Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Overview of The Research Process

Încărcat de

Divine Barrion CuyaDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Overview of The Research Process

Încărcat de

Divine Barrion CuyaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Action Research Process Action Research can be powerful tool for teachers as they investigate, assess and

refine their teaching. It doesnt, however, have to be an onerous process that overwhelms an already overstretched teacher. Action research can be as simple as spending five to ten minutes at the end of each school day recording ones observations about the day. These observations can be revisited and reflected on every few weeks. The goal is to identify problems in the classroom or teaching method through reflection. In turn, the reflections should lead to new writing and the development of new strategies and solutions to bring into the classroom. Teachers must use action research in a way that suits their needs and not worry about following some rigid plan established by others. This section is intended to guide teachers as they create their own action research plan, but should not be seen as the only map in doing so. Overview of the Research Process Understanding the research process is important to your success in college. If you are new to the research process, this site will help guide you through the steps to completing a research assignment or complete research paper. There are several key steps involved in the research process, beginning with the selection of a research topic and the development of a tentative thesis, which is the argument that you will be defending in your research paper. If your instructor has not given you a topic, then you will have to go through the steps covered in the section finding a topic. After you've decided on a research topic, you can set out to find sources of supporting information. Such sources may include but are not limited to books, journal articles, newspapers, web sites, interviews, etc. Be sure to read the section on writing notes, a step that will later help in organizing material and properly documenting sources. The next main step in the research process involves the actual writing of the paper, report, or project. Working from your notes, you summarize, paraphrase, and incorporate direct quotes into a draft. This draft can undergo one or more content revisions before a final draft is completed. Next, it is essential that you "give credit" to your sources through endnotes, footnotes, a bibliography, or just simply a list of sources. As a final step, the written document should always be edited prior to submission. Understanding a Research Assignment Instructors in different disciplines will have different reasons for requiring you to write a research paper, and different expectations. Literature instructors might expect you to make judgments about the structure of a story or poem; science instructors might want you to gather evidence about the state of current research on medical or scientific topics. Scholarly writing in each discipline follows certain conventions or formats that are required for citing your sources and arranging your information. The society of language and literature scholars, the Modern Language Association, uses a set of guidelines known as MLA style. The American Psychological Association uses APA style. Some groups of scholars use a footnote system, while others use a numbering system. Your instructor should provide you with information about the particular style you should use in your research paper. Research Process The research process is a step-by-step process of developing a research paper. As you progress from one step to the next, it is commonly necessary to backup, revise, add additional material or even change your topic completely. This will depend on what you discover during your research. There are many reasons for adjusting your plan. For example, you may find that your topic is too broad and needs to be narrowed, sufficient information resources may not be available, what you learn may not support your thesis, or the size of the project does not fit the requirements.

The research process itself involves identifying, locating, assessing, analyzing, and then developing and expressing your ideas. These are the same skills you will need outside the academic world when you write a report or proposal for your boss. As these activities are frequently based on secondary sources from which recommendations or plans are formulated. Secondary sources are usually studies by other researchers. They describe, analyze, and/or evaluate information found in primary sources. By repackaging information, secondary sources make information more accessible. A few examples of secondary sources are books, journal and magazine articles, encyclopedias, dictionaries, handbooks, periodical indexes, etc. Primary sources are original works. These sources represent original thinking, report on discoveries, or share new information. Usually these represent the first formal appearance of original research. Primary sources include statistical data, manuscripts, surveys, speeches, biographies/autobiographies, diaries, oral histories, interviews, works or art and literature, research reports, government documents, computer programs, original documents( birth certificates, trial transcripts...) etc. How to Implement Action Research Teachers who conduct action research are: o Observers looking and looking again at what happens in the classroom, not necessarily for new information, but thinking about the information they already have; o Questioners problems encountered in the classroom become questions and opportunities to investigate. Everything that occurs in a classroom can be seen as data to be understood; o Learners the focus changes from What did you teach today? to What did you learn? Teaching becomes a process to model learning; o More Complete Teachers bringing together the concepts of knowing and doing. Questions to guide critical action research o What are the links between personal and social change? o How can teachers become challenges not only of their individually constructed assumptions but also of the larger social and political contexts that frame and often shape their work? o What are the internal and external inhibitors to teachers attempts to become challenges? o What does it mean to do our questioning in a collaborative fashion? o How can we work toward collaborative inquiry that includes a democratic approach that is equitable and consensual rather than merely participatory? o What are the relationships between and among reflection and action, teaching and research? Before you begin any project, it is essential to have a plan. Whether your project is a two page paper or a literature review, a research plan will help. Developing a plan will save time, stress and in the final analysis, yield a superior product. 1. Define your topic For topic ideas try the following: o Browse current/hot topics sites, such as CQ-Researcher, Topic Search, and Documents in the News o Browse current interest magazines or newspapers for stories of interest o Browse Encyclopedias or other reference books o Browse "10,000 Ideas for Term Papers, Projects, Reports and Speeches" (Ready Ref LB1047.3 L35 1998) o Listen to radio or television programs o Talk to people, such as teachers, friends

o One way to define your topic is to select a broad topic, then identify one or more sub topics you might like to explore. o Broad topic: _______________________________ Sub topic: ___________________________ Sub topic: ___________________________ Sub topic: ___________________________ Another approach is to select a topic, then list possible questions, such as... Who? What? Where? When? Why? How? 2. Write a thesis or problem statement: Begin with a question, research the topic further, then develop an opinion. 3. Make an outline. Even a quick one will help organize your thoughts and keep your research and your topic focused. 4. Develop a Search Strategy. Make a list of subject or keywords that might be useful in your search. Consider synonyms, such as hare and rabbit, or dog and canine. Alternate spellings are also common, try variations such as Athabascan, Athabaskan, Athapascan, or Athapaskan. Consider what the best sources for information you need might be. What type of information will you need? For tips on locating relevant sources see Library Search Strategy. books periodicals newspapers government documents biographical sources videos reference books: almanacs, etc. people (experts) archives/special collections Internet sources other? Consider where you would look for the sources you have selected: Goldmine (the UAF library catalog) or World Cat General periodical and newspaper indexes Alaska Periodical Index or other specialized periodical indexes Archives - finding aids, assistance from archives staff Expert knowledge (professionals, scientists, elders, etc.) Call agency/association Your aunt or uncle, the wildlife biologist Other? Always gather more information/citations than you think you might need. Some items might be missing, checked out, not owned, etc. If you get stumped ask for help at the REFERENCE DESK, ask a friend, or send your instructor an e-mail.

Remember the 15 minute rule -- if you've spent 15 minutes trying to figure something out in your research activities, ask for help. When searching online databases -- read the screens carefully and remember that it takes the same amount of time to find an article that is 1/8 of a page long as one that is 10 pages long -- use your time wisely. It may be that a smaller article gives you exactly the information you need, but if you're looking for extensive information, the longer article or the book will likely go into more depth on the topic, AND lead you to additional resources through its bibliographies. Take time to read the HELP or HOW TO SEARCH screens. Take advantage of Boolean searching and other searching tips to refine and improve the accuracy of your search. If you think you'll need assistance in your research try to use the library during times when there is a reference librarian at the Reference Desk.

5. Evaluate your sources. Evaluation begins as early as examining your first citation and continues through reading the information contained in the articles, documents, books, etc. that you consider using and making judgments on their authority, accuracy, objectivity, currency, and coverage. 6. Take careful notes. To save time, gather complete information the first time. Document your sources carefully and take notes (with page numbers). For each source that you consider using, gather the following information: If you do have to refer back to the source, it will save time if this information is readily available AND you will need it for your Bibliography or Works Cited list. For Books: Required citation elements are indicated in bold o Author: o Title: o Publisher (location, name, date): o Helpful information to relocate material, if necessary (optional): o Page numbers: o Call number (if any): o Subject you searched: o Persistent Link for electronic resources: For Articles: Required citation elements are indicated in bold o Article title: o Author's name (if any): o Title of periodical: o Volume & Issue number (if any): o Page numbers: o Date: o Helpful information to relocate material, if necessary (optional): o Call number of journal (if any): o Index searched: o Subject searched: o Persistent Link for electronic resources: 7. Writing and revising the paper. Allow plenty of time for the writing process. Your thesis and/or outline may need to be revised to reflect what was discovered during your research. 8. Document your sources. Give credit for the intellect work of others. Many citation style guides are available in print and via the Internet. If you are not sure which citation style is appropriate for your project/paper, check with your instructor.

The Seven Steps of the Research Process

The following seven steps outline a simple and effective strategy for finding information for a research paper and documenting the sources you find. Depending on your topic and your familiarity

with the library, you may need to rearrange or recycle these steps. Adapt this outline to your needs. We are ready to help you at every step in your research. STEP 1: IDENTIFY AND DEVELOP YOUR TOPIC SUMMARY: State your topic as a question. For example, if you are interested in finding out about use of alcoholic beverages by college students, you might pose the question, "What effect does use of alcoholic beverages have on the health of college students?" Identify the main concepts or keywords in your question. More details on how to identify and develop your topic. STEP 2: FIND BACKGROUND INFORMATION SUMMARY: Look up your keywords in the indexes to subject encyclopedias. Read articles in these encyclopedias to set the context for your research. Note any relevant items in the bibliographies at the end of the encyclopedia articles. Additional background information may be found in your lecture notes, textbooks, and reserve readings. More suggestions on how to find background information. STEP 3: USE CATALOGS TO FIND BOOKS AND MEDIA SUMMARY: Use guided keyword searching to find materials by topic or subject. Print or write down the citation (author, title, etc.) and the location information (call number and library). Note the circulation status. When you pull the book from the shelf, scan the bibliography for additional sources. Watch for book-length bibliographies and annual reviews on your subject; they list citations to hundreds of books and articles in one subject area. Check the standard subject subheading "-BIBLIOGRAPHIES," or titles beginning with Annual Review of... in the Cornell Library Classic Catalog. More detailed instructions for using catalogs to find books. STEP 4: USE INDEXES TO FIND PERIODICAL ARTICLES SUMMARY: Use periodical indexes and abstracts to find citations to articles. The indexes and abstracts may be in print or computer-based formats or both. Choose the indexes and format best suited to your particular topic; ask at the reference desk if you need help figuring out which index and format will be best. You can find periodical articles by the article author, title, or keyword by using the periodical indexes in the Library home page. If the full text is not linked in the index you are using, write down the citation from the index and search for the title of the periodical in the Cornell Library Classic Catalog. The catalog lists the print, microform, and electronic versions of periodicals at Cornell. How to find and use periodical indexes at Cornell. STEP 5: FIND INTERNET RESOURCES SUMMARY: Use search engines. Check to see if your class has a bibliography or research guide created by librarians. Finding Information on the Internet: A thorough tutorial from UC Berkeley. STEP 6: EVALUATE WHAT YOU FIND SUMMARY: See How to Critically Analyze Information Sources and Distinguishing Scholarly from Non-Scholarly Periodicals: A Checklist of Criteria for suggestions on evaluating the authority and quality of the books and articles you located. Watch on YouTube: Identifying scholarly journals Identifying substantive news sources If you have found too many or too few sources, you may need to narrow or broaden your topic. Check with a reference librarian or your instructor. When you're ready to write, here is an annotated list of books to help you organize, format, and write your paper. STEP 7: CITE WHAT YOU FIND USING A STANDARD FORMAT Give credit where credit is due; cite your sources.

Citing or documenting the sources used in your research serves two purposes, it gives proper credit to the authors of the materials used, and it allows those who are reading your work to duplicate your research and locate the sources that you have listed as references. Knowingly representing the work of others as your own is plagiarism. (See Cornell's Code of Academic Integrity). Use one of the styles listed below or another style approved by your instructor. Handouts summarizing the APA and MLA styles are available at Uris and Olin Reference.

Genara A. Perol

Secondary School Principal I

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Brian Tracy - How To Write EbookDocument15 paginiBrian Tracy - How To Write EbookRadim Holinka100% (8)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Ancient and Modern Britons Vol.1Document453 paginiAncient and Modern Britons Vol.1tbelote7100% (8)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The 30 Best Copywriting Books You Can Read in 2021Document18 paginiThe 30 Best Copywriting Books You Can Read in 2021Shawon Muntaha100% (8)

- Responding in Your Reader Response Journal: Sentence StartersDocument4 paginiResponding in Your Reader Response Journal: Sentence StartersAldanaVerónicaSpinozziÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1-TheSecrets - Walter F Print 2014-SECURED PDFDocument162 pagini1-TheSecrets - Walter F Print 2014-SECURED PDFganesha1905Încă nu există evaluări

- Salt Print With Descriptions of Orotone Opalotype Varnishes Historical and Alternative Photography by Peter Mrhar 1503302830 PDFDocument5 paginiSalt Print With Descriptions of Orotone Opalotype Varnishes Historical and Alternative Photography by Peter Mrhar 1503302830 PDFKéther Etz Chahim Jehu Alicia0% (1)

- TROPICO Strategy GuideDocument212 paginiTROPICO Strategy GuideMiloš PirivatrićÎncă nu există evaluări

- Open Foundation Creative Writing Course SampleDocument25 paginiOpen Foundation Creative Writing Course SampleAngela DizonÎncă nu există evaluări

- A2Z Features Glossary of School Management SoftwareDocument54 paginiA2Z Features Glossary of School Management SoftwarePriyanka GautamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Spring/Summer 2014 Frontlist Catalog - Children's/YA TitlesDocument57 paginiSpring/Summer 2014 Frontlist Catalog - Children's/YA TitlesConsortium Book Sales & DistributionÎncă nu există evaluări

- 3 Academic Writing Exploring Processes and StraDocument233 pagini3 Academic Writing Exploring Processes and StraMr Jameson100% (1)

- Captain Rosalie by Timothée de Fombelle Chapter SamplerDocument12 paginiCaptain Rosalie by Timothée de Fombelle Chapter SamplerCandlewick Press100% (1)

- Open كتاب دليل المدرس لمادة اللغة الانكليزية للثاني متوسط English for Iraq - H.K 2016Document172 paginiOpen كتاب دليل المدرس لمادة اللغة الانكليزية للثاني متوسط English for Iraq - H.K 2016Mustafa BaghdadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- American Political Science Association The American Political Science ReviewDocument3 paginiAmerican Political Science Association The American Political Science ReviewShannon TaylorÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Rozakis, Laurie) The Complete Idiot's Guide To Creative Writing PDFDocument386 pagini(Rozakis, Laurie) The Complete Idiot's Guide To Creative Writing PDFVicky Cabezacolorada0% (1)

- Bap 20 Sem.i Iii V PDFDocument16 paginiBap 20 Sem.i Iii V PDFConfucius Immortal RÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comic Books:Hidden Value: ExecrablyDocument6 paginiComic Books:Hidden Value: ExecrablyJavon KellymanÎncă nu există evaluări

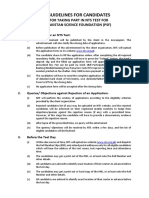

- Guidelines For CandidatesDocument5 paginiGuidelines For CandidatesAsad NawazÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Roaring Twenties Project 2Document5 paginiThe Roaring Twenties Project 2Carmen RoblesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Characteristics of Emergent ReadersDocument3 paginiCharacteristics of Emergent ReadersDon MateoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Impact of The Use of Online Resources Over Traditional Books As Learning Tool To Grade 12 Non-Health Students of University of Saint LouisDocument10 paginiThe Impact of The Use of Online Resources Over Traditional Books As Learning Tool To Grade 12 Non-Health Students of University of Saint LouisMarian Ivy BaltazarÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Lucky Ones by Linda Williams Jackson: Classroom Discussion GuideDocument40 paginiThe Lucky Ones by Linda Williams Jackson: Classroom Discussion GuideLinda Williams JacksonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ielts General Training Volume 3 - Listening Practice Test 1 v9 2357Document29 paginiIelts General Training Volume 3 - Listening Practice Test 1 v9 2357Artur BochkivskiyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Day 2 - True-False-Not GivenDocument11 paginiDay 2 - True-False-Not GivenDuong Gia Linh B2112435Încă nu există evaluări

- Q2 Mil-MotionDocument16 paginiQ2 Mil-MotionNon SyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marwa Al-Hammadi-Project PlanDocument25 paginiMarwa Al-Hammadi-Project Planapi-545693512Încă nu există evaluări

- A Book Management System ELibraryDocument54 paginiA Book Management System ELibraryJayaprada S. HiremathÎncă nu există evaluări

- Amber Books Illustrated Books Catalog 22Document66 paginiAmber Books Illustrated Books Catalog 22Amber Books LtdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Building An Effective Data Science PracticeDocument22 paginiBuilding An Effective Data Science PracticeFedhila AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Repeated Interactive Read-Alouds in Pre-School and KindergartenDocument11 paginiRepeated Interactive Read-Alouds in Pre-School and Kindergartenapi-533726217Încă nu există evaluări