely due to occlusal trauma. Plaque-induced gingival inflammation was a significant contributing factor in this aetiology. The clinical improvement resulted from lingual movement of the lower incisors following orthodontic correction of the localised crossbite. This was facilitated by orthodontic tooth movement in addition to improvement in oral hygiene and the absence of calculus deposits. The intimate relationship between levels of plaque control and presence of periodontal disease is well-established, while the clinical improvement in gingival inflammation and periodontal destruction is reliant on both preventive dental treatment and selfperformed plaque removal.19 Interestingly, Davies et al.19 reported that teeth in crossbite are also prone to greater plaque accumulation. In contrast, Andlin-Sobocki20 reported in a sample of children aged 613 years a reduction in gingival recession localised to the mandibular incisors when a high level of oral hygiene was maintained. At baseline an average of 2 mm gingival recession was present which reduced to 0.5 mm over a 3-year period; the value of optimal oral hygiene cannot be underestimated. Indeed, the difference in clinical improvement between the two cases may be attributed to a lesser improvement in oral hygiene by the patient in Case 2. In contrast, Eismann and Prusas21 reported that the mean improvement of the gingival level of orthodontically treated mandibular incisors in crossbite was 1.1 mm. Clearly it is difficult to differentiate between the effects of treatment and improved oral hygiene; however, it is extremely likely that these measures have a synergistic effect. When planning orthodontic treatment in these clinical situations the overall malocclusion should be considered, as highlighted by Case 1. In a mildly crowded case of this nature without associated periodontal destruction, treatment may have been postponed until the establishment of the permanent

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 25 No. 1 May 2009

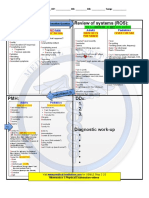

Figure 7. Diagrammatic view of modified URA used to correct the localised anterior crossbite in Case 2.

of the LR1 continue to be monitored. Oral hygiene instructions were reinforced.

Discussion

Classically, a removable appliance consisting of an acrylic baseplate, Adams cribs on the upper first permanent molars and premolars, a posterior bite plane and T-springs or Z-springs has been prescribed for the correction of a localised anterior crossbite. A similar design was used in Case 2. The design consisted of an acrylic baseplate, Adams cribs on the UR6 and UL6, ball-ended clasps between the contact points of the upper primary molars, bilateral posterior capping and a Z-spring palatal to the UR1 (Figure 7). Disadvantages of this type of appliance include the reliance on patient co-operation and compliance to wear the appliance and, critically, the teeth are only tipped and are not under the full control of the clinician. Another major issue is poor retention especially when used in the mixed dentition; this necessitated more regular recall culminating in more treatment visits compared to the sectional fixed appliance. The uses of the 2 x 4 appliance have been previously described by both McKeown and Sandler17 and Skeggs and Sandler.18 A sectional fixed appliance is ideal at providing interceptive treatment in the mixed dentition. The fixed appliance allows excellent control of the tooth in all three spatial planes. Consequently, a fixed appliance was chosen in Case 1 as more significant malalignment was present at the outset, necessitating space creation and controlled tooth movement. A removable appliance was preferred in Case 2 as the inclination of the UR1 was the chief problem with the upper labial segment

79

SEEHRA ET AL

dentition. The interceptive treatment performed in these cases is likely to be stable due to the attainment of a positive overbite following removal of the appliances (Figures 3 and 6). Furthermore, the absence of a significant sagittal skeletal discrepancy in either case ensures that further adverse mandibular growth resulting in recurrence of the anterior crossbite is unlikely. In the present cases, interceptive treatment was necessitated by the periodontal destruction, which had both aesthetic and dental health consequences. Placement of a lower appliance in the mixed dentition would, however, have been ineffective due to the likelihood of further lower incisor advancement due to the mandibular arch crowding. The long-term treatment plan in both cases includes maintenance of optimal oral hygiene and monitoring of both the developing occlusion and gingival level. The need for gingival surgery remains a possibility in both cases, although this would only be necessitated due to aesthetic concern or the development of sensitivity. Vergara and Caffesse22 reported excellent root coverage and an increased amount of keratinised gingiva using an envelope surgical technique in 50 consecutive patients with localised gingival recession. The benefits of guided tissue regeneration versus connective tissue grafts in the treatment of localised gingival recession have been investigated by Cetiner et al.23 with similar clinical outcomes reported for both techniques; however, connective tissue grafts resulted in greater levels of keratinised tissue. Whether surgical grafting should be performed before or after orthodontic tooth movement remains questionable. Maynard and Ochsenbein24 suggest that where insufficient (1 mm or less) keratinised tissue exists, a free gingival graft should be performed prior to orthodontic tooth movement. However, Ngan et al.25 reported that pre-orthodontic grafting of mandibular incisors with recession did not significantly further decrease the amount of post-orthodontic recession. In both cases gingival grafting was not considered before appliance therapy as greater than 1 mm of keratinised gingival tissue was present.

overall long-term prognosis of the lower incisors. To achieve optimal results multidisciplinary involvement is recommended.

Corresponding author

Mr Jadbinder Seehra Maxillofacial Unit Kent and Canterbury Hospital Ethelbert Road Canterbury Kent CT1 3NG United Kingdom Email: Jad_Seehra@hotmail.com

References

1. Le H, Anerud A, Boysen H. The natural history of periodontal disease in man: prevalence, severity, and extent of gingival recession. J Periodontol 1992;63:48995. Parfitt GJ and Mjr IA. A clinical evaluation of local gingival recession in children. J Dent Child 1964;31:25762. Younes SA, El Angbawi MF. Gingival recession in the mandibular central incisor region of Saudi schoolchildren aged 1015 years. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1983; 11:2469. Ainamo J, Paloheimo L, Nordblad A, Murtomaa H. Gingival recession in schoolchildren at 7, 12 and 17 years of age in Espoo, Finland. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1986;14: 2836. Stoner JE, Mazdyasna S. Gingival recession in the lower incisor region of 15-year-old subjects. J Periodontol 1980; 51:746. Geiger AM. Mucogingival problems and the movement of mandibular incisors: a clinical review. Am J Orthod 1980; 78:51127. McComb JL. Orthodontic treatment and isolated gingival recession: a review. Br J Orthod 1994;21:1519. Volchansky A, Cleaton-Jones P. The position of the gingival margin as expressed by clinical crown height in children aged 616 years. J Dent 1976;4:11622. Andlin-Sobocki A. Changes of facial gingival dimensions in children. A 2-year longitudinal study. J Clin Periodontol 1993;20:2128. Lang NP, Le H. The relationship between the width of keratinized gingiva and gingival health. J Periodontol 1972;43: 6237. Freedman AL, Salkin LM, Stein MD, Green K. A 10-year longitudinal study of untreated mucogingival defects. J Periodontol 1992;63:712. Zamet JS. The treatment of localized gingival recession. Dent Update 1980;7:41726. ODwyer JJ, Holmes A. Gingival recession due to trauma caused by a lower lip stud. Br Dent J 2002;192:6156. Kapferer I, Benesch T, Gregoric N, Ulm C, Hienz SA. Lip piercing: prevalence of associated gingival recession and contributing factors. A cross-sectional study. J Periodontal Res 2007;42:17783. Mitchell L. An Introduction to Orthodontics. 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007:114. OLeary TJ, Drake RB, Crump PP, Allen MF. The incidence of recession in young males: a further study. J Periodontol 1971;42:2647.

2. 3.

4.

5.

6.

7. 8.

9.

10.

11.

12. 13. 14.

Conclusions

The above cases demonstrate the diagnosis and management of localised gingival recession associated with an anterior crossbite. Two simple orthodontic appliances were used to provide interceptive treatment to correct the malocclusion and to enhance the

80

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 25 No. 1 May 2009

15. 16.

ORTHODONTIC TREATMENT OF LOCALISED GINGIVAL RECESSION

17. McKeown HF, Sandler J. The two by four appliance: a versatile appliance. Dent Update 2001;28:496500. 18. Skeggs RM, Sandler PJ. Rapid correction of anterior crossbite using a fixed appliance: a case report. Dent Update 2002;29:299302. 19. Davies TM, Shaw WC, Addy M, Dummer PM. The relationship of anterior overjet to plaque and gingivitis in children. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1988;93:3039. 20. Andlin-Sobocki A, Marcusson A, Persson M. 3-year observations on gingival recession in mandibular incisors in children. J Clin Periodontol 1991;18:1559. 21. Eismann D, Prusas R. Periodontal findings before and after orthodontic therapy in cases of incisor cross-bite. Eur J Orthod1990;12:2813. 22. Vergara JA, Caffesse RG. Localized gingival recessions treated with the original envelope technique: a report of 50 consecutive patients. J Periodontol 2004;75:1397403.

23. Cetiner D, Parlar A, Balos K, Alpar R. Comparative clinical study of connective tissue graft and two types of bioabsorbable barriers in the treatment of localized gingival recessions. J Periodontol 2003;74:1196205. 24. Maynard JG Jr, Ochsenbein C. Mucogingival problems, prevalence and therapy in children. J Periodontol 1975;46: 54352. 25. Ngan PW, Burch JG, Wei SH. Grafted and ungrafted labial gingival recession in pediatric orthodontic patients: effects of retraction and inflammation. Quintessence Int 1991;22: 10311.

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 25 No. 1 May 2009

81

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Oral Therapeutic and Diagnostic Devices Developed by SaliwellDocument25 paginiOral Therapeutic and Diagnostic Devices Developed by SaliwellIsrael ExporterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Giant Osteoma of MandibleDocument4 paginiGiant Osteoma of MandiblekadrologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Dual-Purpose Guide For Optimum Placement of Dental ImplantsDocument4 paginiA Dual-Purpose Guide For Optimum Placement of Dental ImplantskadrologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Stent For Pre Surgical Evaluation of ImplantDocument3 paginiA Stent For Pre Surgical Evaluation of ImplantkadrologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Dual-Purpose Guide For Optimum Placement of Dental ImplantsDocument4 paginiA Dual-Purpose Guide For Optimum Placement of Dental ImplantskadrologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Influence of Trans-Operative Complications OnDocument9 paginiInfluence of Trans-Operative Complications OnkadrologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dental Impaction Pain Model As A PotentialDocument9 paginiDental Impaction Pain Model As A PotentialkadrologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Herpes Simplex I and IIDocument50 paginiHerpes Simplex I and IItummalapalli venkateswara raoÎncă nu există evaluări

- UkraineDocument105 paginiUkraineÁngel García FerrerÎncă nu există evaluări

- New Records of Rhinolophus Beddomei Andersen, 1905 (Chiroptera - Rhinolophidae) From Central Peninsular Region of India, Including Echolocation Call Characteristics - MammaliaDocument5 paginiNew Records of Rhinolophus Beddomei Andersen, 1905 (Chiroptera - Rhinolophidae) From Central Peninsular Region of India, Including Echolocation Call Characteristics - MammaliaTariq AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Histology StainsDocument7 paginiHistology StainsFrozenMan100% (2)

- The American Museum of Natural History - Homo CapensisDocument26 paginiThe American Museum of Natural History - Homo Capensisandrefelipeppp100% (1)

- Gonorrhea SlidesDocument54 paginiGonorrhea SlidesYonathanHasudunganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Barbarians of Lemuria - Ancient Animals - Pdfbarbarians of Lemuria - Ancient AnimalsDocument9 paginiBarbarians of Lemuria - Ancient Animals - Pdfbarbarians of Lemuria - Ancient Animalsgevrin100% (1)

- Compre Hen SipDocument72 paginiCompre Hen SipChiyo Natha100% (1)

- Veterinary Nursing of Exotic PetsDocument1 paginăVeterinary Nursing of Exotic PetsMafexxÎncă nu există evaluări

- Saltin 2011 Skeletal Muscle Adaptability. Significance For Metabolism and Performance. Review.Document77 paginiSaltin 2011 Skeletal Muscle Adaptability. Significance For Metabolism and Performance. Review.Marko BrzakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beginning Reader For Students L1 To L6Document70 paginiBeginning Reader For Students L1 To L6DaveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Head and NeckDocument11 paginiHead and NeckdrsamnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grade 7 Biology Revision Worksheet II 2022Document5 paginiGrade 7 Biology Revision Worksheet II 2022Ishanee BoseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Testicular and Scrotal DisordersDocument127 paginiTesticular and Scrotal DisordersJean Fatima100% (1)

- Ras Nsi EncounterDocument3 paginiRas Nsi EncounterDanesh SurendranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Threatened and Endemic Wildlife of The PhilippinesDocument4 paginiThreatened and Endemic Wildlife of The PhilippinesGea May BrillantesÎncă nu există evaluări

- The History and Future of KAATSU TrainingDocument5 paginiThe History and Future of KAATSU TrainingRosaneLacerdaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Michigan's State SymbolsDocument2 paginiMichigan's State Symbolsnyc100% (5)

- Lrdi 100 PDFDocument101 paginiLrdi 100 PDFPuneet MalhotraÎncă nu există evaluări

- OSCE SkillsDocument9 paginiOSCE SkillsgoodbyethereÎncă nu există evaluări

- Questioner OAB PDFDocument6 paginiQuestioner OAB PDFMeizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Greek Gods and GoddessesDocument3 paginiGreek Gods and GoddessesKevin Macabanti100% (1)

- Science Form 2 Paper 1 Exam QuestionDocument10 paginiScience Form 2 Paper 1 Exam QuestionNorliyana Ali76% (25)

- Smoking Times Temperatures Chart 2018Document18 paginiSmoking Times Temperatures Chart 2018Jose JaramilloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Nervous SystemDocument69 paginiIntroduction To Nervous Systemadnan jan100% (1)

- PATHO 4-3 Diseases of The EsophagusDocument7 paginiPATHO 4-3 Diseases of The EsophagusMiguel Cuevas DolotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Breakfast - January 2016 PHDocument84 paginiBreakfast - January 2016 PHAnonymous e2GKJupÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Axial Skeleton PDFDocument9 paginiThe Axial Skeleton PDFElvin EzuanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Milma ProductsDocument3 paginiMilma ProductsSidharth BharathÎncă nu există evaluări

- CS Blue Sheet Mnemonics - USMLE Step 2 CS - WWW - MedicalDocument1 paginăCS Blue Sheet Mnemonics - USMLE Step 2 CS - WWW - MedicalMaya Seegers100% (1)