Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Pyron's Guide To Writing Essays

Încărcat de

josenmiamiTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Pyron's Guide To Writing Essays

Încărcat de

josenmiamiDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

PYRONS EASY GUIDE TO WRITING ESSAYS Darden Asbury Pyron Florida International University Miami, FL 33199 1.

Make a Thesis or Argument Every paper must make an argument. To make an argument, you must have read and analyzed the material and formed your own judgments about the facts. A thesis gives form. It functions like a blueprint does to an architect or builder. It provides the plan for your construction and allows the reader a standard by which to judge your intentions. You should be able to summarize any essay you write in a single paragraph or a sentence or two. 2. Avoid Description Descriptive papers assume the truth of the subject matter you present. A thesis-oriented paper takes a different tack. It assumes a variety of sources, often contradictory. You must weigh and evaluate the material and make the most plausible conclusion. 3. Introductory Paragraphs Avoid fluffy, flowery introductions. Make your introductions clear statements of what you intend to argue and how you intend to do so. Consider even the possibility of numbering the parts of your argument. Like this: Pericles dominated fifth century Athens. He exerted his influence in four major ways. . . . Then enumerate those ways. 4. Topic Sentences If the whole paper begins with a statement summarizing what should follow in general outline, each paragraph should begin with something comparable: a clear statement of the object of the individual paragraph. You begin with a good topic sentence and the rest of the paragraph sustains that lead with hard fact, evidence, and proofs. This defines the nature of the good paragraph. 5. Hard Evidence And Proofs You must always present evidence to support any argument or thesis you might make - whether of the whole paper or in individual paragraphs. Rely on the texts. Use quotations from the readings to prove your case. Use and cite the material upon which you base your writing. Topic sentences or generalizations not followed by supporting evidence have no place in these exercises.

6. Personal Judgments As per #5, these papers concern facts and the ordered arrangement of data. Whether you like those facts or not has little to do with good writing. In the absence of hard evidence, your personal opinion cannot advance your thesis. For this reason, never use the first person singular. By the same measure, the coupling of the first person with such verbs as feel and believe grossly compounds the error. Page 2 7. Argument by Analogy/Rhetorical Questions Beware of analogical arguments because what might seem an irrefutable reference to one person might seem false to another. At the same time, you have factual evidence enough without resorting to analogies. The same arguments discount rhetorical devices for proving a case as well. 8. One Sentence Paragraphs If the ideal paragraph presents a case (via a topic sentence) and then proves it with the data that follows, one sentence paragraphs fail by the very definition of the term. The usage possesses great popularity in contemporary newspaper writing, but it is the literary equivalent of advertising videos. Use them only, if ever, as a startling literary usage. 9. Keep Paragraphs Simple Aim for one major theme per paragraph. Dont crowd. 10. Extraneous Material In researching a topic you will find much that fascinates you that falls outside your thesis. Does the material not fit your thesis exactly? Lop it out. Either that or alter your thesis or make allowances within your topic sentences for such otherwise exceptional data. 11. Inter-Paragraph Logic Your paragraphs should flow in a natural, orderly fashion from one to another. The collection of your topic sentences together should provide a reasonable outline of your entire paper. 12. Intra-Paragraph Logic

The sentences within your paragraphs should also flow from one to another. Consider this way of connecting them in a natural flow. Sentences should imply questions like How? When? Why? or Where? During Jeffersons administration, the United States attained a new synthesis of politics and culture. This sentence implies all of the above questions except perhaps when. What follows, then, should answer these implied questions. Sometimes I write double slash marks when sentences fail to connect with each other. 13. Vary the Sentence Structure Within Your Paragraphs Try short sentences alternating with longer ones. Avoid using the same subject sentence after sentence. In some papers this might be a real test of your imagination, for example, when you chose a biographical subject, how do you avoid making Pericles or Jefferson the subject of every sentence? 14. Write Complete Sentences Each sentence must possess at least a subject and a predicate. Please!

Page 3 15. Keep Subjects and Predicates in Close Proximity This increases the force and power of your writing by making the direction of your sentences clear. Sometimes I will write numbers on your paper to indicate the degree of your sin in this matter. At present 53 words intervening between the subject and the predicate holds the record. 16. Subject-Verb Agreement The subject and verb must agree in number - plural subject demands plural verb, singular requires singular. Attention to Rule 15 helps eliminate this problem. 17. Compound Predicates This usage weakens the force of your sentence. Exercise caution. 18. Verb Tenses Follow a consistent pattern. In most historical papers, too, you generally use some version of the simple past tense, not the present.

19. Avoid would As a Part of Your Predicate Most folks use it incorrectly so generally avoid. 20. Use Strong, Active Verbs Your predicates carry the action. The stronger the verb, the more forceful your argument. If you make strong arguments, however, you must use strong evidence, remember. 21. Avoid to be Constructions A to be verb connotes no action at all but rather being. By this measure, the usage violates Rule 20. This weakness produces others. For example, this construction usually necessitates the use of additional clauses of one kind or another. This, in turn, slows the action of your sentence. Consider this, He is the man who won the foot race, versus this, The man won the foot race. 22. The Passive Voice Argh! As a general rule never allow the passive in your writing. The race was won by that man. Ugh. Why not, That man won the race. 23. There Is/There Are/It is Ugh. Such verbs and predicates possess no intrinsic meaning. They defer both subject and action. They demand a string of clauses if they are to have any meaning at all. Usually we use such constructions when we are not sure what we want to say or lack clarity about a given action. There are a great many things that bothered the wise man. In this sentence, the weak subject and verb necessitate the that clause. Lop out all three and the sentence makes sense on its own: A great many things bothered the wise man.

Page 4 24. Pronouns Make sure the pronoun reference is absolutely clear. Consider the following a violation of this rule: In Byrds History of the Dividing Line, he envisioned nature as the perfect state of order. No go, rather try: In History of the Dividing Line, Byrd envisioned nature. . . . The following doesnt work either: The next day Athens changed their mind. Instead try, The next day, the Athenians changed their mind.

25. Use As Few Words As Possible to Convey Any Idea Be direct. Strive for irrefutable data presented without folderole and fluff. The walls of Athens gave her all the protection she needed. The Athenian walls protected the city well. Here you exchange 7 words for 11. Whenever you see figures such as 7:11 I am indicating that you might cut your words by that ratio. This same rule applies in the case of Rules 22 and 23. Omitting there are. . .who constructions eliminates 3 unnecessary words off the top; avoiding the passive voice saves two words. 26. Tag-on Clauses and Run-on Sentences Your subjects and predicates should carry the weight of your logic and argument. Tag-on clauses dilute that force. Consider the following tangle: Orestes won the Olympic foot race that was run in the 47th Olympiad that featured the most notable win of all time when Alcibiades entered seven chariots winning first, second, and fourth places. Argh. This student writer crowds too much into one sentence. Simplify. Break it up. 27. Beware Even Of Prepositional Clauses See Rules 25 and 26. 28. Concessive Clauses Beware of clauses beginning with although, however, while, even but. These tend to throw the main line of your sentence off course. Use them, but too many compromise your thesis and make your writing jerky and insecure. Even if you use these terms, never open sentences with them. 29. Negatives and Negative Clauses Try to find a positive expression of an idea. He did not succeed in winning the race finds much more forceful expression in He failed to win the race or, better still, He lost the race. Note, too, as per Rule 25, you reduce the number of words without changing the meaning. Consider the greater clarity of the following change: Fear of revolts forced the Spartans into an entire reconstruction not only of their political system but of their culture as well versus Fear of revolts forced changes in the Spartan political system and altered Spartan culture as well. 30. Colloquialisms, Cliches, and Contractions Avoid all. Sometimes I might write talky on your papers; this constitutes a common error. Aim for concision and austerity in your prose. Write formally, avoid informality. Colloquialisms, cliches, and contractions all suggest informality.

Page 5 31. Possessives Get this right. The possessive of Pericles is Pericles not Pericles. Dont confuse its and its. Gods will is the will of one god; Gods will equals the possessive of more than one divinity. 32. On the other hand. . . . An especially overworked phrase. Conversely serves better. If you use it, make sure you include the first hand before you have another. 33. The fact that. . . . Another filler expression you should never use. 34. Parallelism in Sequences If you use a sequence, make sure its parts compare. He ran the race, fished the stream, and herded cattle provides a good example of parallelism. The parts must agree. 35. Exact Usage Find the exact word to carry the full weight of your meaning. If you doubt the proper meaning, use the dictionary or thesaurus. If you see the figure WW, you have used the WRONG WORD. 36. Idiot Words Please avoid such dopey, pop usages as lifestyle, feel, factor, finalize, and their ilk. To repeat, you aim for formal presentations in your writing exercises, not blurbs on MTV. 37. Spelling Is it necessary to elaborate this rule? 38. Repetition Check your prose. Make sure you vary your usage. Avoid using the same words or expressions to excess. 39. Adjectives and Adverbs Steer clear of both. Make your subjects and predicates carry the load of your sentences action, not the modifiers. They clutter your prose. The poor man ran very fast to answer the door lacks strength beside The wretch raced to the door.

Also adverbs especially prejudice your writing. Beginning a sentence with such horrors as Unfortunately, or Surprisingly, for example, attempts to influence the reader without offering a real argument. They raise more problems than they answer: Surprising to whom, the reader might ask; how unfortunate, the reader grumbles. Page 7 40. Titles, Books, Articles Underline book titles; put article titles in quotation marks. 41. Block Quotations Block indent quotations and use no quote marks only if the reference includes 50+ words. Otherwise, include the quotation within the body of the paragraph. Page 6 42. Quoting the Text Quotation to integrate into the text: Life is endlessly exciting. (Margaret Mitchell, Letters, p. 10) Option A: Margaret Mitchell said: Life is endlessly exciting. (Margaret Mitchell, Letters, p. 10) [Colon] Option B: Mitchell insisted that life is endlessly exciting. (Margaret Mitchell, Letters, p. 10) [Integrate into sentence.] Option C: According to Margaret Mitchell, life was endlessly exciting. [Paraphrase part and integrate into the sentence.] Option D: Margaret Mitchell always insisted that life was exciting. [Paraphrase entirely.] Watch your verbs especially in introducing quotations. Aim for strong, descriptive, but above all, accurate language; mentioned, believed, or felt, for example, hardly work in any circumstance, but they prove especially inept leads in introducing most quotations. Think instead, declared or other such aggressive words.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Writing Tips Revised September 2017 FINAL-1Document6 paginiWriting Tips Revised September 2017 FINAL-1Jon PearsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- 17 Academic Words and Phrases To Use in Your EssayDocument7 pagini17 Academic Words and Phrases To Use in Your EssayAladdin MahrousÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Write An Argumentative EssayDocument9 paginiHow To Write An Argumentative EssaysmwassyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis StatementDocument6 paginiThesis StatementaizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ten Tips On Writing A Good Theory of Knowledge Essay by Ric SimmsDocument2 paginiTen Tips On Writing A Good Theory of Knowledge Essay by Ric SimmsEvgeny DimitrovÎncă nu există evaluări

- Incorporating Research Into Your EssayDocument2 paginiIncorporating Research Into Your Essayapi-270621308Încă nu există evaluări

- How To Write An Essay: Part 1 of 5: A Step-by-Step Process For Writing An EssayDocument13 paginiHow To Write An Essay: Part 1 of 5: A Step-by-Step Process For Writing An EssayKeshav PrasadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Magic Thesis Statement FormulaDocument6 paginiMagic Thesis Statement Formulagbx272pg100% (1)

- How To Write An EssayDocument4 paginiHow To Write An EssaykatyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Developing Your ThesisDocument7 paginiDeveloping Your ThesismideseodecomunicarmeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Writing Concisely - The Writing Center - University of North Carolina at Chapel HillDocument3 paginiWriting Concisely - The Writing Center - University of North Carolina at Chapel HillTanimowo Abiodun SunkanmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases For TopDocument79 pagini40 Useful Words and Phrases For TopRandolf CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Write A Body of A Research PaperDocument12 paginiHow To Write A Body of A Research Paperkathleen SanchoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases For TopDocument97 pagini40 Useful Words and Phrases For TopAnonymous AnAEoNIeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Words To Use in Your IntroductionDocument10 paginiWords To Use in Your Introductionالصراحة راحةÎncă nu există evaluări

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases For TopDocument10 pagini40 Useful Words and Phrases For TopwinnieXDÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 5 Thesis Statement of An Academic Text: Prepared By: Ms. Andrealene L. GuilledoDocument16 paginiLesson 5 Thesis Statement of An Academic Text: Prepared By: Ms. Andrealene L. Guilledoandrealene guilledoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Otherness Thesis StatementDocument8 paginiOtherness Thesis Statementaliciastoddardprovo100% (1)

- Writing Concisely - From: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel HillDocument5 paginiWriting Concisely - From: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hillaehsgo2collegeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Is The Main Idea The Same As The ThesisDocument8 paginiIs The Main Idea The Same As The Thesisaflnoexvofebaf100% (2)

- Useful Phrases For Academic Essay WritingDocument7 paginiUseful Phrases For Academic Essay WritingJill SavelkoulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Writing IV Materi Inisiasi 1Document6 paginiWriting IV Materi Inisiasi 1Adam RizkyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases For Top-Notch EssaysDocument7 pagini40 Useful Words and Phrases For Top-Notch EssaysMaría Verónica Bérèterbide100% (1)

- ThesisDocument3 paginiThesisAbuela AbueloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Content and Style of The PaperDocument5 paginiContent and Style of The PaperdianaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1ST Page of StructureDocument4 pagini1ST Page of StructureMae Praxidio CarantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- EssayDocument12 paginiEssay梁梁柏Încă nu există evaluări

- A Guide To WritingDocument18 paginiA Guide To WritingOlga NancyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis PronunciationDocument4 paginiThesis PronunciationWritingServicesForCollegePapersSingapore100% (2)

- A Thesis Statement Must Be DebatableDocument5 paginiA Thesis Statement Must Be Debatablecrystalalvarezpasadena100% (2)

- EAPP Modules 5 and 6Document17 paginiEAPP Modules 5 and 6Keatelyn MogolÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Statement: How To Make It StrongerDocument7 paginiThesis Statement: How To Make It StrongerAdewaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Statement: How To Make It StrongerDocument7 paginiThesis Statement: How To Make It Strongercollins kirimiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reading Response Thesis StatementsDocument2 paginiReading Response Thesis StatementsFELIX CHENÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rubric - Definition or Exemplification - 6 - Ahed ZiqDocument3 paginiRubric - Definition or Exemplification - 6 - Ahed ZiqFadi Al ShhayedÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Makes A Good Literature Paper?: Keys To Success On The Synthesis EssayDocument25 paginiWhat Makes A Good Literature Paper?: Keys To Success On The Synthesis EssayWesley HsuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Features of An Academic PaperDocument40 paginiFeatures of An Academic PaperAlesha Isabel UyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis Statement of An Academic TextDocument21 paginiThesis Statement of An Academic TextNeil DumaanÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Write A Thesis Without Restating The QuestionDocument5 paginiHow To Write A Thesis Without Restating The Questionvictoriadillardpittsburgh100% (2)

- Convince Us of The Validity of Your ArgumentDocument2 paginiConvince Us of The Validity of Your ArgumentJohn JP BegovichÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research The Topic. Go Online, Head To The Library, or Search An AcademicDocument5 paginiResearch The Topic. Go Online, Head To The Library, or Search An Academicpichi94Încă nu există evaluări

- Academic Words and Phrases To Use in Your EssayDocument4 paginiAcademic Words and Phrases To Use in Your EssayInés PerazzaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Writing A Philosophy Paper: Peter HorbanDocument5 paginiWriting A Philosophy Paper: Peter HorbandunscotusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fix My Thesis StatementDocument8 paginiFix My Thesis Statementbrittanyeasonlowell100% (2)

- Thesis Statement of An Academic Text: Lesson 5Document15 paginiThesis Statement of An Academic Text: Lesson 5Vanessa NavarroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eapp Module 3Document4 paginiEapp Module 3Benson CornejaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analogy Thesis StatementDocument6 paginiAnalogy Thesis StatementPaySomeoneToWriteMyPaperGilbert100% (2)

- English For Academic and Professional Purposes Module 4Document13 paginiEnglish For Academic and Professional Purposes Module 4Irene TapangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thesis UmbrellaDocument4 paginiThesis UmbrellaNathan Mathis100% (1)

- Common Mistakes in Philosophy PapersDocument12 paginiCommon Mistakes in Philosophy PapersBen GibranÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Do You Write A Thesis For A History PaperDocument5 paginiHow Do You Write A Thesis For A History PaperBuyingPapersOnlineCollegeSingapore100% (2)

- How To Write A Good Interpretive Essay in Political PhilosophyDocument5 paginiHow To Write A Good Interpretive Essay in Political PhilosophyAniket MishraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Writing Philosophy PapersDocument5 paginiWriting Philosophy PapersSimón Palacios BriffaultÎncă nu există evaluări

- Example Thesis Statements For EssaysDocument10 paginiExample Thesis Statements For Essayshnjmwqlpd100% (1)

- 2020 - On The THESIS Statement & LinksDocument3 pagini2020 - On The THESIS Statement & LinksBelén DominguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1.1 Fundamental Principles of Legal WritingDocument21 pagini1.1 Fundamental Principles of Legal Writingbhattaaashish27Încă nu există evaluări

- Thesis StatementsDocument4 paginiThesis StatementsLaurithaletiixd3100% (1)

- 7 Deadly Sins ArgumentativeDocument4 pagini7 Deadly Sins ArgumentativeSaje BushÎncă nu există evaluări

- Favorite Passage Iliad 20-24Document1 paginăFavorite Passage Iliad 20-24josenmiamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Favorite Passages Iliad 6-10Document1 paginăFavorite Passages Iliad 6-10josenmiamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Euripides - Trojan Women The PlayDocument46 paginiEuripides - Trojan Women The Playjosenmiami100% (2)

- Spring of 2007 Deb's JourneyDocument4 paginiSpring of 2007 Deb's JourneyjosenmiamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Favorite Passage Iliad 20-24Document1 paginăFavorite Passage Iliad 20-24josenmiamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- FAVORITE PASSAGES The Iliad, Reading 1, Books 1-5. NAME - (You May Write It Out, or Copy and Attach) Be Prepared To Justify Your Selection in ClassDocument1 paginăFAVORITE PASSAGES The Iliad, Reading 1, Books 1-5. NAME - (You May Write It Out, or Copy and Attach) Be Prepared To Justify Your Selection in ClassjosenmiamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ch28 Lib Consensus 1960-68 50 SlidesDocument74 paginiCh28 Lib Consensus 1960-68 50 SlidesjosenmiamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Emotional Centers - AssociationsDocument1 paginăEmotional Centers - AssociationsjosenmiamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Favorite Passage Illiad 18-24Document1 paginăFavorite Passage Illiad 18-24josenmiamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ch25 WW2 80 SlidesDocument80 paginiCh25 WW2 80 SlidesJoseph HolbrookÎncă nu există evaluări

- Favorite Passages Iliad 6-12Document1 paginăFavorite Passages Iliad 6-12josenmiamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- WRITING 1 - Polybiis QuestionDocument3 paginiWRITING 1 - Polybiis QuestionjosenmiamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Favorite Passages Iliad 13-17Document2 paginiFavorite Passages Iliad 13-17josenmiamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Political Order in Polybius: EUH 2011, FALL 2011Document18 paginiPolitical Order in Polybius: EUH 2011, FALL 2011josenmiamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thanks To A CRI Travel Grant. - Havana December 2009Document13 paginiThanks To A CRI Travel Grant. - Havana December 2009josenmiamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- FAVORITE PASSAGES The Iliad, Reading 1, Books 1-5. NAME - (You May Write It Out, or Copy and Attach) Be Prepared To Justify Your Selection in ClassDocument1 paginăFAVORITE PASSAGES The Iliad, Reading 1, Books 1-5. NAME - (You May Write It Out, or Copy and Attach) Be Prepared To Justify Your Selection in ClassjosenmiamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- DEA Grant Writing PresentationDocument16 paginiDEA Grant Writing PresentationjosenmiamiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tugas RefalDocument13 paginiTugas RefalIswantoSakdiSidikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Class 5th EnlishDocument4 paginiClass 5th EnlishRajesh kuamrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Imperfective Paradox PaperDocument4 paginiImperfective Paradox PaperSirGoudaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cleft SentencesDocument2 paginiCleft SentencesRodrigo Cruz LantesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grammar Present Perfect TenseDocument3 paginiGrammar Present Perfect TenseKoo JuneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Present Perfect TenseDocument14 paginiPresent Perfect TenseJesslynTehÎncă nu există evaluări

- Passive Voice and Present PerfectDocument23 paginiPassive Voice and Present PerfectDaniela HolguinÎncă nu există evaluări

- GI A2PLUS Grammar Reference and PracticeDocument18 paginiGI A2PLUS Grammar Reference and PracticeArdaÎncă nu există evaluări

- English Level TestDocument4 paginiEnglish Level TestSoulaimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Task 1 Story WritingDocument3 paginiTask 1 Story Writingdeath riderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ready For Use of English Grammar: Some, Any, Much, Many, Little, Few, and A LotDocument3 paginiReady For Use of English Grammar: Some, Any, Much, Many, Little, Few, and A LotTierradelSurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Direct Indirect SpeechDocument9 paginiDirect Indirect SpeechSri DÎncă nu există evaluări

- Remedial PrelimsDocument4 paginiRemedial PrelimsLeo Dodi TesadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smart Time Special Edition Grade 11 Teachers Book WebDocument250 paginiSmart Time Special Edition Grade 11 Teachers Book Websttoms67% (9)

- Lexical Passive and Its Serbian Equivalents1Document6 paginiLexical Passive and Its Serbian Equivalents1aleksandra_rajicÎncă nu există evaluări

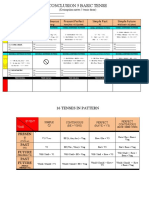

- Conclusion 5 Basic Tense: Simple Present Present Continuous Present Perfect Simple Past Simple FutureDocument2 paginiConclusion 5 Basic Tense: Simple Present Present Continuous Present Perfect Simple Past Simple FutureAdila Faila CassiopeiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conditional SentencesDocument6 paginiConditional SentencesRachit VishwakarmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparison of The AdjectivesDocument4 paginiComparison of The AdjectivesAndra VoicaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Godi (En Golbalen Plan Za Reazlizacija Na Nastavnata Programa Po Angliski Jazik Za Prvo Oddelenie Za U Ebnata 2015 - 2016 Struktura Na Godi (Niot Globalen PlanDocument2 paginiGodi (En Golbalen Plan Za Reazlizacija Na Nastavnata Programa Po Angliski Jazik Za Prvo Oddelenie Za U Ebnata 2015 - 2016 Struktura Na Godi (Niot Globalen PlanMartinNikolovskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- (SV - B1-B2) Active and Passive VoiceDocument5 pagini(SV - B1-B2) Active and Passive VoiceKaila WijayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 3: Conditionals: English TeamDocument11 paginiUnit 3: Conditionals: English TeamJonmy Altamirano MartinezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Variations On Polite Requests Using Conditionals, Modals and Fixed PhrasesDocument1 paginăVariations On Polite Requests Using Conditionals, Modals and Fixed PhraseslimlomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Progress Test 04Document1 paginăProgress Test 04Leo AriasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Expressing Ideas With VerbsDocument14 paginiExpressing Ideas With VerbsAirin RahmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercises: He Has Been Reading He Has ReadDocument1 paginăExercises: He Has Been Reading He Has ReadRomina AstridÎncă nu există evaluări

- SENTENCE PATTERN Noun Linking Verb AdverbialDocument4 paginiSENTENCE PATTERN Noun Linking Verb AdverbialDhittaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Active and Passive Voice Present Continuous GrammarDocument4 paginiActive and Passive Voice Present Continuous GrammarElizabeth MendozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reported Speech - SummaryDocument2 paginiReported Speech - SummaryFreddy Murrugarra100% (1)

- T15 The Expression of MannerDocument4 paginiT15 The Expression of MannerSanVaisen100% (1)

- Universidad Central Del Ecuador Language InstituteDocument1 paginăUniversidad Central Del Ecuador Language InstituteSolange YánezÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Importance of Being Earnest: Classic Tales EditionDe la EverandThe Importance of Being Earnest: Classic Tales EditionEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (44)

- The House at Pooh Corner - Winnie-the-Pooh Book #4 - UnabridgedDe la EverandThe House at Pooh Corner - Winnie-the-Pooh Book #4 - UnabridgedEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (5)

- You Can't Joke About That: Why Everything Is Funny, Nothing Is Sacred, and We're All in This TogetherDe la EverandYou Can't Joke About That: Why Everything Is Funny, Nothing Is Sacred, and We're All in This TogetherÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Inimitable Jeeves [Classic Tales Edition]De la EverandThe Inimitable Jeeves [Classic Tales Edition]Evaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (3)

- Welcome to the United States of Anxiety: Observations from a Reforming NeuroticDe la EverandWelcome to the United States of Anxiety: Observations from a Reforming NeuroticEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (10)

- Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs: A Low Culture ManifestoDe la EverandSex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs: A Low Culture ManifestoEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (1428)

- The Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee BookDe la EverandThe Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee BookEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (8)

- The Most Forbidden Knowledge: 151 Things NO ONE Should Know How to DoDe la EverandThe Most Forbidden Knowledge: 151 Things NO ONE Should Know How to DoEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (6)

- 1,001 Facts that Will Scare the S#*t Out of You: The Ultimate Bathroom ReaderDe la Everand1,001 Facts that Will Scare the S#*t Out of You: The Ultimate Bathroom ReaderEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (48)

- The Book of Bad:: Stuff You Should Know Unless You’re a PussyDe la EverandThe Book of Bad:: Stuff You Should Know Unless You’re a PussyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (3)

- Spoiler Alert: You're Gonna Die: Unveiling Death One Question at a TimeDe la EverandSpoiler Alert: You're Gonna Die: Unveiling Death One Question at a TimeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (58)

- Cats On The Run: a wickedly funny animal adventureDe la EverandCats On The Run: a wickedly funny animal adventureEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (8)

![The Inimitable Jeeves [Classic Tales Edition]](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/audiobook_square_badge/711420909/198x198/ba98be6b93/1712018618?v=1)