Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

EU Law Free MVT Critique

Încărcat de

WebIcy AmaniTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

EU Law Free MVT Critique

Încărcat de

WebIcy AmaniDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Luropa lnsLlLuLe

MlLchell Worklng aper Serles

Lmp|oyment k|ghts, Iree Movement

Under the LC 1reaty and the

Serv|ces D|rect|ve

CaLherlne 8arnard

3/2008

1

Lmployment Rights, Iree Movement under the LC 1reaty and the Services Directive

Catberive arvara

1be var/et acce.. te.t aaotea b, tbe Covrt of ]v.tice iv tbe fieta of free vorevevt of er.ov. ba. tovg tbreatevea to

vvaervive vatiovat evto,vevt tar. 1be aeci.iov. iv Viking ava Laal brovgbt tbe.e fear. ivto .bar focv.. !bev tbe

errice. Directire ra. beivg vegotiatea, tbe traae vviov. vaae .vbvi..iov. to tbe vroeav Partiavevt ov tbe ra,. of

rivgfevcivg vatiovat tabovr tar frov tbe tevtacte. of tbe errice. Directire. v vav, ra,. tbe, rere .vcce..fvt. orerer,

tbeir rictor, va, rett be ,rrbic: tbe C 1reat, covtivve. to at, ava, a. Viking ava Laal .bor, it va, rett be

aifficvtt iv ractice to ;v.tif, vatiovat evto,vevt tar. iv tbe .trict terv. reqvirea b, tbe C].

J. Introduction

1he protection o the Luropean social model rom the challenges posed by the creation o a single

market has been a long-running issue acing the LU. Jacques Delors, the Commission President at the

time o the launch o the 1992 programme, struck a bargain with the L1UC where he assured trade

unions that the internal market would be accompanied by a rat o workplace regulations combined

with a social dialogue, an ambitious programme to achiee equality between men and women, a social

policy programme, the strengthening o basic social rights and the creation o a clearly deined social

dimension`.

1

\ith Delors` departure, this commitment has come under eer greater strain due to the

act that traders, migrant workers and serice proiders hae increasingly used the 1reaty proisions on

the our reedoms to challenge national employment laws. \here these challenges hae proed

successul, and vatiovat employment laws hae been ound incompatible with LC Law, this has not

been matched by re-regulation at Community leel. 1his is due in part to the Member States` increasing

reluctance to agree to Community legislation in the social ield, despite the eer expanding competence

that the LC now enjoys in the social ield.

1he Serices Directie 2006,123 brought these debates into sharp - and highly political -

ocus. Many in the union moement argued that, by acilitating ree moement, the Directie gae a

green light to social dumping`, with urther erosion o the content and enorcement o national

employment laws. 1his, they argued undermined the ,ill-deined, Luropean social model. 1he aim o

this paper is to consider the challenges to national protection o employment rights posed by the LC

1reaty rules on ree moement, challenges gien signiicant prominence due to the decisions in 1i/ivg

2

1rinity College, Cambridge, Reader in LU Law, Jean Monnet Chair in LU Law. I am particularly grateul to Claes-Mikael

Jonsson or his generous assistance with this paper. 1his paper will appear in M.Ronnmar ,ed.,, ^atiovat vav.triat Retatiov. r.

| vav.triat Retatiov., ,Kluwer, 2008, orthcoming,.

1

W. Kowalsky, The Services Directive: the Legislative process clears the first hurdle (2006) 12 Transfer 231, 247.

2

Case C-438/05 International Transport Workers Federation v Viking Line ABP [2007] ECR I-000.

2

and arat

3

. It is against this background that I will consider the background to and the eect o the

Serices Directie as it relates to employment law matters.

2. 1he Interaction between the LC 1reaty and National Lmployment Laws

.. vtroavctiov

1he draters o the original 1reaty o Rome ocused their attention primarily on the achieement o the

our reedoms - o goods, persons, serices and capital. lighly inluenced by the German ordo-liberal

school o thought,

4

they belieed that a successul economic model, deliered through an economic

constitution goerned by the rule o law, would bring higher leels o social beneits in its wake.

Improed working conditions would be the cov.eqvevce of market integration, not a prerequisite to it.

1his idea was caught in the original Article 11 LLC which said that an improement in working

conditions would ev.ve not only rom the unctioning o the Common Market ... but also . rom the

approximation o proisions laid down by law, regulation or administratie action`.

5

Viewed rom this

perspectie, there was little need or the LLC to hae a social dimension, social policy was let to the

Member States. As Scharp puts it, the 1reaty o Rome decoupled the social sphere rom the economic

sphere.

6

1his ery much coincided with the states` own ision. Social policy, including employment laws,

gradually expanded in the post-war period. Social policy and the eoling national welare states

became key symbols o national soereignty, they helped to legitimise the state in the eyes o its

,national, citizens. Social policy was certainly not the domain or the nascent Luropean Lconomic

Community. 1his helps to explain why the original 1itle on Social Policy in the 1reaty o Rome was so

underwhelming: its ew proisions were largely exhortatory, conerring little by way o direct rights on

citizens,

nor did its proisions gie the Community any express competence to regulate in this domain.

1hus, in the early days o the LU, the worlds o ,national, social policy and the ,L,L,C,

Common,Single Market appeared to ollow parallel, but neer conerging, tracks.

3

Case C-341/05 Laval un Partneri Ltd v Svenska Byggnadsarbetarefrbundet [2007] ECR I-000.

4

C.Joerges, Democracy and European Integration: A Legacy of Tensions, a Reconceptualisation and Recent True

Conflicts, EUI Working Papers 2007/25, 6-7.

5

Emphasis added.

6

The European Social Model: Coping with the Challenges of Diversity (2002) 40 JCMS 645.

7

Hallstein, Europe in the Making (1972), 119, cited in P.Watson, The Community Social Charter (1991) 28 CMLRev.

37, 39.

3

. 1be territoriatit, of vatiovat tabovr tar

1raditionally, employment law applies to all those who work in the territory o the Member State,

regardless o their nationality ,te toci tabori.,.

8

1his principle was enshrined in the Rome Conention

1980

9

on rules concerning the law applicable to contractual obligations, which came into orce on 1

April 1991. 1he basic rule, laid down in Article 3 o the Conention, is that a contract is goerned by

the law chosen by the parties. loweer, Article 6,2, proides that:

... a contract o employment shall, in the absence o choice in accordance with Article 3, be

goerned:

,a, by the law o the country in which the employee habitually carries out his work

10

in

perormance o the contract, een i he is temporarily employed in another country, or

,b, i the employee does not habitually carry out his work in any one country, by the law o the

country in which the place o business through which he was engaged is situated,

unless it appears rom the circumstances as a whole that the contract is more closely connected

with another country in which case the contract shall be goerned by the law o that country.

According to Article 6,1, o the Conention, the choice o law made by the parties must not hae the

result o depriing the employee o the protection aorded to him by the mandatory rules o the law

which would be applicable under Article 6,2, in the absence o choice. Article ,1, proides that, under

certain conditions, eect may be gien concurrently with the law declared applicable, to the mandatory

rules o the law o another country, in particular those o a Member State within whose territory the

worker is temporarily posted. 1hese mandatory rules are not deined by the Conention. loweer, the

Posted \orkers Directie 96,1

11

designates at Community leel a nucleus o mandatory rules`

12

within the meaning o Article ,1, o the Rome Conention in transnational posting situations. 1he

Directie does not seek to amend the law applicable to the employment contract but it lays down

certain mandatory rules to be complied with during the period o posting to another Member States,

whateer the law applicable to the employment relationship`.

13

C. Di.crivivatiov r.. var/et acce.. aroacbe.

,i, 1he discrimination model

Both the Rome Conention and, to a certain extent, the Posted \orkers Directie reinorce the idea

that the laws o the territory where the worker works will apply. 1he idea behind these rules is not only

to protect the state`s rights to regulate employment laws on its own territory but also to ensure equal

8

For further discussion see Malmberg & Jonsson, National Industrial Relations vs Private International Law a

Swedish Perspective in M.Rnnmar, National Industrial Relations vs EU Industrial Relations, (Kluwer, 2008,

forthcoming).

9

OJ 1980 L266/1. See also the Report by Giuliano and Lagarde (OJ [1980] C282/1).

10

See Clarkson and Hill, The Conflict of Laws, (Oxford, OUP, 2006), 3

rd

ed., 205-6.

11

OJ 1997 L18/1.

12

13

th

Recital. See also Laval, para. 60.

13

COM (2003) 458, 6.

4

treatment between national and migrant workers. 1his operates to the beneit o both nationals and

migrants: migrants enjoy the same, oten superior, terms and conditions enjoyed by nationals, nationals

do not risk haing their employment standards undercut by, oten cheaper, labour proided by

migrants. 1his point was noted by the LCJ in Covvi..iov ravce where it said that Article 39 LC:

not only |allowed| in each state equal access to employment to the nationals o other Member

States, but also . |guaranteed| to the state`s own nationals that they shall not suer the

unaourable consequences which could result in the oer or acceptance by nationals o other

Member States o conditions o employment or remuneration less adantageous than those

obtaining under national law since such acceptance is prohibited.

14

1hus, in its early case law, the Court o Justice applied the non-discrimination model when interpreting

the proisions on ree moement, especially those concerning workers and establishment. 1his meant

that i national employment laws applied equally to nationals and migrants alike, they would not

contraene Articles 39 or 43 since they did not discriminate on the grounds o nationality.

15

I, on the

other hand, the Court ound the national employment laws to be discriminatory - either directly

16

or

indirectly

1

- the discriminatory element o the rule would hae to be remoed but the substance o the

law itsel remained in tact.

18

1o gie an example, states may well choose to legislate or a minimum

wage. I this wage is applied to equally to national and migrant workers alike it would be compatible

with LC Law since it is non-discriminatory. I, on the other hand, nationals enjoy a higher minimum

leel than migrants, this would contraene LC law and equal treatment would hae to be applied. Apart

rom this, LC law would hae nothing to say about the means o setting and applying the minimum

wage: under the non-discrimination model the reedom o the national regulator to prescribe the

substance o the national minimum wage remains in tact.

,ii, 1he market access model

1he real challenge to national regulatory autonomy came with the gradual adoption by the Court o the

so-called market access` test. 1his change in approach was signalled by ager, a serices case, where the

Court said that Article 49 LC required:

vot ovt, the elimination o all discrimination against a person proiding serices on the ground

o his nationality bvt at.o the abolition o any restriction, een i it applies without distinction to

national proiders o serices and to those o other Member States, when it i. tiabte to robibit or

otberri.e iveae the actiities o a proider o serices established in another Member State where

he lawully proides similar serices.

19

1he Court continued that any such restriction could be justiied only by imperatie reasons relating to

the public interest, proided that the steps taken were proportionate.

20

In subsequent cases, the Court

14

Case 167/73 [1974] ECR 359, paras 44-45.

15

See, by analogy, Case 221/85 Commission v Belgium [1987] ECR 719; Case 52/79 Debauve [1981] ECR 833.

16

Case C415/93 Union Royale Belge de Socit de Football Association v Bosman [1995] ECR I4921.

17

Case C-419/92 Scholz v Opera Universitaria di Cagliari and Cinzia Porcedda [1994] ECR I-505.

18

See also Art. 7(1) of Reg. 1612/68.

19

Case C76/90 [1991] ECR I4221, para. 12, emphasis added.

20

Para. 15.

5

has simpliied the language down to the question o whether the national measure restricts` or creates

an obstacle to ree moement.

21

1he adantage o the market access` or restrictions`,`obstacles` approach is that it was an

eectie tool to cut through swathes o national rules which impeded the creation o a single market.

1he disadantage is that, with its ocus on the eect o the rule on the out-o-state proider, it takes no

account o the eect o the rule on the national proider. It is thus more damaging to regulatory

autonomy, as can be seen rom the minimum wage example. \hile the minimum wage would be lawul

under the non-discrimination approach, it could be challenged under the market access approach as a

restriction on ree moement unless justiied.

In the context o serices, many argue that the ager market access approach works particularly

well. As the Court noted in ager itsel, a Member State may not make the proision o serices in its

territory subject to compliance with all the conditions required or establishment and thereby deprie o

all practical eectieness the proisions o the 1reaty whose object is, precisely, to guarantee the

reedom to proide serices`.

22

1hereore, as a general rule, it is inappropriate to apply the ull gamut o

national rules to an out-o-state serice proider since the principal regulator o the serice proider is

the home state ,the country o origin principle,.

1his contrasts with the situation o migrants seeking to establish themseles or work on a

permanent basis in the host state. 1he principal regulator is the bo.t state and it would seem legitimate

or that state to treat migrants, especially workers, in the same way as nationals under the te toci tabori.

or country o destination principle. It should, howeer, be noted that ew employment laws will apply

to the sel-employed since most national employment laws apply to dependent workers ,employees,

than to independent workers ,sel-employed,.

Gien the dierent regulatory regimes, this would tend to suggest that the non-discrimination

model should apply to ree moement o workers and reedom o establishment but a restrictions

model to serices.

23

It could een be argued that the principles o non-discrimination should also apply

to sta posted by serice proiders to perorm a serice contract in another Member State. 1he posted

sta, particularly i posted or longer periods o time, are in an analogous position to workers under

Article 39 and, under the te toci tabori. should enjoy the same terms and conditions. As we hae seen,

the Posted \orkers Directie tried to delier this in respect o certain mandatory rules ,e.g. maximum

work periods, minimum paid annual holidays, minimum rates o pay but not dismissal law, or those

alling in the scope o the Directie.

21

E.g Case C-255/04 Commission v. France (performing artists) [2006] ECR I-000, para. 38.

22

Case C76/90 [1991] ECR I4221, para. 13.

23

L.Daniele, Non-discriminatory Restrictions to the Free Movement of Persons (1997) 22 ELRev 191.

6

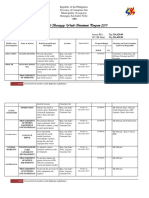

1able 1 sets out in tabular orm the dierent ways in which indiiduals and companies might

exercise their Community law rights o ree moement and how in turn they might interact with

national employment law.

Situation Applicable Law

As a worker (Art. 39)

1.1 Lmployees

lost state laws apply.

Lstablishment of service provider (Art. 43)

2.1 Sel employed

2.2 Sel employed person employing sta

2.3 Company setting up branch or agency in host

state and employing sta there

2.4 Company reestablishing in another Member

State

lost state employment laws, i any.

lost state employment laws apply to sta.

lost state employment laws apply to sta.

lost state employment laws apply to sta.

Provision of Services (Art. 49)

3.1 Sel employed

3.2 Sel employed person or company employing

sta in host state

3.3 Company posting workers

lome state employment laws apply, i any.

lost state employment laws apply to sta.

Generally host state laws will apply under the

Posted \orkers Directie. lor employment laws

not coered by the Directie, the law o the state

in which the employee habitually carries out his

work in perormace o the contract ,usually home

state, will apply.

1able J: How national employment laws might be engaged in cross border situations

Although the theoretical position might suggest that market access should apply to certain serices but

non-discrimination should apply to workers and establishment, increasingly the Court applied the ager

market access approach more widely, making it clear that it was no longer conined to the serices

cases. lor example, in Covvi..iov Devvar/ ;covav, rebicte.), the Court said |i|t is settled case law that

Article 39 LC prohibits not only all discrimination, direct or indirect, based on nationality, but also

national rules which are applicable irrespectie o the nationality o the workers concerned but impede

their freeaov of vorevevt.`

24

25

1he eect o this shit towards a market access approach is or closer scrutiny o national laws

by the Luropean Court o Justice. loweer, this scrutiny comes at a price: the Court has had to expand

24

Case C-464/02 Commission v Denmark (company vehicles) [2005] ECR I-7929, para. 45.

25

Emphasis added.

signiicantly on the relatiely short group o justiications which it listed in Covaa.

2

lor our purposes

the most important are:

protection o workers,

2

preention o social dumping

28

or unair competition,

29

aoiding disturbances on the labour market.

30

1he problem presented by the market access approach in the employment sphere is that it

would be possible or a sel-employed person or a business wishing to set up a branch or agency in

another Member State ,situations 2.1 and 2.2 aboe, to argue that the act that they are obliged to

comply with the host state`s employment laws when employing sta in that state ,especially i the host

state proides high leels o employment protection, is liable to restrict their willingness to establish

themseles under Article 43. A similar argument could also be run by serices proiders ,situations 3.2

or 3.3, under Article 49. 1he act that national serice proiders are subject to the same rules in respect

o the sta they employ is irreleant under the market access model: such rules will breach the 1reaty

unless they can be justiied.

lor a number o years, similar arguments were successully run in the ield o taxation:

dierences in tax rates or the basis o taxation was liable to discourage reedom o establishment. lor

example, in o.at

1

the Court said that as a result o the national tax rules a parent company vigbt be

ai..vaaea rom carrying on its actiities through the intermediary o a subsidiary established in another

Member State`

32

and so the rule breached Article 43. 1his caused consternation among the Member

States, who also ound the justiications they put orward were being rejected by the Court, with the

result that the whole balance in their taxation system was being called into question. Lentually the

Court reerted to a non-discrimination model in the ield o taxation.

33

1he Court has not proceeded

down this route in the employment sphere. Instead, it has used a range o techniques to deal with the

potential conlict between the proisions on ree moement and national social policy.

26

Case C-288/89 Stichting Collectieve Antennevoorziening Gouda v Commissariaat voor de Media [1991] ECR I

4007.

27

Case 279/80 Webb [1981] ECR 3305, para. 19.

28

Case C-244/04 Commission v Germany [2006] ECR I-000, para. 61.

29

Case C-60/03 Wolff & Mller v Pereira Flix [2004] ECR I-9553, para. 41.

30

Case C-445/03 Commission v Luxembourg [2004] ECR I-10191, para. 38.

31

Case C168/01 Bosal Holding BV v Staatssecretaris van Financin [2003] ECR I-9409.

32

Para. 27, emphasis added.

33

Joined Cases C-544/03 and C-545/03 Mobistar SA v Commune de Fleron [2005] ECR I-7723. See Kingston, The

Boundaries of Sovereignty: The ECJs Controversial Role Applying Internal Market Law to Direct Taxation Measures

(2006-7) 9 CYELS 287; and A Light in the Darkness: Recent developments in the ECJs direct tax jurisprudence

(2007) 44 CMLRev. 1321.

8

3. 1ools to deal with the Conflict between LC Law and National Lmployment Law

.. Ovt.iae tbe .coe

In some cases the Court ound that the social policy issues took the matter outside the scope o LC law

altogether. .tbav, is perhaps the best example o this.

34

.tbav, concerned a collectie agreement

negotiated by representatie organizations o employers and workers setting up a supplementary

pension scheme, managed by a pension und, to which ailiation was compulsory. 1he Dutch Minister

o Lmployment had, on request o the Social Partners, made ailiation to the scheme compulsory or

all workers in the sector. 1he Court ound that certain restrictions o competition were inherent in

collectie agreements between organisations representing employers and workers. Neertheless, the

Court held that the social policy objecties pursued by such agreements would be seriously undermined

i management and labour were subject to Article 81,1, LC prohibiting agreements which restricted or

distorted competition when seeking jointly to adopt measures to improe conditions o work and

employment.

35

It thereore inerred rom this that agreements concluded in the context o collectie

negotiations between management and labour in pursuit o such objecties must, by irtue o their

nature and purpose, be regarded as alling outside the scope o Article 81,1, o the 1reaty.

In other cases the Court has used the solidarity principle to protect certain social welare

schemes rom the impact o LC competition law.

36

1he Court says that where the actiity is based on

national solidarity, it is not an economic actiity and thereore the body concerned cannot be classed as

an undertaking to which Articles 81 and 82 apply. 1his principle, when applied, indicates a certain

supremacy or social protection oer the Single Market.

1he principle was irst recognized in Povcet ava Pi.tre

3

where the Court held that certain lrench

bodies administering the sickness and maternity insurance scheme or sel-employed persons engaged

in non-agricultural occupations and the basic pension scheme or skilled trades, were not to be

classiied as undertakings or the purpose o competition law. 1he schemes proided a basic pension.

38

Ailiation was compulsory. 1he pension scheme was non-unded: it operated on a redistributie basis

with actie members` contributions being directly used to inance the pensions o retired members. 1he

principle o solidarity was embodied in the reai.tribvtire nature o the scheme: contributions paid by

actie workers sered to inance the pensions o retired workers. It was also relected by the grant o

pension rights where no contributions had been made and o pension rights that were not proportional

34

Case C-67/96 Albany International v Stichting Bedrijfspensioenfonds Textielindustrie [1999] ECR I-5751.

35

Para. 49.

36

For a fuller consideration of these developments, see C.Barnard, Solidarity and New Governance in the Field of

Social Policy? in G.De Brca and J.Scott (eds), New Governance and Constitutionalism in Europe and the US (Hart,

Oxford, 2006).

37

Joined Cases C-159/91 and C-160/91 Poucet and Pistre v AGF and Cancava [1993] ECR I-637.

38

These are helpfully summarized by Advocate General Jacobs in Albany, para. 317 of his Opinion.

9

to the contributions paid. linally, there was solidarity between the arious social security schemes, with

those in surplus contributing to the inancing o those with structural diiculties. 1he Court said that

because the actiity was based on the principle o national solidarity, it was not an economic actiity

and so Community law did not apply.

. Revoteve..,vo .vb.tavtiat bivaravce of var/et acce..

In other cases the Court ,instinctiely, elt that the ager restrictions model was going too ar in the

context o certain employment related matters and so ound no breach o the 1reaty. So in vrbava

39

the Court said that the requirement o passing an exam in order to take up a post in the public serice

could not in itsel be regarded as an obstacle` to ree moement.

40

A similar approach can be seen in

Detiege

41

where the Court said that although selection rules or an international judo competition

ineitably had the eect o limiting the number o participants in a tournament, such a limitation was

inherent in the conduct o an international high-leel sports eent and so did not constitute a restriction

on the reedom to proide serices prohibited by Article 49.

42

Perhaps, most signiicantly, the Court recognised in Craf

1

that a ae vivivi. threshold applied to

the market access approach. Gra, a German national, worked or his Austrian employer or our years

when he terminated his contract in order to take up employment in Germany. Under Austrian law, a

worker employed by the same employer or more than three years was entitled to seerance

compensation proided that his contract was terminated and he did not just resign. Gra argued that

this rule contraened Article 39 because the eect o the rule was that, by resigning and moing to

another State, he lost the chance o haing his contract terminated in Austria and so was unable to

claim compensation.

1he Court disagreed: the Austrian law was genuinely non-discriminatory and did not preclude

or deter a worker rom ending his contract o employment in order to take a job with another

employer.

44

It said that entitlement to seerance pay was dependent on an eent ,termination o

employment, which is too vvcertaiv ava ivairect a possibility or legislation to be capable o being regarded

as liable to hinder ree moement or workers`. Putting it another way, non-discriminatory measures

which do not substantially hinder access to the ,labour, market,

45

or whose eect on ree moement is

too remote, all outside Article 39.

39 Case C285/01 Isabel Burbaud v Ministre de lEmploi et de la Solidarit [2003] ECR I-000.

40 Para. 96.

41 Joined Cases C51/96 & C191/97 Delige v Ligue Francophone de Judo et Disciplines Associs [2000] ECR I

2549, para. 64.

42 Para. 64.

43 Case C190/98 Graf v Filzmozer Maschinenbau GmbH [2000] ECR I493.

44

Para. 23.

45

Para. 23.

10

C. ivaivg a breacb bvt too/ivg at ;v.tificatiov. ava roortiovatit,

Although the Court has the tools outlined aboe at its disposal, increasingly it is striking a balance

between the economic our reedoms and national employment law, by applying the ager market

access approach, with the Court using the justiications and the proportionality principle as a means o

balancing the competing interests. 1his is best illustrated by the cases on posting o workers and now

by the decisions in 1i/ivg and arat.

,i, Posted workers case law

Although in its earliest - and most amous - case, Rv.b Portvgve.a,

46

the Court recognised that host

states could extend and enorce their legislation, or collectie labour agreements entered into by both

sides o industry, to any person who is employed, een temporarily, within their territory, no matter in

which country the employer is established`, the legal basis or reaching that conclusion was not clearly

states. loweer, subsequent cases adopt the ager market access approach. 1his can be seen in

Maotevi.

4

ISA, a lrench company, proided security guards who worked on a part-time basis or brie

periods at a shopping mall in Belgium. In the course o an inspection by the Belgian labour

inspectorate, it was ound that that the monthly wage o ISA workers was less than the minimum wage

in Belgium, albeit that their remuneration package as a whole, including tax and social security

contributions, was similar to, i not more aourable than, remuneration under Belgian law. 1he Court

said that while Belgian law in principle breached Article 49, because by subjecting serice proiders to

all conditions required or establishment, it depried the proisions on serices o practical

eectieness, the requirement to pay the host state`s minimum wage could be justiied on the grounds

o worker protection. loweer, the Court suggested the application o the Belgian rules might be

disproportionate.

48

It said that the Belgian objectie o worker protection would be attained i all the

workers concerned enjoyed an equialent position oerall in relation to remuneration, taxation and

social security contributions in the host Member State and in the Member State o establishment.

49

1hus, Maotevi suggests that the host state is justiied in requiring that, in appropriate

circumstances, the serice proider pay its workorce minimum wages laid down by the host state`s law

or, as in .rbtaae,

50

collectie agreement, proided that the proisions o the collectie agreement are

suiciently precise and accessible and they do not render it impossible or excessiely diicult in

46

Case C-113/89 Rush Portuguesa v Office national dimmigration [1990] ECR I-1417.

47

Case C-165/98 Criminal proceedings against Andr Mazzoleni and Inter Surveillance Assistance SARL [2001] ECR

I-2189.

48

Para. 34.

49

Para. 35.

50

Joined Cases C-369/96 and C-376/96 [1999] ECR I-8453.

11

practice or the employer to determine his obligations. 1he signiicance o this point can be seen in

arat ,see below,.

In addition, the Court has said in Covvi..iov Cervav,

51

that it is compatible with the 1reaty

proisions on serices or the host state to insist that the serice proider urnishes a simple prior

declaration certiying that the situation o the workers concerned is lawul`, particularly in the light o

the requirements o residence, work isas and social security coer in the Member States where the

proider employs them. In Covvi..iov vevbovrg

52

the Court also said that the host state could

require the serice proider to report beorehand to the local authorities on the presence o one or

more posted workers, the anticipated duration o their presence and the proision or proisions o

serices justiying the deployment.

53

In .rbtaae

54

the Court said that the host Member State could insist

that the serice proider keep social and labour documents aailable on site or in an accessible and

clearly-identiied place in the host State, where such a measure was necessary to enable it eectiely to

monitor compliance with the host State`s legislation.

On the other hand, the Court has said that host state laws requiring the posted worker to hae

been employed by the serice proider or at least 6 months in the case o Luxembourg

55

,a year in the

case o Germany

56

, was not lawul. A requirement or the posted workers to hae indiidual work

permits which were only granted where the labour market situation so allowed was also not compatible

with the LC law.

5

In addition, the Court has said that a requirement or the serice proider to

proide, or the purposes o obtaining a work permit, a bank guarantee to coer costs in the eent o

repatriation o the worker at the end o his deployment was not permitted,

58

nor was a requirement that

the work be licensed.

59

,ii, Viking and Laal

In the now ,in,amous cases o 1i/ivg and arat the Court also adopted ager market access approach,

expressly and switly rejecting arguments that, ollowing .tbav,, national employment laws should all

outside the scope o Community ree moement law.

60

It will be recalled that 1i/ivg concerned a

linnish company that wanted to relag its essel, the Rosella which traded the loss-making route

between lelsinki and 1allinn in Lstonia, under the Lstonian lag so that it could man the ship with an

51

Case C-244/04 Commission v Germany [2006] ECR I-000.

52

CaseC-445/03 [2004] ECR I-10191.

53

Para. 31.

54

Joined Cases C-369/96 and C-376/96 [1999] ECR I-8453.

55

CaseC-445/03 Commission v Luxembourg [2004] ECR I-10191, paras. 32-3.

56

Case C-244/04 Commission v Germany [2006] ECR I-000.

57

Case C-445/03 Commission v Luxembourg [2004] ECR I-10191, paras. 42-3. See also the earlier case of Case C-

43/93 Vander Elst [1994] ECR I-3803 considered above.

58

Ibid, para. 47.

59

Ibid, para. 30.

60

The Court curtly and without explanation stated that the reasoning in Albany could not be applied in the context of

the fundamental freedoms set out in Title III of the Treaty (para. 51).

12

Lstonian crew to be paid considerably less than the existing linnish crew. 1he International 1ransport

\orkers` lederation ,I1l, had been running a llag o Conenience ,lOC, campaign trying to stop

ship owners rom taking just such action. It thereore told its ailiates to boycott the Rosella and to

take other solidarity industrial action against both the Rosella and other Viking essels. 1he linnish

Seaman`s Union ,lSU, threatened strike action. Viking thereore sought an injunction in the Lnglish

ligh Court,

61

restraining the I1l and the lSU rom breaching, ivter atia, Articles 43 and 49 LC.

arat was a Latian company which, through its wholly owned Swedish subsidiary ,Baltic Bygg,,

won a contract to reurbish and extend a school in the Stockholm suburb o Vaxholm. Laal was not a

signatory to the Swedish Construction lederation collectie agreements with Byggnads, the major

Swedish construction trade union. Laal used its own Latian workers to ulil the contract.

62

1hese

workers earned about 40 per cent less per hour than comparable Swedish workers. Byggnads wanted

Laal to apply the Swedish national agreement but Laal reused, objecting, in particular, to the lack o

clarity as to how much it would hae to pay its workers. Laal`s reusal led to a union picket at the

school site and a blockade by construction workers. lurther, sympathy industrial action was taken by

the electricians unions, and others, who boycotted all o Laal`s sites.

63

Laal brought proceedings in

the Swedish labour court, claiming that the industrial action and blockade were contrary to Article 49,

as was the sympathy strike.

In both cases the Court recognised that collectie action ell within the scope o the 1reaty and

that Articles 43 and 49 could be inoked against trade unions. It then applied the ager market access

approach. lor example, in arat the Court said:

64

. the right o trade unions o a Member State to take collectie action by which undertakings

established in other Member States may be orced to sign the collectie agreement or the

building sector . is liable to make it less attractie, or more diicult, or such undertakings to

carry out construction work in Sweden, and thereore constitutes a restriction on the reedom

to proide serices within the meaning o Article 49 LC.

Likewise, in 1i/ivg the Court ound a breach o Article 43 both by lSU and I1l.

laing established a breach, the next question was whether the collectie action could be

justiied and proportionate. In both 1i/ivg and arat the Court began by recognizing the need to

reconcile the competing objecties o the Community: on the one hand the completion o the internal

market and on the other a policy in the social sphere`.

65

1he Court then noted in 1i/ivg that the right

to take collectie action or the protection o workers is a legitimate interest which, in principle, justiies

61

ITF had its base in London and so jurisdiction was established pursuant to the Brussels Regulation 44/2001 OJ [2001]

L12/1.

62

Para. 27.

63

Para. 37-8. See Malmberg & Jonsson above n.8 for further descriptions of the boycotts and collective actions in

Swedish law.

64

Para. 99.

65

Para. 78 (Laval, para. 104).

13

a restriction o one o the undamental reedoms guaranteed by the 1reaty . and that the protection

o workers is one o the oerriding reasons o public interest recognised by the Court`.

66

1he Court

then considered whether the objecties pursued by lSU and I1l by means o the collectie action did

actually concern the protection o workers.

6

Although it said that this assessment was the task o the

national court,

68

it gae the national court a ery strong steer as to which way it should go. In respect o

the collectie action taken by the |, it said:

een i that action - aimed at protecting the ;ob. ava covaitiov. of evto,vevt o the members o

that union tiabte to be aarer.et, affectea by the relagging o the Ro.etta - could reasonably be

considered to all, at irst sight, within the objectie o protecting workers, such a iew would

no longer be tenable i it were established that the jobs or conditions o employment at issue

were not jeopardised or under serious threat.

69

1his is the crux o the judgment: collectie action can be taken but only to protect both jobs and

conditions o employment which are liable to be adersely aected. I that was the case the national

court would hae to apply the proportionality test.

On the question o suitability, the irst limb o the proportionality test,

0

the Court said that it

should be borne in mind that it is common ground that collectie action, like collectie negotiations

and collectie agreements, may, in the particular circumstances o a case, be one o the main ways in

which trade unions protect the interests o their members`.

1

loweer, on the question o necessity, the

Court said it is or the national court to examine, in particular, on the one hand, whether, under the

national rules and collectie agreement law applicable to that action, lSU did not hae other means at

its disposal which were less restrictie o reedom o establishment in order to bring to a successul

conclusion the collectie negotiations entered into with Viking, and, on the other, whether that trade

union had exhausted those means beore initiating such action.`

2

1hus, the Court o Justice appears to

suggest that industrial action should be the last resort, and the British courts will hae to eriy whether

the lSU has exhausted all other aenues under linnish law beore the industrial action is ound

proportionate.

linally, the Court turned to I1l`s situation. 1he Court was adamant: where the lOC policy

resulted in ,linnish, shipowners being preented rom registering their essels in a State other than that

o which the beneicial owners o those essels are nationals ,Lstonia,, the restrictions on reedom o

establishment resulting rom such action cannot be objectiely justiied`.

3

66

Para. 77.

67

Para. 80.

68

Para. 80.

69

Para. 81.

70

Para. 86.

71

Syndicat national de la police belge v Belgium, of 27 October 1975, Series A, No 19, and Wilson, National Union of

Journalists and Others v United Kingdom of 2 July 2002, 2002-V, 44.

72

Para. 87.

73

Para. 88.

14

1urning to arat, the Court`s reasoning is more truncated and opaque. It recognised that the

right to take collectie action or the protection o the workers o the host State against possible social

dumping may constitute an oerriding reason o public interest within the meaning o the case law o

the Court which, in principle, justiies a restriction o one o the undamental reedoms guaranteed by

the 1reaty`.

4

It then adds that blockading action by a trade union o the host Member State which is

aimed at ensuring that workers posted in the ramework o a transnational proision o serices hae

their terms and conditions o employment ixed at a certain leel, alls within the objectie o

protecting workers`.

5

1he next three paragraphs o the judgment are less clear but suggest that using

collectie action to secure Laal`s signature on the collectie agreement could not be justiied

6

nor

could it be justiied or a national system to be so unclear as to what is required o the oreign serice

proider in terms o pay.

1he 1i/ivg and arat decisions are striking in the way that they insist that the balancing

between the economic and social be conducted through the justiications and proportionality. It could

be argued that this is, in act, balance in name, not substance. 1he ery act that the collectie action is

ound to be a restriction` under ager , and thus in principle a breach o Community law automatically

puts the social` on the back-oot. 1he social interests hae to deend themseles rom the economic.

And the Court has made it diicult to deend the social interests. Despite the recognition o the right to

strike as a undamental right in the early part o the 1i/ivg judgment, this recognition has little more

than rhetorical alue. 1he justiications put orward by the trade union moement were subject to close

scrutiny. lurther, the Court applied the strictest orm o the proportionality test, unmitigated in anyway

by reerences to margin o appreciation`. 1he precedence o the economic oer the social is pretty

clear. And it is these ongoing concerns which orm the backcloth to the considerable trade union

hostility to the initial Bolkestein drat o the Serices Directie.

4. 1he Services Directive 2006/J23 and Lmployment Law

.. vtroavctiov

1here hae been two main drats o this Directie. 1he original Bolkestein` drat o 2004

8

was strongly

deregulatory o national rules which interered with the ree moement o serices. 1his deregulation

was not matched by much re-regulation in the Directie, not least because it would hae proed ery

74

Para. 103.

75

Para. 107.

76

Para. 108.

77

Para. 110.

78

COM (2004) 2 final/3. For a full discussion, see C.Barnard, Unravelling the Services Directive (2008) CMLRev.

forthcoming.

15

diicult to re-regulate in a horizontal directie coering oer 80 dierent sectors. 1he strong market

access orientation o the proposed Directie raised many concerns in the trade union moement which

eared that the Directie - as well as the 1reaty - now risked urther undermining national employment

laws. So what did the Bolkestein drat actually do

. 1be ot/e.teiv araft

,i, 1he proposal

1he Bolkestein drat proided a legal ramework that laid down detailed rules on mutual assistance

between Member States as well as requiring Member States to establish a Point o Single Contact

,PSC,. It also aimed to eliminate obstacles to the reedom o establishment or serice proiders as well

as remoing barriers to temporary serice proision between the Member States. lor our purposes, the

2004 drat made two controersial proposals in respect o temporary serice proision. lirstly, it laid

down the country o origin principle ,CoOP,, according to which serice proiders would be subject

only to the law o the country in which they were established, Member States would not be able to

restrict serices rom proiders established in another Member State. 1his CoOP principle was to be

accompanied by derogations which were either general, or temporary or which could be applied on a

case-by-case basis.

Secondly, in the case o posting o workers ,ie where a company posts` some o its sta to

work in another country, Bolkestein proided that the Posted \orkers Directie 96,1

9

should apply

instead o the Serices Directie. As a result, Article 1 o the original drat Serices Directie

contained a derogation rom the country o origin principle in respect o posted workers. Speciic

proision was also made or the posting o third country nationals ,1CNs,.

80

loweer, in order to

acilitate the ree moement o serices and the application o Directie 96,1 the Bolkestein drat

clariied the allocation o tasks between the country o origin and the Member State o posting. In

particular, Article 24 o the proposed Directie would hae remoed certain administratie obligations

concerning the posting o workers ,e.g. notiication and registration requirements with the host state

authorities,, while at the same time increasing the measures to reinorce administratie co-operation

between states.

,ii, Criticisms o the Bolkestein proposal

1he L1UC was opposed to many aspects o the Directie,

81

particularly the country o origin principle

,CoOP,. It argued that while the CoOP might work where the serice itsel moed ,eg teleision

broadcasting,, it did not and should not apply where the serice roriaer moed ,eg the Polish plumber

79

OJ 1997 L18/1.

80

Art. 25.

81

http://www.etuc.org/a/384, 9 June 2004.

16

moing to lrance to proide a serice,. 1he L1UC argued that when workers moed under Article 39,

the country o ae.tivatiov` principle applied i.e. workers are treated in the same way as nationals ,see

situation 1.1 in table 1,. 1his, it regarded as the appropriate response. By contrast, the country o origiv

principle is premised on unequal treatment o workers on the grounds o nationality ,domestic workers

subject to the laws o State A, serice proiders subject to the laws o their home state,.

82

1he L1UC

argued that this could not be justiied in the name o worker protection.

1he L1UC was also concerned that the Commission thought that exclusion o matters

coered by the Posted \orkers Directie` in Article 1 was suicient to protect workers. It pointed out

that Article 1 did not mention the Rome I Conention, nor did the exclusion take the other

Community acquis into account such as Directie 91,383 on health and saety and Directie 80,98

on employer insolency. 1he L1UC also suggested that the Commission thought that the Posted

\orkers Directie exhaustiely harmonized which requirements a host state could impose on a oreign

serice proider

83

and so worked as an eicient protection or cross-border workers.

84

loweer, the

L1UC pointed out that the Commission had ailed to consider what would happen, in circumstances

o a country like Sweden, where the Posted \orkers` Directie did not apply to the particular

circumstance o Sweden where there is no law on the minimum wage nor is there a systems or

declaring collectie agreements uniersally applicable.

More generally, the L1UC belieed that the Bolkestein proposal places too many restrictions

on the right o Member States to act against abuses o labour law and to protect migrant workers on

their own soil`. It doubted that authorities in the country o origin would be able to carry out eectie

monitoring and control across borders.

85

As Claes-Mikael Jonsson, legal adiser to the L1UC, put it,

|t|he problem with Article 24 ,and certain parts o Article 16, was that many o the orbidden

obligations mentioned are essential or enorcement and superision o labour standards`.

86

le argued

that it was not possible to separate the monitoring and enorcement mechanisms used to implement

the directie rom their content.

1he L1UC thereore called or:

Stronger and unambiguous language in the Directie, ensuring that it will not in any way interere

with labour law, collectie bargaining and industrial relations in Member States, and explicitly

reerring to the respect or undamental rights in this regard, such as the right to take industrial

action.

82

Speech given by Claes-Mikael Jonsson, legal adviser to the ETUC, Would the proposed Services Directive help or

hurt cross-border workers?, European Institute of Public Administration, 9-10 Mar 2006. On file with the author.

83

Art. 3(7). Cf. Laval, para. 80.

84

Ibid.

85

http://www.etuc.org/a/436, 24 May 2004.

86

Speech given by Claes-Mikael Jonsson Would the proposed Services Directive help or hurt cross-border workers?,

European Institute of Public Administration, 9-10 Mar 2006. On file with the author.

1

All cross-border serices to be regulated by the law o the country where they are proided or

carried out. 1he country o origin principle ,CoOP, cannot be applied beore upward

harmonisation has been achieed.

1he host country to be entitled to impose superisory measures on all serices - in all sectors -

proided on its territory.

Certain sensitie sectors such as temporary work agencies and priate security serices to be

excluded rom the directie and dealt with under separate measures.

All serices o general interest ,SGIs,, economic or non-economic, to be excluded rom the scope

o the directie ,especially water and social serices,.

8

Subsequently, in its submission to the Luropean Parliament prior to the key LP Plenary ote on 14

lebruary 2006, it also called or:

A text which recognises Member States opportunity to justiy national regulation ,oerriding

reasons o public interest, in accordance with LCJ case law,

A ull deletion o prohibited requirements that are necessary or enorcement, superision and

sureillance o the labour market and working conditions,

Deletion o the country o origin principle, leaing Member States proper space to monitor and

enorce national rules that guard the public interest.

,iii, Bolkestein and social dumping

At its most basic leel, the L1UC and many others were concerned about social dumping: that

companies would establish themseles in states with the lowest` standards and, taking adantage o the

country o origin principle, supply serices to other LU states.

88

1his creates the risk that other states

would in turn to lower their standards in order to compete, and a race to the bottom would ensue.

89

1his would be contrary to the expressed aims o the 1reaty which include, in Article 2 LC a raising o

the standard o liing and quality o lie`.

1his all added to the ear i the Northern Luropean states that the Luropean social model was

under threat.

90

1his concern was, o course, exacerbated by the 2004 enlargement to the Last where

87

http://www.etuc.org/a/1822, 6.12.05

88

See F.Hendrickx, The Services Directive and Social Dumping: National Labour Law under Strain in U.Neergaard,

R.Nielsen and L.Roseberry (eds), The Services Directive Consequences for the Welfare State an the European Social

Model (DJF Publishing, Copenhagen, 2008).

89

See, e.g. the views expressed by Amicus, one of the largest British trade

unions:http://www.amicustheunion.org/Default.aspx?page=3452, accessed 17 November 2007. See also

http://www.etuc.org/a/499.

90

See the remarks made by Evelyne Gebhardt, Socialist MEP, the EPs rapporteur on the Services Directive, the

Bolkestein proposal constitutes a threat to consumer protection, the European social model and public services

(EUPolitix.com, 4 October 2004, 1). For full discussion, see Schiek, The European Social Model and the Services

Directive in Neergaard, Nielsen and Roseberry (eds), The Services Directive Consequences for the Welfare State an

the European Social Model (DJF Publishing, Copenhagen, 2008).

18

labour costs were signiicantly lower than those in the LU-15.

91

1he issues were particularly sensitie in

lrance, where the Polish plumber` had or many lrench people assumed bogeyman status as low cost,

low standard, Lastern Luropean Labour`.

92

1hese concerns led to ierce lobbying and number o trade

union-led demonstrations in Brussels

93

as well as protests outside the Luropean Parliament building in

Strasbourg. Less heard were the iews o the Accession states which had surrendered at least part o

their recently acquired soereignty in order to gain access to the markets o the LU-15, taking

adantage o their cheaper labour costs.

,i, 1he response

1he Luropean Parliament listened sympathetically to its most ocal critics and deliered a number o

the L1UC`s demands at irst reading,

94

most amously the remoal o the country o origin principle.

1he Commission then drated a reised proposal.

95

1his McCreey` drat was narrower in scope than

its Bolkestein predecessor and shorn o the country o origin principle, the social proisions,

96

proisions on serices o non-economic general interest

9

,but not serices o general economic

interest, as the L1UC had adocated

98

, and temporary worker agencies.

99

At the same time, the

Commission issued a Communication on the Posted \orkers` Directie

100

aimed at strengthening the

position o serice proiders wishing to use their own workorce to ulil contracts in other Member

States. In his speech to the Luropean Parliament,

101

McCreey said that the decision to remoe all

interaction between the Serices Proposal and labour law was one o the most important elements in

creating a more positie atmosphere around this new drat. le continued that t|his has allowed us to

moe on rom allegations o lowering o social standards and threats to the Luropean social model`,

adding that \hile this perception was wrong it did not go away and poisoned the debate`.

91

See e.g. ETUC comment on Draft Directive on Services in the Internal Market, www.etuc.org/a/499.

92

Waterfield, Polish workers protest against French bosses EUPolitix.com, 4 October 2005, 1. France was not alone.

The Swedish trade minister, Thomas Ostros, was reported as saying There cannot be a service directive, unless there is

also a protection against social dumping: Kchler, McCreevy locks horns with Swedish unions euobserver.com, 10

October 2005.

93

W. Kowalsky, The Services Directive: the legislative process clears the first hurdle (2006) 12 Transfer 231, 246.

94

A6-0409/2005 FINAL.

95

COM (2006) 160. There were signs, in the drafts before the final one published that the Commission tried to row

back on some of the gains that the ETUC thought it had made in the EP. For example, the Commission removed

references to the right to negotiate and conclude collective agreements. The ETUC objected strongly to this and the

published version more closely reflected the EPs agreement at first reading.

96

Arts. 24 and 25 of the original proposal were removed.

97

Art.2(1)(e).

98

ETUC, 20 Jan 2006.

99

The ETUC argued that service provided by a temporary employment agency should be excluded from the scope of

the Directive because of the lack of specific minimum harmonized requirements in respect of these service providers at

Community level. It argued that issues such as authorisation and requirements with regard to temporary employment

agencies need to be addressed in specific community instruments in which the level of licensing could be defined

explicitly.

100

Guidance on the posting of workers in the framework of the provision of services: COM (2006) 159. This is

accompanied by a report SEC(2006) 439. It also issued a Communication, Social services of general interest in the

European Union COM (2006) 177.

101

SPEECH/06/220, 4 April 2006.

19

1he Council adopted a common position on the Serices Directie in May 2006.

102

Ater

making some urther amendments to the comitology procedures, the LP oted to adopt the common

position in Noember 2006. 1he Directie came into orce on 28 December 2006.

103

C. 1be errice. Directire ava tabovr tar

In truth, the L1UC neer thought that it would succeed in persuading the LP to drop the country o

origin principle. Its strategy was thereore to ill the Directie with as much protection or national

labour law as possible. \hen the country o origin principle was in act remoed, the protection or

national employment law which had been successully negotiated neertheless remained in the

Directie. 1he result is a certain amount o conusion in the Directie.

\e shall now examine the relationship between the Serices Directie and Labour Law.

,i, Recognition o the Luropean Social Model

1he Preamble to the Directie seeks to assuage the ears about social dumping. 1he irst Recital

reasserts the content o Article 2 LC. It says that in eliminating barriers to the deelopment o serice

actiities between the Member States, it is essential to ensure that the deelopment o serice actiities

contributes to the ulilment o the task laid down in Article 2 o the 1reaty o promoting . the raising

o the standard o liing and quality o lie and economic and social cohesion and solidarity among the

Member States`.

104

1he ourth Recital adds that the remoal o legal barriers to the establishment o a

genuine internal market, while ensuring an adanced Luropean social model, is thus a basic condition

or oercoming the diiculties encountered in implementing the Lisbon strategy and or reiing the

Luropean economy, particularly in terms o employment and inestment`.

105

It continues that |i|t is

thereore important to achiee an internal market or serices, with the right balance between market

opening and presering public serices and social and consumer rights.`

106

O course, the Directie does

not gie a deinition o what is meant by the Luropean Social Model`.

10

But the use o the term sends

out the necessary political message.

1here are also a number o other reerences in the Preamble to labour law, indicating that

labour law enjoys particular protection in a way that other interests are not. lor example, bolted on to

102

http://register.consilium.europa.eu/pdf/en/06/st10/st10003.en06.pdf.

103

Art. 45.

104

Amendment 1, Recital 1 of the EP First Reading Report A6-0409/2005. See also 71

st

Recital The mutual evaluation

process should not affect the freedom of the Member States to set in their legislation a high level of the protection of the

public interest, in particular in relation to social policy objectives.

105

Amendment 3 of the EP First Reading Report A6-0409/2005.

106

Ibid.

107

Various definitions have been offered elsewhere: see e.g. Nice European Council 2000 (para. 12) The European

social model has developed over the last forty years through a substantial Community acquis It now includes

essential texts in numerous areas: free movement of workers, gender equality at work, health and safety of workers,

working and employment conditions and, more recently, the fight against all forms of discrimination.

20

the end o the 8

th

Recital - a proision which primarily concerns the regulatory techniques to achiee an

internal market in serices - is the sentence that |t|his Directie also takes into account other general

interest objecties, including the protection o the enironment, public security and public health, as

well as the need to comply with labour law.` 1he 13

th

Recital adds that |i|t is equally important that this

Directie ully respect Community initiaties based on Article 13 o the 1reaty with a iew to

achieing the objecties o Article 136 thereo concerning the promotion o employment and improed

liing and working conditions`.

108

,ii, Lxclusion rom scope: Articles 1,6, and 1,,

1he L1UC`s greatest ictory was the adoption o Articles 1,6, and 1,, aimed at excluding labour law

and undamental rights rom the scope o the Serices Directie. As we shall see, the L1UC`s ootprint

on these proisions is ery clear.

;a) 1be rori.iov. ava tbeir origiv.

Article 1,6, proides:

1his Directie does not aect labour law, that is any legal or contractual proision concerning

employment conditions, working conditions, including health and saety at work and the

relationship between employers and workers, which Member States apply in accordance with

national law which respects Community law. Lqually, this Directie does not aect the social

security legislation o the Member States.

109

1he inal ersion ollows almost exactly the reised wording put orward by the L1UC to the

Parliament.

110

1he 14

th

Recital clariies what is meant by employment conditions and working

conditions:

1his Directie does not aect terms and conditions o employment, including maximum work

periods and minimum rest periods, minimum paid annual holidays, minimum rates o pay as

well as health, saety and hygiene at work, which Member States apply in compliance with

Community law, nor does it aect relations between social partners, including the right to

negotiate and conclude collectie agreements, the right to strike and to take industrial action in

accordance with national law and practices which respect Community law, nor does it apply to

serices proided by temporary work agencies. 1his Directie does not aect Member States`

social security legislation.

111

108

Amendment 8, of the EP First Reading Report A6-0409/2005.This originally formed part of what became the 14

th

Recital. See also Article 16(4) provides: By 28 December 2011 the Commission shall, after consultation of the

Member States and the social partners at Community level, submit to the European Parliament and the Council a report

on the application of this Article, in which it shall consider the need to propose harmonisation measures regarding

service activities covered by this Directive.

109

Emphasis added. In the absence of a Community definition of labour law, the Directive tries to provide some

guidance. The protection of discrimination law is mentioned only in the Preamble: 11

th

Recital. Further detail as to what

constitutes terms and conditions of employment can be found in the 13th and, more specifically, the 14

th

Recital. The

14

th

Recital explicitly identifies the right to strike and to take industrial action in accordance with national law and

practices which respect Community law.

110

Revisions to Art. 1(4), ETUC 20 Jan. 2006. The second sentence of this draft formed the basis for what is now Art.

1(7).

111

The 11

th

Recital adds that The Directive does not affect Member State laws prohibiting discrimination on the

grounds of nationality or on grounds such as those set out in Article 13 of the Treaty.

21

1his recital closely relects the L1UC`s proposed reised drat o what was originally Article 1,4, o the

Directie, now Article 1,6,.

112

Article 1,, deals speciically with undamental rights. It says that t|his Directie does not aect

the exercise o undamental rights as recognised in the Member States and by Community law. Nor

does it aect the right to negotiate, conclude and enorce collectie agreements and to take industrial

action in accordance with national law and practices which respect Community law.`

113

1he second sentence o Article 1,, again relects the L1UC`s proposals to the Luropean

Parliament, although reerence to extending collectie agreements has been dropped. loweer, the act

that the Directie expressly makes clear that the Directie does not aect the right to negotiate,

conclude and enorce collectie agreements` helps to address trade union concerns about the

obseration made by the Commission in its 2002 reiew o barriers to the internal market in serices

114

that collectie agreements constituted one such barrier to serice proision.

1his point is urther addressed by Article 4,, which deines the meaning o requirements`. I

the rule is a requirement` it is subject to challenge under the Directie. 1he word requirement` is

broadly construed to include, or example, any obligation, prohibition, condition or limit proided or

in the laws, regulations or administratie proisions o the Member States. loweer, the Article

concludes with the statement that rules laid down in collectie agreements negotiated by the social

partners shall not as such be seen as requirements within the meaning o this Directie`.

115

lor good

measure, Article 14,6, also excludes consultation o organisations, such as . social partners, on

matters other than indiidual applications or authorisations` rom the list o prohibited requirements in

Article 14.

1he L1UC`s ersion o Article 1,, was modelled on the undamental rights clause in so-called

Monti Regulation 269,98.

116

loweer, the inal ersion o Article 1,, is actually narrower in scope

than its Monti orbear. In particular, it omits reerence to the right` to strike, reerring only to industrial

action, although it does suggest that this might be a right. loweer, reerence to the rigbt to strike`

11

appears in the 14

th

Recital: |t|he Directie does not aect . the rigbt to .tri/e ava to ta/e ivav.triat actiov

in accordance with national law and practices which respect Community law.` 1he 15

th

Recital adds:

1he Directie respects the exercise o undamental rights applicable to the Member States and

as recognised in the Charter o undamental rights o the Luropean Union and the

112

ETUC 20 Jan 2006.

113

See also the 15

th

Recital which expressly refers to the Charter and the accompanying explanations.

114

COM (2002) 441, 50.

115

Following Amendment 90 of the EP First Reading Report A6-0409/2005.

116

OJ 1998 L337/8. Art. 2 provided This Regulation may not be interpreted as affecting in any way the exercise of

fundamental rights, as recognised in Member States, including the right or freedom to strike. These rights may also

include the right or freedom to take other actions covered by the specific industrial relations systems in Member States.

117

See also Viking, para. 44 the right to take collective action, including the right to strike, must therefore be regarded

as a fundamental right which forms an integral part of the general principles of Community law.

22

accompanying explanations, reconciling them with the undamental reedoms laid down in

Articles 43 and 49 o the 1reaty. 1hose undamental rights include the rigbt to ta/e ivav.triat

actiov in accordance with national law and practices which respect Community law.

1he reerence to the need to reconcile the exercise o undamental rights with the undamental

reedoms laid down in Articles 43 and 49 o the 1reaty` became prophetic in the light o the decisions

in 1i/ivg and arat. lor this reason, the L1UC had objected to the use o such language since the text

seems to suggest that undamental rights and market reedoms are o equal alue and should be

balanced with each other`.

118

1he L1UC lost on this point and, as we hae seen, the union moement

largely lost the point again beore the LCJ in 1i/ivg and arat.

1here is a urther point to note too. Under Article 1,, a right to take industrial action is only a

legitimate exception to the reedom to proide serices insoar as this is consistent with Community

law.

119

1his opens up the possibility that industrial action which the Court deems inconsistent with

Community law - such as the situation identiied in 1i/ivg where strike action is taken een though no

jobs are jeopardised or under serious threat`

120

- will be coered by the Serices Directie ,and Article

49

121

,.

;b) 1be tegat effect of .rticte. 1;) ava 1;)

1he legal eect o the language does not aect` used in both Articles 1,6, and 1,, is not clear. Do

they operate as total exclusions, like the sectors excluded in Article 2 ,in which case why are they in a

separate Article,, or do these proisions hae less legal orce than the exclusions in Article 2, due to

the weaker language ,does not aect`,, with the result that they are merely declaratory and aspirational

1he lrench language ersion obuscates still urther because it uses yet urther terminology. Article 1,6,

says La prsente directie ve .`atiqve a. au droit du traail` and Article 1,, La prsente directie

v`affecte a. l`exercice des droits ondamentaux`. I would argue these proisions operate, in practice, as

total exclusions and thus hae the same weight as the Article 2 exclusions. 1his may be or political

rather than legal reasons. Various politicians hae argued that the deliberately wide drating o Article

1,6, was intended to make sure that the Directie is labour law neutral`,

122

a point conirmed by

Commissioner McCreey beore the Luropean Parliament:

123

1he Commission wants to state unambiguously that the Serices Directie does indeed not

aect labour law laid down in national legislation and established practices in the Member

States and that it does not aect collectie rights which the social partners enjoy according to

national legislation and practices.

118

ETUCs amendments submitted to the Commission when the Commission was putting forward its revised proposal.

119

See also the similar drafting in Art. 28 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights 2000.

120

Para. 84.

121

See also Viking, para. 44 the right to strike may be subject to certain restrictions. As is reaffirmed by Article 28 of

the Charter those rights are to be protected in accordance with Community law and national law.

122

Evidence given by Rt Hon Ian McCartney to the House of Lords EU Select Committee on 17 May 2006, annexed to

the House of Lords EU Select Committee 38

th

Report 2005-6, p.23.

123

SPEEC/06/687, European Parliament Plenary Session, Strasbourg, 15 Nov. 2006.

23

1hus, een i the exclusions in Article 1,6,-,, were originally intended to hae a soter`, descriptie

orm than those in Article 2, they may well assume a harder edge through interpretation, gien the

sensitiities surrounding the sectors and actiities, o which the draters ,and ultimately the Court, are

well aware.

So, what then is the eect o Articles 1,6, and 1,, 1hey would seem to rule out direct

challenges under the Serices Directie to national labour law based on a broad market access reading

o barriers or requirements. So, or example, they would rule out challenges by a serice proider

employing local sta ,situations 2.2-2.4 and 3.2-3.3 in table 1 aboe, rom arguing that haing to

comply with the employment laws o the host state in respect o those sta intereres with the serice

proider`s market access. In addition, Article 1,6, may rule out any challenges by a serice proiding

company that host state employment laws are being applied to its posted sta aboe the minima laid

down by the Posted \orkers` Directie ,situation 3.4 in table 1 aboe,.

Article 1,6, and ,, also appear to rule out challenges to the existence o collectie agreements

which might goern the terms and conditions o such sta on the grounds that the collectie

agreements interere with the proision o serices. Likewise, the act that strike action intereres with a

serice proider`s proision o serices will also not be challengeable under the Serices Directie so

long as those strikes are compatible with national law and practice and Community law. loweer, as

the 1i/ivg and arat cases make clear, barriers created by national employment laws - een i exempted

rom the Directie - may neertheless be caught by Articles 43 and 49 o the LC 1reaty unless those

rules can be justiied and the steps taken are proportionate.

loweer, Article 1,6, o the Directie will hae little impact on the truly sel-employed wishing

to establish themseles or to proide serices ,situations 2.1 and 3.1 in table 1 aboe,. 1his is due to the

act that, as sel-employed, national employment laws are unlikely to apply anyway.

124

\et, much

depends on the deinition o sel-employed. Some states take a tough line on determining who is, in

reality, a dependent worker irrespectie o how they describe themseles. Len the Court o Justice has,

on occasion, been prepared to look at the reality o the situation.

125

1he L1UC hoped that a deinition

o worker might be included in the deinition section in Article 4. 1hey were unsuccessul but a

proision was inserted in the Preamble that it is or the bo.t Member States to determine the existence

o an employment relationship and the distinction between sel-employed persons and employed

persons, including alse sel-employed persons`.

126

Somewhat oddly, gien that the Directie says that

the deinition is a matter or vatiovat law, the Recital then repeats the classic Covvvvit, deinition o a

124

Cf Reg 1408/71 (OJ 1971 L149/2).

125

Case C-256/01 Allonby v Accrington & Rosendale College [2004] ECR I-8349.

126

87

th

Recital. See also the Commissions Green Paper Modernising Labour Law to meet the challenges of the 21

st

century: COM (2006) 708 which considers further the question of false self-employment. National courts have been

doing this for some time: see eg in the UK context Lane v Shire Roofing [1995] IRLR 493.

24

worker.

12

Is this a hint that Member States should coalesce in their own systems around the

Community deinition o worker 1hat said, gien that it is anticipated that the Serices Directie will

be o particular help to small serice proiders, the act that the majority o serice proiders are sel-

employed will dilute the impact o Article 1,6,.

;c) ]v.tificatiov.

As we hae seen, Articles 1,6, and 1,, aimed at protecting national employment laws rom being

challenged as incompatible with the Serices Directie. \e turn now to national rules which would not

necessarily all in the Article 1,6, or 1,, exclusion, since they do not directly concern labour law as

deined in Recital 14, but neertheless sere a justiiable social purpose. In other words, we are now

examining national rules with an indirect eect on social policy or employment law.

In order to coer this situation, social policy objecties` were included as a justiication in

Article 4,8,. 1hese justiications, which can be inoked by Member States to justiy restrictions on