Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Tehnici de Argumentare

Încărcat de

kosmotrotter7137Descriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Tehnici de Argumentare

Încărcat de

kosmotrotter7137Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

I.

Argumentum ad Hominem (abusive and circumstantial): the fallacy of attacking the character or circumstances of an individual who is advancing a statement or an argument instead of trying to disprove the truth of the statement or the soundness of the argument. Often the argument is characterized simply as a personal attack. A. The personal attack is also often termed an "ad personemargument": the statement or argument at issue is dropped from consideration or is ignored, and the locutor's character or circumstances are used to influence opinion. B. The fallacy draws its appeal from the technique of "getting personal." The assumption is that what the locutor is saying is entirely or partially dictated by his character or special circumstances and so should be disregarded. II. The "tu quoque" or charging the locutor with "being just like the person" the locutor speaking about, is a narrower variety of this fallacy. In other words, rather than trying to disprove a remark about someone's character or circumstances, one accuses the locutor of having the same character or circumstances. A. In cross examination or in debate, the point is often expressed as "My point might be bad, but yours is worse." B. If the subject includes an assessment of behavior, the point can be put "So I do x [some specific action], but you do too." III. Since the circumstantial variety of the ad hominem can be regarded as a special case of the abusive, the distinction between the abusive and the circumstantial is often ignored. Informal Structure of ad Hominem Person L says argument A. Person L's circumstance or character is not satisfactory. Argument A is not a good argument.

IV.Examples of the ad hominem: A. A prosecutor asks the judge to not admit the testimony of a burglar because burglars are not trustworthy.

B. Francis Bacon's philosophy should be dismissed since Bacon was removed from his chancellorship for dishonesty.

C. Prof. Smith says to Prof. White, "You are much too hard on your students," and Prof. White replies, "But certainly you are not the one to say so. Just last week I heard several of your students complaining."

D. I can't see that we should listen to Governor Smith's proposal to increase the sales tax on automobiles. He has spent the last twenty years in state government and is hardly an unbiased source. V. Uses of ad hominem considerations:

A. When examining literary or philosophical works, looking at the author's character or circumstances can sometimes provide insight into that person's ideas. In other words, ad hominemconsiderations can show motives and can sometimes provide explanation. However, these considerations do not demonstrate the truth or falsity of the ideas. B. The character of a person is often relevant in consideration of the sincerity of views being offered and so is often relevant to pragmatic decision-making. VI. Self-reference and ad hominem: A. If a philosopher presents a "naturalistic view of knowledge," arguing that all knowledge is a function of the adjustment of an organism to its environment and at the same time pleads that his own knowledge is an exception to this generalization, then the ad hominem fallacy would occur. B. If William James were to claim that all philosophers were either tender-minded or tough-minded except for him with respect to his own variety of pragmatism, then an ad hominem appeal should not be ruled inadmissible against James.. I. Argumentum ad Misericordiam (argument from pity or misery) the fallacy committed when pity or a related emotion such as sympathy or compassion is appealed to for the sake of getting a conclusion accepted. A. Hence, assent or dissent to a statement or an argument is sought on the basis of an irrelevant appeal to pity. In other words, pity, or the related emotion is not the subject or the conclusion of the argument. B. The informal structure of the ad misericordiam usually is something like this: Person L argues statement p or argument A. L deserves pity because of circumstance y. Circumstance y is irrelevant to p or A. Statement p is true or argument A is good. II. Some typical ad misericordiam fallacy examples follow.

Georgia Banker Bert Lance should be excused from conflict of interest divestiture problems, former President Jimmy Carter asserted, because Lance's promise to sell his stock so that he can serve his government has depressed its market value.

Oh, Officer, There's no reason to give me a traffic ticket for going too fast because I was just on my way to the hospital to see my wife who is in serious condition to tell her I just lost my job and the car will be repossessed.

Members of Congress can surely see in their hearts that they need to vote in favor of passage of the Gun Bill allowing concealed weapons because their constituents who lobby for liberalizing firearms will be greatly saddened if they do not do so.

Public Schools, K through 12, need to have much easier exams for students because teachers don't fully realize the extent of the emotional repercussions of the sorrow and depression of the many students who could score much better on easier exams.

Richard P. Feynman, the Nobel Prize winning physicist, has been misunderstood almost all of his life. Since World War II, he came close twice to having a mental breakdown--first with the death of his wife and second with the explosion of the atomic bomb. I think that the Journal of Science should publish some of his later theoretical work out of our kind regard for his memory and from the interest of human concern for his difficult life.

III. Related emotions include sympathy, love, regard, mercy, condolence, and compassion. Occasionally, an occurrence of a fallacy can be correctly analyzed as either the ad populum or the ad misericordiamfallacy since these fallacies overlap in their appeal. IV. Non-fallacious uses of the ad misericordiam include arguments where the appeal to pity or a related emotion is the subject of the argument or is a pertinent or germane reason for acceptance of the conclusion. A. Relief arguments are relevant to the problems raised by a disaster caused by a tidal wave and cholera outbreak in India. B. If we have the choice of buying a newspaper from a blind news vendor, ad misericordiam considerations are not necessarily irrelevant. The essential question is whether the pity or compassion is relevant to the situation at hand and is being appealed to exclusively or excessively for the acceptance of the conclusion. C. In Voltaire's Candide, examples of misery are used time and time again to falsify Leibniz's (Pangloss') assertion that this is the best of all possible worlds. The evidence would be relevant to the argument being adduced.

Argumentum ad consequentiam (The Argument To Consequence) Appeal to consequences, also known as argumentum ad consequentiam (Latin for "argument to the consequences"), is an argument that concludes a premise (typically a belief) to be either true or false based on whether the premise leads to desirable or undesirable consequences. This is based on an appeal to emotion and is a form of logical fallacy, since the desirability of a consequence does not address the truth value of the premise. Moreover, in categorizing consequences as either desirable or undesirable, such arguments inherently contain subjective points of view. Example: Positive FormIf P, then Q will occur.Q is desirable.Therefore, P is true Negative FormIf P, then Q will occur.Q is undesirable.Therefore, P is false

Argumentum ad hominem (The Argument To The Person) An ad hominem (Latin: "to the man"), short for argumentum ad hominem, is an attempt to link the validity of a premise to a characteristic or belief of the person advocating the premise. The ad hominem

is a classic logical fallacy, but it is not always fallacious; in some instances, questions of personal conduct, character, motives, etc., are legitimate and relevant to the issue. Example: "You can't believe Jack when he says the proposed policy would help the economy. He doesn't even have a job." Common Misconception: Gratuitous verbal abuse or "name-calling" itself is not an ad hominem or a logical fallacy. Argumentum ad misericordiam (The Argument To Pity) An appeal to pity (also called argumentum ad misericordiam) is a fallacy in which someone tries to win support for an argument or idea by exploiting his or her opponent's feelings of pity or guilt. The appeal to pity is a specific kind of appeal to emotion. Example: "What do you mean I can't get a job here? All my friends work here! This is unfair! You're going to make me cry. How could you do this to me?" Argumentum ad populum (The Argument To The Masses) In logic, an argumentum ad populum (Latin: "appeal to the people") is a fallacious argument that concludes a proposition to be true because many or all people believe it; it alleges: "If many believe so, it is so." Example: "Nine out of ten of my constituents oppose the bill, therefore it is a bad idea." "Watch Show X - the #1 watched show on television!"

Argumentum e contrario (The Argument From/To The Opposition) In logic, an argumentum e contrario (Latin: "appeal from the contrary" or "argument based on the contrary") denotes any proposition that is argued to be correct because it is not proven by a certain case. It the opposite of the analogy. Arguments "e contrario" are often used in the legal system, as a way to solve problems not currently covered by a certain system of laws. Although it might be used as a logical fallacy, arguments "e contrario" are not by definition fallacies. Example: "Section 1 of the X-Law says that green cars need to have blue tires. As such, red cars don't have to have blue tires."

Here the argument is based on the fact that red cars are not green cars and as such 123 of the X-Law cannot be applied to them. This requires the law to be interpreted to determine which solution would have been desired if the lawmaker had considered red cars.

In this case it's probably safe to assume that they only wanted to regulate green cars and not regulate cars of other colors.

Un argument ad hominem, cunoscut i ca argumentum ad hominem (latin: "argument la persoan", "argument mpotriva omului") const n a rspunde la un argument sau la o afirmaie despre un fapt prin atac la persoana care a fcut afirmaia, n loc s se adreseze la subiectul argumentului sau s produc o dovad contra afirmaiei. Aceast eroare logic se refer la criticile sau atacul la persoana care face afirmaiile i prin care se ncearc discreditarea argumentului. Un alt subtip comun al acestui argument greit este argumentul ad hominem circumstanial (argumentum ad hominem circumstantiae), un atac care este bazat pe circumstanele sau pe situaia interlocutorului; la fel argumentul "tu quoeque" (i tu) a crui obiecie la argument const n caracterizarea acestuia ca fiind vinovat de acelai lucru mpotriva cruia argumenteaz. Argumentele ad hominem sunt ntodeauna invalide n logica silogistic, date fiind valoarea de adevr a premiselor i validitatea inferenei logice ca independente de persoana care face inferena. Oricum, argumentele ad hominem sunt rar prezentate ca silogisme formale, iar forma lor ine de domeniul logicii informale i al teoriei evidenei. Pe de alt parte, teoria evidenei depinde n mare msur de evaluarea credibilitii martorilor, inclusiv a mrturiilor date de martori oculari sau de experi. Dovezi c un martor ocular propus nu este de ncredere, sau are motive s mint, sau c martorul expert propus nu are cunotinele necesare pot juca un rol decisiv n emiterea de judeci. Argumentul ad hominem este opusul apelului la autoritate n care interlocutorul i bazeaz valoarea de adevr a unei afirmaii pe autoritate, pe cunotinele sau pe poziia persoanei care a fcut inial afirmaiile. De aceea, chiar dac argumentul ad hominem poate face o afirmaie mai puin convingtoare, artnd c persoana care face afirmaia nu are autoritatea, cunotinele sau poziia de a face acele afirmaii sau a fcut afirmaii eronate n trecut despre subiecte similare, totui, nu poate furniza un contraargument infailibil. [modific]Ad hominem ca eroare logic formal Un argument ad hominem eronat are urmtoare form de baz: O persoan A face afirmaia X Este ceva criticabil la adresa persoanei A Prin urmare afirmaia X este fals Argumentul ad hominem este eroarea logic cea mai cunoscut i de obicei menionat n introducerile la manualele de logic i n manualele de gndire critic. Att eroarea logic n sine ct i acuzaia de a fi comis-o sunt frecvent fluturate n discursuri. Ca tehnic n retoric este foarte puternic i des folosit datorit nclinaiei naturale a creierului uman de a recunoate abloane. Exemplu: Nazitii au adoptat un plan de eugenie. Nazitii au fost ri. Prin urmare, eugenia este rea. Prima premis este numit "afirmaia faptic" i este punctul pivot al discuiei. Controversa este numit "afirmaia inferenial" i prezint procesul gndirii. Exist dou tipuri de afirmaii infereniale, explicite i implicite. Eroarea logic nu repezint o form valid de raionament deoarece chiar i n situaia n care se accept ambele co-premise, acest lucru nu garanteaz valoarea de adevr a controversei. Poate fi gndit i c argumentul are o co-premis ne-declarat.

Fallacies of Relevance

Fallacies of relevance are fallacies which are due to a lack of a relevant logical connection between premise and conclusion.

Appeal to force

An appeal to force (Lat: argumentum ad baculum) is an argument which uses a threat of violence or force as a justification for the conclusion. An appeal to force argument follows the form: If person A does not accept P, then Q Q is a threat of force Therefore P is true

For example: "If you do not pay me $30 I will break your leg. Therefore you owe me $30." It is fallacious because no amount of force can change the truth or falsity of the initial proposition.

Appeal to pity

Also called emotional appeal, (Lat: ad misericordiam) this fallacy is characterized by a use of emotion as a justification for the conclusion. An appeal to pity follows the form: Person A argues P Person B agrees P, but adds X, where X is an emotional argument unconnected to P For example: "Yes, officer, I realize I was speeding, but you shouldn't give me a ticket because I was racing to see my wife who is in thehospital." While this argument uses an emotional appeal to convince the officer not to hand out a citation, there is no logical connection between the premise ("you shouldn't give me a ticket") and the conclusion ("I was racing to see my wife"). Appeals to pity are very commonly seen in business. A factory manager may make the following argument: "our factory's overheads are too high, and we cannot maintain our business if we continue here. Therefore we should relocate to an area where labour is cheaper." An appeal to pity would be of the following type: "but our workers have bills to pay, families to support, we cannot fire them." That statement may be true, but is fallacious because it is not relevant to the manager's argument.

Appeal to Consequences

An appeal to consequences is an attempt to motivate belief with an appeal either to the good consequences of believing or the bad consequences of disbelieving. This may or may not involve an appeal to force. Such arguments are clearly fallacious. There is no guarantee, or even likelihood, that the world is the way that it is best for us for it to be. Belief that the world is the way that it is best for us for it to be, absent other evidence, is therefore just as likely to be false as true. The following is an example: If you believe in evolution, then you'll be miserable, thinking that life is meaningless Therefore, evolution is false This argument commits the appeal to consequences fallacy because it provides no evidence for its conclusion; all it does is appeal to the consequences of believing in evolution. Evolution is not disproven solely because it leads to bad consequences for those who believe in it. The following is a similar example: If you believe in evolution, then you'll be more respected in academic circles Therefore, evolution is true This makes an appeal to the positive consequences of believing in evolution, without actually providing any proof of evolution itself. Just because belief in evolution makes you more respected by liberal professors, this does not mean that evolution is correct.

Argumentum ad hominem

Main Article: Ad hominem Ad hominem arguments (Lat: "argument directed toward the man") fall into two forms: ad hominem abusive and ad hominem tu quoque(circumstantial).

Ad hominem abusive

An ad hominem is an argument which tries to disprove another argument by attacking the person who made it, rather than by focusing on the actual logical reasoning. The goal of an ad hominem argument is usually to take focus off of the actual argument by calling attention to a flaw of the person making it. This form of argument follows the form:

Person A argues that P Person A is Q Q is some derogatory description not related to the argument at hand Therefore P is false

Ad hominem tu quoque

A tu quoque argument (Lat: "you're another") is one which argues that, because someone does that which they are arguing against, that person must be wrong. This form of argument follows the form: Person A argues that P should not happen Person A does P Therefore Person A's argument is incorrect For example: "You can't tell me not to eat cheeseburgers, I just saw you eating one last week!" Another common example is often found in business: "why are you punishing me for dumping waste in the river? My opponent does the exact same thing and you don't punish him!" In this case, dumping waste into the river is wrong (and illegal) regardless of how it is enforced for any other company.

2. Formal fallacies in disjunctive syllogism This arises from the use of the disjunctive syllogism. a. Alternatives not mutually exclusive This arises when the use of one of the alternatives does not preclude the use of the other. Example: He is either a non-believer or an atheist; He is not an atheist; .. He is a non-believer. b. Possibilities not exhaustive When the possibilities used in the predicate of the disjunctive major premise are not exhaustive, this fallacy arises. Example: Senator A is either a Nacionalista or a Liberal; Senator A is not a Nacionalista; ..Senator A is Liberal. Argumentum ex concession This is an argument from a previous admission. This arises when the disputant ignores the real question and asserts that his contention is valid because his opponent has previously admitted it to be so.

(6)Argumentum ex concessio is an argument from a previous admission. This fallacy arises when the disputant ignores the real question and asserts that his contention is valid because his opponent has previously admitted it to be so. Example: (c)Complex question involves a question that presumes another hidden question that makes it complex. Example: Question: Have you stopped visiting my wife? Answer: Yes or No. If the respondent answers the question with yes, then a conclusion can be presumed that, The respondent had visited my wife, and now he stops. And if the respondent answers the question with no, then a conclusion can be presumed that, The respondent has been visiting my wife up to the present. (d)Non sequitor (1)Simple non sequitor arises when the arguer draws a conclusion from a premise, without having a valid connection between the assumed or known truth in the premise and the alleged truth in the conclusion. Example: John is the most behave student in the class; therefore, he should be given the most tasks.

(2)False cause post hoc, ergo propter hoc occurs when there is confusion in inferring cause-effect correlations. Example: Yesterday, I received a letter obliging me to write the same for fifty pieces. Days had passed and I failed to do so. I met an accident. Therefore, this letter must be mysterious.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Edible Forest Gardens Volume 2 UNEDITEDDocument668 paginiEdible Forest Gardens Volume 2 UNEDITEDkosmotrotter7137100% (8)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Ins Analysis Bio ActivityDocument11 paginiIns Analysis Bio Activitykosmotrotter7137Încă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Anne Hooper - Lovers Weekend GuideDocument122 paginiAnne Hooper - Lovers Weekend Guidemalleshpage225552% (23)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (894)

- Barbara E. Hort (1996) Unholy Hungers (ISBN 1570621810)Document150 paginiBarbara E. Hort (1996) Unholy Hungers (ISBN 1570621810)kosmotrotter7137100% (3)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Dealing With Frustration and AngerDocument120 paginiDealing With Frustration and AngerShubham AgarwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Fallacies Identification & Description WorksheetDocument5 paginiFallacies Identification & Description WorksheetmikeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Types of Logical FallaciesDocument5 paginiTypes of Logical FallaciesEmÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Stem - Written Close Analysis FormatDocument5 paginiStem - Written Close Analysis FormatJealf Zenia Laborada CastroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Procedural FallaciesDocument10 paginiProcedural FallaciesAlyssa Lorraine PeraltaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- Analitycal Ability 01Document15 paginiAnalitycal Ability 01Morium ZafarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mediate InferenceDocument39 paginiMediate Inferencemish berns50% (2)

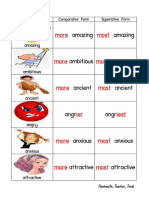

- More Most: Amazing AmazingDocument47 paginiMore Most: Amazing AmazingHeidy Mariana RIOS BERNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Arguments and Necessary and Sufficient ConditionsDocument20 paginiArguments and Necessary and Sufficient ConditionsdaniellestfuÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Fallacies ListDocument18 paginiFallacies ListDaft_AzureÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Comparison of AdjectivesDocument9 paginiComparison of AdjectivesdatomarsaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- 2 The Anatomy ArgumentsDocument22 pagini2 The Anatomy ArgumentsMohammed SalehÎncă nu există evaluări

- Figurative Language What Is ItDocument2 paginiFigurative Language What Is ItAhmed Abd El-hameed Ali75% (4)

- Test The Validity of This ArgumentDocument18 paginiTest The Validity of This ArgumentGayatri Ramesh SutarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Logical Fallacies ExplainedDocument17 paginiLogical Fallacies ExplainedERICA EYUNICE VERGARAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adjetivos Comparativos y SuperlativosDocument3 paginiAdjetivos Comparativos y SuperlativosjoseÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Figures of SpeechDocument25 paginiFigures of Speechrshmmshr7100% (20)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- Fallacy: Group 4 Jaz Moral Jazztine Nevalga Samantha Salayon Danna Rose VergaraDocument12 paginiFallacy: Group 4 Jaz Moral Jazztine Nevalga Samantha Salayon Danna Rose VergaraRazzel VergaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Standard Form, Mood, and Figure of Categorical SyllogismsDocument5 paginiStandard Form, Mood, and Figure of Categorical SyllogismsHamid IlyasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conductive ReasoningDocument6 paginiConductive Reasoningvincent dela cruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Typical Fallacies in ReasoningDocument16 paginiTypical Fallacies in ReasoningBhanu AryalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fallacies of RelevanceDocument20 paginiFallacies of RelevanceVõ Thị Diễm QuỳnhÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2 +Agrippa's+Trilemma+ (Readable)Document56 pagini2 +Agrippa's+Trilemma+ (Readable)Alabani DanielÎncă nu există evaluări

- Formal and Non Formal FallaciesDocument36 paginiFormal and Non Formal Fallaciesexolweareoneexo61Încă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Comparative and Superlative Adjectives ListDocument11 paginiComparative and Superlative Adjectives ListJeel MistryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Logical Reasoning MCQDocument42 paginiLogical Reasoning MCQkavi.kutty13Încă nu există evaluări

- Logical Fallacies I Fallacies of Relevance: Mcgraw-Hill/Irwin © 2013 Mcgraw-Hill Companies. All Rights ReservedDocument17 paginiLogical Fallacies I Fallacies of Relevance: Mcgraw-Hill/Irwin © 2013 Mcgraw-Hill Companies. All Rights ReservedMahnoor KamranÎncă nu există evaluări

- "Bandwagon Approach" (Sometimes Called Appeal To Popularity)Document1 pagină"Bandwagon Approach" (Sometimes Called Appeal To Popularity)ivyjoykristi llegosburiÎncă nu există evaluări

- SLM GM11 Quarter2 Week9Document32 paginiSLM GM11 Quarter2 Week9Vilma PuebloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Types of Logical Fallacies ExplainedDocument2 paginiTypes of Logical Fallacies ExplainedReynald Lentija TorresÎncă nu există evaluări

- Making Sense of Arguments: Chapter ObjectivesDocument12 paginiMaking Sense of Arguments: Chapter ObjectivesOVS TutoringÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)