Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Shakespeare's Julius Caesar Analysis: Ambiguity, Theatrum Mundi, Stoicism

Încărcat de

The Human FictionDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Shakespeare's Julius Caesar Analysis: Ambiguity, Theatrum Mundi, Stoicism

Încărcat de

The Human FictionDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, Analysis: Ambiguity, Theatrum Mundi, Stoicism It's the bright day that brings forth

the adder -Julius Caesar Intro - Julius Caesar is different from other tragedies such as King Lear or Hamlet in that the tragic hero is not immediately clear, though it does have one. It is a more nuanced and ambiguous work, with each character being both good and bad. And while JC is a political commentary, reflecting the worries of civil war and succession in Shakespeare's own times, it's also peppered with philosophical reflections. The first time you read it, it may strike you as a cold tragedy, as Samuel Johnson said, due to this ambiguity and its less-quotable lines, but ultimately, I found it more enjoyable because of this initial impenetrability. Setting It's the year 44 B.C. The Roman Republic had survived for over 400 years. This time period is associated with freedom, but also class divisions between the patricians and plebeians, hence why it's interesting to see the people's tribunes (traditionally a plebeian office) at the beginning of the story, and why the conspirators are not revolutionaries: they seek only to restore the old status quo. While I believe it to be much earlier, the fall of the Republic is often dated with Caesar's death. Whatever the actual date, the period known as the Roman Empire always begins with Octavian/Augustus, first emperor as well as nephew and adoptive son of Caesar. We know by the historians that Shakespeare relied on that he would have seen this as a negative change, and very likely looked to the world around him and feared the same would happen to England. Julius Caesar There's a lot of history left out in this play, and there are many relevant things we don't see, such as our title character declaring himself the son of Venus. Meanwhile, Shakespeare chooses to highlight some more obscure aspects of Caesar's life such as his epilepsy and his wife's barrenness. Why is this? Given his belief that nature reflects human affairs, he clearly sees these facts as indicative of Caesar being unfit to rule, even a warning against him. Even in the Romans' own times these were considered heavenly curses. On the other hand, one of the most vital things we do get to hear about is Antony offering Caesar a crown, which Caesar three times refuses. But regardless of Caesar's dislike of outward signs of power, this is representative of his true position in Rome. In Shakespeare's eyes, and the eyes of the conspirators, this is an unjust situation that must be reversed. He puts the following words in Cassius's mouth: Why, man he doth bestride the narrow world / Like a Colossus, and we petty men / Walk under his huge legs and peep about. Interestingly Caesar dies in the middle of a speech in which he proclaims he's as constant as the northern star, / Of whose true fix'd and resting quality / There is no fellow in the firmament. However, Caesar's relationship with Brutus adds further dimension to his character. In the background of the play is the fact that Caesar is Brutus's father (in Shakespeare's mind). Though Caesar refuses the crown, Brutus says of him, I know no personal cause to spurn at him, But for the general. He would be crown'd: How that might change his nature, there's the question. In other words, nothing Caesar has done so far has merited death, except his own son's fear for the future. Brutus also says that his refusal is nothing but false humility, a strategic move to gain even more

power. And here enters one of the reasons we can have some sympathy for Caesar. Caesar, the flawed character that he is, does not see Brutus's betrayal coming, though he's astute enough to recognize it in Cassius. We also see him manipulated and mocked by Decius when he brags: But when I tell him he hates flatterers / He says he does, being then most flattered. Thus, on the one hand he's overly prideful, vain, and his own worst enemy, and on the other he's has only few people he can trust and is betrayed by those around him. Shakespeare does not make any single character a clear victim or a clear hero, nor all good or all bad, making it one of his more realistic tragedies; life is shades of gray. Brutus Nor is Brutus our tragic hero, though the strongest case can be made for him. First, he's the most illustrious representative of republicanism and manliness, as defined by courage, honor, and justice. Second, his life is quickly filled with suffering. We see him participate in his father's murder, his wife dies, as do many of his best friends, not to mention the 100 Senators killed by the Second Triumvirate. Finally, he commits suicide. To make matters worse, the conspiracy was in vain because it's ultimately Caesar's legitimate son, Octavian/Augustus who comes into power. It's all the more poignant because he's the descendent of the first Brutus, Junius Brutus, who was one of the main men who overthrew the Roman monarchy. The Republic started and ended with a Brutus. But Brutus is also a flawed character. He begins with a deep conviction that he simply must do what's right; there is no other choice, even if this means killing his father or his own death. But was this really Brutus's decision, or was he (like his father) the victim of manipulation? We see Cassius bend him to his will by flattery:And it is very much lamented, Brutus, / That you have no such mirrors as will turn / Your hidden worthiness into your eye. Casca says of him Oh, he sits high in all the people's hearts, / And that which would appear offence in us / His countenance, like richest alchemy, / Will change to virtue and to worthiness. In other words, Brutus is simply useful to him because he will mask their cruel actions; his name and reputation will blind the people, and Brutus is none the wiser. He shows the same poor judgment in dealing with Antony as Caesar had shown toward him, and he lets Antony give the funeral oration, culminating in Brutus fleeing Rome. Not only that, but all of the conspirators failed to plan for a post-assassination Rome. They never considered that the people would not rejoice for a return of the status quo. Cassius While Shakespeare had sympathy for the republican cause, Cassius is not one of our beloved characters. He not only deliberately ignores omens before the Battle of Philippi (a stupid and perilous action), but he's also portrayed as envious and greedy. We have Antony to make this explicit in the final scene of the play in which he states that Brutus was the only noble Roman involved, the rest motivated by vile motives. Even Octavian declares that he deserves a proper burial, but says nothing of Cassius. In the same scene in which Brutus is railing against Caesar, saying that he will be as an adder to Rome, he says: That lowliness is young ambition's ladder / Whereto the climber-upward turns his face: / But when he once attains the upmost round, / He then unto the ladder turns his back. Could this not actually refer to the dynamic between him and Cassius? Brutus is Cassius' ladder, and if he's motivated by greed, then woe unto Brutus. In another instance we see Cassius complain to Brutus that Caesar is now become a god, and Cassius

is / A wretched creature and must bend his body / If Caesar carelessly but nod on him. The third strike against him is when honest Brutus accuses him of taking a bribe. It's clear that Cassius is supposed to have ulterior motives. Even Caesar, blind to the machinations of Brutus and Decius, can easily see Cassius's rapaciousness. Thus, we're left to wonder if the entire time he's telling Brutus that it's him who should be in power, did he plan a power grab for himself? But, like Caesar, our all-too-human Cassius is not without his own poignant moments. He kills himself based on false knowledge, believing that Titinius, his close friend, was captured. In turn, Titinius kills himself when he sees Cassius dead (what friendship!). Caesar himself is not without some admiration for him: He reads too much / He is a great observer, and he looks / Quite through the deeds of men. Antony Antony shares this same ambiguity of character (surprise!) After Caesar's death he goes bravely to the conspirators and asks them to go ahead and kill him if that is their intent, painting a wretched picture. Nevertheless, despite his meek appearance, inwardly he's a beacon of manliness and honor in refusing to bow in submission. Swearing to avenge his friend's death, he cries out: O pardon me, thou bleeding piece of earth, / That I am meek and gentle with these butchers!...A curse shall light upon the limbs of men; / Domestic fury and fierce civil strife / Shall cumber all the parts of Italy. Antony is clearly more politically astute than Brutus. Playing on his appearance of meekness, he contrives the opportunity to give Caesar a public funeral oration. In doing this he turned a crowd predisposed to making Brutus their new king into a crowd that wanted to burn his house down, though this is not so difficult in Shakespeares world of the irrational mob. In any case, I think this scene highlights him as both the loyal friend and cruel avenger that he is capable of being. It's also vital to realize that where Brutus was so concerned with not seeming like a butcher and is content with Caesars death, the Second Triumvirate kills 100 senators, along with other men, including their own family members. Clearly, Antony wants more than revenge against certain individuals. He and Octavian have ambitions of their own. Tragic Hero - In the end, our viewpoints of the characters are ever balanced. Where Brutus kills his father, the imperial faction kills members of their own family. Where Casca mocks Brutus, Antony smears Lepidus. No one side is so much worse than the other. Further, though he views the masses in general as idiotic, Shakespeare seems to think that the distinction between the patricians and plebs was false, since they're capable of behavior just as base. For example, Caesar is just as easily manipulated by his wife and then Decius. Brutus as is goaded on by Cassius to kill his father. In fact, the entire plan was fairly slipshod: the conspirators thought that the entire universe would conspire to help realize their goals, never thinking things through about what would happen after his assassination. Cassius even says that it's not Caesar who has the falling sickness (epilepsy), it's them: No, Caesar hath it not. But you and I / And honest Casca, we have the falling sickness. And here it becomes crystal clear who the tragic hero is. It's Rome herself. The Republic has died. It's not only these main characters that will suffer; civil war wrecks havoc on all. And there has been no outside force; Romans have done it all to other Romans. I'm inclined to believe that Shakespeare was happy with the monarchy in his time, but he hated and feared civil war, of which England already had a lengthy history. In this light, an aging and childless monarch was not very comforting. But though he had his worries about the future, I think that he's advocating his world view far more than any particular course of action. Theatrum Mundi The world is a stage as he wrote in As You Like It: And all the men and women

are merely players. The stage never changes; the script never changes; only the actors change, and even these are more archetypes than individuals. On the small scale, this is seen in Antony's actions toward the end mirroring those of Brutus; he steps into his role. Even prior to this, the people who once loved Pompey eventually came to cry for his blood with the rise of Caesar. More recently in European history, the people once freedom fighters, having attained their rights, then proceed to model themselves after the upper class, and so goes history. It's an endless tragedy. An endless comedy. An endless game of King of the Hill. Thus, is the play really about human fallacy? The characters manipulate each other, lie, friendships cannot be counted on, lovers feel betrayed and left in the dark. It's the conjunction of human affairs that make up the tragedy; there's not one single tragic hero, nor victim, or villain, no matter how hard we may try to be any of these. The boundaries of the stage are the boundaries of the habitable universe. There is a tide in the affairs of men Which taken at the flood leads on the fortune; Omitted, all the voyage of their life Is bound in shallows and in miseries On such a full sea are we now afloat, And we must take the current when it serves, Or lose our ventures. Stoicism The final moral note is that of stoicism. I've talked before about how Shakespeare viewed human kindness as the redeeming feature of life. We do not see that in Julius Caesar. Instead, duty, honor, and a stoic indifference to your personal fate are seen as the redeeming features of life. Most notably, a number of the characters in the end commit suicide. From Casca's mouth: So can I / So every bondman in his own hand bears / The power to cancel his captivity. There are fates worse than death, such as the humiliation (or brutal death) they would have had to endure if captured by the 'imperial faction.' The Stoics would have heartily agreed. Furthermore, while the scene in which Brutus declares that the conspirators should not even need an oath to bind them to their duty is often twisted and contrived into some psychoanalytical explanation, it should be taken more at face value. He says: What need we any spur but our own case / To prick us to redress? What other bond / Than secret Romans that have spoke the word / And will not palter? This is eminently stoic; he needs no other reason than the justice of their cause, and felt that it would have been less noble if he had to rely on a thing as paltry as an oath to carry out his actions. He says that those who do need an oath to stay on their path are like the Old feeble carrions and such suffering souls / That welcome wrongs; unto bad causes swear. After all, as Caesar had said earlier in the play, Cowards die many times before their deaths; The valiant never taste of death but once. Of all the wonders that I have yet heard, It seems to me most strange that men should fear; Seeing that death, a necessary end, Will come when it come. *** Veni, Vidi, Vici

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Top 50 Russophobe Myths - Anatoly KarlinDocument29 paginiTop 50 Russophobe Myths - Anatoly KarlinLevantineAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet Analysis: Delusion, Division, FateDocument5 paginiShakespeare's Romeo and Juliet Analysis: Delusion, Division, FateThe Human FictionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Julius Caesar Play Summary & AnalysisDocument15 paginiJulius Caesar Play Summary & Analysispraveen181274100% (2)

- Survivors and Post-Genocide Justice in RwandaDocument140 paginiSurvivors and Post-Genocide Justice in Rwandasl.aswad8331Încă nu există evaluări

- Unit 9Document12 paginiUnit 9Jashan JanuhaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Julius Caesar Companion (Includes Study Guide, Complete Unabridged Book, Historical Context, Biography, and Character Index)De la EverandThe Julius Caesar Companion (Includes Study Guide, Complete Unabridged Book, Historical Context, Biography, and Character Index)Încă nu există evaluări

- Shakespeare's King Lear Analysis - Stoicism, Depression, RedemptionDocument5 paginiShakespeare's King Lear Analysis - Stoicism, Depression, RedemptionThe Human FictionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summary of Julius CaesarDocument5 paginiSummary of Julius CaesarRajHrishi DattaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spark Notes - Julius Caesar - Themes, Motifs & SymbolsDocument3 paginiSpark Notes - Julius Caesar - Themes, Motifs & SymbolsLeonis MyrtilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brutus Characer SketchDocument5 paginiBrutus Characer SketchRafiHunJian100% (2)

- Brutus' Conflicted Honor in Shakespeare's Julius CaesarDocument4 paginiBrutus' Conflicted Honor in Shakespeare's Julius CaesarbimboÎncă nu există evaluări

- Julius Caesar: by William ShakespeareDocument15 paginiJulius Caesar: by William Shakespearejantar mantar100% (1)

- Julius Caesar Plot SummaryDocument46 paginiJulius Caesar Plot SummaryShashank SaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Julius Caesar Plot Summary and Key DecisionsDocument4 paginiJulius Caesar Plot Summary and Key DecisionsRivaldo Cristiano FigueiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- BBC Shakespeare Unlocked Julius Caesar NotesDocument2 paginiBBC Shakespeare Unlocked Julius Caesar NotesdanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shakespeare's Julius Caesar Comprehension QuestionsDocument9 paginiShakespeare's Julius Caesar Comprehension Questionsmydawgdiana100% (1)

- Discuss Act IIIDocument8 paginiDiscuss Act IIIbats_robynÎncă nu există evaluări

- Samples of Book ReviewDocument16 paginiSamples of Book ReviewAmben Victoria100% (1)

- Making Sense of Julius Caesar! A Students Guide to Shakespeare's Play (Includes Study Guide, Biography, and Modern Retelling)De la EverandMaking Sense of Julius Caesar! A Students Guide to Shakespeare's Play (Includes Study Guide, Biography, and Modern Retelling)Încă nu există evaluări

- Shakespeare's Julius Caesar: A Political AssassinationDocument66 paginiShakespeare's Julius Caesar: A Political Assassinationkriskee13Încă nu există evaluări

- Digital Booklet - Somewhere Back in Time - The Best of 1980-1989Document14 paginiDigital Booklet - Somewhere Back in Time - The Best of 1980-1989Ricardo Rueda Minera100% (2)

- Analysis of Major CharactersDocument8 paginiAnalysis of Major Characterssuhail_912Încă nu există evaluări

- Brutus and Cassius - Tragic Flaws in Julius CaesarDocument8 paginiBrutus and Cassius - Tragic Flaws in Julius Caesarshanellethomas1820Încă nu există evaluări

- Character Chart Julius CaesarDocument4 paginiCharacter Chart Julius CaesarRyan Do100% (1)

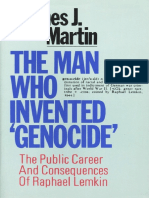

- The Man Who Invented 'Genocide': The Public Career and Consequences of Raphael Lemkin (1984)Document186 paginiThe Man Who Invented 'Genocide': The Public Career and Consequences of Raphael Lemkin (1984)Regular BookshelfÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nibelungenlied (Summary)Document1 paginăNibelungenlied (Summary)RuthÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gunnar S. Paulsson - The Rescue of Jews by Non-Jews in Nazi-Occupied PolandDocument3 paginiGunnar S. Paulsson - The Rescue of Jews by Non-Jews in Nazi-Occupied PolandRichard TylmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Ideas For Julius CaesarDocument8 paginiThesis Ideas For Julius Caesarfc5f5qej100% (2)

- Thesis Statement On Julius CaesarDocument7 paginiThesis Statement On Julius Caesarbk1f631r100% (1)

- Thesis Paper On Julius CaesarDocument4 paginiThesis Paper On Julius CaesarSara Alvarez100% (2)

- Julius Caesar Play SummaryDocument8 paginiJulius Caesar Play Summaryyanuariusrando100% (1)

- How To Write A Research Paper On Julius CaesarDocument5 paginiHow To Write A Research Paper On Julius Caesarh02pbr0x100% (1)

- JM Docgen No (Mar8)Document2 paginiJM Docgen No (Mar8)Ulquiorra CiferÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper On Julius CaesarDocument7 paginiResearch Paper On Julius Caesaregzh0913100% (1)

- Julio CesarDocument3 paginiJulio CesarmichaelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Play SummaryDocument7 paginiPlay SummaryMir LiyaqatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Statement For Julius Caesar EssayDocument6 paginiThesis Statement For Julius Caesar Essayabbyjohnsonmanchester100% (2)

- Thesis Statement For Julius CaesarDocument4 paginiThesis Statement For Julius Caesarpak0t0dynyj3100% (2)

- Julius Caesar Research Paper IntroductionDocument8 paginiJulius Caesar Research Paper Introductionafnhgewvmftbsm100% (3)

- Good Thesis Statement For Julius CaesarDocument6 paginiGood Thesis Statement For Julius Caesarafkololop100% (1)

- Thesis For Julius CaesarDocument4 paginiThesis For Julius CaesarMandy Brown100% (2)

- Cassius - Character SketchDocument2 paginiCassius - Character SketchAleena100% (1)

- Cassius's Manipulation of Brutus in Julius CaesarDocument2 paginiCassius's Manipulation of Brutus in Julius CaesarRoberto Luís ZehnderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Statement On Julius Caesar AssassinationDocument7 paginiThesis Statement On Julius Caesar Assassinationtcyzgiwff100% (1)

- English CourseworkDocument5 paginiEnglish CourseworkNaren CÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mahima Nidhi 21010323073 Div-A Ethics PaperDocument8 paginiMahima Nidhi 21010323073 Div-A Ethics PaperMAHIMA NIDHIÎncă nu există evaluări

- D2. Julius CaesarDocument5 paginiD2. Julius CaesarLavenderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shakespeare in The Ruins Presents JULIUS CAESARDocument27 paginiShakespeare in The Ruins Presents JULIUS CAESARLALITH NAIDUÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Paper Julius CaesarDocument8 paginiResearch Paper Julius Caesaraflbsjnbb100% (1)

- Notes For JC Fate Versus Free WillDocument4 paginiNotes For JC Fate Versus Free Willsand001287Încă nu există evaluări

- ACT 1 SC 3Document15 paginiACT 1 SC 3Swara BatheÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Spirit of CaesarDocument26 paginiThe Spirit of CaesarTed RichardsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Julius Caesar Act IIDocument8 paginiJulius Caesar Act IIAdham ZidanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Statement Examples Julius CaesarDocument4 paginiThesis Statement Examples Julius Caesartaradalymanchester100% (1)

- Good Thesis For Julius CaesarDocument4 paginiGood Thesis For Julius Caesarlidzckikd100% (2)

- Julius Caesar by William ShakespeareDocument2 paginiJulius Caesar by William ShakespeareRoxanne G. DomingoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Culture IV - Julius Caesar RevisadoDocument30 paginiCulture IV - Julius Caesar RevisadoMaria FilibertiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analyzing Brutus's Ultimate Downfall in Julius CaesarDocument6 paginiAnalyzing Brutus's Ultimate Downfall in Julius CaesarbriaaanaaaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conflicting Perspectives Julius Caesar ThesisDocument7 paginiConflicting Perspectives Julius Caesar Thesissamantharossomaha100% (2)

- First Written Between The Years 1600-01, First Performed in 1623. The Tragedy of Julius Caesar, Approx. 47 BC (An Early Tragedy)Document4 paginiFirst Written Between The Years 1600-01, First Performed in 1623. The Tragedy of Julius Caesar, Approx. 47 BC (An Early Tragedy)dyrandzÎncă nu există evaluări

- The End Justifies The MeansDocument4 paginiThe End Justifies The MeansYoussif ShaalanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Julius Caesar EssayDocument7 paginiJulius Caesar Essayapi-407728919Încă nu există evaluări

- Julius Caesar AnalysisDocument5 paginiJulius Caesar Analysisyoussef.mohamed.anwooÎncă nu există evaluări

- Julius Caesar EssayDocument3 paginiJulius Caesar Essayapi-255075145Încă nu există evaluări

- SCS Challenge 3 Comp 1 Julius CaesarDocument8 paginiSCS Challenge 3 Comp 1 Julius CaesarSarah Campbell SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final DraftDocument4 paginiFinal DraftAmman ChuhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Julius Caesar LitChartDocument30 paginiJulius Caesar LitChartCric FreakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Julius CaesarDocument4 paginiJulius CaesarSweta AgarwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pulp Fiction Analysis - Media Criticism, Manliness, Philosophy, DetachmentDocument3 paginiPulp Fiction Analysis - Media Criticism, Manliness, Philosophy, DetachmentThe Human FictionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shakespeare's Hamlet Analysis: Socrates, Nietzsche, Art, Absurdity, PoliticsDocument3 paginiShakespeare's Hamlet Analysis: Socrates, Nietzsche, Art, Absurdity, PoliticsThe Human FictionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mythology in InceptionDocument2 paginiMythology in InceptionThe Human FictionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clueless Movie Analysis (Brave New World Dystopia)Document2 paginiClueless Movie Analysis (Brave New World Dystopia)The Human FictionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shakespeare's Coriolanus Analysis: Fallacy, Faction, HonestyDocument6 paginiShakespeare's Coriolanus Analysis: Fallacy, Faction, HonestyThe Human FictionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shakespeare's Othello Analysis: Naievty, Misanthropy, ReputationDocument2 paginiShakespeare's Othello Analysis: Naievty, Misanthropy, ReputationThe Human FictionÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lessons From History: Parallels Between The Roman Kingdom and American ColoniesDocument21 paginiLessons From History: Parallels Between The Roman Kingdom and American ColoniesThe Human FictionÎncă nu există evaluări

- What is GenocideDocument30 paginiWhat is GenocideRon Andi RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Review of ''Blood Libel - The True Story of The Massacre at Deir Yassin''by Dr. Uri MilsteinDocument6 paginiA Review of ''Blood Libel - The True Story of The Massacre at Deir Yassin''by Dr. Uri MilsteinΚαταρα του ΧαμÎncă nu există evaluări

- Demographic Change in AbkhaziaDocument3 paginiDemographic Change in AbkhaziacircassianworldÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hotel Rwanda Questions and ReflectionDocument5 paginiHotel Rwanda Questions and ReflectionZzimmer34100% (1)

- The Holocaust - Wikipedia PDFDocument283 paginiThe Holocaust - Wikipedia PDFMuskan Aman100% (1)

- Bingel, Andrea. After Violence PDFDocument244 paginiBingel, Andrea. After Violence PDFDavid Muñoz AmbrizÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annihilating DifferenceDocument260 paginiAnnihilating Differenceguille1978Încă nu există evaluări

- 01-28-17 EditionDocument31 pagini01-28-17 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- En51b Unit2rdglog PoMcCab.Document5 paginiEn51b Unit2rdglog PoMcCab.Porter McCabeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crimes at Jasenovac Camp RevealedDocument74 paginiCrimes at Jasenovac Camp RevealedabosnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- UN's failure to prevent conflicts and uphold peaceDocument9 paginiUN's failure to prevent conflicts and uphold peaceshahÎncă nu există evaluări

- The 10 Stages of Genocide: 1. ClassificationDocument3 paginiThe 10 Stages of Genocide: 1. ClassificationMatheus ThalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- War and the City: Historical Perspectives on Urbicide and GenocideDocument15 paginiWar and the City: Historical Perspectives on Urbicide and GenocideMariel IvonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hotel Rwanda Reflection EssayDocument2 paginiHotel Rwanda Reflection EssayLouella Artel RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Liberian Daily Observer 04/08/2014Document16 paginiLiberian Daily Observer 04/08/2014Liberian Daily Observer NewspaperÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cynthia Parker WorksheetDocument2 paginiCynthia Parker Worksheetapi-276769930100% (1)

- Lame Termini Romani e GreciDocument3 paginiLame Termini Romani e GreciMax BergerÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Law PDFDocument18 paginiInternational Law PDFPer-Vito DansÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is PatriotismDocument2 paginiWhat Is PatriotismSeanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Swedish 40K Comp v1.73 - Army List TemplateDocument78 paginiSwedish 40K Comp v1.73 - Army List TemplatebaldergogÎncă nu există evaluări

- Game - of.Thrones.S06E09.1080p.hdtv.x264 BATV EngDocument81 paginiGame - of.Thrones.S06E09.1080p.hdtv.x264 BATV EngAnonymous H1yijrÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Hindu Genocides in Punjab During Khalistan Movement FacebookDocument6 paginiList of Hindu Genocides in Punjab During Khalistan Movement FacebookAmandeep singhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Picasso BackgroundDocument2 paginiPicasso BackgroundCharmianÎncă nu există evaluări