Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

History of ET Essay JSTIEDA

Încărcat de

jstieda6331Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

History of ET Essay JSTIEDA

Încărcat de

jstieda6331Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Educational Technology

Past Practice and Pedagogy inform the Present and Future

(Fun with Dick and Jane)

By Jennifer Stieda Education has a long history of building upon past practices and technologies, always with a view to improving the future. Beginning with the Sophists in the 5th century, whose contribution to educational technology was group discussion and expository lectures, the teaching profession has incorporated the best of the past and moved on. Pierre Abelards 11th century methods laid the foundation for St. Thomas Aquinas Scholastic Method which subsequently gave rise to the university system in Europe. One hundred years after the introduction of the printing press, John Amos Comenius was able to exploit that technology to educational advantage by advocating the use of books which specifically organized subject matter into an optimal learning sequence. Following that momentous innovation, Joseph Lancaster furthered inexpensive education of the masses in the 19th century through his monitorial system which included large classes and basic instructional media such as blackboards, slates and charts (Caplan, 1998; Saettler, 1968). In the 20th century, educational technology made leaps and bounds adding a plethora of so-called magic bullets to the arsenal of education including the magic lantern, film, radio, TV, computers and the Internet. Many of these technologies did not live up to their optimistic claims. However, they have all contributed to furthering improvements to the methodologies and technologies used in education currently. A review of the literature on the history of educational technology finds several recurring issues including (1) what an optimal learning environment looks like, (2) what the roles of the teacher and student are, (3) what it is that students need to learn, and (4) where educational technology dollars should be invested. Over time the answers have changed, but in general, the questions remain constant. Educational technology has changed dramatically over the last 100 years and people have consistently looked to the latest technologies to solve the educational problems of the day. When the use of technology is seen as more important than merely the technology itself, the answers to the four recurring problems change. In this essay, I will explore the use of technology and the ways that attention to this radically alters the answers to the four problems posed above.

The Learning Environment

(See Dick and Jane at School)

Many contend that classrooms have not changed substantially in the last century (Hooper, 2008; Petrina, 2002; Puryear, 1999). They are right in some ways. In classrooms all over the world, there are desks for students, the ubiquitous re-writable wall-mounted board (black, green or white), textbooks, one teacher and a group of students assembled in a room in a building called a school. However, the biggest changes in schools have not been to the physical space, but to the mental space. What has really changed is atmosphere. Classroom culture has changed concurrently with pedagogy. There has been a shift from individual work to group work, mining knowledge in textbooks to active knowledge construction on the net, direct instruction to project-based peer collaborated instruction.

Very little furniture was moved, but the alteration has been profound. Teachers have never had so many strategies available to tempt students to the threshold of learning. Another major change in the classroom can be seen in the increasing number of tools available for learning and how they are used. In the early to mid-twentieth century, North America was obsessed with building bigger, better widgets the faster, the better. If production lines worked for industry, why not try it for education? Technology was touted as the cure for the ills of high costs and high enrolment due to the post-war baby boom. The result was a progression of educational technology including selfhelp workbooks, movies, teaching machines and computers (Petrina, 2002; Ely, 2008). Often these tools were used to replace teachers by mimicking methods already in place. Most of these tools did not live up to their unrealistic expectations. Children are not commodities and schools are not factories after all. Educating people is more complex than manufacturing soap because the product to be moulded is human (Rotherham & Willingham, 2009). The increase in the use of technology in the classroom has been accompanied by an increase in the use of that technology by students. This has extended the application of technology beyond replicating direct instruction-type classroom activities. Technology itself has never been able to transform learning (Byrne, 2009), but it can act as a powerfully engaging tool that students can use in the creation of their own understanding. As Jaron Lanier (2008) said, "We already knew that kids learned computer technology more easily than adults. What we're seeing now is that they don't even need to be taught. It is as if children were waiting all these centuries for someone to invent their native language." Students know that technology is everywhere (Allen, 2008). They use it and learn new applications at an amazing, some might say alarming, rate. This explosion of technology in the past ten years has happened too fast for schools and teachers to keep pace (Allen, 2008; Mishra et al., 2009). The future keeps rolling out with ever more technology to astonish us despite persistent resistance. We need to intelligently select from our quiver of pedagogy to intelligently release the enormous potential for technology in education (Maddux, 2005; Puryear, 1999). An example of this potential can be seen in the way online learning has transformed distance education. It makes learning available almost anytime, anywhere, to anyone and for any purpose. Distance education has always meant the classroom could be in an office cubicle or at the kitchen table. However, the Internet has moved the learning environment one step further into the virtual world. Changes over the last century in pedagogy and technology have made learning at a distance more collaborative and less isolated. Another way that technology has made learning less isolated is through assistive technology for students with physical or mental disabilities. Assistive technology has made meaningful participation in the classroom a reality. In the past, these students were either marginalized or absent entirely. For many of these people, the classroom has changed significantly.

The Roles of Teachers and Students

(Look! See Jane Teach!)

There has been a gradual shift from teacher-centred activity to student-centred activity in education over the past 100 years (Betrus & Molenda, 2002; Gourley, 2010). Along with this shift in pedagogy came technological advances which now make it possible for teachers to put students in the drivers seat more often. In the first half of the 20th century, Behaviourism was matched with linear forms of media such as specially designed workbooks, radio, film and TV. Cognitivism accompanied the personal

computer from the 1960s to the 1980s. From the 1990s to today, Constructivism is complemented by networks of information sharing on mobile devices (Shepherd, 2007; Whelan, 2005). With each theory came a further shift toward student-centred learning. Students now have an unprecedented level of power over their learning both in terms of content and environment at least in theory. Educational institutions are slow to change and implementing constructivism comes with new challenges for teachers both in the classroom and online. As a result of this dual-layered shift, the role of the teacher has been modified significantly. Direct instruction was the prevailing teaching method for formal education for centuries until the late 1990s. With the advent of constructivism, teachers spend more time facilitating and guiding learners toward curricular goals. Teachers are expected to be technologically literate and maintain this literacy in an ever-changing technologically driven world (Whelan, 2005). The current teacher is on the cusp of yet another transformation into the experienced learner (Richardson, 2009) where the learners interests lead the learner and teacher into areas of mutual unknown. Thus, the teacher has morphed from sage on the stage, to guide on the side, to vet on the net. Throughout this career makeover, there have always been inspiring teachers who take on their role in a way that motivates their students to best performance. (Krause, 2003; Moody, 1999) Some teachers have managed to make learning captivating by making it relevant no matter what technologies were available to them. Because young people are digital natives, technology has the potential to make learning both captivating and relevant. However, the power and potential of educational technology must be acknowledged to reside within the educators and not within objects (Mishra et al., 2009). So, the question is not what technologies will engage learners best which is often what we have asked. The question is how can we produce more of these outstanding teachers who know how to use technology effectively? (Puryear, 1999) In some cases, finding excellent teachers is simply not possible. One problem facing developing countries is a lack of teachers, never mind brilliant ones. People are not interested in moving to slums or remote villages, for example, to teach in unfamiliar and uncomfortable surroundings. Sugata Mitra (2010) has found what he thinks may be a viable solution for socially or geographically isolated areas. In his Hole in the Wall experiments, teachers have been replaced almost entirely by computers and the Internet. Children teach themselves, motivated by natural curiosity something teachers are always trying to tap into. In some of his experiments, an adult successfully assisted children to learn online by using the grandmother method; encourage, ask questions, and admire but not teach. Another initiative related to putting computers in the hands of underprivileged children is the One Laptop per Child Project (Negropont, 2006). This group has developed a cheap, Internet-enabled, pedal-powered computer intended for distribution to developing nations. By integrating these two schemes, technology may be able to solve a dilemma for the disadvantaged through reinventing the roles of the teacher and student. An essential change in the future of teaching is toward purposeful collaboration. Teachers in the past often worked in isolation. Asking for help was construed as a weakness and offering help to those less senior, as arrogance. Despite that, sharing among teachers has been a common practice for the last couple of decades with professional development days organized at the school or district level. The next logical step is toward co-teaching among teachers, parents, experts in the community and students. The Internet has provided an unprecedented opportunity for people to collaborate. As Gourley (2010) suggests, We see on the web people from all over the world creating communities of interest (some of them very sophisticated indeed) on a whole range of subject matter not dictated by academics. We

need to ask ourselves how we can tap into this energy and recognize the learning. Some believe that digital natives moving into the teaching profession will undoubtedly generate more creative uses for these opportunities than their predecessors.

What Students Need to Know

(Learn, Dick, Learn!)

Jane Austen (1813) wrote that to be truly accomplished, A woman must have a thorough knowledge of music, singing, drawing, dancing, and the modern languages, to deserve the word; and besides all this, she must possess a certain something in her air and manner of walking, the tone of her voice, her address and expressions, or the word will be but half deserved. Todays accomplished person (for we can no longer set women apart in their education) must have a thorough skill set for critical thinking, collaborative problem solving, relationship building, creative design and composition, information literacy and intercultural understanding along with wide-ranging knowledge to back it all up (Ehrmann, 2002; Richardson, 2009; Rotherham & Willingham, 2009; U.S. Department of Education, 2010). In addition, learners today no longer need to be wealthy to pursue these accomplishments as was essential in Jane Austens time. There is much debate over whether students need to build knowledge or learn skills (Byrne, 2009; Ehrmann, 2002; Fletcher, 2006; Richardson, 2009; Rotherham & Willingham, 2009). Some believe that domain knowledge is only important as a backdrop for learning skills. Others think skills and knowledge are inseparable and should be taught with equal weight in order to prosper into the future. Ultimately, decisions about what students need to learn must be based on sound research (Maddux, 2005; Rotherham & Willingham, 2009). The reality for teachers is that what students need to learn has largely been legislated for implementation and reflects the social and political background of the time (Petrina, 2002). For example, after the launch of Sputnik by the Russians, the American government reacted by passing the National Defence Education Act in 1958 (Betrus & Molenda, 2002; Crapo et al., 2008). It was aimed at enhancing higher education mainly in the areas of science, mathematics, and modern foreign languages. In 2001, the No Child Left Behind Act resulted in an emphasis on standardized testing. It was intended to make schools accountable for their results. However, it has led to various problems including teaching to the test through superficial rote learning and not pursuing deeper understandings which can be transferred to practical applications (Allen, 2008; Shattuck, 2007). Most recently, the ambitious National Educational Technology Plan 2010 (NETP) was unveiled in the United States (U.S. Department of Education, 2010). It asks the question: What's worth knowing and being able to do? and answers, in part, by stating a need for developing deep understanding within specific domains and learning the same technology that is used in the workplace. The plan calls for reformation of content standards and learning objectives to reflect tomorrows technological and social reality. It also suggests radical change in the way education is delivered including the use of technology. However, it will likely be some time before this becomes the norm. Using the Internet as an educational tool has resulted in some new learning goals. Richardson (2009) states that our students are going to be Googled or searched for online, over and over and over in their lives...if we dont teach our kids how to create and manage their own lifestreams online, someone else may create those footprints for them. Safe and thoughtful use of social media is a critical skill in todays world. The new NETP places some emphasis on ethical participation in the context of global

networks. Although teaching ethics in school is probably not new, the Internet has given this concept a new and highly relevant twist.

Investing in Educational Technology

(See Dick and Jane Spend)

Research has shown that spending money on technology alone doesnt guarantee great educational results (Allen, 2008; Puryear, 1999). Yet one of the biggest mistakes repeated over the last 100 years has been surrendering to the rapture of technology (Ehrmann, 2002). It is somewhat ironic that the field of education does not always learn from its own mistakes. However, we have learned to replace the magic bullet mentality with realistic (and futuristic) expectations for technology. All the money invested in educational film, radio and TV into the 1970s had little noticeable effect on learning outcomes (Whelan, 2005). In the 1980s and 1990s, there was a great deal of excitement about, and therefore money spent, getting computers into schools (Maddux, 2005). People knew that computers were becoming essential tools in the workplace so it made sense to teach children how to use them. However, in some cases, little thought was put into the process. A litany of errors resulted including building new schools without computer labs, having no long-range plan or worse, not following it, paying the price for taking the lowest contract bid, omitting teacher training, forgetting to budget for maintenance or software, thinking of technology as a panacea, introducing technology without pedagogy, and falling prey to political whims or corporate marketing (Ehrman, 2002; Hooper, 2008; Keller, 2000; Orlich, 1989; Petrina, 2002). However, not all money was spent in vain. Kate Moody (1999) describes a high school success story of the 1960s and 1970s where television was used in a highly successful educational manner. Others have described similar, but more recent triumphs such as Urban Academy High School (Krause, 2003) or those described on edutopia.orgs Schools that Work webpage. The effective schools movement beginning in the 1960s tried to capture the learnings from places like these (Mace-Matluck, 1987). Many of the hallmarks of an effective school outlined by that movement are applicable today. The difficulty is in making them a reality. This practical aspect of implementation is in the hands of teachers and administrators. People, not words on paper and perhaps not even that much money, are required to make the difference. Effective use of limited budgets is part of attributing success to schools. Technology in education and the availability of money have always danced a passionate pas de deux. The cost of technology is in constant motion. As new technology becomes available, the old becomes more affordable but possibly out-of-date at the same time. Not all the latest tools are educationally worthy, either. There is a need to ensure good decisions are made through good planning and implementation. Collaboration and joint discussions on needs and solutions, can make this is possible (Keller, 2000). As the more tech savvy digital natives move into the teaching profession, more intelligent decisions will hopefully be made. One way to take advantage of what has been learned in the past is through research. Maddux (2005) believes that many poor decisions can be traced to a widespread lack of belief in the importance of educational research. Meaningful educational reform can only come from relevant research and development with practical implications for teaching practice. Research is needed on the effectiveness of the use of technology which is based on pedagogical best practices. As stated by Rotherham and Willingham (2009), Why mount a national effort to change education if you have no way of knowing whether the change has been effective? The downside to this approach is that research takes time,

and with the proliferation of new technologies escalating at a near-exponential rate, time is not a luxury that can be afforded. Teacher education is another area in which to seek solutions. Preparing exceptional teachers who know how to use technology to its best advantage for learning is critical for future learners. This kind of preparation can take the fear out of the technological unknown. No matter what century you look at, acceptance of new technology was difficult. For example, Socrates felt that writing would undermine the then-current oral tradition of learning (Norman, 2010). Despite fear, change comes about anyway because every generation of new teachers arrives on the doorstep full of energy and passion for whatever is new and better. The next wave of digital native teachers will embrace all the potential of the social nature of technology and education. Bridging the digital divide is another important area for investment. Initiatives like Negroponts One Laptop per Child are making strides in this direction for developing nations. Keeping schools stocked with state-of-the-art technology will level the playing field for disadvantaged students all over the world. However, it is one thing to spout the rhetoric of educational reform as in the NETP and quite another to deliver it. The reality is that budgets are tight and educational institutions will never keep pace with changing technology (Puryear, 1999; Rotherham & Willingham, 2009).

The Future Looks Bright

(See Dick and Jane wearing shades!)

Learning environments will continue to be transformed over time as change inexorably makes its progress through our world. Work has already begun towards realizing constructivist learning environments based on pedagogically sound practice. The NETP (2010) touts an example of this in its exciting School of One pilot project. Digital technology will play a significant role in future learning environments. The roles of teacher and student are well on the way to being altered forever. Both roles will require a fluid grounding in a perpetually changing digital world. Students will take more responsibility for their own learning and that of their peers. As a result, teacher education is one area for future investment, as is bridging the digital divide across the globe through the availability of up-to-date technological tools. Technology alone will not produce good educational results. The modern accomplished person needs a solid foundation of knowledge coupled with skills for the 21st century. The past informs the way forward. Learning is always fraught with error, but if the errors are used to benefit the future, all is not lost. There is an enormous challenge ahead in terms of the rate of change the world is about to experience. However, with the growing number of digital screens lighting up the globe, the future of educational technology looks bright indeed.

Works Cited

Allen, L. (2008). The Technology Implications of a Nation at Risk. Phi Delta Kappan , 89 (8), 608-610. Austen, J. (1813). Pride and Prejudice. (2003 ed.). New York, NY: Bantam Dell.

Betrus, A.K. & Molenda, M. (2002). Historical Evolution of Instructional Technology in Teacher Education Programs. TechTrends , 46 (5), 18-21, 33. Retrieved October 27, 2010, from http://www.springerlink.com/content/r12636968527w137/ Byrne, R. (2009). The Effect of Web 2.0 on Teaching and Learning. Teacher Librarian , 37 (2), 50, 52-53. Retrieved October 27, 2010, from CBCA Education. (Document ID: 1938481361). http://proquest.umi.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/pqdweb?index=1&did=1938481361&SrchMode=1&sid= 7&Fmt=6&VInst=PROD&VType=PQD&RQT=309&VName=PQD&TS=1288155562&clientId=6993 Caplan, D. (1998). The Invisible People: Educational Technologists - Do We Exist? Retrieved from http://www.usask.ca/education/coursework/802papers/caplan/caplan.PDF, 1-10. Crapo, C., Lea, G., Lindemann, B. & Nichols, G. (2008). Introduction to the Field of Instructional Design and Technology. Retrieved November 1, 2010 from http://www.gingernichols.com/wpcontent/uploads/InductionExerciseCrapoLeaLindemannNichols.pdf Ehrmann, S.C. (2002, Jan/Feb). Improving the Outcomes of Education: Learning from Past Mistakes. Educause Review , 54-55. Retrieved October 15, 2010 from http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/erm0208.pdf Ely, D. (2008). Frameworks of Educational Technology. British Journal of Educational Technology , 39 (2), 244-250. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2008.00810.x Fletcher, G.H. (2005) Why Arent Dollars Following Need? The Need for Professional development is Enormous and Expressed; the Questions Is, Wheres the Money? T.H.E. Journal, 32 (2), 4. Gourley, B. (2010). Dancing with History: A Cautionary Tale. Educause Review , 45 (1), 30-41. Retrieved from http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ERM1012.pdf Hooper, R. (2008). Educational Technology - a Long Look Back. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39 (2), 234-236. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2008.00813.x Keller, J. (2000). Learning From Our Mistakes. Technology & Learning , 20 (11), 60-66. Retrieved October 15, 2010 from http://global.factiva.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ha/default.aspx Krause, S.D. (2010). The Flickering Mind: A Review. [Review of the book The Flickering Mind: The False Promise of Technology in the Classroom, by Todd Oppenheimer]. Retrieved November 11, 2010 from http://www.bgsu.edu/cconline/reviews/krause_review.html Lanier, Jaron quoted in Davis, L.B. (2008, August 22). Our Favourite Quotes [Web log message]. Retrieved from http://edtechpower.blogspot.com/2008/08/our-favorite-quotes.html Mace-Matluck, B. (1987) The Effective Schools Movement: Its History and Context. An SEDL Monograph. Retrieved November 11, 2010 from http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED304781.pdf Maddux, C. (2005). Information Technology in U.S. Education: Our Mistakes and How to Avoid Them. International Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning , 1 (1), 19-24. Retrieved October 15, 2010 from http://www.sicet.org/journals/ijttl/issue0501/MadduxVol1.Iss1.pp19-24.pdf

Moody, K. (1999). The Children of Telstar: Early Experiments in School Television Production. New York, NY: Vantage Press. Custom course materials ETEC 512. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia, Bookstore. Mishra, P., Koehler, M.J. & Kereluik, K. (2009). The Song Remains the Same: Looking Back to the Future of Educational Technology. TechTrends , 53 (5), 48-53. Retrieved October 15, 2010 from http://www.springerlink.com/content/3011317p14586j15/ Mitra, Sugata. (2010, September). The Child-driven Education [video file]. Retrieved October 15, 2010 from http://www.ted.com/talks/sugata_mitra_the_child_driven_education.html Negropont, N. (2006, August). One Laptop per Child [video file]. Retrieved November 1, 2010 from http://www.ted.com/talks/nicholas_negroponte_on_one_laptop_per_child.html Norman, J. (2010). From Cave Paintings to the Internet: a Chronological and Thematic Database on the History of Information and Media. Retrieved November 20, 2010 from http://www.historyofscience.com/G2I/timeline/index.php?category=Communication Orlich, D. C. (1989). Education Reforms: Mistakes, Misconceptions, Miscues. Phi Delta Kappan , 70 (7), 512-517. Retrieved October 25, 2010 from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20403951 Petrina, S. (2002). Getting a Purchase on "The School of Tomorrow" and its Constituent Commodities: Histories and Historiographies of Technologies. History of Education Quarterly , 42 (1), 75-111. Retrieved October 20, 2010 from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3218168. Puryear, J. M. (1999). The Economics of Educational Technology. Custom course materials ETEC 511. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Okanagan, Bookstore. (Reprinted from TechKnowLogia (September/October), 46-49.) Richardson, W. (2009). Why Schools Should Break the Web 2.0 Barrier. Threshold , Summer, 8-10. Retrieved October 20, 2010 from http://www.bcelc.ca/pages/personalizedlearning/Web20_in_Schools.pdf Rotherham, A.J. & Willingham, D. (2009). 21st Century Skills: The Challenges Ahead. Educational Leadership , Sep, 16-21. Retrieved October 20, 2010 from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/sept09/vol67/num01/21st-Century-Skills@The-Challenges-Ahead.aspx Saettler, P., (1968). A History of Instructional Technology (pp 11-35). New York: McGraw-Hill. Retrieved from Instructional Technology/History Pre 1900 http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Instructional_Technology/History_Pre1900 Shattuck, G. (2007). The Historical Development of Instructional Technology Integration in K-12 Education. Retrieved from http://www.nowhereroad.com/technology_integration/readings/shattuck.pdf

Shephard, C. (2010). A Brief History of Instructional Technology and the Ideas Affecting It. Retrieved October 20, 2010 from http://projects.coe.uga.edu/ITFoundations/index.php?title=A_Brief_History_of_Instructional_Technolog y_and_the_Ideas_Affecting_It U.S. Department of Education. (2010). National Educational Technology Plan 2010: Transforming American Education: Learning Powered by Technology. Retrieved November 1, 2010 from http://www.ed.gov/technology/netp-2010 Whelan, R. (2005). A Look at Past, Present & Future Trends. Connect: Information Technology at NYU, Spring/Summer, 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.nyu.edu/its/pubs/connect/spring05/pdfs/whelan_it_history.pdf Wikipedia. (2010). No Child Left Behind Act. Retrieved November 3, 2010 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No_Child_Left_Behind_Act

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- ADocument11 paginiAjstieda6331Încă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5795)

- KTEA II ReportDocument4 paginiKTEA II Reportjstieda633150% (2)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- EPSE 410: Scenario Implementation Assignment: (Case Study #1)Document7 paginiEPSE 410: Scenario Implementation Assignment: (Case Study #1)jstieda6331Încă nu există evaluări

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Discussion Forum Participation: Research Proposal Jennifer A. Stieda University of British ColumbiaDocument10 paginiDiscussion Forum Participation: Research Proposal Jennifer A. Stieda University of British Columbiajstieda6331Încă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- 510 Final Design ProposalDocument12 pagini510 Final Design Proposaljstieda6331Încă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Micro Project: Vivekanand Education Society PolytechnicDocument15 paginiMicro Project: Vivekanand Education Society PolytechnicMovith CrastoÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Relation Between ICT and DiplomacyDocument7 paginiRelation Between ICT and DiplomacyTony Young100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Testing and Beyond - Strategies and Tools For Evaluating and Assessing Infants and ToddlersDocument25 paginiTesting and Beyond - Strategies and Tools For Evaluating and Assessing Infants and ToddlersMargareta Salsah BeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- States That Do Not Require The CGFNSDocument1 paginăStates That Do Not Require The CGFNSDevy Marie Fregil Carrera100% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- RESUME DineshDocument2 paginiRESUME DineshRaj KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- American Accounting Association (AAA) : Presented BY: Ernie Anderson Lyngdoh Robert W. KharngiDocument16 paginiAmerican Accounting Association (AAA) : Presented BY: Ernie Anderson Lyngdoh Robert W. KharngiD MÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- British Education SystemDocument12 paginiBritish Education SystemAnastasija KursukaiteÎncă nu există evaluări

- 307K Rehabilitation of Criminals & JuvenilesDocument81 pagini307K Rehabilitation of Criminals & Juvenilesbhatt.net.in75% (4)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- P2 Specimen Paper (QP) PDFDocument30 paginiP2 Specimen Paper (QP) PDFBryan Yeoh100% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- 7em SocDocument226 pagini7em Socvenkat_nsnÎncă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- Assignment 1 ,,, Significance of ESDDocument7 paginiAssignment 1 ,,, Significance of ESDNayab Amjad Nayab AmjadÎncă nu există evaluări

- ECPE Writing Rating ScaleDocument1 paginăECPE Writing Rating ScaleJenny's JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Accepted TestsDocument1 paginăAccepted TestsDuma DumaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- اختلاف اخباریون و اصولیون شیعهDocument31 paginiاختلاف اخباریون و اصولیون شیعهhamaidataeiÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Khaleb Straight - The Byzantine Empire Russia and Eastern Europe Unit - FinalDocument170 paginiKhaleb Straight - The Byzantine Empire Russia and Eastern Europe Unit - Finalapi-269480354100% (1)

- Impact of ICT in ANFE in Nigeria - A ReviewDocument10 paginiImpact of ICT in ANFE in Nigeria - A ReviewMuhammad Muhammad SuleimanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Executive Post Graduate Programme in Management: For Working Professionals Batch 13Document18 paginiExecutive Post Graduate Programme in Management: For Working Professionals Batch 13Vakul KhullarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clinical Field Experience A-InterviewDocument5 paginiClinical Field Experience A-Interviewapi-548611213Încă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Mental Status ExamDocument44 paginiMental Status ExamHershey Cordero Briones100% (1)

- HR MCQDocument22 paginiHR MCQASHWINI SINHAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Method of Wage DeterminationDocument3 paginiMethod of Wage DeterminationPoonam SatapathyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Prepositions Underlining P 1 BeginnerDocument1 paginăPrepositions Underlining P 1 BeginnerRuth Job L. SalamancaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Chapter 3: Aims, Objectives and Policy ZonesDocument12 paginiChapter 3: Aims, Objectives and Policy ZonesShivalika SehgalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Baylor Law School 2013-2015 Academic CalendarDocument2 paginiBaylor Law School 2013-2015 Academic CalendarMark NicolasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grade 11 Ela Course OutlineDocument3 paginiGrade 11 Ela Course Outlineapi-246304404Încă nu există evaluări

- Sentence CorrectionDocument6 paginiSentence CorrectionDinesh RaghavendraÎncă nu există evaluări

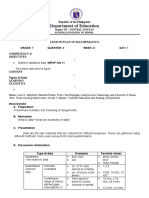

- Civic Movements.: Beyond Minimum KUD Beyond Minimum KUD Assessment TechniqueDocument14 paginiCivic Movements.: Beyond Minimum KUD Beyond Minimum KUD Assessment TechniqueJsyl Flor ReservaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Department of Education: Lesson Plan in MathematicsDocument2 paginiDepartment of Education: Lesson Plan in MathematicsShiera SaletreroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Frankland Tube Elect PDFDocument34 paginiFrankland Tube Elect PDFBill PerkinsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan in 21 Century LiteratureDocument2 paginiLesson Plan in 21 Century LiteratureClara ManriqueÎncă nu există evaluări

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)