Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Aerobic Exercise and The Placebo Effect - A Controlled Study

Încărcat de

api-3750171Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Aerobic Exercise and The Placebo Effect - A Controlled Study

Încărcat de

api-3750171Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Aerobic Exercise and the Placebo Effect: A Controlled Study

RAYMOND DESHARNAIS, PHD, JEAN JOBIN, PHD, CHARLES COTE, MSC,

LUCIE LEVESQUE, MSC, AND GASTON GODIN, PHD

An experiment was conducted with 48 healthy young adults engaged in a supervised 10-week exercise

program to determine whether a placebo effect is involved within the exercise-psychological enhancement

connection. Based on an expectancy modification procedure, one-half of the subjects were led to believe

that their program was specifically designed to improve psychological well-being (experimental condition)

whereas no such intervention was made with the second half (control condition). Expectations for psycho-

logical benefits and aerobic capacity [VO2max) were measured before and after completion of the program.

Self-esteem, as the indicator of psychological well-being, was measured on four specific occasions: at the

beginning, after the fourth and seventh weeks, and upon completion of the training program. The results

showed similar significant increases in fitness levels in both conditions. Moreover, self-esteem was signifi-

cantly improved over time in the experimental but not in the control condition. These findings provide

evidence to support the notion that exercise may enhance psychological well-being via a strong placebo

effect. Implications of the results with regard to exercise prescription are discussed.

Key words: exercise, placebo effect, self-esteem, psychological enhancement, aerobic capacity.

INTRODUCTION 1940s, it has been common practice in medical re-

search to test new drugs by comparing them with

Despite a growing body of popular and scientific pharmacologically inert placebos under double-

literature supporting the notion that exercise blind conditions. Similar practices have also

enhances psychological well-being, the question of emerged in psychotherapy research, and there has

how this effect operates remains unanswered (1). been growing recognition of the fact that the placebo

Different physiological, biochemical, and psycholog- effect itself is therapeutic (9). Along these lines,

ical hypotheses have been proposed but at the pres- Shapiro and Morris (10) went as far as to claim that

ent time, because of conceptual as well as method- the "placebo effect is an important component and

ological inadequacies, no single theory has received perhaps the entire basis for the existence, popular-

substantial empirical support (2-5). Difficulties in ity, and effectiveness of numerous methods of psy-

reaching a clear consensus around those proposed chotherapy" (p. 369). Initially viewed as an artefact

mechanisms have given additional impetus to the to be controlled for, the placebo effect is now con-

provocative hypothesis that exercise enhances psy- sidered a powerful psychological mechanism in it-

chological well-being via a strong placebo effect (6). self (11). Some authors have even suggested that the

Shapiro and Shapiro (7) define a placebo as "any placebo effect should be maximized in all therapeu-

therapy or component of therapy that is deliberately tic treatment so as to favor patient well-being (12,

used for its nonspecific, psychological, or psycho-

physiological effect, or that is used for its presumed 13), although no consensus has been reached regard-

specific effect but is without specific activity for the ing this position (14).

condition being treated" (p. 372). A placebo effect is The hypothesis that a placebo effect is involved

defined as "the psychological or psychophysiological within the exercise-psychological influence cannot

effect produced by placebos" (7) (p. 372). The placebo be ruled out at the present time, especially as cur-

effect has been the subject of steadily growing inter- rent results from exercise psychology research pro-

est during the last four decades (8). Since the mid- vide some support for the presence of such a mech-

anism. The most widely accepted cognitively based

explanation for the placebo effect is that it is based

on patients' expectations of therapeutic benefit. Ac-

From the Laboratoire des sciences de l'activite physique (R.D., cording to Lundh (9), it is a well-established fact that

C.C., L.L.); Ecole des sciences infirmieres (J.J., G.G.); and Institut medical and psychological treatments may lead to

de Cardiologie de Quebec, Hopital Laval 0.J.), Quebec, Canada. beliefs taking the form of: "this treatment is going to

Address reprint requests to: Raymond Desharnais, PhD, Labor- cure me" and such placebo beliefs, similar to Ban-

atoire des Sciences de l'activite physique, Universite Laval, Ste-

Foy, Quebec GIK 7P4, Canada. dura's definition of outcome expectancies (15), may

Received for publication June 9, 1992; revision received Octo- add to the therapeutic results. In North America,

ber 26, 1992 people's expectations of psychological benefit from

Psychosomatic Medicine 55:149-154 (1993) 149

0033-3174/93/5502-0149S03.00/0

DESHARNAIS et al.

exercise are particularly high because "the popular tally induce an expectancy of improvement. Be-

and professional cultures of the 1980s have led peo- cause placebo and influence "per se" of a treatment

ple to assume that exercise is associated with psy- are widely assumed to be additive (23), the presence

chological health and well-being" (1) (p. 21). More of a placebo effect can thus be inferred when, during

precisely, the psychological benefits of exercise, es- the course of a same treatment, subjects in the

pecially jogging, have been propagandized by the experimental group (i.e., higher expectations) show

popular press and a vast majority of magazine arti- a higher psychological improvement than those in

cles have highlighted its tension and stress-reducing the control group (i.e., lower expectations). Based

effects. Consequently, those who enroll in an aerobic upon an identical research strategy, the present

training program expect to reap as many psycholog- study was designed to assess the influence of in-

ical as biological benefits (16-18). As indicated by duced expectations of improvement from exercise

Folkins and Sime (3), "it is then plausible to hypoth- upon psychological well-being. Specifically, it was

esize that self-selected, motivated volunteers in an hypothesized that exercisers would reap more psy-

experiment may demonstrate improvement in psy- chological benefits when they are led to believe that

chological functioning simply because they are ex- their training program is designed to produce such

pecting such self-enhancement" (p. 386). gains.

From a methodological standpoint, most contem-

porary studies reporting a psychological improve-

ment from exercise cannot eliminate the possibility

that a placebo effect was present to some extent. Use METHODS

of inadequate research strategies is the primary Subjects

cause. In effect, as previously suggested by Morgan

(19), "use of a control group in such experimentation Subjects were 48 healthy young adults (24 men and 24 women)

recruited through the mass media to participate in a study about

should be viewed as a necessary not a sufficient a Health and Fitness Project. Most subjects were students regis-

design consideration. It is equally important, indeed, tered at the local university. The average age of the men and

it is imperative, that a placebo group or sham strat- women was 26.3 ± 5 and 24.7 ± 4 years, respectively. To be

egy be routinely employed" (p. 300). Unfortunately, included in this study, these subjects had to meet the following

most of the studies reviewed have not relied upon criteria: a) consent to train at the university sports center within

the context of a supervised training program three times a week

such a design strategy (1-2). This is especially true in sessions lasting 90 minutes for a duration of 10 consecutive

of earlier studies which were, for the most part, of a weeks; b) acceptance of a random assignment; and, c) limitation

preexperimental nature (3). Recent years have, how- of their weekly training to the prescribed program for the duration

ever, witnessed the emergence of a number of ex- of the study. Subjects were not paid but, as a token of gratitude,

their admission to the training program was free and an individ-

perimental studies that have incorporated the as- ualized report of their physiological and psychological evolution

sessment of subjects' expectations in order to control throughout the program was offered at the end of the study. This

for a potential placebo effect (20-22). This procedure study was approved by the University Human Studies Committee,

constitutes a real methodological improvement over and after an explanation of the purposes and procedures, all

past research, although it is still not adequate for participants gave written informed consent. The consent form

was neutral. All subjects had to sign their consent form before

verifying the presence of a placebo effect. Indeed, to random allocation to either the experimental or the control group.

statistically smooth out any differences in expecta- At this time, the only information available to them was that two

tions will not necessarily eliminate the possibility aerobic programs were offered free of charge. Aside from their

that a placebo effect may exert a similar influence own expectations at the time of signature, no other information

regarding the nature of the possible outcomes from participation

upon the psychological variable in both experimen- was provided.

tal and control conditions.

Double-blind designs, such as those used by phar-

macologists, are indeed the most appropriate to test

the influence of a treatment "per se." However, Training Programs

because of the high expectations now rooted within Of the 48 subjects retained for the study, 24 were randomly

the population, it is practically impossible to verify assigned to the experimental training program (expectancy ma-

the influence "per se" of exercise upon psychological nipulation) and the remaining 24 subjects to the control training

components. An interesting alternative allowing for program while maintaining a balance for sex in each program.

the verification of the eventual occurrence of a Both training programs were identical in length (i.e., 10 weeks),

in the number of weekly training sessions (i.e., three per week),

placebo effect within a treatment was recently pro- and in the number of minutes per session (i.e., 90 minutes). The

posed. This strategy, named "the expectancy modi- format of each session was identical for both conditions; 10

fication procedure" (11), is designed to experimen- minutes warm-up, 70 minutes training session, and 10 minutes

150 Psychosomatic Medicine 55:149-154 (1993)

EXERCISE AND PLACEBO

cool-down. Both programs mostly consisted of group activities were obtained during 4 minutes of sitting quietly on the ergom-

such as jogging through city streets, aerobic dancing, swimming eter prior to stress testing. Then, after 2 minutes of unloaded

pool games, playing soccer, etc. All experimental and control pedaling, the workload was incrementally increased by 20 watts/

training sessions took place in a group under the supervision of minute until exhaustion. A respiratory exchange ratio equal to

the same two leaders, one male the other female, both graduate or greater than 1.1 was the criterion for the achievement of

students in physical activity sciences and specialized in group VOz™*. The average test duration was 9 + 3 minutes. Heart rate

exercise leadership. Experimental subjects trained every week was obtained from ECG recordings at the end of each minute.

on Monday A.M., Wednesday P.M., and Friday A.M. whereas Ventilation, VO2, and VCO2 were recorded every 30 seconds

control participants were scheduled on Monday P.M., Wednesday throughout the test by way of a computerized metabolic cart (P.K.

A.M., and Friday P.M. Moreover, a fourth optional weekly training Morgan).

session was also available on Tuesday P.M. and Thursday A.M. Psychological health and iveJi-being. Self-esteem, defined as

for experimental and control subjects, respectively, who had the degree to which individuals feel positive about themselves

some temporary difficulties with the fixed schedule. At the end (26), was the psychological construct selected to describe overall

of the 10-week programs, four subjects (two in the experimental psychological health and well-being among participants. Indeed,

and two in the control conditions) had dropped out because of self-esteem has been identified as the variable with the greatest

time constraints and incapacity to comply with specific program potential to reflect psychological benefits from exercise (3, 27,

requirements. The remaining 44 subjects (22 men and 22 women) 28). Self-esteem was measured by the Rosenberg Self-Esteem

attended at least 25 of the possible 30 sessions and underwent all Scale (SEI), which is viewed as one of the best instruments for

of the required measurements. evaluating overall self-regard (29). This instrument includes 10

items. For every item, subjects are instructed to indicate on a 4-

point Likert scale the extent to which they agree or disagree.

Possible total score of all items ranges from 10 to 40, higher scores

indicating higher self-esteem. The SEI was administered on four

Expectancy Manipulation specific occasions: at the beginning of the training program, after

According to Lundh (9), beliefs are communicated most per- the fourth and seventh weeks, and upon completion of the train-

suasively if "the [doctor] behaves in such a way that he is ing program. This multiple measurements procedure, carried out

perceived as trustworthy, and an expert in his field. Moreover, over a period of weeks, was preferred to the usual two point (pre-

his belief in the efficacy of the treatment will be communicated post) measurements for its potential to provide a better under-

most effectively if he shows genuine optimism and enthusiasm standing of the process of change in a psychological variable that

with regard to the treatment. Apart from the interest and enthu- may result from participation in a regular exercise program (20)

siasm displayed by the [physician], then, the nature of the verbal For every testing occasion, self-esteem was measured at the end

information is also of great importance" (pp. 136). of the training session.

Exercise leaders were thus selected and trained according to Self-perceptions. In order to verify the effectiveness of the

these recommendations. At the beginning of the 10-week exercise experimental manipulation throughout the entire period, sub-

program, experimental subjects were first informed by exercise jects' self-perceptions were assessed before and after the 10-week

leaders that their training program was designed to improve both exercise program. At the initial meeting, after respective briefing,

aerobic capacity and psychological well-being. Moreover, subjects in each condition filled out a questionnaire in which two

throughout the program, subjects were systematically reminded questions, embedded among the others, asked them to indicate

of these objectives and invited to selectively attend to signs of how effective they expected their training would be for improving

biological and psychological improvement. In the control condi- their: (1) physical fitness and (2) psychological well-being. Both

tion, exercise leaders were instructed to behave in a similarly responses were based upon 7-point scales (e.g., 1 = not at all

enthusiastic manner. However, from the beginning to the end of effective; 7 = very effective). After completion of the 10-week

the program, emphasis was put only on the biological aspect of exercise program, at the end of the last training session, an

the exercise program. At no time during the entire program did adapted version of the same questionnaire was used. This time,

exercise leaders mention psychological benefits as a potential subjects were asked to indicate on a similar 7-point scale how

effect of the exercise program. effective they had found their training for improving their: (1)

physical fitness and (2) psychological well-being. In addition,

subjects were asked to indicate the extent to which they enjoyed

participating and whether they would recommend the program

Variables Measured to a friend. Both responses were arranged on a 7-point scale

ranging from "not at all" to "extremely."

All measures were collected over a 12-week period. Subjects

were not informed of their physiological and psychological scores

during the entire period.

Fitness measurement. Aerobic training is primarily designed to

increase the efficiency of the oxygen transport system. Thus, in RESULTS

order to verify the efficiency of the training programs, fitness

level was assessed in the laboratory by the measurement of Manipulation Checks

maximum oxygen uptake (VO2m0x) 1 week before the first training

session and again upon completion of the program. This procedure The mean scores for the first and second measures

was selected because the level of oxygen consumption at maximal of perceived effectiveness of the program on psycho-

effort represents the most valid measure of this construct (24). As

suggested by Wasserman and colleagues (25), a 1-minute incre- logical well-being and physical fitness are presented

mental test on an electronically braked ergometer (Corival 400, in Table 1. To determine whether the experimental

Quinton, Seattle, WA) was adopted to measure fitness level. The manipulations were successful, a 2 (group) by 2

overall testing procedure was the following: First, resting values (time) repeated-measures analysis of variance (AN-

Psychosomatic Medicine 55:149-154 (1993) 151

DESHARNAIS et al.

TABLE 1. Means and Standard Deviations on Measures of nificant difference among the pre- and postmeasures

Self-Perceptions Before and After the Exercise Program

F(l,42) = 16.09, p < 0.001. However, neither the

Croup Measure Experimental Control main effect for group nor the group-by-time inter-

Prea Post Pre Post action reached statistical significance (p > 0.10).

Psychological well-being M 6.36 5.91 5.40 5.27

These results, therefore, indicate that, after partici-

SD 0.65 0.85 1.43 1.27 pating in the experiment, fitness benefits were sig-

Physical fitness M 6.59 6.50 6.27 6.45 nificant and about the same from one exercise con-

SD 0.66 0.80 1.20 0.67 dition to another.

* Pre, pre-exercise; post, post-exercise.

OVA) was performed for each perception. As ex- Self-esteem

pected, the first analysis revealed that the subjects Table 3 contains the means and standard devia-

assigned to the experimental condition perceived tions for the two groups on the self-esteem scores.

their exercise program as more psychologically ef- In order to examine the evolution of psychological

fective than did those assigned to the control con- health and well-being across the various phases of

dition F(l,42) = 7.02, p < 0.01. However, from the the investigation, a 2 (group) by 4 (time) repeated-

beginning to the end of the training program, this measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was per-

placebo belief tended to decrease in strength F(l,42) formed on self-esteem scores. There was no main

= 3.87, p = 0.06 although this phenomenon was not effect for group (p > 0.10). However, a significant

confined to the experimental group but rather, was main effect for time F(3,126) = 17.67, p < 0.001 and,

found to be common to both conditions as indicated more important, a significant group-by-time inter-

by the nonsignificant group by time interaction action F(3,126) = 5.47, p < 0.01 were reported. As

F(l,42) = 1.34, p > 0.10. Moreover, there was no illustrated in Figure 1, these latter results therefore

significant group by time interaction on measures suggest that the evolution of self-esteem over time

concerned with the perceived effectiveness of the was not the same under each exercise condition.

program on physical fitness, and all other main effect Further repeated-measures analyses of variance on

tests failed to approach conventional levels of statis- the self-esteem scores within each condition re-

tical significance (p > 0.10). Finally, as measured vealed that psychological well-being was signifi-

after program completion, the subjects' level of en- cantly improved over time in the experimental con-

joyment concerning their respective program was dition F(3,63) = 20.3, p < 0.001 but not in the control

similar F(l,42) = 0.25, p > 0.10 and significant for exercise condition F(3,63) = 2.22, p = 0.09, although

the experimental (M = 5.45) and the control (M = this latter result strongly suggests a trend toward

5.54) subjects. Participants in both experimental (M significance. There were no reliable differences

= 6.27) and control (M = 6.41) conditions were also among the groups at the first F(l,42) = 0.15 and at

unanimous F(l,42) = 0.18, p > 0.10 in strongly rec-

ommending their respective training program to

their friends. In summary, experimental and control TABLE 2. Means and Standard Deviations on Measures of

groups differed from each other only on perceived Fitness (ml/kg/min) Before and After the Exercise Program

effectiveness of the program on psychological health Pre-Exercise Post-Exercise

and well-being. It was then concluded from these Time Croup

results that the experimental manipulations had M±SD M ±SD

been successful. Experimental 50.49 ± 11.51 52.49 ± 11.31

Control 48.64 ± 11.17 49.89 ± 11.48

Aerobic Capacity TABLE 3. Means and Standard Deviations on Measures of

Self-Esteem During the Exercise Program

Group means for the VO2max data measured before

Experimental Control

and after the training programs are presented in Croup Time

(weeks)

Table 2. To determine whether the aerobic exercise M + SD M±SD

training led to reliable increases in physical fitness, 1 31.32 ±4.36 31.81 ±4.07

a 2 (group) by 2 (time) repeated-measures analysis 4 33.04 ± 3.92 32.32 ± 3.71

of variance (ANOVA) was conducted on maximum 7 34.68 ± 3.33 32.45 ± 3.69

10 35.23 ± 2.96 33.18 + 4.25

aerobic capacity scores. The analysis yielded a sig-

152 Psychosomatic Medicine 55:149-154 (1993)

EXERCISE AND PLACEBO

36- psychological theory maintains that psychological

improvement gotten from exercise can be attributed

- o EXPERIM

to psychosocial components inherent to the exercise

35- ^S*"'^ program (27, 31). This theory is also unable to ac-

CONTROL yF count for the present findings because the psycho-

2

UJ

UJ 34- social factors maintained were similar and constant

/ throughout both programs. Indeed, the frequency,

SELF-ES

duration, and format of the training sessions were

33- identical for the two programs as were the exercise

leaders and the group context. Confidence in the

effectiveness of our control procedures is strength-

32- ened by the fact that satisfaction measures collected

7 upon program completion were similar for both

groups. Consistent with previous research (11), the

WK-l WK-4 WK-7 WK-10 present findings, therefore, strongly support the

view that the placebo effect is a powerful psycholog-

WEEKS

ical mechanism in itself.

Fig. 1. Self-esteem scores for subjects in the experimental and

control conditions at the 1st, 4th, 7th, and 10th weeks of Although the observed difference in psychological

the exercise program. evolution between the two groups is likely attrib-

utable to a placebo effect, it cannot, however, be

concluded from the present findings that it is the

the fourth week F(l,42) = 0.4. However, group dif- sole mechanism explaining the beneficial influence

ferences reached statistical significance at the sev- of exercise upon psychological well-being. From a

enth week F(l,42) = 4.43, p < 0.05, and there was a methodological viewpoint, a pure placebo effect can

trend that approached statistical significance for the be inferred only when the control group neither

group differences at the 10th week F(l,42) = 3.44, p expects nor shows any specific improvement from a

= 0.07. placebo treatment (9). This was not the case with

the present investigation. Consistent with previous

finding (1, 3), our control subjects were found to

hold high basal expectations for psychological ben-

DISCUSSION efits from their program even without experimental

The results of this investigation provide additional treatment. Moreover, their psychological improve-

support for the notion proposed by Solomon (6) that ment throughout the program approached statistical

a placebo effect may be involved within the exer- significance. Consequently, the hypothesis that

cise-psychological enhancement connection. Ob- mechanisms other than the placebo effect are also

viously, the findings indicated that the experimental involved within the beneficial influence of exercise

subjects, whose expectations for psychological ben- upon psychological well-being cannot be ruled out

efits were strengthened by an expectancy modifi- at the present time.

cation procedure, improved their self-esteem more Regardless of the potential mechanisms that might

during the 10-week exercise program than did the explain the influence "per se" of exercise upon psy-

control subjects. chological well-being, the present findings neverthe-

Although a number of biological and psychologi- less have important implications for exercise pre-

cal mechanisms have been proposed to explain the scription among nonclinical populations. Until now,

exercise and psychological functioning, the ob- the most spectacular psychological benefits of exer-

served difference in self-esteem evolution between cise have been reported primarily for people who

the two exercise groups can hardly be explained by are clinically anxious or depressed whereas incon-

either mechanism. On the one hand, a popular bio- sistent and mitigated results have generally been

logical theory states that psychological improvement found with nonclinical populations (1-5). A possible

from exercise is due to increased aerobic capacity explanation for the discrepancy in results is that

(30). Within the context of the present study how- clinically anxious or depressed persons are particu-

ever, this hypothesis cannot be retained as measures larly receptive to a placebo effect because they gen-

of aerobic capacity at maximal effort reflected sim- erally hold higher expectations for psychological

ilar increases in fitness levels for both experimental benefits (e.g., this treatment is going to cure me)

and control subjects. On the other hand, a prevailing from a specific intervention than nonclinical popu-

Psychosomatic Medicine 55:149-154 (1993) 153

DESHARNAIS et al.

lations (32). In this regard, the findings of the present in psychological interventions (14). This remains an

study indicate that it is possible to induce psycho- ° P e n debate that the present study cannot solve.

logical improvement among nonclinical exercisers

. . . j-r. ,.. , This research was supported by a Bgrant from the

if,r via an expectancy modification procedure, xl they n ,. _.. y;., . , „ , ... .

, . , , , , , , f Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research r Institute

are explicitly led to believe that their program is (6052-4150-2044)

designed to produce such benefits. From an ethical R D a n d GG a r e m e m b e r s of the Research Group

viewpoint, however, no consensus has been reached on Psychosocial Aspects of Health (FCAR-92-ER-

concerning the deliberate use of the placebo effect 0699].

REFERENCES

1. Plante TG, Rodin J: Physical fitness and enhanced psychological health. Curr Psychol Res Rev 9:3-24,1990

2. Doan RE, Scherman A: The therapeutic effect of physical fitness on measures of personality: A literature review. J Counseling Dev

66:28-35, 1987

3. Folkins CH, Sime WE: Physical fitness training and mental health. Am Psychol 36:373-389, 1981

4. Martinsen EW: The role of aerobic exercise in the treatment of depression. Stress Med 3:93-100, 1987

5. Taylor CB, Sallis JF, Needle R: The relation of physical activity and exercise to mental health. Public Health Rep 100:195-202,1985

6. Solomon HA: The Exercise Myth. New York, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1984

7. Shapiro AK, Shapiro E: Patient-provider relationships and the placebo effect. In Matarazzo JD, Weiss SM, Heird JA, Miller NE,

Weiss SM (eds), Behavioral health: A Handbook of Health Enhancement and Disease Prevention. New York, Wiley; 1984, 371-383

8. Lasagna L: The placebo effect. J Allergy Clin Immun 78:161-165,1986

9. Lundh LG: Placebo, beliefs, and health. A cognitive-emotional model. Scand J Psychol 28:128-143,1987

10. Shapiro AK, Morris LA: The placebo effect in medical and psychological therapies. In Garfield SL, Bergin E (eds), Handbook of

Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. New York, Wiley, 1978, 369-410

11. Kirsch I: Response expectancy as a determinant of experience and behavior. Am Psychol 40:1189-1202, 1985

12. Benson H, Epstein MD: The placebo effect. A neglected asset in the care of patients. N Engl J Med 232:1225-1227, 1975

13. Critelli JW, Neumann KF: The placebo. Conceptual analysis of a construct in transition. Am Psychol 39:32-39, 1984

14. Brody H: The lie that heals: The ethics of giving placebos. Ann Internal Med 97:112-118, 1982

15. Bandura A: Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychol Rev 84:191-215,1977

16. Imm PS: Perceived benefits of participants in an employees' aerobic fitness program. Percept Motor Skill 71:753-754,1990

17. Sechrist KR, Walker SN, Pender NJ: Development and psychometric evaluation of the exercise benefits/barriers scale. Res Nurs

Health 10:357-365,1987

18. Wankel LM, Berger BG: The psychological and social benefits of sport and physical activity. J Leisure Res 22:167-182,1990

19. Morgan WP: Psychological benefits of physical activity. In Nagle FJ, Montoye HJ (eds), Exercise in Health and Disease. Springfield,

IL, Charles C Thomas, 1981, 299-314

20. King AC, Taylor CB, Haskell WL, et al.: Influence of regular aerobic exercise on psychological health: A randomized, controlled

trial of healthy middle-aged adults. Health Psychol 8:305-324,1989

21. Moses J, Steptoe A, Mathews A, et al. The effects of exercise training on mental well-being in the normal population: A controlled

trial. ] Psychosom Res 33:47-61, 1989

22. Steptoe A, Edwards S, Moses J, et al.: The effects of exercise training on mood and perceived coping ability in anxious adults from

the general population. J Psychosom Res 33:537-547, 1989

23. Kirsch I: Self-efficacy and expectancy Old wine with new labels. ] Pers Soc Psychol 49:824-830, 1985

24. Astrand PO, Rodahl K: Textbook of Work Physiology, 3rd ed. New York, McGraw Hill, 1986

25. Wasserman K, Hanser JE, Sue DY, et al.: Principles of Exercise Testing and Interpretation. Philadelphia, Lea & Febiger, 1987

26. Gergen KJ: The Concept of Self. New York, Holt, 1971

27. Hughes JR: Psychological aspects of exercise. Prev Med 30:66-78,1984

28. Sonstroem RJ: Exercise and self-esteem. Exer Sport Sci Rev 12:123-155, 1984

29. Wylie RC: The Self-Concept: A Review of Methodological Considerations and Measuring Instruments. Lincoln, University of

Nebraska Press, 1977

30. Stremme SB, Frey H, Harlem OK, et al.: Physical activity and health. Scand J Soc Med 29:9-36, 1982

31. Long B: Aerobic conditioning and stress reduction: Participation or conditioning' Hum Movement Sci 2:171-186, 1983

32. Gallimore RG, Turner JL: Contemporary studies of placebo phenomena. In Jarvik ME (ed), Psychopharmacology in the Practice of

Medicine. New York, Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1977, 254-302

154 Psychosomatic Medicine 55:149-154 (1993)

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Yoga - Patanjali-YogaSutras-Sanskrit-English PDFDocument86 paginiYoga - Patanjali-YogaSutras-Sanskrit-English PDFTantra Path100% (1)

- Ashtanga Yoga As Everyday PracticeDocument17 paginiAshtanga Yoga As Everyday Practiceapi-3750171100% (1)

- Sancrit TermsDocument7 paginiSancrit Termsapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Sanskrit Alphabet PDFDocument2 paginiSanskrit Alphabet PDFavirgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yoga SutrasDocument60 paginiYoga SutrasLeandro MartínezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patch Adams 02Document3 paginiPatch Adams 02api-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Pulmonary Artery Pressure in Ladakhi MenDocument8 paginiPulmonary Artery Pressure in Ladakhi Menapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Spatial and Verbal Memory Test Scores Following YogaDocument4 paginiSpatial and Verbal Memory Test Scores Following Yogaapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Upanishad PDFDocument320 paginiUpanishad PDFSaamratAshokaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rat Hippo Campus and Primary Immune ResponseDocument8 paginiRat Hippo Campus and Primary Immune Responseapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Respiratory Functions in Kalaripayattu PractitionersDocument6 paginiRespiratory Functions in Kalaripayattu Practitionersapi-3750171100% (1)

- Use of Mind-Body Medical TherapiesDocument8 paginiUse of Mind-Body Medical Therapiesapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Rig VedaDocument712 paginiRig Vedaapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Pulmonary Blood Flow Increment and AugmentationDocument8 paginiPulmonary Blood Flow Increment and Augmentationapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Yoga in Cardiac Health (A Review)Document7 paginiYoga in Cardiac Health (A Review)api-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Influence of Yoga On Brain and BehaviourDocument5 paginiInfluence of Yoga On Brain and Behaviourapi-3750171100% (3)

- Modulation of Cardiovascular Response To Exercise by Yoga TrainingDocument5 paginiModulation of Cardiovascular Response To Exercise by Yoga Trainingapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Effect of A One-Month Yoga Training Program OnDocument4 paginiEffect of A One-Month Yoga Training Program Onapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Effect of Yoga Based Lifestyle InterventionDocument7 paginiEffect of Yoga Based Lifestyle Interventionapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Energy Cost and Cardiorespiratory Changes During The Practice of Surya NamaskarDocument7 paginiEnergy Cost and Cardiorespiratory Changes During The Practice of Surya Namaskarapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Yoga As A Therapeutic InterventionDocument17 paginiYoga As A Therapeutic Interventionapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Yoga and DistractibilityDocument11 paginiYoga and Distractibilityapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Yoga As A Therapeutic InterventionDocument17 paginiYoga As A Therapeutic Interventionapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Modulation of Cardiovascular Response To Exercise by Yoga TrainingDocument5 paginiModulation of Cardiovascular Response To Exercise by Yoga Trainingapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- The Effect of Long Term Combined Yoga Practice On The Basal Metabolic RateDocument6 paginiThe Effect of Long Term Combined Yoga Practice On The Basal Metabolic Rateapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- The Application of Yoga To Counselor TrainingDocument16 paginiThe Application of Yoga To Counselor Trainingapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Rapid Stress Reduction and Anxiolysis Among Intensive Yoga ProgramDocument8 paginiRapid Stress Reduction and Anxiolysis Among Intensive Yoga Programapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Modulation of Cardiovascular Response To Exercise by Yoga TrainingDocument5 paginiModulation of Cardiovascular Response To Exercise by Yoga Trainingapi-3750171Încă nu există evaluări

- Physiological Responses To Iyengar YogaDocument17 paginiPhysiological Responses To Iyengar Yogaapi-3718530100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Handbook: Master of Social Work StudiesDocument26 paginiHandbook: Master of Social Work StudiesSukhman ChahalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Human and Health Rights in Relation To Sustainable2Document17 paginiHuman and Health Rights in Relation To Sustainable2ptkabworldÎncă nu există evaluări

- IJHPM - Volume 7 - Issue 12 - Pages 1073-1084 Complex LeadershipDocument12 paginiIJHPM - Volume 7 - Issue 12 - Pages 1073-1084 Complex Leadershipkristina dewiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mini Clinical Examination (Mini-CEX)Document21 paginiMini Clinical Examination (Mini-CEX)Jeffrey Dyer100% (1)

- Alexanders Care of The Patient in Surgery 14th Edition Rothrock Test BankDocument8 paginiAlexanders Care of The Patient in Surgery 14th Edition Rothrock Test BankMarkNorrisajmfkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acute HepatitisDocument14 paginiAcute Hepatitisapi-379370435100% (1)

- Mental Health Issues - ADHD Among ChildrenDocument9 paginiMental Health Issues - ADHD Among ChildrenFelixÎncă nu există evaluări

- Disaster Nursing SAS Session 14Document6 paginiDisaster Nursing SAS Session 14Niceniadas CaraballeÎncă nu există evaluări

- OrphenadrineDocument4 paginiOrphenadrineGermin CesaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Uti StudiesDocument10 paginiUti Studiesapi-302840362Încă nu există evaluări

- Interpretation: LPL - PSC Chandigarh Sector 19-D Booth No:-3, Sector:-19-D ChandigarhDocument5 paginiInterpretation: LPL - PSC Chandigarh Sector 19-D Booth No:-3, Sector:-19-D ChandigarhSanÎncă nu există evaluări

- IGCSE Biology (O610) Workbook: Balanced DietDocument5 paginiIGCSE Biology (O610) Workbook: Balanced DietPatrick Abidra100% (1)

- Antiinflammatorydrugs: Beatriz Monteiro,, Paulo V. SteagallDocument19 paginiAntiinflammatorydrugs: Beatriz Monteiro,, Paulo V. SteagallYohan Oropeza VergaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- NCLEX RN Practice Questions Set 1Document6 paginiNCLEX RN Practice Questions Set 1Jack SheperdÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Architecture and Town Planning-Course-BrochureDocument42 paginiHistory of Architecture and Town Planning-Course-BrochureSabita AmaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Disorder and Diseases of Digestive SystemDocument8 paginiDisorder and Diseases of Digestive SystemCristina AnganganÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vaccination BOON or BANEDocument5 paginiVaccination BOON or BANERushil BhandariÎncă nu există evaluări

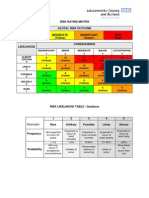

- Example of A NHS Risk Rating MatrixDocument2 paginiExample of A NHS Risk Rating MatrixRochady SetiantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pag-Unawa Sa Mga Panganib NG Sobrang Dosis NG Alkohol: Ano Ang Isang Pamantayang Tagay?Document5 paginiPag-Unawa Sa Mga Panganib NG Sobrang Dosis NG Alkohol: Ano Ang Isang Pamantayang Tagay?Rochelle Bartocillo BasquezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lash Lift Waiver and File SheetDocument2 paginiLash Lift Waiver and File SheettiffyoloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nurses Progress NotesDocument2 paginiNurses Progress Notesvan100% (1)

- Shaikh Sohail Shaikh KaleemDocument1 paginăShaikh Sohail Shaikh KaleemMantra SriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pharmaceuticals Manufacturing - What Do We Know About The Occupational Health and Safety Hazards For Women Working in The Industry PDFDocument61 paginiPharmaceuticals Manufacturing - What Do We Know About The Occupational Health and Safety Hazards For Women Working in The Industry PDFCostas JacovidesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Students Sleep During Classes: The Amount of Time VariesDocument7 paginiStudents Sleep During Classes: The Amount of Time Variesjason_aaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hazard Analysis in The WorkplaceDocument7 paginiHazard Analysis in The WorkplaceUghlahnÎncă nu există evaluări

- الصحة PDFDocument17 paginiالصحة PDFGamal MansourÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trail Mix Cookies IKDocument24 paginiTrail Mix Cookies IKDwi Intan WÎncă nu există evaluări

- Snake Bite SOPDocument5 paginiSnake Bite SOPRaza Muhammad SoomroÎncă nu există evaluări

- JUMPSTART TO SKINNY by Bob Harper: Rule #1Document8 paginiJUMPSTART TO SKINNY by Bob Harper: Rule #1Random House Publishing GroupÎncă nu există evaluări

- Response To States 4.2 Motion in Limine Character of VictimDocument10 paginiResponse To States 4.2 Motion in Limine Character of VictimLaw of Self DefenseÎncă nu există evaluări