Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Adult Education: The Role of Language in Trans Formative Learning and Spiritual Traditions

Încărcat de

Dianne AllenDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Adult Education: The Role of Language in Trans Formative Learning and Spiritual Traditions

Încărcat de

Dianne AllenDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Contemporary Issues in Adult Education Assignment Dianne Allen The Role of Language in Transformative Learning and Spiritual Traditions

The Role of Language in Transformative Learning and Spiritual Traditions

The Role of Language in Transformative Learning and Spiritual Traditions............................ 1 Overview: ............................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction: ........................................................................................................................... 2 The Role of Language in Transformative Learning - Mezirow's concept ............................. 3 The Role of Language in a Constructivist View of Knowledge Formation........................... 5 The Role of Language in a Spiritual Tradition ...................................................................... 6 Bringing These Three Strands Together - Implications for Learning and Education............ 7 A Personal Application .......................................................................................................... 8 Tower of Babel Genesis 11:1-9 - What principles this narrative conveys to me............. 8 A Personal Conclusion:........................................................................................................ 10 Bibliography......................................................................................................................... 11 ENDNOTES......................................................................................................................... 11

Dianne Allen, 2002

Contemporary Issues in Adult Education Assignment Dianne Allen The Role of Language in Transformative Learning and Spiritual Traditions

Overview: This paper explores the concept of 'transformative learning' as understood in contemporary education and spiritual traditions. It takes the view that the change that is aspired to in adult learning, adulthood, and the change aspired to in living the spiritual life, as understood in the Christian tradition involving conversion (salvation, redemption and sanctification), can be considered to be the same thing. That what appears to separate these views is a matter of language and the perception (at least in me) that different words are dealing with different things. Taking a constructivist stance, which has its origins in the discipline of hermeneutics, the process involved in interpreting sacred texts, allows us to understand the role of language, dialogue, and dialectic, in developing shared knowledge. With this understanding in place, an educator's approach to building knowledge in a corporate setting, and assisting all participants of an organisation to evaluate current corporate outcomes in the light of expressed corporate values can be considered to be an important, though difficult, task. With an enhanced understanding of these difficulties, their sources, and some alternative strategies to deal with them, such an educator can recommit themselves to this important task. Introduction: One of the issues that the conference on Contemporary Issues in Australian Education raised for me concerned the role of language, in education, in life, in transformation, in spiritual traditions. And for the question of in what way is the role language an issue, in these four areas, there were a number of different strands: What is the role of language in adult learning, in transformative learning in particular?; To what extent does the choice of language impact on our capacity to talk about the spiritual in a way that is (1) accessible, (2) does not raise estranging, excluding barriers, especially in the current societal silencing of a Christian witness?; What is meant by 'spiritual' to distinguish it from other categories? I find, as I look at first one, and then, another of these questions, and subordinate questions that develop from them, that the task of exploring the implications becomes steadily larger, and more than can be reasonably dealt with in the constraints of a typical, journal-size discussion. At this point I have a choice - to focus on only a couple of areas, to focus and go more deeply into one, or to stay at a more 'superficial' (or general) level and continue to address the complex that is the whole. Of these two routes, the reductive, analytical route appears to me to be the one over which I have most capacity to demonstrate a clear and contained line of discussion, one of the criteria of academic writing. This might explain why research, with its systematic inquiry, for the purpose of developing a reasonable base for understanding of a phenomenon and/or for the purpose of discerning reasonable actions to take, and with its public presentation of findings for open scrutiny by peers, more often than not follows a reductive, analytical path. Before I cut off the inquiry from the variety of strands possible, to focus on one alone, I would like to try and indicate what sorts of arguments, and reasons, I am attending to, that might suggest a capacity for synthesis, compared to reductive analysis. In thinking about the role of language in life, in education, in transformation and in spiritual traditions, there are at least three different sources of such concepts: my reading, my experience, and the current construction I have developed from those sources. From the documented, textual sources, I am focusing on three main items. The elements of a synthesis, comes from: firstly, Jack Mezirow's conception of transformative learning;

Contemporary Issues in Adult Education Assignment Dianne Allen The Role of Language in Transformative Learning and Spiritual Traditions

secondly, the role of language and dialogue in a constructivist view of human inquiry into aspects of humanness; and thirdly, the nature and content of the 'sacred text' of at least one spiritual tradition - the Bible in Christian life and witness. The Role of Language in Transformative Learning - Mezirow's concept One of Jack Mezirow's meaning perspectives, which represents a locus for change, and change which might be transformative, is the sociolinguistic perspective (Mezirow 1991). What does he mean by 'sociolinguistic perspective'? In his endeavour to explore and explicate what is going on in adult learning, and particularly in that learning which proves to have a transformative dimension, Mezirow enunciates a number of interactive components. He then goes on to provide a useful clarification of the distinction between formative learning and transformative learning. In his theorising (model-building) work on adult education, he seeks to identify four levels of change in learning. Firstly, he identifies four different categories of learning: (1) perception, prereflective learning (p.15); (2) comprehension learning through language (p.19) ; (3) meaning schemes specific beliefs, attitudes and emotional reactions articulated by an interpretation (p.35, see also p. 44 a meaning scheme is the particular knowledge, beliefs, value judgments, and feelings that become articulated in an interpretation'); and (4) meaning perspectives generalized sets of habitual expectation (p.34). Within Mezirows category of meaning perspectives, he identifies three different types (1) epistemic perspectives our assumptions about knowledge and knowing (p.43); (2) sociolinguistic perspectives assumptions developed by the nature of our language, or native tongue, and the social and cultural norms inculcated as a part of our socialisation (p.43); and (3) psychological perspectives assumptions developed from our experience of events in the world and their impact on our sense of safety or threat to our personal being and persisting (p.43). Then, working with Habermas analysis, Mezirow identifies three kinds of intentional learning: (1) instrumental (p.72); (2) communicative (p.75); (3) emancipatory (p.87). Mezirow also indicates that reflectivity, the process by which an adult engages in learning by and from their experience, involves examining assumptions and premises, of either the instrumental or the communicative domain (p.97). Mezirow then indicates that adult learning may assume any of the following four forms: (1) learning through existing meaning schemes; (2) learning new meaning schemes; (3) learning through the transformation of meaning schemes, and (4) learning through the transformation of meaning perspectives. (p.98) For Mezirow, as I understand him, transformative learning, the learning that is distinctively available to an adult, is learning that changes what has been established. There is learning that is formative - forming a construct of understanding in an individual. There is learning that is transformative - allowing for the reconstruction of the understanding of the individual in some fundamental way. That reconstruction can lead to not only a whole new way of perceiving life and the world we live in, but also to changes in the responses made to what is

Contemporary Issues in Adult Education Assignment Dianne Allen The Role of Language in Transformative Learning and Spiritual Traditions

going on in that world, what is often called lifestyle. For some, this change is both dramatic and pervasive, providing both a point of closure to 'the old' and a point of departure into the 'new'. For others, there appears to be a less dramatic sense of discontinuity, and the task of reforming attitudes and responses becomes a life-time's work as well as a new lifestyle approach. What is language's role in any such transformation? Firstly, it is with language that we learn to 'understand' our world. This is what Mezirow calls 'comprehension'. When I was teaching science, in my early professional life, one of my reflective evaluations of my responsibility and purpose in that task was that it involved developing the learner's vocabulary: what is a carbohydrate, a protein, a fat, a vitamin. These components were the stuff of food, of what was required for good nutrition, for health. As well as the words, there was knowledge, from chemical analysis techniques, of which components were found in which foods. There was knowledge, from other studies - historic records, public health surveys, that deficiencies, particularly of certain vitamins or trace elements, lead to preventable diseases like scurvy (the bane of the sailor on long sea voyages) and beri-beri. From this we could move to an understanding of a sound, balanced diet required for most effective living. But such knowledge is not always sufficient to counter the impact of advertising, of fashion, of perceptions of cultural mores. So now, in western affluent cultures, despite compulsory science education which involved tested knowledge of the stuff of foods and good nutrition, we are finding community-wide, public-health issues of difficulties with obesity, lifestyle diabetes, compulsive eating disorders, to name but three examples. Indeed, Mezirow indicates that sociolinguistic perspectives (like an understanding of the ideal body type for a woman, or a perception of the good life based on immediate sensual gratification, and the role of chocolate as the epitome of such luxury) established by multiple propaganda machines, operating sometimes on mutually contradictory bases, can be both a physical risk and a developmental risk where the distortion generated by them is one of the barriers to a full adulthood. Mezirow defines development in adulthood as 'movement towards ... a meaning perspective [which] is more inclusive, discriminating, integrative and permeable (open) than less developed ones' (p.193). He indicates that the path to such a point in development is via perspective transformation [which] is a social process: others precipitate the disorienting dilemma, provide us with alternative perspectives, provide support for change, participate in validating changed perspectives through rational discourse, and require new relationships to be worked out in the context of a new perspective. (p.194) One such example of a linguistic device which Mezirow gives, is that of naming individuals, working for a living, as 'labour', a more generalised, abstract term. This linguistic step can change perceptions. Labour, because it is now a resource, something that is only for the development of profit, of capital, like fuel, like other material entities, can apparently be handled on a different value scale than the usual moral obligations that underpin good social relationships. The personhood, of the individuals so named, with their human developmental capacities, is devalued and diminished. It is then only a short step to expendibility, to the fullest possible utilisation, which is exploitation and the social dis-eases of chronic underemployment of the individuals limited to a casual engagement in any work contract and/or overwork with stress and physical, mental or emotional breakdown. And in Australia, at this time, we have the apparent paradox of both of these dis-eases, in operation and at the same time.

Contemporary Issues in Adult Education Assignment Dianne Allen The Role of Language in Transformative Learning and Spiritual Traditions

The Role of Language in a Constructivist View of Knowledge Formation Mezirow's position on the transformative dimension of adult learning is clearly placed within a constructivist view of knowledge formation (p.4 and ff). Within such a view of knowledge formation, the role of language and dialogue is significant. Guba and Lincoln are recognised as having undertaken a definitive (and contested - eg Heron (Heron and Reason 1997)) enunciation of the constructivist view to knowledge formation in comparison with what they call the conventional view of 'positivism' (Guba and Lincoln 1985; Guba and Lincoln 1989; Guba and Lincoln 1994; Lincoln and Guba 2000). In Fourth Generation Evaluation, they indicate that the constructivist view is based on an ontology (the study of the nature of being) that asserts 'that there exist multiple, socially constructed realities ungoverned by natural laws, causal or otherwise'; that 'these constructions are devised by individuals as they attempt to make sense of their experiences'; that these experiences are interactive in nature; that 'phenomena are defined depending on the kind and amount of prior knowledge and the level of sophistication that the constructor brings to the task'; that 'constructions can be an usually are shared, ranging all the way from constructions about subatomic particles to those about cultural mores' (Guba and Lincoln 1989), (p.86). This ontology leads to an epistemology (the study of how we know what we know) that asserts that 'it is impossible to separate the inquirer from the inquired into'; it is the interaction of the inquirer and the inquired into that creates the data that will emerge from the inquiry. Consequently, the subjectivity of humans cannot be set aside. Nor are the values, held by the inquirer and the inquired into, dismissed and ignored. They are part of the stuff of the data of inquiry that must be attended to, to generate an 'informed and sophisticated construction on which there is consensus among individuals most competent to form such a construction' - the constructivist's understanding of the problematic nature of 'truth' (p.86, 88). Similarly, the constructivist ontology and epistemology, give rise to a constructivist methodology (the study of how we find out about things). Here it is asserted that 'inquiry must be carried out in a way that will expose the constructions of the variety of concerned parties, open each to critique in the terms of other constructions, and provide the opportunity for revised or entirely new constructions to emerge - a hermeneutic methodology' (p.89). Such a process is dependent on language, including defining terms; on dialogue which includes the dialectic to clarify meaning until commonly assented understandings are obtained, and where the revision of constructions, as a possibility amongst all parties to the investigation, is a pre-requisite to progressing to an authentic consensus. It is at these points that aspects of Piaget's move from the concrete to the abstract, and Vygotsky's concept of a zone of proximal development, come into play (srmehall? n.d.). And it is the use of language, and dialogue, in a social context, that are the chief mechanisms of such a change, such 'learning'. An example of the move from the concrete to the abstract, from 'I work', to 'people working', to 'labour', can also be the stuff of a sociolinguistic distortion. The role of a teacher, or adult, in working with another to help them move from one understanding to another level of sophistication in understanding, will often involve the non-conscious inculcation of associated and assumed values. These unconsciously absorbed values and their assumptions are then the stuff of a sociolinguistic (and perhaps also an epistemic and psychologic) meaning perspective which may need to be addressed in any endeavour to engage in transformative learning. The application of this constructivist view, in Guba and Lincoln's case, is into the field of evaluation. Here, people are engaged in reviewing the results of human activity, and

Contemporary Issues in Adult Education Assignment Dianne Allen The Role of Language in Transformative Learning and Spiritual Traditions

considering how else they might operate to achieve stated objectives, to enact and embody values in conjoint activity. It is here, in evaluation, that inquiry into human issues, with their ethical and political dimensions, becomes more attenuated, especially if the process of inquiry does not adequately cover all the dimensions of the human activity. In Guba and Lincoln's recommended process for their nominated 'fourth generation' evaluation, it is this constructivist methodology which also delivers on the necessity to be responsive to all the parties to any decision to change that might depend on the findings of that inquiry.

The Role of Language in a Spiritual Tradition As noted above, the constructivist view has its roots in the interpretive disciplines, one of which is hermeneutics, 'the term to denote the process of evolving successively more sophisticated interpretations of historical or sacred writings' (Guba and Lincoln 1989), (p.90). From a spiritual tradition, with its founding assumptions, the study of sacred texts is to interpret their meaning, to interpret the communications of a deity with humanity, to cross a divide, similar to that between two different language communities. Indeed, the English term 'translation', describing this process of enabling one language speaker to speak and share in another language community, has this 'movement' across a divide, or barrier, in mind. (Macquarie Dictionary: translate 1. To turn (something written or spoken) from one language into another 3. To bear, carry, or remove from one place to another (1997)). In the Christian tradition, one of the hermeneutic tasks is to deal with a text formulated in an historic and social context, and to discern the principles by which a believer in this day and age might endeavour to live, to reflect, contemporaneously, those principles (Stott 1992). I find it intriguing to note that language, words, the word, speaking, is something of a theme throughout the Bible. In Genesis (1:3,6,9,11,14,20,22,24,26) we see that 'God said' was the activity of creation. That while God named night and day, sky, land and sea, man named the animals, Genesis 1:5,8,10; Genesis 2;19-20. In Genesis 11 comes the story of the Tower of Babel about language: common language and conjoint endeavour, and the origin of multiple languages. In forming a covenant relationship with a people, we see, Exodus 20:1, that 'God spoke all these words' - and what follows are what is called the 10 Commandments. God's relationships with people, like Abraham, Jacob, Moses, and the prophets, are in terms of God taking the initiative and speaking. Sometimes such speech was mediated through a human form (Genesis 18:1-2, 32:24-30), sometimes dreams (Genesis 28:12-15; 37:5-7,9), sometimes voices with other manifestations (Exodus 3:2-4:17), sometimes other sorts of visions (1 Samuel 3; Isaiah 1, Isaiah 6:1-13; Jeremiah 14-19, Ezekiel 1:1, Daniel 7-12, etc). Personal relationship with God, from the human initiative, is described in terms of prayer, and words making explicit those yearnings (1 Samuel 1:10-14 and 2:1-10; Daniel 6:10-11 & 9:4-19). The words with which a prophet is claiming to speak for God need to be fulfilled before they are permitted to be binding for the believer (Deuteronomy 18:14-22). Then, in John 1, comes the 'Word became flesh' (John 1:1-18) where the claim is made that Jesus is God, incarnate. In the gospel records comes the statement that Jesus' teaching was recognised as the teaching of one with authority, not like the scribes, the teachers of the law (Matthew 7:29). It is sufficient for his word to do healing (Luke 7:1-10), to calm the storm (Matthew 8:23-27), to call the dead to life (John 11:38-44).

Contemporary Issues in Adult Education Assignment Dianne Allen The Role of Language in Transformative Learning and Spiritual Traditions

Bringing These Three Strands Together - Implications for Learning and Education On one hand, the reverse historical route will link these items together. The hermeneutic discipline and traditions of knowledge formation and/or interpretation of text, can be seen to develop into a constructivist view of knowledge and knowledge formation. Mezirow, in working at his insight of 'transformative learning' for some of the learning experience of women returning to adult studies, turns to the constructivist view to build his understanding of what is going on here. Such a constructivist view assists an educator think about what is trying to be achieved in an educative program, and how they might more effectively accomplish that. So, understanding the role of language in knowledge formation is an important step for an educator. Similarly, understanding the role of dialogue and dialectic in working with mental constructions, and building knowledge in a group, is an important frame of reference for an adult educator, especially when working in a corporate context, with corporate culture structures, and issues related to change in such understandings and structures. On another hand, the notion of life, and change through life, especially of a lifestyle change associated with a shift in meaning perspective, which may be leveraged through challenging assumptions in a sociolinguistic perspective, may be linked, in externalities at least, to either an educational program and experience, called 'transformative learning', or a spiritual experience, called 'conversion'. And one could take the view that, since in externalities the results are the same, the phenomenon, in its essence, is the same. As I understand it, this is the point at which 'faith' operates. Faith chooses to privilege one explanation over the other, and faith is exercised in either, and both, choices. Given that the role of language, and dialogue, and dialectic, are important aspects of an educator's tool box, I found Nelson's seminar paper 'Spiritual Traditions of Transformation' (2002) to be an interesting and compelling overview of the elements of spiritual traditions that relate to transformation. In that paper he noted: the experiential base of the spiritual; the notions of prophets, and priests, and congregation, with their different roles; the notions of the way, the journey, and the role of guides; and the notion of transformation, and the dimension of grace in that. He noted the emphasis, in spiritual traditions, on learning as a significant part of transformation, and the role of reflection in such a learning process. His input, together with John McIntyre's presentation of elements of Buddhist spiritual tradition, showed also how these features cross a number of different spiritual traditions. This highlighted for me, the question of the common ground of experience and meaning making, and then the issue of the separation of traditions into distinctive fields by the use of language: different terms are used, which seem to convey different phenomena. Again, I am tempted to diverge the exploration to look at: To what extent does the choice of language impact on our capacity to talk about the spiritual in a way that is (1) accessible, (2) does not raise estranging, excluding barriers, especially in the current societal silencing of a Christian witness?; What is meant by 'spiritual' to distinguish it from other categories? Instead, I need choose to focus, and I do so, on: what does the material to date have, by way of personal application for my practice as en educator, here and now?

Contemporary Issues in Adult Education Assignment Dianne Allen The Role of Language in Transformative Learning and Spiritual Traditions

A Personal Application I have recently become involved as a non-Executive Director with a small consulting company that is in the process of transforming its structure from a principal operator into a collaborative enterprise. This company is marketing itself as providing various services to organisations grappling with systemic change as a response to organisational, social and environmental issues. To achieve this, it is seeking to facilitate the development of participative and collaborative processes in learning, in planning and in forming action structures within organisations, and is endeavouring to accomplish this by a consciously constructivist concept of knowledge development. Again, for me the question arises: what do I understand to be the constructivist concept of knowledge development? And, given that understanding: how do I see it contributing to this aspect of corporate life? As noted earlier, the thrust of Guba & Lincoln's application of a constructivist view of evaluation lies in the argument that where the effectiveness of a corporate process, or situation, is under review, then all sources of available information need to be tapped. When the review is with a view to taking action, to change, to become more effective, then the range of values held by the participants needs to be acknowledged. Further, all the available information and the various values held by the parties to the activity need to be both evaluated and mobilised in order to craft a preferred route of action that many/most will be willing to follow through on. Part of the process of getting concerted action at the end of the inquiry will be determined by what has been accomplished in the process of the construction of shared knowledge and agreed conclusions that inform the intentional actions that are to follow. That process of construction of shared knowledge is accomplished in the activity of joint inquiry and it is premised on the principle of a constructivist view of knowledge formation. While this is a cogent argument for me, and one that is relatable to my experience, it also vies with a construct that I have that is informed by the Bible - the story of the Tower of Babel. Tower of Babel Genesis 11:1-9 - What principles this narrative conveys to me

11 Now the whole world had one language and a common speech. 2 As men moved eastward, a{ a Or from the east; or in the east} they found a plain in Shinar b{ b That is, Babylonia} and settled there. 3 They said to each other, Come, lets make bricks and bake them thoroughly. They used brick instead of stone, and tar for mortar. 4 Then they said, Come, let us build ourselves a city, with a tower that reaches to the heavens, so that we may make a name for ourselves and not be scattered over the face of the whole earth. 5 But the LORD came down to see the city and the tower that the men were building. 6 The LORD said, If as one people speaking the same language they have begun to do this, then nothing they plan to do will be impossible for them. 7 Come, let us go down and confuse their language so they will not understand each other. 8 So the LORD scattered them from there over all the earth, and they stopped building the city. 9 That is why it was called Babel c{ c That is, Babylon; Babel sounds like the Hebrew for confused.}because there the LORD confused the language of the whole world. From there the LORD scattered them over the face of the whole earth. The New International Version, (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House) 1984.

Contemporary Issues in Adult Education Assignment Dianne Allen The Role of Language in Transformative Learning and Spiritual Traditions

The context: The story of the Tower of Babel is placed in the biblical chronology after Noah and the flood (Genesis 6-10), and before the call of Abraham and the setting apart of Abraham and his family as the covenant people (Genesis 12-17-25) and the forefather of a faith community (Galatians 3:6). In the terms of biblical theology - how the Bible unfolds the revelation of the character of God and his creation, the nature of man in that creation, and Gods persistence in seeking to redeem a people who will live in a way that reflects his character (as made in his image) - it is the last significant event of the cosmology, the big picture, of creation and human kind and society, before the focusing on the individual i . It gives an explanation for multiple languages from a common stock. It is an illustration of a holy and just God exercising mercy in dealing with that which challenges and destroys what was the good in his creative work. Earlier, a flood was used to destroy all but Noah and his family and the animals gathered into the ark, to deal with the escalation of the impact of sin (missing the mark) and transgression (overstepping the boundaries). Now, confusion of language is used to limit the capacity for conjoint activity which expresses human pride in the face of a more reality-based, humble, relationship with God. The implications: A premise on which I operate, when using the bible to inform my approach to life, is that the bible has, in it, the revelation of God, of Himself, and of His nature and ways. Without such a revelation, such self-disclosure, I cannot hope to know God. As with another person, without accurate knowledge of God's nature I cannot effectively relate to God. As such a revelation, it states it provides sufficient information to know how to live a life of purpose, fullness, and blessing (Deuteronomy 30:11-16). There are other things to be known about God (Deuteronomy 29:29), but the revealed material is sufficient for living the good life. Some would term this as salvation right knowledge of God, for a right relationship with God humble obedience. Apart from the premise of its source being from God, I consider the wisdom of the bible to be supported by what I consider to be a significant warrant. It is that many people, down through the ages, give a witness to having tested the truth of its claims in their lives and to have found it a source of wisdom, of advice, for the living of the good life. Indeed, there are challenges and invitations to test it in that way (Psalm 34:8; Malachi 3:10; Romans 12:2). People have found that, in its narratives of personal lives and key points and transitions in those lives, in its laws and precepts, its poetry and prophecy, there are principles that can be tapped, by reading, by meditation, by prayerful consideration of its content, and looking for directions for living ii . It deals with the whole life: a person's relationship with God; and with other people, at an individual, family and community, even national, level (Romans 12:1-13:14). It deals with a person's relationship with the created order - biosphere and material universe (Romans 8:1827); and with the spiritual realm of principalities and powers (Ephesians 6:10-18). As a written document it is available for continued and continual consultation. When it is attended to, perhaps even memorised, as encouraged in Deuteronomy 6:6-9, and revisited, its perceptive frame provides an antidote to loss of its particular kind of focus, its lens on life and wisdom.

Contemporary Issues in Adult Education Assignment Dianne Allen The Role of Language in Transformative Learning and Spiritual Traditions

10

When the bible is attended to with an eye for principle, and an active capacity to re-interpret these principles to the kind of practice which is relevant to current social conditions, and used as the base of a community of practice, it has been a source of renewal. That renewal has included moving individuals, families, communities, even nations, to living relationships that are freer of gross oppression than relationships not so examined. An example of this is seen in England and the de-institutionalising of slavery and the exploitation of child labour (Wilberforce, 1759-1833 Shaftesbury, 1801-1885 respectively). So, the story of the Tower of Babel has a wisdom lesson for those with ears to hear. To me it says that one of the consequences of disobedience of God is a difficulty with communication and conjoint activity. A corollary of that is: that part of the process of salvation, redemption, and sanctification, is to reverse this trend. People who are looking for the kingdom of God, and endeavouring to live in the kingdom of God, will be working on obedient living that includes working on clear and respectful communication to develop relationships toward and with God, toward and with neighbour, and toward and with Christian peers (for example: Ephesians 5:1-6:20). Further, the Tower of Babel explains much of the frustration of effort in a corporate activity, and, together with the rest of biblical theology about new birth into a new life, holds out the potential of transformation. The basis of such transformation, to reverse the present frustration, is in a life lived in willing obedience to God. The relationship with God needs to be fixed first iii .

A Personal Conclusion: On one level, I am drawn to the teaching of the Tower of Babel and have a pessimistic view of the potential to use the constructivist concept of knowledge formation to make a great deal of progress in corporate life. On the other hand, knowing this about the nature of language, and frustrations that arise because of it, I can also move my understanding from an idealistic position to a more realistic position. Instead of just experiencing frustration, I can engage, or not, with the kind of work that needs to be done to build a common understanding. Knowing what that work involves and what the hazards are in it, will allow me to persevere in the task, if the goal is significant enough. If the goal is God-honouring, then there is some hope of attaining it. That is the construct of my faith at this stage. And it also gives me a tool to evaluate a goal, the purpose to which I direct my effort, from those destined to frustration to those more life-giving. Further, in corporate life, in my currently developing role as a possible facilitator of 'participative and collaborative processes: in learning, in planning and in forming action structures within organisations', and 'endeavouring to accomplish this by a consciously constructivist concept of knowledge development', this understanding of the foundations and principles of such an approach, is essential. Again, it will help to keep me on task when the going gets tough. I can explain to participants why it is a priority, and how it does and doesn't work. Such an understanding, when shared, has the potential to inform the constructed understanding of other participants, and to help them consider their choices and the reasons for their decisions in making a choice about persisting or not.

Contemporary Issues in Adult Education Assignment Dianne Allen The Role of Language in Transformative Learning and Spiritual Traditions

11

Bibliography:

(1986). The Student Bible: New International Version. Grand Rapids, Mich, Zondervan. (1997). The Macquarie Dictionary. Ryde, NSW, Macquarie University. Guba, E. G. and Y. Lincoln (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA, Sage. Guba, E. G. and Y. Lincoln (1989). Fourth Generation Evaluation. Newbury Park, CA, Sage. Guba, E. G. and Y. Lincoln (1994). Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research. Handbook of Qualitative Research. N. K. Denzin and Y. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks, Calif., Sage: 105-117. Heron, J. and P. Reason (1997). A participatory inquiry paradigm. Qualitative Inquiry 3(3): 274(21). Lincoln, Y. and E. G. Guba (2000). Paradigmatic Controversies, Contradictions, and Emerging Confluences. The handbook of qualitative research. N. K. Denzin and Y. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks, Calif., Sage: 163-188. Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass. srmehall? (n.d.). Social constructivism. 2002. Stott, J. (1992). The Contemporary Christian: an urgent plea for double listening. Leicester, Inter-Varsity Press.

ENDNOTES:

i

My thinking. Supported in part by Commentary in the (1986). The Student Bible: New International Version. Grand Rapids, Mich, Zondervan. ii I note that others include history, and rational thought, as further warrants, beyond personal and vicarious experience, eg Schuaffele and Baptiste cited in Nelson's seminar paper. iii It seems to me to be no accident that one of the descriptors given to Jesus, the one whose propitiatory death makes possible a restoration of relationship with God (John 3:16-18), is The Word (John 1:1-18).

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Role Play in Training For Clinical Psychology Practice - Investing To Increase Educative OutcomesDocument19 paginiRole Play in Training For Clinical Psychology Practice - Investing To Increase Educative OutcomesDianne Allen100% (3)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Dispute Resolution: Nature of Conflict & Its Role in SocietyDocument139 paginiDispute Resolution: Nature of Conflict & Its Role in SocietyDianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Educative Process - Design of EDUT 422 2004Document2 paginiEducative Process - Design of EDUT 422 2004Dianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Dispute Resolution: Industrial Dispute Resolution Issues, Trends and ImplicationsDocument81 paginiDispute Resolution: Industrial Dispute Resolution Issues, Trends and ImplicationsDianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Dispute Resolution: Lessons To Be Learned From The Experience of Disputes in The Construction IndustryDocument63 paginiDispute Resolution: Lessons To Be Learned From The Experience of Disputes in The Construction IndustryDianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- How Can I Use The Research ApproachesDocument1 paginăHow Can I Use The Research ApproachesDianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Dispute Resolution: Resources For Strategic InterventionsDocument38 paginiDispute Resolution: Resources For Strategic InterventionsDianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- MEd: Research Perspective in EducationDocument4 paginiMEd: Research Perspective in EducationDianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- Adult Education: Scaffolding For Adult Learners Working With Learning To ChangeDocument10 paginiAdult Education: Scaffolding For Adult Learners Working With Learning To ChangeDianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- MEd: Design A Research StrategyDocument14 paginiMEd: Design A Research StrategyDianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- MEd: Argue Problem and MethodDocument19 paginiMEd: Argue Problem and MethodDianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Analysis of Types of Inquiry For Improving Educational PracticeDocument1 paginăAnalysis of Types of Inquiry For Improving Educational PracticeDianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Total Bibliography 2005 (Dianne Allen)Document38 paginiTotal Bibliography 2005 (Dianne Allen)Dianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Christ's People and Society, 1974, 2011Document39 paginiChrist's People and Society, 1974, 2011Dianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Reflective Practice Select Bibliography 1998Document11 paginiReflective Practice Select Bibliography 1998Dianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reflective Practice Student Notes 1998Document8 paginiReflective Practice Student Notes 1998Dianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Reflective Research of Practice EXTENDED NOTESDocument68 paginiReflective Research of Practice EXTENDED NOTESDianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Converging On The ComplexDocument3 paginiConverging On The ComplexDianne AllenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Love Hans Urs Von Balthasar TextDocument2 paginiLove Hans Urs Von Balthasar TextPedro Augusto Fernandes Palmeira100% (4)

- CH 10.5: Separation of Variables Heat Conduction in A RodDocument20 paginiCH 10.5: Separation of Variables Heat Conduction in A RodArial96Încă nu există evaluări

- Strategic Thinking Part1Document15 paginiStrategic Thinking Part1ektasharma123Încă nu există evaluări

- LiberalismDocument2 paginiLiberalismMicah Kristine Villalobos100% (1)

- Robinhood Assignment 1Document4 paginiRobinhood Assignment 1Melchor P Genada JrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exercises On Parallel StructureDocument2 paginiExercises On Parallel StructureAviance JenkinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Learning To Memories Script at SchoolDocument3 paginiLearning To Memories Script at SchoolJen VenidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nouns Lesson Plan-NSC FormatDocument3 paginiNouns Lesson Plan-NSC FormatJordyn BarberÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marriage As Social InstitutionDocument9 paginiMarriage As Social InstitutionTons MedinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Times of League NovemberDocument7 paginiThe Times of League NovembermuslimleaguetnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project On Central Coal FieldDocument100 paginiProject On Central Coal Fieldankitghosh73% (11)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Object Oriented ABAP GuideDocument40 paginiObject Oriented ABAP Guidenavabhatt100% (3)

- Miss Evers BoysDocument5 paginiMiss Evers BoysMandy Pandy GÎncă nu există evaluări

- Coach Evaluation FormDocument2 paginiCoach Evaluation Formapi-314123459Încă nu există evaluări

- Islamic ColonialDocument4 paginiIslamic ColonialMargarette Ramos NatividadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cdvs in The NewsDocument3 paginiCdvs in The Newsapi-250757402Încă nu există evaluări

- Degenne, Forsé, 1999 - Introducing Social NetworksDocument257 paginiDegenne, Forsé, 1999 - Introducing Social NetworksGabriel Cabral BernardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Awp 2Document6 paginiAwp 2api-35188387050% (2)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Forgiveness Forgiveness Forgiveness Forgiveness: Memory VerseDocument5 paginiForgiveness Forgiveness Forgiveness Forgiveness: Memory VerseKebutuhan Rumah MurahÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Analysis of A Heritage of Smallness by Nick JoaquinDocument3 paginiAn Analysis of A Heritage of Smallness by Nick JoaquinAlvin MercaderoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nanna-About The Soul Life of Plants-Gustav Theodor FechnerDocument47 paginiNanna-About The Soul Life of Plants-Gustav Theodor Fechnergabriel brias buendia100% (1)

- 18-My Soul To Take - Amy Sumida (244-322)Document79 pagini18-My Soul To Take - Amy Sumida (244-322)marinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Forward Chaining and Backward Chaining in Ai: Inference EngineDocument18 paginiForward Chaining and Backward Chaining in Ai: Inference EngineSanju ShreeÎncă nu există evaluări

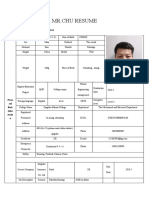

- Mr. Chu ResumeDocument3 paginiMr. Chu Resume楚亚东Încă nu există evaluări

- Barriers To Effective CommunicationDocument15 paginiBarriers To Effective CommunicationpRiNcE DuDhAtRa100% (1)

- Another Three (3) Kinds of Noun!: Collective NounsDocument10 paginiAnother Three (3) Kinds of Noun!: Collective NounsRolan BulandosÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Glass of Vision - Austin FarrarDocument172 paginiThe Glass of Vision - Austin FarrarLola S. Scobey100% (1)

- 2014 FoundationDocument84 pagini2014 FoundationTerry ChoiÎncă nu există evaluări

- MQL4 Book: PrefaceDocument68 paginiMQL4 Book: PrefaceAlif Nur SholikhinÎncă nu există evaluări

- IntroductionPhilosophy12 Q2 Mod5 v4 Freedom of Human Person Version 4Document26 paginiIntroductionPhilosophy12 Q2 Mod5 v4 Freedom of Human Person Version 4Sarah Jane Lugnasin100% (1)