Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

U.S. - Korea Economic Relations: A Washington Perspective

Încărcat de

Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

U.S. - Korea Economic Relations: A Washington Perspective

Încărcat de

Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Koreas eas Econo

Koreas Economic Stability and Resilience in Time of Crisis

2010

Koreas Economic Prospects and Challenges

Koreas Economy

The Republic of Korea and the North Paci c Economy: After the Great Panic of 2008 Housing Policy, Mortgage Markets, and Housing Outcomes in Korea Financial Crises and East Asias Financial Cooperation U.S.-Korea Economic Relations: A (Historical) View From Seoul U.S.-Korea Economic Relations: A Washington Perspective The Rocky Road for Modernizing the North Korean Economy How Available are DPRK Statistics?

a publication of the Korea Economic Institute and the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy

Volume 26

CONTENTS

Part I: Overview and Macroeconomic Issues

Koreas Economic Prospects and Challenges Subir Lall . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 Koreas Economic Stability and Resilience in Time of Crisis Lee Jun-kyu . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 The Republic of Korea and the North Pacific Economy: After the Great Panic of 2008 Jeffrey Shafer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Part III: External Issues

U.S.-Korea Economic Relations: A (Historical) View from Seoul Kim Wonkyong . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35 A Washington Perspective Deena Magnall . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Part IV: North Koreas Economic Development and External Relations

The Rocky Road for Modernizing the North Korean Economy Bradley Babson . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45 How Available are DPRK Statistics? Lee Suk . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

Part II: Financial Institutions and Markets

Housing Policy, Mortgage Markets, and Housing Outcomes in Korea Kim Kyung-hwan and Cho Man . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19 Financial Crises and East Asias Financial Cooperation Park Young-joon . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

U.S. KOREA ECONOMIC RELATIONS: A WASHINGTON PERSPECTIVE

By Deena Magnall

At the historic June 2009 Summit, President Barack Obama and President Lee Myung-bak agreed on a shared role for the United States and the Republic of Korea (ROK) in global development and committed to cooperate closely to alleviate the pressing challenges faced by developing nations. In the Summits Joint Vision Statement, the United States and Korea pledged to enhance coordination on peacekeeping, post-conflict stabilization and development assistance . . . [and] also strengthen coordination in multilateral mechanisms aimed at global economic recovery such as the G-20. Development cooperation between the U.S. and Korea presents a new opportunity to collaborate in furthering mutual objectives of poverty reduction and sustainable development in vulnerable, high-priority regions. The U.S. alliance with South Korea is among the most successful and dynamic bilateral relationships in modern history. This new dimension would complement other vital areas of the bilateral alliance and serve to deepen further the growing relationship between the two countries. From Recipient to Donor Koreas own development story is one of swift transformation and nearly unparalleled success. Emerging from a devastated postwar economy, Korea achieved spectacular economic growth and grew to be the 14th-largest economy in the world in less than two generations. In the early 1960s, Koreas economic conditions ranked among the poorest countries in the world. In fact, in 1962 its gross national income (GNI) per capita was less than the average for sub-Saharan Africa. Koreas population at the time was growing rapidly, at a rate of 3 percent per year, with rampant

unemployment throughout the country. During this time, Korea relied heavily on foreign aid, receiving over 6 percent of its GNI in 1960. During the early 1960s, Korea began an aggressive program of economic policy reform. These policies aimed to open up the formerly insular economy to trade, primarily through a strategy of rapid export growth. From 1960 to the mid-1990s, per capita income in Korea grew approximately ten-fold. In fact, Koreas real income per capita growth for any ten-year period during this time outpaced British real per capita income growth during the entire nineteenth century.1 Koreas development success has partly been attributed to its effective use of foreign aid. From 1945 to the late 1990s, Korea received aid totaling nearly $13 billion. Korea has used this success to transform itself from a recipient of aid to a donor country. Today Korea is keen to become a significant contributor in the international development aid community and share its firsthand experience as an aid recipient with other developing countries. In 1996, Korea joined the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and in November 2009 it was unanimously voted to become the newest member of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC). As shown in Figure 1, the volume of Koreas official development assistance (ODA) has increased substantially since the late 1990s.2 Koreas total aid volume amounted to nearly $4.8 billion during the ten-year period from 1998 to 2008. In 2008, Koreas aid reached $802 million, or 0.09 percent of its GNI, an increase of 15 percent from 2007. Furthermore, these figures do not include Korean assistance to the northern half of the peninsulaestimated to be $558

1. Ann Krueger, A Remarkable Prospect: Opportunities and Challenges for the Modern Global Economy (McKenna Lecture, Claremont McKenna College, Claremont, California, 2 May 2006). 2. This excludes Koreas aid in 2005, which saw an unusually large spike due to increased assistance to Iraq and Afghanistan as well as Inter-American Development Bank subscriptions.

EXTERNAL ISSUES

41

million in 2007which is not officially reported to the DAC and, as such, is not recorded officially as ODA.3 The Korean government seeks to continue this trend and has pledged to increase its aid volume to 0.15 percent of its GNI by 2012 and 0.25 percent by 2015the target year set in the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Although Korea has taken significant steps toward achieving its funding targets for 2015 and 2025 (doubling its aid from 2006 to 2009), there are significant challenges in committing to increase aid so sharply in such a short time frame. In 2009, Korea reported an ODA volume of $883 million, which is approximately 0.1 percent of its GNI. This present ODA level is below the average ODA/ GNI percentage of 3 percent of other DAC member nations and the target ratio of the United Nations by 2015 of 0.7 percent. However, these ambitious targets reflect the commitment of the Korean government to become a major donor in the international develop-

ment community and to pay back to the development aid system that played such a large role in its own development process. Innovative initiatives like the Korean air ticket solidarity levy can help address some of these challenges. Under this policy, every passenger departing from Korea pays 1,000 Korean won (roughly $1) to support disease eradication efforts in developing countries, an effort that is expected to raise $20 million annually. In addition to enhancing its aid volume, Korea is also making efforts to reduce its proportion of tied aid in its ODA allocations.4 Koreas ODA has historically been highly tied, with an estimated 98 percent of its aid tied or partially tied in 2006. With its recent entry into the OECD-DAC, however, Korea has pledged to continue making advancements toward reducing its tied aid, as outlined in its Roadmap to Untying. Two days after joining the DAC, the Korean government announced that it plans to untie 75 percent of its aid volume by 2015.

Figure 1: Total ROK ODA Volume, 1998-2008

0.12 800 700 600 500 400 0.05 300 200 317 100 0 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 183 212 265 279 0.04 366 423 455 0.02 0.00 0.07 0.06 0.06 0.06 0.06 752 0.05 696 0.04 0.07 802 0.06 0.10 0.10 0.09 0.08

ODA Total, Net (current prices, USD millions)

ODA/GNI (%)

Source: OECD International Development Statistics Database

3. Development Cooperation of the Republic of Korea, OECD DAC Special Review, Paris, 8 August 2008. 4. Untied aid is dened by the OECD-DAC as ofcial development assistance for which the associated goods and services may be fully and freely procured in substantially all countries.

42

THE KOREA ECONOMIC INSTITUTE

In 2008, Korean net ODA volume comprised 67 percent bilateral aid and 33 percent multilateral aid. The majority of Koreas recent foreign aid has taken the form of bilateral assistance to Asia, representing 52 percent in 2008. Following closely on Chinas November 2009 announcement to double its concessional loan program to Africa (a total of $10 billion over the next three years), Korea has recently increased bilateral assistance to the region through Koreas Initiative for Africas Development and the second Korea-Africa Forum in Seoul, where Korea committed to double its aid to Africa by 2012. In the realm of technical cooperation, Korea also pledged in its Framework for Korea-Africa Development Cooperation 20092012 to accept 5,000 trainees from Africa and to send more than 1,000 Korean volunteers to the continent between 2009 and 2012. Although aid to the African continent is unarguably much needed, Koreas development community may wish to be careful to ensure that its efforts in the region are well directed rather than guided by a desire to keep pace with Chinas activities in the region and to gain greater access to the continents natural resources.

The Korean aid structure directs a significant portion of its ODA volume toward its concessional loan program. In 2008, concessional loans comprised 32 percent of its bilateral ODA, with grants making up 68 percent, a proportion that is much higher than that of most other DAC members. With the exception of three DAC donors, all DAC members have portfolios comprised nearly entirely of grants. In 2008, loans made up 40 percent of Koreas bilateral assistance allocated to the least developed countries (LDCs), while lower middle income countries (LMICs) received 38 percent of its aid in the form of loans. The OECD suggested in its 2008 Special Review of Korea that Korea should be mindful of debt sustainability issues in its development assistance, particularly with respect to the lowest-income countries.5 Korean Development Aid Framework Coordination within the Korean development aid system remains a challenge. Korea currently does not have an overarching legal framework to govern its aid system, nor an overall development strategy to lead its development cooperation activities. Koreas development assistance is managed by two major actors. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MOFAT) heads Koreas grant aid program, which is implemented by the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA). Koreas concessional loan portfolio is administered by the Ministry of Strategy and Finance and is implemented by the Korea Eximbanks Economic Development and Cooperation Fund (EDCF). In addition to these two institutions, 30 other government institutions are involved in implementing the remaining grant aid and technical cooperation programs. As each of the development entities implements separate assistance operations for each recipient country, the Korean aid system creates inefficiencies. The OECD-DAC recommended in its special review that the Korean government create a single entity with sole authority over development cooperation objectives, policy and strategy.6 The OECD argues that

Figure 2: Korea's Bilateral ODA by Region

Other Developing Countries 13% Oceania 1% Europe 2%

Africa 19%

Americas 13%

Asia 52%

Source: OECD International Development Statistics Database

5. The DAC Recommendation on Terms and Conditions of Aid directs that DAC members should endeavor fully to maintain or achieve as soon as possible an average grant element in their ODA commitments of at least 86 percent and that those countries whose ODA/GNI ratios are signicantly below the DAC average will not be considered as having met this terms target. 6. Development Cooperation of the Republic of Korea.

EXTERNAL ISSUES

43

this unified strategy would diminish the inefficiencies and redundant efforts that reduce the coherence and impact of Koreas development policies. A Global Korea In line with its efforts to realize its Global Korea vision, the Korean government is striving to reach international prominence commensurate with its economic standing in the global community. Thanks to its active participation in prior G-20 summits, Korea was chosen to chair the G-20 Summit in Seoul in November 2010, a first for a nonG-8 economy. In addition to its recent accession to the OECD-DAC, Korea will host the Fourth High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness in 2011, where participating countries will gather to assess current progress on global efforts to make aid more effective in reducing poverty and boosting income growth. Korea will also be a participant in the UNs MDGs summit to be held in September 2010. Koreas participation and leadership in these various fora will provide Korea and other emerging donors the opportunity to engage on the global stage in setting agendas and decision-making processes on development cooperation. In particular, Koreas own remarkable development trajectory of transition from recipient to donor country gives Korea valuable insights into how best to achieve global objectives in development assistance. Koreas efforts to increase development coordination with other donor countries will also improve the aid effectiveness and efficiencies of its own development aid system. Another historic milestone was reached on 31 December 2009 with the closing of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) ROK office after nearly 50 years of operations. UNDP played a critical role in rebuilding the postwar Korean economy through the provision of various technical and development assistance programs, which exceeded nearly $100 million since the 1960s. Prior to its closure, the UNDP ROK office worked on many of its programs in tandem with the Korean governments aid cooperation efforts, centering on knowledge transfer of Koreas development experiences to other developing countries. In its place, a new UNDP Policy Center for Global Development Partnership will be established in 2010, focusing on sharing Koreas development experiences with developing countries to promote the UN MDGs.

A New Avenue for U.S.-ROK Cooperation Koreas growing prominence as an emerging donor in the development community offers a promising opportunity for U.S.-ROK engagement. Increased coordination and collaboration between the two countries on global development fronts would facilitate improved efficiencies of aid efforts of both countries and initiate greater progress toward achieving the MDGs. Through such a partnership, both countries could complement their development assistance efforts in a number of areas such as food security, education, agriculture, and global health. Expanding cooperation between U.S. and Korean nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and private voluntary organizations (PVOs) could also improve the delivery of development services and strengthen linkages between these sectors to promote best practices and enhance their technical capacity as development actors. Koreas understanding of the efforts needed to transform a country, not just economically but also in terms of the dramatic cultural and social shifts needed to accommodate such rapid growth and modernization, places the country in a singular position to contribute to improving the effectiveness of the development assistance dialogue. Combining Koreas knowledge with the long experience of the United States as a donor country in development assistance would allow both countries to strategically coordinate efforts and enhance the potential impact of mutual priorities in development aid and global poverty reduction.

Ms. Magnall is an Economic Officer in the Office of Korean Affairs, Bureau of East Asia & Pacific Affairs in the U.S. Department of State. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of State or the U.S. government.

44

THE KOREA ECONOMIC INSTITUTE

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Ohio - 4Document2 paginiOhio - 4Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Oregon - 5Document2 paginiOregon - 5Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Ohio - 7Document2 paginiOhio - 7Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Ohio - 12Document2 paginiOhio - 12Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Ohio - 6Document2 paginiOhio - 6Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Ohio - 10Document2 paginiOhio - 10Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- California - 26Document2 paginiCalifornia - 26Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Top TX-31st Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 paginiTop TX-31st Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Tennessee - 5Document2 paginiTennessee - 5Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Pennsylvania - 5Document2 paginiPennsylvania - 5Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Pennsylvania - 5Document2 paginiPennsylvania - 5Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Top TX-30th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 paginiTop TX-30th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Ohio - 1Document2 paginiOhio - 1Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Florida - 25Document2 paginiFlorida - 25Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Indiana - 8Document2 paginiIndiana - 8Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Washington - 4Document2 paginiWashington - 4Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- Washington - 8Document2 paginiWashington - 8Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Connecticut - 1Document2 paginiConnecticut - 1Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Missouri - 1Document2 paginiMissouri - 1Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Top CA-34th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 paginiTop CA-34th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Maryland - 6Document2 paginiMaryland - 6Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Texas - 35 - UpdatedDocument2 paginiTexas - 35 - UpdatedKorea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Top TX-31st Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 paginiTop TX-31st Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Tennessee - 7Document2 paginiTennessee - 7Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Top CA-13th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 paginiTop CA-13th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Top TX-17th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 paginiTop TX-17th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Top TX-19th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 paginiTop TX-19th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Top FL-17th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Document2 paginiTop FL-17th Export of Goods To Korea in 2016Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (120)

- Oregon - 4Document2 paginiOregon - 4Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- Georgia - 9Document2 paginiGeorgia - 9Korea Economic Institute of America (KEI)Încă nu există evaluări

- The Transformationof Japans Foreign Aid PolicyDocument7 paginiThe Transformationof Japans Foreign Aid PolicyVeni YulianingsihÎncă nu există evaluări

- III. Audit Program On Distribution and Entitlement On COVID-19 FundsDocument7 paginiIII. Audit Program On Distribution and Entitlement On COVID-19 FundsKathleenÎncă nu există evaluări

- South Sudan Gender AnalysisDocument68 paginiSouth Sudan Gender AnalysisOxfamÎncă nu există evaluări

- 21mmsmeklaaug034 (FV2)Document74 pagini21mmsmeklaaug034 (FV2)Kadondi AgathaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pakistan Donor DirectoryDocument213 paginiPakistan Donor DirectoryIbn e Insaan87% (53)

- Cultural ImperialismDocument23 paginiCultural ImperialismscarletinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Middle Kingdom's Lighter Touch: Chinese Soft Power in AfricaDocument27 paginiThe Middle Kingdom's Lighter Touch: Chinese Soft Power in AfricacjpetallidesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Global Monitoring Report 2012Document404 paginiGlobal Monitoring Report 2012Sanity FairÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abaleta - Learning Journal CourseworkDocument4 paginiAbaleta - Learning Journal CourseworkJhenjhen PotpotÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- OCHA Deployment - Final 3 May For CirculationDocument8 paginiOCHA Deployment - Final 3 May For CirculationMichael SmithÎncă nu există evaluări

- National Security Strategy 199301 PDFDocument26 paginiNational Security Strategy 199301 PDFpuupuupuuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foreign Aid in UgDocument6 paginiForeign Aid in UgIbrahim FazilÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Impact of Economic Development Programs and The Potential of Business Incubators in HaitiDocument54 paginiThe Impact of Economic Development Programs and The Potential of Business Incubators in HaitiDrew Mohoric100% (1)

- US-Aid To PakistanDocument12 paginiUS-Aid To PakistanMuhammad FaridÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2013-2018 U. S. Foreign - Aid - v122Document40 pagini2013-2018 U. S. Foreign - Aid - v122Daniel MorrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Final Mondernization TheoryDocument15 paginiFinal Mondernization TheoryAdrian De Goal Getter100% (1)

- Clauses - MUNDocument18 paginiClauses - MUNKanishka SINGHÎncă nu există evaluări

- Achieving The Millennium Developmeny Goals in The Asia-Pacific Region - The Role of International AssistanceDocument16 paginiAchieving The Millennium Developmeny Goals in The Asia-Pacific Region - The Role of International AssistanceroblagrÎncă nu există evaluări

- Maastricht University Sbe Master ThesisDocument8 paginiMaastricht University Sbe Master Thesisnikkismithmilwaukee100% (1)

- Unit 1 Reforms in Financial SystemDocument41 paginiUnit 1 Reforms in Financial SystemHasrat AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Developmental Legal Advocacy in Rural ASEAN-JWDDocument14 paginiDevelopmental Legal Advocacy in Rural ASEAN-JWDJane GaliciaÎncă nu există evaluări

- B049. ICA 3. Development EconomicsDocument3 paginiB049. ICA 3. Development EconomicsMahiyal Kaur BediÎncă nu există evaluări

- School DRRM-CCAM Action Plan For S.Y. 2018-2019Document5 paginiSchool DRRM-CCAM Action Plan For S.Y. 2018-2019Mila Chan Nortez CastañedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Role of Financial Institutions in Agricultural DEVELOPMENT (1990-2014) A Case Study of Nigeria Agricultural Cooperative and Bank of IndustryDocument58 paginiThe Role of Financial Institutions in Agricultural DEVELOPMENT (1990-2014) A Case Study of Nigeria Agricultural Cooperative and Bank of IndustryAgboola JosephÎncă nu există evaluări

- Just Waiting To Die? Cambodian Refugees in ThailandDocument41 paginiJust Waiting To Die? Cambodian Refugees in ThailandOxfamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pandemic MillionairesDocument15 paginiPandemic MillionairesSayuri GoyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Studying Abroad On A Budget - Odyssey ScholarsDocument7 paginiStudying Abroad On A Budget - Odyssey ScholarsSDA UChicagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Instructions For Authors Permissions andDocument22 paginiInstructions For Authors Permissions andguzel nsmÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Construction Industry in Developing CountriesDocument577 paginiThe Construction Industry in Developing CountriesYoseph Birru100% (1)

- Chapter - 9: General Financial Rules 2017Document40 paginiChapter - 9: General Financial Rules 2017PatrickÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Pursuit of Happyness: The Life Story That Inspired the Major Motion PictureDe la EverandThe Pursuit of Happyness: The Life Story That Inspired the Major Motion PictureÎncă nu există evaluări

- Son of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable ChoicesDe la EverandSon of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable ChoicesEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (497)

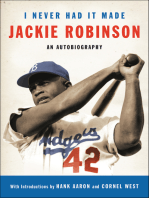

- I Never Had It Made: An AutobiographyDe la EverandI Never Had It Made: An AutobiographyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (38)

- Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldDe la EverandPrisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (1145)

- Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement,De la EverandBound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement,Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (69)

- Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentDe la EverandAge of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (6)

- The Devil You Know: A Black Power ManifestoDe la EverandThe Devil You Know: A Black Power ManifestoEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (10)

- How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyDe la EverandHow States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (7)