Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Christmas

Încărcat de

pphreakkDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Christmas

Încărcat de

pphreakkDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

hristmas' Pagan Origins Few people realize that the origins of a form of Christmas was pagan & celebrate

d in Europe long before anyone there had heard of Jesus Christ. No one knows what day Jesus Christ was born on. From the biblical description, m ost historians believe that his birth probably occurred in September, approximat ely six months after Passover. One thing they agree on is that it is very unlike ly that Jesus was born in December, since the bible records shepherds tending th eir sheep in the fields on that night. This is quite unlikely to have happened d uring a cold Judean winter. So why do we celebrate Christ's birthday as Christma s, on December the 25th? The answer lies in the pagan origins of Christmas. In ancient Babylon, the feast of the Son of Isis (Goddess of Nature) was celebrated on December 25. Raucous p artying, gluttonous eating and drinking, and gift-giving were traditions of this feast. In Rome, the Winter Solstice was celebrated many years before the birth of Chris t. The Romans called their winter holiday Saturnalia, honoring Saturn, the God o f Agriculture. In January, they observed the Kalends of January, which represent ed the triumph of life over death. This whole season was called Dies Natalis Inv icti Solis, the Birthday of the Unconquered Sun. The festival season was marked by much merrymaking. It is in ancient Rome that the tradition of the Mummers was born. The Mummers were groups of costumed singers and dancers who traveled from house to house entertaining their neighbors. From this, the Christmas tradition of caroling was born. In northern Europe, many other traditions that we now consider part of Christian worship were begun long before the participants had ever heard of Christ. The p agans of northern Europe celebrated the their own winter solstice, known as Yule . Yule was symbolic of the pagan Sun God, Mithras, being born, and was observed on the shortest day of the year. As the Sun God grew and matured, the days becam e longer and warmer. It was customary to light a candle to encourage Mithras, an d the sun, to reappear next year. Huge Yule logs were burned in honor of the sun. The word Yule itself means "whee l," the wheel being a pagan symbol for the sun. Mistletoe was considered a sacre d plant, and the custom of kissing under the mistletoe began as a fertility ritu al. Hollyberries were thought to be a food of the gods. The tree is the one symbol that unites almost all the northern European winter s olstices. Live evergreen trees were often brought into homes during the harsh wi nters as a reminder to inhabitants that soon their crops would grow again. Everg reen boughs were sometimes carried as totems of good luck and were often present at weddings, representing fertility. The Druids used the tree as a religious sy mbol, holding their sacred ceremonies while surrounding and worshipping huge tre es. In 350, Pope Julius I declared that Christ's birth would be celebrated on Decemb er 25. There is little doubt that he was trying to make it as painless as possib le for pagan Romans (who remained a majority at that time) to convert to Christi anity. The new religion went down a bit easier, knowing that their feasts would not be taken away from them. Christmas (Christ-Mass) as we know it today, most historians agree, began in Ger many, though Catholics and Lutherans still disagree about which church celebrate d it first. The earliest record of an evergreen being decorated in a Christian c elebration was in 1521 in the Alsace region of Germany. A prominent Lutheran min ister of the day cried blasphemy: "Better that they should look to the true tree of life, Christ."

The controversy continues even today in some fundamentalist sects.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- God's Mind For The NT ChurchDocument14 paginiGod's Mind For The NT ChurchDavid A. DePraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Migne. Patrologiae Cursus Completus: Series Latina. 1800. Volume 20.Document612 paginiMigne. Patrologiae Cursus Completus: Series Latina. 1800. Volume 20.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gloria Jean Roddey Funeral ProgramDocument2 paginiGloria Jean Roddey Funeral ProgramHerb WalkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- St. Joseph Parish: 306 Iowa, PO Box 165, Olpe, KS 620-475-3326Document3 paginiSt. Joseph Parish: 306 Iowa, PO Box 165, Olpe, KS 620-475-3326Laurie SchmidtÎncă nu există evaluări

- CBCPMonitor Vol11-N12Document16 paginiCBCPMonitor Vol11-N12Areopagus Communications, Inc.Încă nu există evaluări

- 134th (2008) Acts & ProceedingsDocument629 pagini134th (2008) Acts & ProceedingsThe Presbyterian Church in CanadaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 30 Years War PPDocument11 pagini30 Years War PPapi-365135703100% (1)

- CIU Connection Spring 2010Document24 paginiCIU Connection Spring 2010Columbia International UniversityÎncă nu există evaluări

- Divine PraisesDocument2 paginiDivine PraisesChell MariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- January 9, 2011 BulletinDocument5 paginiJanuary 9, 2011 Bulletinpizpo625Încă nu există evaluări

- Cunningham. S. Augustin and His Place in The History of Christian Thought. 1886.Document340 paginiCunningham. S. Augustin and His Place in The History of Christian Thought. 1886.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sacerdotes Domini - ByrdDocument2 paginiSacerdotes Domini - ByrdWinston Bedia LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Augustine and Friends: Francis E Chambers, OSA April, 2012Document12 paginiAugustine and Friends: Francis E Chambers, OSA April, 2012321876Încă nu există evaluări

- CSI East Kerala Diocese, Brief Background By. Rev. Jacob Antony KoodathinkalDocument4 paginiCSI East Kerala Diocese, Brief Background By. Rev. Jacob Antony KoodathinkalRev. Jacob Antony koodathinkalÎncă nu există evaluări

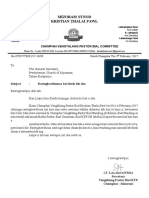

- Mizoram Synod Kristian - Halai Pawl: Presbyterian Church of IndiaDocument1 paginăMizoram Synod Kristian - Halai Pawl: Presbyterian Church of IndiabawihpuiapaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The 38 Most Ridiculous Things Martin Luther Ever Wrote - DavidLGray - InfoDocument34 paginiThe 38 Most Ridiculous Things Martin Luther Ever Wrote - DavidLGray - InfoAaron KingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bonhoeffer's Anti-Logos and Its Challenge To OppressionDocument14 paginiBonhoeffer's Anti-Logos and Its Challenge To Oppressionpsfranklin100% (1)

- Bison Courier, June 13, 2013Document20 paginiBison Courier, June 13, 2013surfnewmedia0% (1)

- Nine Day Novena in Honor of and Reparation To The Holy Face of JesusDocument5 paginiNine Day Novena in Honor of and Reparation To The Holy Face of JesusJESUS IS RETURNING DURING OUR GENERATIONÎncă nu există evaluări

- Birthday SongsDocument3 paginiBirthday SongsMarc Howell Babagay100% (1)

- CBCP Monitor Vol13-N8Document20 paginiCBCP Monitor Vol13-N8Areopagus Communications, Inc.Încă nu există evaluări

- 1.3 Storyboard Template 8 PanelsDocument1 pagină1.3 Storyboard Template 8 Panelsxoxogossipgirl777mÎncă nu există evaluări

- Resumen in Sik HongDocument8 paginiResumen in Sik HongEliud Miguel Madrid HuenupeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inerrant Adventist ThotDocument2 paginiInerrant Adventist Thotdaniel winters0% (1)

- Jellyfish Christianity: by J. C. RyleDocument2 paginiJellyfish Christianity: by J. C. RyleJohn GongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Appeal of The CultsDocument8 paginiAppeal of The CultsJesus LivesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutt Ziden Helen 1966 Rhodesia (Zimbabwe)Document14 paginiNutt Ziden Helen 1966 Rhodesia (Zimbabwe)the missions networkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apostles' Creed: Advanced InformationDocument11 paginiApostles' Creed: Advanced InformationmariceltriacabilingÎncă nu există evaluări

- 01 - Ensign - Jan PDFDocument84 pagini01 - Ensign - Jan PDFzesilva44100% (2)

- Booklet Microsoft Word 2Document44 paginiBooklet Microsoft Word 2Ludwig Santos-Mindo De Varona-LptÎncă nu există evaluări